ISSA Proceedings 2014 – Cultural Differences In Political Debate: Comparing Face Threats In U.S., Great Britain, And Egyptian Campaign Debates

Abstract: We compared recent historical debates from the U.S., Great Britain, and Egypt using politeness theory to determine if there were significant cultural differences and/or similarities in the way candidates argued for high office. The transcripts from these debates were coded using a schema based on face threats used in debates. Results indicate some differences between the way U.S. presidential candidates, British leaders, and Egyptian leaders initiate and manage face threats on leadership and competence.

Keywords: Campaign debates, culture, politeness.

1. Introduction

This paper explores cultural differences and similarities in argumentation strategies used by candidates in debates for high office. Recent historical campaign debates in Britain and Egypt offer an opportunity to examine cultural differences in reasoning about public affairs. Debates for the office of British Prime Minister were held for the first time in 2010 between Gordon Brown, David Cameron, and Nick Clegg. Similarly, Egypt held the first debate between Abdel Moneim Aboul Fotouh and Amr Moussa. To date, limited amount of work has been done on these historic events (see Benoit & Benoit-Bryan, 2013) and less is known about cultural differences in arguing for office.

Our interest is in the ways candidates manage face concerns in the potentially threatening encounters of campaign debates. These events are held in front of audiences who watch and deliberate over candidates’ political skills. Previous work has examined politeness strategies used by U.S. candidates for the presidency from 1960-2008 (Dailey, Hinck, & Hinck, 2008) and found a trend of declining reasoned exchanges over policy difference while direct attacks on character increased. Comparing the language strategies of the candidates representing different political cultures of the United States, Great Britain, and Egypt will allow us to explore trends in international campaign debate discourse.

2. The debates in context

On April 6, 2010 British Prime Minister Gordon Brown announced that dissolution of parliament and general election would take place in one month, May 6, 2010. At that time, power was relatively evenly divided between Gordon Brown’s Labour party and David Cameron’s Conservatives (Shirbon, 6 April 2010). The Liberal Democrats had a new leader in Nick Clegg. The campaign was significant in the sense that it was one of the few times that the politics of the time might result in a hung parliament, where three leading candidates running for office had not been the situation since 1979 (when Margaret Thatcher led the Conservatives, James Callaghan represented Labour, and David Steel was the candidate advanced by the Liberal party), where all three parties featured new leaders, and where debates were featured for the first time.

Three debates were held about one week apart in the one-month campaign. The first debate concerned domestic policy, the second international policy, and the third economic policy. Although a variety of issues were addressed under each of those subject areas, two main issues were of concern at the time (Shirbon, 6 April 2010). First, Britain was facing an economic crisis much like the U.S. was in the wake of the 2008 recession. Looming before the British government was a huge budget deficit and markets wanted a clear sense of direction regarding how the government would go about responding to the problem. Second, the outgoing parliament had been tarnished with an expenses scandal where one hundred and forty-five members of parliament were accused of inappropriate expenses while serving in office.

The format of the debate featured opening statements lasting one minute for each leader. After the three opening statements, the moderator would then take the first question on the agreed theme. Each leader was given one minute to respond to the question and then each leader had one minute to respond to the answers. The moderator was then allowed to open up the discussion for free debate for up to four minutes. Each leader was then given ninety seconds for a closing statement (BBC, 2010). According to the Select Committee on Communications’ Report (13 May 2014), the debates were a success: “the average viewing figures for each of the debates was 9.4 million (ITV), 4 million (Sky), and 8.1 million (BBC)” p. 12.

2.1 The 2012 Egyptian debate

The Moussa-Fotouh debate was the first and only political debate to have occurred in Egypt, at least at this point in time; thus, it was an important experiment in democratic practices for the Egyptian people in the immediate post-Mubarak political climate. The presidential debate between Amr Moussa and Abdel Moneim Abul Fotouh took place in Egypt May 10, 2012 and was sponsored by several media organizations. Moussa was the former foreign minister and former head of the Arab League, has also served as Ambassador of Egypt to the United Nations in New York, as Ambassador to India and to Switzerland. Abul Fotouh, is a medical doctor who was politically active since his college days. He was also a former member of the Muslim Brotherhood, an Islamic opposition party founded in 1928. The candidates had a very different relationship with the former regime under Hosni Mubarak. Moussa’s political career took place under Mubarak and Abul Fotouh was imprisoned for five years from 1996 to 2001. Despite the fact that these two candidates did not make the final election ballot, the selection of the candidates for that debate reflected the two leading candidates according to polls at that point in the campaign.

The Moussa-Fotouh debate structure was based on American presidential debates. Amr Khafaga, editor in chief of Al Shurouk newspaper, one of the sponsors of the debate said that, “there is no precedent for such an event in Egypt so they’ve borrowed the debate rules from the U.S. Egyptianizing it a bit” (The Guardian, 2012). The Christian Science Monitor reported that, “in the hour-long run-up, hosts explained that the format was based on US presidential debates, and broadcast part of the 1960 Nixon-Kennedy debate.” Mona el-Shazly, a talk show host and Yusri Fouda, a former Al-Jazeera journalist moderated the debate. The debate was divided into two parts consisting of 12 questions. The first half of the debate focused on the constitution and presidential powers and the second half focused on the candidates’ platforms, the judiciary and security. Each candidate was given two minutes to answer each question and was allowed to comment on the other’s responses. In addition, the candidates were permitted to ask each other one question at the end of each half of the debate. Each candidate had two minutes for closing remarks. We were unable to locate exact numbers for viewership but one estimate described viewership as reflecting a high rate of interest (Hope, 2012).

2.2 The 2012 U.S. presidential debates

President Barack Obama debated former Massachusetts Governor Mitt Romney three times during the 2012 presidential campaign. The record of the Obama administration’s first term included steering the country out of the greatest financial crisis since the Great Depression, sweeping new regulations of Wall Street, health care reform, ending American involvement in Iraq, beginning to draw down American forces in Afghanistan, and more (Glastris, 2012). Still, 52% of Americans polled during the 2012 campaign believed that the president had accomplished “not very much” or “little or nothing.” The economy was weak during the campaign and despite some promising news of job growth many Americans were open to the possibility of new leadership.

Mitt Romney had a successful record as a businessman and Governor. At Bain Capital he led the investment company to highly profitable ventures and then served as the CEO of the Salt Lake Organizing Committee for the 2002 Winter Olympics. In 2002 he was elected Governor of Massachusetts and passed health care reform at the state level. He campaigned vigorously for the Republican presidential nomination in 2008 but lost to John McCain. That campaign experience prepared him well for the 2012 campaign and in a long series of primary debates won the presidential nomination. During the primary campaign his communication strategy was to appeal to the base of the Republican party. In a leaked video of a private campaign speech Romney claimed that 47% of Americans pay no income taxes.

The fact that Bain Capital had made money by taking companies over to sell their assets with the result in some instances of eliminating jobs, that Romney had been opposed to bailing out the U.S. automobile industry while Obama had offered loans to save it, that Romney was opposed to health care reform on a national level when he had been in favor of it at the state level, and the 47% comment hurt Romney going into the last seven weeks of the campaign. According to Richard Wolffe (2013) “what had been a 4-to-5 point race in the battlegrounds became a 6-to-7 point race” (p. 204).

The debates provided Romney with an opportunity to change the dynamic of the campaign. Beth Myers (Myers & Dunn, 2013) who served as Romney’s Campaign Manager indicated there were three goals for the first debate: “create a credible vision for job creation and economic growth,” “present the case against Obama as a choice,” and “speak to women” (p. 101). Given the lead that Obama had developed in the battleground states, Obama’s advisers believed that he did not “need to be aggressive anymore because it’s kind of baked in there” (Wolffe, 2013, p. 210). However, Obama became “caught between what he wanted to say on stage and what his agreed strategy was. He couldn’t attack in case it destroyed his own popularity. But he needed to attack to show he had some backbone” (Wolffe, 2013, p. 213). The conflict resulted in a poor performance that energized the Romney camp. Viewership for the first debate was over 67 million (Voth, 2014), 65.6 million for the second debate (Stelter, 17 October 2012) and 59.2 million for the third debate (Stelter, 23 October 2012).

We compared the debates using Brown and Levinson’s politeness theory. This approach to the study of political debates has been described elsewhere (Dailey, Hinck, & Hinck, 2008; Hinck & Hinck, 2002). For the purposes of this study we examined the degree of direct threats on candidates’ positive face across the debates in order to answer the following research question.

RQ: Are there differences between face threat strategies in U.S., Great Britain, and Egyptian debates?

3. Method

3.1 Selection of debates and the acquisition of primary texts

Seven debates were coded and analyzed for this study. The texts of the three 2012 United States Presidential Debates featuring Governor Mitt Romney and President Barack Obama were found on the website of the Commission on Presidential Debates. The text of the three 2010 British Prime Minister Debates involving, Nick Clegg, David Cameron, and Gordon Brown were found on the BBC website (news.bbc.co.uk.). Finally, the text of the May 10, 2010 Egyptian Debate between Moussa and Abul Fotouh was created from a You Tube video of the event (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vrbkI1fkZFM&feature=player_embedded). An Egyptian native translated the debate transcript used for analysis from Arabic into English.

Unitizing the debates:

3.2 Unitizing and coding the debates

Two individuals served as coders of the transcripts. The coding process involved three decisions. First, the coders divided the transcripts into thought units. Hatfield and Weider-Hatfield (1978, p. 46) define a thought unit as “the minimum meaningful utterance having a beginning and end, typically operationalized as a simple sentence.” Since viewers of televised debates are interested in how candidates construct their messages unitizing the transcripts into statements of complete thoughts seemed most appropriate for this study.

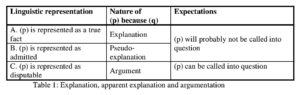

Second, the thought units were coded according to Dailey, Hinck, and Hinck’s (2008) coding schema. The coding schema is an extension of Kline’s (1984) social face coding system. Kline’s coding schema notes that positive politeness and autonomy granting/negative politeness are two separate dimensions of face support. Positive politeness is defined as the desire to be included and the want that one’s abilities will be respected. Negative politeness is defined as the want to be unimpeded by others. Positive face is supported by expressions of understanding solidarity, and/or positive evaluation; it is threatened by expressions of contradiction, noncooperation, disagreement, or disapproval. Since political debates are primarily concerned with a candidate’s ability to demonstrate his/her ability to lead, and to offer and explain policies and plans important to the well-being of the country, our analysis and coding schema focused on the positive face of the candidates. The coding schema is composed of three major levels. Statements at the first major level of the system are those that threaten the positive face of the candidates. Statements at this level of the system are further differentiated concerning the directness of the positive face attack (levels 1 and 2). Statements at the next major level of the system balance both threatening and supportive evaluative implications for the other’s face (level 3). Finally, statements at the final major level explicitly support the positive face of the candidates. Statements at this level of the coding system are further differentiated in terms of the directness of the positive support exhibited by the candidates (levels 4 and 5).

The third decision made by the coders focused on the topic of the action identified in the coded thought unit. Topics such as leadership/character, policy/plan, consequences of the plan, use of data, differences and/or disagreement between the candidates, campaign tactics, ridicule were identified.

3.3 Reliability

To determine intercoder reliability the two coders both coded the first quarter of the first 2012 Presidential debate, the first quarter of the first Prime Minister Debate, and the first quarter of the Egyptian debate. There was 92% agreement on the thought unit designation, and Cohen’s Kappa of inter rater agreement of .86 on the coding schema for the different content elements of the debate.

4. Results

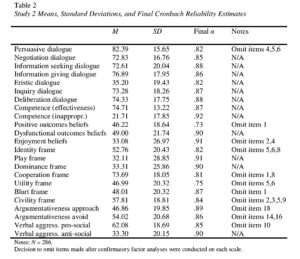

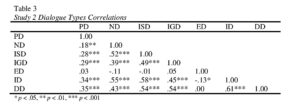

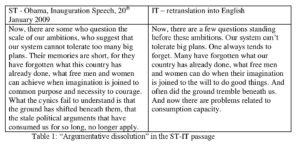

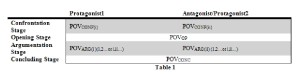

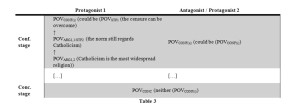

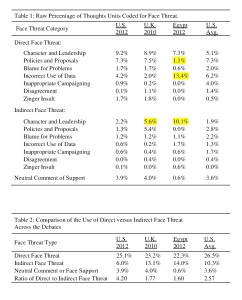

The sample for this particular study included seven debates (three U.S. Presidential debates in 2012, three Prime Minister debates in 2010, one Egyptian Presidential debate in 2012). Tables 1 through 4 contain the results of the coding of face threat in these debates according to the system we have developed and adapted over the last 12 years as was laid out in the Methods section.

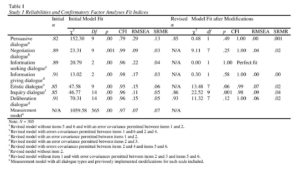

Table 1 has the raw percentage of thought units that were coded into one of the many categories of the coding scheme. For the U.S. and U.K. debates, these would be totals summed across the three debates. Also, included in all the tables are the averages for the coding categories for the debates from the 10 U.S. Presidential Campaigns we have coded before the 2012 debates.

Table 2 looks at combined categories of face threat according to directness of that threat. Over the program of research, we have found interesting information when we sum across the direct face threat and indirect face threat categories. This table also reveals a new way to look at the summed types by providing a ratio of the direct to indirect face threat. As a rough basis of comparison, in the 1960 U.S. Debates, this ratio was about 1.5, and in 2004 it was about 8.6. Generally, the preference for direct face attack has increased markedly across time, though the trend has been far from consistent. On the other hand, the decline in the use of indirect face threat has been fairly consistent starting at about 15% in 1960 and now hovering around 5% for the last three American campaigns.

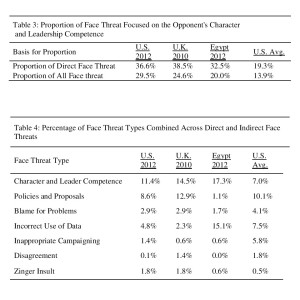

Table 3 presents what we consider a disturbing trend in modern debates. Among the categories of face threat, we regard the roughest as the personal attack on the opponent’s character and leadership competence. In essence, “nasty” debates would tend to have more of this personal attack on character and competence and less of a focus on plans, policies, and ideas. In 1960, around 3% of the face threat thought units were made up of this personal and direct attack on character and leadership competence. Even the proportion of direct face threat thought units spent on attacking the opponent’s character and leadership competence was only 4%. The highest proportions occurred in the 2012 debates, and those numbers are listed in Table 3. This is to say that more than a third of direct face threats in the debate were attacks on the opponent’s character and leadership competence.

Table 4 takes a look at the categories of face threat if we combine the direct and indirect face threat forms of those categories. Again, to place the values in some context across the U.S. Presidential debates, 2012 had the second highest percentage use of attacks of character and leadership competence and second lowest percentage of attacks on ideas, plans and policies.

The purpose of this particular study was mainly to uncover differences and similarities across the three cultures’ debates. We think it is useful to draw attention to five different outcomes we see from these recent debates. These are the use of direct face threat, the use of indirect threat, the use of attacks on character and leadership competence, use of attacks on plans, policies and proposals, and the use of attacks on the manipulation of data.

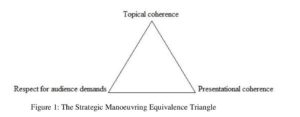

4.1 Direct face threat

A direct face threat is an attack on something about the opponent personally. For example, were Romney criticizing the Affordable Care Act, that would be an indirect face threat, but if he were criticizing “Obamacare,” then it would be a direct face threat as the plan is now personally linked to Barak Obama. What we see across the three sets of debates in this study is a remarkable consistency in the use of direct face threat, and percentages that mirror the U.S. average (see Table 2). This leads us to say that there appears to be a “natural” sort of direct face threat for these sorts of debates. The way that the different sets of debates arrived at this median value were very different and will be discussed below, but from a macro view, debates that vary, approximately 10% over this 25% value may be excessively rough, while debates that fall 10% below seem “quiet” and lack vigor.

4.2 Indirect face threat

In contrast to the overall level of direct face threat, the overall level of indirect face threat does vary across the three debate samples we use here. The U.S. debates show the very low level of indirect face threat that reflects a generally consistent decline across the American debates; both the British and the Egyptian debates show a high use of indirect face threat. Indeed, the British and Egyptian debate values for indirect face threat are just what would have been common in the early American debates, those that are held up as models for useful and healthy political discourse. Even in the ratio of direct to indirect face threat, the low values for the British and the Egyptians are on par with the low values from the early American debates. We view the American experience here as an indicator of the decline in the quality of debates, while the British and the Egyptians seem to have taken a better tact,.

4.3 Attacks on character and leadership competence

A disturbing trend in American political discourse is the vilification and demonization of opponents and enemies. This would include direct attacks centered on tearing down the nature, personality, abilities, and leadership of opponents. In American debates, up to 2000, the average percentage of direct attack on character and leadership competence was about 3.5%. After, 2000, the average percentage was 9.5%. Looking across the debates for this study, we see that higher level of direct attack on character and leadership competence in the British and Egyptian debates. When we look at the proportion of face threat expended in this type of personal attack, it is also quite high among each of our samples (see Table 3). Indeed, as noted above, the proportion of direct face threat focusing on direct attack on character and leadership competence in the 2012 American debates was the highest for any American debate, and the British exceeded even that number. Just as we are not encouraged by this trend in the American debates, we find it equally disturbing that the British and Egyptian debates also relied heavily on this rough form of campaign dialogue.

4.4 Attacks on ideas, positions, and plans

The proportion of thought units used to criticize the other’s plans and policies has remained fairly consistent over time for the American debates, more so in the case of direct attacks on the opponent’s plans and policies. In the results for this study (see Table 4), the Americans and the British debaters used about the same amount of direct attacks in this category as is the American average. The Egyptians, however, showed virtually no criticism or attack on the other’s plans and policies. Looking at the indirect attacks, such as criticism of a plan without also threatening the face of the opponent personally, the Americans show a small proportion of thought units, Egyptians show no thought units in the category, and the British show a very high level. Indeed, the American proportion is the lowest among the 11 American campaigns we have studied, while the British proportion is equal to the highest level among the American debates. In essence, the British candidates were behaving as the Americans did in the early days of televised debates. We think this form of attack in the debates, especially attacks and criticisms that don’t focus on a person as much as a plan, is one of the best practices for debates. Unfortunately, the Americans do not tend to use this form of debate behavior any more, and it appears in the case of this one Egyptian debate, there is also a lack of focus on plans and policies.

4.5 Attacks on use of data

Finally, one thing we found very striking about the comparisons here was the high percentage of thought units used to attack the opponent’s use of data in the Egyptian debate (see Tables 1 and 3). Basically this category includes those claims that the opponent (of the opponent’s administration or party) is using data in a biased and possible incorrect way. One may claim the other side isn’t revealing the whole picture of information that is available, that the other side was wrong in what it proposed was the other’s record on activities and statements, that the other side is not interpreting data as it should be, etc. We are used to seeing a prevalence of this type of argument or attack when the parties are claiming the other’s proposals and plans won’t work and are misguided. The attacked party might rebut saying the opponent’s criticism lacks merit due to a biased or incorrect interpretation of the data.

This was clearly not the case in the Egyptian debates. Even though the amount of attacks on data use far exceeded any American debate, the amount of attack on the opponent’s plans and policies was virtually nil. Upon examining the transcripts, we found the claims about inappropriate use of data were to rebut the opponent’s claims about one’s character and leadership. For example, if one party claimed (or implied as it turns out) that his opponent failed to resign from the Mubarak government after a certain incident, the other would claim that the accuser did not have the record of events correct or failed in his interpretation of the what actions the other did take. Indeed, the major portion of face threat in the Egyptian debate was about 1) the opponents’ character and leadership competence and then 2) the inappropriate way the would-be slanderer was using incorrect data in order to make the claim about deficient character or leadership.

5. Discussion

In looking at the aggregate results of direct and indirect face threats, the results indicating some similarities across the three campaigns. It was interesting to find that the amount of direct face threat across the sample mirrored the U.S. average of direct threat. This might be some indication of a cultural similarity. The fact that debates call for criticism of opposing candidates’ programs and records, and that the amount of direct face threat was similar in this sample suggests that more work might be done to assess standards of direct threat in other nations’ leader debates. However, these findings are limited to just the most recent campaigns and only one Egyptian debate. A larger, more comprehensive sample of debates from other countries might yield a different finding on the question of overall use of direct threats.

When we turn to a consideration of indirect face threat some interesting differences appear. The fact that U.S. indirect threats were low suggests a concern with U.S. presidential candidates reliance on direct attacks. We wonder whether the decreasing use of indirect attacks reflects a misguided assumption on the part of candidates and advisers that respect for the opponent’s face should be abandoned in the hope of generating an impression of a strong candidate. However, the fact the U.K. debates and the Egyptian debate showed higher levels of indirect face threat reveals a potential cultural difference between the state of U.S. debates and those of these other two countries.

Looking at specific content dimensions of the coding schema, the results concerning attacks on character and competence revealed a similarity between the three campaigns in terms of higher levels of direct face threats in the U.K. and Egyptians debates. However, it is interesting to note that with the U.K. this was a well established democracy while Egypt was attempting to model western democratic practices in their historic first experiment with a political debate. The uniqueness of the events might have accounted for the intense nature of attacks on character and competence. The debates in the U.K. took place in the context of three person race, a situation that had rarely occurred in the past. Egypt had never held debates before and the candidates had limited experience to draw on in preparing for the debates. Thus the high degree of direct attack on character and competence might have meant that the candidates and their advisers saw little value in balancing concerns for the face of the opponent with the need to advocate for office. This, however, does not explain the intensity of the U.S. debates. In the 2012 campaign, the direct attacks on character and competence were the highest for American debates since 1960. Also, however, the British debates exceeded even that number. We can only speculate that as the British campaign tightened up in the last few days, the candidates increased the intensity of their attacks in the hope of drawing distinctions between themselves in ways that might win over voters.

The last two findings raise some interesting topics regarding Egypt’s attempt to break free of authoritarian rule and move to a more democratic system of government. In terms of attacks on ideas, positions, and plans, American and British debates featured about the same amount of direct attacks, However, the Egyptian debate showed almost no instances where the candidates argued about ideas, positions, and plans. This finding by itself, suggests that the Egyptian candidates were less prepared to advance and test ideas, positions, and plans, and more predisposed to attack character and competence and to attack each other on the use of data. In fact, there was a high percentage of thought units devoted to attacking each person’s use of data in the Egyptian debate. When we looked more closely at the messages dealing with the use of data in the Egyptian debate, we realized that what we coded as arguments over the use of data could also be interpreted by an Egyptian as an attack on character or competence. For example, to say to your opponent that, “you must be using wrong information to come to such a conclusion as you have,” is considered to be an attack on a person’s capacity to see an issue in the same way that others do, that the opponent lacks the ability to make sense out of the social reality in the same way as most others do. Within this kind of a statement is an implied presumption for the candidate who utters such a comment and calls into question the opposing candidate’s ability to use

The last two findings raise some interesting topics regarding Egypt’s attempt to break free of authoritarian rule and move to a more democratic system of government. In terms of attacks on ideas, positions, and plans, American and British debates featured about the same amount of direct attacks, However, the Egyptian debate showed almost no instances where the candidates argued about ideas, positions, and plans. This finding by itself, suggests that the Egyptian candidates were less prepared to advance and test ideas, positions, and plans, and more predisposed to attack character and competence and to attack each other on the use of data. In fact, there was a high percentage of thought units devoted to attacking each person’s use of data in the Egyptian debate. When we looked more closely at the messages dealing with the use of data in the Egyptian debate, we realized that what we coded as arguments over the use of data could also be interpreted by an Egyptian as an attack on character or competence. For example, to say to your opponent that, “you must be using wrong information to come to such a conclusion as you have,” is considered to be an attack on a person’s capacity to see an issue in the same way that others do, that the opponent lacks the ability to make sense out of the social reality in the same way as most others do. Within this kind of a statement is an implied presumption for the candidate who utters such a comment and calls into question the opposing candidate’s ability to use  information in the same way that others do. Thus, it might be the case that to be sensitive to the different ways in which individuals from other cultures engage in argument over political issues in debates, some revision might be necessary to account for the differences in the way that communities engage in political argument.

information in the same way that others do. Thus, it might be the case that to be sensitive to the different ways in which individuals from other cultures engage in argument over political issues in debates, some revision might be necessary to account for the differences in the way that communities engage in political argument.

Last, we think that it is interesting that the Egyptian debate featured so few exchanges over ideas, positions, and plans. We think it might be the case that when a nation attempts to move away from authoritarian forms of rule, democratic traditions and practices need to be cultivated over longer periods and institutionalized as political traditions before they can achieve the promise of informing the electorate. Even after attempting to model the debate on the classic 1960 Kennedy-Nixon debates, the candidates did not engage in substantive exchanges over differences in ideas, positions, and plans. In conclusion, the results of the study indicate interesting differences between these debates and warrant further exploration of cultural differences in political debates.

6. Conclusion

To summarize our findings as we look across the intercultural sample of campaign debates, we found both similarities and differences. The similarities include the amount of direct face threat used, a level that has actually been fairly consistent across the American debates as well as the use of direct face threat used to attack the character and leadership competence of the opponent. The differences include the relatively low level of indirect face threat used by the Americans, the extremely low use of any criticism of plans and policies in the Egyptian debate as well as extremely high use of criticism of the manner in which an opponent has used or manipulated data.

References

Abramowitz, A. I. (1978). The impact of a presidential debate on voter rationality. American Journal of Political Science, 22, 680-690.

Baker, K. L., & Norpoth, H. (1981). Candidates on television: The 1972 electoral debates in West Germany. Public Opinion Quarterly, 45, 329-345.

Balz, D. (2013). Collision 2012: Obama vs. Romney and the future of elections in America. New York: Viking.

BBC (March 3, 2010). http://www.bbc.co.uk/blogs/theeditors/pm_debates_programme_format.pdf

Beck, C. S. (1996). “I’ve got some points I’d like to make here”: The achievement of social face through turn management during the 1992 vice presidential debate. Political Communication, 13, 165-180.

Benoit, W. L., & Benoit-Bryan, J. M. (2013). Debates come to the United Kingdom: A functional analysis of the 2010 British prime minister election debates. Communication Quarterly, 61, 463-478.

Benoit, W. L., & Henson, J. R. (2007). A functional analysis of the 2006 Canadian and Australian election debates. Argumentation and Advocacy, 44, 36-48.

Benoit, W. L., & Klyukovski, A. A. (2006). A functional analysis of 2004 Ukrainian presidential debates. Argumentation, 20, 209-225.

Benoit, W. L., & Sheafer, T. (2006). Functional theory and political discourse: Televised debates in Israel and the United States. Journalism and MassCommunication Quarterly, 83, 281-297.

Blais, A., & Boyer, M. M. (1996). Assessing the impact of televised debates: The case of the 1988 Canadian Election. British Journal of Political Science, 26, 143-164.

Blais, A., & Perrella, A. M. L (2008). Systemic effects of televised candidates’ debates. International Journal of Press/Politics, 13, 451-464.

Brown, P., & Levinson, S. C. (1987). Politeness: Some universals in language usage. Cambridge.

Carlin, D. P., & Bicak, P. J. (1993). Toward a theory of vice presidential debate purposes: An analysis of the 1992 vice presidential debate. Argumentation and Advocacy, 30, 119-130.

Chaffee, S. H. (1978). Presidential debates—are they helpful to voters? Communication Monographs, 45, 330-346.

Coleman, S. (Ed.). (2000). Televised election debates: International perspectives. New York: St. Martin’s.

Cmeciu, C., & Patrut, M. (2010). A functional approach to the 2009 Romanian presidential debates. Case Study: Crin Antonescu versus Traian Basescu. Journal of Media Research, 6, 31-41.

Dailey, W. O., Hinck, E. A., & Hinck, S. S. (2008). Politeness in presidential debates: Shaping political face in campaign debates from 1960-2004. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Deans, J. (16 April 2010). Leaders’ debate TV ratings: 9.4m viewers make clash day’s biggest show. The Guardian. http://www.theguardian.com/media/2010/apr/16/leaders-debate-tv-ratings

Dudek, P., & Partacz, S. (2009). Functional theory of political discourse. Televised debates during the parliamentary campaign in 2007 in Poland. Central European Journal of Communication, 2, 367-379.

Egyptian presidential election TV debate-as it happened. (2012, May 10). The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/middle-east-live/2012/may/10/egypt-presidential-election-debate?newsfeed=true

Fitzgerald, G. (23 April 2010). http://news.sky.com/story/774618/tv-debate-clegg-and-cameron-neck-and-neck

Galasinski, D. (1998). Strategies of talking to each other: Rule breaking in Polish presidential debates. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 17, 165-182.

Geer, J. (1988). The effects of presidential debates on the electorate’s preferences for candidates. American Politics Quarterly, 16, 486-501.

Glastris, P. (March/April, 2012). The incomplete greatness of Barack Obama. Washington Monthly. http://www.washingtonmonthly.com/magazine/march_april_2012/features/the_incomplete_greatness_of_ba035754.php

Goffman, E. (1967). Interaction ritual: Essays on face to face behavior. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

Hatfield, J. D., & Weider-Hatfield, D. (1978). The comparative utility of three types of behavioral units for interaction analysis. Communication Monographs, 45, 44-50.

Hinck, E. A. (1993). Enacting the presidency: Political argument, presidential debates and presidential character. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Hinck, E. A., & Hinck, S. S. (2002). Politeness strategies in the 1992 vice presidential and presidential debates. Argumentation and Advocacy, 38, 234-250.

Hinck, E. A., Hinck, S. S., & Dailey, W. O. (2013). Direct attacks in the 2008 presidential debates. In Clarke Rountree (Ed.), Venomous speech: Problems with American political discourse on the right and left. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

Hinck, S. S., Hinck, R. S., Dailey, W. O., & Hinck, E. A. (2013). Thou shalt not speak ill of any fellow Republicans? Politeness theory in the 2012 Republican primary debates. Argumentation and Advocacy, 49, 259-274.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations (2nd Ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hope, B. (May 11, 2012). First presidential debate reveals a wide open race. The national. http://bradleyahope.com/2012/05/11/first-presidential-debate- reveals-wide-open-race/

House of Lords. (13 May 2014). Select committee on communications. 2nd Report of Session 2013-2014: Broadcast general election debates. http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201314/ldselect/ldcomuni/171/171.pdf

Jalilifar, A., & Alavi-Nia, M. (2012). We are surprised; wasn’t Iran disgraced there? A functional analysis of hedges and boosters in televised Iranian and American presidential debates. Discourse and Communication, 6, 135-161.

Jamieson, K. H., & Adasiewicz, C. (2000). What can voters learn from election debates? In S. Coleman (Ed.), Televised debates: International perspectives (pp. 25-42). New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Jamieson, K. H., & Birdsell, D. S. (1988). Presidential debates: The challenge of creating an informed electorate. New York: Oxford University Press.

Katz, E., & Feldman, J. J. (1977). The debates in light of research: A survey of surveys. In S. Kraus (Ed.), The great debates: Kennedy vs. Nixon, 1960 (pp. 173-223). Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Khang, H. (2008). A cross-cultural perspective on videostyles of presidential debates in the US and Korea. Asian Journal of Communication, 18, 47-63.

Kline, S. (1984). Social cognitive determinants of face support in persuasive messages. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Illinois at Champaign, Urbana.

Lanoue, D. J. (1991). Debates that mattered: Voters’ reaction to the 1984 Canadian leadership debates. Canadian Journal of Political Science, 24, 51-65.

LeDuc, L., & Price, R. (1985). Great debates: The televised leadership debates of 1979. Canadian Journal of Political Science, 18, 135-153.

Maier, J., & Faas, T. (2003). The affected German voter: Televised debates, follow-up communication and candidate evaluations. Communications, 28, 383-404.

McKinney, M. S., & Warner, B. R. (2013). Do presidential debates matter? Examining a decade of campaign debate effects. Argumentation and Advocacy, 49, 238-258.

Myers, B., & Dunn, A. (2013). Debate strategy and effects. In K. H. Jamieson (Ed.) Electing the president 2012: The insider’s view (pp.96-121). Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania.

Nagel, F., Maurer, M., & Reinemann, C. (2012). Is there a visual dominance in political communication? How verbal, visual, and vocal communication shape viewers’ impressions of political candidates. Journal of Communication, 62, 833-850.

Reinemann, C., & Maurer, M. (2005). Unifying or polarizing? Short term effects and postdebate consequences of different rhetorical strategies in televised debates. Journal of Communication, 55, 775-794.

Rowland, R. C. (2013). The first 2012 presidential campaign debate: The decline of reason in presidential debates. Communication Studies, 64, 528-547.

Schroeder, A. (2008). Presidential debates: Fifty years of high risk TV (2nd ed.). New York: Columbia University Press.

Shirbon, E. (6 April 2010). British parties launch month-long election campaign Reuters. http://www.reuters.com/article/2010/04/06/us-britain-election- idUSTRE63512T20100406

Stelter, B. (17 October 2012). The New York Times. http://mediadecoder.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/10/17/2nd-debate-also-a- ratings-hit-drawing-65-6-million-athomeviewers/?php=true&_type=blogs&module=Search&mabReward=relbias%3Ar&_r=0

Stelter, B. (23 October 2012). The New York Times.

http://mediadecoder.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/10/23/final-debate-draws- nearly-60-million viewers/?module=Search&mabReward=relbias%3Ar

Voth, B. (2014). Presidential debates 2012. In R. E. Denton, Jr. (Ed.), The 2012 presidential campaign: A communication perspective (pp. 45-56). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Wolffe, R. (2013). The message: The reselling of President Obama. New York: Twelve.