1. Introduction: the concept of legal fiction [i]

1. Introduction: the concept of legal fiction [i]

In eighteenth-century England, as we can see from a notorious story reproduced in different contemporary pieces of writing in the philosophy and history of law (Perelman 1999, p. 63; Perelman 1974, p. 348; Friedman 1995, p. 4, part II), the provisions of the criminal law insisted on the death penalty for every culprit accused of “grand larceny”. According to the same law, “grand larceny” was defined as the theft of anything worth at least two pounds (or 40 shillings). Nevertheless, in order to spare the lives of the defendants, the English judges established a regular practice which lasted for many years, to estimate every theft, regardless of its real value, as though it were worth 39 shillings. The culmination of that practice was the case when the court estimated the theft of 10 pounds, i.e. 200 shillings, as being worth only 39 shillings, and thus revealed an obvious distortion of the factual aspect of that, as well as of many previous cases.

The said situation and the corresponding judicial solution of it represent one of the most utilized classical examples of the phenomenon of what is called “legal fiction” (or more adequately in this case, “jurisprudential fiction”). This concept designates a specific legal technique based on the qualification of facts which is contrary to the reality, that is, which supposes a fact or a situation different from what it really is, in order to produce a certain legal effect (Perelman 1999, p. 62; Salmon 1974, p. 114; Foriers 1974, p. 16; Delgado-Ocando 1974, p. 78, 82; Rivero 1974, p. 102; de Lamberterie 2003, p. 5; see also Smith 2007, p. 1437, Moglen 1998, p. 3, part 2 A).

However, this definition is not free from internal difficulties. Namely, the use of the terms “facts” and “reality” in its formulation immediately triggers the controversy between the common-sense, unreflective concept of factual reality as something that is simply “out there”, waiting to be checked and identified, and the more sophisticated concept of “facts” and “reality” appropriate for the legal context. Namely, the latter takes into account the constructive capacity of institutional norms and rules to produce complex forms of legally relevant realities (“theft”, “murder”, “marriage”, “contract”, “association”, etc.), consisting of a specific mixture of “brute” and “institutional” factual elements (Searle 1999, pp. 122–134).

That is why some authors insist on the point that in order to be counted as proper legal fictions, it is not enough that the fictional legal statements simply involve an element of counterfactuality opposed to the common-sense reality; they must, moreover, be contrary to the existing legal reality. Thus, for instance, Perelman claims that if the existent legal reality is established by the legislator, like in the case of associations and other groups of individuals that are treated as legal personalities, then we are not entitled to consider it legal fiction, although it deviates from the psychological, physiological and moral reality in which the persons are identified as individual human beings. However, if, Perelman argues, a judge grants the right to sue a group of individuals that does not represent a legal personality, while the right to sue is reserved only for groups constituted as legal personalities, he is in fact resorting to the use of legal fiction (Perelman 1999, pp. 62-63). A similar position is also advocated by Delgado-Ocando, who subscribes to Dekker’s view that legal fiction should not be considered a violation of “natural facts”, but, essentially, a deliberately inaccurate use of the actual legal categories (Delgado-Ocando 1974, p. 82). Thus, using the above-mentioned definition of legal fictions as “a qualification of facts contrary to reality”, I will bear in mind this specific meaning of “contrary-to-legal-reality”, because I see as convincing the view that the existing legal reality, which includes the factual components but is not reducible to them, is the real target of the fictional reconfiguration by means of this peculiar legal technique.

Within this conceptual framework, the main goal of my approach to the issue of legal fictions will be twofold. First, through the analysis of some practical examples of legal fictions taken from different national jurisprudences, I will attempt to isolate the general argumentative mechanism of legal fictions by using some of the fundamental ideas and insights developed in different branches of the contemporary argumentation theory. Second, given the possible abuse of legal fictions as an instrument of legal justification, the emphasis will be placed on the issue concerning the possibility for the formulation of certain criteria in establishing the difference between the legitimate and the illegitimate use of this argumentative technique. However, in order to do this it will be necessary, first, to define the distinction between legal fictions and another kind of legal phenomena with which they are sometimes confused – legal presumptions, and second, to distinguish the different kinds of legal fictions that exist. Those distinctions will enable us to focus our attention solely on those aspects of the complex issue of legal fictions which are relevant for the purpose of this paper.

2. Legal fictions vs. legal presumptions

On a theoretical level, the question concerning the relation of legal fictions to legal presumptions is still a controversial one. The reason for this is most probably the fact that both legal fictions and legal presumptions establish a sophisticated relationship to the element of factual truth involved in a legal case in the sense that they both treat as true (in a legally relevant sense) something which is not, or may not be true in a factual sense. Thus, the presumption may be defined as an affirmation which the legal officials consider to be true in the absence of proof of the contrary, or even, in some cases, notwithstanding the proof of the contrary (cf. Goltzberg 2010, p. 98: “Affirmation, d’origine légale ou non, que le magistrat tient pour vraie jusqu’à preuve du contraire ou même dans certains cas nonobstant la preuve du contraire”). For example, a child born to a husband and wife living together is presumed to be the natural child of the husband; an accused person is presumed innocent until found guilty; an act of the state administration is presumed to be legal, etc., although in some cases those presumptions may be shown not to correspond to the factual state of affairs.

When discussing the issue of the relationship of legal fictions and legal presumptions, it is necessary to mention the classical dichotomy of presumptions into presumptions juris tantum and presumptions juris et de jure, i.e., “simple”, rebuttable presumptions, which admit proof of the contrary, and “absolute”, irrefutable presumptions, which do not admit proof of the contrary. For instance, the presumption of the paternity of the legitimate husband is rebuttable because it can be proven that the husband is not the real biological father of the child born within the marital union; on the other hand, the presumption that everyone knows the law (“no one is supposed to ignore the law”, or in the well-known Latin formulation, “nemo censetur ignorare legem”) is usually treated as an example of an irrefutable presumption because it is not possible to avoid liability for violating the law in criminal or in civil lawsuits merely by claiming ignorance of its content.

This distinction is significant in the issue of legal fictions because they are sometimes assimilated into the category of irrefutable presumptions. Thus, for instance, Wróblewski argues that irrefutable presumptions are the source of legal fictions because they cannot be discarded and because they formulate assertions which cannot be demonstrated to be false by reference to reality (Wróblewski 1974, p. 67: “Particulièrement la source des fictions se trouve dans les présomptions irréfragables, praesumptiones iuris et de iure, car elles ne peuvent être écartées, elles formulent donc des assertions dont la fausseté n’est pas démontrable par une référence à la réalité”).

However, the reasons for accepting this view do not seem to be conclusive. First, irrefutable presumptions and legal fictions establish different relations to the element of factual truth involved in a legal dispute. Namely, the irrefutable presumption just makes it irrelevant, in the sense that this kind of presumption does not allow the claims of the factual truth contrary to the presumed truth to be even taken into consideration in deciding the case. On the other hand, the legal fiction starts with the identification of the factual reality in the case at hand, but then distorts the standard qualification of facts that would be appropriate for this case in order to include them in another legal category and to produce the desired legal effect. Second, it seems reasonable to claim, as Foriers does, that legal presumptions and legal fictions belong, in fact, to different segments of legal theory and practice: the presumptions are related to the theory (and practice) of legal proof, regulating the possible objects of proof and the distribution of burden of proof between the parties, while legal fictions are related to the theory (and practice) of the extension of legal norms, or of their creating and legitimatizing (Foriers 1974, p. 8). That is why in the present approach, adopting the view of a fundamentally different nature of legal presumptions and legal fictions, my interest will be restricted only to the latter, without underestimating, of course, the genuine interest that legal presumptions legitimately raise as an object of study of contemporary research in legal argumentation.

3. Kinds of legal fictions

Legal fictions, as an interesting technical device, the use of which represents a pervasive trait of the legal practice from Roman times to the present, are not a homogenous class. The kinds of legal fictions vary depending on the segment of the legal system in which they are created and utilized. Thus, according to the criterion of their origin, we can distinguish legislative, doctrinal and adjudicative (jurisprudential) fictions (Delgado-Ocando 1974, p. 92; Foriers 1974, p. 16).

Legislative fictions, being those established by the legislator himself, can be further sub-divided into the categories of “terminological” and “normative” fictions. In the case of terminological fictions, the legislator fictionally qualifies a factual situation which is obviously contrary to the common-sense conceptual reality, like in the case when the law stipulates that some physically movable objects – animals, seeds, utensils, etc. – are to be considered immovable goods (Article 524 of the French and Belgian Civil code). Normative legislative fiction, on the other hand, is that which adds a complementary norm to the terminological stipulation, because without invoking that norm it would be impossible for the fiction to play out its role. An example of this situation may be found in Article 587 of the French and Belgian Civil code, in which the legislator regulates the rights and duties of the usufructuary (a person who has the right to enjoy the products of property they do not own). Namely, the right to usufruct usually presupposes the conservation of the object (i.e. not damaging the property) that is being used. However, in order to further extend the right to usufruct also to things that cannot be used without being consumed, like money, grains, liquors, etc., the legislator is obliged to include a supplementary norm that, following the completion of the usufruct, the usufructuary should replace the consumed objects with such of similar quantity, quality and value. Thus, in this case, the fictional assimilation of expendable goods in the category of legitimate objects of usufruct is made possible by the introduction of a “meta-rule” that should justify or counterbalance the violation of the fundamental nature of the institution of usufruct (Foriers 1974, pp. 19-20).

Although the distinction between legislative and doctrinal legal fictions is not always easy to establish, it may be said that doctrinal fictions are theoretical devices whose function is to pave the road for the reception of new legal categories or to justify the implicit ideological basis of the legal system. Thus, the theories of the “declarative function of the judge” (judges are not entitled to create or to interpret the law, that being the function of the legislator) and of the “inexistent gaps in the law” (the system of law is complete and capable of regulating every legal dispute) are treated as examples of “doctrinal fictions”, which attempt to assure the theoretical and systematic stability of the actual legal order (Delgado-Ocando 1974, p. 99).

However, for the purpose of this paper, the most important and the most interesting for argumentative analysis are the fictions of the third, adjudicative kind (usually called “jurisprudential fictions”, especially in the French-speaking tradition). These are the fictions used in judicial reasoning as strategic instruments in attaining the desired aim by a deliberately inaccurate use of the existent legal categories and techniques of legal qualification. The specificity of jurisprudential fictions lies in their dynamic and unpredictable nature, in the sense that they are created “ad hoc” in the function of the resolution of a particular, usually difficult and complex legal case. As Perelman points out, their use is particularly frequent in criminal law, when the members of the jury or the judges strive to avoid the application of the law that they find unjust in the circumstances of the specific case. This is the case not only in the classical “39-shillings” example, but also in the twentieth-century French and Belgian legal practices, when in several cases involving euthanasia the jury did not find the defendants guilty of the death of the deceased, although in the corresponding national legislatives there was no established distinction between euthanasia and simple murder (Perelman 1999, p. 63).

Nevertheless, jurisprudential fictions are not restricted solely to criminal cases; they may also be used in other legal areas, such as constitutional, civil, administrative, international law, etc. One particularly illustrative example can be taken from a former Yugoslavian and, subsequently, Macedonian legal practice from the area of contract law in the late 1960s. Namely, the existent law on the sale of land and buildings recognized legal validity only to those agreements concluded in written form, explicitly denying it to the non-written ones. However, in deciding the practical cases in which the sources of the dispute were orally concluded agreements, and in order to prevent manipulations with their consequences (for instance, the attempts of their annulment following the completion of the transfer of the property and money), the court decided to assimilate oral agreements into the category of written agreements and to accord them the same legal status, provided that they had been carried out (decision of the supreme Court of Yugoslavia R. no. 1677/65 from 18.03.1966; cited from Чавдар 2001, p. 155).

Although jurisprudential fictions are usually generated in order to deal with perplexing practical cases, they may also function as a source in creating new legislative rules (as was actually the case with the “39-shillings decision”, or with the decision of the Yugoslavian Supreme Court to treat oral agreements, under certain conditions, as if they were written ones, which were later incorporated in the law in the form of general rules). This is, amongst others, one of the important reasons which make the phenomenon of jurisprudential fictions worthy of theoretical and practical attention and which will be further commented on in the concluding section of this paper.

4. Jurisprudential fictions and their argumentative role

Regardless of the definition of legal fictions that we are ready to adopt, it is obvious that the strong counterfactual element necessarily involved in fictions which are used in judicial reasoning and motivation of judicial decisions makes their nature extremely controversial. Namely, it obviously collides with one of the fundamental demands of legal procedures – the need to establish the factual truth which lies in the basis of a lawsuit and to stick to it in the determination of the outcome of the legal dispute. Even if we agree that the concept of truth does not have the same meaning in the courtroom, in a scientific or philosophical investigation, or in everyday use, it cannot be denied that the mechanism of jurisprudential fictions is based on the deliberate refusal to adhere, for legal purposes, to the established truth of the facts in the case (for instance, the truth that the value of the theft is more than 39 shillings, or that the defendant voluntarily caused the death of another human being, or that the contract was not concluded in writing, etc.).

On the other hand, it is a well-known fact that the demand for the adherence to the truth in the adjudicative context cannot be easily disregarded because it arises primarily from the need to assure objectivity, impartiality and legal certainty in the administration of justice. Consequently, every aberration from it spontaneously raises suspicions that the respect of those fundamental values may be somehow placed in danger. This is perhaps the main reason why, in the history of legal thought, especially in the common law tradition in which the use of legal fictions in the process of adjudication was especially frequent, they were often perceived in a negative light, as a technique of manipulation by the judges, which corrupted the normal functioning of the legal system. The most prominent representative of that stance is Jeremy Bentham, in whose opinion legal fictions were simply usurpations of legislative power by the judges. He even compares the fiction to a nasty disease, syphilis, which infects the legal system with the principle of rottenness (cf. Smith 2007, p. 1466; Klerman 2009, p. 2; Fuller 1967, p. 2-3). Furthermore, in a contemporary context, there are also opinions which label legal fictions as dangerous and unnatural technical means in the law (cf. Stanković, 1999, p. 346).

However, there is also another side to this, which, being more sympathetic to the phenomenon of legal (or, in this context, jurisprudential) fictions, treats them as an important, useful and generally legitimate legal technique. In this perspective, they are viewed, essentially, as instruments that help their authors to determine and justify the correct outcome of a legal dispute, to obtain a result which would be compliant to equity, justice or social efficiency (Perelman; cf. de Lamberterie, 2003, p. 5), especially in difficult and perplexing legal situations, when the established legal rules cease to “encompass neatly the social life they are intended to regulate” (Fuller 1967, p. viii). Thus, legal fictions are sometimes described as “white lies” of the law (Ihering; cf. Fuller 1967, p. 5), lies “not intended to deceive” and not actually deceiving anyone (Fuller 1967, p. 6), lies which are also “benefactors of law” (Cornu; cf. de Lamberterie 2003, p. 5) because they serve as a means to protect the important values of the legal and social world which may sometimes be endangered precisely by the very mechanical application of the existing legal rules.

As it is obvious even from this simplified description, the phenomenon of legal fictions mobilizes a corpus of very deep questions concerning the relations of law, reality and truth, the hierarchisation of legal values, the distribution of power between the legislative and the adjudicative officials within the framework of the legal system, the legitimate and illegitimate use of judicial discretion, etc. However, in my present approach, I shall focus only on those elements of the phenomenon of legal, or, more precisely, of jurisprudential fictions which are relevant for the analysis of legal reasoning from the point of view of the argumentation theory. Namely, it seems to me that the unveiling of the complex mechanisms of reasoning which those fictions use in applying the norms to the distorted factual reality is of crucial significance for the better understanding also of the other aspects of their functioning within the socio-legal context.

As a theoretical platform for analyzing the phenomenon of jurisprudential fictions, I would suggest a combination of two general ideas developed in the different orientations of the contemporary argumentation theory: first, the idea of legal justification as the essence of legal argumentation, and second, the idea of strategic maneuvering as an indispensable instrument of legal technique, especially in what is called “difficult cases”. Allow me to briefly comment on each of the above-mentioned.

4.1. Jurisprudential fictions as justificatory devices

The importance of justificatory techniques in legal, and especially in judicial reasoning, is nicely summarized in the formulation that the acceptability of a legal decision is dependent on the quality of its justification (Feteris 1999, p. 1). However, some theoreticians of legal argumentation, as for example, Robert Blanché, are prepared to go even further and to affirm that judicial argumentation is, in its essence, justification. Namely, according to this view, behind the façade of an impartial derivation of legal conclusions from the normative and the factual premises, in the judicial reasoning there is always an effort to justify a certain axiologically impregnated legal standpoint (Blanché 1973, pp. 228–238).

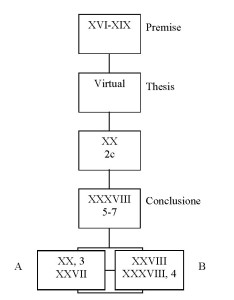

The main point of this insistence to the justificatory nature of legal argumentation is the need to emphasize the fundamentally regressive character of legal reasoning. The qualification “regressive” in this context means that in this type of reasoning the starting points are not the principles from which we progressively derive the consequence, but rather the consequence itself, from which we regress to the principles from which it may be derived (Blanché 1973, p. 12). Thus, in the context of legal reasoning, whilst the deliberation is treated as a progressive procedure in which the judge is seeking a solution for a legal problem, starting from a complex of legal principles, the justification is essentially a regressive procedure, which begins from the decision, that is, from the solution of the problem, and seeks the reasons and arguments which can support it (Blanché 1973, pp. 228-230).

It seems that the existence and the functioning of jurisprudential fictions strongly support the thesis of a fundamentally regressive character of legal argumentation. Namely, the need to use a fiction in the motivation of a judicial decision emerges only when it is necessary to find a way to justify a legal conclusion which, for some reason, does not fit in the existing legal framework, but which has already been estimated by the judge as the most satisfactory solution to the legal issue at hand. However, legal fictions are a type of non-standard justificatory device because they demand a deeper, riskier and more artificial argumentative maneuver than a search for reasons and arguments, which can simply be extracted from the existing regulation. In fact, the very need for fictional justification of a legal decision is a symptom of the disputable status of its legitimacy in the current legal framework, or an indicator that in the previous process of judicial deliberation which led to that decision, the boundaries of the system, for better or worse, have already been transgressed (for the difference in the justificatory function of “classical” and “new” legal fictions, see Smith 2003).

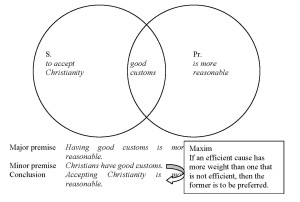

From the above-mentioned examples it is clear that the need to use jurisprudential fictions arises in situations when no exception to the rule, no alternative interpretation and no ambiguous rule can be invoked by the judge in order to evade the unacceptable result of the application of the relevant legal norm and to justify the desired legal outcome of the case (for instance, sparing the life of a petty thief, granting the legally relevant status of orally concluded, yet realized agreements, etc.). Thus, not being entitled to assume, not openly at least, a legislative role and to change the legal rule which generates the undesired conclusion, the author of the jurisprudential fiction resorts to the modification of the other element on which the syllogistic structure of their reasoning is based – the factual premise.

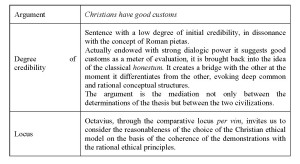

From an argumentative point of view, the false qualification of facts, their deliberate assimilation in a legal category to which they obviously do not belong, represents a procedure which combines the techniques of reasoning a contrario and a simili in an idiosyncratic and rather radical argumentative maneuver (for the use of arguments a contrario as a technique of justification of judicial decisions, see Canale & Tuzet 2008, and Jansen 2008). Namely, the use of fiction is based on the identification not of similarity, but precisely of the essential difference between the categories to which the technique of assimilation is applied (“grand” and “small” larceny, “oral” and “written agreement”, etc.). In fact, the fiction is in demanding an analogical treatment of two legally relevant acts in spite of the explicit recognition of their inequality (Delgado-Ocando, 1974, p. 82).

This analogical treatment of obviously different legal facts, which amounts to the assimilation of some of them in a category other than that they would normally belong to, is the key move which makes it possible for the judge to use the logical force of the subsumptive pattern of legal reasoning in order to justify his/her decision. For instance, if the rule of law provides that only written agreements are legally valid, and the oral agreement which is the object of the dispute is fictionally assimilated into the category of written agreements, it follows that it is also legally valid and should be protected by the law. To wit, the new, modified factual premise is now suitable for generating the desired conclusion under the general and unchanged normative premise.[ii]

4.2. Jurisprudential fictions as instruments of strategic maneuvering

The treatment of judicial fictions as specific justificatory instruments of “last resort”, by which the judge attempts to fulfill his/her strategic role – that of legitimatizing a decision which cannot, stricto sensu, be justified by the standard means in the existing legal framework – is very close to the conceptual horizon opened up by the theory of “strategic maneuvering” applied in a legal context (van Eemeren & Houtlosser 2005; Feteris 2009).

Legal, and especially judicial argumentation, like any other kind of argumentation, represents a goal-directed and rule-governed activity, with a strongly manifested agonistic aspect. However, one of the peculiarities of judicial argumentation is the fact that the justification and the refutation of legally relevant stances, opinions and decisions is realized within a strictly defined institutional framework, bounded by many restrictions not only of a logical, but also of a legal, substantial, as well as a procedural nature. Moreover, because of the conflicts of values, conceptions and interests in the social context, the judicial decisions are usually the object of numerous controversies and should be capable of withstanding sharp criticism in a dialogically structured (potential or actual) argumentative exchange. That is the reason why the argumentative strategies and instruments used in legal justification, especially in difficult cases, are complex and multi-layered; to wit, they have to represent an optimal plan to justify a particular decision taken as the most adequate and fair solution of the case at hand, in accordance with the strict demands of the legal system, and to defend it against any possible argumentative attack.

The concept of the argumentative maneuver in a legal context comes into play in those challenging situations when the judicial conviction of the fairness and rightness of a particular decision conflicts with the relevant norms applicable to the specific case. In that kind of situation, the judge operates in the (usually, fairly limited) space left for his/her “margin of appreciation”, trying to find argumentative means to fulfill the strategic goal of justification by using the instruments which are placed at his/her disposal by the legal system.

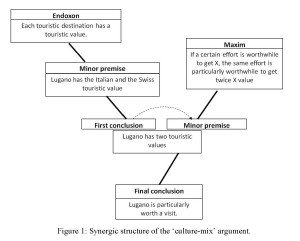

In general, the techniques of interpretation of legal rules (linguistic, genetic, systematic, historical, etc.), which enable to broaden or to restrict their scope by invoking the intention of the legislator, the origin and the evolution of the rule, the nuances of meaning of terms in its formulation, etc., are used as tools in this strategic maneuvering (on this point, besides the above-mentioned Feteris 2009, it could be instructive to see also van Rees 2009 and Ieţcu-Fairclough 2009). Viewed, generally, as an “attempt to reconcile dialectical obligations and rhetorical ambitions” (van Eemeren & Houtlosser 2005, p.1), the strategic maneuvering in the justification of judicial decisions is an indispensable instrument in resolving the tension “between the requirement of legal certainty and the requirement of reasonableness and fairness” (Feteris 2009, p. 95).

This general function of strategic maneuvers used in legal justification is the main reason for suggesting that the phenomenon of legal fictions could also be treated as a specific type of such maneuvering, although comprised in a broader sense than the interpretative maneuvers stricto sensu, capable of being adequately accounted for by the pragma-dialectical analytical apparatus (like, for instance, in Feteris 2009). Namely, in the above-mentioned examples of the judicial use of fictions, the refusal to apply (at least, in a straightforward way) the general legal norm to the established facts of the case was inspired by the need to meet the standard of reasonableness and fairness of the decision, while the move of falsely qualifying the facts was intended to integrate the judicial solution into the structure of paradigmatic legal reasoning, as one of the warrants of legal certainty. Nevertheless, the specificity of legal fictions compared to other forms of strategic maneuvering in the legal area lies in the fact that the target of this maneuver is not the rule itself and its possible interpretations, but the very facts of the case which make it possible (or impossible) to subsume it under that particular legal rule. However, this move reveals, simultaneously, the inherently controversial connotations of the notions “maneuver” and “maneuvering”, which may sometimes also denote an implicit attempt to undermine or to subvert the legitimate functioning of legal rules, while creating only the impression that they are being consistently observed.

In that way, the use of fictions as strategic means in legal reasoning and argumentation shares the crucial question treated in the contemporary theory of strategic maneuvering in argumentation: how to establish the difference between the legitimate and the illegitimate use of this technique, between its “sound” and its “derailed” instances (van Eemeren & Houtlosser 2009)? Namely, when it is affirmed that the use of fiction aims to produce a desired legal outcome, the adjective “desired” is burdened by a particularly dangerous form of ambiguity. The effect desired by a corrupted or biased judge, to bear in mind the Benthamian warnings, may be, for example, the protection of particular political, economic or personal interests, the discreditation or elimination of political adversaries, the legitimatizing of an oppressive politics by a (nationally or internationally) dominant class or ideology, etc. Obviously, the fictional distortion of existent reality in order to bring about legal consequences is a pricey move, a move which may serve the search for justice and equity equally well as it may hinder it.

The problem of the criteria in distinguishing the legitimate and the illegitimate use of legal fiction as a technique of justification of judicial decisions, especially in difficult legal cases in which “the legal reasoning falters and reaches out clumsily for help” (Fuller 1967, p. viii), is too complex and too difficult to be resolved by a simple theoretical gesture. On this occasion, I would venture only to make two suggestions in the direction of making preparations for its more elaborate treatment in the future.

First, it seems that the criteria of sound and derailed argumentative use of fictions are not an absolutely homogenous class, but that they could be differentiated according to the legal area to which the case with fictional justification belongs: civil, criminal, constitutional, etc. The reason for this is the fact that in different legal areas there are different articulations of the fundamental legal relationships between the concerned subject and agents, different standards of acceptable methods of proof and justification. For instance, as it is well known, the use of analogical reasoning in criminal law is not allowed, whilst in civil law the norms governing its use are more permissible. Thus, a detailed identification of the existent standards of use of argumentative techniques in each legal area could represent a useful clue to the elaboration of criteria of the acceptable application of the fictional legal devices in it.

Second, if we feel that notwithstanding the differences in the area of application, there should be a more general formulation of the criterion of the legitimate use of legal, or, more precisely, jurisprudential fictions, perhaps we should explore the direction open by the formulations of the “principle of universalizability” (cf., for instance, Hare 1963) suitable for the legal context – like, for example, Perelman’s “rule of justice” (Perelman & Olbrechs-Tyteca 1983, p. 294), or Alexy’s “rules of justification” in the rational practical discourse (Alexy 1989, pp. 202-204). Namely, in all of these examples the underlying idea is that one of the fundamental features of fair application of legal rules is its capacity for universalisation, in the sense that the treatment accorded to one individual in a given legally-relevant situation, should also be accorded to any other individual who is in a similar situation in all relevant aspects. Applied to the problem of jurisprudential fictions, it would mean that if the judge is prepared, in an ideal speech situation, to openly declare the normative choice obfuscated by the fictional means and to plead for its universalisation to the status of precedent for other cases or of a general rule that should be explicitly incorporated in the legal system, then it can be treated as a positive sign (although not as an absolute or clear-cut criterion) of the legitimacy of its previous use. Supposedly, the protection of partial political, economic or ideological interests “covered” by the derailed uses of fictions in judicial reasoning should not be able to pass the hypothetical or the actual test of universalizability.

In fact, in a historical sense, the universalisation, i.e. the extension of a particular judicial solution to other similar cases, was the general effect of the use of some famous legal fictions, including those from our examples, which contributed to the sensibilisation of legal and social authorities to the existing gap between the reality and the norms, and to the overcoming of it by creating new legal rules. In that way, legal fictions, in spite of their controversial nature, or perhaps just because of it, are shown to be, not only in history, but also in the present, a powerful impetus of the conceptual and normative evolution, in the legal, as well as in the philosophical and logical sense of the word.

5. Conclusion

In this paper, an attempt was made to approach the issue of legal and, especially, jurisprudential fictions by using the theoretical and conceptual tools developed within the framework of the contemporary argumentation theory. Two ideas were discussed as particularly suitable in the realization of this goal: the idea of legal justification as a fundamental aspect of legal argumentation and the idea of strategic maneuvering as an indispensable tool of the technique of justification of legal decisions, especially in “difficult” legal cases. From this perspective, legal fictions used in judicial reasoning have been treated as peculiar, non-standard justificatory devices and instruments of strategic maneuvering. Their main function is related to the attempt to reconcile the desirability of a certain judicial solution seen as the most reasonable and fair decision in the case at hand, with the demands of the existing legal order, especially the demands of legal certainty. Given the possibility of the abuse of fictions as an instrument in legitimatizing the inappropriate usurpation of normative power by judges, particular attention was accorded to the issue of the criteria of their legitimate and illegitimate use, and the potential of universalization of a particular legal fiction was suggested as a possible indicator of the appropriateness of being resorted to in judicial reasoning.

NOTES

i The author wishes to thank the editors and the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on a previous version of this paper.

ii An interesting question, which deserves a more elaborate treatment and more detailed research, is the question if the reasoning mechanisms involved in the creation and utilization of legal fictions can be plausibly accounted for from the point of view of the contemporary theories of defeasible reasoning in law (on the problem of defeasibility in judicial opinion cf. Godden & Walton 2008).

REFERENCES

Alexy, R. (1989). A Theory of Legal Argumentation – The Theory of Rational Discourse as Theory of Legal Justification. (R. Adler & N. MacCormick, Trans.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. (Original work published 1983). [English translation of Theorie der juristischen Argumentation. Die Theorie des rationalen Diskurses als Theorie der juristischen Begründung].

Blanché, R. (1973). Le raisonnement. Paris: PUF.

Canale, D., & Tuzet, G. (2008). On the contrary: Inferential analysis and ontological assumptions of the a contrario argument. Informal Logic, 28(1), 31-43.

Retrieved from http://ojs.uwindsor.ca/ojs/leddy/index.php/informal_logic/article/view/512/475

Code civil français. Retrieved from http://perlpot.net/cod/civil.pdf

Code civil belge. Retrieved from http://www.droitbelge.be/codes.asp#civ

Delgado-Ocando, J. M. (1974). La fiction juridique dans le code civil vénézuélien avec quelques références à la législation comparée. In Ch. Perelman & P. Foriers (Eds.), Les présomptions et les fictions en droit (pp. 72-100). Bruxelles: Émile Brylant.

Eemeren, F. H. van (Ed.). (2009). Examining Argumentation in Context: Fifteen Studies on Strategic Maneuvering. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Eemeren, F. H. van, & Houtlosser, P. (2005). Strategic maneuvering. SComS: Argumentation in Dialogic Interaction, 23-34.

Eemeren, F. H. van, & Houtlosser, P. (2009). Strategic maneuvering: Examining argumentation in context. In F. H. van Eemeren (Ed.), Examining Argumentation

in Context: Fifteen Studies on Strategic Maneuvering (pp. 1-24). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Feteris, E. T. (1999). Fundamentals of Legal Argumentation – A Survey of Theories on the Justification of Judicial Decisions. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Feteris, E.T. (2009). Strategic maneuvering in the justification of judicial decisions. In F. H. van Eemeren (Ed.), Examining Argumentation in Context: Fifteen Studies on Strategic Maneuvering (pp. 93-114). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Foriers, P. (1974). Présomptions et fictions. In Ch. Perelman & P. Foriers (Eds.), Les présomptions et les fictions en droit (pp. 7-26). Bruxelles: Émile Brylant.

Friedman, D. (1995). Making sense of English law enforcement in the 18th century. The University of Chicago Law School Roundtable. Retrieved from http://www.daviddfriedman.com/Academic/England_18thc./England_18thc.html

Fuller, L. L. (1967). Legal Fictions. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Godden, D.M., & Walton, D. (2008). Defeasibility in judicial opinion: Logical or procedural? Informal Logic, 28(1), 6-19. Retrieved from http://ojs.uwindsor.ca/ojs/leddy/index.php/informal_logic/article/view/510/473

Goltzberg, S. (2010). Présomption et théorie bidimensionnelle de l’argumentation.Dissensus 2010/3, 88-99. Retrieved from popups.ulg.ac.be/dissensus/docannexe.php?id=666

Hare, R.M. (1963). Freedom and Reason. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ieţcu-Fairclough, I. (2009). Legitimation and strategic maneuvering in the political field. In F. H. van Eemeren (Ed.), Examining Argumentation in Context: Fifteen Studies on Strategic Maneuvering (pp. 131-151). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Jansen, H. (2008). In view of an express regulation: Considering the scope and soundness of a contrario reasoning. Informal Logic, 28(1), 44-59. Retrieved from http://ojs.uwindsor.ca/ojs/leddy/index.php/informal_logic/article/view/513/476

Klerman, D. (2009). Legal fictions as strategic instruments. Law and Economics

Workshop, Berkeley Program in Law and Economics, UC Berkeley (pp. 1-18). Retrieved from http://www.escholarship.org/uc/item/8zv9k24m

Lamberterie, I. de. (2003). Préconstitution des preuves, présomptions et fictions. Sécurité juridique et sécurité technique: indépendance ou métissage. Conférence organisée par le Programme international de coopération scientifique (CRDP /CECOJI), Montréal, 30 Septembre 2003. Retrieved from www.lex-electronica.org/docs/articles_106.pdf

Moglen, E. (1998). Legal fictions and common law legal theory: Some historical reflections. Retrieved from http://emoglen.law.columbia.edu/publications/fict.html

Perelman, Ch. (1974). Présomptions et fictions en droit, essai de synthèse. In Ch. Perelman & P. Foriers (Eds.), Les présomptions et les fictions en droit (pp. 339-348). Bruxelles: Émile Brylant.

Perelman, Ch. (1999). Logique juridique: Nouvelle rhétorique. (2e éd.). Paris: Dalloz.

Perelman, Ch., & Foriers, P. (Eds.). (1974). Les présomptions et les fictions en droit. Bruxelles: Émile Brylant.

Perelman, Ch., & Olbrechts – Tyteca, L. (1983). Traité de l’argumentation: La nouvelle rhétorique. (4e éd.). Bruxelles: Éditions de l’Université de Bruxelles.

Rees, M.A. van. (2009). Strategic maneuvering with dissociation. In F. H. van Eemeren (Ed.), Examining Argumentation in Context: Fifteen Studies on Strategic Maneuvering (pp. 25-39). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Rivero, J. (1974). Fictions et présomptions en droit public français. In Ch. Perelman & P.

Foriers (Eds.), Les présomptions et les fictions en droit (pp. 101-113). Bruxelles: Émile Brylant.

Salmon, J. J. A. (1974). Le procédé de la fiction en droit international. In Ch. Perelman &

P. Foriers (Eds.), Les présomptions et les fictions en droit (pp. 114-143). Bruxelles: Émile Brylant.

Searle, J. (1999). Mind, Language and Society: Doing Philosophy in the Real World. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Smith, P. J. (2007). New legal fictions. Retrieved from http://www.georgetownlawjournal.com/issues/pdf/95-5/SMITH.pdf

Stanković, G. (1999). Fictions on the statement of the appeal in the legal procedure. Facta Universitatis, 1(3), 343-356.

Wróblewski, J. (1974). Structure et fonction des présomptions juridiques. In Ch. Perelman & P. Foriers (Eds.), Les présomptions et les fictions en droit (pp. 43-71). Bruxelles: Émile Brylant.

Чавдар, К. (2001). Закон за облигационите односи: коментари, објаснувања,

практика и предметен регистар. (Law of obligations: commentaries, explications, practice and index) Скопје: Академик.

1. Introduction

1. Introduction