ISSA Proceedings 2010 – Image, Evidence, Argument

1. Introduction

1. Introduction

Suppose that visual argument skeptics are correct: there are no visual arguments apart from any associated verbal content. Does it follow, then, that there is no place for images in argumentation theory or informal logic? The answer to this question, I argue, is no – at least in the case of photographic images. Instead, photographic images can fill an evidentiary role in which the image acts as a verifier, corroborator or refuter of some claim within an argument. This result is satisfying in two ways. First, it makes room for images even under the most hostile conceptions of argument for visual argumentation. Second, it forms the basis of an answer to a related question in philosophy of mathematics. In philosophy of mathematics, there is a debate about the role of diagrams in mathematical reasoning. This debate, in some respects, mimics the debate about the use of visual elements in argumentation. I show that the use of images as verifiers in argumentative contexts can inform an answer about the use of some diagrams in mathematical contexts. Diagrams can verify, corroborate or refute claims in mathematical arguments. Hence, though this doesn’t mean that diagrams are proofs, it means that diagrams can play an evidentiary role in mathematical contexts.

As a preamble to this discussion, I describe and label several positions one can take as regards visual evidence. On one end of the spectrum one finds the proponent of visual arguments. This is the position of Leo Groarke (Groarke 1996, Groarke 2002) and David Birdsell (Birdsell and Groarke, 1996, Birdsell and Groarke 2007). The proponent takes visual arguments to be no less legitimately arguments than any verbal arguments. For example, Groarke offers a poster from the University of Amsterdam as a putative visual argument (Groarke 1996, p. 112). Regarding the argumentative status of the poster, Groarke is unequivocal. He writes, “From the point of view of logic, the poster is something more than a statement, for it visually makes the point that the University of Amsterdam’s chief adminstrators are all men, to back the intended claim that the university needs more women.” (Groarke 1996, p. 111) A proponent of visual argument, then, takes the resources needed to analyze visual arguments to include logic broadly construed. Groarke doesn’t limit the analysis and evaluation of visual argumentation to just the rhetorical powers of images; though he doesn’t neglect these either. Instead, the proponent as I envision him or her, thinks that argumentation includes visual elements in the most robust forms possible. Therefore, Argumentation Theory and Informal Logic ought to expand to account for these visual elements explicitly.

Before describing some middle ground in this spectrum, I consider the other end: the visual argument skeptics. The skeptic denies the possibility or actuality of visual arguments. David Fleming (Fleming 1996) and Ralph Johnson (Johnson 2003) are examples of visual argument skeptics. The skeptic needn’t deny the rhetorical power of images, but the skeptic does deny that the images are arguments properly so called. Johnson, for example, thinks that many of the items claimed by proponents to be visual arguments will, under scrutiny, turn out not to be arguments at all or will not be essentially visual insofar as the argumentative workload will be handled by associated verbal elements (Johnson 2003, pp.10-11). Both Johnson and Fleming offer accounts of argument that may by fiat rule out visual arguments. “An argument is a type of discourse or text – the distillate of the practice of argumentation – in which the arguer seeks to persuade the Other(s) of the truth of a thesis by producing reasons that support it. In addition to this illative core, an argument possesses a dialectical tier in which the arguer discharges his dialectical obligations.” (Johnson 2000, p. 168) “To sum up, argument is reasoning towards a debatable conclusion. It is a human act conducted in two parts (claim and support) and with awareness of two sides (the claim allows for and even invites opposition).” (Fleming 1996, p. 18) Thus, Fleming argues that there is no way, on his conception of argument, for visual arguments to be anything more than “support for a linguistic claim.” (Fleming 1996, p. 19) But these visual elements are not arguments.

Between these extremes there are a variety of positions that one might take. One position is that of Anthony Blair (Blair 2004). Blair’s position as regards visual arguments seems to be reductionist, and hence, I would place it closer to the skeptic than the proponent. The logical content of visual arguments is propositional; hence, the logical analysis of visual arguments requires finding the associated verbal content of the putative visual argument. The rhetorical elements of visual arguments are, for Blair, not reducible to the verbal content (Blair 2004, p. 59). However, these elements pertain not to logic, i.e., to logical support, but to (mere) persuasive communication. The appraisal of visual arguments, then, reduces to two tasks. First, one must identify and interpret the associated verbal content. Second, one must determine the rhetorical strength of the visual appeal. This appraisal of visual arguments, then, does not determine the logical strength of any of the inferences, or if it does, this appraisal will fail to capture the unique rhetorical influences of the visual elements.

There are surely other positions between skeptics and proponents. Yet, for present purposes, this classification is sufficient. The skeptics deny that visual arguments are arguments proper, while the proponents accept that visual arguments are simply arguments. Between these two views, one might take visual arguments to be visual attempts at persuasion without allowing visual arguments to have subtle logical forms. But what is important for my purpose is that on the skeptical side of the spectrum, the objections to visual arguments are that they are either wholly rhetorical or, if there is any logical content, it is overly simple and identifiable with some associated verbal content. I want to take this claim – that visual arguments are either wholly rhetorical or have logical content identified with or reducible to associated verbal content – seriously without also thereby marginalizing visual argumentation.

To be clear, I am not attempting to show that visual arguments are arguments in the strictest sense. Instead, I think there is a place for the consideration of the visual within argument appraisal even granting the skeptics main premises. So, what are the skeptic’s worries? Fleming worries that unadorned images lack the necessary properties of arguments (Fleming 1995, p. 15). A picture can function as evidence, but as such is not thereby a component of an argument. Instead, the image is outside of the argument. To be a part of the argument, for Fleming, the image must be capable of asserting some claim. And, apparently, evidence isn’t assertion.

It is tempting to take Fleming’s criticism of visual arguments as resting on an untoward distinction: pure versus mixed visual arguments. Let a pure visual argument be a putative argument that contains only visual elements essentially, i.e., it completely lacks verbal elements. A mixed visual argument, then, would be one that contains both visual and verbal elements essentially. Fleming’s criticism, then, would apply only to pure visual arguments. However, it is unclear what sense to give to “essentially” in this construction. One might take it to mean that an argument is essentially visual if and only if some visual element contains no associated verbal content. Taken this way, visual arguments are probably ruled out by fiat. This suggests that a better interpretation of visual arguments regards the mode of presentation. An argument is visual if it presents some element of an argument visually. In this way, the distinction is dissolved. It isn’t as if the proponents of visual argument are attempting to make it the case that the appraisal of visual arguments concerns ineffable and wholly visual content devoid of associated verbal elements. Instead, the proponents think that there are reasons to take the interpretation of visual elements as a yet under researched mode of argumentation. It is worth noting that all of the purported examples of visual argument given by Groarke contain verbal elements explicitly. Indeed, taken in this way, Fleming’s criticism is straw. None of the proponents seem to take images as sufficient for arguments. Instead, images are components of arguments.

Still, Fleming’s complaint is that images don’t bear the right kind of relationships to verbal entities to be considered even a part of arguments. And this is where one can start to make room for the visual. Fleming himself goes part of the way in this regard. “So, if the visual cannot function as both claim and support (unless we make the distinction between them meaningless), and if it cannot, without language, be a claim, we are left with only one possibility: the visual can serve as support for a linguistic claim.” (Fleming 1996, p. 19) He goes on to focus on the rhetorical aspects of images. But for present purposes, we are left with the following: why isn’t the claim that the visual can serve as support for a linguistic claim enough to make room for the visual in argumentation. I think that it is. To see this, I next consider a scientific use of photographs.

2. Visual Evidence in Science

The last scientifically accepted sighting of an Ivory Billed Woodpecker (IBWO) occurred in Louisiana in 1944 by Don Eckelberry. Since then, there have been numerous unsubstantiated sightings, including several apparent photographs. Sadly, by most accounts, the IBWO has become extinct. Thus it was a great surprise to read the title of a paper in Science, “Ivory Billed Woodpecker (campephilus principalis) Persists in Continental North America,” (Fitzpatrick, et al 2005, p. 1460). In the article, the claim that the IBWO persists was (mostly) supported by the analysis of a short, blurry video. Since visual evidence plays such an important role in this scientific argument, it makes a good case study for the use of visual elements in (some) scientific arguments.

The IBWO is a very large woodpecker up to 20 inches long with a wingspan of up to 31 inches. Its appearance is similar to another woodpecker that has not suffered the same fate. A pileated woodpecker (PIWO) can be up to 18 inches long with a wingspan of up to 25 inches. Both species are mostly black with various white and, in the case of males of both species, red plumage. The differences, though slight, are important. The trailing feathers on the wings of the IBWO are white while these feathers are black on a PIWO. The back of an IBWO has a white segment, while the back of a PIWO is black, etc.

The background for the argument is explained by the authors of this paper thusly. “At 15:42 Central Daylight Time on 25 April 2004, M. D. Luneau secured a brief but crucial video of a very large woodpecker perched on the trunk of a water tupelo (Nyssa aquatica), then fleeing from the approaching canoe. The woodpecker remains in the video frame for a total of 4 [seconds] as it flies rapidly away. Even at its closest point, the woodpecker occupies only a small fraction of the video. Its images are blurred and pixilated owing to rapid motion, slow shutter speed, video interlacing artifacts, and the bird’s distance beyond the video camera’s focal plane. Despite these imperfections, crucial field marks are evidence both on the original and on deinterlaced and magnified video fields. At least five diagnostic features allow us to identify the subject as an ivory-billed woodpecker.” (Fitspatrick et al. 2005, p. 1460) Aside from the technical term, “deinterlaced,” the setup is straightforward. A video frame is typically composed of two separate images that are interlaced to make up the image that we view. This interlacing can be problematic when someone wants to view a single frame of video tape. The two images are taken at fractionally different times and can therefore introduce unnecessary noise into the image. These frames can be deinterlaced by software. The deinterlaced image will be clearer than its interlaced counterpart. We are in a position, now, to analyze this argument. In its roughest form, the argument accumulates evidence in favor of the sub-conclusion that the subject of the video is an IBWO. From there we have, perhaps, an argument from sign (cf. Walton 2008, p.10) for the main conclusion that the IBWO persists.

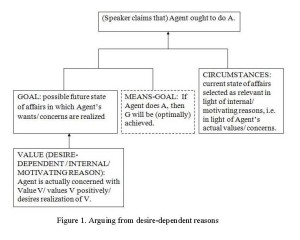

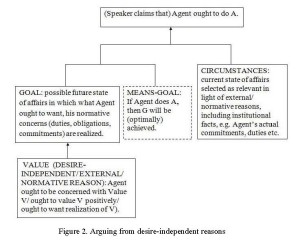

The accumulation argument contains, at the very least, the five diagnostic features visible in the video. These include: the size of the bird, the ratio of white to black feathers at rest, the color of the feathers on the trailing edge of the bird as it flies away, the pattern of white feathers on the dorsum (back) of the bird as it flies away, and the pattern of white feathers on the bird as it is perched on a tree. Here are two possible reconstructions of this argument using the following numbered premises and conclusion. I give two reconstruction because I don’t want to take a stand as to the proper reconstruction of an accumulation argument (i.e., whether the premises are independent or linked in some less-than-logical sense). (1) The bird on the video is too large to be a PIWO but the right size to be an IBWO. (2) The ratio of white to black feathers on the wings of the bird at rest are inconsistent with a PIWO but consistent with an IBWO. (3) The pattern of feathers on the back of the bird as it flies are inconsistent with an PIWO but consistent with an IBWO. (4) The color of the feathers on the trailing edge of the bird’s wings are inconsistent with a PIWO but consistent with an IBWO. (5) The pattern of white feathers on the back of the perched bird are inconsistent with a PIWO but consistent with an IBWO. Hence, (C), if the bird on the video is a woodpecker, then it is an IBWO rather than a PIWO. (See Figures 1 and 2)

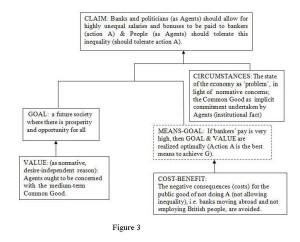

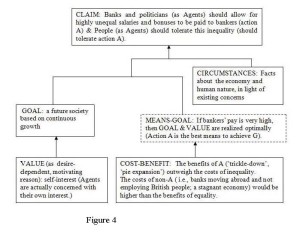

It is important to note that as reconstructed, the images don’t (seem to) play any role whatsoever in the argument. However, to evaluate the argument requires examining the video images. To take just one example: how do we know whether the argument from (3) to (C) is legitimate? There are at two levels of appraisal here. First, there is the evaluation of the support that (3) if true provides for (C). Second, there is the evaluation of the truth, acceptability or plausibility of (3). The image works in this second place. That is, if you want to know whether it is true that the pattern of black and white feathers on the back of the bird as it flies are inconsistent with a PIWO but consistent with an IBWO you have to look at the image. The image may verify or refute this claim, supposing it is clear enough to distinguish the relevant features. The other premises are also verified, refuted or corroborated, to the extent that they can be, by the associated images. I think Fleming is correct that this connection is something different from assertion. It would, perhaps, be a mistake to reconstruct the argument from (3) to (C) along the following lines (see Figure 3).

There are many issues for such a reconstruction. For example, how do we evaluate the strength of the inference from the image to (3)? Moreover, this reconstruction invites a bit more detail. The image in this reconstruction is probably operating within the context of a more subtle argument regarding the patterns of feathers on the two types of woodpeckers. Hence, one would expect there to be more detail about the patterns of feathers. Supposing that such a reconstruction were possible, it would likely be covered by some general scheme, say, argument from photographic evidence. Then, like an argument from sign (Walton 2008, p.10), we would expect a canonical form as well as a series of critical questions that allow for a standard appraisal of this argument form. Still, I don’t see how the picture would fit into the argument any better than with a simple exhortation, “see!” At which point the arguer invites the recipient of the argument to see for himself or herself the visual evidence. Hence, it is probably better keep the evidential relation separate.

This account of visual evidence does not carry over to all so-called visual arguments. For example, it is clear that editorial cartoons don’t appeal to visual elements as verifiers of claims. So, this result is limited to cases of visual evidence such as photos, videos and x-rays.

3. Visual Evidence in Legal Settings

Though not every visual element can be thought of as a verifier or refuter, we can see that this account of visual evidence as verification/refutation makes sense outside of science. In law, for example, photographs are regularly used as evidence. In an odd legal case from California (People v. Doggett, 1948), a couple was convicted of a crime. This isn’t by itself unusual. What is unusual is that the only evidence offered at the trial was a photograph. “In that case a husband and wife were convicted of a violation of section 288a of the California Penal Code, which makes criminal all acts of oral sexual perversion. The only evidence introduced at the trial to support a conviction was a photograph of the husband and wife in the commission of the alleged act. Supporting witnesses testified only as to the probable authenticity of the photographs without having perceived the commission of the alleged act.” (Mouser and Philbin 1957, p. 311) There are two things to question about this use of photographs. First, what property of photographs allow them to work as evidence? Second, what are the limitations for such uses? Regarding the first question, it is clear that photographs offer a visual representation of some objects. Moreover, although photos can be better or worse regarding focus, depth of field and the like, the representation is thought to be more or less accurate regarding the things represented, their spatial relations etc. Thus, by examining a photo one is presumed to have perceived some of the properties and relations of the things represented in the photo. As a more mundane example, consider the National Football League’s use of instant replay as a check on the calls of the referees. When a team challenges a call, the referee checks the instant replay. In cases where the referee has “indisputable visual evidence” to overturn the call, the referee changes the call. If videotape systematically distorted the properties and relations of the objects on the videotape to such a degree that the referee could not perceive the apparent properties and relations, there would be no reason to use videotape as a check. For the purposes of reviewing calls, videotape represents the properties and relations of the objects with enough accuracy to aid the referee in reviewing calls.

Something like this must be happening with photos (and videotape) in courtrooms as well. If photos were continually distorting the properties and relations of the objects represented, then the perception of the objects would not be accurate. And if the perception weren’t accurate, the use of photos would be deemed unreliable as a method for establishing facts in court. In the case of the Doggetts, the photo was apparently sufficiently compelling to warrant conviction.

Before moving on to the limits of the use of photos in court cases, I want to reconsider the actual use of photos to establish, verify or corroborate facts. One might be tempted to think that in the case of the Doggetts, there was a rather straightforward warrant for conclusion: the photo clearly showed the Doggetts engaged in an illicit act; hence, they were engaged in that act. The supporting witnesses didn’t testify regarding the act, but only to the authenticity of the photo. So, it was the photo, along with the authentication that led to the conviction.

The problem with this account, though, is that we can’t reconstruct the case as a traditional argument. That is, in reconstructing the prosecution’s case, the photo verifies the claim that the Doggetts engaged in the illicit act without also being a premise for that claim. Here’s a possible reconstruction of the argument. (1) If the Doggetts engaged in the illicit act, then they should be convicted. (2) The Doggetts engaged in the illicit act. So, (3) the Doggetts should be convicted. The logic of the case is modus ponens. Yet, there is no room for the photo in the logic of the argument. But, we must not think that the only distinction is between logic and rhetoric here. In this case, the rhetorical force of the photo is unimportant. Instead, what matters is whether premise (2) is true. The photo doesn’t support the claim logically, as logical support is about the flow of truth values or truth-like values from a reason or set of reasons to a conclusion. Instead, the photo merely verifies truth without offering logical support. One doesn’t infer the truth of the claim from the photo, one perceives it. I don’t want to enter a discussion of the theory-ladenness of perception. Instead, I distinguish the process of inferring, in which a claim garners support conditionally upon the acceptance of some other claims, from the process of perception, whereby one apprehends the truth or falsity of a claim by visual comparison. The statement verified is different from the configuration of objects that constitute the subject of the statement.

The use of a photo in legal settings always has an associated verbal argument. Moreover, the photo’s role in the argument will be as claimed above: corroboration, verification or refutation. The strength of this evidence will depend on many factors: clarity of the photo, for example. But it is the argumentation that gets logical criticism. The photo gets a different type of criticism altogether.

4. Visual Mathematical Evidence

Turning now to mathematical examples, there are many mathematical results that are justified by non-deductive means. James Franklin (Franklin 1987) gives a litany of non-deductive methods. But, diagrammatic reasoning isn’t one of them. The reason, I think, is that Franklin is interested in logical rather than evidential methods – even when the logic is non-deductive or probabilistic. I don’t think there is a general logic for figurative reasoning, though there is much interesting logical work on certain diagrammatic systems. Some of this work derives from Ken Manders’s (Manders 2008) account of Euclidean Diagrams. I don’t want to discourage this kind of research. Yet, I am unconvinced that every case of figurative reasoning will be, much less should be, formalized. Instead, I want to consider a different possibility. Figurative proofs or arguments are associated with (perhaps tacit) verbal arguments. In such cases, the figurative elements operate much in the same way as photographs do in the law and in science: the figures verify, corroborate or refute specific claims. The claims, as verbal elements, are used in the actual reasoning. But the figurative elements are visual evidence for the associated claims rather than stand-alone arguments or proofs. Consider Figure 4 below.

This is supposed to be a proof of the claim 1 + 3 + 5 + … + (2n – 1) = n2. The argument that it leads to the conclusion is this. (1) 1 = 12. (2) 1 + 3 = 22. (3) 1 + 3 + 5 = 32. (4) This can be continued for every number, n. So, (5) 1 + 3 + 5 + … + (2n – 1) = n2. Claims 1 – 3 are verified by the diagram. Claim 4 is difficult to see in the given configuration; but one could say that it is an induction based on claims (1 – 3). So, (4) follows, though only inductively.

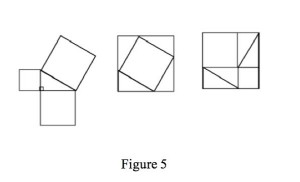

As a different case, consider an oft cited proof of the Pythagoren Theorem (Figure 5). I must confess that when I first saw this collection of diagrams, I did not see it as in any way connected to the Pythagorean Theorem.

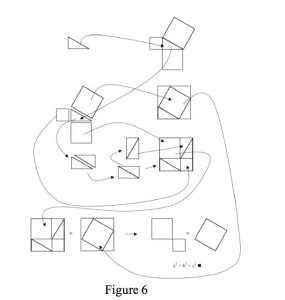

Since that first experience, though, I have had the opportunity to discuss this proof with my daughter who was learning geometry in high school. As an experiment, I gave her the set of figures and asked what she thought. Like my first experience, she didn’t know what to make of the collection. I then gave her the collections of figures labeled Figure 6 below. The arrows represented lines of dependency. In this way, I gave her a way to read the figures. Moreover, this collection also contains the conclusion explicitly. Whether she understood the collection clearly, I cannot say. But I can say that she read through it with delight. More importantly, though, she had questions. She wanted to know what lines were a, b, and c respectively. She wanted to know whether the common notions from her geometry class were common to this collection, etc. From her questions, I constructed the following argument. Let the original triangle be a right triangle; label it T0. Label the hypotenuse c. Label the vertical side a, and the horizontal side b. Let the squares built on the sides of a, b, and c be a2, b2 and c2, respectively. Construct triangles T1 – 4 congruent to T0. This was the setup of the argument. All of these claims are stipulated both as claims and as elements of the collection of figures. Now, manipulate the figure such that you construct a square out of a2 and b2 such that the missing pieces are filled in by the Triangles T’1-4. This is stipulated. Next, construct a square using c2 and the triangles T1-4. This too is stipulated. Now, T1-4 is equivalent to T’1-4. This is a basic equivalency. Notice that the sides of the two squares are (a + b) units long. This is true of both cases. You can see it in the figure. Hence, the figure verifies or corroborates this claim. Finally, if you subtract the four triangles from each square, the remaining pieces are equivalent. On one side a2 + b2 remains, on the other it is c2: as verified by the diagram. To generalize the result, one needs a further claim: we could redo these manipulations on any right triangle. From this, it follows that the result holds generally. This isn’t a proof because the claim regarding the reconstruction of the elements on different right triangles isn’t justified by the collection of figures. Instead, the original construction may provide evidence in the form of know-how for the reconstruction on a different right triangle. And if this is correct, then the argument could be reconstructed as follows. (1) Squares constructed out of the sum of the squares of the two sides of a right triangle and four triangles equivalent to the original triangle and the square constructed on the hypotenuse of the right triangle and four triangles equivalent to the original triangle are equivalent. (2) Since the constructed squares are equivalent, subtracting the four triangles from each square will result in equivalent areas remaining. (3) The result of such subtraction leaves (a2 + b2) and c2 respectively. Hence, (4) for this particular triangle (a2 + b2) = c2. (5) This construction can be reiterated on other right triangles. Hence, (6) (a2 + b2) = c2.

This is a general method for explaining putative figurative proofs: reconstruct them as arguments for which the figures function as evidence for (some of the) claims in the argument. This has the advantage that one need not construct a logic that allows for figurative elements within the syntax of well-formed formulae. Indeed, the logic of figurative arguments will be the logic of any other natural language arguments. One may worry that the reconstruction of the figurative proofs as verbal arguments is not faithful to the actual practice involving such proofs. To the contrary, if you have tried to teach the proofs in Nelsen’s book (Nelson 1993) or the diagrammatic examples in Brown’s essay or his book (Brown 1999) to undergraduates, you probably ended up reconstructing the proofs along the lines I suggest above.

There is one caveat, however. Some of the visual proofs are immediate. That is, they aren’t mediated by intermediate steps. Once the figure is properly prepared, the conclusion is verified by looking at the diagram and not by reasoning through intermediate steps. This, however, does not undermine the method. Rather, this simply points to the actual use of the diagram. A diagram or figure verifies a claim or claims. In the case of an immediate proof, it verifies the conclusion rather than some reason or premise.

Finally, I want to consider some objections that have been levied against diagrammatic reasoning to see whether they undermine the account I prefer. The objections are: (1) The resulting arguments aren’t proofs as the resulting arguments are defeasible. And, (2) The visual elements might be seriously misleading. Regarding (1), I simply accept the criticism. However, it doesn’t undermine my account because I grant that these aren’t proofs. Instead, I am interested in a wider variety of mathematical reasoning. The objection must surely be answered by anyone committed to the notion that reasoning that makes essential appeal to visual elements are proofs, that is not the view I defend and hence the objection misses my account.

Regarding the possibility of misleading diagrams, I can think of two sources. On the one hand, a diagram might be seriously misleading if it is poorly drawn. I liken such cases to shoddy photographs in legal or scientific contexts. I don’t find this type of difficulty unduly worrisome. For, insofar as the figures merely verify, corroborate or refute some claim that is used in an associated argument, the failure to verify in a particular case does not undermine the method. Rather, it seems like this possibility makes the reasoning that results from figurative elements much more like argumentation in other realms. Every argument is assessed on two dimensions: form and content. The poorly drawn figures affect the content of the resulting arguments but not the form.

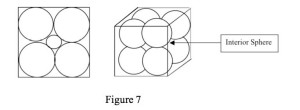

Alternatively, there might be something conceptually wrong with diagrams generally. I think this is hinted at (though not in terms of being a problem) in Brown’s example of a “seriously misleading” figurative proof (Brown 1997, p. 178) (See Figure 7).

He begins by considering a figure constructed from four circles in a particular configuration. One can see that the configuration has the property that a fifth circle constructed so that it touches each of the original circles would itself be contained by a circumscribing square. He then considers the same result extended to three dimensions. He claims that, “Reflecting on these pictures, it would be perfectly reasonable to jump to the ‘obvious’ conclusion that this holds in higher dimensions.” (Brown 1997, p. 178) But the result fails in higher dimensions. I’ve argued elsewhere (Dove 2002) that this isn’t a failure of the diagram. Rather, it is a failure of an implicit premise in the proof: what holds in two and three dimension will hold at higher dimensions. This is surely false. So, it wasn’t the pictures that mislead.

5. Conclusion

I have argued that the use of diagrams and figures in mathematics can sometimes be explained by analogy with the use of photographs in science and the law. The figurative elements verify, corroborate or refute claims in the associated arguments. Since the associated arguments are in the vernacular, as opposed to within some language that allows figurative elements to be proper components of sentences, the logic of these arguments should be mundane. The figures are used in the same way that images are used in other realms, e.g., photos in the law and in science. Hence, the use is not special and does not require one to treat these elements specially. As such, this makes more sense of the actual practice of mathematics than accounts that require occult faculties or specialized vocabularies. I find this result doubly satisfying. On the one hand, it makes room for some visual elements within argumentation theory and informal logic. Of course, this is only part of the story regarding arguments. As stated above, evidentiary uses of visual elements cannot explain the use of images in editorial cartoons, commercials and the like. On the other hand, the account of visual evidence as verifier etc., when applied to the case of diagrams in mathematics, solves a long-standing problem for mathematical practice. Namely, if diagrams aren’t a legitimate component of mathematical reasoning, why are so many mathematical texts littered with them? The answer, of course, is that they are a legitimate part of the reasoning. Their role, however, isn’t one of premise, but of evidence.

REFERENCES

Birdsell, D., & Groarke L. (1996) Toward a theory of visual argument. Argumentation & Advocacy 33, 1-10.

Birdsell, D., & Groarke L. (2007) Outlines of a theory of visual argument. Argumentation & Advocacy 43, (3-4), 103-114.

Blair, A. (2004). The Rhetoric of Visual Arguments. In M. Helmers & C. Hill (Eds.), Defining Visual Rhetorics (pp. 41-61). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Brown, J. R. (1999). Philosophy of Mathematics, London and New York: Routledge.

Brown, J. R. (1997). Proofs and Pictures. Brit. Journal for Phil. Sci., 47,161-181.

Dove, I. (2002). Can Pictures Prove? Logique et Analyse, 179-180, 309-340.

Fitzpatrick, J.W., et al. (2005). Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) Persists in Continental North America. Science 3, (309, 5727), 1460 – 1462.

Fleming, D. (1996). Can Pictures Be Arguments? Argumentation and Advocacy, 33, 1, 11-22.

Franklin J. (1987). Non-Deductive Logic in Mathematics. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 38 (1),1-18.

Groarke, L. (1996). Logic, Art and Argument. Informal Logic 18, (2-3), 105-131.

Groarke, L. (2002). Towards a pragma-dialectics of visual argument. In: Van Eemeren, Advances in Pragma-Dialectics. Amsterdam: SicSat, and Newport News:Vale Press.

Johnson, R.H. (2005). Why “Visual Arguments” Aren’t Arguments. In: Hans V. Hansen, Christopher Tindale, J. Anthony Blair and Ralph H. Johnson (Eds.). Informal Logic at 25, University of Windsor, CD-ROM.

Johnson, R. H. (2000). Manifest Rationality: A Pragmatic Theory of Argument. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Manders, K. (2008). The Euclidean Diagram. In P. Mancosu (Ed.), Philosophy of Mathematical Practice. Oxford: Claredon Press.

Mouser, J.E., & Philbin J. (1957). Photographic Evidence-Is there a recognized basis for admissibility? Hastings Law Journal, 8, 310 – 314.

Nelsen, R.B. (1993). Proofs Without Words: Exercises in Visual Thinking. Washington DC: Mathematical Association of America.

Walton, D., Reed, C., & Macagno, F. (2008). Argumentation Schemes. New York: Cambridge University Press.