ISSA Proceedings 2010 – Concepts And Contexts – Argumentative Forms Of Framing

1. Introduction

1. Introduction

The concept of framing – and the underlying theoretical mindset – is familiar to a number of scholarly fields and discussions. Although the notion of framing has its roots in sociological thinking, it has made its way into many other fields. Thus, framing is applied to management studies (Hodgkinson et al., 1999; Conger, 1991; Smircich & Morgan, 1982), rhetorical studies (Kuypers, 2009; 2006; Cappella & Jamieson, 1997), media studies (de Vreese & Elenbaas, 2008; Scheufele, 1999; Entman, 1993; Iyengar, 1991), and linguistics (Tannen (Ed.), 1993) – to name but a few of the most relevant fields. Framing, then, has undergone quite an expansion from being conceived as a tool for micro-analysis of social interaction to its current broad interpretation and diversified application.

When taking this development into account it is not surprising that framing is also to be found within the field of argumentation and that it is used in various ways within this field. An overview of argumentation studies shows that use of the concept is distributed along a continuum from intuitive and implicit to theoretical and explicit. At one end of the spectrum we find a commonsensical use of framing that is often neither expanded nor explained (see inter alia Bertea, 2004; Freeman, 2001; Garrett, 1997). At the other end of the spectrum we find contributions that take their starting point in framing (and the literature on the concept) and bring it to bear on discussions that are of relevance to the theory of argumentation. Be it in the understanding of ‘playful argumentation’ (Hample, Han & Payne, 2009), in the development of ‘interpersonal arguments’ (Hample, Warner & Young, 2008) or in the conceptualization of ‘non-deductive argumentation’ (Wohlrapp, 1998) – again, only highlighting a few relevant examples.

Framing is used to define a number of processes and functions that oftentimes do not exist on the same plane of theoretical reasoning or level of empirical analysis. As we will unfold in the following, framing is sometimes thought of as cognitive processes of understanding while it is seen as communicative tools in other contexts. The notion of framing is, in other words, not a simple, clear cut one; a point which is often stressed in the literature. Robert Entman, for instance, begins from the assumption that “despite its omnipresence across the social sciences and humanities, nowhere is there a general statement of framing theory that shows exactly how frames become embedded within and make themselves manifest in a text, or how framing influences thinking” (1993, p. 51). Michael Hoffman laments that “…in spite of its prominence in scientific discourses, the concept of ’framing’ and its derivatives are used in very different ways. Obviously, there is no shared understanding of what ‘framing’ exactly means, and what kind of activities can count as ‘framing’ and which cannot” (2006, p. 2). And Kirk Hallahan sums up both the potentials and the problems: “although a theoretically rich and useful concept, framing suffers from a lack of coherent definition” (2008, p. 209). The question is, therefore, what we actually gain from introducing framing into various subjects and fields? If framing is not a clear concept, the subject it is intended to illuminate will not become clearer.

In an attempt to solve these issues in the context of argumentation and show how the notion of framing may become more useful to argumentation scholars we will reverse the typical order of application. Rather than applying the notion of framing to one or the other aspect of argumentation we will try to explain and clarify framing by starting from the field of argumentation. It is possible to draw parallels between classical argumentative concepts and the concept of framing (Pontoppidan, Gabrielsen & Jønch-Clausen 2010; Just & Gabrielsen 2008), and it is this line of thinking that we will build upon in the following. What may we learn about the types of argumentative moves that may be typified as framing by viewing them through the lens of classical theories of argumentation?

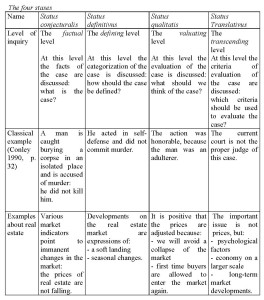

In order to answer this question we introduce the classical rhetorical theory of stasis, the teaching about how to locate the disputed point in a debate, as a means of clarifying and ordering what is meant by framing. There are four stases dealing with 1) fact (status conjecturalis), 2) definition (status definitivus), 3) quality (status qualitatis), and 4) jurisdiction or transcendence (status translativus), and we argue that when filtered through the stases framing refers to at least two different argumentative moves or patterns. One is an internal definition or categorization of the concepts in question; the other is an external shift or transcendence in the context of the case. As an example of the internal definition/categorization one can, for instance, argue that the recent fall in the prices of real estate that has affected most of the Western hemisphere was not a bursting bubble, but a natural correction, thus redefining the matter and reframing the issue. And as an example of the external shift/transcendence of context one can argue that a house should not be bought as an investment, but because it is the house of one’s dreams, thus changing the context of the argumentation and shifting the issue from an economic to an emotional frame.

In making the link between framing and the theory of stasis, we do not claim to offer a comprehensive analysis of the argumentative forms involved in framing – we only claim that the theory of stasis exposes that the notion of framing contains (at least) two different types of moves. Both definition and transcendence are argumentative forms of framing, but they point to two quite different ways in which a matter may be framed. Furthermore, we indicate that while framing is not just one argumentative move, it is nevertheless a particular type of argumentation which does not seem to include the issues of fact and quality as these are defined in the theory of the stasis. Thus, applying the stases to the field of framing both allows us to point to what argumentative frames are and what they are not.

The issue of how the stases may relate to and help clarify the notion of framing is primarily a theoretical one, but we will illustrate the notion that the stases point to basic argumentative forms of framing by means of generic examples constructed on the basis of the Danish public debate on the value of real estate – as we have already done in the initial example of how the stases of definition and transcendence may be linked to framing.

Before we begin our exploration of framing from the viewpoint of the stases, we unfold our initial claim; namely, that the concept of framing is a pluralistic one. Different scholars have stressed different aspects of the concept and developed it in different directions, and we will present a few highlights from the discussion of what framing is and how it should be studied. Following the introduction to the concept of framing as such we will delimit our notion of framing as a form of argumentation from the broader understandings of framing and thereby offer a definition of what is meant by framing in this particular study of the concept. Then we will briefly introduce the theory of stasis and go on to discuss how the stases may explain and typify what framing is.

2. Framing: A pluralistic concept

Since Erving Goffman introduced the concept of framing, it has not only been developed and diversified, but also repeatedly challenged. Much of the subsequent debate derives from the great explanatory potential, but also the great vagueness of the concept as Goffman defined it. Frames, to Goffman, are the “…principles of organization which govern events – at least social ones – and our subjective involvement in them” (1974, p. 10-11). More specifically, frames are the “schemata of interpretation” that allow people to partake in social interaction; frames are means of locating, perceiving, identifying and labeling experiences that provide the interpreter with an understanding of what is going on and how he/she should react to it (1974, p. 21). In Goffman’s microsociological conception, then, frames help individuals structure and interpret their surroundings, but this does not mean that frames are purely cognitive phenomena. Rather, Goffman suggests that frames do not just exist in our heads, but may be read out of – or perhaps into – the social interaction (1981, p. 62). Here, crucial questions arise: Are frames cognitive or communicative phenomena? And if they are both, how may they be studied as such?

Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky provide one possible answer to these questions. Kahneman and Tversky set up experiments testing peoples’ reactions to a text in which specific words were changed. Thus, they have shown that people choose different courses of action according to the positive or negative framing of a matter; whether an event is framed in terms of ‘saving’ or ‘dying’ is literally a matter of life and death (Kahneman & Tversky 1984). Whereas this psychological take on the issue includes the communicated dimension of framing as the independent variable (the factor that is changed in order to measure people’s reactions to the change), it is the cognitive dimension that is at the heart of the research.

A more explicit focus on the communicative dimension of framing is found in the work of cognitive linguists such as George Lakoff. Although maintaining the cognitive importance of frames, Lakoff focuses more on what causes the cognition than on the cognitive process as such; that is, his focus is on language. Lakoff coins the term surface frames for the communicative dimension of framing, and he studies how specific changes in the surface frames may alter our perception of the phenomena in question (Lakoff, 2004; 1999). His prime examples stem from political debate in the US, and he argues that the Democratic Party has overtaken frames that are to the advantage of the Republican Party instead of establishing their own alternative frames. For instance, framing the discussion on whether or not to lower the taxes in terms of ‘tax relief’ means that taxation is basically seen as a burden, and this gives the Republicans the upper hand (Lakoff, 2004, p. 24-26). Although Lakoff is concerned with the effects of framing, he does not conduct experimental research, but focuses on the ways in which topics are framed in communication and what frames come to dominate public debates (and other communicative processes).

Within media studies a combination of the foci on communication and cognition is seen in several influential investigations. For instance, Shanto Iyengar and Donald R. Kinder (1987) and Joseph Cappella and Kathleen Hall Jamieson (1997) have conducted major studies that both identify dominant news frames and people’s reactions to such frames. In this context the notion of framing is linked to that of agenda setting; what is presented in the news, how is it presented, and what are the consequences? (Dainton & Zelley, 2005, p. 199-200). Hence, there is a movement from the institutionalized forms of communication of the news media to the perception of the news that takes place in the minds of individual recipients.

The movement from media to recipients that characterizes studies of the communication and reception of news frames points to another crucial ambiguity in Goffman’s conception of frames: are they individual or are they social? Goffman himself emphasized the primacy of the social, but nevertheless studied frames in their individual manifestations (1974, p. 13). The application of frames in media studies seems to begin from the social level and move to the individual level. In focusing on social movements Robert Benford and David Snow (1988; 2000) have performed a similar move. Furthermore, they emphasize how frames may provide the backdrop of not only individual, but also social action. Thus, the locus of framing is placed at the level of “situated social interaction,” and quoting Mikhail Bakhtin Snow and Benford define framing as a dialogical phenomenon that exists “not within us, but between us” (2005, p. 205).

Addressing the issue of the individual or social character of framing, then, implicitly tackles the issue of their cognitive or communicated status as well. If frames are social, they are also communicated, existing as forms and patterns of dialogue and debate before they come to organize and define the individual’s interpretation of social actions and events. This does not mean that studying cognitive reactions to or applications of frames becomes uninteresting, but it means that analysis of the communicated – or surface – frames is the place to start.

3. Argumentative frames

As our short review of the field shows, framing is a rather broad and slippery concept. Goffman’s introduction of the concept laid the ground for this ambiguity, and two issues have been particularly central to the subsequent discussions on the definition and use of framing: are frames cognitive or communicative processes? And are they individual or social phenomena? As indicated above, different schools, fields, and perspectives have placed the emphasis differently, wherefore there are today both theories that view frames as pertaining to the level of individual cognition and theories that highlight the social and communicative aspect of framing. In other words: one concept, many interpretations.

In the following we will adopt a narrow focus, and instead of seeking direct answers to the traditional issues of framing – cognitive or communicative, individual or social – we will look at framing as argumentation and ask: which argumentative forms does framing represent? Should one particular form of argumentation or several different forms be linked with framing? In other words, what argumentative moves are performed when one argues by framing?

Before answering these specific questions, however, it seems necessary to consider what we generally mean by framing in an argumentative context. We must make an initial distinction between the types of argumentative moves that may be linked to framing and the types that may not. What we are looking for is a tentative and pragmatic definition and delimitation of the phenomenon of argumentative framing. The following considerations, then, are meant as a means of pointing at the type(s) of argumentation that will be analyzed and discussed in the following, not as an exhaustive list of argumentative frames, let alone a definition of framing as such.

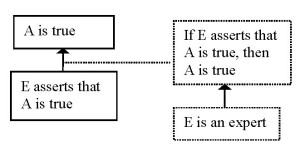

For our specific purposes Jim Kuypers’ rhetorical approach to framing offers a useful starting point. According to Kuypers “framing is a process whereby communicators, consciously or unconsciously, act to construct a point of view that encourages the facts of a given situation to be interpreted by others in a particular manner…” (2006: p. 8). Several keywords of this quote point to our understanding of what is at stake in argumentation that hinges on framing. First, the word ‘construct’ shows that we are dealing with argumentation that orders or forms the object of the argumentation – as opposed to argumentation that works by inferring or deducing the relevant conclusions. Second, the word ‘interpreted’ suggests that argumentation based on framing is meant to make the audience view the object in a certain way – again, in contrast to making the audience infer particular conclusions. Finally, framing-based argumentation is characterized by its starting point in ‘a given situation’, not a given set of premises.

It is the move from the case to its premises that is at stake in framing-based argumentation – not the move from premises to conclusion which is the point of other argumentative forms. The argumentative forms of framing begin from a given situation and work by constructing a certain perspective that makes the audience interpret the case in a specific manner. Thus, framing is set apart from argumentative forms as such; the notion comes to encompass a certain set of moves within argumentation – a certain way of arguing. The type of argumentation which relates to framing and which we will seek to unpack by means of the theory of stasis, then, is argumentation aimed at changing and/or deciding what is to count as the premises of a case.

4. The teaching of stasis

The coupling of framing with argumentation aimed at changing and/or deciding what is to count as the premises of a case narrows in the argumentative field to which the concept holds relevance. However, it is not necessarily a singular definition pointing to one and just one argumentative form. Even when starting from a given situation, there are several possible means of constructing a perspective that will make the audience interpret the case in a certain way. In the following we will explore different possibilities; that is, specific argumentative forms of framing. Taking our starting point in the theory of stasis we will show that framing-based argumentation can be divided into (at least) two groups and that these groups refer to quite different modes of reasoning. In order to do so we will first present the rationale behind the classical theory and introduce the four stases that form the centerpiece of it. Then we will argue that two of the four stases – status definitivus and status translativus – represent two distinct forms of framing-based argumentation, whereas the other two stases – status conjecturalis and status qualitatis – should not be seen as framing devices. In unpacking the argumentative forms of framing that may be associated with status definitivus and status translativus we hope to establish a distinction that may help clarify what argumentative framing actually is and what it can be used for.

As is the case with other classical rhetorical concepts and systems, the origin of the theory of stasis is somewhat disputed – just as discussion on the right interpretation of this theory prevails. In a work that is now lost Hermagoras supposedly was the first to present the theory of stasis as we know it today; that is to say, as a theory the purpose of which is to determine the central issue of dispute in a given case (Hohmann, 2001, p. 741; Braet, 1987, p. 79). The central question, then, is: at what level should discussion be conducted? There is some dispute as to how many levels the answer to this question should result in: three or four? (Hohmann, 1989). In the Greek tradition as introduced by Hermagoras and elaborated by Hermoganes four distinct stases were applied (Nadeau, 1964), but in the Roman tradition as primarily represented by Cicero and Quintilian only three stases were employed (Cicero De Oratore II, p. 113; Orator, p. 45; Quintilian Institutio Oratoria, book VII; for an exception to this rule see Cicero De Inventione I, p. 10). The reason for only mentioning three stases was a desire to present a system that could be applied to rhetoric broadly, and the fourth status was said to relate only to the forensic genre (Hohmann, 2001, p. 742-743). As we will explain below, we tackle the issue of the fourth status differently and, therefore, propose to include all four in broader conceptualizations of the teaching of the stasis and not only in the version of the theory that pertains narrowly to legal disputes.

The theory of stasis, then, lists four possible levels of dispute – four different stases: status conjecturalis, status definitivus, status qualitatis, and status translativus. In the following table we present the four stases, the level at which each status operates, a classical example, and examples from the debate on the real estate market so as to begin the coupling of our modern example of choice and our theoretical focal point.

All four stases make for interesting forms of argumentation, but status definitivus and status translativus are of particular importance to the present investigation. These two stases may be identified as argumentative forms of framing: argumentation based on categorization and definition as well as argumentation based on displacements of the employed criteria of evaluation basically function to make the case appear in a certain manner, to make the audience interpret the various elements of the case in one way rather than the other – the central issue of our definition of framing. In other words, we claim that both status definitivus and status translativus are movements from the case to the premises; it is the understanding of the case as such that is at stake in these two forms of argumentation. In this sense, the two stases resemble Kuypers’ observation that framing is about content as well as context (2009, p. 188), a point which we will explore in further detail below, but first let us consider the other two stases in order to explain why we do not think they are argumentative forms of framing.

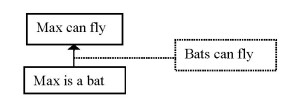

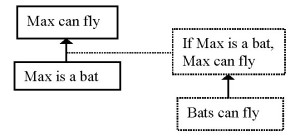

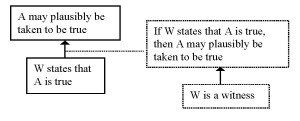

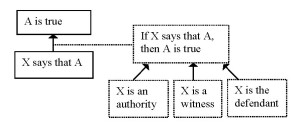

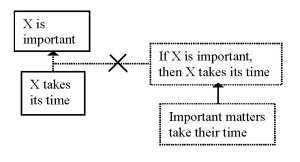

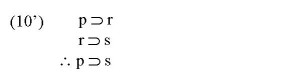

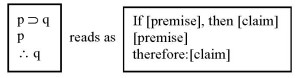

Status conjecturalis and status qualitatis are classical enthymematic arguments in which the conclusion follows from the premises and, therefore, do not appear to be argumentative forms of framing. Two explications of the warrants that are often implicit in practical use of the stases may illustrate this: if the experts say there is no fall in prices, there is no fall in prices (conjecturalis); if the prices are falling, first-time buyers will benefit (qualitatis). In both cases the arguments follow inferential patterns rather than performing the establishment or shift in the premises of interpretation that is characteristic of framing. This is not to say that it would be impossible to reinterpret status conjecturalis and status qualitatis as argumentative forms of framing. We only argue that status definitivus and status translativus take up a special position since they are immediately compatible with the notion of framing. Status definitivus and status translativus also immediately point to two distinct forms of framing and this is what makes it particularly interesting to unfold them here.

The interpretation of status definitivus as an argumentative form of framing follows more or less directly from the usual definitions of definitivus on the one hand and framing on the other. First and foremost the term ‘definition’ is an explicit part of many definitions of framing (most notably Entman 1993, p. 52). A definition of the disputed issue – or case in question – is central to the audience’s reading and interpretation of it. By placing a matter in one category, other categories are rejected. Moreover, definitions usually work at the level of specific words or concepts at which attempts at framing is arguably most clearly visible (cf. Lakoff’s notion of surface frames that is tied to a choice of words).

The discussion on how to categorize developments on the real estate market clearly illustrates how framing through definition works at the level of words and concepts: is an apparent fall in prices a bubble bursting, a soft landing or a natural correction? Each definition becomes possible by highlighting some elements of the case rather than others, and, in turn, functions to make the audience highlight the same elements when interpreting the matter. The choice of definition – or frame – actualizes one set of premises rather than other possible starting points of argumentation and alters the interpretation of the case that audiences are invited to make.

At its most basic, the strategy of definition can be described by the formula A is B wherefore this argumentative form of framing is internal to the case. As illustrated above, a definition is based on weighing the different elements of the case against each other: is the fall in prices accelerating (a sign of a bursting bubble), is it a slow movement (closer to the notion of the soft landing), was it long expected (a natural correction)? And how may the use of definitions induce audiences to interpret the case as either a fast, a slow, or an expected development?

To conclude the discussion of status definitivus, it is by considering, selecting, and labeling the available information that the case may be defined. When framing through definition, then, focus is directed inwards at the different elements of the case and the various categories that it is possible to apply to these elements. The form of framing that is exposed through consideration of status definitivus is about the conceptualization and categorization of the case. Thus, the interpretation of the case is steered or given direction by accentuating some elements of the case and ignoring others.

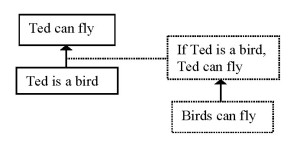

The interpretation of status translativus as a form of framing is, perhaps, less obvious. Classically understood, this status is a movement of the physical setting of a case: for instance, from the High Court to the Supreme Court or from a court of justice to ‘the court of the people’. However, we believe that translativus may also be understood as a change of scenes in a broader, metaphorical sense (Just & Gabrielsen 2008). Here, we follow the line of thinking that suggests this fourth status must be redefined in order to be applied to a broad range of contemporary issues rather than just the juridical genre of classical times (Gross 2004; Kramer & Olson 2002). Instead of delimiting translativus to being about deciding who should judge, we see it as being more broadly about deciding the criteria for judgment.

Thereby, status translativus becomes a general strategy that may be used outside of the narrowly forensic context. Moreover, this widening of the strategy makes the interpretation of translativus as an argumentative form of framing more apparent: changing the criteria used in judging a case is a basic way of influencing how the audience interprets the case. When understood metaphorically, changing the scene is akin to framing; it is a strategy that changes the premises of the case.

When this status is used by the participants in the debate on real estate several possible shifts are employed and discussed: should the developments on the real estate market by evaluated in the short or the long term? Should economic or emotional criteria be used as the basis of evaluation? And who should perform the evaluation – sellers, buyers, real estate agents, economists, or some other party? Depending on which frame is used – and which becomes dominant in the debate – the criteria for interpreting and evaluating the case change.

When reinterpreted in this manner status translativus can be described by the formula A should be evaluated on the basis of B, making it an argumentative form of framing that is external to the case. In opposition to definitivus which functions as an internal conceptualization of the case translativus works as an external contextualization. Rather than weighing the elements of the case and including/excluding them in the definition, the strategy of translativus works by setting up the factors or criteria which the case is held up against. As exemplified above the real estate market may be held up to the standard of making profit which is a frame of private economy, but it may also be reinterpreted as a matter of national economy or the economic frame may be swapped for an emotional one: buy with your heart rather than your wallet.

In sum, framing by means of status translativus directs attention outwards at the various factors with which the case should be associated and/or the criteria with which the case should be evaluated. The form of framing that is exposed through consideration of translativus is focused on the contextualization of the case. The interpretation of the case is influenced through a change of the external criteria on which interpretation and evaluation should be based.

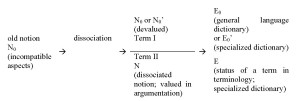

As the examples of how status definitivus and status translativus may be applied to the real estate market indicate the basic formulas of the two stases are rather similar at the formal level. This becomes most apparent when considering the type of definition that may be labeled dissociative (Perelman & Olbrechts-Tyteca 1969, p. 444): A is not B, but C; we are not witnessing a recession, but a deceleration. Almost the same extension may be used in the case of the basic formula of translativus: A should not be judged in terms of B, but C; you should not buy a house as speculation, but because you need a place to stay. The similarity in the two stases shows that they are both argumentative forms of framing, but the examples also illustrate the difference of the two stases as frames: one frames the case in terms of its internal concepts, the other frames it in terms of its external context.

5. Conclusion

We have drawn attention to the ways in which status definitivus and status translativus function as argumentative forms of framing. The levels of dispute that they represent are both about how to interpret the case – and about what should be the premises of the case – and it is in this sense that they may be understood as framing. However, the two stases do not represent the same form of framing; rather, internal definition and external transcendence are quite different moves. Thus, we have identified two distinct argumentative forms of framing that may clarify what framing is.

Such clarification is important because the notion of framing has been an export success. From its origin in the microsociological work of Erving Goffman it has, as we have briefly sketched out, been applied within a wide variety of fields. The concept of framing has proved to contain a large explanatory potential, but it has also become a diffuse and contested concept, and scholars have repeatedly called for a clarification of it.

By reversing the direction of import-export and applying the teaching of stasis – a center-piece of classical argumentation theory – to the notion of framing we hope to have contributed to the clarification of framing in the context of argumentation. Furthermore, we hope that this movement from argumentation theory to framing may be followed up by taking the revised and refined notion of framing back to the field of argumentation, that it will now prove to be both more readily applicable to studies of practical argumentation, and that such applications may be more rewarding.

In discussing framing in terms of the stases we have both pointed out that not all forms of argumentation are framing and that there is more than one argumentative form of framing. Thus, we do not believe status conjecturalis and status qualitatis to be argumentative frames, whereas we believe status definitivus and status translativus to represent distinct argumentative frames. We are by no means certain that there are only two argumentative forms of framing, but the internal framing of concepts that emerges from the consideration of status definitivus and the external framing of contexts that is pointed out through the reconceptualization of status translativus are in our opinion very basic and important argumentative forms of framing. The identification of these two forms may form the starting point for both applications of the concept of framing in studies of practical argumentation and further refinements of the concept in terms of argumentation theory.

REFERENCES

Benford, R. D., & Snow, D. A. (2000). Framing processes and social movements: An overview and assessment. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 611-639.

Bertea, S. (2004). Certainty, reasonableness and argumentation in law. Argumentation, 18(4), 465-478.

Braet, A. (1987). The classical doctrine of status and the rhetorical theory of argumentation. Philosophy and Rhetoric, 20(2), 79-93.

Cappella, J. N., & Jamieson, K. H. (1997). Spiral of Cynicism. The Press and the Public Good. New York: Oxford University Press.

Cicero, M. T. (1993). De Inventione. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Loeb Classical Library. Harvard University Press.

Cicero, M. T. (2003a). De Oratore. Retoriske Skrifter I. Odense: Syddansk Universitetsforlag.

Cicero, M. T. (2003b). Orator. Retoriske Skrifter II & III. Odense: Syddansk Universitetsforlag.

Conger, J. A. (1991). Inspiring others. The language of leadership. Academy of Management Executive, 5(1), 31-45.

Conley, T. M. (1990). Rhetoric in the European Tradition. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Dainton, M., & Zelley, E. D. (2005). Applying Communication Theory for Professional Life. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

de Vreese, C. H., & Elenbaas, M. (2008). Media in the game of politics: Effects of strategic metacoverage on political cynicism. International Journal of Press/Politics, 13(3), 285-309.

Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Towards clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43, 51-58.

Freeman, J. B. (2001). Argument structure and disciplinary perspective. Journal of Argumentation, 15(4), 397-423.

Garrett, M. M. (1997). Chinese buddhist religious disputation. Argumentation, 11 (1), 195-209.

Goffman, E. (1974). Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience. London: Harper and Row.

Goffman, E. (1981). A reply to Denzin and Keller. Contemporary Sociology, 10 (1), 60-68.

Gross, A. G. (2004). Why Hermagoras still matters: The fourth stasis and interdisciplinarity. Rhetoric Review, 23, 141-155.

Hallahan, K. (2008). Seven models of framing: Implications for public relations. Journal of Public Relations Research, 11(3), 205-242.

Hample, D., Han, B., & Payne, D. (2009). The aggressiveness of playful arguments. Argumentation, online first, 1-17.

Hample, D., Warner, B., & Young, D. (2009). Framing and editing interpersonal arguments. Argumentation, 23(1), 21-37.

Hodgkinson, G. P. et al. (1999): Breaking the frame: An analysis of strategic cognition and decision making under uncertainty. Strategic Management Journal, 20, 977-985.

Hoffman, M. (2006). Framing: An epistemological analysis. Retrieved July 13th 2010 from http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=916007.

Hohmann, H. (1989). The dynamics of stasis: Classical rhetorical theory and modern legal argumentation. The American Journal of Jurisprudence, 34, 171-197.

Hohmann, H. (2001). Stasis. In T. O. Sloane (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Rhetoric (pp. 741-745). New York: Oxford University Press.

Iyengar, S. (1991). Is Anyone Responsible? How Television Frames Political Issues. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Iyengar, S., & Kinder, D. R. (1987). News that Matters. Television and American Opinion. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Just, S. N., & Gabrielsen, J. (2008). Boligmarkedet mellem tal og tale. Rhetorica Scandinavica, 48, 17-36.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1984). Choice, values and frames. American Psychologist, 39, 341-350.

Kramer, M. R., &. Olson, K. M. (2002). The strategic potential of sequencing apologia stases: President Clinton’s self-defense in the Monica Lewinsky scandal. Western Journal of Communication, 66, 347-368.

Kuypers, J. A. (2006). Bush’s War. Media Bias and Justifications for War in a Terrorist Age. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Kuypers, J. A. (2009). Framing analysis. In J. A. Kuypers (Ed.), Rhetorical Criticism. Perspectives in Action (pp. 181-204). Lanham: Lexington Books.

Lakoff, G. (1999). Moral Politics: How Liberals and Conservative Think. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Lakoff, G. (2004). Don’t Think of an Elephant: Know Your Values and Frame the Debate. Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing Company.

Nadeau, R. (1964). Hermogenes’ On Stases: A translation with an introduction and notes. Speech Monographs, 31(4), 361-424.

Perelman, C., & Olbrechts-Tyteca, L. (1969). The New Rhetoric. A Treatise on Argumentation. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

Pontoppidan, C., Gabrielsen, J., & Jønch-Clausen, H. (2010). Topik – Et retorisk bidrag til den kritiske journalistik. Nordicom Information, 32(1), 47 – 59.

Scheufele, D. A. (1999). Framing as a theory of media effects. Journal of Communication, 49(1), 103–122.

Snow, D. A. & Benford, R. D. (1988). Ideology, frame resonance, and participant mobilization. International Social Movement Research, 1, 197–217.

Snow, D. A., & Benford, R. D. (2005). Clarifying the relationship between framing and ideology. In H. Johnston & J. A. Noakes (Eds.), Frames of Protest. Social Movements and the Framing Perspective (pp. 205-212). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Smircich, L., & Morgan, G. (1982). Leadership: The management of meaning. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 18(2), 257-273.

Tannen, D. (Ed.) (1993). Framing in Discourse. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wohlrapp, H. (1998). A new light on non-deductive argumentation schemes. Argumentation, 12, 341-350.