ISSA Proceedings 2010 – The Challenge Of Studying Argumentation In Context

1. Introduction

1. Introduction

Recent research has shown increasing interest in contextualised argumentation, because, as some authors remark, argumentation is always a context-bound communicative activity (van Eemeren et al. 2009). A number of signs – such as, for example, the establishment of an international doctoral program on argumentation practices in different contexts (Argupolis, www.argupolis.net) – prove the increasing interest for the study of contextualised argumentation within the community of argumentation scholars. At the same time, the importance of the argumentative perspective is also recognised in a number of other disciplines, which become more and more open to interdisciplinary cross-fertilisation (see for example Muller Mirza and Perret-Clermont 2009 about argumentation in science education and learning). We could summarise the situation as a progressive convergence of interests: the interest of argumentation theorists for the study of context and the interest for argumentation arisen in a number of contexts traditionally tackled by various other disciplinary perspectives.

The general view at the basis of the study of contextualised argumentation is that argumentation is a form of communicative interaction by means of which social realities – institutions, groups and relationships – are constructed and managed. People develop argumentation in numerous purposeful activities: to make sound and well-thought decisions, to critically found their opinions, to persuade other people of the validity of their own proposals and to evaluate others’ proposals. These activities are bound to the contexts in which they take place and are significantly determined by these contexts; thus argumentation too, as the bearing structure of these activities, moulds its strategies in connection with these very different contexts: from families and schools to social and political institutions; from political deliberations to media discourse and journalism; and from social and ethical debates to the economic and financial sphere.

In the framework of this increasing interest, it is worth reflecting on what study argumentation in context means at the theoretical and methodological levels. In this paper, I shall tackle this problem by elaborating on my research in the context of dispute mediation (Greco Morasso 2011). I shall address the results emerged from this work at the level of meta-reflection, trying to show what particular challenges await scholars on argumentation presently.

The paper is organized as follows. I shall first outline the origin of the present research, namely the framework in which this reflection has originated (section 2). Then I shall focus on some specific challenges that await argumentation scholars considering contextualised argumentation (section 3).

2. Argumentation in context: dispute mediation a case in point

The reflections I shall present in this paper largely stem from my involvement in a study on contextualised argumentation about argumentation in dispute mediation. Beside characterizing the role that argumentation plays in dispute mediation (Greco Morasso 2011), this research project constituted the opportunity to reflect more in general on what studying argumentation in context means at the theoretical and methodological levels.

In the original research project, I have been focusing on how argumentation helps fulfil the pragmatic goals of mediation. It was already ascertained that argumentation is to some degree present in dispute mediation (van Eemeren et al. 2003, Jacobs 2002, Jacobs and Aakhus 2002a and 2002b, Aakhus 2003, van Eemeren 2010, Walton and Godden 2005, Walton and Lodder 2005). Yet how argumentation is established in this process of conflict resolution and what the mediator’s role is in this process still remained unexplained. In particular, the “problem” that set my research project into motion concerned the change in attitude that parties experience in a successful mediation process and that brings them to become co-arguers, i.e. rational interlocutors jointly engaged in an argumentative discussion. In fact, when parties enter their first mediation session, they are normally involved in a conflict that they cannot manage by themselves any more. This is typical of mediation (van Eemeren 2010). However, the very nature of mediation implies that parties should make their own decision on their problem, by discussing about it. In this sense, as it clearly emerges when looking at empirical data, parties who have a good mediation process in the end have been able to conduct a fruitful argumentative discussion by themselves. How can this change in attitude – from disputants to co-arguers – happen? How are the parties able to do it? And what is the mediator’s role in triggering this change in attitude?

Such were the questions that guided my interest in argumentation in dispute mediation (Greco Morasso 2011). In this paper, I shall not focus on the specific results about the process of mediation. Rather, this research project will constitute a basis to reflect more in general on the study of argumentation in context. In the next section, I will extrapolate from my personal research experience four main challenges which I believe are to be faced by all scholars interested in argumentation in context.

3. Argumentation in context: current challenges

In this section, I shall turn to discuss four aspects that I derive from reflection on the study of contextualised argumentation carried on in the above-delineated framework (see section 2). I present these aspects as four challenges that argumentation scholars need to face, namely: (3.1) Defining context as a theoretical problem; (3.2) Reconstructing the features of the specific context taken into account in the argumentative analysis; (3.3) Being open to interdisciplinarity and (3.4) Identifying prominent features of argumentation in specific contexts.

Some research about what studying argumentation in context means has been already done (see van Eemeren 2010), but it is fair to say that there is still a lot of work expected to go deeper in the study of argumentation in context. By eliciting these four aspects, I do not claim to present a consistent and exhaustive theoretical picture about the directions of research which can be undertaken to specify the theoretical relations between argumentation and context. Rather I would like to open the discussion on some issues which have emerged as general issues relevant to the analysis of argumentation in context.

3.1. Defining context as a theoretical problem

A first aspect that emerges when considering argumentation in context is that the notion of context itself is still in need of accurate analysis; we still need to highlight how context influences and is influenced by argumentative interactions. The challenge of defining context is certainly a first necessary presupposition to study argumentation in context.

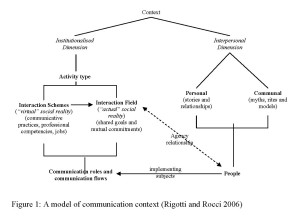

In my opinion, Rigotti and Rocci (2006) have proposed an account of communication context that is particularly apt to be adopted as a working hypothesis to be further developed in studies on contextualised argumentation. I report their graphical overview presentation of the model in Figure 1.

As the authors put it, this account elaborates on the notion of activity type (in terms of van Eemeren and Houtlosser 2005) and expands it in two important ways. In what follows, I shall mention these two extensions, while not considering the whole model in detail; a complete presentation is to be found in Rigotti and Rocci (2006).

First, the concept of activity type is specified into two constituents: the interaction scheme and the interaction field.

Interaction schemes are defined as “culturally shared ‘recipes’ for interaction congruent with more or less broad classes of joint goals and involving scheme-roles presupposing generic requirements. Deliberation, negotiation, advisory, problem-solving, adjudication, mediation, teaching are fairly broad interaction schemes; while more specific interaction schemes may correspond to proper ‘jobs’” (ibid., p. 173)”. An interaction scheme like mediation may be implemented in a series of interaction fields. Albeit the fundamental features of the interaction scheme remain the same throughout its application possibilities, the interaction field contributes to the definition of the actual communication context. In fact, while interaction schemes are virtual competences, interaction fields are pieces of social reality. Interaction schemes cannot but be implemented in different interaction fields; thus we do not have, in practice, the experience of the interaction scheme of “debate” but we know what a “TV debate” or a “parliament debate” is in a specific national and cultural context and at a specific point in time[i]. If we consider the context of dispute mediation as an example, several important differences in its actual implementation depend on the interaction field to which mediation is applied. In this respect, commercial mediation is quite different from, say, family mediation. Thus, a good commercial mediator may prefer not to work with family disputes and vice versa. However, some of the features of mediation are interaction field-invariant: the presence of a third neutral intervenor, the requirement that the decision about the conflict will be made by the disputants rather than imposed by some external authority, etc. are features of this kind. Therefore, it seems appropriate to distinguish between interaction field and interaction scheme to provide a precise account of the context of an argumentative discussion like the one that may arise in mediation. Both dimensions have an influence on the arguers’ strategic manoeuvring (Greco Morasso 2011) but the constraints that they impose may be different.

Second, Rigotti and Rocci’s reconstruction also highlights that the institutional dimension is not the only relevant aspect to describe a communication context; the human beings who actually cover the different institutional roles make a difference for the possibilities of the arguers’ strategic manoeuvring. Certainly, the people who “make” the different activity types are part of those activity types. However, one should not forget that a person may take part in an activity type assuming a certain role – like for example being a mediator – which however does not completely overlap with a full account of her. Human beings precede and overcome their roles, because they have desires, interests and goals that exceed what is expected by the institutionalised context in which they operate. The only partial overlapping between a person’s goal and a role’s goal explains, in some circumstances, conflicts of interests and personal behaviours which are not aligned with the goal of a certain activity type. For this reason, Rigotti and Rocci (2006) propose to define the relation between a human being and his role(s) in terms of an agency relationship. This concept, which derives from research in economics, can explain the non-alignment of individual and institutional goals; it allows for the consideration of the individual’s whole set of goals and desires (see Eisenhardt 1989 for an introduction; for some specific applications to argumentation, see Goodwin 2010).

According to Rigotti and Rocci (ibid., pp. 174-175), individuals are interconnected by two types of relations which complement their institutional engagements in roles and communicative flows. The former relation concerns interpersonal relationships between the individuals, while the latter concerns the link of individuals to the community, i.e. their cultural identities. Both types of relation are to be taken into account in mediation. At the interpersonal level, the individuals’ stories as well as their representations of their relationship are to be taken into account. For example, when mediators enter a conflict, they have to be aware and respectful of many delicate facets of interpersonal rapports – think, for instance, about a family conflict, or to a conflict in a classroom. Moreover, the cultural context, including the individuals’ common identities, experiences and stories also influences the possible proceeding of mediation. In view of these considerations, the interpersonal dimension is certainly to be included in the definition of a notion of context viable for the study of contextualised argumentation.

3.2. Reconstructing the features of the specific context taken into account in the argumentative analysis

The analysis of the notion of context is certainly not sufficient. Scholars who deal with argumentation in context must take into account the specific features defining the considered context, namely the precise activity type that is relevant to a given argumentative analysis. In fact, in order to understand what specific constraints and opportunities are available to the arguer, it is necessary to take into account the specific context of argumentation (van Eemeren 2010).

In this relation a methodological premise is necessary, for which I am indebted to Marcelo Dascal[ii]. This author observes that, context is, per se, an infinite concept, and you cannot tell what is relevant to the interpretation of a certain communicative action in advance. Contextual details that are prima facie irrelevant to the context of a certain communicative interaction can turn out to be fundamental to explain some aspects of this latter. Contrarily, in some cases, very clear and prominent aspects of a certain institutional context may be unimportant for the interpretation of a communicative interaction taking place within it – because, as said above, the arguers’ freedom always exceeds the constraints of the expected activity types. Methodologically speaking, thus, the interpretation of any text and the choice of what its relevant context is should be certainly done by starting from the text itself.

I would like to add, however, that in the case of contexts that are to some extent institutionalised, such as the legal context, the financial context, and also practices such as teaching, doctor-patient consultation, dispute mediation and many others, starting a textual analysis without first having a clear picture of the main characteristics of the concerned context or practice would be unwise. To quote a very blunt example, knowing that mediators are expected to be neutral third parties is important to understand their somewhat reluctant behaviour during the argumentative discussion (see the definition of the mediator’s role in van Eemeren et al. 1993 and Jacobs 2002). The same behaviour would seem incomprehensibly reticent to an analyst who were not familiar with this context. Even more clearly, in order to study argumentation in takeover proposals in the financial market, one must have a clear picture of what a takeover proposal is, which steps this process requires; and one must first acknowledge the surprisingly high number of communicative and argumentative activities embedded in this type of financial operation (Palmieri, this volume). It would be very difficult even to find out argumentation without a previous picture of the takeover proposal as a type of communication context.

Having clarified this methodological premise, it is now important to specify why understanding the specific features of a certain context is crucial for argumentation. In general, as van Eemeren and Grootendorst (2004) put it, specific knowledge of the context where the argumentative interaction takes place is relevant to the analytical reconstruction of argumentation, achieved thanks to an analytic overview of the critical discussion, which helps bring to light “which points are at dispute, which parties are involved in the difference of opinion, what their procedural and material premises are, which argumentation is put forward by each of the parties, how their discourses are organised, and how each individual argument is connected with the standpoint that it is supposed to justify or refute” (ibid., p. 118). Context is relevant to the production of an analytic overview because it often sets up expectations and conventions which may justify a specific reconstruction. Knowledge of the specific context, thus, in terms of institutionalised and interpersonal relations, becomes a source for an accurate analytical reconstruction and also, we could add, for the evaluation of the argumentative discourse (Arcidiacono et al. 2009).

More specifically, numerous important relations between an accurate reconstruction of context and the argumentative analysis may be listed. Here, I would like to stress three fundamental aspects in particular.

First, it is necessary to consider context in order to provide a reliable interpretation of texts; context helps disambiguate terms and expressions and understand their meaning (Dascal 2003, 11ff). Frequently, knowledge of context is extremely relevant to understand whether a given utterance is part of an argumentative discussion or not (Arcidiacono et al. 2009).

Second, analysts have to consider the context of an argumentative discussion if they want to evaluate whether the selection (or, respectively, the exclusion) of the debatable issues operated by the participants to the argumentative discussion is sound or not. It is clear that not every issue is appropriate to every context. Limitations can be due to constraints based either on the institutionalised or on the interpersonal dimension of context. In order to illustrate how the institutionalised dimension of context may impose constraints on the choice of issues, I will present an example from the process of dispute mediation. At the beginning of the process, the mediator looks for the roots of the parties’ disagreement. He then guides the disputants in the exploration of their points of disagreement and differences of opinion that have made the conflict develop (Greco Morasso 2008). However, once identified these issues on which originally the disagreement was placed – for example, an unbalanced workload on one of two business partners; or a misunderstanding in the interpretation of an adoption agreement – the mediator does not allow the parties to continue discussing their responsibilities and faults. Assessing the individuals’ responsibilities, in fact, would be a typical issue for a court trial, but it is not appropriate in a mediation process. Similarly, there is no room in mediation for the reconstruction of the deep conscious and unconscious motivations of the parties’ actions – that would be an issue for a therapist, not for a mediator (Greco Morasso 2011).

So, after having brought the original issue of disagreement to the surface, what the mediator does is to shift the discussion from the disagreement to the possible options for its resolution. Possible conflict resolution options are typical issues admitted in the process of mediation, which is institutionally oriented to the resolution of the parties’ conflict. Greco Morasso (2011) analyses a conflict in a university context originated from a harassment complaint advanced by a student against her professor and mentor. Now, provided that the episode originating this complaint was more a misunderstanding than a serious offence, the reasons of that misunderstanding and the parties’ respective faults are not investigated during the mediation process. The mediator invites the parties to discuss about how they can continue their academic relationship in the future without being the victims of further misunderstandings. This is a typical constraint on the choice of debatable issues that is due to the institutionalised dimension of conflict and, more precisely, to the interaction scheme of mediation.

Constraints over the choice of issues can derive from the interpersonal dimension too. A family, for example, may allow more or less room to the argumentative discussion; some issues may be unquestionable (Arcidiacono et al. 2009). Other forms of interpersonal relationships, like the relation between friends, or a religious community, may equally allow more or less freedom to discuss or limit the issues that can be debated.

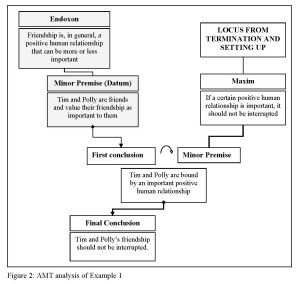

A third point has been recently highlighted, in particular, in the research stream bound to the Argumentum Model of Topics (henceforth: AMT, see Rigotti 2006, 2009; Rigotti and Greco Morasso 2010). There is an inherently contextual dimension of arguments; thus, scholars studying argumentation in context must carefully consider how the general contextual framework of an argumentative discussion affects the actual argumentative moves put forward by the co-arguers. In particular, a method which has proven proficuous is to work at the level of reconstruction of explicit and implicit premises of single argumentative moves and see how much of these premises depend on context.

According to the AMT perspective, roughly speaking, each argument is based on an argument scheme in which one component is based on an abstract inferential connection (maxim), while another component is anchored in the material dimension of context, culture, etc (Rigotti and Greco Morasso 2010). Context, thus, is not just the blurred sphere in which argumentation is taking place. It has an effect on the premises of specific argumentative moves.

In dispute mediation, for example, context-bound premises like “we are friends”, “our business has a good bottom line” or “we want to continue our relationship” are very common in arguments that the parties advance about the opportunity to settle their conflict. The following example, taken from Greco Morasso (2011) and analysed below according to the AMT, shows how these contextual premises are part of the argument itself. Let us introduce the example first. It is a part of a mediation session in the context of a business relation in which a problem is occurred. In this case, as it emerges precisely in the following passage (Example 1), the business partners are friends:

The analysis of this extract according to the AMT is proposed in Figure 2. I shall not go into great detail in the discussion of the AMT now (see Rigotti and Greco Morasso 2009 for a detailed presentation of the model). I shall rather focus on how the context affects the actual argumentation.

If we look at the premises on the left, represented in the grey textboxes (Endoxon and Datum), their contextual nature is quite evident. The endoxon represents a general assumption about the value of friendship, which is largely accepted, but still is cultural in nature (we could imagine cultural contexts in which such an assumption would have less hold). The Datum concerns some factual information about Tim and Polly’s friendship: they value their friendship as important, at least to a certain extent, as it emerges from the discussion reported in Example (1). This is something bound to the close actual context of the parties’ interpersonal relationship.

Taken together, Endoxon and Datum show how much the context of the parties’ institutionalised and interpersonal relationship is relevant to arrive to the conclusion that it is worth solving the conflict. Indirectly, they also prove how much context affects the single argumentations put forward during an argumentative discussion. Knowing the context, thus, is necessary even to reconstruct the inner structure of the arguments advanced during the argumentative discussion. Conversely, distinguishing premises which are drawn from context is a challenge to be met in order to give a full account of how a specific communication context affects actual argumentative moves.

3.3. Being open to interdisciplinarity

In research truly focused on argumentation in context, the reconstruction of the specific features of the considered context calls for interdisciplinary integrations. Interdisciplinarity is required in order to grasp the complexity of the considered context and to arrive to a reliable analytical reconstruction of argumentation. To stick to the example of dispute mediation, in order to reconstruct how this practice is structured, it is wise to rely on the different disciplines that have approaches this topic, including conflict resolution and mediation studies (Greco Morasso 2011), and other approaches dealing with conflict (Greco Morasso 2008).

Moreover, even the analysis of single argumentative moves often requires an interdisciplinary attitude. The explicit or implicit premises of contextual nature which emerge as constituents of an argument (see section 3.2) may turn out to be constituted by specialized knowledge (for example scientific knowledge), social representations, values which hold in a given community… In order to be correctly interpreted and to be evaluated against the standard of reasonableness, all these different types of premises challenge analysts of argumentation to acquire a deep understanding of the context they are analysing, possibly including some command of other disciplines beyond argumentation theory.

As a corollary, argumentation scholars could seize the opportunity to produce argumentative analyses whose relevance to the understanding of the different contexts considered can be appreciated by scholars dealing with those contexts from different disciplinary points of view. This type of challenge is important if we want the study of argumentation to become a practice that can have an impact at the level of society.

3.4 Identifying prominent features of argumentation in specific contexts

The fourth challenge which certainly emerged from my analysis of dispute mediation concerns the characterization of argumentation in specific context via the identification of prominent argumentative aspects. As van Eemeren and Houtlosser (2009: 6) remark, although in strategic manoeuvring the three aspects of topical potential, audience demand and presentational devices are connected inextricably, “in argumentative practice the one aspect is often more prominently manifested than another”. Some important methodological advice about the study of argumentation in context can be easily drawn from this consideration. This means that, when dealing with actual (necessarily contextual) argumentative practices, we should look for prominent features of the arguers’ strategic manoeuvring. Such features will contribute to define the role that argumentation plays in each specific context.

Considering dispute mediation, a particularly crucial role of the mediator’s topical potential has emerged in relation to the parties’ change in attitude and learning process that bring them to become co-arguers (Greco Morasso 2011). This is particularly evident in two respects.

First, in the choice of the issues that the parties are allowed to debate. Clearly, parties who enter in mediation have already had previous (generally unfruitful) discussion. What could change this situation is the mediator, who may help them focus on productive issues. As previously mentioned (section 3.2), for example, parties are not allowed to complain about their respective faults; they are expected to devote their attention to the options for the resolution of their conflict.

Second, at the level of argument schemes, the locus from termination and setting up has emerged as frequently employed in dispute mediation and tightly connected with the parties’ decision to solve their conflict by means of mediation. In dispute mediation, the locus from termination and setting up is often applied starting from the premise (maxim, see Rigotti 2006) “if something is a value, it should not be terminated/interrupted”. The use of arguments based on this premise is often solicited or proposed by the mediator. At a closer look, it appears that such reasoning scheme is determinant in a process like that of mediation, because it is strictly bound to its very nature. In fact, the conflict that parties are experiencing, by its very nature, endangers their relationship – be it interpersonal as a friendship, or more institutionalized, as the collaboration in a business corporation – and makes them fear that something they care for can be compromised or lost forever. In this sense, reflecting on the value of a relationship which risks to be jeopardized can be the key to the resolution of the conflict itself. Of course, the premise “if something is a value, it should not be terminated/interrupted” is an abstract principle that, in order to become effective, needs to be applied to some form of relationship or value that is actually worthwhile for the parties. This could be the parties’ friendship, their business relation, their common values and aspirations, their children’s happiness, and so on. During the mediation process, contextual data about what the parties consider worthwhile normally emerge thanks to the mediator’s questioning. These data can then be exploited to construct arguments based on the locus from termination and setting up.

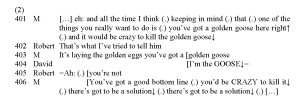

Let us consider a particularly representative example of how the locus from termination and setting up comes into play in mediation. Example (2) is taken from a mediation process between two friends who are the two co-owners of a business corporation with a good bottom line. The excerpt reported here is a recommendation that the mediator makes at the end of the first session:

The mediator not only highlights the value of their business through the image of the golden goose, but he also explicitly says that it would be a pity (literally: it would be crazy) to lose such a value due to the parties’ conflict (see turns 401 and 406). Such argumentation is clearly based on a locus from termination and setting up. The following AMT-based representation (Figure 3) shows that, in this case, the mediator evokes an Endoxon which reminds the parties of the extreme importance of profit in a business context. More, as pointed out explicitly by means of the metaphor of the golden goose, the parties’ business is not just reaching its goal but it is even exceeding the expectations; this confirms and increases the persuasive force of the whole argumentation.

As said above, the locus from termination and setting up is frequently used by the mediator, or it is suggested to the parties as a possible “reasoning path” towards the resolution of their conflict. In a more general perspective, the discovery of such correlation between mediation and locus from termination and setting up may suggest the hypothesis that given loci may be characteristically associated to each communication context. Identifying characterizing loci, thus, would become an important part of the effort to elicit prominent features of the arguers’ strategic manoeuvring in each context. This hypothesis needs, of course, to be verified by empirical studies in different contexts.

4. Conclusion

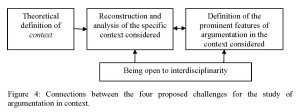

In this paper, I have proposed four challenges for the study of argumentation in context; these challenges open as many paths for further research on how argumentative practices are intrinsically bound to the communication contexts in which they occur. The relations between these four challenges may be represented as in Figure 4. Arrows indicate that taking a certain challenge into consideration is a necessary prerequisite for accomplishing another challenge; for example, being open to interdisciplinarity is necessary in order to reconstruct the specific context considered and to fully understand the prominent features of argumentation in the context considered; the two latter challenges are interdependent, and so on.

The choice of these specific four challenges is the result of what emerged from my personal research experience on argumentation in the context of dispute mediation. I am aware that the list is not exhaustive and that it should be discussed, amended and further enlarged. This can be only done through the dialogue between theoretical and empirical approaches to argumentation in context and through confrontation with other studies on argumentation in different contexts.

NOTES

[i] Van Eemeren (2010) emphasises the dependence of communicative activity types on specific cultural and institutional circumstances. As examples of communicative activity types, he proposes, for example, the British Prime Minister’s Question Time or the presidential debate in the US. Following Rigotti and Rocci, I propose to further split the notion of activity type by considering that, in a communicative activity type like “business mediation” (as it is understood for example in North America) we still have to distinguish some features that are due to the interaction scheme of mediation, and which would be the same also in family mediation, environmental mediation, and so on; and some institutional features which are due to the interaction field of business and which we would not find in a family, in a school or in another interaction field. I believe that the distinction between genres of communicative activity and communicative activity types introduced by van Eemeren (2010) elaborates on a more abstract level of categorization and it does not overlap with the specification of the notion of activity type into interaction scheme and interaction field.

[ii] Marcelo Dascal discussed this topic during a PhD course named “From difference of opinion to conflict” held in Lugano on February 15-17, 2010, in the framework of the doctoral program Argupolis.

REFERENCES

Aakhus, M. (2003). Neither naïve nor critical reconstruction: dispute mediators, impasse, and the design of argumentation. Argumentation, 17(3), 265-290.

Arcidiacono, F., Pontecorvo, C., & Greco Morasso, S. (2009). Family conversations: the relevance of context in evaluating argumentation. Studies in Communication Sciences, 9(2), 79-92.

Dascal, M. (2003). Pragmatics and communicative intentions. In M. Dascal, Interpretation and Understanding (pp. 3-30). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Eemeren F.H. van, et al. (2009). Argupolis: A doctoral program on argumentation practices in different communication contexts. Studies in Communication sciences, 9(1), 289-301.

Eemeren, F.H, van (2010). Strategic manoeuvring in argumentative discourse. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Eemeren, F.H. van, & Houtlosser, P. (2009). Seizing the occasion: parameters for analysing ways of strategic manoeuvring. In F.H. van Eemeren and B. Garssen (Eds.), Pondering on problems of argumentation: Twenty essays on theoretical issues (pp. 3-14). New York: Springer.

Eemeren, F. H. van, & Grootendorst, R. (2004). A systematic theory of argumentation: The pragma-dialectical account. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Eemeren, F.H. van, & Houtlosser, P. (2005). Theoretical construction and argumentative reality: An analytic model of critical discussion and conventionalised types of argumentative activity. In D. Hitchcock and D. Farr (Eds.), The Uses of Argument. Proceedings of a Conference at McMaster University, 18-21 May 2005 (pp. 75-84). Hamilton: Ontario Society for the Study of Argumentation.

Eisenhardt, K. (1989). Agency theory: An assessment and review. The Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 57-74.

Goodwin, J. (2010). Trust in experts as a principal-agent problem. In C. Reed & C. W. tindale (Eds.), Dialectics, dialogue and argumentation: An examination of Douglas Walton’s theories of reasoning and argument (pp. 133-143). London: College Publications.

Greco Morasso, S. (2008). The ontology of conflict. Pragmatics & Cognition, 16(3), 540-567.

Greco Morasso, S. (2011). Argumentation in dispute mediation: a reasonable way to handle conflict. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Jacobs, S. (2002). Maintaining neutrality in dispute mediation: managing disagreement while managing not to disagree. Journal of Pragmatics, 34(10-11), 1402-1426.

Jacobs, S., & Aakhus, M. (2002a). How to resolve a conflict: two models of dispute resolution. In F. H. van Eemeren (Ed.), Advances in pragma-dialectics (pp. 29-44). Amsterdam: Sic Sat/ Newport News: Vale Press.

―. (2002b). What mediators do with words: implementing three models of rational discussion in dispute mediation. Conflict resolution quarterly, 20(2), 177-203.

Muller Mirza, N., & Perret-Clermont, A.-N. (2009). Argumentation and education. Theoretical foundations and practices. New York: Springer.

Palmieri, R. (2010). Argumentative strategies in takeover proposals. This volume.

Rigotti, E. (2006). Relevance of context-bound loci to topical potential in the argumentation stage. Argumentation, 20(4), 519-540.

―. (2009). Whether and how classical topics can be revived in the contemporary theory of argumentation. In F. H. van Eemeren and B. Garssen (Eds.), Pondering on problems of argumentation: Twenty essays on theoretical issues (pp. 57-178). New York: Springer.

Rigotti, E., & Greco Morasso, S. (2009). Argumentation as an object of interest and as a social and cultural resource. In N. Muller Mirza and A.-N. Perret-Clermont (Eds.), Argumentation and education: Theoretical foundations and practices (pp. 9-66). New York: Springer.

Rigotti, E., & Greco Morasso, S. (2010). Comparing the Argumentum Model of Topics to other contemporary approaches to argument schemes: the procedural and material components. Argumentation, 24(4), 489-512.

Rigotti, E., & Rocci, A. (2006). Towards a definition of communication context. Foundations of an interdisciplinary approach to communication. Studies in Communication Sciences, 6(2), 155-180.

Walton, D. N., & Lodder, A. R. (2005). What role can rational argument play in ADR and Online Dispute Resolution? In J. Zeleznikow and A. R. Lodder (Eds.), Second international ODR Workshop (odrworkshop.info) (pp. 69-76). Tilburg: Wolf Legal Publishers.

Walton, D. N., & Godden, D. M. 2006. Persuasion dialogue in online dispute resolution. Artificial Intelligence and Law, 13(2), 273-95.