1. Introduction

1. Introduction

Pragmatic argumentation – also referred to as ‘instrumental argumentation,’ ‘means-end argumentation,’ ‘argumentation from consequences’– is generally defined as argumentation that seeks to support a recommendation (not) to carry out an action by highlighting its (un)desirable consequences (see, e.g., Perelman & Olbrechts-Tyteca 1969; Schellens 1987; van Eemeren & Grootendorst 1992; Walton, Reed & Macagno, 2008). Pragmatic arguments are fairly common in everyday discourse and particularly in discussions over public policy. Cases can be identified in the print media on a regular basis. For example, by the end of June 2010, the U.K.’s Chancellor George Osborne was defending the Lib-Con budget as a means to “boost confidence in the economy” (“Budget: Osborne Defends ‘Decisive’ Plan on Tax and Cuts”, 2010); Israel’s defence minister, Edhud Barak, was attacking the timing of plans to demolish 22 Palestinians homes in East Jerusalem as being “prejudicial to hopes for continuing peace talks” (“Ehud Barak Attacks Timing of Plans to Demolish 22 Palestinian Homes”, 2010); and major oil companies were attacking the US government’s ban on deepwater drilling as a policy that was “destroying an entire ecosystem of businesses” and “resulting in tens of thousands of job losses” (“US Gulf Oil Drilling Ban Is Destroying ‘Ecosystem of Businesses’”, 2010).

In this paper I propose an instrument to evaluate pragmatic argumentation. My theoretical framework is the pragma-dialectical theory of argumentation. Instruments to analyse and evaluate pragmatic arguments have already been proposed in pragma-dialectics. These instruments consist of an argument scheme and a set of critical questions. The argument scheme represents the inference rule underlying the argumentation and the critical questions point to the conditions a pragmatic argument should fulfil for that inference rule to be correctly applied. I consider these proposals extremely useful – as it happens, the evaluative instrument I set out in the following sections relies heavily on the existing instruments. This said, there is significant room for improvement and that’s why this paper seemed necessary. Specifically, I am inclined to formulate the argument scheme somewhat differently and to reorganise, reformulate, and complement the list of critical questions. When designing the critical questions I have drawn occasionally on the work of Clarke (1985), Schellens (1987), and Walton (2007) who have also studied pragmatic argumentation from a dialectical perspective. Even though Clarke and Walton deal with ‘practical inferences’ and ‘practical reasoning’ respectively, from the definitions they propose, it is clear that these labels refer fundamentally to the same argumentative phenomenon defined above as ‘pragmatic argumentation.’

Due to the limited scope of this paper, I will not start, as is customary, with a review of the pragma-dialectical literature on the pragmatic argument scheme and critical questions, but restrict myself instead to the presentation and justification of a reformulated version of the aforementioned instruments.[i]

2. The evaluation of argumentation in pragma-dialectics

Before putting forward my proposal, I shall make explicit my theoretical starting points. In pragma-dialectics the evaluation of argumentation (with an unexpressed premise) proceeds in two stages (van Eemeren & Grootendorst 2004, pp.144-151). The first stage is to examine whether the parties agree that the material premise of the argumentation is part of the shared material starting points of the discussion.[ii] The procedure by which the parties determine this is referred to as the inter-subjective identification procedure (IIP). If this procedure yields a negative outcome the argument used by the protagonist is then deemed ‘fallacious’ and the evaluation of the argument comes to an end. If the result is positive, the analyst must turn to the next evaluative stage to determine if the parties agree that the argument scheme used is a shared procedural starting point. If the protagonist has made used of an argument scheme that is not part of their agreements the argumentation is fallacious. This is the second point at which the evaluation may come to an end. In contrast, the evaluation must continue if the parties agree that the scheme is a shared procedural starting point. The reason for this is that, by agreeing on the legitimacy of the scheme, the protagonist is conferred the right to employ a specific type of inference rule to transfer the acceptability of the material premise to the conclusion. However, since this inference rule can be instantiated in infinite ways and not all of these substitution instances will actually transfer the acceptability to the conclusion, the analyst must examine, also, whether the parties agree that the argument scheme has been applied correctly. The procedure by which the parties determine if the argument scheme is appropriate and has been correctly applied is referred to as the inter-subjective testing procedure (ITP).

Critical questions are the dialectical method used by the parties to take a decision concerning the correctness of the application of the scheme (van Eemeren & Grootendorst 2004, p.149). More specifically, critical questions are questions by means of which the antagonist asks the protagonist if there are circumstances in the world – that is, the world as depicted by the material starting points of the discussion – that could hinder the transference of acceptability from the material premise advanced to the conclusion. (Note that this ‘world’ can expand during the discussion, since the list of material starting points can be enlarged throughout the discussion.) If the protagonist wants to maintain his argumentation, he should give as an answer an argument showing that circumstances in the world that could count as ‘obstacles’ are not in place.[iii] These obstacles may fall under two categories: those relating to presuppositions of the standpoint and those linked to the connection premise of the argumentation. I shall give examples for each category in section 3.2.2.

3. Proposals for the evaluation of pragmatic argumentation

3.1. Argument scheme

Having explained the procedures involved in the pragma-dialectical evaluation of arguments, I turn to the characterisation of the pragmatic argument scheme I use as my point of departure:

| Standpoint: |

Action X should (not) be carried out |

|

| Because: |

Action X leads to (un)desirable consequence Y |

(MATERIAL PREMISE) |

| And: |

If action X leads to (un)desirable consequence Y, then action X should (not) be carried out |

(CONNECTION PREMISE) |

Argument schemes specify the type of propositions involved in a type of argumentation and their functions. As detailed in the scheme, the standpoint of pragmatic argumentation is prescriptive. This prescription can aim at creation of either a positive obligation or a negative one (i.e., a prohibition). The material premise of the argument is complex: it can be separated into two propositions, one causal, ‘Action X leads to consequence Y,’ and another evaluative, ‘Consequence Y is (un)desirable.’ As regards the connection premise, ‘If action X leads to (un)desirable consequence Y, then action X should (not) be carried out,’ it is important to realise that it does not commit the arguer to the statement that the conclusion necessarily follows from the material premise but, rather, that the conclusion can follow, in principle, from this premise. It is an inference licence subject to conditions expressed by the critical questions.

3.2 The evaluation procedures

The procedures introduced below are pertinent only to the evaluation of positive variants of pragmatic argumentation, where the recommendation to carry out an action is grounded by mentioning its desirable consequences.

3.2.1 The inter-subjective identification procedure

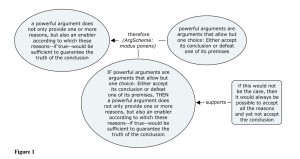

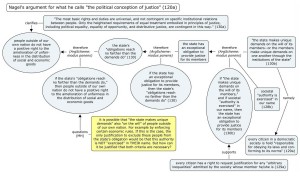

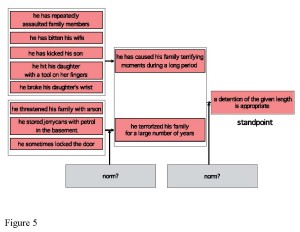

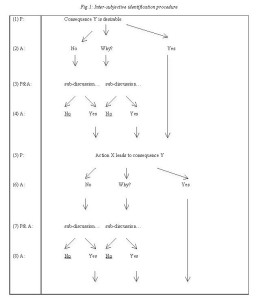

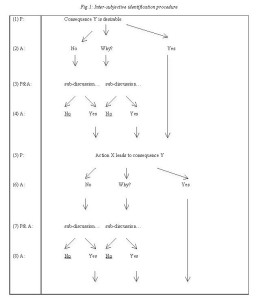

Given that the material premise of pragmatic argumentation involves two propositions, one evaluative and another causal, both need to be checked for their acceptability. The acceptability of the evaluative proposition is checked in turns (1) to (4) of the dialectical profile represented in Fig.1 and the acceptability of the causal premise in turns (5) to (8). Nevertheless, it is also possible for the parties to check the acceptability of the causal proposition first.[iv]

Figure 1

To cut a long story short, I have not represented in the profile each and every option available to the parties at this point of the discussion. The main point I seek to illustrate by means of this profile is that the parties have two opportunities to agree on the acceptability of the evaluative and the causal propositions. For example, the antagonist may immediately concede that the evaluative proposition is part of the material starting points of the discussion. This option is represented in turn (2) by the answer ‘Yes’. It is also dialectically possible for the antagonist to claim that the proposition is not part of their common ground. In that event, the antagonist has two options. One alternative is to simply raise doubts concerning the acceptability of the proposition and subsequently request argumentation from the protagonist to justify its acceptability. This is represented in turn (2) by the question ‘Why?’ A second alterative for the antagonist is to assume an opposite standpoint towards the proposition. This option is represented in the same turn by the answer ‘No’. In both cases, the parties may decide to enter into a sub-discussion to determine the acceptability of the evaluative proposition. If these sub-discussions reach the concluding stage, they will end with either a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answer by the antagonist. If the answer is affirmative, as represented in turn (4), the proposition is acceptable in the second instance.[v] Exactly the same procedure applies to the examination of the causal proposition.[vi]

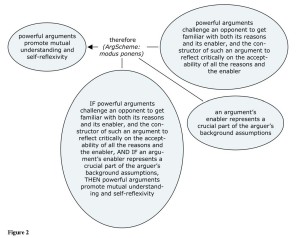

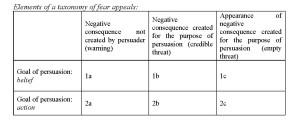

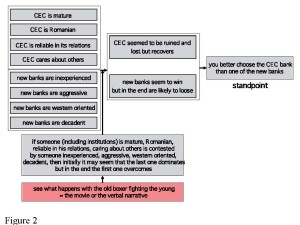

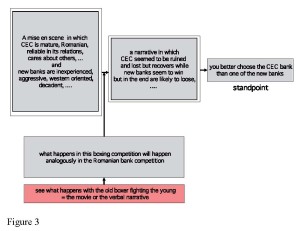

3.2.2. The inter-subjective testing procedure

As explained earlier, the ITP is applied only if the IIP has yielded a positive outcome. Turns (1) and (2) of the profile represented in Fig.2 summarise the first step of the ITP, where the parties check if the pragmatic argument scheme is an acceptable means of defence. The interaction between the parties at this point can become much more complex, but I will stay with this abridged version because my main interest lies on the critical questions. Recall that the point of applying critical questions is to examine whether there are obstacles in the transference of acceptability from the material premise of the argument to the conclusion. This means that the acceptability of the material premise and, thereby, the acceptability of the causal and evaluative propositions, is presupposed by these questions.

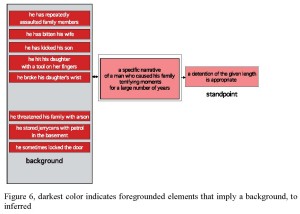

Figure 2

The first critical question relates to a presupposition of the prescriptive standpoint. This presupposition is expressed by the familiar principle ‘ought implies can’ (see, e.g., Kant 1970, A807/B835, A548/B576). In essence, the principle states that the feasibility of an action is a necessary (but not a sufficient) condition to establish an obligation to perform that action. It is also possible to find the inverse version of this principle, which states that the unfeasibility of an action is a sufficient (but not necessary) condition to cancel the obligation to perform that action (see Albert 1985, p.98). Hence, a pragmatic argument will fail to provide support to its standpoint if the action recommended cannot be carried out. Clarke (1985), Schellens (1987) and Walton (2007) include a critical question inquiring if the recommended action is feasible in their accounts.

An action can be ‘unfeasible’ because it is ‘unworkable’ or ‘non-permissible.’ Schellens (1987) acknowledges these two senses of feasibility when he introduces two questions relating to the contextual limitations for carrying out an action: ‘Is action X practical?’ and ‘Is action X allowable?’ By the term ‘unworkable action’ I mean an action that is incompatible with factual limitations, and by a ‘non-permissible action’ one that is incompatible with institutional or moral principles, norms, or rules. For example, the policy of rising education spending could be ‘unworkable’ if there is a budget deficit. Similarly, the development of nuclear power as a method of energy production could be unworkable if there is no capacity to forge single-piece reactor pressure vessels, which are necessary in most reactor designs. In contrast, the measures of an immigration bill could be unfeasible, in the sense of ‘non-permissible,’ if they were incompatible, for example, with the European Convention of Human Rights. Note that an important corollary of including the notion of permissibility under the concept of feasibility is that a pragmatic argument can be defeated by a rule or principle. The latter, however, only insofar as the principle or rule is part of the shared starting points of the discussion and if the parties agree, also, that such principle or rule should take precedence over the desirable consequences brought about by the action.[vii]

As illustrated in the profile, when the protagonist is faced with a critical question concerning feasibility, he has two options. One is to acknowledge that the action is unfeasible and retract his argumentation. This is represented by the answer ‘No’ in the profile. The second alternative is to maintain his argumentation and provide further argumentation. This choice is represented by the answer ‘Yes’. His argumentation may show that the action is feasible or, alternatively, that the action will become feasible if some changes are introduced in the status quo – changes which, in turn, he should prove viable.[viii]

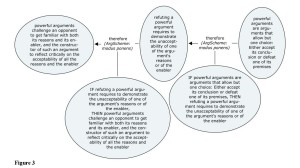

Necessary-means question

Once the parties have agreed that the action is feasible they should turn to critical question (2a), ‘Could the mentioned result be achieved by other means as well?’ Note that the question does not ask whether the action will indeed lead to the mentioned effect. The question presupposes a positive answer to the latter and inquires, instead, whether the action is a necessary cause. To prove that the mentioned cause is necessary the protagonist needs to show that unless the action is performed the desirable state of affairs will not take place.

How can the protagonist prove the cause ‘necessary’? It seems there are two ways of establishing this claim. One is to show that some presumed alternative means X’ does not actually lead to desirable effect Y. Another way would be to indicate that alternative action X’ cannot be carried out. Any of these responses would allow the protagonist to maintain, for the time being, his argument and standpoint. This move is represented by the answer ‘No’ in the profile.[ix] As a case in point, consider the argument: ‘The UN Security Council should send Iran a package of positive incentives (e.g. selling Iran light water nuclear technology, civilian aircraft, etc.) to encourage the halt of its uranium enrichment program.’ Suppose that the antagonist puts forward an objection of this sort: ‘However, the same effect could be achieved if the UN, instead of sending positive incentives to Iran, decided to apply economical sanctions to Iran, such as requesting Iran’s most important trading partners (e.g. China, Japan and India) to cut back on their imports of Iranian crude oil. In response to this objection, the protagonist could attack the causal relation of the antagonist’s argumentation. He could claim, for example, that economical sanctions by the UN Security Council would prove futile given Iran’s growing expansion of economic and political ties with countries such as Turkmenistan, Venezuela, Kuwait and Malaysia. Alternatively, he could point out that the UN cannot impose economical sanctions on Iran because, for instance, two important council members, China and Russia, disapprove of such measure.

Best-means question

Next, consider a situation where the answer to critical question (2a) is ‘Yes’, that is, if the action proposed is not a necessary cause. On the surface, it appears that if action X is not necessary because there is another means X’ to achieve exactly the same effect Y, there is no obligation to carry out action X. From this it seems to follow that a positive answer to this question would, if not defeat, at least weaken the pragmatic argument of the standpoint.

On closer inspection, however, it is possible to identify cases where pragmatic argumentation can be reasonable even if it mentions an action that is not a necessary cause. As an illustration, consider the following pragmatic argument: ‘In order to mitigate greenhouse gas emission we should invest in building more concentrated solar energy plants (CSP).’ If an arguer, in his role as antagonist were to ask ‘Are there other ways, besides building CSP, to mitigate greenhouse emissions?,’ the answer (in our world) would be an emphatic ‘Yes’ – it is clear that there are alternative ways. One of them has been at the centre of much talk on global warming: the development of nuclear power as a method of energy production. The crucial difference with the example about Iran and its enrichment uranium program is that, in the CSP case, nuclear power does emit relatively low amounts of carbon dioxide, leading therefore to the desired effect of mitigating greenhouse emissions. Moreover, it is feasible in several countries since the technology is readily available. In other words, the alternative means is indeed a ‘means’ to the desired effect and it is feasible. Building CSP is therefore not really necessary to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions. However, should one conclude from this that the argument is a bad argument? Not necessarily. The protagonist can maintain his argumentation so long as he shows that this action is the best among other alternative means to achieve the desired effect. In this specific example, he could argue that, on balance, that is, considering the advantages and disadvantages of building CSP, on the one hand, and of developing nuclear power, on the other, the former is a better alternative than the latter. He could point out, for instance, that the problem of radioactive waste is still unsolved and that there are high risks related to the production of nuclear energy. For the reasons adduced above, an affirmative answer does not necessarily undermine the argumentation, but rather leads to another critical question, represented in turn (7): ‘‘Is the mentioned cause, on balance, the best means to achieve the desirable effect?’[x]

In his study, Clarke (1985) distinguishes a “basic” and “option” pattern of practical inferences. The basic pattern entertains a single action as a means of what is wanted. In the option pattern, the agent must choose between a number of alternative means rather than decide on a single action (p. 22). In a similar vein, Walton (2007) formulates two schemes for practical reasoning, one referring to a ‘single action’ and another that accounts for ‘a situation with alternative means’ (p. 202). In this way, Clarke and Walton acknowledge that the action recommended by a pragmatic argument can be intended sometimes as the one to be preferred among several options rather than as the only means available to achieve some desirable end. Both authors, however, seem to treat the requirements that the action proposed should be a necessary cause and that this should be the best means as perfectly compatible. In fact, Clarke argues that all positive variants of practical inferences should mention a necessary cause (1985, pp. 22-23) and Walton proposes a ‘necessary condition scheme’ for a situation with ‘alterative means’ (2007, p. 204). I disagree with them in this last respect. These requirements are mutually exclusive: an action that is claimed to be the best among alternative means to achieve some desirable effect cannot be claimed to be, at the same time, a necessary means to achieve that effect. In addition, it seems that in evaluating pragmatic arguments, the analyst should start by asking whether the cause is a necessary cause and, only if the answer is negative, ask if the cause is the best means to realise the desired effect.

Certainly, in determining whether an action is the best means to achieve or avoid some state of affairs the parties will have to deal not only with issues concerning causality but also desirability. In particular, they will have to weigh up the costs and the additional advantages of the proposed action and the alternatives means.

Side-effect questions

Let us assume now that the parties have agreed that the mentioned cause is a necessary cause, as indicated in turn (6). The next question that needs to be considered is question (3a), namely, whether there are any cost effects to the proposed action. If the parties agree that there are no cost-effects, then the protagonist has successfully defended his standpoint.

The above does not mean, however, that a ‘Yes’ answer will automatically defeat the protagonist’s argumentation. His argumentation still has a chance of success. Take the events that took place in Greece some months ago. Prime Minister Papandreou proposed a series of austerity measures to address the country’s financial crisis. In defending the government’s case, the PM argued that the measures were necessary to borrow money from the international market and that this was in turn necessary for the country to avoid bankruptcy. Suppose, for the sake of the argument, that the only means of borrowing money from the international market was to implement the hefty cuts and reforms included in the government’s proposal. Faced with the question ‘Does the mentioned cause have undesirable side-effects?’ the PM would have answered most certainly ‘yes’: in fact, he admitted that the planned changes were “painful” and referred to them in terms of “sacrifices” required to put the country’s finances in order (“PM Sets Scene for ‘Painful’ Measures”, 2010). Does this make the Greek government’s argument for the approval of the measures a weak argument? Not necessarily: Not if the benefits resulting from those measures – borrowing the money and thereby remedying Greece’s fiscal situation – outweigh the costs brought about by those measures.[xi] This possibility is accounted for by critical question 3b, ‘Does the desirable effect mentioned in the argumentation (and any additional advantages of the mentioned cause) outweigh its undesirable side effects?’[xii]

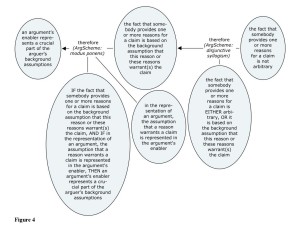

4. Conclusions

In the preceding sections I have outlined an instrument to evaluate pragmatic arguments from a pragma-dialectical perspective. This instrument consists of a dialectical procedure to establish the acceptability of the argumentation (the IIP) and another one to examine its justificatory function (the ITP).

Concerning the first of these procedure, I have stressed that both causal and evaluative propositions involved in the material premise ought to be checked for their acceptability. This point is worth emphasising since the evaluative proposition of pragmatic argumentation is often left implicit in practice.

As regards the justificatory function of pragmatic argumentation I have provided a rationale for each critical question. Furthermore, I have situated these questions in a dialectical profile to make clear that certain critical questions have priority over others – that is to say, that there are certain questions whose inappropriate response makes the subsequent questions in the list unnecessary. For example, if the action proposed is unfeasible the reaming questions become irrelevant. The profile also shows that sometimes there is more than one reasonable type of response to a critical question. Thus, according to the procedure outlined, a pragmatic argument is reasonable if (1) the proposed cause is the best means among several options to achieve some desired effect, (2) if it is a necessary means with no cost effects, or (3) if it is a necessary means with cost effects, but the desirable effects outweigh the former.[xiii]

NOTES

[i] Pragmatic argumentation is described in van Eemeren, Grootendorst & Kruiger 1983; van Eemeren & Grootendorst 1992, p. 97, 162; Garssen 1997, p.21; van Eemeren, Grootendorst & Snoeck Henkemans 2002, pp.101-102. The argument scheme is outlined in Feteris 2002, p.355 and also, with some modifications, in van Eemeren, Houtlosser & Snoeck Henkemans 2007, p.170. The critical questions for pragmatic argumentation are listed in Garssen 1997, p.21 (available only in Dutch). An English translation of these questions can be found in van Eemeren, Houtlosser & Snoeck Henkemans 2007, p.170.

[ii] This description of the evaluative process is premised on an immanent view of dialectics. According to this perspective, the analyst should examine the acceptability of the argumentation solely in consideration of the material starting points of the discussants (see Hamblin 1970). Nevertheless, it is also possible to conceive the evaluative process from a non-immanent perspective and assign the analyst a more active role in the evaluation. In the latter case, if the analyst considers that the material premise of the argumentation is unacceptable when both parties have recognised it as a shred material starting point, the analyst may start a discussion with the parties concerning the acceptability of that proposition. In this discussion, the analyst not only questions the acceptability of the argumentation but also assumes the opposite point of view than the parties. Being protagonist of his own standpoint, he should put forward argumentation to justify his position.

The description also assumes that there are two real parties to the discussion. The same alternatives – and immanent versus a non-immanent view of dialectics – apply even if the antagonist is only ‘projected’ by the protagonist. In both cases the analyst should try to ‘reconstruct’ the projected antagonist. In the first case, the analyst will judge the acceptability of the argumentation in view of the presumably shared starting points by protagonist and antagonist; in the second case, he will take a more active role in the evaluation, making explicit his disagreement concerning the acceptability of the argumentation.

[iii] In the ideal model of a critical discussion, where every argumentative move is made explicitly, the parties expressly agree on the critical questions at the opening stage. This agreement is reached more or less simultaneously to the agreement that a certain type of argument scheme will count in the present discussion as an acceptable means of defence. By contrast, discussants rarely agree explicitly in practice on the critical questions relevant to a type of argument scheme. This puts the burden on argumentation theorists to propose critical questions for conventionalised types of argument schemes such as the pragmatic argument scheme. In designing these questions, they look for the kind of evidence that could count against a specific type of argumentation starting from the assumption that the material premise is acceptable.

[iv] From an evaluative perspective, the acceptability of the causal proposition is just as significant as that of the evaluative proposition. For this reason, the order followed by the parties when checking the acceptability of the material premise in the IIP is irrelevant. This is not to say, however, that the order is irrelevant from the point of view of the production of a pragmatic argument: means cannot be defined without having established the goal to be achieved first.

[v] It is worth noting that the desirability of an effect is always a matter of degree. We judge the desirability of a state of affairs not only against some shared standard but also in relation to the desirability of other possible state of affairs. For example, we might consider that diminishing the rate of unemployment by 2% is desirable but diminishing it by 4% is even more desirable. Judging the 2% against the 4%, the 2% is less desirable, but at the same time, it is not undesirable when judged against a 0% reduction. Because desirability is a matter of degree, the ‘Yes’ and ‘No’ answers in the dialectical profile should not be understood in absolute but rather relative terms. I fact, the antagonist may dispute the desirability of Y not only by assuming the opposite standpoint ‘Y is undesirable’, but also by assuming two related standpoints of the form ‘Y is less desirable than Z’ and ‘We should pursue Z instead’. Proving the acceptability of the second standpoint is necessary because Z might be more desirable than Y but Z might be nonetheless unattainable under the current circumstances. If that is the case, then the acceptability of the evaluative premise ‘Y is desirable’ has not been attacked successfully. I am grateful to one of my commentators for drawing my attention to this point.

[vi] The causal proposition can be justified in several ways. It can be grounded, for instance, by an argument from authority (e.g., ‘According to a recent research in the U.S., wide availability of firearms results in more violence and homicides’). It can be justified as well by an argument from analogy (e.g., ‘Policies reducing access to firearms in the UK have resulted in less homicides and violence. We should apply the same policy in U.S.’). Also, the causal proposition can be supported by a symptomatic argument, where the specific causal relation in the causal premise of a pragmatic argument is justified by referring to a causal generalisation (e.g., The conflict between Israel and Palestine ought to be solved by peaceful means. I don’t believe in the concept of a ‘just war’.)

[vii] In this way, the procedure leaves up to the parties the decision to follow a teleological or a deontological conception of ‘reasonable actions’, when there is a clash between desirable consequences and moral principles.

[viii] Once the protagonist has advanced argumentation to meet a critical question, the antagonist may regard this argumentation unconvincing. In that event, the parties may decide to go into a sub-discussion. To keep the profile simple, I have not represented these sub-discussions. It is important to bear in mind, though, that this is a dialectical – and, therefore, reasonable – possibility.

[ix] This critical question does not ask from the protagonist to refute the existence or the feasibility of ANY possible alternative means. Dialectically speaking, the protagonist has the obligation to show that the action cannot be achieved by other means only if the antagonist has proposed alternative means to achieve the desirable effect. If the antagonist does not come up with any alternative means, then the action can be considered – for the time being, that is, within the present critical discussion – necessary.

The burden of proof of the protagonist in this respect becomes clearer when his argumentation is judged within the context of an activity type. As an illustration, consider the context of parliamentary debates, where pragmatic arguments are quite common. In this activity type the measures of a bill will be ‘necessary’ for the achievement of some desirable aim if (for the time being) the opposition has not come up with alternative measures, or if the measures proposed by the opposition do not really lead to the desired effect or are unfeasible. Moreover, because parliamentary debates are discussions not only among MPs but also – and, probably, mainly – between MPs and the public, the protagonist of a pragmatic argument should also take into consideration the alternatives being debated in the broader public sphere (i.e. in the media).

[x] Walton (2007) acknowledges that we do not always need to argue from necessary causes in practical reasoning. In his view, it is sometimes perfectly reasonable to argue from sufficient cause.

He illustrates this with the following example: ‘My goal is to kill this mosquito. Swatting the mosquito is a sufficient means of killing the mosquito. Therefore, I should swat the mosquito.’ I certainly concur with Walton that this argument seems perfectly reasonable, even though swatting the mosquito is not a necessary condition for killing it (there are many other more creative ways of doing this). However, I don’t think one can conclude from this that it is permissible to argue from sufficient causes in pragmatic argumentation. The cause is not necessary because there are other available means of killing the mosquito. That being the case, one should still ask in principle if swatting it is the best means on balance. Of course, in this case, the side effects and additional advantages of each of the means available are probably almost equivalent (or, to some, irrelevant), so that in the end, it does not really make so much of a difference which of the means is chosen.

[xi] It is interesting to observe how politicians strategically defend their policies in terms of ‘necessary’ or ‘unavoidable’ means when in fact there are other options available – options which could eventually lead to more advantages and less disadvantages than the policy recommended. This point is nicely made, in my opinion, by David Milliband (UK shadow foreign secretary) in his commentary ‘These cuts are not necessary: they are simply a political choice’, published in response to the 2010 budget introduced by the Lib-Con government. See, The Observer, 27.06.10, p. 19.

[xii] This critical question covers a situation in which both parties agree that X leads to Y and that Y is desirable, but they also agree that there is another desirable outcome Z that is both more desirable than Y and incompatible with Y. In such a situation, the answer to the critical question ‘Does the desirable effect mentioned in the argumentation (Y) outweigh its undesirable side effects?’ should be ‘No’. The response should be negative because: (1) X indirectly precludes – by furthering outcome Y – the achievement of Z and (2), since Z is more desirable than Y, the negative effect of precluding the attainment of Z outweighs the benefit of achieving Y. I am grateful to one of my commentators for drawing my attention to this case.

[xiii] I presented a similar paper earlier and I received a critical comment concerning the different reasonable paths outlined in the profile along the following lines: Suppose the claim at issue is ‘X should be carried out’, and that in one context – let us call it context 1 – X is a necessary cause, with 3 cost effects. Suppose further that the protagonist convinces the antagonist that achieving the desirable effect is so significant that it outweighs those 2 cost effects. In this context, the claim would be justified: X should be carried out. Now imagine some context 2, where not only X but also X’ is a means to achieve the desired effect. Moreover, X has 3 significant cost-effects and X’ has 2. In this case, the conclusion is not that X should be carried out, but rather that X should not be carried out and that Y’ should be carried out instead. How is it possible that the same procedure leads to inconsistent results?

My answer to this objection is as follows: It is true that the parties may reach different conclusions concerning the reasonableness of carrying out an action X according to this procedure. But it is important to keep in mind that the profile does not portray one critical discussion. For each of these options – necessary means versus best means option – the material starting points are different, which means that each option is part of a different critical discussion. In critical discussion 1, there are not other available means and in critical discussion 2 there are available means. So in the second case, X is judged relatively to other options, while in the first case the action is judged only in relation to its claimed advantage(s) and possible disadvantages.

REFERENCES

Albert, H. (1985). Treatise on Critical Reason. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Budget: Osborne defends ‘decisive’ plan on tax and cuts. (2010, June 23). BBC News. Retrieved from: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/10385052

Clarke, D.S., Jr. (1985). Practical Inferences. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Eemeren, F.H. van, Grootendorst, R., & Kruiger, T. (1983). Het analyseren van een betoog. Groningen: Wolters-Noordhoff. Argumentatieleer 1.

Eemeren, F.H. van, & Grootendorst, R. (1992). Argumentation, Communication, and Fallacies. A Pragma-Dialectical Perspective. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Eemeren, F.H. van, Grootendorst, R., & Snoeck Henkemans, A.F. (2002). Argumentation. Analysis, Evaluation, Presentation. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Eemeren, F.H. van, Houtlosser, P., & Snoeck Henkemans, A.F. (2007). Argumentative Indicators in Discourse. A Pragma-Dialectical Study. Dordrecht: Springer.

Ehud Barak attacks timing of plans to demolish 22 Palestinian homes. (2010, June 22). The Guardian. Retrieved from: http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2010/jun/22/barak-attacks-demolition-palestinian-homes

Feteris, E.T. (2002). Pragmatic argumentation in a legal context. In F.H. van Eemeren (Ed.), Advances in Pragma-Dialectics (pp. 223-259). Amsterdam: Sic-Sat.

Garssen, B. (1997). Argumentatieschema’s in pragma-dialectisch perspectief. Een theoretisch en empirisch onderzoek. [Argument schemes in a pragma-dialectical perspective. A theoretical and empirical examination]. With a summary in English. Amsterdam: IFOTT.

Hamblin, C.L. 1970. Fallacies. London: Methuen.

Kant, I. (1970). Immanuel Kant’s Critique of pure reason. (Trans. Norman Kemp Smith). 2nd edition. London: Macmillan.

Milliband, D. These cuts are not necessary: they are simply a political choice, The Observer, 27.06.10, p. 19.

Perelman, Ch., & Olbrechts-Tyteca, L. (1969). The New Rhetoric. A Treatise on Argumentation. Notre Dam: University of Notre Dam Press.

PM sets scene for ‘painful’ measures. (2010, January 30). Kathimerini. Retrieved from: http://www.ekathimerini.com/4dcgi/_w_articles_politics_0_30/01/2010_114496

Schellens, J.P. (1987). Types of argument and the critical reader. In: Argumentation: Analysis and Practice. Proceedings of the Conference on Argumentation 1986 (F.H. van Eemeren, R. Grootendorst, J.A. Blair, Ch.A. Willard, Eds.). Dordrecht-Holland/Providence-U.S.A: Foris publications.

US Gulf oil drilling ban is destroying ‘ecosystem of businesses. (2010, June 21). The Guardian. Retrieved from: http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2010/jun/21/oil-bp-oil-spill

Walton, D. (2007). Evaluating practical reasoning, Synthese, 157, 197 – 240.

Walton, D.N, Reed, Ch, & Macagno, F. (2008). Arguments from Consequences. In Argumentation Schemes (pp. 100ff). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

1. Introduction

1. Introduction