ISSA Proceedings 2010 – Expert Authority And Ad Verecundiam Arguments

While fallacies have been a major focus of the study of arguments since antiquity, scholars in argumentation theory are still struggling for suitable frameworks to approach them. A fundamental problem is that there seems to be no unique category or kind such as ‘fallacy’, and arguments can be seen as fallacious for many various reasons. This heterogeneity does not invalidate the need to study fallacies, but it poses serious difficulties for general systematic approaches. On the other hand, the numerous repeated attempts to find satisfactory perspectives and tools, together with the critical discussions of these attempts, have increasingly contributed to our understanding of the more local situations where different types of fallacies appear, of how and in what circumstances they are fallacious, and, of which contexts and disciplinary areas are relevant to the study of certain types of fallacies.

While fallacies have been a major focus of the study of arguments since antiquity, scholars in argumentation theory are still struggling for suitable frameworks to approach them. A fundamental problem is that there seems to be no unique category or kind such as ‘fallacy’, and arguments can be seen as fallacious for many various reasons. This heterogeneity does not invalidate the need to study fallacies, but it poses serious difficulties for general systematic approaches. On the other hand, the numerous repeated attempts to find satisfactory perspectives and tools, together with the critical discussions of these attempts, have increasingly contributed to our understanding of the more local situations where different types of fallacies appear, of how and in what circumstances they are fallacious, and, of which contexts and disciplinary areas are relevant to the study of certain types of fallacies.

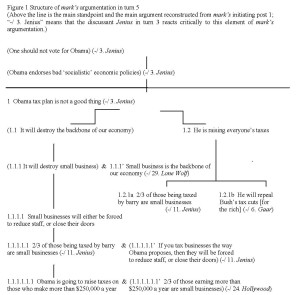

This paper [i] aims to illustrate these issues by selecting one fallacy type as its subject, the argumentum ad verecundiam. The main thesis is that argumentation studies can gain a reasonable profit from consulting a field, the social studies of science, where the problem of appeals to authority has lately become a central issue. The first section summarizes and modestly evaluates some recent approaches to ad verecundiam arguments in argumentation studies. The second section overviews the problem of expert dependence as discussed in social epistemology and science studies. The third section presents a rough empirical survey of expert authority appeals in a context suggested by the previous section. The paper concludes by making some evaluative remarks.

1. The problem of ad verecundiam arguments

An argumentum ad verecundiam can loosely be defined as an inappropriate appeal to authority. As there are different types of authority, ranging from formal situations to informal contexts, the function and success of authority appeals can vary broadly. This paper is concerned with one type of authority, namely cognitive or epistemic authority, i.e. those people who have, or who are attributed by others, an outstanding knowledge and understanding of a certain subject or field – in modern terms, with experts. While not all authorities are experts and, arguably, not all experts are epistemic authorities (as we move from ‘know-that’ to ‘know-how’ types of expert knowledge), the paper is restricted to the problem of epistemic authority appeals, or, in short, appeals to experts.

To problematize the definition of ad verecundiam, let us distinguish between two questions: (1) What does it mean for an appeal to authority to be inappropriate? (2) How do we know if an appeal to authority is inappropriate? From the analytical point of view, the first question is primary since one can identify an ad verecundiam argument only if one knows what it is, and, conversely, once we know how an authority appeal can be inappropriate we are, albeit not necessarily immediately, in the position to distinguish a correct appeal from an incorrect one. However, a more epistemological perspective suggests, as will be illustrated below, that one cannot tell what it means for an appeal to be incorrect before one knows how to find it out, and any specific expansion of the above definition is likely to fail when ignoring the more practical dimension opened by the second question.

In order to spell out this problem in a bit more detail, it is worth considering two recent influential approaches: Douglas Walton’s inferential approach and the functional approach by the pragma-dialectical school. Walton suggests that appeals to authority can be reconstructed according to the following argument scheme (Walton 1997, p. 258):

E is an expert in domain D

E asserts that A is known to be true

A is within D

Therefore, A may plausibly be taken to be true

If appeals to authority are implicit inferences, then the first question (What does it mean for an appeal to authority to be inappropriate?) may be answered by analyzing and evaluating the inference: either the inference form is unsound, or some of the premises fail to be true. The soundness of the argument raises serious problems, for it is obviously not deductively valid, nor can it be classified as an inductive inference in any traditional sense (generalizing or statistical, analogical, causal, etc.), but we can certainly attribute to it a degree of ‘plausibility’ the conclusion claims and put aside further investigations into argument evaluation. What Walton seems to suggest is that it is the failure of the premises that renders the conclusion unacceptable. And this means that in order to be able to answer the second question (How do we know if an appeal to authority is inappropriate?), one needs simply to know who is expert in which area, what they assert, and to which area these assertions belong.

The situation becomes more complicated at a closer look. Walton lists a number of questions one has to ask to establish the truth of the premises (ibid., p. 25):

1. Expertise Question: How credible is E as an expert source?

2. Field Question: Is E an expert in the field that A is in?

3. Opinion Question: What did E assert that implies A?

4. Trustworthiness Question: Is E personally reliable as a source?

5. Consistency Question: Is A consistent with what other experts assert?

6. Backup Evidence Question: Is E’s assertion based on evidence?

While these questions are clearly relevant, it is important for us to note that in order to be able to tell whether an authority appeal is correct, one needs to possess a huge amount of knowledge. Elements of this knowledge are of various nature: knowledge of ‘fields’ (like scientific disciplines and sub-specializations), degrees of credibility (like scientific rankings, credentials, institutions and statuses), logical relations of assertions in a technical field, other experts and their claims, personal details, matters concerning what it means to be evidentiary support, etc. In the pessimistic reading this scenario suggests that laypersons will hardly be able to acquire all this knowledge, appeals to authority will generally be insufficiently supported, and that the interlocutors of a discussion (if they themselves are not experts in the field in question) will rarely be able to tell whether an appeal to authority is appropriate or not. In the optimistic reading it points out themes and areas that are primarily relevant to the first question, through the second question to which the first is intimately connected, and it embeds the problem of ad verecundiams in a specific theoretical context in which they can be analyzed.

While Walton’s approach focuses on what it means for an expert claim to be unreliable (‘incorrect authority’), the pragma-dialecticians place the emphasis on the use of authority appeals (‘incorrect appeal’). According to their functionalization principle, one needs to look at the function of an assertion within the discourse in order to tell whether it contributes to the final dialectical aim of rationally resolving differences of opinion. Fallacies are treated as violations of those rules of rational discussion that facilitate this resolution. In one of their book (Eemeren & Grootendorst 1992, pp. 212-217), they use the ad verecundiam to illustrate that the same type of fallacy (as understood traditionally) can violate different rules at different stages of the dispute, and thus it can serve various purposes. An ad verecundiam argument can thus violate the Argument Scheme Rule at the argumentation stage, i.e. the interlocutor can present an appeal to authority instead of a correctly applied and appropriate argument scheme when defending her standpoint. But ad verecundiams can also be used at the opening stage to violate the Obligation-to-defend Rule: a party refuses to provide adequate argumentative support for her claim when asked, and offers an appeal to authority instead. Moreover, they can violate the Relevance Rule in the argumentation stage again, when authority appeals are used as non-argumentative means of persuasion.

Just as the pragma-dialectical approach offers a radically different answer from Walton’s to the question of what it means for an appeal to authority to be incorrect, the possible answers to the question of how to recognize these incorrect appeals are also strikingly different in the two cases. For pragma-dialecticians, one needs to identify the function of such appeals in the context of the entire dispute as reconstructed according to a fully-fledged theory with its stages and rules and further assumptions. Pragma-dialectics offers an exciting framework in which one can focus on the pragmatic use of elements in argumentation, but it pays less attention to the study of what is used. Surely, an appeal to authority can often be used as to evade the burden of proof, or to intimidate the other party by non-argumentative means, but in many other cases it is simply unavoidable to defer to expert testimonies, even among rational discussants engaged in a critical dispute. As the next section argues, such appeals are actually so widespread and indispensable that the study of abusive appeals seems only secondary in importance.

This paper studies problems that are more similar to Walton’s questions than to the issues raised by the pragma-dialectical approach, although it does not accept the inferentialist framework with its interest in argument schemes (in that the focus will be on elements of knowledge answering Walton’s questions, rather than seeing these elements as connected in an argument scheme). The possibility of ad verecundiam arguments, just as the possibility of correct authority appeals, depends on non-experts’ ability to evaluate the reliability of expert claims. In the followings, recent philosophical and sociological discussions will be summarized in order to investigate such possibilities.

2. Some recent approaches to expertise

It is a common recognition among many fields that, in present cultures, the epistemic division of labor has reached a degree where trust in expert opinions is not only indispensible in many walks of life, but also ubiquitous and constitutive of social existence. Thus the problem of expertise has gained increasing focus in psychology (Ericsson et al. 2006), in philosophy (Selinger and Crease 2006), or in the social studies of science where the initiative paper by Collins and Evans (2002) has become one of the most frequent points of reference in the field. Other forms of an ‘expertise-hype’ can be seen in the theory of management, in risk assessment, in artificial intelligence research, in didactics, and in a number of other fields having to do with the concept of ‘expert’.

For the present purposes, a useful distinction is borrowed from recent literature on the public understanding of science. Two approaches are contrasted to frame the expert-layperson relationship for the case of science: the deficit model and the contextual model (Gross 1994, Gregory and Miller 2001). In the deficit model the layperson is viewed as someone yet ignorant of science but capable of having their head ‘filled’ with knowledge diffusing from science. Such a ‘filling process’ increases, first, laypeople’s scientific literacy (and their ability to solve related technical problems), second, their degree of rationality (following the rules of scientific method), and third, their trust in and respect for science. Recently, this model has been criticized as outdated and suggested to be replaced by the contextual model, according to which members of the public do not need scientific knowledge for solving their problems, nor do they have ‘empty memory slots’ to receive scientific knowledge at all. Instead, the public’s mind is fully stuffed with intellectual strategies to cope with problems they encounter during their lives, and some of these problems are related to science. So the public turn to science actively (instead of passive reception), more precisely to scientific experts, with questions framed in the context of their everyday lives.

The strongly asymmetrical relationship between experts and the public suggested by the deficit model is at the background of a groundbreaking paper by the philosopher John Hardwig (1985), who coined the term ‘epistemic dependence’. His starting point is the recognition that much of what we take to be known is indirect for us in the sense that it is based on our trust in other people’s direct knowledge, and the greater the cultural complexity is, the more it is so. Hardwig takes issue with the dominantly empiricist epistemological tradition, where these elements of belief are not considered rational inasmuch as their acceptance is not based on rational evidence (since the testimony of others does not seem to be a rational evidence).

Hardwig takes a pessimistic position regarding the possibility of laypeople’s assessment of expert opinions: since laypeople are, by definition, those who fall back on the testimony of experts, they have hardly any means of rationally evaluating expert claims. Of course, laypeople can ponder on the reliability of certain experts, or rank the relative reliability of several experts, but it can only be rationally done by asking further experts and relying on their assessments – in which case we only lengthened our chain of epistemic dependence, instead of getting rid of it (p. 341). So, according to Hardwig, we have to fully accept our epistemic inferiority to experts, and either rely uncritically on expert claims or, even when criticizing these claims, we have to rely uncritically on experts’ replies to our critical remarks (p. 342).

However, at one point even Hardwig admits that laypeople’s otherwise necessary inferiority can be suspended in a certain type of situations that he calls ad hominem (p. 342):

The layman can assert that the expert is not a disinterested, neutral witness; that his interest in the outcome of the discussion prejudices his testimony. Or that he is not operating in good faith – that he is lying, for example, or refusing to acknowledge a mistake in his views because to do so would tend to undermine his claim to special competence. Or that he is covering for his peers or knuckling under to social pressure from others in his field, etc., etc.

But Hardwig warns us that these ad hominems “seem and perhaps are much more admissible, important, and damning in a layman’s discussions with experts than they are in dialogues among peers”, since ad hominems are easy to find out in science via testing and evaluating claims (p. 343). And apart from these rare and obvious cases, laypeople have no other choice left than blindly relying on expert testimonies.

Nevertheless, Hardwig’s examples imply that in some cases it is rational and justified for a layperson to question expert testimonies. Recent studies on science have pointed out various reasons for exploiting such possibilities. For instance, there are formal contexts at the interfaces between science and the public, such as legal court trials with scientific experts and non-expert juries, where laypeople’s evaluations of expert claims are indispensible. Such situations are considered by the philosopher of law Scott Brewer (1998), who lists what he identifies as possible routes to ‘warranted epistemic deference’, i.e. means of non-expert evaluation of expert claims.

Substantive second guessing means that the layperson has, at least to some degree, epistemic access to the content of expert argument and she can understand and assess the evidences supporting the expert claim. Of course, as Brewer admits, such situations are rare since scientific arguments are usually highly technical. But even with technical arguments one has the option of using general canons of rational evidentiary support. If an expert argument is incoherent (e.g. self-contradicting) or unable to make or follow basic distinctions (in his example, between causing and not preventing) then, even for the layperson, it becomes evident that such an argument is unreliable. Laypersons can also judge by evaluating the demeanor of the expert: they may try to weigh up how sincere, confident, unbiased, committed etc. the expert is, and this obviously influences to what degree non-experts tend to rely on expert claims. However, all this belongs to the ethos of the speaker and Brewer emphasizes the abusive potential in demeanor often exploited by the American legal system. The most reliable route, according to him, is the evaluation of the expert’s credentials, including scientific reputation. He adopts the credentialist position even while acknowledging that it is laden with serious theoretical difficulties, such as the regress problem (ranking similar credentials requires asking additional experts), or the underdetermination problem (similar credentials underdetermine our choice between rivaling experts).

Another reason for focusing on the possibility of lay evaluations of expert claims is the recognition that experts do not always agree with one another, and such situations are impossible to cope with in terms of simple epistemic deference. According to the contextual model, the public need answers to questions they find important (regarding health, nutrition, environmental issues, etc.), and these questions typically lack readymade consensual answers in science. Alvin Goldman, a central figure in social epistemology, tries to identify those sources of evidence that laypeople can call upon when choosing from rivaling expert opinions – in situations where epistemic solutions of ‘blind reliance’ break down (Goldman 2001).

Goldman distinguishes between two types of argumentative justification. ‘Direct’ justification means that the non-expert understands the expert’s argument and is able to evaluate it, similarly to what Brewer means by substantive second guessing. But when arguments are formulated in an unavoidably esoteric language, non-experts still have the possibility to give ‘indirect’ justification by evaluating what Goldman calls argumentative performance: certain features of the arguer’s behavior in controversies (quickness of replies, handling counter-arguments, etc.) indicate the degree of competence, without requiring from the non-expert to share the competences of the expert. Additional experts can be used in two ways in Goldman’s classification: either by asking which of the rivaling opinions is agreed upon by a greater number of experts, or by asking meta-experts (i.e. experts evaluating other experts, including credentials) for judgment on the expert making the claims. Similarly to Hardwig’s ad hominem cases, Goldman also considers the possibility of identifying interests and biases in the arguer’s position. But what he sees as the most reliable source of evidence is track-record. He argues that even highly esoteric domains can produce exoteric results or performances (e.g. predictions) on the basis of which the non-expert becomes able to evaluate the cognitive success of the expert.

Despite their different answers to the question of most reliable decision criteria, Brewer and Goldman agree that sounder evaluation needs special attention, either by studying the institutional structure of science (to weigh up credentials) or by examining specialists’ track-records. But why should the public take the effort of improving their knowledge about science? If we turn from philosophical epistemology to the social studies of science and technology, we find an answer at the core of the discipline: because laypeople’s lives are embedded in a world in which both science and experts play a crucial role, but where not all experts represent science and even those who do, represent various, often incompatible, claims from which laypeople have to choose what to believe.

The program called ‘studies of expertise and experience’ (SEE) evolved in a framework shaped by these presuppositions, initiated by science studies guru Harry Collins and Robert Evans (2002, later expanded to 2007). Their initial problem is that “the speed of politics exceeds the speed of scientific consensus formation” (Collins and Evans 2007: 8), meaning that decision making processes outside science (politics, economy, the public sphere, etc.) are usually faster than similar processes in science. This gives rise to what they call ‘the problem of legitimacy’ (Collins and Evans 2002: 237): how is technological decision making possible given the growing social uncertainty? They claim that solutions are already achieved, or pointed to, in the field of ‘public participation in science’. However, a related but yet unsolved problem is ‘the problem of extension’, i.e. to what degree should the public be engaged in technical decision making? The program of SEE is meant to provide normative answers to this question.

In this framework the term ‘expert’ has a wide range of applications, since experts are defined as those “who know what they are talking about” (Collins and Evans 2007: 2), which is based on immersion in communicative life forms. Forms of expertise range from ubiquitous skills (such as native language usage) to the highest degree of scientific specialization, as summarized in ‘the periodic table of expertises’ (p. 14). This table includes, in addition to types of specialist expertise, those forms of ‘meta-expertise’ that can be used to judge and evaluate specialist expertise.

According to the SEE, the public live in a society where they are conditioned to acquire skills and ‘social intelligence’ needed to cope in an expert culture. Non-experts are able to come to decisions regarding technical questions on non-technical grounds, based on their general social intelligence and discrimination. As Collins and Evans claim (p. 45), the “judgment turns on whether the author of a scientific claim appears to have the appropriate scientific demeanor and/or the appropriate location within the social networks of scientists and/or not too much in the way of a political and financial interest in the claim”. So people (or at least sufficiently informed people) in Western societies have enough social skills to form correct judgments (in their examples, about astrology, or manned moon landings, or cold fusion) without possessing field-specific technical knowledge. Also in their ‘periodic table’ one can find ‘meta-criteria’ for evaluating experts, such as credentials, past experience and track record, but all these criteria need special focus on the layperson’s side to asses, apart from their basic general social skills.

To sum up the main points of this section: It seems clear that despite all the possible theoretical difficulties, laypeople can and do make evaluations of expert claims, and since laypeople are not experts in terms of their cognitive domains, these evaluations are based on criteria external to the specialist domain. Also, such external evaluations are not only frequent but generally unavoidable in a world of rivaling experts and consensus-lacking controversial issues. But while these philosophical analyses give rise to different while partly overlapping normative solutions, it remains unclear whether these solutions are really functional in real life situations. The next section attempts to examine this question.

3. A rough case study

The recent worldwide public interest in the H1N1 influenza pandemic threat , and in the corresponding issues concerning vaccination, provides a highly suitable test study for the above theoretical approaches. First, the case clearly represents a technical topic about which various and often contradicting testimonies were, and still are, available. Second, despite the lack of scientific consensus, decisions had to be made under uncertain circumstances, both at the level of medical policy and at the level of individual citizens who wanted to decide eagerly whether vaccination (and which vaccination) is desirable. Huge numbers of non-experts were thus forced to assess expert claims, and come to decisions concerning technical matters lacking the sufficient testimonial support.

Luckily, the internet documented an overwhelming amount of lay opinions, mostly available in the form of blog comments. In order to see how laypeople do assess expert claims, I looked at four Hungarian blog discussions (as different as possible) on the issue, examined 600 comments (from October-November 2009) trying to identify explicitly stated criteria of evaluative decisions that I found in 110 cases.[ii] The work is rather rudimentary and methodologically rough at the moment, but it may suffice to yield some general results to be tested and elaborated by future work. I approached the material with a ready-made typology of warrants abstracted from the theoretical literature, and I counted the number of instances of the abstract types. I disregarded those comments which did not contain any clear opinion, or where arguments (reasons, warrants) were not given in favor of (or against) the standpoint, or which were redundant with respect to earlier comments by the same user. Some comments contained more than one type of argument or warrant, where all different instances were considered. The tested categories distilled from the literature cited in the previous section are the following.

(1) The first group is argument evaluation by the content, i.e. Brewer’s ‘substantive second guessing’ or Goldman’s ‘direct argument justification’, when laypersons interiorize technical arguments as their own and act as if they had sufficient cognitive access to the domain of expertise. Example: “I won’t take the vaccine, even if it’s for free in the first round. The reason is simple: the vaccine needs some weeks before it takes effect, and the virus has a two week latency. And the epidemic has already begun…” (cotcot 2009, at 10.06.13:06).

(2) The second group contains those contextual discursive factors that are indirectly tied up with the epistemic virtue of arguments. (2a) Such is the consistency (and also coherence) of arguments, clarity of argument structure, supporting relations between premises and conclusions, etc. Example: “Many of those who go for this David Icke type humbug are afraid of the crusade against overpopulation, so they’re against inoculation, which is a contradiction again” (cotcot 2009, at 10.05.22.:43). (2b) A similar matter is the degree of reliability of argument scheme used by the expert. Arguments can be weakened, albeit at the same time increased in persuasive potential, by different appeals to emotions and sentiments, or by abusive applications of ad hominems, or by irrelevant or misleading appeals to authority, etc. Also, dialectical attitude (instead of dialectical performance) can be highly informative, i.e. moves and strategies in controversies, including conscious or unnoticed fallacies such as straw man, red herring, question begging, shifting the burden of proof, and more generally, breaking implicit rules of rational discussion. I found that these kind of assessments are very rare, still an arguable example is: “It is a bad argument that something is a good business. Safety belt is also a good business for someone, and I still use it.” (vastagbor 2009, at 11.04.14:52)

(3) Hardwig, Goldman and the SEE all emphasize the role of detecting interests and biases. Considering these factors belongs to the field of ‘social intelligence’, and precisely because these are ubiquitous they do not need focused effort and training to improve (as opposed to the argumentative factors mentioned above). Example: “I’d be stupid to take the vaccine. All this mess is but a huge medicine business.” (vastagbor 2009, at 11.04.12:26)

(4) Social intelligence covers the ability to evaluate the reliability of experts, instead of judging the arguments. (4a) The simplest case is unreflected deference or blind trust. Example: “My aunt is a virologist and microbiologist. She never wants to persuade me to take any vaccination against seasonal flu, but this time it is different…” (reakcio 2009, at 11.14.15:21) (4b) As the credentialist solution suggests, laypeople can estimate the formal authority of different experts by judging their ranks or positions. Example: “So, when according to the Minister of Healthcare, and also to Czeizel [often referred to as “the doctor of the nation”], and also to Mikola [ex-Minister of Healthcare], Hungarian vaccine is good, then whom the hell would I believe when he says that it isn’t?” (szanalmas 2009, at 11.04.12:22) (4c) Also, quite similarly, one may discredit testimonies by claiming that the expert is a wrong or illegitimate authority. Example: “Why should I want to believe the doctor who tried to convince my wife not to take the vaccine a few days ago, and then tried to rope her in Forever Living Products? Or the doctor who does not even know that this vaccine contains dead virus, not live? […] So these are the experts? These are the doctors to protect our health? ” (szanalmas 2009, at 11.04.12:22)

(5) Finally, there are various forms of commonsensical social judgments not explicitly dealing with interests or authorities, as expected by the SEE programme. Three examples: “Let us not forget that first there wasn’t even a date of expiry on the vaccine” (vastagbor 2009, at 11.04.12:00). “This huge panic and hype surrounding it makes things very suspicious” (vastagbor 2009, at 11.04.12:02). “The vaccine comes from an unknown producer, and the formula is classified for 20 years…” (szanalmas 2009, at 11.03.16:01).

The results are summarized by the table below:

| “cotcot” | “szanalmas” | “vastagbor” | “reakcio” | in total | |

| number of comments | 87 | 140 | 224 | 150 | 601 |

| Type 1 (judgment by content) |

5 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 15 |

| Type 2a (argument structure) |

2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Type 2b (argument scheme) |

0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Type 3 (interests, biases) |

10 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 26 |

| Type 4a (unreflected deference) |

6 | 0 | 4 | 7 | 17 |

| Type 4b (formal authority) |

1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Type 4c (illegitimate authority) |

3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Type 5 (“social” judgments) |

6 | 8 | 11 | 14 | 39 |

Table 1. Number of argument type instances in blog comments

Judgment by content (type 1) is quite frequent, contrary to the recommendation of normative approaches emphasizing that the demarcation between experts and laypeople correlates with the distinction between those who have the ability to understand technical arguments and those who do not. There are several possible reasons for this. One is that laypeople do not like to regard themselves as epistemically inferior, and try to weigh up expert arguments by content even if they lack the relevant competences. Another is that the publicly relevant technical aspects of the H1N1 vaccine issue are far less esoteric than for many other scientific issues, and there is a lot to understand here even for non-virologists and non-epidemiologists. Another is that while people form their opinions on testimonial grounds, they often refrain from referring explicitly to their expert sources (especially in blog comments resembling everyday conversations), and state their opinion as if they themselves were the genuine source.

In contrast, assessment informed by argument structure and form (types 2a and 2b) is pretty rare, even when it seems plausible to assume that, in some respect, judgments on general argumentative merits require different competences from the specialist judgments based on content. But just as most people are not virologists, they are very rarely argumentation theorists, so they are usually not aware of the formal structure or type of arguments they face, or the relevant fallacies.

The identification of interests and biases (type 3) is a really popular attitude in the examined material. While part of the reason for this might be that the studied case is untypical in that very clear interests were at play (the vaccine producer company seemed to have some connections with certain politicians), this popularity is nevertheless in line with the expectation shared by most of the cited authors about the relative importance of such considerations.

Also, simple deference (type 4a) is a relatively widespread attitude, despite the fact that contradicting expert testimonies were obviously available in this specific case. While Brewer and Goldman suggest ranking and comparing expert authorities, it seems that such ranking is pretty rare in actual arguments. Neither considering formal or institutional indicators of authority (type 4b) nor questioning the legitimacy of putative experts (type 4c) seem frequent. Perhaps this is partly because people tend to base their trust on personal acquaintances (the SEE calls this ‘local discrimination’). Another likely reason is the public’s relative ignorance in the field of scientific culture and social dimension of the workings of science: unlike other important cultural spheres like that of politics, economy, or sports, about which laypeople are more likely to make reliable social evaluations, science as a social system is hardly known by the public.

What I found to feature most often in laypeople’s decisions is ‘commonsensical’ forms of social judgments, practically those that consider factors other than direct interests or expert authorities. Obviously, social structures and mechanisms are easier to understand (based on our fundamental experience with them) than technical arguments, even if peculiar features of the social world of science are much less widely known than the social reality in general.

In sum, public assessment of expert claims is based on skills and competences acquired through everyday social interaction, and the applicability of these skills in restricted cognitive domains is generally presupposed without further reflection. While the deficit model suggests either blind reliance or the acquisition of the same domain-specific cognitive skills shared by experts, the contextual model points to the possibility of a kind of contextual knowledge that would enable the public to assess expert claims more reliably than merely adopting the most general social discriminations, without having to become experts themselves in all the fields in which they need to consult experts. However, it seems that the evaluative criteria suggested by normative accounts are rarely used in actual decisions.

4. Conclusion

If we set aside the question of how expert authority appeals are used inappropriately and, instead, focus on what it requires to tell whether an expert argument is reliable at all – which is essential when critical discussions are aimed at rational decisions – then it turns out that the depth and range of knowledge required from the public seems to escape the confines of the study of argumentation in general. Surely, evaluations of expert claims supported by arguments can be significantly improved by awareness of some basic concepts in argumentation studies, regarding e.g. the consistency (and also coherence) of arguments, clarity of argument structure, relations between premises and conclusions, argument schemes and their contexts, fallacious argument types, etc. However, it is important to realize that an even more efficient support to such evaluations can be gained by some familiarity with the social dimension of science (as opposed to technical knowledge in science, restricted to experts): credentials, hierarchies of statuses and institutions, types and functions of qualifications and ranks, patterns of communication in science, the role of different publications and citations, mechanisms of consensus formation, disciplinary structures, the nature of interdisciplinary epistemic dependence and resulting forms of cooperation, etc.

While this contextual (rather than substantial) knowledge about science may be essential in societies that depend in manifold ways on the sciences, it is not obvious how and why the public attention could turn to these matters. If spontaneous focus on scientific expertise might be unrealistic to expect from the public, there are organized ways to improve cognitive attitudes toward science. One relevant area is school education where, in most countries at present, science teaching consists almost exclusively of scientific knowledge at the expense of knowledge about science (and awareness of argumentation is also rather rare in school curricula). Another area is science communication, including popular science and science news, where contextual information about matters mentioned above is typically missing but would be vital for enhancing understanding. Also, improving forms of public participation in, or engagement with, science is an obvious way to increase public interest and knowledge.

All in all, as our cultural dependence on cognitive experts has been recognized as a fundamental feature of our world, the problem of appeals to expert authorities seems both more complex and more crucial than when viewed simply as an item on the list of fallacy types in argumentation studies. The paper tried to show that the study of argumentation can shed light on some important aspects of authority appeals. However, this does not mean that the problem of expertise is, or should be, a substantive field of argumentation studies, or that argumentation theorists should substantially evaluate claims made by experts. But argumentation studies (as a field of expertise itself) can obviously offer important contributions to the study of expertise, especially when theoretical approaches are supplemented with an empirical study of argumentative practice. Such a perspective may put the emphasis on aspects that are, as seen in pragma-dialectics, rather different from the traditional question of ‘How do we know that the discursive partner appealed to the wrong expert claim?’ The latter problem is also vital, and in order to tell how to answer it one needs to find out a good deal about science and its relation to the public. The best way to do so seems to be to consult, or better cooperate with, those disciplines that take related problems as their proper subject.

NOTES

[i] The work was supported by the Bolyai Research Scholarship, and is part of the HIPST project. For section 2, the paper is partly based on an earlier work to be published in Teorie Vĕdi (‘Contextual knowledge in and around science’), while the empirical work presented in section 3 was done for Kutrovátz (2010).

[ii] The four blogs are: cotcot (2009) – an online fashion and health magazine (mostly for and by women); szanalmas (2009) – an elitist community blog site, often highly esteemed for intellectual autonomy; vastagbor (2009) – a political blog with marked right-wing preferences; reakcio (2009) – a cultural/political blog with right-wing tendencies.

REFERENCES

Brewer, S. (1998). Scientific Expert Testimony and Intellectual Due Process. The Yale Law Journal, 107, 1535-1681.

Collins, H., & Evans, R. (2002). The third wave of science studies: Studies of expertise and experience. Social Studies of Science, 32, 235-296.

Collins, H., & Evans, R. (2007). Rethinking Expertise. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

cotcot (2009). http://cotcot.hu/test/cikk/4819. Cited 14 July 2010.

Eemeren, F. H. van, & Grootendorst, R. (1992). Argumentation, Communication, and Fallacies. New Jersey & London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Ericsson, K. A., Charness, N., Feltovich, P. J., & Hoffman R. R. (Eds.) (2006). The Cambridge handbook of expertise and expert performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Goldman, A. I. (2001). Experts: which ones should you trust? Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 63, 85-109.

Gregory, J., & Miller, S. (2001). Caught in the Crossfire? The Public’s Role in the Science Wars. In J. A. Labinger & H. Collins (Eds.), The One Culture? A Conversation about Science (pp 61-72). Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

Gross, A. G. (1994). The roles of rhetoric in the public understanding of science. Public Understanding of Science, 3, 3-23.

Hardwig, J. (1985). Epistemic dependence. The Journal of Philosophy, 82, 335-349.

Kutrovátz, G. (2010). Trust in Experts: Contextual Patterns of Warranted Epistemic Dependence. Balkan Journal of Philosophy, 2, 57-68.

reakcio (2009). http://reakcio.blog.hu/2009/11/04/a_felelem_bere_6_milliard?fullcommentlist=1. Cited 14 July 2010.

Selinger, E., & Crease, R. P. (Eds.) (2006). The philosophy of expertise. New York: Columbia University Press.

szanalmas (2009). http://szanalmas.hu/show_post.php?id=64722. Cited 14 July 2010.

vastagbor (2009). http://vastagbor.blog.hu/2009/11/04/kave_vagy_vakcina_tokmindegy_ki_gyartja. Cited 14 July 2010.

Walton, D. (1997). Appeal to Expert Opinion. University Park, Pa.: Penn State University Press.