ISSA Proceedings 2010 – The Inferential Work Of The Addressee: Recovering Hidden Argumentative Information

In a recent book (Lo Cascio 2009) was suggested that people from the south of Europe leave a lot of information unsaid, requiring of the decoder the very arduous task of filling the non given or unwritten information, and of recovering the content of the real, or deep meaning of the surface sentence or message. Actually, for somebody who comes from the Mediterranean area or Middle East, there are three ways of communicating:

In a recent book (Lo Cascio 2009) was suggested that people from the south of Europe leave a lot of information unsaid, requiring of the decoder the very arduous task of filling the non given or unwritten information, and of recovering the content of the real, or deep meaning of the surface sentence or message. Actually, for somebody who comes from the Mediterranean area or Middle East, there are three ways of communicating:

1. The encoder gives only a partial message and the decoder must be intuitive enough to recover and to complete the remaining missing information. This gives the opportunity to the encoder to partially manifest his thoughts and hence the possibility to change his message according to the situation.

2. The encoder says something, but the real meaning of the message is something else. The decoder must then be capable of understanding the real message, i.e. of decoding the surface message but recovering its deep meaning. The advantage of this way of communicating for the encoder is enormous on the condition that the right decoder understands the real message. Understanding is based a) on the knowledge that the decoder has at disposal regarding the encoder’s background as well as b) on the evaluation he is able to give of the message he receives, according to the particular situation. Imagine for instance that somebody at a dinner says to someone else:

(1) I think they forgot to invite Heineken

in order to say:

(2) I am missing a glass of beer

3. The encoder does not say anything, but expresses his idea exclusively by means of his facial expression. The decoder then must be able to understand the situation and act accordingly.

Certainly, not a very easy way to communicate, one which requires a very good knowledge on behalf of the decoder, of the encoder and the situation. It requires a strong inferential competence, which is a very hard and risky work, a good inferential exercise that not everyone is able to carry out successfully. As a matter of fact the encoder takes into consideration the potential knowledge of the decoder, knowledge, which enables the addressee to complete his message. This is the reason why the encoder gives partial rather than complete information to his addressee. The addressee must not only interpret the message, but also recover the remaining or presented implicit information. He must also (and he cannot avoid doing so) fill the gaps in the information with data of his own. The encoder speculates in other words on the addressee’s capacity to fill the unsaid or not mentioned information. For instance if an encoder says:

(3) There is no use to continue the discussion

or

(4) Let us change the subject

or

(5) Were you not going home?

or

(6) Enough!

the addressee has to interpret the kind of discussion that should not be continued. In addition, on his own, he must trigger the conclusion that he is to stop arguing, a conclusion, which was not explicitly given by the encoder. Actually, in communication a lot of information would be redundant or unnecessary. This allows to save time, space and to keep conversation down to the essential. A message is in fact always incomplete. The encoder only gives the information he considers sufficient to the addressee, and in particular to that specific addressee. As Ducrot (1972, p.12) states “le problème général de l’implicite est de savoir comment on peut dire quelque chose sans accepter pour autant la responsabilité de l’avoir dite, ce qui revient à bénéficier à la fois de l’efficacité de la parole et de l’innocence du silence”.

In this paper I want to show that argumentation as well as narration always require a lot of inferential and reconstructive work from the receiver since a lot of information remains hidden. In the narrative or argumentative reconstruction the decoder is free to follow his own path on the condition that he is respectful of congruence principles and of linguistic rules. In other words, as it will be shown, a sophisticated inferential argumentative competence is needed.

1. Argumentative and Narrative Strategy

Let us state that the encoder is always speculating on the inferential capacity of the addressee, using it as an argumentative or even a narrative strategy. The “argumentative” encoder uses this type of strategy because he doesn’t need to give (exhaustive) argumentative justifications, taking a stance, in the expectation that the decoder will find justifications on his own. It could also be a narrative strategy, because the encoder gives to the addressee the opportunity to personalize the story by filling it with personal information, freely, but on condition that it is congruent with the prior information given to him by the encoder. Every addressee is, as a matter of fact, accustomed to constantly developing inferential work. The quantity and quality of this inferential work depends on the knowledge, fantasy, cultural background, emotions (Plantin 1998), and inferential capacity of each addressee. For example in the following passage (Christie 1971, pp. 13-14):

(7) he snapped the case open, and the secretary drew in his breath sharply. Against the slightly dingy white of the interior, the stones glowed like blood.

“My God!, sir,”, said Knighton. “Are they – are they real?”.

“I don’t wonder at your asking that. Amongst these rubies are the three largest of the world ……..You see, they are my little present for Ruthie”.

The secretary smiled discreetly.

“I can understand now Mrs. Kettering’s anxiety over the telephone,” he murmured.

But Van Aldin shook his head. The hard look returned to his face:

“You are wrong there,” he said. “She doesn’t know about these; they are my little surprise for her.”

The character Knighton infers that Mrs. Kettering was anxious because of the quality and the size of the jewels she was about to receive. A possible logical inference, which nevertheless unfortunately appears to not correspond with reality. According to Mr. Van Aldin, Mr. Knighton formulated the wrong hypothesis since Mrs. Kettering didn’t know that she was going to receive the jewels as a gift. Mrs. Kettering’s anxiety then, must be based on something else.

By means of narrative text, the decoder may at every step anticipate the coming events. He may also imagine the situation in which the events take place, using a great deal of the information, given to him by the encoder, and filling the rest with his own reasoning, knowledge and imagination. As a matter of fact, he can imagine a lot of things and in other words weave everything into a personal story. Let us take the incipit of a novel (B. Moore 1996, p.1):

(8a) R did not feel at home in the south. The heat, the accents, the monotony of vineyards, the town squares turned into car parks, the foreign tourists bumping along the narrow pavements like lost cows.

Step by step the decoder must follow the linguistic profile of the message. He may imagine a southern region (of America or of Europe or elsewhere), a warm south, far too warm, perhaps, for character R to feel home. It is not clear whether he/she is a man or a woman, whether he/she is young or old. Perhaps an adult man. As a matter of fact “the heat, the monotony, the cars, the tourists” could be the reason for the character not feeling at home. The decoder imagines that maybe R comes from the north. It must be a white man. Maybe at the location there is the sea. This information is inferred from the fact that, tourists are mentioned, even if there is no specific indication about the presence of water and beaches. Nevertheless this is information, which, even if not present in the text, it can be recovered in order to complete the scenario. There is then an obliged interpretation and an optional filling in of the details in order to complete the scenario. The story nevertheless continues:

(8b) Especially the tourists they were what made it hard to follow the old man on foot.

The information: “to follow the old man on foot”, triggers questions such as: Who could the old man be? Why follow him? Is he a criminal? Is he someone who is being searched? Perhaps he has committed a homicide? Otherwise, why follow him? And who is character R anyway? Could he be a policeman? A detective? Someone hired to follow the old man? And so on. But suddenly the following information is given:

(8c) R had been in Salon de Provence for four days, watching the old man. It looked right. He was the right age. He could be the old man who had once been the young man in the photograph. Another thing that was right: he was staying in a Benedictine monastery in the hills above Salon. It was a known fact that the Church was involved.

The location is then Salon de Provence, which in turn places the story in southern France, where perhaps there is no sea, or is there? The decoder has to adjust his inferential route (from south of the Americas) and imagine himself being in Europe, with other buildings, in a complete different atmosphere.

The author of the message does not give a great deal of details. How, for instance, does the old man look? It is not clear whether this is important or not, but the decoder cannot refrain from giving him a vague shape, one which is adaptable to the role of an “old” man who is being followed. Of course, as the story progresses the decoder will gather more details but in the meantime he cannot avoid wondering what the person did in order to be shadowed in this way. If he is old maybe the story has to do with something that happened many years ago.

For this argumentative inferential work he can imagine an interlocutor whom is presenting his reasoning. As the story progresses a mental change takes place at every step (Gardner 2004). The modification forms the basis for understanding and decoding the rest of the message. Everything is plausible and personal. At every step the decoder, as a matter of fact, can construct a world where all the events and situations he imagines are possibly true, as long as they are congruent with the information he has thus far received. That is, he waits for corrections on behalf of the encoder while he continues on reading the story. But how does the inferential work takes place? Which constraints are involved?

2. Narration argumentation and the congruency principles

Narration is characterized by two main categories: Event (E) and Situation (S). The difference between the two categories is an aspectual one. Events are states of affairs presented as closed time intervals. Therefore they have a starting point and an end point. Situations on the contrary are states of affairs presented as open time intervals. Situations always mark and refer to an event in the same world. They include in other words the time interval of the event they are marking (cf. Adelaar & Lo Cascio 1986, Lo Cascio & Vet 1986, Lo Cascio 1995, Lo Cascio 2003). A sentence as

(9) It was very warm (S1) and she went out to buy a ice cream (E1). Then she saw John (E2) going to the station (S2). He was carrying a big suitcase (S3)

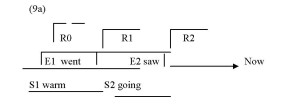

In (9) the situation S1, it was warm, includes and covers the event E1, she went out: S1≥E1. Situations, in other words, can indicate properties, or, so called, characteristics, of a world to which an event belongs. (9) can be analyzed as (Figure 1):

In (9a), S1 and S2 are open time intervals. E1 takes place within the time interval R0 (reference initial) and delivers the starting point for R1 (reference time for E2). E2 takes place within R1 and delivers R2 (reference time 2 where an other event can take place), and so on. A chain of events and situations forms a story. Situations describe the world and are the background of it, while events change that world.

Every event or situation in order to take place or to be true must meet a Congruency Principle. The congruency principle defines the semantic, encyclopaedic, pragmatic conditions according to which a type of event or situation is allowed in a specific world. Every new state of affairs must meet that principle, i.e. must be compatible and acceptable for the specific world to which it will belong. According to the congruency principle:

an event or situation can take place in a world W or belong to a world W, or can be imagined to take place in a world W, at the condition that it is in harmony and coherent with the already existing states of affairs and characteristics of that world.

Every event or situation, as a matter of fact, delivers the conditions or bases, which are needed in a specific world in order to understand and make possible that a new event comes, or is allowed to change that world. After events have taken place, the world is changed and a new situation is created as a result, which is determinant, within the new reference time, for which new specific events or situations can take place. The events changing into situation in the world, become, so to say, part of the memory of that world where they have left a trace.

According this analysis, in narration, every event, after having taken place and having created a reference time (or world), becomes a background information for another new event, which will be added to the same time axis and anchored within that reference time. It could be said, in cognitive terms, that our knowledge is, in this way, built up as a form of addition, of a piling up.

Every addressee (reader or listener) at every stage of the story can imagine or guess which events or situations are going to take place, choosing between all those that are allowed according the congruency principle (cf. Lo Cascio 1997). The set of possible states of affairs, which can belong to a specific world, is part of the encyclopaedic knowledge of each speaker, but the set changes, in entity and quality, according the specific knowledge a speaker has. Nevertheless, in the reality the encoder often makes a different choice than the decoder, so that it is frequently a surprise for the reader, or the listener, the way a story continues and develops. This is the nice play in the interaction between encoder and decoder(s).

Argumentative texts show the same behaviour. They are characterized by three components: 1) a statement, 2) at least a justification for that statement, and 3) a general rule on which the justification is based. In the argumentative and inferential reconstruction procedure, the main guide is then the congruency principle, with the help, for argumentative text, of the general rule, the warrant, which makes it possible and justifies that a specific argumentative relationship holds.

It is evident that, normally, the imagination of the decoder works very arduous and quickly in the process of logically reconstructing or constructing the reasoning or the story. For some readers or hearers this work is much harder than for others. It depends on the inferential habits, attitude, and compulsory need of being involved in a story or reasoning. It also depends on whether the addressee has an interest in continuing with filling in the story or the reasoning in his own way or not.

In oral communication the time span for a reaction is decided by the encoder, while in a written communication the decoder can take time and “enjoy” the story or reasoning according to his desire and choice. The longer he takes the more possible reconstructions and constructions he will be able to make. In the activity of interpreting, the text must be analysed step by step. A number of inferences can be drawn and a lot of them must remain personal. Other inferences must be congruent with the intention of the encoder, and follow the same course of the encoder even if the addressee anticipates it. Every addressee has to make conjectures in order to fill in information not provided with the intention of reconstructing the context in which things happen, and in order to anticipate things, which are coming. In other words, what the decoder needs to do is choose between a course he is guessing the encoder could follow or any other courses his fantasy allows him to follow or that his personal emotions suggest he follows. The inferential operation can be placed at any step of the interpretation. His journey can go anywhere; however, ultimately, he must return to the starting point in order to go on with the next information given by the encoder. So there is:

a. An “obliged” inferential work to do in order to meet the intentions of the encoder who leaves some information implicit but recoverable. The decoder must therefore make an evaluation of the communicative situation.

b. A “free” inferential work, on condition that the inferences are congruent with semantic and encyclopaedic principles.

c. A “corrective” operation by the decoder on the basis of the information he receives. As a matter of fact, at every step the encoder, has the option of following a different course. The decoder must then adjust his journey in order to be on the same track as the encoder.

d. And finally, if the communication is oral, a possible “reaction with a comment” on the standpoints and statements made by the encoder, and even coming up with a possible proposal or counterproposal and therefore entering the discussion now as a protagonist.

3. The behaviour rules

We can then formulate some behaviour rules for the decoder of an argumentative or narrative text:

1. Give the situation suggested by the encoder, a shape according to your fantasy, imagination, or preferences, but on the condition that congruency is maintained.

2. Interpret the situation and fill the missing information gaps, which you are able to reconstruct, as much as you want and according to the time span that is given.

3. Follow your general knowledge of the world, and especially the kind the encoder has.

4. Be prepared to stop with the inferential work you are doing in order to recover possible worlds from the elements you have been given.

5. Also be prepared to drop the results of your inferential work as soon as other alternatives are presented as the communication proceeds.

6. Create your own story or reasoning and wait until the encoder brings you back to the right course i.e. the course he (the encoder) prefers or chooses.

7. At each new step, repeat the same operation always with the expectation that things will go differently from the way you imagined they were supposed to go. But enjoy your

personal journey

8. In case of oral communication you might wish to take the opportunity to negotiate possible trips and journeys.

Of course as long as the decoder proceeds forward in the communicative situation, either argumentative or narrative, he gets closer to the route the encoder has chosen. Nevertheless he must expect that in case of a narrative text the plot will be surprisingly different from the one he imagined, or preferred, based on his own world or imagination.

Actually, this is less true for the argumentative text, which leaves less freedom in reconstruction or imagination but requires strict deductive work. As already mentioned, arguments are often suggested or must be found or imagined. The latter corresponds to one of the strategies of the encoder that of not revealing it, nor providing his own justification for it in order to avoid counter-argumentative moves making sure, however, that his statements will be accepted and will be taken as true. On the other hand in the argumentative course the decoder can think about filling additional arguments, or possibly counter-arguments, or stating doubts about the truth or the convincing force that the encoder’s statements have. In oral communication, after his inferential work, the decoder must enter the debate as an antagonist.

If in oral communication the decoder does not react, the encoder needs to adjust his message to make it more explicit. In argumentative communication the reaction by the decoder is stricter and more compulsory than is required in the telling of a story. Let us take the reaction to an observation made in the novel Life with Jeeves (Wodehouse, P.G. 1981, p.195) by the character Jeeves.

(10a) You say that this vase is not in harmony with the appointments of the room – whatever that means, if anything. I deny this, Jeeves, in toto. I like this vase. I call it decorative, striking, and, in all, an exceedingly good fifteen bobs worth”.

“Very good sir”.

The counter-argument against Jeeves standpoint is then that the vase is decorative and striking. The character then, without a real counterargument, goes on providing more information about his reasoning:

(10b) On the previous afternoon, while sauntering along the strand, I had found myself wedged into one of those sort of alcove places where fellows with voices like fog-horns stand all day selling things by auction. And, though I was still vague as to how exactly it had happened, I had somehow become the possessor of a large china vase with crimson dragons on it….

I liked the thing. It was bright and cheerful. It caught the eye. And that was why, when Jeeves, wincing a bit, had weighed in with some perfectly gratuitous art-criticism, I ticked him off with no little vim. Ne sutor ultra whatever-it-is, I would have said to him, if I’d thought of it. I mean to say, where does a valet get off, censoring vases? Does it fall within his province to knock the young master’s chinaware? Absolutely not, and so I told him.

The second part (10b) of the text is not addressed to the character Jeeves, anymore, but to the reader who has to evaluate the reasoning without having the opportunity to react to the character that is telling the story and giving his justifications laden with fallacy.

4. What is argumentation?

Now the question is: is argumentation a kind of reasoning, which allows on the grounds of some data to make inferences? Or is it a procedure for resolving a dispute in order to establish an agreement between two parties in relation to the truth of a standpoint?

In my opinion, argumentation is not only a matter of a contrast and of basic disagreement between two speakers. Rather it is the inferential work intended to establish the possible truth about standpoints. Inferential work constitutes the real procedure of reasoning, that which establishes on the ground of warrants a relationship between two statements. In other words, the issue is that inferential work is not just a matter of resolving differences of opinion but primarily that of the seeking the truth based on possible arguments. According to the ideal pragma-dialectical model of a critical discussion, argumentation (F.H. van Eeemeren, P. Houtlosser & F. Snoeck Henkemans 2007, p.4 and F.H. van Eemeren 2009) is supposed to resolve disputes. I believe that argumentation is intended to resolve the problem of stating and finding the truth, with or without dispute. The capacity of reconstructing, or completing a message and of developing a text is at the base of communication. Every speaker must be able to carry out inferential work since no message is so complete that no filling in on the part of the addressee is needed. Nevertheless, even if we agree that argumentation is a procedure to resolve a dispute, inferential competence is ultimately needed in order to complete the message, to understand the premises of a standpoint, to trigger conclusions from statements or to find out arguments in favour or against a standpoint. Unsaid or implicit messages, as a matter of fact, play a major role even in the critical discussion meant to resolve a dispute.

5. The impatient addressee

But is every decoder capable to make inferences? And how far does he go with his inferential work? There can be a passive decoder. But there can be an impatient decoder or discussion partner, or antagonist who reacts immediately, anticipating information with his inferential activity. If the impatient decoder/partner fills in information or anticipates conclusions, or brings about arguments on his own, he gives the encoder/partner the freedom to agree with or explore other alternatives or to correct the decoder in order to bring him back to the right course, to the encoder’s course. But with his arguments or his conclusions, the decoder at the same time prevents message completion quite a bit not allowing the encoder to complete his message and reasoning. Imagine the following dialog with an impatient addressee:

(11)

A: my passport …

B: did you lose it?

A: no, I ….

B: did you leave it at the hotel?

A: no when I was in the post office…

B: you were robbed, I know! A young man stood behind you…

A: no I know the boy, he is a good guy

B: then ….

A: wait a minute and let me finish my sentence,

B: I listen

A: when I was in the post office I showed it to the employee who told me that the passport is expiring and therefore I must ….

The impatient decoder made a number of inferences without allowing the other party to complete his thought and finish the sentence. I.e. he imagined that A was missing his passport and that he had to find possible reasons or arguments for the missing object. All reasons were plausible but did not correspond to the truth. Many political debates, especially in countries such as Italy, are conducted in this way: all participants are impatient decoders and aggressive encoders!!! Each decoder follows his own personalized course or script. As a result there are as many texts as there are addressees and visions of the world. Interacting is a way of negotiating the course to be followed among all the millions of possible courses (Eco 1994) that could be chosen from the given data. The inferential and reconstructive work by the addressee, depends on the way objects, statements, expressions are presented. Whether they are given the absolute truth, or whether they are questionable, or semi-assertive expressions (marked by indicators such as it goes without saying that), etc. Consider for instance the arguments mentioned in the following text (Wodehouse, P.G. 1981, pp.188-189)

(12) The Right Hon now turned to another aspect of the matter.

“I cannot understand how my boat, which I fastened securely to the stump of a willow-tree, can have drifted away.”

“Dashed mysterious”.

“I begin to suspect that it was deliberately set loose by some mischievous person”.

“Oh, I say, no hardly likely, that. You’d have seen them doing it”.

“No, Mr Wooster. For the bushes form an effective screen. Moreover, rendered drowsy by the unusual warmth of the afternoon, I dozed off for some little time almost immediately I reached the island”.

This wasn’t the sort of thing I wanted his mind dwelling on, so I changed the subject.

The decoder is free to fill in all the information which is not implied, not presupposed but which can nevertheless help complete the scenario, the context. Therefore he can add: events, situations, or argumentative information, which are not there, but that are necessary for his fantasy and completeness of vision in order to personalize the message and experience it. Very often, in carrying out this task, the combination of different stages, i.e. between obliged or free stages, inevitably takes place and the boundaries between what is required and what is invented and personal, remains for the most part rather vague. Each event, situation, description, statement, argument can be the start point for the emotional chain it generates. Additional instruction for the inferential work could be then the following:

1. Analyse the sequence, establish if it is an event or a situation and fill in the missing information about the conditions the event is taking place in: protagonists, location, and so on.

2. Try to imagine on the ground of the preceding information what is about to happen.

The story always moves forward. The decoder could of course reflect upon the last event and reconstruct possible causes or reasons, which determined the event or think about the course the event is now about to take or may follow as the story progresses.

6. Inferential competence

Every speaker possesses inferential competence, is capable of reconstructing and imagining a possible textual journey. For this, at least a basic reconstructive competence is required. The decoder also possesses inferential competence, which allows him to construct other worlds, based on personal preferences, emotions, and interests. Exercising the competence is optional and depends on a number of socially, culturally and emotionally related factors.

Not only the logical inferential ability but also the historical cultural background, allows the addressee to imagine possible interpretations and/or possible narrative or argumentative evolution. In the interpreting procedure, syntactic/semantic/textual/visual knowledge is required. Above all, textual competence allows the possibility to simultaneously carrying on with message decoding including the hidden message, or with inventing a continuation, as well as with assessing the encoder’s reaction, and recovering the needed adjustments[ii].

7. The linguistic influence

But, besides the encyclopaedic and pragmatic congruency principles and constraints, let us take into consideration the linguistic constraints the inferential work imposes

7.1 Textual argumentative constraints

When a starting point is a connective, then the inferential choice is obligatory in the sense that an expression must be formulated which fits with the function that the indicator requires. Thus if the indicator is something like “I believe that” then the choice must be made between the possible statements which can function as arguments or as claims adapting it to the preceding information. If the connective is for instance “unless” then a rebuttal that is adequate for the argument given but contrary to it, must follow. If an argumentative indicator has been used (introducing a claim or an argument, or a rebuttal, or an alternative, such as: therefore, because, since, although, nevertheless and so on), then the inference must contain a text which is congruent with the function indicated by the indicator. If the function of the sentence is complete and its function clear, then the decoder can proceed with completing the argumentative profile. If a standpoint is presented, he has to search possible arguments. If on the contrary an argument is presented then in that case he has to make an evaluation, to formulate a conclusion and/or to search possible additional arguments, or counterarguments (rebuttals, alternatives, reinforcements, specifications, and so on).

7.2. Language constraints

A constraint is also delivered by the type of language used by the encoder and the decoder. There are languages which give the most important information at the end of the sentence. For an Italian who receives the tensed verb immediately, there is the possibility to immediately start with his inferential work, and guessing which nominal is involved. In the case of the Italian verb: si scatenò (it broke out) we are able to imagine a discussione (a discussion) but also a tempesta (a thunderstorm). This is much easier than for a German speaker who has to wait till the end of the sentence to receive the main verb and thus to know something of the kind of event the sentence is about.

In Japanese time is marked by two morphological forms (ta or iru), but the forms are mentioned only at the end of the sentence. Therefore, the decoder must wait for the message to end in order to know when to place the story and hence to be able to start with his inferential work.

7.3. Lexical and syntactic constraints

Lexical collocations have a special position, a position which determines the inferential activity. In Italian, for example, the adjectives are often post nominal. It is, therefore, easier to guess which adjective follows a noun than to guess which noun follows an adjective as in German or other similar languages, where adjectives are always pre nominal.

An Italian term such as discussione can be associated with a small number of adjectives, whereas an adjective as vivace (heated, lively) has a number of options of nouns following it.

If one reads or hears a noun it immediately triggers the appropriate collocation: an adjective or a verb.[iii] The problem is different if we compare languages. If an Italian speaker says:

(13) ha cominciato a tagliare … (he started to cut …)

the decoder can think about pane (bread), erba (grass), capelli (hair), palla (ball),while in English the corresponding

(14) he started to cut….

can trigger bread or hair or ?grass but not *ball. If, on the contrary, an English speaker says

(15) he began to put a spin on…

then the decoder can only think of a ball. While if the encoder says

(16) he began to slice…

then one should most likely infer that the slicing is related to bread, roasted meat, but not *grass, while

(17) he began to reap…

would call to mind a crop before harvest time

8. Conclusion

To conclude, if in a possible world W it is true that there is a sentence p, then there are possible standard sentences that can follow this one, representing events, situations or arguments of the type q or f or g, etc, such that:

p -> q/f/g, etc. The decoder thus, anticipating the steps and the course the encoder is about to follow, must make a choice among the following options: q or f, or g and so on, on the basis of:

– a probability calculus;

– the kind of information, which in that specific case is in focus;

– the linguistic constraints in the textual profile he is interpreting and therefore, accordingly, choosing the appropriate collocation or idiomatic sequence;

– the opportunity, or preference he has, at the condition that syntactic, semantic, encyclopaedic congruency principles are met;

– an evaluation of the intentions of the encoder;

– his findings about which courses he is allowed to follow on the basis of syntactic, semantic encyclopaedic principles, but also on the basis of his preferences at that particular moment. The emotive status is of extreme importance!

– the textual and phrasal constraints that the type of language chosen impose. The condition for instance that the lexicon imposes since the language behaves as it does because it is made of formulas and not of free combinations;

– the opportunity to react and to take over the discussion as encoder and protagonist.

This is a hard but wonderful journey, a marvellous path, which helps both the decoder and the addressee at each and every moment to create and experience possible or invented worlds.

NOTES

[i] I am very grateful to Mrs I.A. Walbaum Robinson of the University of Roma TRE for very useful comments made on English language usage. I am also indebted to the unknown Reviewers who helped to improve the article.

[ii] One of the inferential basic laws for the decoder is to go back each time, after taking a journey to the departure point, in order to go on interpreting the whole received text. There are always deviations from the main lines of the text, thus we can consider the journeys taken as a kind of sub-story, i.e. the continuation or extension of the story. The decoder is obliged to wake up from his dreams and to go on with the interpretation, picking it up from where he started his personal journey.

[iii] So by the English word discussion we can think of a verb as to take place, or adjectives as intense, serious. But in English those adjectives precede, so the inferential work will be based on the search of the appropriate noun (struggle, fight), since the adjectives are given and function as starting point. In Italian, since the noun precedes then the search and inferential work will be for the appropriate adjective (violenta or animata).

REFERENCES

Adelaar, M., & Lo Cascio, V. (1986). Temporal relation, localization and direction in discourse. In V. Lo Cascio & Vet, C. (Eds.). Temporal Structures in Sentence and Discourse (pp. 251-297), Dordrecht: Foris Publications.

Christie, A. (1971). The mystery of the blue train, New York: Pocket Books.

Eco, U. (1994). Sei passeggiate nei boschi narrativi, Milano: Bompiani.

Eemeren, F. van, P. Houtlosser, & Snoeck Henkemans, F. (2007). Argumentative Indicators in Discourse: a Pragma-Dialectical Study, Dordrecht: Springer.

Eemeren, F. van, (2009). Strategic Maneuvering in Argumentative Discourse, Amsterdam: J. Benjamins.

Gardner, H. (2004). Changing Minds: The Art and Science of Changing Our Own and Other People’s Minds, Harvard Business School Press.

Lo Cascio, V., & Vet, C. (Eds.) (1986). Temporal Structures in Sentence and Discourse, Dordrecht: Foris Publications.

Lo Cascio, V. (1995). The relation between tense and aspect in Romance and other Languages. In P.M. Bertinetto, V. Bianchi, I. Higginbotham, M. Scartini (Eds.). Temporal Reference, Aspect and Actionality (pp. 273-293), Torino: Rosenberg & Sellier.

Lo Cascio, V. (2003). On the relationship between argumentation and narration. In F. H. van Eemeren, J. A. Blair, C. A. Willard and A. F. Snoeck Henkemans (Eds.)

Proceedings of the Fifth Conference of the International Society for the Study of Argumentation (pp. 695-700), Amsterdam: Sic Sat.

Lo Cascio, V. (2009). Persuadere e Convincere Oggi: Nuovo manuale dell’argomentazione, Milano: Academia Universa Press.

Moore, B. (1996). The Statement, London: Bloomsbury.

Plantin, C. (1998). La raison des émotions. In M. Bondi (Ed.). Forms of Argumentative Discourse. Per un’analisi linguistica dell’argomentare (pp. 3-50), Bologna: Clueb.

Wodehouse, P.G. (1981). Life with Jeeves, London: Pinguin Books