ISSA Proceedings 2010 – Strategic Maneuvering With The Technique Of Dissociation In International Mediation

1. Introduction

1. Introduction

This paper [i] is an illustration of the way in which dissociation becomes a tool of the mediator’s strategic maneuvering, by means of which the disputants’ disagreement space is minimized, decision-making being thus facilitated. The mediator’s argumentative behavior will be explored, investigating the way in which he succeeds in “maintaining a delicate balance” (van Eemeren & Houtlosser 2002) between the dialectical and the rhetorical aims in employing the argumentative technique of dissociation.

As established by van Rees (2006, 2009a), dissociation implies the use of two speech acts – definition and distinction. The analysis conducted in this paper shows the way in which dissociation is employed in the mediated type of discourse with the purpose of defining (and re-defining) ‘peace’ and the conditions of a peace agreement, ‘security’ or other important issues regarding the state of war, and of making a distinction, respectively, between the atrocities of war and the idea of peace. The aim is to strategically pursue both the rhetorical aspects – to achieve rhetorical effectiveness, in the sense of dissociation as bringing about a change in the starting point of the other party, and the dialectical ones – as all the parties want to resolve the conflict reasonably. Consequently, the discussion of the issues of peace and security perfectly shapes the relationship between dissociation and the speech acts of defining and distinguishing and proves how strategic maneuvering functions in real-life argumentation (cf. Muraru 2008c).

The context of international mediation under discussion is illustrated by the particular case in which the American president, Jimmy Carter, acted as a third party in the conflict between Egypt and Israel (1977, 1978, 1979), with the aim of contributing to a dispute resolution. As a result of the Camp David negotiations, two documents were signed (“A Framework for Peace in the Middle East Agreed at Camp David” and “A Framework for the Conclusion of a Peace Treaty between Egypt and Israel”) that prepared the ground for the Peace treaty, concluded on March 26, 1979.

2. Conceptual framework

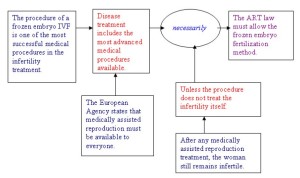

Dissociation is a theoretical concept first introduced by Chaïm Perelman and Lucie Olbrechts-Tyteca in The New Rhetoric (1969), being treated, like its complementary part – association, as a scheme that characterizes “all original philosophical thought” (p. 190). Therefore, dissociation is viewed as an argumentative scheme, which implies the splitting up of a unitary concept, such as ‘law’, into two other different concepts: ‘the letter of the law’ and ‘the spirit of the law’. Due to the ambiguity of argumentative situations, the main function of dissociation is to “remove an incompatibility” and to prevent an incompatibility from occurring, “by remodeling our conception of reality” (Perelman & Olbrechts-Tyteca 1969, p. 413).

The dissociation of notions implies a certain change in the conceptual data at the basis of argument, which entails a modification of the “very structure” of the respective independent elements. Thus, the notion of philosophical pairs is introduced, the pair “appearance – reality” being considered prototypical for conceptual dissociation, due to the multiple incompatibilities that exist between appearances. The two concepts that make up the philosophical pair are called term I (“appearance”) and term II (“reality”). Term II can only be defined in relation to term I, being both “normative and explanatory”; it is a “construction”, and not “simply a datum”, establishing, during the dissociation of term I, a rule function of which the multiple aspects of term I are organized in a hierarchy. The fact that term II provides a criterion, a norm, enables judgment-making with regard to the presence or lack of value of the aspects of term I. Therefore, in term II, “reality and value are closely linked” (Perelman & Olbrechts-Tyteca 1969, p. 417).

Departing from this approach but also drawing on it, M. A. van Rees shifts the perspective of analysis from mainly rhetorical to mainly dialectical view, investigating its various uses as a technique of strategic maneuvering employed in practical discussions. In this type of approach, van Rees in line with other authors (Grootendorst 1999, Gâţă 2007) brings evidence against the treatment of dissociation as an argumentative scheme (Perelman & Olbrechts-Tyteca 1969), viewing it as a technique that helps at solving a difference of opinion, and whose “argumentative potential is based on the fact that the two concepts resulting from the separation of the original notion are portrayed as non-equivalent: the one is represented as more important or more essential than the other” (van Rees 2005a, p. 383). Consequently, dissociation involves a unitary concept expressed by a single term that is split up in two different concepts of unequal value. One of them becomes a completely new term, the other either preserves the aspects of the original term, being redefined, or becomes itself a new term, as well, with its own definition, thus the original term being given up (cf. van Rees 2009a, p. 9).

Gâţă (2007) brings an important contribution to the study of dissociation by the new theoretical model she suggests, introducing the “constitutive moves” (p. 441) on the basis of which the use of dissociation as a way of strategic maneuvering can be better accounted for. This technique “allows the speaker to deconstruct / disassemble a notion by distinguishing some of its particular aspects which are then reordered and re-constructed / re-structured / re-assembled into two new notions”, the terms “deconstruct” / “disassemble” corresponding to distinction, the first component of dissociation, and “re-constructed” / “re-structured” / “re-assembled” corresponding to definition, the second component of dissociation (Gâţă 2007, p. 441)[ii]. In Gâţă’s view (2007), dissociation allows the speaker to de-construct and then re-construct notions by generating or by giving the illusion to create (fresh and new) knowledge and by thus redefining and / or modifying the audience’s and / or the opponent’s experience of the world.

Dissociation is “a powerful instrument to clarify discussions and to structure our conception of reality”, due to the two speech acts that it implies (van Rees 2005a, p. 391), distinction and definition, which belong to the category of what van Eemeren and Grootendorst (1984) call ‘usage declaratives’. This function of clarifying concepts and resolving contradictions generates its potential for ensuring the balance between dialectical reasonableness and rhetorical effectiveness, implied by strategic maneuvering, in the various stages of a critical discussion. Van Rees (2006) discusses the specific dialectical moves in which dissociation can be used, as well as the rhetorical effects of using dissociation in these moves[iii]. Gâţă also states that dissociation can be considered a way of strategic maneuvering which occurs in the confrontation or argumentation stages of a critical discussion and which gets the discussion back to the opening stage. Thus, in introducing a dissociation, the protagonist of a standpoint can select from the topical potential available a notion which he perceives as contradictory, redefining it, precizating[iv] or reterming it, by adapting to the audience’s horizon of expectations. At the same time, he can employ the most appropriate rhetorical devices to enable him to define or reformulate the respective notion in such a way as to best support his standpoint.

3. International mediation as an argumentative activity type

The characterization of mediation from a linguistic perspective with focus on the argumentative dimension is possible only by viewing mediation as a specific type of practice, unfolding in a particular setting, and having certain players. In this sense, as a communicative activity type taking place in an institutionalized setting, mediation is a form of institutional talk, involving certain “goal orientations”, “special and particular constraints on what one or both participants will treat as allowable contributions”, and being associated with “inferential frameworks and procedures” (Drew & Heritage 1992, p. 22). Conflict arises from the inevitable differences that exist between the goals pursued by the institutional participants.

Mediation designates a “cluster of activity types” (van Eemeren & Houtlosser 2009, p. 8) that start from a difference of opinion which has turned into a disagreement, impossible to be resolved by the parties themselves. Consequently, the disputants have to resort to a third party, who, acting as a neutral facilitator of the discussion process, guides the parties in their more or less cooperative search for a solution. The general picture of international mediation promotes the image of the mediator as a central figure, who tries to bring a change in the “behavior, choice and perceptions” (Bercovitch 1991, p. 4) of the participants in the conflict, by exercising his influence over the dispute. By interacting with each disputant separately, and with both together, the mediator “becomes in effect another negotiating part, an extension of the conflict system” (ibid.).

As argued elsewhere (Muraru 2009b), international or diplomatic mediation, in particular, may be regarded as a rather moderately institutionalized activity type[v], due to the diplomatic relations and practices the parties are engaged in, the disputants being guided by some fixed sets of values and particular norms of behavior, which are culturally bound.

By definition, mediation needs three parties that can reach the phase of negotiation: – the two conflicting parties have, in turn, the roles of protagonist and antagonist of a standpoint, while the third party – the mediator – as a co-arguer, addresses either each of the parties, thus putting forth the position of the opposing party, or both parties, as a common audience. First, the mediator negotiates with each of the disputants in private, and, eventually, the parties get engaged in the negotiation process by themselves. More precisely, as a facilitator of communication, the mediator has the role of helping the parties to agree on reaching the negotiating phase (Muraru 2008b, p. 808).

Mediation is an example of an argumentative activity type in which strategic maneuvering manifests itself. Although the mediator’s main function is to structure and to improve the communication between the parties, in argumentative practice, “his strategic maneuvering is often directed at overcoming the institutional constraints and contributing to the effectuation of an arrangement” (van Eemeren & Houtlosser 2005, p. 81). In order to determine the parties to come to an agreement, the mediator’s role is to clearly reframe the parties’ positions with respect to the divergent issues, and formulate and reformulate the standpoints and starting points advanced by the two conflicting parties. The mediator’s task is “to clarify what the disputants are arguing and to project alternative trajectories for the discussion” rather than “argue for or against disputant standpoints or tell disputants what to argue” (van Eemeren et al. 1993, p. 120). In this sense, the mediator displays a “co-argumentative” behavior (Greco Morasso 2007, p. 513), his main task being to help the parties to reasonably find a solution to their difference of opinion, which they could not solve by themselves.

Starting from the three-fold classification of mediator roles into communicator, formulator and manipulator, suggested by Touval and Zartman (1985), a characterization of the mediator as a multiple role-player has been made (Muraru forthcoming), on the basis of which I have identified two argumentative dimensions of the mediator – facilitative[vi] and manipulative (in the sense of contributing to conflict resolution)[vii]. Considering this, the discourse of mediation is viewed as involving two types of relations in which argumentative roles shift (cf. Muraru 2008a, p. 2): (1) the two parties act, in turn, in the argumentative exchange, as protagonist and antagonist – each proposing his own definition of the divergent issues in accordance with the corresponding system of values and believes; (2) there is the third party, acting, on the one hand, as a ‘pure’ mediator, in the sense of facilitating the parties’ decision-making, through the roles of formulator and communicator, and, on the other hand, as a negotiator, who resorts to manipulation, in the sense that, he, sometimes tries to force an outcome and sets the things towards imposing a resolution. Each of the three parties strategically maneuvers linguistic and extralinguistic situations, in the sense of resorting to the three elements of topical potential, audience orientation and presentational devices.

4. Dissociation as a tool of the mediator’s strategic maneuvering

Since the focus of this paper is the mediator’s linguistic behavior, particularly the way in which he succeeds in strategically maneuvering the parties, the situation and the issues, the text under analysis belongs to the mediator’s discourse. It is meant to illustrate the way in which Jimmy Carter reformulates the starting points of the discussion with respect to the two parties, and how dissociation is employed with the aim of convincing the parties to put an end to the conflict.

It is the moment after the Camp David negotiations, September 18, 1978, when President Carter addresses the Congress, after two agreements have been signed[viii]. Therefore, the role of his intervention is to mark the end of a negotiation phase, and to clearly delineate the results of the Camp David agreements. To this particular aim, the arguer strategically makes use of the techniques of dissociation in reformulating positions. Thus, at this concluding stage, dissociation is meant to give a precization of the partial conclusion that has been reached (van Rees 2005b, p. 45), this technique being employed with the strategic purpose of highlighting a favorable outcome, in which the mediator has played a crucial part.

(1) Through the long years of conflict, four main issues have divided the parties involved. One is the nature of peace— whether peace will simply mean that the guns are silenced, that the bombs no longer fall, that the tanks cease to roll, or whether it will mean that the nations of the Middle East can deal with each other as neighbors and as equals and as friends, with a full range of diplomatic and cultural and economic and human relations between them. That’s been the basic question. The Camp David agreement has defined such relationships, I’m glad to announce to you, between Israel and Egypt.

(2) The second main issue is providing for the security of all parties involved, including, of course, our friends, the Israelis, so that none of them need fear attack or military threats from one another. When implemented, the Camp David agreement, I’m glad to announce to you, will provide for such mutual security.

(3) Third is the question of agreement on secure and recognized boundaries, the end of military occupation, and the granting of self-government or else the return to other nations of territories which have been occupied by Israel since the 1967 conflict. The Camp David agreement, I’m glad to announce to you, provides for the realization of all these goals.

(4) And finally, there is the painful human question of the fate of the Palestinians who live or who have lived in these disputed regions. The Camp David agreement guarantees that the Palestinian people may participate in the resolution of the Palestinian problem in all its aspects, a commitment that Israel has made in writing and which is supported and appreciated, I’m sure, by all the world.

(5) Over the last 18 months, there has been, of course, some progress on these issues. Egypt and Israel came close to agreeing about the first issue, the nature of peace. They then saw that the second and third issues, that is, withdrawal and security, were intimately connected, closely entwined. But fundamental divisions, still remained in other areas—about the fate of the Palestinians, the future of theWest Bank and Gaza, and the future of Israeli settlements in occupied Arab territories. […]

(6) While both parties are in total agreement on all the goals that I have just described to you, there is one issue on which agreement has not yet been reached. Egypt states that agreement to remove the Israeli settlements from Egyptian territory is a prerequisite to a peace treaty. Israel says that the issue of the Israeli settlements should be resolved during the peace negotiations themselves. […]

(7) But we must also not forget the magnitude of the obstacles that still remain. The summit exceeded our highest expectations, but we know that it left many difficult issues which are still to be resolved. These issues will require careful negotiation in the months to come. The Egyptian and Israeli people must recognize the tangible benefits that peace will bring and support the decisions their leaders have made, so that a secure and a peaceful future can be achieved for them.

(September 18, 1978, pp. 1534-36)

In his capacity of a co-arguer (drawing on Greco Morasso’s (2007) view that the mediator displays a co-argumentative behavior), the mediator’s task at the concluding stage is to establish the results of the negotiations and to supervise the way in which the two disputants agree on the tenability of the respective standpoint (cf. van Rees 2009a, p. 78).

Carter begins by re-stating the issues that underlie the conflict situation: both stressing the points on which some kind of agreement has been reached, and outlining the elements of disagreement, which are still the subject of further negotiations. The issues are introduced by means of dissociations, by implicitly performing the speech acts of distinction and definition. The “nature of peace” (par. 1) is the top priority among the various divergent issues, always (in all of Carter’s interventions) being mentioned first, since the resolution of several of the other problems both derives from and is dependent on achieving peace. Thus, Carter dissociates between the notion of ‘peace’ implicitly defined (by employing the verb “mean”), as the cessation of war (term I) on the one hand, and as a state where harmonious diplomatic relationships develop (term II), on the other. The mediator obviously promotes term II as the norm, valuing the “range of diplomatic and cultural and economic and human relations” higher than term I, which is negatively valued due to the presence of the adverbial element “simply” (“peace will simply mean”). In this way, Carter’s attempt is to introduce a notion of real peace, thus creating an explanation and a norm that the peace should satisfy. In Konishi’s (2003, pp. 638-639) interpretation, term I designates the ‘apparent peace’, represented by the lack of war, and term II the ‘real peace’, represented by the harmonious coexistence of all the states in the Middle East.

The same analysis is conducted with regard to the other issues. “Security of all parties involved” or “mutual security” represents the norm and is dissociated from the concept of security defined as the mere lack of fear of “attack or military threats” (par. 2). Closely linked to the idea of security is the problem of border delineation (par. 3): whether “secure and recognized boundaries” are the result of the granting of self-government or of the withdrawal of Israel to the borders before the 1967 conflict. Carter himself stresses the elements of progress (par. 5) implicitly suggesting the role the American intervention has played, by particularly emphasizing the element of time (“over the last 18 months”), at the same time, progress being introduced as self-evident (“of course”).

Departing from the profile of the mediator who typically seeks agreement by leaving aside or ‘postponing’ the issues that are less likely to be solved, Carter’s ambition is to shed light on all the divergent issues that nurture the conflict situation. Thus, he is aware that a true resolution is possible only if the most ardent problem is to be clarified – “the painful human question of the fate of the Palestinians” (par. 4). Though not explicitly introducing a dissociation, it can be easily inferred from his words that he distinguishes between two categories of Palestinians: the ones ‘who live’, and the ones ‘who have lived’ in these disputed regions. Dealing with such a delicate issue, and considering the contrasting views of the disputing parties on this matter, the mediator, in compliance with his strategic role, maintains a neutral attitude, thus placing each of the two categories of Palestinians outside the category of simple Palestinians, each of them being more highly valued by the Arabs or by the Israelis.

Unlike the first three issues on which agreement has been reached, whose progress has been emphasized by Carter by means of the reiterative sentence “I’m glad to announce to you”, the Palestinian problem still remains a point of disagreement, a fact signaled at the level of language by the use of the modal ‘may’ expressing permission (par. 4). The effect of the use of ‘may’ is strategically counterbalanced by the strong commissive ‘guarantees’. The larger context of this dispute is characterized by a change in the Israeli position with regard to the acceptance of the Palestinians at the negotiating sessions, as opposed to the initial attitude of total rejection of this matter. In this sense, President Carter particularly emphasizes the commitment on the part of Israel (par. 4). Again the use of “I’m sure” introduces his viewpoint as universally accepted, preventing the audience from casting any doubt on it.

Another issue upon which “agreement has not yet been reached” (par. 6) is the removal of the Israeli settlements. The reformulation of the parties’ standpoints with reference to this matter is realized by means of indirect speech: “Egypt states…”, “Israel says…”, in this way trying to preserve as much as possible from the original version of the disputants. Thus, Egypt refuses to enter negotiations without the Israelis’ acceptance to remove the settlements, while Israel refrains from committing itself to any kind of action with respect to this issue.

Although the areas of agreement are recurrently stressed – “there has been, of course, some progress” (par. 5), “both parties are in total agreement” (par. 6), “The summit exceeded our highest expectations” (par. 7), we infer from investigating the text that Carter attributes a crucial role to the elements of disagreement. These are restated by enumeration (par. 5), and reiterated and overemphasized (par. 7) with the aim of maintaining the parties’ active interest in the divergent issues. His assertive (“we must also not forget”) can be reinterpreted as a directive by means of which Carter suggests that these issues should be dealt with as a matter of “urgency”. The same illocutionary force is conveyed by the meaning of the structure “the magnitude of the obstacles” (par. 7). Carter ends by encouraging the negotiations between the parties, stressing once more “the tangible benefits” of achieving peace.

Considering the fact that dissociation can be used “to negotiate inherent tensions in a critical discussion” (Gâţă 2007, p. 441), and that one of its constitutive moves is concession-making, the mediator uses this technique to reformulate the parties’ standpoints and starting points with the aim of eliciting some compromise and of suggesting solutions for agreement[ix]. Carter also brings along his preference for one position or the other when he chooses to maintain the particular viewpoint of a party by attributing it a normative value, or treating it as the standard position (for instance, when he introduces his own view that the settlements should be withdrawn)[x]. However, most of the times, the mediator chooses to advance a new definition of a particular issue, both preserving some of the initial information from the parties’ way of conceiving of the respective problem, and adding some fresh details, so that the newly-defined issue has gained new nuances as a result of dissociation. Also, in reformulating or rephrasing the position of a party, the mediator may clarify or enrich the stated position (cf. Arminen 2005, pp. 193-4). In this way, he contributes to reshaping positions closer to an agreement, which implies that the divergent issues can be more easily dealt with, and the new formula becomes more acceptable, thus both parties being more prone to concessions, due to the face-saving mechanism that the mediator promotes.

I believe that this first stage of concluding can be ascribed a double interpretation. On the one hand, it illustrates Gâţă’s view that, at this stage, dissociation may generate either a side-discussion, or a discussion with a different standpoint from the initial one, which has already been agreed upon (Gâţă 2007, p. 442). On the other hand, dissociation is employed with the purpose of convincing the larger audience that the commitments expressed in the beginning have been at least maintained if not totally fulfilled.

In this particular diplomatic context, the issues which have found no solution become the initial standpoints of the repeated side-discussions at a micro level, which are treated as parts of a Macro critical discussion (cf. Muraru 2009a). Therefore, this first phase of concluding has only established the points of agreement under a written form, the decisive phase being that of implementation of the provisions in the written documents, and concluding the Peace Treaty. In addition, I consider that the instance of international mediation analyzed here consists of several side-discussions, in which the starting points have repeatedly changed and on which agreement has eventually been reached by the opponents, the results being used in the main discussion. Thus, dissociation is regarded as dialectically sound, as both the procedural and the material requirements have been met. Functioning as a filter, the mediator is the party “in the middle” who puts the change in starting points up for discussion, on behalf of each party, which, by means of compromise solutions, eventually accept the change.

Treated as an inherent part of the mediator’s strategic maneuvering, the technique of dissociation has contributed, both dialectically and rhetorically, to the resolution of the dispute. The dialectical contribution refers to the way in which Carter has provided a more precise interpretation of the standpoints, which the opponents have considered as tenable, the mediator also establishing and clarifying, by resorting to usage declaratives (i.e., defining), the results of the discussion. The rhetorical effect is that Carter has chosen the interpretation of the conclusion that serves his interest best, formulating it accordingly. For example, Carter’s commitments in the opening stage included the Palestinian question, as well. In the concluding stage, dissociation has served as a means “to evade unwelcome consequences” (van Rees 2009a, p. 88), thus Carter succeeding in escaping the unfavorable implications that a failure in solving the Palestinian issue would entail. From exploring the text, one can easily see that the emphasis on the elements of progress particularly help the mediator to present the situation in a favorable light, making use of specific markers which enable him to rule out any further argument.

Consequently, by strategically maneuvering both the process and the content of mediation, the mediator has succeeded in reshaping positions so that they would fit both the parties’ understanding and definition of the respective situation (cf. Arminen 2005, p. 170), and the mediator’s own conception of the particular reality underlying conflict.

5. Conclusion

The analysis of this fragment is an illustrative example of the use of dissociation as a major technique employed in the mediation context, in the sense that the disputants’ positions may be interpreted as the two terms which make up a dissociative structure. Both opponents seek peace, which implies goal compatibility, but they differ with respect to what peace entails, and to the means of pursuing this goal. Consequently, the mediator’s strategic role is to reconcile the two incompatible positions.

In the process of argumentation in an international conflict context, dissociation becomes a technique the mediator resorts to, in order to contribute to the resolution of the dispute. It is employed, in this particular case of international mediation, with the aim of solving the inconsistencies between the two conflicting parties – Egypt and Israel, serving the purpose of clarification and explanation of contextualized terms and concepts such as ‘peace’, ‘security’, or ‘territory’.

By making use of such an argumentative technique, the mediator has facilitated the parties’ decision-making, by succeeding in changing the starting points of their discussion (as can be seen in the reformulations of the terms in the peace treaties – the proposal and the final version), thus dialectically managing to solve the conflict. The use of definition and distinction as the speech acts involved by dissociation enhance the dialectical purpose of the concept of strategic maneuvering, employed with the purpose of clarifying positions, and ‘precizating’, since they belong to the category of usage declaratives. At the same time, the rhetorical effect is felt at the level of reformulations that imply redefinitions of the terms, which are presented without further argument, thus dissociation being introduced as self-evident. Moreover, rhetorically, (re)definitions contribute to establishing a case of partial or total consensus.

In the context of international mediation dissociation has an argumentative potential. It becomes the instrument by means of which the process of the parties’ strategic maneuvering is realized, with the aim of conflict resolution, both by arguing reasonably and by suggesting a solution that serves their interests best.

NOTES

[i] This study is financed by the Romanian Ministry of Education through the National Council of Scientific Research in the framework of PN II PCE ID 1209/2007 (Ideas) project.

[ii] Gâţă (2007) illustrates the way in which strategic maneuvering functions in practice by providing the analysis of some argumentative excerpts from a media electronic forum debate in French on whether Paris needs the Olympic Games in 2012.

[iii] As van Rees states, “dissociation my serve dialectical reasonableness by enabling the speaker to execute the various dialectical moves in the successive stages of a critical discussion with optimal clarity and precision”, and rhetorical effectiveness, because this technique enables the speaker to “present a particular state of affairs in a light that is favorable to the speaker’s interest” (2006, p. 474).

[iv] “Precization” is a term coined by Naess (1966) in interpreting formulations from a semantic point of view. Van Rees considers that precization contains “important aspects of what goes on in dissociation” (2009a, p.13), especially in relation to distinction, and, consequently, she has adopted it in her treatment of dissociation.

[v] In claiming that international mediation, in particular, can be viewed as a moderately institutionalized type of activity I am slightly diverging from van Eemeren and Houtlosser’s view (2005) who consider the general phenomenon of mediation as a weakly institutionalized activity type.

[vi] The role of facilitator that Carter assumes refers to ‘impartiality’ and ‘equidistance’ in offering the same view to both disputants, and making available the same resources to both. Therefore, fairness is the kind of behavior that leads to success, but also a behavior that is mutually acceptable to and accepted by the parties participating in the conflict, in the sense of ‘soundness’ of argumentation. In other words, it refers to the mediator ‘reasonably doing what is in the parties’ best interest’.

[vii] The idea of manipulation implied by Carter’s behavior is deprived of the negative connotation of the word, and it is seen as the rhetorical side entailed by strategic maneuvering. Therefore, the role of manipulator is interpreted as the role the mediator assumes when the conflict has reached a stalemate, thus enabling the mediator to put some pressure on the disputants, in order to move things towards a resolution path.

[viii] In Muraru 2009a, I have treated the particular instance of mediation as a Macro-critical discussion, providing an analysis of the four dialectical stages of the reconstructed mediation. Thus, I have established that the Macro-concluding stage is sub-divided into two sub-stages, the text under analysis in this paper, being part of the first sub-stage. This explains why the formulation of the divergent issues by the mediator tends to be judged as being part of the opening stage, since the issues become the starting points of another side-discussion.

[ix] Rewards, offers, concessions, and compromise solutions are considered “kinds of allowable contributions” (van Eemeren & Houtlosser 2007, p. 388) within the institutions of mediation and negotiation. Therefore, due to the fact that the various moves advanced by the parties under the form of specific speech acts are part of this argumentative activity type, they are not considered fallacious. Consequently, judged within the constraints imposed by the particular activity type of mediation, Carter’s behavior is evaluated as reasonable, since it proves to have contributed to the successfulness of the situation.

[x] Although most of the approaches to mediation envisage neutrality as the main characteristic of the ideal mediator, I consider that a mediator’s major achievement is that of generating a successful outcome. In this sense, successful mediation includes the mediator’s active direction and participation as he works with the disputants in a constructive way directed at defining the dispute and at generating solutions (Cobb and Rifkin 1991, p. 49). Therefore, a mediator needs to remain as neutral as possible only as long as this attitude essentially contributes to conflict resolution. If neutrality becomes a constraint on the mediator’s behavior, thus obstructing the decision-making process and forcing the mediator to deny his role in the construction and transformation of the conflict (ibid., p. 41), then, giving up neutrality is considered an allowable move.

REFERENCES

Public Papers of the Presidents: Jimmy Carter (1978) vol. II. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

Arminen, I. (2005). Institutional Interaction. Studies of Talk at Work. Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Company.

Bercovitch, J. (1991). International mediation. Journal of Peace Research 28 (1), 3-6.

Cobb, S., & Rifkin, J. (1991). Practice and paradox: Deconstructing neutrality in mediation. Law and Social Inquiry, 16, 35-62.

Drew, P,. & Heritage, J. (1992). Analyzing talk at work: an introduction. In P. Drew & J. Heritage (Eds.), Talk at Work: Interaction in Institutional Settings (pp. 3-65). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Eemeren, F. H. van, & Grootendorst, R. (1984). Speech Acts in Argumentative Discussions. Dordrecht/ Cinnaminson: Foris Publications.

Eemeren, F. H. van, & Houtlosser, P. (2002). Strategic maneuvering: Maintaining a delicate balance. In F. H. van Eemeren & P. Houtlosser (Eds.), Dialectic and rhetoric: The warp and woof of argumentation analysis (pp.131-159). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Eemeren, F. H. van, & Houtlosser, P. (2005). Theoretical construction and argumentative reality: An analytic model of critical discussion and conventionalised types of argumentative activity. In D. Hitchcock & D. Farr (Eds.), The Uses of Argument. Proceedings of the OSSA Conference (pp.75-84), Hamilton: McMaster University

Eemeren, F.H. van, & Houtlosser, P. (2007). Strategic maneuvering: A synthetic recapitulation. Argumentation, 20 (4): 381-392.

Eemeren, F. H. van, & Houtlosser, P. (2009). Seizing the occasion: Parameters for analysing ways of strategic manoeuvring. In F.H. van Eemeren & B. Garssen. (Eds.), Pondering on Problems of Argumentation: Twenty Essays on Theoretical Issues (pp. 3-14), Amsterdam: Springer.

Eemeren, F. H. van, Grootendorst R., Jackson S., & Jacobs S. (1993). Reconstructing Argumentative Discourse. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press.

Gâţă, A. (2007). Dissociation as a way of strategic maneuvering in an electronic forum debate. In F. H. van Eemeren, A. Blair, Ch. A. Willard, B. Garssen (Eds.), Proceedings of the Sixth Conference of the International Society for the Study of Argumentation, vol. I (pp. 441- 448), Amsterdam: Sic Sat.

Greco Morasso, S. (2007). The covert argumentativity of mediation: Developing argumentation through asking questions. In F.H. van Eemeren, A. Blair, Ch. A. Willard, B. Garssen (Eds.), Proceedings of the Sixth Conference of the International Society for the Study of Argumentation (pp. 513-520), Amsterdam: Sic Sat.

Grootendorst, R. (1999). Innocence by dissociation. A Pragma-dialectical analysis of the fallacy of incorrect dissociation in the Vatican document ‘We remember: A reflection on the Shoah’. In F.H. van Eemeren, R. Grootendorst, J.A. Blair, & Ch.A. Willard (Eds.), Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference of the International Society for the Study of Argumentation (pp. 286-289), Amsterdam: Sic Sat.

Konishi, T. (2003). Dissociation and its relation to the theory of argument. In F.H. van Eemeren, A. Blair, Ch. A. Willard, A F. Snoeck Henkemans (Eds.), Proceedings of the Fifth Conference of the International Society for the Study of Argumentation, vol. I (pp. 637-640), Amsterdam: Sic Sat.

Muraru, D. (2008a). The mediator’s strategic maneuvering in international mediation. In A. Gâţă & A. Dragan (Eds.), Communication and Argumentation in the Public Sphere, Vol. II, Issue 1 (pp. 1-11). Galaţi: Galaţi University Press.

Muraru, D. (2008b). The mediator as meaning negotiator. In G. Gobber, S. Cantarini, S. Cigada, M.C. Gatti & S. Gilardoni (Eds.), Proceedings of the IADA Workshop Word Meaning in Argumentative Dialogue. Homage to Sorin Stati. Volume II. L’analisi linguistica e letteraria XVI Special Issue 2 (pp. 807-820), Milano: EDUCatt.

Muraru, D. (2008c). Dissociation as a speech act in argumentation in international mediation. In Y. Catelly, F. Popa, D. Stoica, & B. Raileanu-Prepelita (Eds.), Proceedings of the Second International Conference Limbă, Cultură şi Civilizaţie în Contemporaneitate (pp. 275-282). Bucureşti: Politehnica Press.

Muraru D. (2009a). Reconstructing Jimmy Carter’s discourse as third-party intervention in the Middle East conflict. In A. Gâţă & A. Dragan (Eds.), Communication and Argumentation in the Public Sphere, Vol. III, Issue 2 (pp. 108-118). Galaţi: Galaţi University Press.

Muraru, D. (2009b). International mediation as an argumentative activity type. INTERSTUDIA, Cultural Spaces and Identities in (Inter)action (pp. 224-233). Bacău: Alma Mater.

Muraru, D. (forthcoming). The mediator as a multiple role-player. Paper presented at the third Conference Limbă, Cultură şi Civilizaţie – Noi căi spre succes, June 12-13 2009, Polytechnic University of Bucharest.

Naess, A. (1966). Communication and Argument. Elements of Applied Semantics. London: Allen & Unwin.

Perelman, Ch., & Olbrechts-Tyteca, L. (1969). The New Rhetoric. A Treatise on Argumentation, translated by J. Wilkinson & P. Weaver. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

Rees, M. A. van. (2002). Argumentative functions of dissociation in every-day discussions. In H.V. Hansen et al. (Eds.), Argumentation and its Applications. Proceedings of the Fifth OSSA Conference. CD-ROM. Windsor, Ontario: OSSA.

Rees, M. A. van. (2005a). Dialectical soundness of dissociation. In D. Hitchcock (Ed.), The Uses of Argument: Proceedings of a conference at McMaster University, 383-392, Ontario Society for the Study of Argumentation.

Rees, M. A. van. (2005b). Dissociation: A Dialogue Technique. Studies in Communication Sciences, Special Issue “Argumentation in Dialogic Interaction” (pp. 35-50).

Rees, M. A. van. (2006). Strategic Maneuvering with Dissociation. Argumentation, 20, 473-487.

Rees, M. A. van. (2009a). Dissociation in Argumentative Discussions. A Pragma-dialectical Perspective. Dordrecht: Springer.

Rees, M. A. van. (2009b). Dissociation: between rhetorical success and dialectical soundness. In F.H. van Eemeren & B. Garssen (Eds.), Pondering on Problems of Argumentation: Twenty Essays on Theoretical Issues (pp. 25-34), Amsterdam: Springer.

Touval, S., & Zartman W. (1985). International Mediation in Theory and Practice. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.