ISSA Proceedings 2010 – The Appeal To Ethos As A Strategic Maneuvering In Political Discourse

1. Introduction

1. Introduction

The aim of this paper is to analyze the appeal to ethos as a strategic maneuver in political argumentation. In section two I review ethos as an Aristotelian persuasive strategy and its two components according to Poggi (2005), i.e. competence and benevolence; in section three I focus on two of the possible ways in which one could convince the other of being competent and benevolent, i.e. either emphasizing his own qualities or highlighting the differences between himself and the opponent; in the fourth section I introduce the notion of dichotomy (Dascal 2008) and focus on the arguers’ possible tactical aims of presenting a mere opposition or contrast as a dichotomy. In the last two sections I briefly introduce the notion of strategic maneuvering and, while providing an example of a case of strategically maneuvering with ethos, I show how employing dichotomies can be seen as an aspect of the strategic maneuvering.

2. The appeal to ethos as a persuasive strategy in political discourse

According to Aristotle, the orator in persuading makes use of three different strategies, logos, pathos and ethos. If the orator tries to persuade the audience by making use of argumentation, then he is employing logos. If he manipulates instead the audience’s emotions, evoking the possibility for the audience to feel pleasant emotions or to prevent unpleasant ones, he is making use of the strategy of pathos. Finally, if the orator tries to persuade the audience by emphasizing his own moral attributes and competences, then he is making appeal to ethos. The appeal to ethos is, according to Aristotle, the most efficient strategy: ‘the orator’s character represents, so to say, the strongest argumentation’ (Retorica, I, 1356a). Poggi (2005) distinguishes two aspects of ethos: ethos-benevolence (the Persuader’s moral reliability – his being well-disposed towards the Persuadee, the fact that he does not want to hurt, to cheat, or to act in his own interest), and ethos-competence (his intellectual credibility, expertise, and capacity to achieve his goals, including possibly the goals of the Persuadee he wants to take care of). These two aspects are the two necessary components of trust and in order to be persuaded, the Persuadee has to believe that the Persuader possesses these two attributes.

Therefore, in order to elicit the audience’s trust the Persuader has to convince them, i.e. make them believe with a high level of certainty, that he is competent and benevolent at the same time. This is an important part of the Persuader’s self-presentation. To demonstrate one’s competence, one may enumerate one’s achievements; while to display benevolence, one may stress how one wants the audience’s welfare. For example, as pointed out by Poggi & Vincze (2008), Romano Prodi, the Left Wing candidate at the function of Italian Prime Minister in 2006, in order to bring proofs of his competence, mentions the most important charges he covered (President of the Council of Ministers, President of the European Commission), while at the same time he explicitly states he is not in search of more professional satisfactions as he already had so many in his life, his only desire now being to make better reforms for the new generations.

3. Self presentation and contrast

According to general gestalt laws of cognition (Koffka 1935), people can better understand a belief if it is contrasted to another opposite belief. Therefore a quite effective strategy of self-presentation is to contrast yourself with the opponent and show how, while you have goodwill and proved to be efficient in several situations, the opponent has proved the contrary.

When one makes use of oppositions to emphasize the differences between oneself and the opponent, we say he is employing a distancing strategy. Distancing oneself from the other is a recurrent tactic in political discourse, where the goal is to prove that the arguer indisputably represents the better alternative among the two, while the opponent, which stands at the opposite pole, is precisely the opposite of the right alternative.

Scholars such as Dascal (2008) focused on the tendency arguers have to construct oppositions in a radical manner, with the aim of distancing themselves from the opponent. As Dascal points out, during debates, by their nature agonistic, oppositions are often polarized and led to extremes, resulting into dichotomies.

4. Radicalizing oppositions : from mere oppositions towards dichotomies[i]

Logically speaking a dichotomy is an “operation whereby a concept, A, is divided into two others, B and C, which exclude each other, while completely covering the domain of the original concept” (Dascal 2008, p. 28). But not every opposition usually regarded as a dichotomy fulfils in fact the necessary condition for being considered as such, i.e. logical exclusion of one term by the other. As pointed out by Dascal, while there are very few pairs of elements that are undisputedly dichotomous, the tendency of presenting simply opposing elements as dichotomous, i.e. as one insurmountably excluding the other, is high, possibly again due to the gestalt laws above. According to the personal interests and aims of the participants within the debate, the arguer may choose to employ dichotomous pairs of adjectives characterizing the self and the opponent in order to distance himself from the other.

According to Dascal, in fact, we can speak of a dichotomization tactic when the arguer is ‘radicalizing a polarity by emphasizing the incompatibility of the poles and the inexistence of intermediate alternatives, by stressing in the same time the obvious character of the dichotomy as well as of the pole that ought to be preferred’. (Dascal 2008, p. 34).

If this is the case, dichotomization, as Dascal points out, may lead to a polarization of the debate, where the two parties are presented as representing two views impossible to reconcile and as having opposing characteristics.

5. The concept of Strategic Maneuvering in argumentation

The aim of this paper is to analyze the tactic of dichotomizing oppositions as a strategic maneuver in terms of the extended pragma-dialectical theory of argumentation.

According to van Eemeren (2010), when engaging in an argumentative discussion, arguers have two contrastive goals: the dialectical goal which consists in maintaining reasonableness, and the rhetorical goal which refers to reaching effectiveness. Normally, the rhetorical goal is the one which tends to take the upper hand, jeopardizing a rational development of the discussion. Therefore, as van Eemeren puts it, people always have to maneuver strategically between the maintenance of reasonableness (if only for the sake of appearing reasonable in front of the others) and pursuing of effectiveness, i.e. having the best from the discussion. It is precisely for this reason of being divided between these two aims to reach that they have to maneuver strategically and don’t allow the desire of winning at any cost to take the upper hand.

The strategic maneuvering in argumentative discourse refers therefore to ‘the efforts that are made in the discourse to move about between effectiveness and reasonableness in such a way that the balance – the equilibrium – between the two is maintained’. (van Eemeren 2010, p. 41). If instead the rhetorical aim of reaching effectiveness prevails over the dialectical one, according to van Eemeren (2010), the maneuvering derails and the move results in a fallacy.

In maneuvering between the rhetorical and the dialectical goal, both arguers make some strategic choices according to the situation at hand and according to the stage of the discussion. Van Eemeren & Grootendorst (1992) and van Eemeren et al. (2002) distinguish four different stages of a critical discussion, namely: the confrontation stage where it becomes clear that there is a difference of opinion to be solved through critical discussion; the opening stage where the two participants in the discussion establish who is the Protagonist (the defendant of a certain thesis or standpoint) and the Antagonist (the attacker) and establish their material and procedural starting points; the argumentation stage where the Protagonist attempts to defend his thesis while the Antagonist tries to test the tenability of the Protagonist’s standpoint by subjecting it to the strongest criticism possible; and finally, the concluding stage where the result of the discussion is assessed.

In the argumentation stage, which is the stage on which I will focus within this paper, strategic maneuvering refers to choosing, from the topical potential at hand, the arguments which best adapt to the audience, while making a choice as to how the argumentative moves are to be presented in the strategically best way. These are according to van Eemeren (2010) the three aspects which coexist in a strategic maneuvring : topical selection, i.e. what arguments we choose in order to defend our standpoint; audience adaptation, i.e. knowing to whom these arguments will be presented in order to adapt them according to the audience’s preferences, and finally, the presentational devices, i.e. how these arguments are to be rendered in front of the audience.

As pointed out by van Eemeren, these three aspects are always intertwined: one cannot manifest itself in absence of the others. When planning an argumentation, the arguer has to choose what to say and how to say it in the strategically best way, while taking into account the listeners in front of him.

6. A case of strategic maneuvering with ethos

In this section I apply the notions of dichotomy and strategic maneuvering to an example of appeal to ethos during a political interview. The politician interviewed is Ségolène Royal, the Left Wing candidate (Socialist Party) at the French presidential elections in 2007 and Nicolas Sarkozy’s counter candidate. The interview I focus on was held on the 25th of April 2007 in the studios of the French TV channel France 2, three days after the first electoral tour, when Royal came out second with 25,87% votes against the candidate of the UMP (Union pour un Mouvement Populaire), Nicolas Sarkozy, who obtained 31,18% of the votes.

Before engaging in the analysis of the strategic maneuvering, I first provide the original fragments and the translations of Royal’s discourse, fragments which I used in the reconstruction of Royal’s standpoint and argumentation.

(1) “Et d’ailleurs, si je l’ai mis dans mon pacte présidentiel c’est parce que je sais que ça marche, que certaines régions l’ont déjà fait et je suis une femme pratique. Je suis moi-même une présidente de région, je ne parle pas dans le vague, dans le vide. Je suis l’élue d’un territoire rurale, on l’a vu tout à l’heure dans le portrait, depuis 15 ans. Je suis aujourd’hui confrontée en tant que présidente de région aux souffrances, aux difficultés, aux délocalisations, au chômage, à la précarité et je trouve et je cherche des solutions. Donc j’ai pris ce que marchait pour le mettre dans le pacte présidentiel. ” […]

“Voilà, je n’ai aucune revanche à prendre, je n’ai aucune revendication, je n’ai pas d’enjeu personnel dans cette affaire, je ne suis liée à aucune puissance d’argent, je n’ai personne à placer, je ne suis prisonnière d’aucun dogme, et au même temps je sens que les Français ont envie d’un changement extrêmement profond. Et mon projet c’est eux, ce n’est pas moi, mon projet. Mon projet ce sont les Français et aujourd’hui le changement que j’incarne. Le changement, le vrai changement c’est moi. Donc là il y a aujourd’hui un choix très clair entre soit continuer la politique qui vient de montrer son inefficacité, certaines choses ont été réussies, tout n’est pas caricaturé, par exemple le pouvoir sortant a réussi la lutte contre la sécurité routière, par exemple, mais beaucoup de choses ont été dégradées, Arlette Chabot, dans le pays, beaucoup de choses… ” […]

And if I put it in my presidential programme, it is because I know that this works, certain regions already made it and I am a practical woman. I am myself a Head of region, I don’t talk without having solid grounds. Since 15 years I have been representing a rural territory, I’ve been elected by its members, as we’ve just seen in the reportage. I am confronted as a Head of region with the pain, difficulties, displacements, unemployment, precariousness and I find and I look for solutions. So I took what was working in my region and I put it in my presidential program. […]

I have got no revenge to take, I have got no demand to make, I have got no personal benefice in this affair, I’m not bound to any financial power, I have got no one to place, I’m not prisoner of any dogma, and in the same time, I feel that the French people desire an extremely deep change. And my project is them, my project is not myself. My project is the French people and the change I embody today. The change, real change, is me. So today there is a very clear choice between either continuing the politics which has just shown its inefficacity, some things were well done, not everything is caricaturized, for instance the former party came out successful of the fight for security while driving, for instance, but a lot of things have been degraded in the country, Arlette Chabot, a lot of things. […]

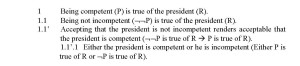

As mentioned by van Eemeren et al. (2002), in analyzing argumentation we first have to identify the standpoints at issue. Even if not explicitly stated, taken into consideration the context in which the discussion takes place, we can assume that Royal’s main standpoint is ‘I am the best alternative as a president’.

In analysing the strategic choices of the candidate under analysis, we will focus on the three intertwined aspects of the strategic maneuvering.

In the argumentation stage of the discussion, where she has to advance arguments in favour of her standpoint, she addresses the three aspects of the strategic maneuvering by choosing her arguments from the topical potential at her disposal. More precisely, from all the possible available arguments, she decides to emphasize the competence and benevolence side of her ethos, adapting this way to the audience’s assumed desire of having a competent and benevolent president. As far as the presentational means are concerned, she chooses an antithetical exposition of her own’s and of her opponent’s qualities, where emphasis is put on the difference between them.

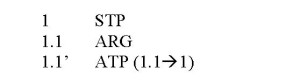

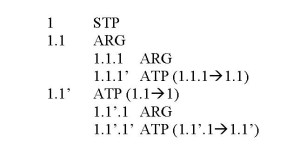

Following the pragma-dialectical model of reconstruction of the argumentation, I reconstructed Royal’s argumentation as a coordinative argumentation, supported by two main arguments advanced in defence of her main standpoint ‘I am the best alternative’. The two main arguments, none of them explicitly stated, are I am benevolent and I am competent.

I interpreted them as constituting a coordinative argumentation and not for instance a multiple one, as, in my opinion, both arguments are needed in order to support the standpoint ‘I am the best alternative’. According to van Eemeren et al. (2002), a multiple argumentation “consists of more than one alternative defense of the same standpoint” (van Eemeren et al. 2002, p. 63). Therefore, in case one of the arguments is rejected by the Antagonist, the standpoint may still stand because it is still defended by the remaining argument. This is not the case with coordinative argumentation, where “several arguments taken together constitute the defense of the standpoint” (van Eemeren et al. 2002, p. 63), and where one argument only is not capable of assuring a conclusive defense of the standpoint. In order to gain the audience’s trust and persuade them that she is the best alternative, Royal has to make them believe that she is both competent and benevolent, these being, according to Poggi (2005) and Falcone & Castelfranchi (2008), the two necessary components for trust. In fact, the Persuadee only decides to entrust his goals to the Persuader if he believes that the latter is both competent and benevolent, therefore both arguments employed are needed in order to conclusively support the standpoint.

These two main arguments are, in turn, supported by a range of sub-arguments. The first main argument, I am benevolent, is supported by the following sub-arguments:

(2) “I have got no revenge to take”;

(3) “I have got no demand to make;

(4) “I have got no personal benefit from this affair”;

(5) “I am not bound to any financial power” (i.e. I am not supported by any financial power which when I will be elected will expect a favour in return);

(6) “My project is the French people”;

(7) “My project is not myself”;

(8) “I do not have an ultimate step to reach”.

The second main argument, I am competent is again not explicitly expressed, even if all the sub-arguments she advances support it. Actually, to explicitly say that she is competent, might even backfire because it could be interpreted as showing off, or worse, as if there were a need for her to specify it, because people do not actually believe it is so. In fact, as mentioned also by van Eemeren et al. (2002), leaving premises or standpoints unexpressed is quite a common thing in argumentative discourse. The addressees of the discourse can nonetheless understand the unexpressed items with the aid of the Communication Principle (Grice 1975) and communication rules.

The ‘competence’ argument is supported by two sub-arguments: I am a practical woman and I am experienced. On the experience side, she decides to support her being experienced by sub-arguments such as:

(9) “I am myself a Head of Region”,

(10) “Since 15 years I have been representing a rural territory”,

(11) “I have slowly built my carrier step by step”.

As far as the practical side is concerned, she appeals to the following sub-arguments:

(12) “I find solutions”;

(13) “In my presidential program I only put things which work and which were previously tested”;

(14) “I do not speak without having sound grounds for what I say”.

6.1. Topical choice and audience adaptation in Royal’s argumentation

Every argument advanced to support the standpoint ‘I am the best alternative’ has a perfectly corresponding argument which emphasizes the opposite trait in the opponent. As she puts it, while she is benevolent and runs for the candidacy of France for the sake of the French people, Sarkozy is doing so for his own interest; while her competence has been proven during the years she was Head of the Poitou-Charentes Region, during the government of the Right Wing politicians (and therefore indirectly of Sarkozy, as the representative of the Right Wing), ”a lot of things have been degraded in the country”.

In order to prove Sarkozy’s self-interest, Royal resorts to arguments available from electoral events. In fact, while mentioning that she is not after revenge (“I have no revenge to take”), she is alluding at the Clearstream issue[ii], indirectly implying that the reason why Sarkozy is running for the presidency is because he wants to acquire power to get even with his enemy, namely Dominique Villepin.

A second argument defending the thesis that Sarkozy has a personal interest – again extracted from the topical potential at hand – concerns the fact that he is doing it for his ego. We learn from Royal that Sarkozy has previously asserted having ‘a last step to reach’ (“I do not have a last step to reach for myself, as he says”), and this last step consists exactly in becoming the president of France. She exploits his affirmation and turns it against him, by explicitly stating that, contrary to him, she does not have a last step to reach, emphasizing therefore her disinterest in becoming a president for herself.

I argue that she not only decided to exploit in her favour these events which put Sarkozy in a bad light, but that her choice from the topical potential was mainly influenced by them. Considering the situation at hand, Royal took the opportunity of emphasizing the benevolence side of her ethos, again on the basis of an opposition, by alluding to the Clearstream trial and by mentioning Sarkozy’s “last step to reach”, being certain that the audience would grasp what she implies, namely, that Sarkozy has a personal interest in becoming president. As often happens in adversarial debates, the topical selection of one of the arguers is influenced by the previous arguer’s sayings or doings. In this case, Royal picked up from the topical potential at her disposal those events which best supported her standpoint ‘I am the best alternative’ and which best adapted to the audience’s preference of having a president who puts the peoples’ interests before his own.

As already mentioned, arguing that the Persuader is benevolent is not enough to persuade the public to vote for him. He must also convince of his competence. These two aspects cannot hold without one another. As you would not entrust your goals to a benevolent but incompetent Persuader, you would not be persuaded by a competent, cunning Persuader but one for whom you are only a tool in achieving his own goals. Therefore both aspects need to be emphasized in order to gain the Persuadee’s trust.

Royal in her argumentation focuses on the competence side as well, advancing arguments such as I am a practical woman and I am experienced, arguments aimed at supporting the sub-standpoint I am competent. This sub-standpoint has as well a negative counterpart aiming at discrediting the results obtained by the Right Wing and therefore by Sarkozy, as the representative of the Right Party. While mentioning the politics which has “shown its inefficacy” and the big amount of things which “have been degraded in the country”, she refers of course to Right Wing politics. After mentioning the negative results of the opponent’s party, she does not refrain from admitting that “some things were well done, not everything is caricaturized, for instance the former party came out successful in the fight for security while driving”. In this way she emphasizes again her image of a fair candidate who acknowledges the other party’s successes and does not aim at denigrating him at any rate.

6.2. The dichotomizing strategy as a presentational device

So far we have seen Royal’s choices as far as the topical selection is concerned, more precisely the fact that she chooses her arguments from the events which shed a negative light on Sarkozy during his electoral campaign. We have also seen how she adapts to the audience’s preference of having a disinterested and competent president. As far as the third aspect of the strategic maneuvering is concerned, Royal makes extensive use of dichotomies: her personal and moral traits are always contrasted with those of Sarkozy. As we have already seen, Royal’s argumentation is antithetically construed: for every positive trait she adopts for herself, there is a negative counterpart which applies to her opponent:

I am competent versus the Right Wing (and Sarkozy as major representative) is incompetent;

I don’t have a personal interest versus Sarkozy is doing it for revenge and for “reaching the final step”.

Her use of polarizing terms can be seen in terms of a dichotomization strategy where the arguer wants to distance herself from the opponent as much as possible.

Her strategy is aimed at emphasizing her image as the best candidate for president, while in the meantime distance herself from the opponent, who is portrayed as the worst option.

Royal defines her position as incompatible with and antithetic to that of the opponent and tries to exploit the dichotomous position in her favour and against the opponent.

It is important to notice the way the dichotomies are stylistically presented. Royal chooses to present the dichotomies tacitly, without any direct reference to her rival and often with merely denying charges (I have got no revenge to take, I have got no demand to make, I have got no personal benefice in this affair, I am not bound to any financial power) letting the public infer that while Royal has no revenge to take, no demand to make, no personal benefits in this affair, there is someone who does have a revenge to take, a demand to make, or a personal benefit: namely Sarkozy. If none of the candidates had no personal interest in running for the presidency, there would be no need to emphasize the lack of interest in her case. Therefore, if Royal felt the need to emphasize this, we are dealing with important information for the public, (cf. the Gricean Quantity Maxim). Due to the political backgound, there is no need for Royal to explicitly state who exactly is the person she refers to, the public is perfectly capable of drawing the correct inference.

Similarly to the example analyzed by Dascal, in fragment (1) as well, Royal presents her opponent as not being a contender worthy of the audience’s trust. The dichotomy is therefore presented as unbalanced rather than a problem to be solved: it’s already pre-decided in favour of the arguing party.

6.3. Linguistic versus non linguistic presentational devices

Communication and therefore persuasion, as a subfield of communication, are multimodal. Gestures, gaze and facial expression contribute to the persuasion process.

We have seen how Royals employs a dichotomizing strategy in order to distance herself from Sarkozy with the aim of persuading the audience that of the two candidates, she is the best alternative.

We analyzed Royal’s appeal to ethos from the strategic maneuvering perspective and interpreted the dichotomizing strategy as one of the three aspects of the strategic maneuvering, namely the presentational devices.

I argue that linguistic presentational devices can be reinforced by non verbal strategies.

During the same presidential interview Royal employs hand gestures in a way that is revealing of her aim of distancing herself from her opponent. I interpreted these gestures as non linguistic presentational devices employed in order to reinforce the distance between herself and her opponent, a distance, as we have seen, already highlighted by a dichotomous characterization of the moral traits of the two parties. By making use of gestures as presentational devices, Royal helps the audience to clearly distinguish and differentiate between one candidate and the other. In most of the cases where she mentions the Right Wing and Sarkozy, she gestures with the right hand, while when mentioning her own party (Left Wing), she employs the left hand. Interestingly enough, the right hand is used also when negative concepts associated to the Right Wing are mentioned, such as: people who became rich because of real estate speculation, rich people who prefer not to work because they support themselves thanks to private incomes, and rich people in general, as opposed to the poor who are signalled instead by the left hand. Left hand gestures are also used when speaking about the working class and about work in general.

In Royal’s use, the right hand is therefore associated to the Right Wing and to the rich people and in general to negative concepts such as speculation, while the left hand generally stands for her own party and positive concepts such as work.

Royal encourages the audience to draw these correlations by helping them to reach the desired inference through the use of hands. Gestures in this case are not only a presentational device which reinforces the distance between the two candidates, by assuring the two participants a well delimitated and fixed spot in the audience’s mind, but fulfil a substitutive function as well. What is not explicitly stated (i.e. that voting for the Right Wing candidate equals to favouring the rich people who get richer and richer from real estate speculation and not by honest work) is nonetheless expressed by means of gestures.

Here are a few examples(3) from the interview in which Royal uses gestures to draw a line between the two parties and the values they defend. (an asterisk followed by R or L follows the word corresponding to a gesture of the Right (R) or Left (L) hand.

(15) Je ne veux plus de cette injustice-là. Il y a trop de riches (*R) d’un côté et trop de pauvres (*L) de l’autre.

I don’t want this injustice anymore. There are too many rich (*R) people on one side and too many poor people (*L) on the other side.

(16) Alors que quand j’entends le candidat de la droite (*R) dire qu’il va faire un bouclier fiscal…mais où va aller cet argent ? dans l’immobilier (*R), dans la spéculation (*R).

When I hear the candidate of the Right (*R) saying that he is going to make a tax measure to limit tax paid by taxpayers… But where is that money going? In the real estate (*R), in the speculation (*R).

(17) Faire revenir qui ? De toute façon tous ce qui veulent partir (*R), tous ces riches[iv](*R) […] La promesse du bouclier fiscal n’as pas empêché certain d’entre eux à partir (*R), alors qu’il promet le bouclier fiscal. Mais où va cet argent ? (*R) Il va dans la spéculation immobilière, c’est-à-dire que les catégories moyennes (*L) ont de plus en plus mal (*L) à se loger, parce qu’il y a de la spéculation (*R). Des gens très riches (*R) qui sont de plus en plus riches, avec le pouvoir actuellement en place (*R) […] Et c’est ça qui détruit l’économie (*R). Parce que à partir du moment où la rente (*R) est avantagée par rapport au travail (*R comes towards L), comme c’est le cas aujourd’hui (*R comes to the center) et comme c’est le cas dans le programme du candidat de la droite (*R returns to initial position to the Right), à ce moment-là, c’est l’économie qui est sapée (*R). Parce que si la rente est d’avantage récompensée que le travail, comment voulez-vous motiver les gens pour travailler, comment voulez-vous motiver les petites entreprises, si elles gagnent plus d’argent (*R) par la spéculation immobilière, qu’on créant des activités industrielles (*R comes towards L) dont la France a besoin?

Who to come back ? Anyway, all those who wanted to leave (*R), all those rich people (*R) […] The promise of a tax measure to limit taxes didn’t stop some of them to leave (*R) when he promised them the tax measure. But where is that money going? (*R) It’s going into the real estate speculation, that is, the middle class has difficulties to buy a house, because there is speculation (*R). Rich people (*R) who become even richer, because of the party on power at the present time (*R) […] And that’s what destroys economy (*R). Because if having a private income is more rewarding than working (*R comes towards L), which is the case today (*R comes towards center), and which is the case in the programme of the candidate of the Right, (*R goes back to intial position, to R), then economy is ruined (*R) Because if the private income is more rewarding than work, how do you want to motivate people to work, how do you want to motivate the small enterprises, if they earn more money by real estate speculation, then by creating the industrial activities (*R comes to the L) which France needs[v]?

A similar use of hands has been observed already by Calbris (2003) concerning Lionel Jospin’s gestures: “The Left in politics is situated at the locutor’s left. Jospin refers to the Left by systematically exploiting his left hand. Every allusion to the left government, such as the Left’s objectives, the Left’s political programme, are represented by the left hand. […] In a general way, the Leftist government is mentally situated on the left.” (Calbris 2003, p. 67, my translation).

We can say that in both cases but especially in Royal’s case, gestures have an active role in reinforcing the polarized positions of the two candidates, supporting therefore the dichotomy and emphasizing the distance between them, distance which cannot be bridged in any possible way.

7. Conclusion

In this paper I presented a case of appeal to ethos as a strategic maneuvering in political discourse. I showed how the candidate under analysis chooses her arguments while taking into account the intertwined aspects of the strategic maneuvering: topical potential, audience adaptation and presentational devices. As far as the third aspect is concerned, I showed how Royal’s arguments are subservient to a dichotomizing strategy. I argued that the linguistic dichotomization strategy is reinforced by a non verbal presentational device having the same goal of delimiting and distancing the two parties. Moreover, I showed how gestures not only reinforce the verbal component, but also have a substitutive role, helping the audience to infer what has not been explicitly stated in the verbal discourse.

My tentative hypothesis is that one of the reasons why Ségolène Royal lost the elections is precisely because of this permanent reference to the other party. Either through verbal or through non verbal means she always used to mention her opponent or his party. Besides the fact that mentioning the negative qualities of the opponent while not present could be interpreted by the audience as speaking bad of the other behind his back and therefore perceived as an unfair tactic, permanently mentioning Sarkozy – whether positively or negatively – allows him to be somehow permanently ‘present’ in the audience’s minds, even if not in the studio at the time being. Because as Lakoff puts it, the very mention of a thing or character irresistibly activates a frame in which that thing or character is dominant, and therefore makes it salient and powerful in the Receiver’s mind.

NOTES

[i] I am indebted to Bart Garssen for the suggestion about dichotomization tactics.

[ii] The Clearstream issue refers to an accusation of having obtained illegal kickbacks from arms sales, accusation directed at Nicolas Sarkozy by Dominique Villepin, the previous French First Minister. The list brought to Villepin’s attention, containing 89 French politicians, businesspeople and public figures involved in the illegal kickback money from arms sales and containing Sarkozy’s name as well, later proved to be a fake. Sarkozy accused Villepin of having used the forged list in order to derail his presidential bid and of having continued to use it even when he knew that it was fraudulent. Villepin denies any such accusations and says Sarkozy is using his influence in order to pursue a personal vendetta.

[iii] The examples were already mentioned in a previous paper (Poggi & Vincze 2009)

[iv] For this paper’s purpose a standard transcription is not necessary, therefore I developed a transcription method in order to signal the precise moments when right (*R) or left hand (*L) are employed by the speaker.

[v] All the translations from French into English were made by the author.

REFERENCES

Aristotle (2008). Retorica. Mondadori Printing.

Calbris, G. (2003). L’expression gestuelle d’un homme politique. Paris : CNR Editions.

Dascal, M. (2008). Dichotomies and types of debate. In F. H. van Eemeren & B. J. Garssen (Eds.). Controversy and Confrontation: relating controversy analysis with argumentation theory (pp. 27-51), Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Eemeren, F. H. van, & Grootendorst, R. (1992). Argumentation, communication and fallacies. A Pragma-dialectical perspective. New Jersey: Hillsdale.

Eemeren, F. H., van, Grootendorst, R. & Snoeck Henkemans, A., F. (2002). Argumentation. Analysis, Evaluation, Presentation. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers Mahwah.

Eemeren, F. H. van. (2010). Strategic maneuvering in argumentative discourse. Extending the pragma-dialectical theory of argumentation. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Falcone, R. & Castelfranchi, C. (2008). Fiducia e sfiducia. In I. Poggi (Ed.), La Mente del Cuore. Le emozioni nel lavoro, nella scuola, nella vita (pp. 89-112, Ch. 3), Roma: Armando Editore.

Grice, P. (1975). Logic and conversation. Syntax and Semantics 3, 41-58.

Koffka, K. (1970). Principi di psicologia della forma, Torino: Bollati Boringhieri.

Lakoff, G. (2006). Non pensare all’elefante! Modena: Fusi orari.

Poggi, I. (2005). The goals of persuasion. Pragmatics and Cognition 13, 297-336.

Poggi, I. & Vincze, L. (2008). Showing disinterest. A persuasive strategy to win the electors’ trust. Proceedings of the Workhop on Computational Models of Natural Arguments 49-54, CMNA, Patras, Greece.

Poggi, I. & Vincze, L. (2009). Gesture, gaze and persuasive strategies in political discourse. In M. Kipp (Ed.) Multimodal corpora. From models of natural interaction to systems and applications (pp. 73-92), Berlin: Springer Lecture Notes in Computer Science.