Speaking Papiamentu ~ On Re-Connecting To My Native Tongue

03-07-2024 ~ It starts at Schiphol, the Amsterdam airport. Before that, I am still immersed in my life in Jerusalem, busy with family matters and with grassroots activism against the Israeli occupation, while under pressure to finish grant proposals for the multicultural Jerusalem feminist center and art gallery where I work. I do not have time to connect emotionally to my trip, which still feels more like a yearly obligation to visit my elderly mother in Curaçao, when I would rather spend my precious vacation time trekking in Turkey or Nepal.

03-07-2024 ~ It starts at Schiphol, the Amsterdam airport. Before that, I am still immersed in my life in Jerusalem, busy with family matters and with grassroots activism against the Israeli occupation, while under pressure to finish grant proposals for the multicultural Jerusalem feminist center and art gallery where I work. I do not have time to connect emotionally to my trip, which still feels more like a yearly obligation to visit my elderly mother in Curaçao, when I would rather spend my precious vacation time trekking in Turkey or Nepal.

I usually have a few hours to kill, not enough to take the train into Amsterdam and visit old friends, which I do on my return trip when I have almost twelve hours between planes. And so, I silently wander around the airport, feeling a little like a spy, as I do in Jerusalem when I hear Dutch tourists speaking on the street, not suspecting that I, who probably look like a local to them, would understand. Not identifying myself as a speaker of Dutch, I take in the talk, smiling to myself, my little secret.

Here, in transit at the airport – a liminal space par excellence – I sometimes pretend to be a total stranger and address the salesperson in English. Perhaps that has more to do with the fact that I have not yet woken up my slumbering Dutch, or do not want to give away my unfamiliarity with the currency and other taken-for-granted facts of daily life in the Netherlands.

Or perhaps it is my resistance to being taken for an “allochtoon” – that polite way they refer to the “not really Dutch,” who nevertheless hold Dutch citizenship – a category that groups together the mostly Moslem migrants and those of us, from the former Dutch colonies, blacks and whites alike. It is a label that had not yet been coined when my schoolteachers in Curaçao taught us to see Holland as our “mother country,” to sing Wilhelmus Van Nassauwe, the Dutch national anthem, on Queen Juliana’s birthday and to accept the Batavians, a Germanic tribe, as “our” ancestors. They say that when you count, you invariably give away your mother tongue – to this day I count not in Papiamentu, but in Dutch, so totally did I embrace the colonial language.

I was four when I learned Dutch in kindergarten. I remember the feeling of utter embarrassment when everyone expected me to speak Dutch with my cousins whose father was Dutch, and I ran away crying. I was losing the secure ground that Papiamentu provided, having to jump into the deep waters of a foreign language without a life-vest before I knew how to swim.

Very soon, however, I was speaking Dutch fluently, determined to excel in the language. I wanted to know it even better than the Dutch children whose parents came from Holland. I spoke Dutch with all my school friends, even though most of us spoke Papiamentu at home, including the handful of schoolmates from my own community, the Sephardic Jews who settled on the island in the seventeenth century, after fleeing the inquisition in Portugal and Spain.

In my elementary school days, the teachers forbade us to speak Papiamentu even in the schoolyard, claiming it was the only way to learn proper Dutch. And so, I read, wrote, and thought in Dutch – it became my first literary language, as Papiamentu was basically only a spoken language at that time. Now, as I write this in 2007, after forty-two years away from the Dutch speaking world, my Dutch gets rusty, until I find myself again surrounded by its sounds and it returns to me and becomes almost natural.

I roam around the halls of the airport’s immense shopping center, not quite knowing what I am looking for. It is rather busy at the camera counter – I realize it is not a place to come with all my questions about which new camera to buy, my first digital SLR, after getting excited with the results of my digital point and shoot. Up to now, I had refrained from following the footsteps of all the other photographers in my family and never took my photography seriously. All that changed when I realized that editing my digital photos could finally give me the control over my images that I sought.

No, there is no point shopping here, I’d better look at cameras in Curaçao at a more relaxed pace, where the prices will certainly be lower. At least they used to be, when I was growing up and the island was still a duty-free paradise for American tourists.

Suddenly I remember that once, in these huge avenues of shops designed to entice travelers on the move, there used to be a stand with fresh, raw herring. I do not see it anymore, even though this is still the season of the celebrated first herring catch – the end of June. It fills me with longing, even though “new” herring was not something we ate at my home, it is what the “real Dutch” loved. Raw herring is a taste I developed later, and yet, it is so very much a taste from that past, perhaps from my acquired Dutch identity, and I feel that eating herring now would prepare me for my return.

I search for a shop that used to sell every possible variety of drop – salted licorice – yet not daring to ask for it, perhaps so as not to expose my weakness, my secret addiction or not admitting it to myself. I have a good spatial memory – I remember you had to walk through a drug store to get to it, and it is a long way from the main shopping center with the largest stores. I find the drugstore, but now there is a cosmetics counter in the back. The millions of foreigners who pass through this airport obviously do not have the taste for the salty and pungent licorice, a taste that you only acquire if you grow up in Dutch culture, and so it was not profitable to maintain a shop that specializes in salted licorice.

Without quite making a conscious decision, I meander into a store where they sell Dutch delicacies – cheeses, fish, chocolates, biscuits. And there, on one of its shelves, I see a large box of salted licorice, which I buy immediately. I taste one, and as soon as it has melted in my mouth, I take another, and yet another. It is not that salted licorice reminds me, like the Proustian petite madeleine, of a lost childhood, rather, it reawakens my desire for more and more salted licorice. I can forget about licorice completely, go about my daily life in Jerusalem without knowledge or reminiscence of it, without even longing for it, in fact, I do not care much for sweets, and then, suddenly, as soon as I taste it again, I turn into a licorice addict. It is a lot easier not to eat it at all, than to eat it in moderation.

I start to move towards the gate, still sneaking my fingers into the box of licorice that is now in my backpack, hidden from my own conscience, as I suppress the certain knowledge that soon I will develop a bellyache. There is a long line outside the closed hall where a second hand-luggage check is held before you can enter it – much like the flights to Israel – but it is not weaponry that is being sought here, but drugs.

Most of the people in the line are Afro-Antilleans, seemingly living in Holland and going back to the islands for a family visit, sometimes accompanied by a Dutch spouse and children in all shades of skin color, wearing their best clothes. There is also an assortment of casually dressed Dutch tourists, mostly young couples out to spend their vacation in the tropics, invariably scuba diving at the magnificent coral reefs – something that I, as a native, never learned to do.

I begin to hear Papiamentu, a word here and there, a mother calling a child, snippets of a conversation. Somehow, I still feel a little like a foreigner, an outsider, an eavesdropper. But the reality of the past week, the tense work on the proposals is all gone, as if it never existed. Even my exasperation with the Israeli occupation of Palestine has left me, as if a heavy burden has been lifted from my back. I am relieved not to have to think about it, for I am essentially an introspective person who realizes she must take a moral stand and become an activist, despite herself.

Slowly, my mouth full of licorice, I start to get that familiar sensation that I recognize from my previous border-crossings in Amsterdam. I cannot give it a name, it is a sense of strangeness, of looking at myself from the outside, this licorice-eating woman who is standing in line with other speakers of her mother tongue, when she lives in an everyday reality where nobody really knows her Papiamentu-speaking-self, where she has absolutely no occasion to let it out. I realize I am a stranger to those closest to me, and how this part of me, the woman-who-speaks-Papiamentu, is unknown to them, cannot be known to them.

There is a song by a popular Israeli singer who immigrated from Buenos Aires, that speaks of living his life in Hebrew and that he will have no other language – yet in the depths of the night, he still dreams in Spanish. I do not even dream in Papiamentu. This part of me is totally absent in my life in Israel, where I have nobody with whom to speak my language – as far as I know, I am the only Papiamentu speaking person in Jerusalem. And so, as soon as I return to Jerusalem, I stop living in Papiamentu. Nobody there knows that part of me.

When I asked a friend what it felt like to live in a country where French, her mother tongue, is not spoken, she answered that language is a home you can take with you to wherever you go. She has her French-speaking relatives and enjoys movies and books in French. For me, Papiamentu cannot possibly be a home away from home – without an expatriate community with which to connect, when my mother tongue has less than 300,000 speakers and none of them can be found in my immediate vicinity and when the phone connection to that distant country that nobody else here calls, has always been outrageously expensive.

I cannot even find solace in writing my mother tongue, living in a Papiamentu world of my own – since Papiamentu, at least for me, is not a written language. Its orthography was only formalized after I left the island, and I still find it strange to read, with its strict phonetic spelling, so that words originating from Spanish or Dutch are written in unfamiliar ways.

Feeling that Curaçao means nothing to those who have never lived there and who do not know my language, I do not dwell on my background – I do not talk about where I come from. I am not willing to play the role of an exotic bird from a little island in the Caribbean. On the other hand, I refuse to be thrown into better-known categories, such as “Argentinean”, sharing little with South Americans – other than their music and dance – as I learned Spanish only in sixth grade, and unlike English, it always remained a foreign language to me.

And so, rather than allowing myself to feel the loneliness, I let that part of me go – I have erased it. It is a part of me that I do not speak about, if I cannot speak from it. I do not even miss my Papiamentu-speaking-self when away from the island. I do not live with a sense of loss, longing for a vanished childhood, for a hidden identity, for my language as a home – just like, in my daily life, I can completely forget about the pleasures of eating salted licorice. Until recently, I did not realize that I have been paying a price for the erasure of such a central part of who I am. Rather than being a stranger to those around me, I was a stranger to myself.

It is, perhaps, because I am not an exile that I do not feel that sense of loss – I have had the privilege to return to Curaçao almost every year since I have been living in Jerusalem. Or rather, I do not believe I deserve to indulge in a feeling of loneliness, after all, I left my native country voluntarily to study abroad, knowing I would never return to live there. I am not like the homeless, the displaced, the refugees who were forced to abandon their language.

Perhaps I can speak of a sense of self-exile, as I did not find my place in the complex colonial society of the island, with its racial, class and gender segmentation and hierarchy, its strict internal borders, where everyone had their place, and knew it. I did not want to accept the place I was assigned, as a female member of a privileged class, whose movements across these internal borders, unlike those of the men of that class, were heavily restricted.

At a young age, I became aware that each social group took for granted its own conception of the world, its own truth, which often was in contradiction to the others, and that kept them within their borders. And so, even when living on the island as a high school student, I had already learned to be an outsider – one who refused to see herself as embedded within the internal boundaries and tried to see beyond them.

I was like the stranger, a concept developed by the sociologist Georg Simmel referring to someone who is both near and far, who is spatially inside a social group, yet at the same time, not quite a member of it – not committed to its norms, values, definitions of reality. It means being in liminal space between the groups, a position that frees you to take on a broader perspective, allowing you to be more “objective” (1). In other words, I was already a budding anthropologist, thriving on the threshold – the limen – between different ways of life.

It is this adaptability as an outsider that prepared me to cross cultural and language borders without experiencing culture shock – to adopt English with utmost ease, even before I went to college in the USA in the second half of the stormy sixties, where I found myself again in the liminal spaces of critical thought and the struggle for social justice, together with other foreigners and with students of color – a period that has consolidated my social consciousness.

A year or so after graduating, I had no difficulty adapting to life in Jerusalem, becoming fluent in spoken Hebrew when I moved here with the Jewish American man I met at the university in the Boston area and married, raising two children who have always insisted on speaking Hebrew with us.

My life in Jerusalem revolves around spoken Hebrew, while I also nourish my English, which has gradually replaced Dutch as my literary language. In fact, it is the only language in which I am able to write today. I never became proficient in written Hebrew and do not feel pressured to perfect it, another expression of my political ambivalence about living in Israel. I guess I take pleasure in being a perennial outsider.

I do not even have Israeli nationality, as the Dutch at the time did not permit dual citizenship, and that suits me well to this day. In 1970, when we first arrived in Jerusalem, I saw it as a bit of an adventure trip to a young, exciting country with an ethnically diverse, anthropologically intriguing society. The occupation of the Palestinians did not appear as malevolent as it became over the years. I am certain I would not have wanted to settle here today.

As I stand in line at the Amsterdam airport, catching a plane to Curaçao, I hear my mother tongue and smile at the people waiting to get on the plane, in acknowledgment that I understand. There is no sense of spying anymore; it is replaced by an eagerness to identify myself as a speaker of Papiamentu. I blend in with those waiting to be checked, voicing my agreement, of course, in Papiamentu, that the waiting is taking much too long.

Finally, on the plane, at my window seat, for which I always ask so I can see, and photograph, the island when we are landing, I realize I am shedding the layer of my everyday life in Jerusalem, like an overall, or rather a heavy spacesuit that cloaks my entire body and dictates my movement. It takes me a while to recognize that Papiamentu-speaking-self that is crammed inside, the way I think, twinkle my eyes, dance the tumba in Papiamentu. I regain a visceral quality, not just a language – all those things that get lost in translation.

An American friend, on hearing me switch to Papiamentu while on the phone with one of my cousins living in Boston, exclaimed in delight: “you become a totally different person when you speak Papiamentu!” It was a moment of deep recognition, of acknowledgement. She was the first person who was not from the island, who saw me, and her remark, like a paradigm leap, enabled me to see myself, and feel the person that I am, fully, with all my layers of language.

The flight is long, sometimes close to ten hours, or even more if there is a stopover in St. Maarten or Bonaire, two other Dutch islands in the Caribbean. I try to sleep and seldom watch the movie, while I make a concerted effort to wean myself, temporarily, from my licorice habit. I speak Dutch and Papiamentu on the plane with the flight attendants or the people sitting next to me.

If I flew a different airline or route, say via Madrid and Caracas, the transition to my Papiamentu-speaking-self would be delayed. Perhaps it would be more abrupt. Would I then have time to reflect on this sense of strangeness that overcomes me at the Amsterdam airport? Perhaps, I would immediately adopt my Papiamentu-speaking bearing from the moment I land, as if I had never been away. I would not have the chance to see myself from the side, as a woman I do not know in my ordinary life. I would not feel the pain and loneliness of not being able to share such a vivid part of myself. I would not have come to writing this essay and realizing that this part of me is a stranger in my other life.

Who is this woman who becomes again a speaker of Papiamentu, when standing in line at the Amsterdam airport? There, I reconnect with an inner core that I have denied myself all those years. There is the music of the language – juicy words like barbulète, kokolishi, warawara, maribomba – just their sounds make me dance, take me back to a childhood rich in fantasy and folktales.

Yes, there is a sense of coming home when I speak Papiamentu – a mother tongue is, after all, a home, but not one I can take with me to places where there are no other speakers. It is a home in the sense that it makes me whole again, that fills me with the lifeforce of who I fully am.

From the airplane, I finally catch a glimpse of the island below. My heart begins to somersault, as more and more of my island becomes visible. Enthralled I begin to photograph. I have always loved to look down from airplanes, to see landscapes as gigantic, two-dimensional paintings. But most of all I love to look at Curaçao – seeing it not abstractly, but in its very physical manifestation – its large inner bays, shaped like fig-leaves with a narrow passage to the sea; the waves splashing against the rocks of its rugged north coast, and its flat plain of dry, red sands along the sea near the airport. I already feel myself there as I identify all the bays where I have been, or the hills I have climbed with my brother Fred. From the air, I get ideas for new places to explore, and of course, to photograph.

And now, a few years later, I realize that something is starting to happen to me when I photograph the island on my yearly visits to my mother. It is through my photography that I begin to look more closely at the island, becoming more and more connected. I discover that I can transcend the outsider stance that seems to be inherent in the act of taking pictures, meeting my subject on a deeper level without holding back, as I am thrown into the realms of the senses, the psyche, of history and memory.

And the more I open myself to the island’s rhythms, sounds and textures through my lens, the harder it becomes to leave my language behind. To let the woman that I am on the island be erased.

Back in Jerusalem, I continue to work with the photos – enhancing the digital images and uploading them to my photo-website, while also creating photobooks. In other words, I am no longer cutting myself off from the island.

Sharing the images, I see that people really look, and I begin to realize that through my photographs, they can see a part of myself that I did not let them know before. I realize that with my photographs, I am speaking Papiamentu. That I am saying kokolishi, maribomba, warawara. And I am being understood.

Notes:

1. Georg Simmel, “The Stranger”, Kurt Wolff (Trans.) The Sociology of Georg Simmel. New York: Free Press, 1950, pp. 402 – 408.

Bio:

Rita Mendes-Flohr (née Mendes Chumaceiro) is an ardent trekker, an exhibiting art photographer, and the co-founder, former director, and curator of a feminist art gallery. An eternal outsider, she was born in Curaçao, studied in Boston and lives in Jerusalem, feeling at home only in the in-between. Coming to writing at a later stage in her life, she has published a socio-architectural memoir/novel of her multicultural Caribbean childhood, (in Hebrew translation) inspired by her background in architecture and anthropology and writes introspective travel essays (in English) that she plans to publish as a book together with her photographs of those journeys. Her work can be viewed on her site: www.ritamendesflohr.com

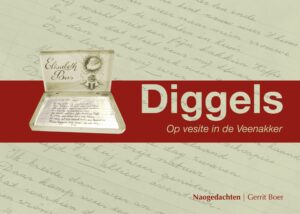

Gisteravond was ik al lezend een paar uur in de Altingerhof in Beilen. Op de afdeling voor dementerenden, de Veenakker, woonde de opoe van Gerrit Boer.

Gisteravond was ik al lezend een paar uur in de Altingerhof in Beilen. Op de afdeling voor dementerenden, de Veenakker, woonde de opoe van Gerrit Boer.