ISSA Proceedings 2006 ~ Putin’s Terrorism Discourse As Part of Democracy And Governance Debate In Russia

Abstract

Abstract

This paper [i] presents a study of President Putin’s use of the issue of terrorism in public debate in Russia. President Putin’s speech made in the wake of the Beslan tragedy, on September 4th, 2004, is examined. The logico-pragma-stylistic analysis employed in the paper describes communicative strategies of persuasion employed by the speaker and investigates how the Russian leader uses the issue of terrorism to further his political goals. The terrorism debate is analysed within a wider context of democracy and governance debate between the President and the liberal opposition.

Key words: argumentative discourse, rhetoric, pragmatics, pragma-dialectics, fallacies.

This paper is a study of the use of the issue of terrorism in public debate in Russia. It examines President Putin’s address to the nation in the wake of the Beslan terrorist attack, on 4 September 2004.

The study doesn’t pretend to be an exhaustive treatment of the topic; rather it aims to present a logico-pragma-stylistic analysis of the speech, to identify communicative strategies of persuasion employed by the speaker, and to investigate how the Russian leader used the problem of terrorism to further his political goals. The terrorism debate is analysed within a wider context of the democracy and governance debate between the President and a liberal opposition.

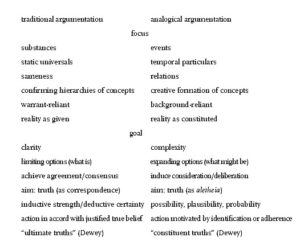

In trying to persuade his or her audience a skilled arguer assesses the audience and the issues at hand. When composing a message the speaker takes into account of several factors: the medium of communication (electronic mass media, print media), topic of discussion, audience (gender, level of education, expertise in the topic under discussion, rationality/emotionality, degree of involvement in the problem, level of life threat presented by the problem, etc), nature of the discussion (i.e. whether it is a direct dialogue with an opponent in a studio or an indirect dialogue through electronic or print media), applicable conventions (e.g. parliamentary procedures), and finally a broader, cultural and political context in which communication is taking place including such elements as openness/restrictiveness of the political regime, moral dilemmas and cultural taboos existing in the society, and traditions of conducting discussions inherent in the culture.

The process of assessment and adaptation of the issues to the audience establishes a communicative strategy of persuasion. The key decisions in a communicative strategy are to choose targets to appeal to and to prioritize them. While there are a wide variety of possible targets of appeal, it is possible to identify three major ones, people’s mind, emotions, and aesthetic feeling. An appeal to people’s reason or rational appeal is based on the strength of arguments. Emotional appeals arouse in the reader or listener various emotions ranging from a feeling of insecurity to fear, from a sense of injustice to pity, mercy, and compassion. Aesthetic appeals are based on people’s appreciation of linguistic and stylistic beauty of the message, its stylistic originality, rich language, sharp humour and wit.

Rational appeals can be effective in changing beliefs and motives of the audience because they directly influence human reason, which plays a role in beliefs and motives. Emotional appeals are persuasively effective because they exploit concerns, worries, and desires — the arguer “speaks to people’s hearts”. Aesthetic appeals are persuasively effective when they change people’s attitudes to the message and through the message to its author. By changing attitudes from those of disapproval or reservation to appreciation or even admiration, the author increases the recipient’s susceptibility to persuasion. People will be more willing to accept the arguer’s reasoning after they have experienced the communicator’s giftedness as the author of the message (Goloubev 1999). The three components of the logico-pragma-stylistic analysis roughly correspond to these three major appeals of the argumentative discourse: rational, emotional and aesthetic.

Let us now turn to Putin’s speech. The breakdown into paragraphs follows the version published on the official site of the President of the Russian Federation. The only amendments change the translation of some sentences to make the English follow more closely the original Russian, syntactically and semantically. The speech is divided into explicit parts; paragraphs are numbered to facilitate analysis.

4 September 2004

Moscow, Kremlin

Address by President Vladimir Putin

Part 1

1. Speaking is hard. And painful.

2. A terrible tragedy has taken place in our world. Over these last few days each and every one of us has suffered greatly and taken deeply to heart all that was happening in the Russian town of Beslan. There, we found ourselves confronting not just murderers, but people who turned their weapons against defenceless children.

3. I would like now, first of all, to address words of support and condolence to those people who have lost what we treasure most in this life – our children, our loved and dear ones.

4. I ask that we all remember those who lost their lives at the hands of terrorists over these last days.

Part 2

5. Russia has lived through many tragic events and terrible ordeals over the course of its history. Today, we live in a time that follows the collapse of a vast and great state. A state that, unfortunately, proved unable to survive in a rapidly changing world. But despite all the difficulties, we were able to preserve the core of that giant – the Soviet Union. And we named this new country the Russian Federation.

6. We all hoped for change. Change for the better. But many of the changes that took place in our lives found us unprepared. Why?

7. We are living at a time of an economy in transition, of a political system that does not yet correspond to the state and level of our society’s development.

8. We are living through a time when internal conflicts and interethnic divisions that were once firmly suppressed by the ruling ideology have now flared up.

9. We stopped paying the required attention to defence and security issues and we allowed corruption to undermine our judicial and law enforcement system.

10. Furthermore, our country, formerly protected by the most powerful defence system along the length of its external frontiers overnight found itself defenceless both from the east and the west.

11. It will take many years and billions of roubles to create new, modern and genuinely protected borders.

12. But even so, we could have been more effective if we had acted professionally and at the right moment.

13. In general, we need to admit that we did not fully understand the complexity and the dangers of the processes at work in our own country and in the world. In any case, we proved unable to react adequately. We showed ourselves to be weak. And the weak get beaten.

14. Some would like to tear from us a “fat chunk” of the territory. Others help them. They help, reasoning that Russia still remains one of the world’s major nuclear powers, and as such still represents a threat to them. And so they reason that this threat should be removed.

15. And terrorism, of course, is just an instrument to achieve these aims.

16. As I have said many times already, we have found ourselves confronting crises, revolts and terrorist acts on more than one occasion. But what has happened now, this crime committed by terrorists, is unprecedented in its inhumanness and cruelty. This is not a challenge to the President, parliament or government. It is a challenge to all of Russia. To our entire people. It is an attack on our country.

Part 3

17. The terrorists think they are stronger than us. They think they can frighten us with their cruelty, paralyse our will and sow disintegration in our society. It would seem that we have a choice – either to resist them or to agree to their demands. To give in, to let them destroy and have Russia disintegrate in the hope that they will finally leave us in peace.

18. As the President, the head of the Russian state, as someone who swore an oath to defend this country and its territorial integrity, and simply as a citizen of Russia, I am convinced that in reality we have no choice at all. Because to allow ourselves to be blackmailed and succumb to panic would be to immediately condemn millions of people to an endless series of bloody conflicts like those of Nagorny Karabakh, Trans-Dniester and other well-known tragedies. We should not turn away from this obvious fact.

19. What we are dealing with are not isolated acts intended to frighten us, not isolated terrorist attacks. What we are facing is direct intervention of international terror directed against Russia. A total, cruel and full-scale war that again and again is taking the lives of our fellow citizens.

20. World experience shows us that, unfortunately, such wars do not end quickly. In this situation we simply cannot and should not live in as carefree a manner as previously. We must create a much more effective security system and we must demand from our law enforcement agencies action that corresponds to the level and scale of the new threats that have emerged.

21. But most important is to mobilise the entire nation in the face of this common danger. Events in other countries have shown that terrorists meet the most effective resistance in places where they not only encounter the state’s power but also find themselves facing an organised and united civil society.

Part 4

22. Dear fellow citizens,

23. Those who sent these bandits to carry out this horrible crime made it their aim to set our peoples against each other, put fear into the hearts of Russian citizens and unleash bloody interethnic strife in the North Caucasus. In this connection I have the following words to say.

24. First. A series of measures aimed at strengthening our country’s unity will soon be prepared.

25. Second. I think it is necessary to create a new system of coordinating the forces and means responsible for exercising control over the situation in the North Caucasus. Third. We need to create an effective anti-crisis management system including entirely new approaches to the way the law enforcement agencies work.

26. I want to stress that all of these measures will be implemented in full accordance with our country’s Constitution.

Part 5

27. Dear friends,

28. We all are living through very difficult and painful days. I would like now to thank all those who showed endurance and responsibility as citizens.

29. We were and always will be stronger than them, stronger through our morals, our courage and our sense of solidarity.

30. I saw this again last night.

31. In Beslan, which is literally soaked with grief and pain, people were showing care and support for each other more than ever.

32. They were not afraid to risk their own lives in the name of the lives and peace of others.

33. Even in the most inhuman conditions they remained human beings.

34. It is impossible to accept the pain caused by such loss, but these trials have brought us even closer together and have forced us to re-evaluate a lot of things.

35. Today we must be together. Only so we will vanquish the enemy.

This message was delivered the next day after the end of the standoff between terrorists and Russian security forces during a school siege in Beslan, in Russia’s southern republic of Northern Ossetia. There were more than 1,200 people taken hostage during the three days of terror. Nearly 340 people died, 176 of them children. More than 500 were wounded. A message posted on a pro-Chechen website afterwards confirmed what many believed: that the architect of the violence was Shamil Basaev, the most notorious of the Chechen militants. Russia was in shock.

Obviously such an emotional subject demands an emotional response from the country’s President. Rightly, therefore, the speaker makes an emotional appeal a priority. The message is clearly meant to comfort and uplift, unify and instil confidence in the people. In Part 1 especially and throughout the text, we see expressions of sympathy and condolence. But who must these words comfort and uplift, in whom must they invoke hope and confidence? Who is the audience the speaker addresses his message to? These questions are not as straightforward as they seems. The primary audience is not the people of Beslan whom the terrorist attack immediately affected (although they are mentioned in the concluding part of the speech). The primary audience is all the people of Russia. Even the town of Beslan is referred to as a Russian town rather than a Northern Ossetian town (2), which would have distanced it from the country as a whole. The recipients of the message are referred to as fellow citizens (22), citizens of Russia (23), and friends (27) but never as Ossetians.

This is done to achieve two objectives. On the one hand, it serves to indicate that Russians are a united nation (inspiring confidence). On the other hand, it acts to reinforce the identification of the speaker, the President of the country, with his audience, his fellow countrymen (expression of empathy). Several linguistic devices are employed to produce the said effect. One of them is the repetition of key words or phrases: the noun Russia and adjective Russian are mentioned 9 times in the Russian original text, the personal pronoun we and the possessive pronoun our in different grammatical cases are used a record 33 times. The phrases we must be together,… only together (43) are other key words that are repeated.

An interesting case to examine is the use of the word people, which is found in the text both in the singular and the plural form. Used in the singular (a) people refers to the whole Russian nation: This is not a challenge to the President, parliament or government. It is a challenge to all of Russia, to our entire people (16). In the plural the word peoples refers to various ethnic groups composing the Russian Federation: Those who sent these bandits to carry out this horrible crime made it their aim to set our peoples against each other, put fear into the hearts of Russian citizens and unleash bloody interethnic strife in the North Caucasus (23). In this sentence, Putin takes great care to emphasise that different ethnic groups living in the Northern Caucuses are one nation. He does that by using an umbrella term citizens of Russia to refer to the people belonging to these ethnic groups. The speaker not only talks about a united Russia but emphasizes the country’s greatness: Russia is referred to as the core of a great state, the giant – the Soviet Union (5), as a country protected by the most powerful defence system along the length of its external frontiers (10), as one of the world’s major nuclear powers (14).

Having built up the idea of unity in Part 1 and Part 2, President Putin, at the end of Part 2, introduces one of his main theses: all of Russia is under attack (16). Later he reinforces his claim: What we are dealing with are not isolated acts intended to frighten us, not isolated terrorist attacks. What we are facing is direct intervention of international terror directed against Russia. A total, cruel and full-scale war that again and again is taking the lives of our fellow citizens (19).

The message contains an important juxtaposition: Russia versus her enemies. And that is the only juxtaposition. There is no division within Russia itself: the State and the People are one whole.

Let us examine the rhetorical images of the opposing parties. The speaker creates an image of the Russian people as caring, courageous, humane people and juxtaposes this image with the enemies’ image as not just murderers but murderers of defenceless children (2), terrorists (4, 16, 17, 21, and 27), international terror(ists) (19), and bandits (23). In fact, the speaker ends his message with the word enemy (35), which indicates the importance President Putin attaches to the concept. Describing the enemy the speaker avoids any mention of their demands to withdraw Russian troops from Chechnya. Interestingly, never once was the word Chechnya mentioned in the whole speech. This is done to remove any connection between Beslan and the ongoing conflict in the neighbouring republic. The speaker creates the impression that Northern Caucasus is currently a peaceful region and the bandits who committed the crime strive to spark a bloody feud between the peoples of the region similar to bloody conflicts in Nagorny Karabakh between Azerbaijan and Armenia, in the Trans-Dniestr Republic between this self-proclaimed, unrecognized state and Moldova it had been part of, and other well-known tragedies (18).

Putin’s emphasis is on the international character of the threat that plagues the modern world, hence the mention of the popular term the new threats (20), the reference to other countries in the next paragraph (21), as well the implication that the bandits who carried out the crime did not act on their own accord but were sent by those abroad who masterminded the terrorist attack (23). Even more striking is the reference to world conspiracy of presumably foreign policy-makers who condone terrorism against Russia. Some of them condone it because they see an opportunity to chip away a “fat chunk” of Russian territory, others see in Russia, one of world’s biggest nuclear powers, a threat to them, the threat that has to be removed (14).

As we have noticed before the message is of a highly rhetorical character. It abounds in stylistic devices which enhances its aesthetic appeal. Note the use of repetition of the word we throughout the text, parallelism of expression in Part 2: we live in a time … (5), we all hoped… (6), we are living … (7), we are living … (8), and we stopped… (9). As William Strunk Jr. points out in his book The Elements of Style a good writer should express coordinate ideas in similar form. “This principle, that of parallel construction requires that expressions similar in content and function be outwardly similar. The likeness of form enables the reader to recognize more readily the likeness of content and function” (Strunk and White 1979: 26). Many important statements are expressed in very short sentences, which helps attract the attention of the audience: And the weak get beaten (13); It is an attack on our country (16); Today we must be together. Only so we will vanquish the enemy (35). The speaker deliberately breaks his sentences into two, which again allows him to repeat certain key words, achieve sharpness of expression and increase the aesthetic and emotional effects of the message: Speaking is hard. And painful (1); We all hoped for change. Change for the better (6); This is not a challenge to the President, parliament or government. It is a challenge to all of Russia. To our entire people. It is an attack on our country (16). The latter sequence is also an example of the afore-mentioned stylistic device of parallelism. Another stylistic device employed to enhance the aesthetic appeal is the rhetorical question Why? (6) The question allows the arguer to make a pause and draw the listener’s attention to the points to follow.

Rational appeal appears to be the last target in President Putin’s communicative strategy. This assessment is based on the number of sentences containing argumentation, which is comparatively small. As we have already mentioned, the purpose of the message is not to convince but rather to empathize and explain. As far as specific proposals for a course of action are concerned the speaker makes only a few blueprint points, leaving proper arguments for concrete proposals for a later message.

Having said that, the message does contain a clear line of argument whose purpose is to justify the tough line President Putin is pursuing towards Chechnya and vindicate his actions during the crisis. We have touched upon the first issue already. The ‘other’ clearly receives a biased representation: the perpetrators are not Chechen terrorists or Chechen militants but international terrorists. Hence any connection between Russian actions in Chechnya and the Beslan events is invalidated. Consequently, the Russian authorities are cleared of any blame of at least provoking this atrocity. All the blame stays with the terrorists themselves. This constitutes the first fallacy the discourse contains, the fallacy of shifting the issue. Instead of presenting a true picture the speaker provides an interpretation of the events convenient for him.

Another fallacy the argue commits is that of a false dilemma in which a contrary opposition is presented as a contradiction (van Eemeren, Grootendorst 1992: 190). President Putin suggests in paragraph 21 that there appears to be a choice: to strike back or to give in to the demands of terrorists and to allow the terrorists to destroy and split up Russia, hoping that in the end they will leave Russia alone. In 22, he says, however, that in reality Russia simply has no choice: if the Russian Government gives in to the blackmail of the terrorists and start panicking millions of Russians will be plunged into an endless series of bloody conflicts such as the Armenia-Azerbaijan Karabakh conflict or the Moldova-Dniestr conflict. Therefore, only one avenue is open to Russia – hold strong and defend herself. The false dilemma is contained in the assertion that there are only two options that are in contradictory relation to each other: to give up the fight and let the country be destroyed or continue fighting and keep the country from breaking up. However, as opponents of the war in Chechnya point out there may be a third option, quoting at least one example of a peaceful resolution of a deep-rooted violent conflict through negotiations with terrorists, that of the Northern Ireland settlement. The British Government had made several attempts to enter into negotiations with the IRA before finally reaching a compromise that brought peace to Northern Ireland. Northern Ireland has not broken away from the United Kingdom as a result of this; the UK is still a united country. It is this third way – negotiations with terrorists – that is branded by Putin succumbing to the terrorists’ blackmail.

Another fallacy committed by the author is evading the burden of proof by making an argument immune to criticism. Paragraph 18 concludes with a statement We should not turn away from this obvious fact that means that the point made is an obvious one and needs not be defended. Such a statement violates Rule 2 of the critical discussion rules developed in the pragma-dialectical theory of argumentation. “An obvious way of evading one’s own burden of proof is to present the standpoint in such a way that there is no need to defend it in the first place. This can be done by giving the impression that the antagonist is quite wrong to cast doubt on the standpoint or that there is no point in calling it into question. In either case, the protagonist is guilty of the fallacy of evading the burden of proof. The first way of evading the burden of proof amounts to presenting the standpoint as self-evident” (van Eemeren, Grootendorst 1992: 118). As we have already noted, the claim the arguer makes in this paragraph is not self-evident at all.

Another point worth mention in relation to fallacies is a shift of definition in the speech. If we examine paragraph 21 we will see that by the term civil society the speaker understands something different from what his liberal opponents do. For President Putin civil society doesn’t mean an open, self-organized society in which the government is under tighter control of the populace, but rather a society with a vigilant community closely cooperating with law enforcement agencies in preventing terrorist attacks, perhaps through community or vigilante patrols, e.g. the Guardian Angels in New York. Obviously, this shift of definition isn’t a fallacy; rather it is a different interpretation of the term. Thus what would seem at first sight a sign of commitment to democratic values is in effect another argument for the tightening of security in the face of terrorism.

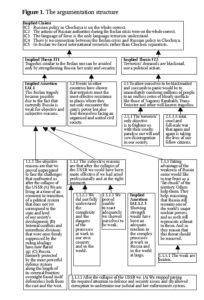

The structure of the argumentation can be represented in the following way:

Let us start our overview of the above figure with an explanation of the different designations applied to the various elements of the argumentation. As you can see from the figure, the argumentation contains two types of statements: expressed statements and implied statements. The latter are divided into Implied Claims, Implied Theses, and Implied Assertions. All these terms basically mean the same thing, an argued statement or point of view, but derive from different traditions of argumentation theory: the terms claim and assertion were introduced by Toulmin working within the framework of Procedural Informal Logic, while the term thesis was introduced by Aristotle belonging to the tradition of Classical Dialectic (van Eemeren et al 2001: 27-47). The purpose of assigning the implicit statements different names is to differentiate them in terms of argumentative importance and the degree of implicitness: ICs are the least apparent statements in the fabric of the message and therefore the justification of ascribing these statements to the speaker can be subjected to doubt more than any other implied statements; while the theses are hierarchically more important than the assertions because the latter are themselves arguments put forward in support of the former. Both the ITs and the IAs are but slightly paraphrased statements that are already available in the discourse.

It is also important to note that the ICs themselves form an argumentation which can be interpreted as leading to any one of them. However, in our opinion the most crucial IC for President Putin is IC1 and thus, it is IC1 that crowns the whole argumentation of the message. As we have already mentioned, Putin is engaged in an implicit debate with those in opposition to his regime over two main accusations. The first accusation concerns his actions during the siege that resulted in so many deaths: had the demands of the terrorists about the withdrawal of Russian troops from Chechnya been met the school would not have been blown up. The second accusation concerns the overall policy in and around Chechnya: it is this policy that has incited the terrorist act. The Russian President’s reasoning develops along two main lines of argument. While the two lines are interwoven, as is shown in Figure 1 in which both lines of argument lead to the same implied claims, and the arguments supporting one line of argument serve the other as well, we can say that the second line of argument is shorter and more clear-cut. It terminates in the text in IT2 and points indirectly to all the ICs but most directly to IC2, IC3 and IC5. The first line of argument is longer and the statements involved in it are better substantiated in the message than those of the first one. The second argumentation terminates in the text in IT1 and while pointing to all the ICs most directly it supports the very important implied claims IC1, IC4 and IC5.

We have already touched upon the evaluation of the two lines of reasoning and pointed out that the first one is weightier than the second. It is precisely the problem with Putin’s argumentation: his apologia is not well enough argued. IC1, IC4 and IC5 are not proven to be the case. They lack solid explicit arguments in the message. However, to make this conclusion we must justify our reconstruction of the implicit elements in the argumentation including the ICs.

In our reconstruction of the structure of the author’s reasoning we followed informal logic’s approach to argument reconstruction, rather than formal logic’s approach, for the following reasons. Van Rees (van Eemeren et al 2001) points out that while both informal logic and formal logic aim to isolate the premises and conclusion of the reasoning underlying an argument, the approaches differ in two major aspects. “First, for informal logicians, deductive validity is no longer necessarily the prime or only standard for evaluating and argument. One of the important issues in informal logic concerns exactly this question of the validity standard to be applied. Most informal logicians hold that some arguments lend themselves to evaluation in terms of deductive validity, while others may be more appropriately evaluated in terms of other standards. This issue has important implications for reconstruction. It means that not all arguments must necessarily be reconstructed as deductively valid. This is especially relevant in the matter of reconstructing unexpressed premises (van Eemeren et al 2001: 180).

For our purposes it means that we don’t seek to fill in missing premises all the time, in all individual arguments (syllogisms) but only where necessary, e.g. in the argumentation consisting of the conclusion 1.1.2 and the premises 1.1.2.1 – IA1.1.2.3. Implied Assertion IA1.1.2.3 is an unexpressed premise that goes together with the explicit premise 1.1.2.3 constituting a single argumentative support for 1.1.2.1. The weakness argument is central to President Putin’s reasoning. In IA1.1.2.3 and especially in the explicit statement And the weak get beaten the speaker emphasizes the necessity of strong action in dealing with Chechen separatists who resort to terrorist attacks on Russian troops and civilians (e.g. in IC3). According to our reconstruction the statement And the weak get beaten lies at the very foundation of a long chain of arguments (1.1.3.1).

“Second, informal logicians view arguments as elements of ordinary, contextually embedded language use, directed by one language user to another in an attempt to convince him of the plausibility (not necessarily the truth) of the conclusion. For reconstruction, this implies taking into account the situated character of the discourse to be reconstructed” (van Eemeren et al 2001: 180).

This aspect is especially important for reconstructing ICs. In doing that we have taken into account not only the immediate context, i.e. the message as it has been spoken, but also a broader context of public debate over Putin’s policy in Chechnya, and therefore, the need for the speaker to present some kind of apologia. The President’s earlier statements concerning terrorism and the conflict in Chechnya (which lies outside the scope of this paper) have informed the above formulations of the ICs.

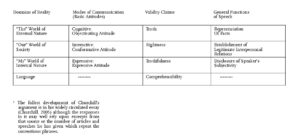

Let us now return to the pragmatic aspect of our analysis. According to the theory of argumentation there are three types of propositions or statements: propositions of fact, value and policy. “These correspond to the most common sources of controversy:

1. disputes over what happened, what is happening, or what will happen;

2. disputes asserting something to be good or bad, right or wrong, effective or ineffective; and

3. disputes over what should or should not be done” (Rybacki, Rybacki 1191: 27-28).

In pragmatic terms propositions of fact and value fall into the same category of utterances performed by way of assertive speech acts and propositions of policy correspond to the category of utterances performed by way of directive speech acts. The argument structure represented above contains exclusively statements of fact and value, of which the latter are only IC1 and IC2. Meanwhile the message contains utterances performed by way directive and commissive speech acts.

Commissive speech acts express the speaker’s intention to commit themselves to a certain course of action. Such acts include pledges, promises, agreements, disagreements etc. A series of measures aimed at strengthening our country’s unity will soon be prepared (24) and I want to stress that all of these measures will be implemented in full accordance with our country’s Constitution (26) are examples of commissives. We must create a much more effective security system and we must demand from our law enforcement agencies action that corresponds to the level and scale of the new threats that have emerged (20) and I think it is necessary to create a new system of coordinating the forces and means responsible for exercising control over the situation in the North Caucasus (25) are examples of directives. In effect, the above directives are indirect commissives through which President Putin informs the country of his commitment to introduce new measures to strengthen Russia’s security.

The pragmatic analysis shows that most speech acts performed in the discourse are assertive and expressive acts. The former include claims, assertions, and statements and the latter include expressions of sympaphy and condolence. Directives and commissives serve an extremely important purpose of confidence building in the discourse. However seemingly insignificant and secondary among the components of the arguer’s communicative strategy they are still a valuable part of it. With the help of all types of speech acts the speaker achieves his objectives: to explain the reasons of the Beslan tragedy, lift the spirits of the people, vindicate his policy in Chechnya and in the Beslan crisis, and justify the proposed reforms in Russia’s governance. To quote President Putin, “And terrorism, of course, is just an instrument to achieve these aims.”

NOTE

i. Project supported by University of Edinburgh, UK and St. Petersburg State University, Russia.

References

Eemeren, F.H., van & R. Grootendorst (1992). Argumentation, Communication, and Fallacies. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Eemeren, F.H., van & R. Grootendorst (2001). Crucial Concepts in Argumentation Theory. Sic Sat, Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Goloubev, V (1999). Looking at Argumentation through Communicative Intentions: Ways to Define Fallacies. In: Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference of the International Society for the Study of Argumentation. Amsterdam: Sic Sat.

Rybacki K., Rybacki D (1991). Advocacy and Opposition. An Introduction to Argumentation. New Jersey.

Strunk, William Jr., White E. B (1979). The Elements of Style. Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc.