Steve Acre – On Fire In Baghdad. An Eyewitness Account Of The Destruction Of An Ancient Jewish Community

Farhud—violent dispossession—an Arabicized Kurdis word that was seared into Iraqi Jewish consciousness on June 1 and 2, 1941. As the Baghdadi Jewish communities burned, a proud Jewish existence that had spanned 2,600 years was abruptly incinerated.

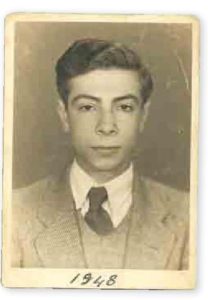

As a nine-year-old, I, Sabih Ezra Akerib, who witnessed the Farhud, certainly had no understanding of the monumental consequences of what I was seeing. Nevertheless, I realized that somehow the incomprehensible made sense. I was born in Iraq, the only home I knew. I was proud to be a Jew, but knew full well that I was different, and this difference was irreconcilable for those around me.

That year, June 1 and 2 fell on Shavuot—the day the Torah was given to our ancestors and the day Bnei Yisrael became a nation. The irony of these two historical events being intertwined is not lost on me.

Shavuot signified a birth while the Farhud symbolized a death—a death of illusion and a death of identity.

The Jews, who had felt so secure, were displaced once again. We had been warned trouble was brewing. Days earlier, my 20-year-old brother, Edmund, who worked for British intelligence in Mosul, had come home to warn my mother, Chafika Akerib, to be careful. Rumors abounded that danger was coming. Shortly after that, the red hamsa (palm print) appeared on our front door—a bloody designation marking our home. But for what purpose?

Shavuot morning was eerily normal.

My father Ezra had died three years earlier, leaving my mother a widow with nine children. I had no father to take me to synagogue; therefore, I stayed home with my mother, who was preparing the Shavuot meal. The rising voices from the outside were at first slow to come through our windows. However, in the blaze of the afternoon sun, they suddenly erupted.

Voices—violent and vile. My mother gathered me, my five sisters and youngest brother into the living room, where we huddled together. Her voice was calming. The minutes passed by excruciatingly slowly. But I was a child, curious and impatient. I took advantage of my mother’s brief absence and ran upstairs, onto the roof.

At the entrance to the open courtyard at the center of our home stood a 15 foot date palm. I would often climb that tree.

When there was not enough food to eat, those dates would sustain us. I expressed gratitude for that tree daily. I now climbed that tree and wrapped myself within its branches, staring down at the scene unfolding below. What I saw defied imagination.

On the narrow dirt road, 400 to 500 Muslims carrying machetes, axes, daggers, and guns had gathered. Their cries—Iktul al Yahud, Slaughter the Jews—rang out as bullets were blasted into the air. The shrieks emanating from Jewish homes were chilling. I hung on, glued to the branches. I could hear my mother’s frantic cries: “Weinak! Weinak!” (Where are you?)

But I could not answer, terrified of calling attention to myself.

The complete story (PDF-format): https://www.mikecohen.ca/files/steve-acre-farhud-article.pdf

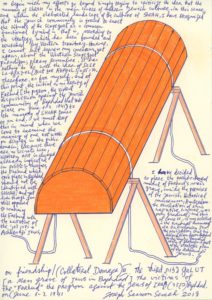

Joseph Sassoon Semah – Working drawing, architectural model mass grave (‘Farhud’, Baghdad, June 1-2 1941). 30 x 21 cm. Paper, blue ink, pencil

Riches To Rags To Virtual Riches: The Journey Of Jewish Arab Singers

Some of the most revered musicians from the Arab world moved to Israel in the 1950s and 60s, where they became manual laborers and their art was lost within a generation. Now, with the advent of YouTube, their masterpieces are getting a new lease on life and new generations of Arab youth have come to appreciate their genius. Part one of a musical journey beginning in Israel’s Mizrahi neighborhoods of the 1950s and leading up to the Palestinian singer Mohammed Assaf.

The birth of the Internet awakens our slumbering memory. Sometime in the 1950s and early 1960s, the best artists from the metropolises of the Levant landed on the barren soil of Israel, from: Cairo, Damascus, Marrakesh, Baghdad and Sana’a. Among them were musicians, composers and singers. It didn’t take them long to find themselves without their fancy clothing and on their way to hard physical work in fields and factories. At night they would return to their art to boost morale among the people of their community. Some of the scenes and sounds which at the time would not have been broadcast on the Israeli media have little by little, been uploaded to YouTube in recent years. Through the fall of the virtual wall between us and the Islamic states, we have been exposed to an abundance of footage of great Arab music by the best artists. This development has liberated us from the stranglehold and siege we have been under, allowing us to reconstruct some of the mosaic of our Mizrahi childhood, which has hardly been documented, if at all.

We should remember that in the new country, as power-hungry and culturally deprived as it was in the 1950s and 1960s, the impoverished housing in the slums of the Mizrahi immigrants was a place for extraordinary musical richness. The ugly, Soviet-style cubes emitted a very strong smell of diaspora. At night, the family parties turned the yards, with the wave of a magic wand, into something out of the Bollywood scenes we used to watch in the only movie theater in our neighborhood. On the table, popcorn and a few ‘Nesher‘ beers and juices. At a Yemenite celebration one would be served soup, pita bread, skhug and khat for chewing, and at that of the Iraqis,’ the tables would have kebabs and rice decorated with almonds and raisins. A string of yellow bulbs, as well as a beautiful rug someone had succeeded in bringing from the faraway diaspora, hung between two wooden poles. There were a couple of benches and tables borrowed from the synagogue, and sitting on the chairs, in an exhibit of magnificent play, were the best singers and musicians of the Arab world.

It is worthwhile to reflect upon those rare times, just before the second generation of Mizrahim began trying to dedicate itself to assimilating in the dominant culture. Those were the days when the gold of generations still rolled through the streets of the Mizrahi neighborhoods and through its synagogues. We should step back for a moment and allow ourselves to look at what we had, what was ours, and what ceased to be ours.

An example of the musical paradise in which we lived can be seen in a video recording from a little later – apparently from the early 1990s. At that time, Mizrahi musicians of all origins were already mingling at each other’s parties, which we see here in a clip of a Moroccan chaflah. The clip, uploaded by Mouise Koruchi, does not tell us where and when the event took place. The musicians in this clip are: Iraqi Victor Idda playing the qanun, Alber Elias playing the Ney flute, Egyptian Felix Mizrahi and Arab Salim Niddaf on violin. One of the astonishing singers is the young Mike Koruchi, tapping the duff and singing with a naturalness as if he never left Morocco, a naturalness that our own generation in Israel has lost. Indeed, it turns out that back then he used to visit Israeli frequently but did not actually live there.

Following him, we see some older members of the community appear on the stage: Mouise Koruchi sings ‘Samarah,’ composed by Egyptian singer Karem Mahmoud; after him comes Victor Al Maghribi, the wonderful soul singer also called Petit Salim (after the great Algerian singer Salim Halali); Mordechai Timsit sings and plays the oud; and Petit Armo (father of the famous Israeli singer Kobi Peretz) rounds out the team. This performance could easily be included in the best festivals in the Arab and Western world, complete with Al Maghribi’s beautiful clothes and the rug at the foot of the stage.

Read more

Riches To Rags To Virtual Riches: When Mizrahi Artists Said ‘No’ To Israel’s Pioneer Culture

Upon their arrival in Israel, Mizrahi Jews found themselves under a regime that demanded obedience, even in cultural matters. All were required to conform to an idealized pioneer figure who sang classical, militaristic ‘Hebrew’ songs. That is, before the ‘Kasetot’ era propelled Mizrahi artists into the spotlight, paving the way for today’s musical stars. Part two of a musical journey beginning in Israel’s Mizrahi neighborhoods of the 1950s and leading up to Palestinian singer Mohammed Assaf. Read part one here.

Our early encounter with Zionist music takes place in kindergarten, then later in schools and the youth movements, usually with an accordionist in tow playing songs worn and weathered by the dry desert winds. Music teachers at school never bothered with classical music, neither Western nor Arabian, and traditional Ashkenazi liturgies – let alone Sephardic – were not even taken into account. The early pioneer music was hard to stomach, and not only because it didn’t belong to our generation and wasn’t part of our heritage. More specifically, we were gagging on something shoved obsessively down our throat by political authority.

Our “founding fathers” and their children never spared us any candid detail regarding the bodily reaction they experience when hearing the music brought here by our fathers, and the music we created here. But not much was said regarding the thoughts and feelings of Mizrahi immigrants (nor about their children who were born into it) who came here and heard what passed as Israeli music, nor about their children who were born into it. Had there been a more serious reckoning from our Mizrahi perspective, as well as the perspective of Palestinians, mainstream Israeli culture might have been less provincial, obtuse and mediocre than what it is today.

Israeli radio stations in the 60s and 70s played songs by military bands, or other similar bands such as Green Onion or The Roosters. There were settler songs such as “Eucalyptus Orchard” with its veiled belligerence, and other introverted war songs, monotonous and stale, inspiring depressive detachment. For example, take “He Knew Not Her Name,” sung here by casual soldiers driving in a jeep through ruins of an Arab village, or the pompous “Tranquility.” When these songs burst out in joy, as is the case with “Carnaval BaNahal,” it comes out loud and vulgar. “The Unknown Squad,” composed by Moshe Vilensky, written by Yechiel Mohar and performed by the Nahal Band in 1958, always reminded me of the terrifying military march music I used to hear on Arab radio stations as a child. As far as the Arabs were concerned, these tunes represented trivial propaganda, not the cultural mainstream. However, in Israel, the Nahal Band was lauded as the country’s finest for more than two decades. Thanks to YouTube, we can now revisit the footage and see them marching, eyes livid and intimidating, faces blank.

Shoshana Damari’s voice, which was supposed to cushion our shocking encounter with this music, only made it worse. Every time her voice would boom out on early 70s public television my father would stretch an ironic smile under his thin Iraqi mustache and let out an expressive, “ma kara?” (“what’s the big deal?”), in sardonic astonishment of the wartime-chanteuse’s bombastic pomp.

It’s not hard to understand why revolutionary Zionists would have their hearts set on a patriotic military musical taste, complete with marching music and Eastern European farming songs fitted for a newfound belligerent lifestyle. But this dominating attitude would prove shocking to Mizrahi Jews, and the musicians among them, who took an active role in the greater Arab music scene (for more on the topic read part one of this series). These musicians were accustomed to the cultural freedoms they enjoyed in the cosmopolitan atmospheres of Marrakesh, Cairo and Baghdad before the military coups. And contrary to popular belief, our ancestors carried no sickles or swords. From Sana’a jewelers to Iraqi clerks under British rule, Persian rug merchants and Marrakesh textile merchants, the majority of Mizrahi Jews lived in urban areas.

In Israel, Mizrahi Jews found a political rule that penetrated all aspects of civilian life, controlling and demanding full obedience even in matters like culture and music. Everyone had to conform to the idealized Sabra figure who sang “Hebrew” music – as in, Eastern European music with Mizrahi touches, celebrating the earth-tilling farmer and the hero soldier. The Broadcasting Authority’s Arab Orchestra, where only an small portion of the musicians were employed and paid meagerly, was established for the sole purpose of broadcasting propaganda to Arab audiences, never with a thought toward domestic consumption.

Patriotic songs that tried going Mizrahi weren’t of any greater appeal. We didn’t get what was so mizrahi about their monotonous drone. On rare occasions, a moving song like “Yafe Nof” slipped through. Written by Rabbi Yehuda Halevi and composed by the talented Yinon Ne’eman, a student of songwriter Sarah Levi Tanai, the song plays like an ancient Ladino tune, sung in Nechama Hendel’s beautiful, ringing voice. The delightful Hendel, who had also been shunned by the cultural establishment for a time, sings the magical Yiddish tune “El HaTsipor” (To the Bird), a diasporic soul tune that occasionally snuck its way on to the radio. At the time, I thought this song seemed more adequate in relation to the sorrows of Ashkenazi Holocaust survivors living in my neighborhood than what “Shualey Shimshon” (Samson’s Foxes) had to offer.

There were exceptions, such as Yosef Hadar’s timeless “Graceful Apple” and the internationally acclaimed “Evening of Roses.” Most of the several-dozen versions of this song circulating on the net were not posted by Israelis or Jews, but rather by music lovers in general.

Daniel Klein ~ The Status And Participation Of ‘Mizrahim’ In Israeli Society

Immediately prior to Israeli independence in May 1948, Jews of non-Ashkenazi origin made up only twenty-three-percent of the 630,000-strong Yishuv. Between 1948 and 1981 757,000 Jews immigrated to Israel from African and Asian countries, 648,000 of these before 1964, and the majority in the first few years of the state’s existence. This initial mass-immigration wave alone transformed the non-Ashkenazi segment of the population from a minority, mostly well-rooted Sephardi community, concentrated especially in Jerusalem, to a highly diversified, mostly first-generation-immigrant grouping that made up a slim majority of all Jews in Eretz Israel. Ben-Gurion referred to these uprooted individuals, who had permanently fled the hostile environment in their home countries, as “human dust” out of which it was the state’s duty to form “a civilised, independent nation”, reflecting the bureaucratic, modernist, and even authoritarian ethos of early Israeli elites.

Immediately prior to Israeli independence in May 1948, Jews of non-Ashkenazi origin made up only twenty-three-percent of the 630,000-strong Yishuv. Between 1948 and 1981 757,000 Jews immigrated to Israel from African and Asian countries, 648,000 of these before 1964, and the majority in the first few years of the state’s existence. This initial mass-immigration wave alone transformed the non-Ashkenazi segment of the population from a minority, mostly well-rooted Sephardi community, concentrated especially in Jerusalem, to a highly diversified, mostly first-generation-immigrant grouping that made up a slim majority of all Jews in Eretz Israel. Ben-Gurion referred to these uprooted individuals, who had permanently fled the hostile environment in their home countries, as “human dust” out of which it was the state’s duty to form “a civilised, independent nation”, reflecting the bureaucratic, modernist, and even authoritarian ethos of early Israeli elites.

The term ‘Mizrahi’ (‘Eastern’) first developed among Ashkenazim as a general descriptor for the non-European ‘edot (communities), owing to the perceived cultural similarity between them, and their lack of overarching, geographically-extended identifiers such as that shared by Ashkenazim. However, we shall see that, in consequence of their shared experience in the new country, a genuinely ‘Mizrahi’-identified bloc emerged in the decades following the great immigration wave, the founding event of this new syncretic ethnic-group. This is the first period I will discuss. The second begins by the 1980s and is characterised by the development of an ‘Israeli-Jewish’ ethnic-group, out of two consolidated (Ashkenazi and Mizrahi) blocs. I will argue that despite confronting harsh challenges in the first period, it is clear today that Mizrahim have affected a substantial long-term reshaping of Israeli society, whilst simultaneously maintaining its core values and stability, thus demonstrating the massive extent of their solidarity and cooperation with fellow Israelis.

The complete paper on academia.edu: https://www.academia.edu/The_Status

Naeim Giladi ~ World Organization Of Jews From Islamic Countries

11-07-94 Original Air Date – Naeim Giladi (Hebrew: נעים גלעדי) (born 1929, Iraq, as Naeim Khalaschi) is an Anti-Zionist, and author of an autobiographical article and historical analysis entitled The Jews of Iraq. The article later formed the basis for his originally self-published book Ben Gurion’s Scandals: How the Haganah and the Mossad Eliminated Jews.

Giladi was born in 1929 to an Iraqi Jewish family and later lived in Israel and the United States.[Giladi describes his family as, “a large and important” family named “Haroon” who had settled in Iraq after the Babylonian exile. According to Giladi his family had owned, 50,000 acres (200 km²) devoted to rice, dates and Arab horses. They were later involved in gold purchase and purification, and were therefore given the name, ‘Khalaschi’, meaning ‘Makers of Pure’ by the Turks who occupied Iraq at the time. He states that he joined the underground Zionist movement at age 14 without his parent’s knowledge and was involved in underground activities. He was arrested and jailed by the Iraqi government at the age of 17 in 1947. During his two years in the prison of Abu Ghraib, he was expecting to be sentenced to death for smuggling Iraqi Jews out of the country to Iran, where they were then taken to Israel. He managed to escape from prison and travel to Israel, arriving in May 1950.

While living in Israel, his views of Zionism changed. He writes that, he “was disillusioned personally, disillusioned at the institutionalized racism, disillusioned at what I was beginning to learn about Zionism’s cruelties. The principal interest Israel had in Jews from Islamic countries was as a supply of cheap labor, especially for the farm work that was beneath the urbanized Eastern European Jews. Ben Gurion needed the “Oriental” Jews to farm the thousands of acres of land left by Palestinians who were driven out by Israeli forces in 1948″.

I organized a demonstration in Ashkelon against Ben Gurion’s racist policies and 10,000 people turned out.”

After serving in the Israeli Army between 1967-1970, Giladi was active in the Israeli Black Panthers movement.

The Meaning Of Galut | On Friendship/(Collateral Damage) III

I went to perform with Joseph Semach in Amsterdam as part of the his art exhibition “On Friendship/(Collateral Damage) III“. His artistic partner Linda Bouws interviewed me about the meaning of “GALUT” (Exile in Hebrew).

Here is my site: https://mati-s.com/