Ella Shohat – Ills.: Joseph Sassoon Semah

When I first contemplated my participation in the “Moments of Silence” conference, I wondered to what extent the question of the Arab Jew /Middle Eastern Jew merits a discussion in the context of the Iran- Iraq War. After all, the war took place in an era when the majority of Jews had already departed from both countries, and it would seem of little relevance to their displaced lives. Yet, apart from the war’s direct impact on the lives of some Jews, a number of texts have engaged the war, addressing it from within the authors’ exilic geographies where the war was hardly visible. And, precisely because these texts were written in contexts of official silencing of the Iran-Iraq War, their engagement of the war is quite striking. For displaced authors in the United States, France, and Israel, the Iran-Iraq War became a kind of a return vehicle to lost homelands, allowing them to vicariously be part of the events of a simultaneously intimate and distant geography. Thus, despite their physical absence from Iraq and Iran, authors such as Nissim Rejwan, Sami Michael, Shimon Ballas, and Roya Hakakian actively participate in the multilingual spaces of Iranian and Iraqi exilic literature. Here I will focus on the textual role of war in the representation of multi-faceted identities, themselves shaped by the historical aftermath of wars, encapsulated in memoirs and novels about Iraq and Iran, and written in languages that document new stops and passages in the authors’ itineraries of belonging.

What does it mean, in other words, to write about Iran not in Farsi but in French, especially when the narrative unfolds largely in Iran and not in France? What is the significance of writing a Jewish Iranian memoir, set in Tehran, not in Farsi but in English? What are the implications of writing a novel about Iraq, not in Arabic, but in Hebrew, in relation to events that do not involve Iraqi Jews in Israel but rather take place in Iraq, events spanning the decades after most Jews had already departed en masse? How should we understand the representation of religious/ethnic minorities within the intersecting geographies of Iraq and Iran when the writing is exercised outside of the Iran-Iraq War geography in languages other than Arabic and Farsi? By conveying a sense of fragmentation and dislocation, the linguistic medium itself becomes both metonym and metaphor for a highly fraught relation to national and regional belonging. This chapter, then, concerns the tension, dissonance, and discord embedded in the deployment of a non-national language (Hebrew) and a non-regional language (English or French) to address events and the interlocutions about them that would normally unfold in Farsi and Arabic, but where French, English, and Hebrew stand in, as it were, for those languages. More broadly, the chapter also concerns the submerged connections between Jew and Muslim in and outside of the Middle East, as well as the cross-border “looking relations” between the spaces of the Middle East. Writing under the dystopic sign of war and violent dislocation, this exilic literature performs an exercise in ethnic, religious, and political relationality, pointing to a textual desire pregnant with historical potentialities.

The Linguistic Inscription of Exile

The linguistic medium itself, in these texts, reflexively highlights violent dislocations from the war zone. For the native speakers of Farsi and Arabic the writing in English, French, or Hebrew is itself a mode of exile, this time linguistic. At the same time if English (in the case of Roya Hakakian and Nissim Rejwan), French (Marjane Satrapi), and Hebrew (Sami Michael and Shimon Ballas) have also become their new symbolic home idioms. In these instances, the reader has to imagine the Farsi in and through the English and the French, or the Arabic in and through the Hebrew. Written in the new homeland, in an “alien” language, these memoirs and novels cannot fully escape the intertextual layers bequeathed by the old homeland language, whether through terms for cuisine, clothing, or state laws specifically associated with Iran and Iraq. The new home language, in such instances, becomes a disembodied vehicle where the lexicon of the old home is no longer fluently translated into the language of the new home—as though the linguistic “cover” is lifted. In this sense, the dislocated memoir or novel always-already involves a tension between the diegetic world of the text and the language of an “other” world that mediates the diegetic world.

Such exilic memoirs and novels are embedded in a structural paradox that reflexively evokes the author’s displacement in the wake of war. The dissonance, however, becomes accentuated when the “cover language” belongs to an “enemy country,” i.e., Israel/Hebrew, or United States/English. The untranslated Farsi or Arabic appears in the linguistic zone of English or Hebrew to relate not merely an exilic narrative, but a meta-narrative of exilic literature caught in-between warring geographies.

Figure 2.1. The recusatio in Persepolis. Image courtesy of Marjane Satrapi, The Complete Persepolis (Pantheon, 2007), p. 142.

Roya Hakakian’s Journey from the Land of No: A Girlhood Caught in Revolutionary Iran and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis both tell a coming-of-age story set during the period of the Iranian Revolution, partially against the backdrop of the Iran-Iraq War. Written by an Iranian of Muslim background (Satrapi) and by an Iranian of Jewish background (Hakakian), both memoirs are simultaneously marked by traumatic memories as well as by longing for the departed city—Tehran. Although the Jewish theme forms a minor element in Persepolis, Satrapi’s graphic memoir does stage a meaningful moment for the Muslim protagonist in relation to her Jewish friend, Neda Baba-Levy. More specifically, it treats a moment during the Iran-Iraq War when Iraqi scud missiles are raining down on Tehran, and where neighborhood houses are reduced to rubble, including the house of the Baba-Levy family. While forming only a very brief reference in the film adaptation, the chapter in the memoir, entitled “The Shabbat,” occupies a significant place in the narrative. Marjane goes out to shop and hears a falling bomb. She runs back home and sees that the houses at the end of her street are severely damaged. When her mother emerges from their home, Marjane realizes that while her own house is not damaged, Neda’s is. At that moment, Marjane hopes that Neda is not home, but soon she remembers that it is the Shabbat. As her mother pulls Marjane away from the wreckage, she notices Neda’s turquoise bracelet. Throughout her graphic novel, Satrapi does display “graphic” images, showing, for example, the torture of her beloved uncle by the Shah’s agents and then by the Islamicist revolutionaries who later execute him. Here, however, the Neda incident triggers a refusal to show what is being expressed in words. After the destruction, Satrapi writes: “I saw a turquoise bracelet. It was Neda’s. Her aunt had given it to her for her fourteenth birthday. The bracelet was still attached to . . . I do not know what..” The image illustrates the hand of little Marjane covering her mouth. In the next panel, she covers her eyes, but there is no caption. The following final panel has a black image with the caption: “No scream in the world could have relieved my suffering and my anger.”[i]

Of special interest here is precisely the refusal to show, a device referred to in the field of rhetoric as recusatio, i.e., the refusal to speak or mention something while still hinting at it in such a way as to call up the image of exactly what is being denied. In Persepolis it also constitutes the refusal to show something iconically, in a medium—the graphic memoir—essentially premised, by its very definition, on images as well as words. Marjane recognizes the bracelet, but nothing reminiscent of her friend’s hand, while her own hand serves to hide her mouth, muffling a possible scream. In intertextual terms, this image recalls an iconic painting in art history, Edvard Munch’s The Scream.

While the expressionistic painting has the face of a woman taken over by a large screaming mouth, here, Persepolis has the mouth covered; it is a moment of silencing the scream. Satrapi represses—not only visually but also verbally—the words that might provide the context for the image, i.e., what Roland Barthes calls the “anchorage” or the linguistic message or caption that disciplines and channels and the polysemy or “many-meaningedness” of the image.[ii] In this case, the caption also reflects a recusatio, in that no scream could express what she is seeing and feeling. As a result, there is a double silence, the verbal silence and the visual silence implied by the hand on the mouth, and then by the hands on the eyes culminating in the black frame image. The final black panel conveys Marjane’s subjective point of view of not seeing, blinded as it were by the horrifying spectacle of war.

Moving from a panel deprived of words to a panel deprived of image, the device goes against the grain of the very medium that forms the vehicle of this graphic memoir. Here, Persepolis evinces a refusal to be graphic in both a verbal and visual sense. We find complementary refusals: one panel gives us the image of a hand over face, of a speechless protagonist where the caption relays her thoughts at the traumatic site of her friend’s bracelet; another gives us covered eyes but withholds the text; and yet another offers no image at all, but gives us a text that relays the impossibility, even the futility, of a scream to alleviate her suffering and anger. The panel that speaks of Neda’s hand shows Marjane’s hand, thus suggesting a textual / visual continuity between the protagonist, whom the reader sees, and the killed friend, whom the reader cannot see. Neda’s death is subjectivized through Marjane’s shock at the horrific sight, allowing the reader to mourn the loss of Neda as mediated through Marjane’s pain.

Although the story of the Baba Levy family is marginal to Persepolis, the intense mourning of the Muslim, Marjane, for the Jewish Neda does not merely represent a traumatic moment for a protagonist; rather, it is crucial in the Bildungsroman. The loss of her friend forms a moment of rupture in the text, which underscores a transformed universe and catalyzes Marjane’s departure and exile. But it is also linked to another traumatic moment in the following chapter, “The Dowry.” In this case, Marjane does not witness but is told by her mother about the loss of another adolescent girl from their family circle, Niloufar, who is taken to prison. As a cautionary tale about the dangers inherent in Marjane’s rebellious actions in school, Satrapi’s mother reminds Marjane that the same Islamic regime that tortured her uncle—just as the Shah regime did—is also the culprit for Niloufar’s fate. The horror of the unfolding story is accentuated by the gesture of whispering: “You know what happened to Niloufar? . . . You know it’s against the law to kill a virgin . . . so a guardian of the revolution marries her . . . and takes her virginity before executing her. Do you understand what that means???”[iii] Through the three dots of the blank space, of the unsaid, as well as through the three question marks for highlighting a rhetorical question, Satrapi implies the de facto rape prior to execution. The fear and love for Marjane lead her family to send her away to Vienna, the only place that would offer her an entry. Marjane’s exile from Tehran and home begins at this critical moment. Between Iraqi scuds over Tehran that make all Iranians vulnerable, and the regime’s war on its citizens, exile becomes the only sensible itinerary for a rebellious adolescent.

“The Shabbat” chapter, which consists of a short sequence of panels revolving around the traumatizing death of Marjane’s friend Neda, precedes “The Dowry” chapter, which relates the death of her communist acquaintance, Niloufar. Both young women are killed—the Jewish friend by Iraqi missiles, and the Muslim communist at the hands of the Iranian regime. Persepolis makes several references to sexual violence.

Already in the section entitled “The Trip,” Satrapi relates this gendered dimension of the memoir at the inception of the revolution and its implementation of the veil. Her mother arrives home distraught after having been stopped while driving without the veil and threatened with sexual violence if she does not obey. Here, Satrapi calls attention to various forms of state violence all represented on a continuum. The threat of rape by the state’s agent is also linked to the very same regime that sends young adolescent boys to war, and that tortures its opponents.

Both chapters, “The Shabbat” and “The Dowry” assign responsibility for the death of two revolutionary republics—the Iraqi and the Iranian.

They precede the Satrapi family’s crucial decision that their daughter must leave Iran at once. Together these two chapters prepare the reader for the inevitable departure, forming a vital crossroad at the beginning of the protagonist’s exilic Odyssey.

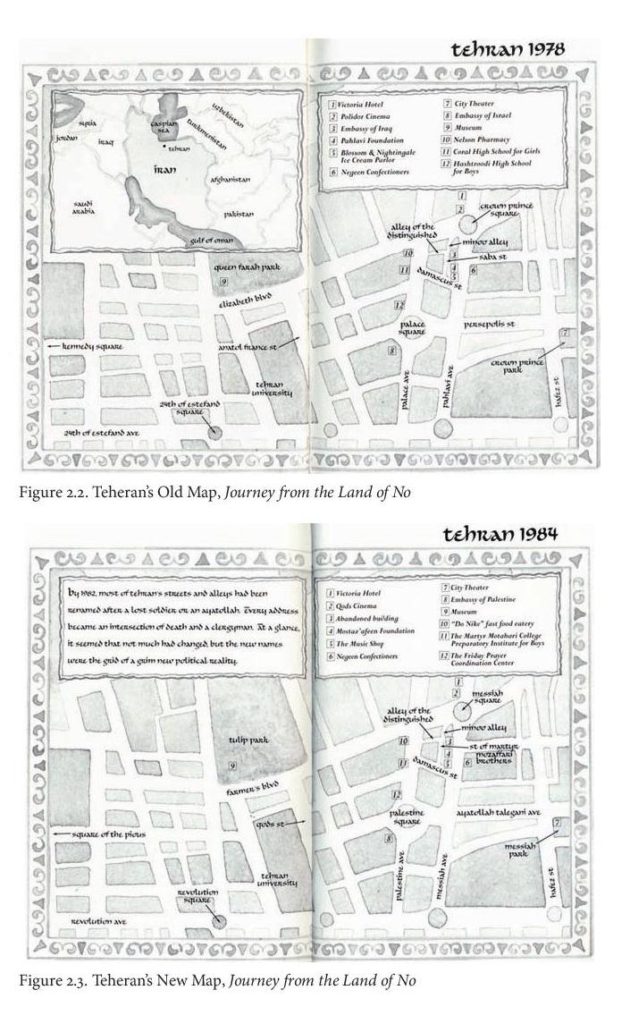

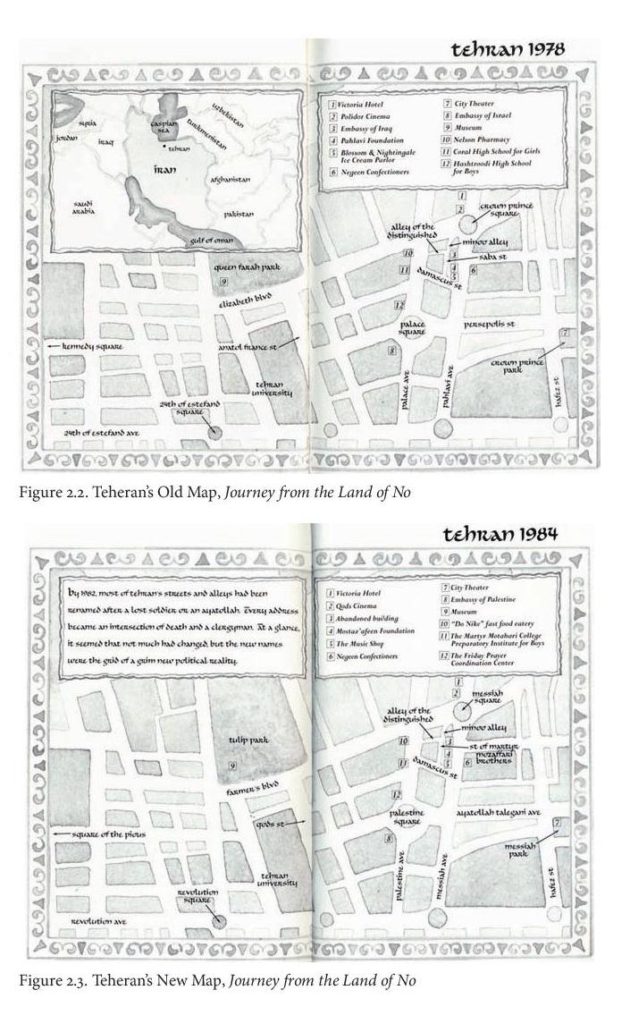

The Iran-Iraq War provokes a remarkable Prise de conscience in the memoirs. Roya Hakakian’s Journey from the Land of No, for example, performs the bifurcated history of Iran visually through two maps that frame her book: one at the very beginning of the memoir, visualizing Tehran of 1978, and the other at the end of the memoir, of 1984 Tehran.

Hakakian compares the names of places on both maps, lamenting the disappearance of her intimately familiar urban environment. She writes:

Yearning for the memories of the old, familiar places, I kept buying maps of the city. One in particular, Map # 255, touted itself “The Most Complete Atlas of the New Tehran: Planned, Produced, and Lithographed by the Geographical and Cartographic Society.” On its upper right corner, a zip code, telephone, fax number, appeared—anything to impress an unknowing customer. Though I knew nothing about cartography, I went about examining this map. I knew Tehran; why be intimidated? Under a magnifying glass, I looked and looked for Saba Street or Alley of the Distinguished, but on the map of the New Tehran, there was no sign of my old neighborhood. The schools where I had studied, the places I had known, everything was either renamed or dropped. Instead of a magnifying glass, I thought, I ought to hold a pen. Instead of maps, I ought to buy notebooks. For those cartographers, geographers, and their fancy societies could not be trusted. And I had to record, commit every detail to memory, in words, what the cartographers had not done in their maps, a testament to the existence of a time and alley and its children whose traces were on the verge of vanishing. [iv]

Hakakian is underlining the renaming of familiar streets after a shahid (martyr), many of whom were children from her own age group, sent to the war with plastic keys to heaven. Their carved names highlight the futile death while also evoking a forever-transformed urban topography.

The question of trauma cathected with a place, then, even in the context of war, is seen through the visual cartography of an intimately familiar and yet thoroughly alien Tehran. Although hardly incorporating visual materials, Hakakian’s memoir does include visual evidence for the erased world. “Number 3: Abandoned Building” on the map is actually the Iraqi embassy, and “Number 8: Embassy of Palestine” indicates the former site of the Israeli Embassy, evidencing two places where deletion and renaming are enacted. Within this context, Journey from the Land of No zooms in, as it were, on the question of Iranian Jews. Hakakian offers a kind of comparison between the position of Jews under the Shah and under Ayatollah regimes. Rather than explicitly criticize these particular re-namings, the text highlights the way lives and dreams have been kidnapped by the war. Ironically, however, all these transformations and comparisons mandate another turn of the translational screw, the act of renaming and translation into English.

In the Journey from the Land of No as well as in Persepolis, one finds a certain nostalgia for the revolutionary moment when social utopia could still be imagined and dreamt about, before the leftist vision was taken away by the Islamic state. Both memoirs reflect the dead end for Iranian leftists persecuted first by the Shah and then by the Ayatollah. In contrast to contemporary Middle Eastern Jewish memoirs that portray a negative image of Islam, Hakakian depicts Tehran as the site of cross-ethnic and cross-religious solidarity for those struggling for democracy and freedom. Like the Iraq in the novels by Shimon Ballas and Sami Michael that I will discuss subsequently, the Iran of Hakakian’s memoir is a space where people of diverse ethnic and religious backgrounds share a utopian desire for an equal multi-faith society. Ballas and Michael’s Hebrew novels about Iraq also similarly manifest a “revolutionary nostalgia” for the era when communism was a thriving ideology, before the party was crushed by successive regimes, culminating with the persecution by the Ba‘ath Party and Saddam Hussein. Although in Ballas’s novel Outcast, Qassem, the communist, is not the protagonist, he nonetheless carries the “norms of the text” through which the various ideological points of view are being evaluated. Outcast thus celebrates the ways in which revolutionaries from different religious backgrounds marched together and fought for democracy, even though the leftists (especially but not exclusively) were tortured by all regimes. Qassem, for example, tried to escape to the Soviet Union because he was about to be executed; but he was then caught by the Shah’s regime, tortured, and handed over to Saddam Hussein and the Ba‘ath Party. Iranian memoirs such as Persepolis and Journey from the Land of No stage the same dead-end situation. In Persepolis, Satrapi’s uncle Anoush is the victim of the same historical double whammy of being tortured first by the Shah and then by the Islamicist regime. These texts portray a world of no exit for those utopianists who fought for equality and democracy, when both Iraq and Iran were crushing movements for social transformations. Iraqi and Iranian exilic literature demonstrates that exile actually begins before the physical dislocation. Prior to their displacement from Iran or Iraq, the leftist characters are depicted as already suffering a kind of internal exile in their own respective countries.

The exilic language simultaneously inscribes the exilic condition while also intimating its possible transcendence. Hakakian, it is worth noting, aspired to write in Farsi rather than in English, and she continues to write poetry in Farsi in the United States. That the memoir is written in English is itself a testament to the fact that the act of narrating Iran, which first takes place in the context of kidnapped leftist dreams in Iran, now takes place in the context of dislocation to the United States, with the narration of Iran now displaced into the English language. Marjane Satrapi, meanwhile, although she grew up in Tehran and spoke Farsi as a first language even while receiving a French education, writes her memoir in French, the language of her new cultural geography. In other words, Satrapi writes about her experience not in the dominant language of her home country—Farsi—but in a European language—French—which in a sense stands in for Farsi, much as English stands in for Farsi in Roya Hakakian’s memoir, or for Arabic in Nissim Rejwan’s memoir, while Hebrew stands in for Arabic in Shimon Ballas’s and Sami Michael’s novels. In these narratives, where the actual exile is narrated in English, French, or Hebrew, the writing itself forms an exilic mode of denial of the possibility of writing in the language of the geographies in which the authors were raised. The linguistic mediation of belonging to a place and the question of homeland entail a move from one linguistic geography to another, yet within this new linguistic zone, the author articulates the dissonance of identities and their palimpsestic emotional geographies. This embedded bifurcation is not, however, simply a loyalty test, as is implied by the axioms of persistent nation-state patriotism. Through the literary act of representing Farsi or Arabic through the medium of another language, these memoirs and novels open up spaces of imaginary belonging that complicate any simplistic equation between a single language and a single identity. At times the memoir’s language is doubly removed, as in the case Rejwan’s The Last Jews in Baghdad, since it is written in Israel about Iraq, but in the English language.

While war generates massive dislocations, ironically, it sometimes indirectly facilitates the reuniting of old friends. One consequence of the Iran-Iraq War, for example, was an opening that enabled members of various exilic groups to reconnect. Even when they ended up in “enemy” countries, feelings of affection, friendship, and love nonetheless persisted on both sides of the war zone. Initially, for example in the case of Iraqi Jews in Israel and their friends in Iraq, even the most rudimentary forms of communication were virtually impossible. Paradoxically, it was a number of negative developments—the repressive measures of the Ba‘athist regime, a series of wars, and especially the Iran-Iraq War—that made it possible for the burgeoning Iraqi diaspora in the West to renew relationships with their Jewish Iraqi friends, including even with those in Israel. Nissim Rejwan’s memoir, The Last Jews in Baghdad: Remembering a Lost Homeland, recounts the close friendships among diverse Iraqis that were disrupted when most Jews had to leave Baghdad in the wake of the partition of Palestine and the establishment of the state of Israel. While the memoir focuses largely on Rejwan’s coming of age in Baghdad, it concludes with the attempts, several decades later, to reconnect with his friends, those whom he has neither seen nor heard from for three or four decades. Toward the end of the memoir, in the chapter titled, “Disposing of a Library,” Rejwan recounts how he discovered the whereabouts of one of his closest Baghdadi friends, Najib El-Mani‘, who formed part of Rejwan’s intellectual literary circle that frequented Al-Rabita Bookshop. When finally Rejwan hears about Najib’s where-abouts, Najib has died of heart failure in London:

After nearly ten more years during which I heard nothing either from or about Najib, a friend sent me photocopies of parts of Al-Ightirab al-Adabi, a literary quarterly published in London and devoted to the work of writers and poets living in exile, mainly Iraqis who found they couldn’t do their work in the suffocating atmosphere of Ba‘ath-dominated Iraq.

To my shock and grief, the first several articles were tributes by friends and fellow émigré writers and intellectuals to the work and the personality of Najib al-Mani’, who had died suddenly of heart failure one night in his flat in London, alone amongst his thousands of books and records of classical music. . . . Feeling the urge to know more about my unfortunate friend and seeing that Najib’s sister Samira was Al-Ightirab’s assistant editor, I wrote her a long letter of condolences and asked her to give me additional information about her brother’s years in exile. Did he die a happy man? Was he married? Lived with someone? Any children? And so on. All I learned from the tributes was that his room was scattered with books and records and papers. Damn the books, I murmured to myself, being then in the midst of a colossal operation aimed at getting rid of some two-thirds of my private library. [v]

In a pre-digital era, when communication only took place through “snail-mail” letters and phone calls, communicating across enemy borders was virtually impossible. Memoirs written about dislocations in the wake of war therefore tend to delve into the details of the “how” one learns about the whereabouts of old friends. Rejwan learns that Najib remained in Iraq throughout the 1950s and ’60s while occupying fairly

high official positions, and only came to London in 1979. Najib left Iraq hoping “for some fresh air” away from the Ba‘athist regime, but with the outbreak of the Iran-Iraq War, his wife, three sons, and daughter could not join him. Two of his sons were sent to the front, which also prevented Najib’s wife from joining him. In his London exile Najib was unable to attend the wedding of his daughter, whose husband left for Holland shortly after their marriage in order to avoid being drafted to serve in the Iran-Iraq War. Najib’s son-in-law, it was discovered later, had married another woman in Holland. The Iran-Iraq War thus sometimes devastated the lives even of those who survived the bombs and destruction. Whereas the 1948 establishment of Israel caused Rejwan’s dislocation from Iraq, it was the Ba‘athist repression and the Iran Iraq War that dislocated Najib al-Mani‘ from Iraq. By the time Rejwan hears about his old friend, it is too late. But he does manage to hear from Najib’s sister, who writes Rejwan about Najib’s last years in London: “He lived alone with his lame cat in a flat in London . . . He died in the company of someone he loved, his open book was on Najib’s chest. Is there anyone better than Proust in situations like these!”[vi]

The Iran-Iraq War turned Najib into a lonely man, shorn of his wife and children, as he was unable to see them. Yet the same Iran-Iraq War that forced him to remain in exile also allowed Iraqis in the UK to communicate directly with old friends in Israel, facilitating Rejwan’s learning of Najib’s unfolding story in exile. The communication between Rejwan and Najib’s sister, Samira, subsequently generates several other enthusiastic reconnections and sometimes actual meetings, between Iraqi Jews from Israel and their exiled Iraqi friends who had moved to Limassol, Cyprus, London, Montreal, or California.

Over Iraq’s tumultuous decades, the diverse waves of departures—whether ethnic, religious, or political in nature—ironically allowed for a re-encounter of the diverse groups of exilic Iraqis. Rejwan’s grief over the death of an old friend is also exacerbated by the exilic melancholia in the wake of the loss of a bygone time and place. The death of his dear friend comes to allegorize Rejwan’s own anxieties about loss and death, triggered by previous multiple losses: the earlier symbolic loss of that friend, even prior to his death, due to Rejwan’s earlier exile from Baghdad; the mediated loss of Iraq through Najib’s exile in the wake of the Iran-Iraq War; the multiple waves of dislocations that led to the dissolution of a religiously and ethnically mixed intellectual circle of friends; and the erasure of the Jewish chapter of Iraqi history as aptly encapsulated by the title of the book, The Last Jews in Baghdad: Remembering a Lost Homeland (emphasis mine). The memoir is written under the sign of loss and dispersal, i.e., the scattering of the Jewish community of Mesopotamia, and ironically the diasporization of “the Babylonian Diaspora.” The Iraqi homeland, no longer available to Iraqi Jews, is also lost for the majority of Iraqi people. Rejwan’s memoir offers an elegy for multiple worlds lost, largely in the wake of the Israel-Arab War but also in the wake of the relatively distant Iran-Iraq War.

The eulogy for the life of Middle Eastern Jews in the context of Islam, explicitly narrated in appendix A of that work, titled, “The Jews of Iraq: A Brief Historical Sketch,” is not merely a coda for Rejwan’s book but

also a final “chapter” for Babylonian Iraqi Jewish history. In this sense, the losses turn individual death into an allegory of communal disappearance, which necessitates the writing of its history, a kind of firm grounding of the past in the text. Yet books themselves are haunted by the possibility of their own disappearance, by the liquidation of an archive. The death of his friend Najib among books is paralleled by Rejwan’s own forced disposal of most of his library, a kind of a metaphorical death for an aging writer forced to part with his beloved life-long book companions. Books may recover communal past but not offer a remedy for loss. The eulogy/elegy is expressed in Rejwan’s words:

So it was Proust that he was reading in his last night—Proust to whose work we had all been introduced as early as the late 1940s and whose Remembrance of Things Past in its English rendering was made available for the first time in Iraq by Al-Rabita Bookshop. Truth to tell, I found myself regretting the scant part I myself had played in Najib’s incessant preoccupation with works of literature—apparently to the exclusion of much else by way of real life.[vii]

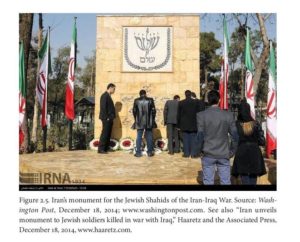

The memoir reflexively evokes Proust’s novel to address “things past” where their “remembrance” (as well their forgetting) takes place not merely within individual-subjective memory but also within communal recollection. To the extent to which Rejwan’s memoir touches on his experiences in Israel, it relates those experiences to those of the Iraqi diaspora displaced elsewhere. In the excerpts of his memoirs published in a London quarterly describing the life of Iraqis in exile in this fashion, Rejwan articulates his displacement experience largely in relation to other displaced Iraqis in the wake of wars not directly linked to Iraqi-Israeli life, i.e., the Iran-Iraq War. Like the evocation of the Iran-Iraq War in Shimon Ballas’s and Sami Michael’s novels, Rejwan’s memoir also goes against the grain of the Zionist metanarrative of aliya to Israel as telos, a narrative that ideologically detaches Iraqi Israelis from their Iraqi emotional geography. Rather than endorse the celebratory trope of the “ingathering of the exiles,” Rejwan firmly places his dislocation within the larger context of the multiple Iraqi dislocations of a broader assembly of oppressed minorities and political groups, whether religious minorities such as Jews, Christians, and Shi‘a Muslims, or political opponents such as communists, liberals, and other anti-regime dissidents. His eulogy is dedicated to a lost world that is not simply and reductively Jewish but rather richly multi-faithed, thus subverting not merely the biblical tale but also the Zionist metanarrative of exile and return to the Promised Land. In this sense, the reference to the Iran-Iraq War is not merely to a coincidental factor in the life of his old friend, Najib, but rather to a major event that also affects the friend’s friend, i.e., Rejwan himself. The Jewish Iranian and Jewish Iraqi novels and memoirs, in sum, highlight Jewish affinities with Iran and Iraq, even in a context where Israel’s unofficial stance toward the Iran-Iraq War (like that of the United States) was ultimately a preference for the war to persist.

Writing an Absence

Shimon Ballas’s Hebrew novel Outcast (Ve-Hu Akher, in Hebrew “And He is an Other,” 1991), written by an Iraqi Jew in Israel, offers a vital sampling of the kinds of tensions and paradoxes arising from war, dislocation, and multiple belongings. Outcast is based on the historical case of an Iraqi Jewish intellectual—Dr. Nissim / Naseem / Ahmed Sousa—who converted to Islam and who remained in Iraq even after the departure of most Iraqi Jews in 1950–51. The novel, set during the Iran-Iraq War, is reflexively written as a posthumously published memoir of the protagonist, Haroun / Ahmad Sousan. While narrated in the first person, the novel “stages” a polyphony of Iraqi voices. The Iran-Iraq War serves as a pretext to discuss the history of Iraq through multiple perspectives, including those of its minorities. The novel is premised on a refusal, in this case the refusal to conform to the Zionist idea or expectation that Iraqi Jews after leaving Iraq would sever themselves politically, intellectually, and emotionally from Iraq as a magnet for identification.

The Iraqi Jewish protagonist, an intellectual writing in Arabic—even though the novel itself is written in Hebrew—has studied the history of Iraq and Islam and converted to Islam, viewing his adopted religion as representing universalism in contrast to his birth religion’s penchant for separatism and particularism. The text thus orchestrates an ongoing debate about the place of Jews within Islam and, specifically, within Iraq. Ballas’s novel, in this sense, clearly goes against the grain of the Zionist master narrative that assumes that arrival in Israel naturally brings with it an end of affective ties to one’s former homeland, especially in the case of an “enemy” homeland.

In the novel, the protagonist’s books, My Path to Islam and The Jews in History, are used by the president—alluding to Saddam Hussein—in order to attack both Israel and Jews, as well as to attack Iran.[viii] One is reminded of the pamphlet, not referenced in the text but reportedly distributed by Saddam Hussein’s government, titled, “Three Whom God Should Not Have Created: Persians, Jews, and Flies.”[ix] Within this view, Jews were traitors, allied from antiquity with the Persians. Seeing himself as the modern heir of King Nebuchadnezzar II, Saddam had bricks inscribed with his name inserted into the ancient remnants of Babylon’s walls.[x] If Nebuchadnezzar destroyed the first temple and exiled the Jews to Babylon, the King of Persia, Cyrus the Great, conquered Babylon, and assumed the title of “King of Babylon,” ending the Babylonian captivity and allowing Jews to return to Jerusalem and rebuild the temple. The Iran-Iraq War, in this sense, became discursively grafted onto the memory of ancient Babylonian /Persian wars, now projected onto the contemporary Arab / Iranian conflict into which modern Jews are interpellated as well. In Outcast, the protagonist Haroun / Ahmad Sousan gets caught up in a political maelstrom where his own words are used in a way that he neither predicted nor approved. He sought a version of Islam that was neither fanatic nor extremist, thus in a sense defending the Shi‘a of Iraq against massacres and oppression by the Sunni elite. At the same time, however, the protagonist did not foresee that what was emerging from Iran was also not the philosophical version of Islam that he was seeking. The two opposing sides in the Iran-Iraq conflict represent two versions of state-controlled intolerance, whether in the hegemonic Sunni modernist secular version of the Iraqi Ba‘ath party, or in the hegemonic Shi‘a religious version of the Iranian state. Neither represents the pluralistic, universalistic Islam of the protagonist’s cosmopolitan vision. In this sense, the novel rejects the sectarian tendencies of two nation-state regimes, within both of which critical intellectuals are “in excess” of their totalitarianism.

Outcast also sheds a skeptical light on the Zionist nation-state version of Jewish religion, not merely in the novel’s content, where Jewish nationalism is debated, but also through the very act of writing about Iraq while in Israel, thus challenging the metanarrative of an Arab “enemy country” by imagining Iraq as a geography of identification for the Hebrew reader. During the Iran-Iraq War, the protagonist Haroun Sousan begins to reflect on the 1941 attacks on the Jews (the farhoud) in conjunction with the present attacks on the Shi‘as. Linking past and present, the memories allow for a multiple cross-religious identification through the hybrid Jew/Sunni protagonist. In other moments in Outcast, the place of the Shi‘a in the Iran-Iraq War comes to allegorize the place of the Iraqi Jew during the Israeli Arab conflict.[xi] Both religious communities are implicitly “on trial” for loyalty and patriotism, even though the war is against an outside force. The conflation of Iraqi Jews with the Zionist enterprise and the Jewish state, and later the conflation of Iraqi Shi‘a with the Shi‘a-dominated Iranian state, place first the Jews and then the Shi‘ites under suspicion, leading to a life of fear and anxiety of being perceived as traitors by the Iraqi state. In Outcast, the protagonist Haroun is not depicted as a heroic figure, a portrayal largely incarnated by the relatively marginal character and friend of the protagonist, the communist Qassem. In one heated moment in the text, taking place in the 1940s but recalled by Haroun during the Iran-Iraq War, Qassem criticizes the protagonist’s critical remarks about his fellow Jews. Evoking his books about Jews in Islam, Haroun Sousan defends his thesis: “I wrote of what I know from the inside.”[xii] Sousan alludes to his experiential knowledge as an Iraqi Jew (prior to his conversion) but Qassem refuses Haroun’s “insider discourse,” stating: “I know Jews from the inside, too. I lived with them. They are great patriots.”[xiii] Haroun replies: “Precisely what I had wished for, that they be patriots.” Qassem however insists: “Don’t try to wiggle out of it . . . You couldn’t find a good word to write about them. And it’s time you replied to the fascist provocateurs. Tell them that Jews have withstood the toughest of trials and proven their loyalty to their homeland.”[xiv] “[T]he real test,” Haroun responds, “is Palestine.” To which Qassem responds: “Palestine? . . . You want them to go to Palestine to fight? Who sold Palestine to the Zionists? They’re fighting for Iraq. We’re all fighting for Iraq!”[xv]

Significantly, in this dialogue it is not the “real” and originary Jew who defends Iraqi Jews, but rather the Muslim leftist. Qassem asks Haroun to admit that his writing presented a biased picture of the Jewish community.[xvi] The words of the leftist Qassem, as suggested earlier, function as the “norms of the text,” the novel’s ideological voice of reason. In a temporal palimpsest, the protagonist’s recollections during the Iran-Iraq War become a mode of exposing discrimination against all minorities and censuring the way dictatorial regimes oppress, repress, and suffocate the spirit of freedom. The time of the Jewish departure from Iraq comes to be viewed retroactively through the prism of massive Shi‘a deportations during the Iran-Iraq War. The novel constructs the issue of homeland and belonging through an implicit analogy. The recollection of the debate about the patriotism of Iraqi Jews takes place exactly at the moment the Iran-Iraq War is unfolding. Thus the question of the loyalty of the Jews in the 1940s evokes the 1980s accusation of Shi‘a’s lack of patriotism especially during the Iran-Iraq War. While the Iraqi Shi‘as were the primary targets during the Iran-Iraq War, they continued to be deported, imprisoned, and killed even after the war ended. Their fate came in the wake of the similar experiences of other ethnic and religious minorities, all accused by the state of treason. Shi‘as, as a community, have been massively dislocated within an Iraqi history that displaced Assyrians, Jews, and Kurds as well, along with diverse political opponents, including communists—all suffering dislocation, imprisonment, and massacre.

Outcast reveals the uneasy closeness of the protagonist to the regime, implicitly undermining the ethno-nationalism of the Ba‘ath regime. The novel deploys the fictional last name of the protagonist “Sousan,” a

name that maintains an intimate proximity with the actual family name of the historical figure “Sousa,” a proximity that, I would argue, casts an ironic light on anti-Persian Arab nationalism. Both names originate from the Persian “Susa” (Sousa) or “Shoush” (Shush), an ancient city of the Elamite, Persian, and Parthian empires of Iran, in the Zagros Mountains and east of the Tigris River. “Shushan,” Shushan (or Shoushan) is mainly mentioned in the biblical book of Esther but also in the books of Nehemiah and Daniel, both of whom lived in Sousa / Shousha during the Babylonian captivity of sixteenth century BCE, where a presumed

tomb of Daniel is located in Shoush area.[xvii] Ballas adds to the family name of the historical figure “Sousa” the letter “n,” turning it into “Sousan,” accentuating the link to the Hebrew biblical pronunciation of the city “Shushan.”[xviii] The name of the protagonist is thus a mixture of the Persian element in the name of the historical figure, the Iraqi Sousa with the Hebrew reference Shoushan, thus emphasizing in Hebrew the allusion to ancient Persia and Babylonia. The mixture of letters in the protagonist’s name blurs the boundary not only between ancient Babylonia and Persia but also between contemporary Iraq and Iran. This palimpsestic blurriness goes against the grain of the purism typical of Iran-Iraq War official propagandas. Indeed, the memoir-within-the-novel of Outcast alludes to the complexity of religious and ethnic identities within Iraq. The protagonist writes: “Our family is one of the oldest in town, and according to one theory its origins lay in Persia, its lineage going back to the celebrated city of Shushan, the very Shushan that figures so prominently in the Book of Esther.”[xix]

The town that the protagonist refers to is Al Hillah, which is adjacent to the ancient city of Babylon and its ruins. It is also near Al Kifl, the site of the tomb of Ezekiel, where Iraqi Jews would go on their annual pilgrimage (‘id al-ziyara), and later had been protected as a holy site by Saddam Hussein. Al Hillah was largely a Shi‘a city and the site of Saddam’s acts of executions and massive graves. Outcast, in this sense, highlights the multilayered history of Iraq, that includes Bablyonians, Persians, Jews, as well as Shi‘a and Sunni, in such a way as to undo any narrow definition of Mesopotamia/Iraq and indirectly of Persia/Iran.

Ironically, that ancient history, encoded, as it were, in the name of the Jewish/Muslim protagonist, challenges the Iran/Iraq nation-state borders that have led to the senseless Iran-Iraq War. The modern Iranian town of Shush is actually located at the site of the ancient city Shushan/Shoushan, in Khuzestan Province, which Saddam Hussein attempted to control during the Iran-Iraq War, claiming that it belonged to Iraq because of its large number of Arabic speakers. Located on the border with Iraq, Khuzestan suffered the heaviest damage of all Iranian provinces during the war, forcing thousands of Iranians to flee. Ballas’s Outcast, which begins with the Iran-Iraq War, thus also undermines the modern ideology of Sunni/ Shi‘a nation-state conflict by alluding to a region that could be seen as simultaneously Persian and Arab, and which includes indigenous Jews and Christians. Millennia of mixing and intermingling from antiquity to the modern era offer evidence of cultural syncretism across the region and beyond. Indeed, this deeper longue durée of Shimon Ballas’s text also reverberates with the historical overtones of Marjane Satrapi’s very title “Persepolis”—Greek for “city of Persians” known in antiquity as Parsa, invaded and destroyed by Alexander the Great, and thus functions as the memoir’s subliminal reminder of the ancient Greek-Persian wars. In 1971, Shah Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi organized festivities for the 2,500-year celebration of the Persian Empire that began with Cyrus the Great. Rather than offering a modern monumental version of antiquity in the style of modern nationalist discourses, Ballas and Satrapi subtly invoke antiquity in order to undermine purist narratives of contemporary identity, including between “East” and “West.” In this sense, the Persians are not only partly Arabs, and vice versa, but they are also partly Greeks.

Published at the time of the 1991 Gulf War between the Allies and Iraq, Ballas’s novel must be read against the backdrop of the Iran-Iraq War, during the period within which it was written and also represents.

Within its historical span, moving from the 1930s to the 1990s, the novel also deals with the antecedents to the Iran-Iraq War and the ongoing political debates in Iraq about Iraqi Shi‘a supporting Khomeini during the period of the Shah. For example, one of the characters, Mostafa, is concerned with the Iranian problem and “the subversive activities of Iranian exiles that were constantly in the headlines.”[xx] Another character, Khalid, meanwhile argues that: “[t]he matter was not as simple as it appeared, because Iraq had not provided a refuge to Khomeini and company out of pure hospitality, but also because we supported his struggle against the Shah.”[xxi] Mostafa, in response, argues: “Struggling against the Shah wasn’t the same as working to establish a Shi’ite Party in Iraq.” And another character, Jawad, concurs and says: “Khomeini was meddling into Iraq’s internal affairs and inciting a war between religious factions.”[xxii] Although Outcast begins with a speech by the protagonist who is honored by the president during the Iran Iraq War, it relays the history of animosity that paved the way for the Iran-Iraq War, as reported in the memoir-within-the-novel:

Events in Iran and reactions in our country have disrupted my writing routine. A fortnight hasn’t gone by since the outbreak of the revolution and already demonstrations against the Iraqi embassy have resumed, as well as allegations that Iraq persecuted Khomeini and was hostile to the revolution. Radio Tehran has launched a series of venomous tirades against Iraq as a collaborator with Israel and the United States, as wanting to reinstate the Shah and drown the Islamic revolution in torrents of blood. One cannot believe one’s ears. Such hatred after fourteen years of living among us? Jawad al-Alawi is not surprised. Khomeini’s expulsion is not the cause of this hate, but the deeply rooted hatred of the Shi‘a. Indeed, that’s how it is, this hostility never died down, but even so one cannot ignore the progressive nature of a revolution that managed to overthrow a rotten monarchy and proclaim a republic. “That is the positive aspect,” agrees Jawad.[xxiii]

In the novel, the Sunnis largely view the Shi‘ite as a “fifth column”[xxiv] although some Shi‘a characters are described as loyal and principled and free of Shi‘ite tribalism.[xxv] However, Ballas is careful to represent multiple Iraqi perspectives on the Iran-Iraq War. The novel stages an ideological, political, and historical debate among diverse Iraqi characters, each one of them representing a different take on post-revolutionary

Iran and its impact on the definition of Iraqi identity. Interestingly, one of the sharpest criticisms of the government is voiced by the protagonist, Haroun Sousan, who is on one level a regime loyalist but who on another level is a critic who wonders if a pro-government supporter had “forgotten the blood bath, two years ago, when the army attacked a procession of pilgrims coming out of Najaf with live ammunition? Has he forgotten the hundreds of detainees and those executed without trial, or tried in absentia because they’re already six feet under? If one cannot condemn the government, why must one praise it? And all the recent arrests, should these, too, be justified?”[xxvi] Ballas here has his Jewish convert to Islam express sympathy with the Shi‘ites under the Ba‘ath regime.

In another moment, the protagonist writes: “I had some sympathy for the Shi‘ites to begin with, as the disenfranchised, not to mention that I grew up among them and naturally felt part of the Ja’afri school of thought, adhered to by my townsmen. The same Shi‘ite group that was one day to become the party established a non-ethnic image by taking Sunnis and even Christians into its ranks.”[xxvii]

At another point, Ballas moves immediately from the description of the 1941 farhoud attack on Iraqi Jews to the persecution of the Shi‘ites during the Ba‘athist era, thus generating a critical sequencing of the

historically disparate moments of the vulnerability of Jews and Shi‘a in Iraq.[xxviii] At the same time, Haroun Sousan does not represent the novel’s ideological center or the “norms of the text,” since Ballas is careful to show that the Iran-Iraq War was used by both regimes as a pretext to repress the left, whether in Iran or in Iraq.[xxix] Within the framework of the novel, the persecution of the Communists seems to traverse the Iran/Iraq battle lines. The novel actually shows that leftists in both countries were vulnerable during the monarchy as well as during the Ba‘athist Republic regime, just as they were vulnerable during the Shah and during the Ayatollah Republic regime.[xxx] This history of the persecution of the communists under the diverse regimes of Iraq and Iran is largely relayed through the character of Qassem, who escapes the Ba‘athist Iraq and, while on his way to the Soviet Union is caught by the Iranian SAVAK, which brutally tortures him, pulling out his fingernails, breaking his ribs and limbs, “before hanging him upside down and scalding his afflicted body with red hot stakes.”[xxxi] Then they send him back to Iraq “in accordance with a pact initiating neighborly friendship between the two countries.”[xxxii] Ballas continues: “He limped along on one leg following the unsuccessful treatment he had gotten for his other broken limb . . . from the SAVAK [who] tortured him because he was a communist who expressed animosity towards the Shah and the mukhabarat because he was a communist who opposed Ba‘athist ideology.”[xxxiii]

The neighborly relations between the Ba‘athist and the Shah regimes, between the mukhabarat and the SAVAK, were later deployed for propaganda purposes by Khomeini, which itself continued the persecution of leftists as emphasized both in Persepolis and in Journey from the Land of No. The fate of communists in both countries is also narrated through a positive grid in Outcast through its emphasis on the network of camaraderie linking Iranian and Iraqi communists.[xxxiv] The idea of ethnic and religious solidarity between Jews and Muslims of Sunni and Shi’a backgrounds goes against the Ba‘athist discourse of unending hate and resentment toward Jews and Persians. Saddam himself, as we have seen, deployed an animalizing trope to yoke the two groups as despicable “flies.” While the novels suggest that the protagonist Sousan remains a kind of loyalist to the Ba‘athist regime, stating that Iraq needs to be defended,[xxxv] the novel itself takes a distant view toward this Ba‘athis rhetoric, instead highlighting the multiple historical violences and dislocations that came long before the Iran-Iraq War.[xxxvi] Exilic leftist Iraqi literature, in other words, tends to highlight the multiplicity that constitutes Iraqi history and culture, staging a polyphony of Iraqi voices, just as exilic leftist Iranian literature tends to register the close network of relationships among Muslims, Jews, and diverse other Iranians.

Forging Imagined Memories

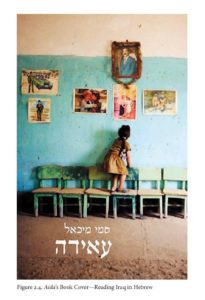

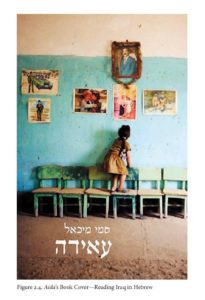

Like Ballas’s Outcast, Sami Michael’s novel Aida is also concerned with the powerlessness of the majority of Iraqi people. At the same time, it is also concerned with cross-ethnic and cross religious solidarities that partially counteract that powerlessness. In Aida, the Jewish protagonist, Zaki Dali, a host of a popular TV documentary show, harbors a Kurdish woman who has been kidnapped, tortured, and raped by agents of the Saddam Hussein regime. As they embark on a romantic relationship, the novel generates a symbolic alliance between an ethnic minority, the Kurds, and a religious minority, the Jews, while also conjuring up a utopian space of interreligious and interethnic romance. Such a romance is especially meaningful in a novel by a former Jewish Iraqi communist, Sami Michael, for whom communism represents more than a political party fighting for sociopolitical and economic equality; it signifies a universalist humanist refuge that transcends ethnic, religious, and nationalist particularities.[xxxvii] The interreligious romance also goes against the grain of the social conventions of the Middle East that decree that marriage takes place within the religious identities into which one is born. While religious communities normally intersected in their commercial, social, and neighborly interminglings, they also carefully monitored interreligious romantic entanglements. Through the mixed romance, Aida offers a “revolutionary nostalgia” toward Iraq’s social-political potentialities. Although written in Hebrew, the language of an enemy country, the novel can be seen as mourning Iraq’s melancholy descent into chaos and civil war. Witnessing dictatorship and even genocide, the Jewish protagonist, Zaki, transports the Hebrew reader into the largely unfamiliar terrain of Iraq of the 1980s and 1990s. “The last Jew,” as the novel often describes the protagonist, mediates between Iraq as remembered by the dislocated Jews and Iraq as experienced over the past three decades. Events in the present evoke incidents in the past, generating a sense of historical repetition, while also re-familiarizing Iraq for its displaced absentees.

Set in the Iraq of the post–Iran-Iraq War, during the 1991 Gulf War that ended with the suppression of the Kurdish and Shi’a uprisings, and during the sanctions period of the following decade, Sami Michael’s novel Aida represents Iraq as a multiethnic and multireligious space.

Apart from the Jewish protagonist Zaki, and the title character, the Kurdish Aida, the novel depicts a close relationship between Zaki and Samia, his Shi’a neighbor and childhood friend. Samia too suffers from the regime’s violence in the wake of the Iran-Iraq War. Her husband, her son, and her pregnant daughter were executed while her remaining two sons have disappeared, listed by the regime as “missing” although the novel reveals that Samia is actually hiding her two sons in the basement, where they live in darkness, cared for by their mother for twenty years.

Every now and then Samia bursts into the offices of the mukhabarat to demand information about the whereabouts of her “missing” sons, a clever ruse to make the police believe in their disappearance and prevent them from searching her house. Secretly Samia marries off one of her sons to a young Shi‘a woman, Siham, who descends into the dark basement and eventually becomes pregnant. Thus, even after the Iran-Iraq War is over, the Shi‘ites continue to suffer at the hand of the regime.

And yet, despite loss and death, the passion for life continues and new life is born. Samia asks her neighbor/friend Zaki to marry Siham in order to protect them by offering a cover for her hidden son and her impregnated daughter-in-law. She tells Zaki he can officially convert to Islam and then divorce Siham, this time using the fact that she is Shi‘a to their advantage, since during the Iran-Iraq War, Sunni husbands were encouraged to abandon their Shi‘a wives, and some did so for crass material interest and the financial benefits offered by the state. Zaki agrees to help Samia for the sake of old neighborly friendship, and also in order to help protect the Kurdish Aida, whom he hides in his house.

The war thus ended up creating spatially bifurcated lives—one lived above ground and the other lived below. Invisibility-as-survival impacts the lives of even the most visible—Zaki’s popularity on television is possible precisely because he is not recognized as a Jew.

Portraying a multi-voiced Iraq of diverse minorities, the novel includes Christian Iraqis as well as diverse Sunni characters. The Christian Rim is an Iran-Iraq War widow who, like most Iraqis, ends up sacrificing for Saddam Hussein’s grandiose war policies. She is portrayed as a sensitive person who would cry at the sight of a cat that had been run over. She sympathizes with the tragedy of her Shi‘a neighbor Samia, but at the same time, Rim regards Samia as the widow of a Shi‘a traitor and the mother of sons and daughters who collaborated with the Ayatollahs of Iran, a situation reminiscent, to her mind, of the descendents of the Persians from centuries before, who fought every Arab regime. The point of view of the Sunni regime is relayed through the eyes of the young Renin, whose mind has been shaped by the Ba‘ath regime since kindergarten. She believed in the mythology of Saddam Hussein as a lion who came to the rescue of humiliated Iraqis under the domination of foreign empires and corrupt rulers but does not question his acts of atrocities. For her, Saddam was only cleansing Iraq’s rotten innards, represented not only by enemies from the outside but also from the inside.

She identifies with the Iraqi leader who forcefully rejected “the influence of the Persians, who connivingly brought destruction and devastation on the empire of Haroun Al-Rashid.”[xxxviii] For Renin, Saddam defends Sunni against the Shi‘a, excelling “in crushing the poisonous snakehead of their agents.”[xxxix] The Caliph Haroun Al-Rashid and his descendents were “innocent rulers,” while Iraq’s present-day leader “is made of armored steel.”[xl] Through the eyes of young Renin, Sami Michael registers the power of Ba‘athist propaganda to instill hatred toward the persecuted Shi‘a majority during the Iran-Iraq War. The multiethnic and multireligious space of the novel Aida, in such instances, relays a dystopic Iraq deeply haunted by the Iran-Iraq War, which despite its official end continues in the attacks endured by the Shi‘a characters.

To counter this propaganda, Michael portrays the devastation brought upon the Shi‘a character Samia, while also invoking other historical moments and figures. In her sorrow, Samia whispers in Zaki’s ear to note the resemblance between Saddam Hussein and the mass murderer of twelve hundred years ago, Al Hajjaj bin Yusef al-Taqafi, who was appointed as the ruler of Najaf, then the most important city in Iraq, and which throughout the years became a holy Shi‘a city. The elders of the city came to greet Al Hajjaj bin Yusef al-Taqafi, but the ruler surveyed them with an expression of scorn and gave an unusual speech that became deeply inscribed in Arabic cultural memory. Full of cruelty, violence, and brutality, al-Taqafi announces his decision regarding who will be killed, and also explains that he will be the person to carry out the mission. The novel presents Samia’s personal and communal pain, like that of Aida, as a kind of a historical recurrence. The very title of the novel, “‘aida,” signifies in Arabic (‘aida) the feminine form of “returnee.”[xli] The Sunni/Shi‘a past haunts the present, and the oppressed cannot escape the tragedy that the Iran-Iraq War brought on them and their family. Yet, recent modern history also seems to repeat itself. The novel narrates Samia’s story in conjunction with that of the Jewish protagonist Zaki. In a kind of return of the repressed, the recent tragedies echo a millennial memory. The deep sorrow and devastation experienced by the Shi‘a are largely mediated through the Jewish protagonist Zaki. Samia and Zaki both lack the comfort of being surrounded by their families, due to different wars and tensions—Zaki, because of the exodus of the majority of Jews, and Samia because of the violent conflict between the Sunni and the Shi‘a. The novel encodes analogical oppressions by shaping a certain parallelism between the devastation wrought on the Jewish community and that wrought on other minorities—the Shi‘a through Samia’s story and the Kurds through Aida’s story. The deep historical connection is allegorized through the novel’s description of the Jewish (Zaki’s) and the Shi‘a (Samia’s) neighboring houses:

The two houses were built by their parents decades ago, attached to each other, and only a low brick fence separated the two roofs, and another fence divided the two gardens. The hopes that were cemented in the foundations and in the walls of the houses faded away in the bitter and violent reality that tormented the country year after year, since then and until now.[xlii]

Zaki’s family was “forced to run for its life” in the beginning of the 1950s with its children dispersed, some to Israel, and some to England and to the United States, while Samia’s family paid dearly for the Shi‘a / Sunni conflict during and in the aftermath of the Iran-Iraq War. The novel describes Zaki and Samia as aging in the absence of their large, close-knit families, living as remnants of a disappearing past. Here too the novel connects the dots between the uprooting (‘aqira) of Jews during the monarchy and the deportation (gerush) of the Shi‘as during the Ba‘athist Republic era.[xliii]

Zaki’s life is simultaneously caught up in the Israeli-Arab conflict and in the Iran-Iraq War, as well as with the Allied war on Iraq. He stayed in Iraq in the name of his first love, his blood-relative Nur, even after his family departed to Israel. Although his love for Nur never reached fruition, he remained in Baghdad because she was buried there, ending up without blood relatives. In the meantime, Nur’s brother Shlomo converts to Islam, now adopting the name Jalil. In contrast to the intellectual protagonist of Ballas’s Outcast, Haroun / Ahmad, who converted to Islam for theological-philosophical reasons, the character of Shlomo / Jalil is portrayed as an addicted gambler who seems to have converted to Islam purely for convenience. Ballas’s convert character Haroun does come under suspicion as an opportunist, when some insinuate: “A Jew doesn’t convert to Islam because the light of truth has penetrated his heart. Don’t tell me such tales!”[xliv] But Outcast ultimately absolves the protagonist of such accusations as a sincere intellectual in search of religious philosophy. The convert in Michael’s Aida, in contrast, is an opportunistic character, even praised by the Ba‘ath leadership. His first wife and young children had to escape to Israel after he left them living in debt. After converting to Islam, Shlomo / Jalil married four war widows in succession during the Iran-Iraq War. Thanks to these marriages, he managed to collect government grants given to married couples in order to encourage men to marry war widows, whose numbers were increasing during the protracted war. He divorced each after obtaining their money, leaving behind him both legitimate and illegitimate children. In contrast to Zaki, who rescues his Shi‘a neighbors by faking marriage to Samia’s daughter-in-law, Shlomo / Jalil represents the corruption of power.

True to its universalist vision, Aida does not idealize any community. Apart from Shlomo’s opportunism, the protagonist Zaki is hardly a heroic idealist figure in the sense of resisting the regime. His patriotic TV program Landscapes and Sites offers homage to a country that witnessed many massacres, and his noble act of saving his Shi‘a neighbor is meaningful, but also forms part of a longer neighborly history of mutual sacrifice. Samia’s father protected Zaki’s family during the farhoud. The novel portrays the complexity of the diverse communities. The Shi‘a Siham, Samia’s daughter-in-law, does not hide her perception of “the Jew” as polluted (nijes), while the Sunni agent of the genocidal regime, the high-ranking mukhabarat officer, Nizar, saves the life of the Jewish protagonist. Such complexities also apply to the war zone between Israel and its neighbors. In a subplot, Michael is careful to portray Iraq and Israel, at the time of the Iran-Iraq War and the Allies’ Gulf War, as places of familial and cultural continuities. The dislocation of Shlomo’s family to Israel is represented in the novel as a matter neither of love for Zion nor of persecution by the Iraqi regime, but merely the consequence of a shaky domestic situation where Israel becomes an alternative for Shlomo’s wife escaping an irresponsible husband. Yet, in an ironic twist of history, the children of Jalil / Shlomo in Israel have kinship relations with the widows of the Iran-Iraq War. As in Ballas’s Outcast, and in Rejwan’s memoir, Michael’s draws a map of biological and emotional continuity of a kind that does not usually register in portrayals of either Israel or Iraq. Zaki’s family experiences the wars within different zones, even enemy geographies. While Zaki remains in Baghdad, his sister lives in Oxford, and his mother lives in Israel, at a time of careening bombs, when the British and Americans are dropping smart bombs on Iraq, and Iraq is sending scuds to Israel. Thus Zaki, in Iraq, while coping with a harsh reality of war, is also concerned about his mother and blood relatives in Israel. In this way, the novel highlights the ironic absurdities inherent in the simplistic notions of “Arab-versus-Jew” and of “enemy countries,” reminding the readers of the dense familial and human connections across borders. Most importantly, the text carries the Hebrew reader into the Iraqi reality-on-the-ground, which during the ’91 Gulf War was largely televised through the aerial point of view of the smart bombs.

True to its universalist vision, Aida does not idealize any community. Apart from Shlomo’s opportunism, the protagonist Zaki is hardly a heroic idealist figure in the sense of resisting the regime. His patriotic TV program Landscapes and Sites offers homage to a country that witnessed many massacres, and his noble act of saving his Shi‘a neighbor is meaningful, but also forms part of a longer neighborly history of mutual sacrifice. Samia’s father protected Zaki’s family during the farhoud. The novel portrays the complexity of the diverse communities. The Shi‘a Siham, Samia’s daughter-in-law, does not hide her perception of “the Jew” as polluted (nijes), while the Sunni agent of the genocidal regime, the high-ranking mukhabarat officer, Nizar, saves the life of the Jewish protagonist. Such complexities also apply to the war zone between Israel and its neighbors. In a subplot, Michael is careful to portray Iraq and Israel, at the time of the Iran-Iraq War and the Allies’ Gulf War, as places of familial and cultural continuities. The dislocation of Shlomo’s family to Israel is represented in the novel as a matter neither of love for Zion nor of persecution by the Iraqi regime, but merely the consequence of a shaky domestic situation where Israel becomes an alternative for Shlomo’s wife escaping an irresponsible husband. Yet, in an ironic twist of history, the children of Jalil / Shlomo in Israel have kinship relations with the widows of the Iran-Iraq War. As in Ballas’s Outcast, and in Rejwan’s memoir, Michael’s draws a map of biological and emotional continuity of a kind that does not usually register in portrayals of either Israel or Iraq. Zaki’s family experiences the wars within different zones, even enemy geographies. While Zaki remains in Baghdad, his sister lives in Oxford, and his mother lives in Israel, at a time of careening bombs, when the British and Americans are dropping smart bombs on Iraq, and Iraq is sending scuds to Israel. Thus Zaki, in Iraq, while coping with a harsh reality of war, is also concerned about his mother and blood relatives in Israel. In this way, the novel highlights the ironic absurdities inherent in the simplistic notions of “Arab-versus-Jew” and of “enemy countries,” reminding the readers of the dense familial and human connections across borders. Most importantly, the text carries the Hebrew reader into the Iraqi reality-on-the-ground, which during the ’91 Gulf War was largely televised through the aerial point of view of the smart bombs.

The Sunni-Iraqis in the novel, meanwhile, are largely represented through the characters of Maher and Nizar, both of whom are friends of the protagonist, Zaki. But while Nizar has a high position in the mukhabarat, Maher resists affiliation with the regime. Throughout the eight years of the Iran-Iraq War, and despite state pressure to abandon Shi‘a wives, he refuses to divorce his wife. He tells Zaki that he would not have replaced his Shi‘a wife with any other family, and certainly not after all the tragedy and killing that they had to face. “The last Jew” of Iraq thus becomes inadvertently embroiled in the ongoing Sunni-Shi‘a conflict. When Nizar visits Zaki’s house, the protagonist feels compelled to warn his neighbor / friend Samia of this visit, in order to protect her.

The novel contrasts the happy party atmosphere in Zaki’s house during Nizar’s visit with the deep sorrow and mourning in the neighboring house of Samia. Here, the novel links the histories of fear and disappearances; the Jews first disappeared from Iraq’s landscape and now, the Shi‘a are in hiding, deported, and “being disappeared.” The Jewish Zaki, meanwhile, can befriend a prominent Sunni mukhabarat person Nizar who insists to Zaki that the Shi‘a “will not rest until the entire Arab world begins to speak Persian.”[xlv] A sense of irony reigns when “the last Jew of Iraq”—a kind of a last of the Mohicans—becomes an unofficial mediator between the Sunni and the Shi‘a. The end of the Iran-Iraq War does not bring relief to the vulnerable Shi‘as. The authorities burn Samia’s house, leading to the deaths of Samia and her family. Zaki’s adjacent house is also destroyed in the process, obliterating a history of neighborly respect and co-existence.

While the Iran-Iraq War haunts all characters in the novel, Aida largely takes place during the sanctions era, beginning with the invasion of Kuwait, the Gulf War, which resulted in the suppression of the Shi‘a and Kurdish rebellions. The novel describes air raids on Baghdad by the United States and British during the early days of the war, with moving descriptions of the consequences of the war “on the ground,” where innocent civilians face hunger, power cuts, intense cold, and the stench of rotting meat in the refrigerator. The novel also inventories the effects of sanctions and the inability to secure needed medicines.

The Sunni Nizar becomes ill and Zaki’s heart weakens and sickens as well. Zaki’s revelation to Aida at the beginning of the novel that “in fact, all I want is to be the last Jew in this place, which they say used to be paradise”[xlvi] does not materialize. Zaki begins to realize that the true motherland is not just a piece of earth but also the woman he loves, and as long as he loved the Jewish Nur, his first love, who was buried in Iraq, he was inextricably bound to Iraq. But after losing Nur, who was tortured in a desert prison and eventually died in Zaki’s arms, he then shelters the Kurdish woman Aida, who was also tortured by the regime yet somehow survived, and finds love with her. The various regimes’ utilization of rape as a weapon, evoked so vividly in Persepolis, is also depicted in Aida, conveyed through the fright of the about-to-be-imprisoned Jewish communist Nur, who, it is suggested, endured multiple rapes, as well as through the present-day repetition of this terrorizing tactic toward the Kurdish Aida. Yet, Nur symbolically returns to Zaki’s life via the Kurdish woman, allowing for Eros to somewhat transcend Thanatos, and the possibility of returning to life. At the end of the novel, Aida, the Kurd, and Zaki, the Jew, fly out of Iraq— though their destination remains unknown—much as Qassem, the communist in Ballas’s Outcast, ends up in exile, having found refuge in Czechoslovakia.[xlvii] In Aida, the departure of “the last Jew” at the end of the novel is interwoven with his flashbacks about his departing family members during the mass exodus of the early 1950s. The present-day dislocations are viewed retroactively as anticipated by past displacements.

The diverse wars—the partition of Palestine in the ’48 war, and the ’67 war, which made the place of Jews impossible in Iraq; the Iran-Iraq War, which made Shi‘a life in Iraq impossible; the ongoing war on the Kurds; along with the U.S. and British war on Iraq—turned Iraq, for its people, into a hellish place from which exile becomes the only possible salvation. Aida however does not end with a separatist view of Iraq, but rather with an allegorical utopia of cross-ethnic and cross-religious solidarity. Like Ballas’s Outcast, Michael’s Aida concludes with the expression of a longing to transcend ethnic religious conflict through humanist universalism. In these novels, both Ballas and Michael, who left Iraq during the mass Jewish exodus of 1950–1951, are not writing about an Iraq of autobiographical memory but rather about the could-have-beens of history, i.e., what might have happened had they stayed in Iraq. In this sense, the authors convey allegories of belonging, where writing about an Iraq of a time in which they never lived becomes a way of expressing a desire to belong to the place they were forced to leave.

The title of Aida also refers to Verdi’s opera, which revolves around the kidnapping of an Ethiopian princess by the ancient Egyptians, an allusion made by the Jewish protagonist in relation to the Kurdish refugee who found shelter in his house. The theme of kidnapping that runs through these texts comes to allegorize the kidnapping of a country in its entirety. For the exilic writer, the depiction of the regime robbing people of their lives forms a mode of solidarity with the unattainable homeland.[xlviii] And in their relative safe haven, these authors produce a literature that conveys their own sense of having been kidnapped from Iraq.

In one of many paradoxical and anomalous situations, both authors who were non-Zionist communists nonetheless ended up in Israel. Yet, through narratives that do not revolve around Iraqis in Israel, or around the Iraq of the 1930s or 1940s, but rather around post–Jewish-exodus Iraq, this exilic literature creates a narrative space through which they come to belong—almost prosthetically, as it were—to an Iraq that was no longer accessible to them. The novels allow for an imaginary affiliation with the revolutionary and anti-dictatorial forces of contemporary Iraq. They vicariously join the anti-totalitarian efforts to overthrow the dictatorial regimes as though continuing their youthful communist thawra (revolution) of their time directed against monarchy, but transposed in the novels into solidarity with the revolutionary opponents of the dictatorship of Saddam’s Ba‘ath party. Setting Outcast during the Iran-Iraq War and setting Aida between the 1991 and 2003 Gulf wars, Ballas and Michael demonstrate clear empathy for the Iraqi people suffering not only from the atrocities committed by the Saddam Hussein regime but also from the Allied war against Iraq. At the same time, both the Iran-Iraq War and later the two Gulf wars come to provide sites whereby the authors can allegorically continue to exist as Iraqis even if in absentia. In sum, these novels and memoirs, all written under the sign and impact of war, orchestrate multiple religious and ethnic voices as a way out of ethnic and religious monologism, as well as out of nationalist xenophobia.

Between Elegy and Eulogy

Through novels set in Iraq, Iraqi-Israeli authors are staking a claim in the debate over the Middle East, and not simply as Israelis. It is as if they were refusing the notion that their departure from Iraq and their move to Israel disqualifies them as legitimate participants in the Iraqi debates about freedom and democracy. From the Iraqi nationalist standpoint, the Jews who left Iraq, even those who did not want to depart, were seen as traitors, and therefore no longer possessing any right or presumably any stake in Iraq. This implicit desire to intervene in Iraq’s debates, even after the massive departure of the Jews, is therefore a mode of reclaiming Iraqi-ness for Arab Jews in exile. The work of Iraqi Israeli writers is thus partially motivated by a desire to assuage a double feeling of rejection; first, from the very place from which they have been physically dislocated—Iraq, and second, from the place to which they were virtually forced to go—Israel. In Iraq, their departure meant a disappearance from Iraqi political affairs and debates, and while in Israel, any pronouncement on Iraq was subject to an alignment with the Israeli “structure of feeling” to an enemy country. Novels such as Aida and Outcast offer an imaginary space for inserting the departed Iraqi Jews back into Iraqi history. They “re-enter” Iraqi geography at a time when Iraq has been rendered unavailable. During the horrifying Iran-Iraq War, their respective novels enact an imaginary return to Baghdad during a tumultuous time of war that scarcely scanned in dominant Israel, unless as a case of two enemy countries (Iran and Iraq) fighting each other in a not entirely unwelcome fratricide, or in the context of the Iran-Contra affair. Indeed, in Outcast, Ballas offers a critique of the Israeli stance toward the Iran-Iraq War, voiced through his Jewish-turned-Muslim protagonist: “A war of Muslims against Muslims, Sunnis against Shi‘ites, could Israel have hoped for anything better?”[xlix] For the Hebrew reader, these words produce an “alienation effect,” defamiliarizing Israel through Jewish Muslim eyes.

The paradoxes and contradictions of Iraqi, Iranian, and generally Middle Eastern Jews in Israel are inadvertently captured in an American film set during the Iran-Iraq War, but which does not concern Israel and Iranian Jews. The 1991 film Not Without My Daughter, adapted from Betty Mahmoody’s memoir, revolves around the experience of an American woman married to an Iranian, who, in 1984, travels with his wife and daughter to visit his family in Tehran, a holiday that turns into a virtual captivity. The memoir/film is set against the backdrop of the Iran-Iraq War, but Brian Gilbert’s film was released during the buildup to the 1991 Gulf War. As Iraqi missiles are falling over Tehran, the mother desperately looks for ways to flee. Finally, she escapes with the assistance of Iranians opposed to the regime, and later with Kurdish smugglers who help her cross the border to Turkey where, in the final scene, Betty and her daughter happily walk to the American embassy and to freedom. While the film does not address the question of Israel, it indirectly embeds the history of dislocation of Jews from Arab and Muslim countries to Israel. Shot in Turkey and in Israel, which stand in for Iran, the film was made with the help of Golan-Globus Studios in Israel. Many of the Iranian and Kurdish characters are actually played by Israeli actors and actresses. This casting practice in fact has a long Hollywood history for its numerous films set in the Arab and Muslim world, for example, Rambo III (1988) and True Lies (1994). In Not Without my Daughter, the cast includes: Sasson Gabay as Hamid; Yacov Banai as Aga Hakim; Gili Ben-Ozilio as Fereshte; Racheli Chaimian as Zoreh; Yosef Shiloach as Mohsen’s companion; and Daphna Armoni as the Quran teacher. Along with the roles of Iranians, the Israeli actors also play the roles of Kurds, speaking in all these roles in a heavy English accent with a Hebrew accent occasionally heard “through” the English-speaking Iranian or Kurdish characters. In one sequence, one of the Kurdish smugglers actually uses a Hebrew phrase, “tov, yallah” (meaning ok, let’s go)—the last word is Hebrew slang borrowed from the Arabic “yallah.” Here, Hebrew, including in its syncretic absorption of colloquial Arabic, stands in for Kurdish.