ISSA Proceedings 2006 – Ehninger’s Argument Violin

Douglas Ehninger’s theoretical gem, “Argument as Method” (1970), introduces us to two unsavory debate characters. First, there is the “neutralist” – an interlocutor who eschews commitment at every turn. Following the Greek philosopher Pyrrho, the neutralist thinks that since nothing can be known, standpoints should float freely, unanchored by the tethers of belief. The neutralist’s counterpart is the “naked persuader” – someone who approaches argument like Plato’s Callicles – clinging doggedly to preconceived beliefs and resisting any shift no matter how compelling the counterpoints (Ehninger 1970, p. 104).

Douglas Ehninger’s theoretical gem, “Argument as Method” (1970), introduces us to two unsavory debate characters. First, there is the “neutralist” – an interlocutor who eschews commitment at every turn. Following the Greek philosopher Pyrrho, the neutralist thinks that since nothing can be known, standpoints should float freely, unanchored by the tethers of belief. The neutralist’s counterpart is the “naked persuader” – someone who approaches argument like Plato’s Callicles – clinging doggedly to preconceived beliefs and resisting any shift no matter how compelling the counterpoints (Ehninger 1970, p. 104).

Naked persuaders and neutralists each have difficulty engaging in argument, but for different reasons. According to Ehninger (1970, p. 104), argumentation is a “person risking enterprise,” and by entering into an argument, “a disputant opens the possibility that as a result of the interchange he too may be persuaded of his opponent’s view, or, failing that, at least may be forced to make major alterations in his own.” In this account, naked persuaders are hamstrung by their unwillingness to risk the possibility that the force of reason will prompt alteration of their views. Neutralists, on the other hand, prevent the “person risking enterprise” from ever getting off the ground in the first place, since they place nothing on the table to risk.

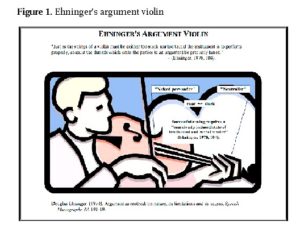

Ehninger’s unsavory characters illustrate how the concept of standpoint commitment has salience in any theory of “argument as process” (Wenzel 1990). To reap the full benefits of the process of argumentation, interlocutors must adopt stances vis-à-vis their standpoints that strike an appropriate balance between perspectives of the naked persuader and the neutralist. For Ehninger (1970, p. 104), such a balanced posture consists of “restrained partisanship,” where advocates drive dialectic forward with tentative conviction, while remaining open to the possibility that the course of argument may dictate that their initial standpoints require amendment or retraction. Finding this delicate balance resembles the tuning of violin strings – a metaphor that underscores his point that the proper stance of restrained partisanship must be tailored to fit each situation.

The public argument prior to the 2003 Iraq War offers a clear example of a poorly tuned deliberative exchange. While several official investigations (e.g. US Commission 2005; US Senate 2004) have explained the breakdown in prewar decision-making as a case of faulty data driving bad policy, this paper explores how the technical concept of foreign policy “intelligence failure” (Matthias 2001) can be expanded to offer a more fine-grained explanation for the ill-fated war decision, which stemmed in part from a failure of the argumentative process in public spheres of deliberation. Part one revisits Ehninger’s concept of standpoint commitment, framing it in light of related argumentation theories that address similar aspects of the argumentative process. This discussion paves the way for a case study of public argument concerning the run-up to the 2003 Iraq War. Finally, possible implications of the case study for foreign policy rhetoric and argumentation theory are considered.

1. Standpoint commitment in argumentation

From a pragma-dialectical perspective, an argument is a “critical discussion” between interlocutors, undertaken for the purpose of resolving a difference of opinion (van Eemeren & Grootendorst 2003, 1984; van Eemeren, Grootendorst & Snoeck Henkemans 1996, pp. 274-311). In the “confrontation stage,” parties lay their cards on the table and establish the central bone of contention. By elucidating their divergent standpoints, disputants provide the impetus that sets into motion the process of critical discussion. This step is essential, since “a difference of opinion cannot be resolved if it is not clear to the parties involved that there actually is a difference and what this difference involves” (van Eemeren, Grootendorst & Snoeck Henkemans 1996, p. 284). However, in pragma-dialectical argumentation theory, once interlocutors advance standpoints, critical discussion norms oblige them to proceed in certain ways. For example, the ninth pragma-dialectical “commandment” requires arguers to retract standpoints if they are refuted in the course of argument, and conversely, to accept successfully defended standpoints offered by their counterparts (van Eemeren & Grootendorst 1992, pp. 208-209).

Here, it becomes apparent that pragma-dialectical theory presupposes the ability of interlocutors to enact a version of Ehninger’s “restrained partisanship.” Arguers are expected to advance standpoints clearly and with conviction, but also to couple this performance with a double gesture that signals a willingness to amend or retract such standpoints should they be refuted during the course of argument. This delicate balancing act challenges participants to find an appropriate middle ground between two poles that have served as perennial topics of inquiry for a wide variety of argumentation theorists.

Consider Chaim Perelman & Lucie Olbrechts-Tyteca’s distinction between “discussion” and “debate.” For Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca (1969), while discussion is a heuristic activity, “in which the interlocutors search honestly and without bias for the best solution to a controversial problem” (p. 37), debate is eristic, where the focus is on “overpowering the opponent” (p. 39), regardless of the truth of the propositions at hand. Occluded in this neat polarity, of course, is the subtle fact that discussion and debate are Siamese twins. They cannot be fully separated without placing the argumentative enterprise at risk. For example, the activity that Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca call “discussion” requires interlocutors to embrace, to some extent, a “debating” posture that moves them to contribute concrete standpoints to the conversation. This caveat does not deny that an overly aggressive debating stance runs at cross purposes with the heuristic goals of discussion, but it does, once again, point to the importance of finding that proper balance that Ehninger calls “restrained partisanship.”

One can isolate other vectors of this pattern playing out in discussions about the proper role of argument in society. For example, the subtitle of Deborah Tannen’s bestseller (1998) The Argument Culture is “Moving from Debate to Dialogue.” Tannen’s distinction between debate and dialogue mirrors Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca’s debate-discussion polarity. While Tannen thoroughly criticizes excessively adversarial and combative styles of debating, she points out that there is still value in constructive forms of argument that allow interlocutors to vet opposing viewpoints (see also Foss & Griffin 1995; Makau & Marty 2001). In fact, she underscored this point by changing the subtitle of The Argument Culture for the paperback edition to “Stopping America’s War of Words” (Tannen 1999).

A similar pattern of analysis appears in the work of James Crosswhite (1996), who posits a distinction between argumentation as “inquiry” and argumentation as “persuasion.” To elucidate the relationship between these categories, Crosswhite (1996, pp. 256-58) compares inquiry with the “context of discovery” and persuasion with the “context of justification” in philosophy of science. In this scheme, argument-as-persuasion involves attempts to convince others of settled beliefs that have already been justified, while argument-as-inquiry is a process of discovery initiated to yield new insights when clear answers may not yet be apparent. As Crosswhite (1996) explains: “There is a difference between the kind of reasoning we engage in when we have already made up our minds about some issue and simply need to persuade other people to take our side, and the kind of reasoning that goes on when we have not yet made up our minds but are trying to come to a conclusion ourselves” (p. 256; see also Meiland 1989). Notably, Crosswhite locates the key difference between these two modes of reasoning in the “kinds of audiences that are active in the argumentation” (Crosswhite 1996, 257).

In pragama-dialectics, this distinction between modes of reasoning is connected to a corresponding differentiation between rhetoric and dialectic. Drawing on Leff (2000), Frans van Eemeren & Peter Houtlousser (2002, pp. 15-17) identify as rhetorical those aims and objectives that interlocutors pursue in their quest to achieve effective persuasion in a critical discussion. Alternately, dialectical obligations flow from the argumentative procedures that parties must respect in order for a critical discussion to proceed. Echoing the other theorists considered in the preceding paragraphs, van Eemeren & Houtlousser develop this polarity synergistically, arguing that rhetoric and dialectic are complementary concepts. If a critical discussion were an airplane, rhetoric would be the force that drives the propeller and dialectic would be the navigational system that keeps the aircraft calibrated and on course. Without a strong propeller (standpoint commitment by interlocutors), the plane cannot get off the ground. Without a sound navigational system (disputants’ fealty to discussion norms), the plane cannot reach the destination point of mutually acceptable resolution of a difference of opinion.

In working out this relationship between rhetoric and dialectic, van Eemeren & Houtlousser have expounded another important concept – strategic maneuvering. This concept stems from their insight that “there is indeed a potential discrepancy between pursuing dialectical objectives and rhetorical aims” (van Eemeren & Houtlousser 2002, p. 16). Arguers want to persuade their counterparts to accept their standpoints, yet the passion driving such commitments may sometimes conflict with the procedural requirements for carrying on a critical discussion. Rather than declare that in these cases, dialectical obligations always trump rhetorical aims, van Eemeren & Houtlousser stipulate that interlocutors have a middle option of strategic maneuvering, a mode of arguing that bends the dialectical rules of critical discussion in a protagonist’s rhetorical favor, yet stops just short of breaking them and thereby committing a fallacy.

For example, in the context of establishing the burden of proof for a given critical discussion, interlocutors may engage in strategic maneuvering by highlighting certain features of their standpoints (e.g. scope, precision, moral content) so as to configure their burden of proof in a rhetorically advantageous way (van Eemeren & Houtlousser 2002, pp. 22-25). However, there are limits to this process. Taken too far, strategic maneuvering moves beyond bending the rules for critical discussion, resulting in a “fallacious derailment” of the discussion (van Eemeren & Houtlousser 2002, pp. 22-25).

While the exact location of this boundary line that separates legitimate strategic maneuvering from fallacious derailment remains elusive, it is clear that the concept of strategic maneuvering represents an inventive response to the theoretical challenge of developing sound accounts of the relationship between “discussion” and “debate” (Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca 1969); “inquiry” and “persuasion” (Crosswhite 1996); and “dialectic” and “rhetoric” (van Eemeren & Houtlousser 2002, pp. 22-25). This same challenge motivates Ehninger’s (1970) effort to explain the complementary relationship between the “naked persuader” and “neutralist” outlined in the introduction to this paper.

Anticipating a key element of pragma-dialectical argumentation theory, Ehninger (1970, p. 102) explains that the speech act of joining an argument involves an implicit agreement that the exchange will exert bilateral influence on the argumentative process. This insight dovetails with his view that argument should be a “person risking” enterprise, and that by entering such an exchange, participants signal that they are ready to place their standpoints in middle space, where tentative commitment drives the exchange, yet is contingent on what transpires in the course of argument. Ehninger (1970, p. 104) elaborates on this posture of “restrained partisanship” by comparing it to the process of tuning a violin: “Just as the strings of a violin must be neither too slack nor too taut if the instrument is to perform properly, so must the threads which unite the parties to an argument be precisely tuned.”

Ehninger’s violin metaphor may provide insight that contributes to pragma-dialectical argumentation theory’s project of delineating the boundary lines that mark off legitimate strategic maneuvering from fallacious derailment. Further insight on this point can be gleaned by considering a specific case study where the issue of standpoint commitment looms large.

2. Prewar public argument on Iraq

The U.S. decision to invade Iraq in 2003 is widely perceived as an “intelligence failure,” in large part because official investigations conducted by a presidential commission (US Commission 2005) and a congressional panel (US Senate 2004) have explained the ill-fated preventive war as a bad policy outcome driven by poor data provided by official intelligence analysts to political leaders. While it is the case that the U.S. Intelligence Community’s prewar analyses on Iraq were imperfect, this is only part of the story. Journalists, citizens, members of Congress and the White House also played key roles in the breakdown. According to Chaim Kaufmann (2004, p. 7), a “failure of the marketplace of ideas” resulted in breakdown of the U.S. political system’s ability to “weed out exaggerated threat claims and policy proposals based on them.” Peter Neumann and M.L.R. Smith (2005, p. 96) call this phenomenon a “discourse failure,” where “constriction of the language and vocabulary” produced a “failure of comprehension.” Elsewhere, I have drawn upon argumentation theory to explain dynamics of this “discourse failure” (see Mitchell 2006; Keller & Mitchell 2006). Here, I isolate a specific element of this phenomenon that has not yet received rigorous scrutiny – derailments in the process of public argument caused by poor tuning of the deliberative exchange with respect to standpoint commitment.

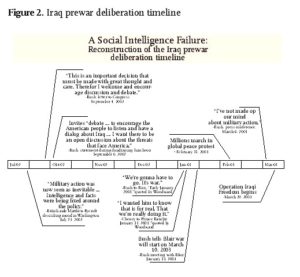

In President George W. Bush’s September, 2002 letter to Congress, he explained that since possible war with Iraq was “an important decision that must be made with great thought and care,” he called for argumentation on the matter: “I welcome and encourage discussion and debate” (Bush 2002a). Bush (2002b) emphasized this point two days later during a fundraising luncheon, inviting “debate” on the Iraq situation, calling for “the American people to listen and have a dialog about Iraq,” and for “an open discussion about the threats that face America.” What exactly did these statements mean? From a pragma-dialectical argumentation perspective, they would seem to constitute “external” evidence that Bush sought to enter into a critical discussion with interlocutors, engaging in argumentation as a way to reach an informed decision on optimal U.S. policy toward Iraq. On this reading, one would expect Bush to proceed as a protagonist in the critical discussion, advancing standpoints, listening to counterarguments, isolating key differences of opinion, and working toward resolution of those differences.

As the first section of this paper established, one key element of this mode of constructive participation in a critical discussion involves tentative standpoint commitment that seeks a middle ground between the postures of Ehninger’s hypothetical interlocutors, the naked persuader and the neutralist. As Ehninger explains further, as disputants search for this middle ground, “investigation not only must precede decision, but is an integral part of the decision-making process” (Ehninger 1959, 284). In other words, a crucial part of an interlocutor’s constructive argument stance involves deferral of a final decision pending completion of the critical discussion. This position has a corollary in pragma-dialectical argumentation theory, where “Rule (9) is aimed at ensuring that the protagonist and the antagonist ascertain in a correct manner what the result of the discussion is. A difference of opinion is truly resolved only if the parties agree in the concluding stage whether or not the attempt at defense on the part of the protagonist has succeeded. An apparently smooth-running discussion may still fail if the protagonist wrongly claims to have successfully defended a standpoint or even wrongly claims to have proved it true, or if the antagonist wrongly denies that the defense was successful or even claims the opposite standpoint to have been proven” (van Eemeren, Grootendorst & Snoeck Henkemans 1996, pp. 285-286).

In the case of President Bush’s argument regarding U.S. policy toward Iraq, Bush’s own statements seemed to express commitment to these principles. After calling for the initiation of a debate on Iraq policy in September 2002, Bush set forth arguments justifying the ouster of Saddam Hussein, but also qualified these standpoints with gestures of “restrained partisanship” (Ehninger 1970, p. 104). For example, during a 6 March 2003 press conference, Bush (2003) stated: “I’ve not made up our mind about military action.”

However, recent disclosure of official documents and insider accounts complicate this picture. We now know that British intelligence chief Sir Richard Dearlove visited the U.S. in July 2002 for meetings where the possibility of war against Iraq was discussed. Regarding developments in Washington, Dearlove briefed Prime Minister Tony Blair on 23 July 2002 that, “there was a perceptible shift in attitude. Military action was now seen as inevitable. Bush wanted to remove Saddam, through military action, justified by the conjunction of terrorism and WMD. But the intelligence and facts were being fixed around the policy.” The memo goes on to say that it “seemed clear the Bush had made up his mind to go to war, even if the timing was not yet decided” (Sunday Times 2005). According to National Security Archive Senior Fellow John Prados, the Dearlove memo shows, “with stunning clarity,” that “that the goal of overthrowing Saddam Hussein was set at least a year in advance,” and that “President Bush’s repeated assertions that no decision had been made about attacking Iraq were plainly false” (Prados 2005). Further evidence in support of this view comes from insider accounts of White House communication during the September 2002 – March 2003 “discussion and debate” period. For example, journalist Bob Woodward explains that while Bush was publicly maintaining a posture of “restrained partisanship” during the public argument on Iraq, he privately told National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice in January 2003 that, “We’re gonna have to go. It’s war” (qtd. in Woodward 2004). Further, Woodward indicates that in another meeting that month, Bush wanted Saudi Prince Bandar “to know that this is for real. That we’re really doing it” (Woodward 2004). A separate leaked British memorandum detailed that later in January 2003, Bush even gave British Prime Minister Blair a specific date (10 March 2003) when he should expect war against Iraq to commence (Regan 2003; see also Sands 2005).

Bearing in mind the tension between speech acts arrayed on the top portion of the timeline in Figure 2 and the speech acts falling in the bottom portion of the timeline, it becomes apparent that Bush’s (2003) statement on 6 March 2003 that “I’ve not made up our mind about military action” was a strategic maneuver, one designed to improve rhetorically his position in the unfolding public argument. The political windfall from such a statement is clear, given the political and military necessity that the decision to invade Iraq be justified on the basis of democratically sound procedures (see Payne 2006). But this returns us to the question that percolated out of the first section of this paper – how should Bush’s strategic maneuvering be classified? Was it a legitimate argumentative move, or a fallacious derailment of a critical discussion, or something else altogether? Considering each possibility in turn provides an opportunity to apply and develop the theoretical concepts regarding the role of standpoint commitment in argumentation.

A charitable interpretation of Bush’s prewar rhetoric would explain the tension between his professed commitments to the process of critical discussion and his early private decision to invade Iraq as the product of legitimate strategic maneuvering, undertaken to enhance the persuasiveness of his standpoint in a critical discussion. In this reading, one might interpret Bush’s private comments to Rice, Bandar and Blair as mere instances of contingency planning designed to prepare the groundwork for execution of a future official decision to attack Iraq. Similarly, Bush’s 6 March 2003 statement that, “I’ve not made up our mind about military action” could be seen as a subtle strategic maneuver designed to add purchase to his rhetorical appeals for war by projecting a generous deliberative posture. The soundness of this line of argumentative reconstruction would hinge on the degree to which it could be established that Bush’s maneuvering stopped short of actually transgressing dialectical rules governing conduct of a critical discussion.

Alternately, it is possible to reconstruct the episode by interpreting Bush’s rhetoric as a fallacious derailment of a critical discussion. In this reading, Bush’s 2002 statements regarding the desirability of debate, discussion and dialogue would be seen as speech acts that set into motion a cooperative process of critical discussion and concomitantly signaled a public commitment by Bush to adhere to certain dialectical rules governing conduct of the public argument (see Payne 2006). As we have seen, one of the key responsibilities of an interlocutor in such a context is to maintain a stance of restrained partisanship vis-à-vis standpoints offered in the course of the critical discussion. However, it is plausible to conclude that such a “middle ground” stance would be impossible for a protagonist such as Bush to maintain in a situation where he had already decided to act on his standpoint (Iraq should be invaded), while simultaneously continuing the critical discussion. On this reading, the excesses of Bush’s rhetoric overwhelmed his commitment to dialectical norms of argumentation, resulting in a fallacious derailment of the critical discussion.

A third possible reconstruction of the episode would proceed from the premise that Bush never actually performed a speech act that signaled commitment to norms of critical discussion. This interpretation would frame Bush’s September 2002 statements regarding the need for “dialogue” and “debate” on Iraq as announcements that a peculiar form of argumentation was about to commence, one perhaps consistent with Ehninger’s (1970, p. 101) model of “corrective coercion.” According to Ehninger, protagonists in this mode operate unilaterally: “Not only does the corrector initiate the exchange and direct it throughout its history, but he also dictates the conditions under which it will terminate.” Furthermore, in corrective coercion, unlike the “person-risking” enterprise of cooperative argumentation, standpoints are not contingent, since failure to persuade interlocutors is an outcome that indicates deficiency in the passive audience, not the standpoint being advocated: “If, in spite of the corrector’s best efforts, the correctee stubbornly continues to resist, the corrector may attribute his failure to a breakdown in communication or an inability to summon the necessary degree of authority; or he may write the correctee off as ignorant or incorrigible” (Ehninger 1970, p. 102). This perspective on the prewar argument reconfigures the relationship between Bush’s public and private statements from one of tension to one of consistency. Arguers engaging in coercive correction need not worry about fine-tuning their degrees of standpoint commitment, since the purpose of the argument is not to test or refine their positions. Here, Bush’s statements to Rice, Bandar and Blair indicating that he had already decided the outcome of the dispute regarding the proper course of U.S. policy toward Iraq can be squared with his public arguments designed to coerce audiences to accept the same view.

The aim of the preceding analysis is not to argue that one particular reconstruction of the argumentative episode is necessarily correct. Rather, the point is to show how argumentation theory generates several possible descriptions of an ambiguous deliberative exchange. Similarly, a robust treatment of the normative implications flowing from each reconstruction falls beyond the scope of this limited paper, whose more modest theoretical contributions are explored in the final section.

3. Conclusion

The relationship between rhetoric and dialectic is moving up the research agenda in argumentation studies (Blair 2002). In pragma-dialectical argumentation theory, the concept of strategic maneuvering is emerging as a bridging concept to elucidate the rhetoric-dialectic interplay. Strategic maneuvering’s value in this regard hinges in part on the degree to which theorists can elucidate perspicacious distinctions between legitimate acts of strategic maneuvering and fallacious derailments of critical discussions. This paper has considered how a focus on standpoint commitment offers a means of generating such distinctions, and how Ehninger’s (1970) notions of “restrained partisanship” and the “argument violin” help to peg the appropriate degree of standpoint commitment in any given argument. Ehninger suggests that for cooperative argumentation to proceed constructively, it is incumbent on interlocutors to seek a “consciously induced state of intellectual and moral tension” that fine-tunes, like violin strings, their rhetorical aims and dialectical obligations (p. 104; see also Ehninger & Brockriede 1966).

Application of these theoretical concepts to a case study concerning public argument prior to the 2003 Iraq War yielded several insights. Most basically, the attempt to reconstruct the prewar public argument highlighted the salience of Gerald Graff’s (2003, p. 88) observation: “Which mode we are in – debate or dialogue? – is not always self-evident.” External cues apparently signaling an interlocutor’s commitment to the process of critical discussion may take on different meanings when viewed in the context of subsequent strategic maneuvering. For example, one possible reconstruction of George W. Bush’s contributions to the prewar public argument on Iraq reveals that his utterances expressing commitment to processes of “debate” and “discussion” signal something very different from the sorts of speech acts that in pragma-dialectical argumentation theory indicate an interlocutor’s implied acceptance of critical discussion norms. This possibility serves as a reminder that in generating argumentative reconstructions, critics should be keenly aware of the possibility that they are dealing with mixed disputes, where parties approach the argument from incommensurate normative assumptions regarding proper conduct of the dispute. The lucid exchange between James Klumpp and Kathryn Olson following Klumpp’s keynote address at the 2005 Alta Argumentation Conference illustrates the value of this critical approach.

Finally, my paper provides an occasion for scholars of argumentation to take note of the trend that the argumentation is growing in prominence as a category of analysis in the field of international relations. Consider Douglas Hart and Steven Simon’s proposition that one major cause of the intelligence community’s misjudgments on Iraq was “poor argumentation and analysis within the intelligence directorate.” As a remedy, Hart and Simon recommend that intelligence agencies encourage analysts to engage in “structured arguments and dialogues” designed to facilitate “sharing and expression of multiple points of view” and cultivate “critical thinking skills.” This suggestion comes on the heels of political scientist Thomas Risse’s (2000, p. 21) call for international relations scholars to focus more on “arguing in the international public sphere.” These comments, coupled with the finding of this paper regarding the need to “rhetoricize” the technical concept of “intelligence failure,” suggest promising paths of future research that fuse parallel tracks of argumentation theory and international relations scholarship.

References

Blair, J.A. (2002). The relationships among logic, dialectic and rhetoric. In F.H. van Eemeren, J.A. Blair, C.A. Willard & F.S. Henkemans (Eds.), Proceedings of the Fifth Conference of the International Society for the Study of Argumentation (pp. 125-131). Amsterdam: SicSat.

Bush, G.W. (2002a). Bush letter: ‘America intends to lead.’ CNN, 4 September. <http://www.cnn.com/2002/ALLPOLITICS/09/04/bush.letter/>.

Bush, G.W. (2002b). Remarks at a luncheon for representative Anne M. Northup in Louisville, September 6, 2002. Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents 38, 1498.

Bush, G.W. (2003). President George W. Bush discusses Iraq in national press conference. 6 March. <http://www.whitehouse.gov>.

Crosswhite, J. (1996). Rhetoric of Reason: Writing and the Attractions of Argument. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

Eemeren, F.H. van & R. Grootendorst. (1984). Speech Acts in Argumentative Discussions. Dordrecht: Foris.

Eemeren, F.H. van & R. Grootendorst. (1992). Argumentation, Communication, and Fallacies: A Pragma-Dialectical Perspective. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Eemeren, F.H. van & R. Grootendorst. (2003). A Systematic Theory of Argumentation: The Pragma-Dialectical Approach. London: Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Eemeren, F.H. van, R. Grootendorst & F. Snoeck Henkemans. (1996). Fundamentals of Argumentation Theory. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Eemeren, F.H. van & P. Houtlosser. (2002). Strategic maneuvering with the burden of proof. In F.H. van Eemeren (Ed.), Advances in Pragma-Dialectics (pp. 13-28), Amsterdam: SicSat.

Ehninger, D. (1959). Decision by debate: A re-examination. Quarterly Journal of Speech 45, 282-287.

Ehninger, D. (1970). Argument as method: Its nature, its limitations and its uses. Speech Monographs 37, 101-10.

Ehninger, D., & W. Brockriede. (1966). Decision by debate. New York: Dodd, Mead, and Co.

Foss, S. & C.L. Griffin. (1995). Beyond persuasion: A proposal for an invitational rhetoric. Communication Monographs 62, 2-18.

Graff, G. (2003). Clueless in Academe: How Schooling Obscures the Life of the Mind. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Hart, D. & S. Simon. (2006). Thinking straight and talking straight: Problems of intelligence analysis. Survival 48, 35-60.

Kaufman, C. (2004). Threat inflation and the failure of the marketplace of ideas: The selling of the Iraq War. International Security 29, 5-48.

Keller, W.W. & G.R. Mitchell (2006). Preventive force: Untangling the discourse. In W.W. Keller and G.R. Mitchell (Eds.), Hitting First: Preventive Force in U.S. Security Strategy (pp. 239-263). Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Leff, M. (2000). Rhetoric and dialectic in the twenty-first century. Argumentation 14, 251-254.

Makau, J.M. & D.L. Marty. (2001). Cooperative Argumentation: A Model for Deliberative Community. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press.

Matthias, W.C. (1991). America’s Strategic Blunders. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Meiland, J. (1989). Argument as inquiry and argument as persuasion. Argumentation 3, 185-96.

Mitchell, G.R. (2006). Team B intelligence coups. Quarterly Journal of Speech 92, 144-173.

Neumann, P.R. & M.L.R. Smith (2005). Missing the Plot? Intelligence and discourse failure. Orbis 49, 95-107.

Payne, R. (2006). Deliberate before striking first? In W.W. Keller and G.R. Mitchell (Eds.), Hitting First: Preventive Force in U.S. Security Strategy (pp. 115-136). Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Perelman, C., & Olbrechts-Tyteca, L. (1969). The New Rhetoric: A Treatise on Argumentation (J. Wilkinson & P. Weaver, Trans.). Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

Prados, J. (2005). Iraq: When was the die cast? Tom Paine Commentary, 3 May. <http://www.tompaine.com/articles/iraq_when_was_the_die_cast.php>.

Regan. T. (2003). Report: Bush, Blair decided to go to war months before UN meetings. Christian Science Monitor. February 3.

Risse, T. (2000). Let’s argue! Communicative action in world politics. International Organization 54, 1-39.

Sands, P. (2005). Lawless World: America and the Making and Breaking of Global Rules from FDR’s Atlantic Charter to George W. Bush’s Illegal War. New York: Viking.

Sunday Times (Britain). (2005). The secret Downing Street memos. 1 May. <http://www.timesonline.co.uk/article/0,,2087-1593607,00.html>.

Tannen, D. (1998). The Argument Culture: Moving from Debate to Dialogue. New York: Random House.

Tannen, D. (1999). The Argument Culture: Stopping America’s War of Words. New York: Random House.

United States Commission on the Intelligence Capabilities of the United States Regarding Weapons of Mass Destruction. (2005). Report to the President. <http://www.wmd.gov/report/>.

United States Senate Select Committee on Intelligence. (2004). Report on the U.S. Intelligence Community’s Prewar Intelligence Assessments on Iraq. <www.intelligence.senate.gov/ iraqreport.pdf>.

Wenzel. D. (1990). Three perspectives on argument: Rhetoric, dialectic, logic. In J. Schuetz and R. Trapp (Eds.), Perspectives on Argumentation: Essays in Honor of Wayne Brockriede (pp. 9-26), Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press.

Woodward, B. (2004). Woodward shares war secrets. 60 Minutes Transcript. 18 April. <http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2004/04/15/60minutes>.