ISSA Proceedings 1998 – Argumentation And Children’s Art: An Examination Of Children’s Responses To Art At The Dallas Museum Of Art

Until recently, relatively little attention has focused on the role of argument in the visual arts. In the last few years, however, and concurrent with the attention given to argument in other disciplines, argumentation scholars have begun to theorize about the intersection of argument and art. In 1996, a special edition of Argumentation and Advocacy examined visual argument, with essays that speculated about the argumentative functions in visual art and political advertisements. In their introductory essay to that special edition, David Birdsell and Leo Groarke write: In the process of developing a theory of visual argument, we will have to emphasize the frequent lucidity of visual meaning, the importance of visual context, the argumentative complexities raised by the notions of representation and resemblance, and the questions visual persuasion poses for the standard distinction between argument and persuasion. Coupled with respect for existing interdisciplinary literature on the visual, such an emphasis promises a much better account of verbal and visual argument which can better understand the complexities of both visual images and ordinary argument as they are so often intertwined in our increasingly visual media (Birdsell & Groarke 1996: 9-10).

Until recently, relatively little attention has focused on the role of argument in the visual arts. In the last few years, however, and concurrent with the attention given to argument in other disciplines, argumentation scholars have begun to theorize about the intersection of argument and art. In 1996, a special edition of Argumentation and Advocacy examined visual argument, with essays that speculated about the argumentative functions in visual art and political advertisements. In their introductory essay to that special edition, David Birdsell and Leo Groarke write: In the process of developing a theory of visual argument, we will have to emphasize the frequent lucidity of visual meaning, the importance of visual context, the argumentative complexities raised by the notions of representation and resemblance, and the questions visual persuasion poses for the standard distinction between argument and persuasion. Coupled with respect for existing interdisciplinary literature on the visual, such an emphasis promises a much better account of verbal and visual argument which can better understand the complexities of both visual images and ordinary argument as they are so often intertwined in our increasingly visual media (Birdsell & Groarke 1996: 9-10).

Although there is no consensus as to whether or not there should be a theory of visual argumentation, the attention given to the concept in this special issue merits further consideration.

The parallels between the fields of art and argumentation are striking. Both are concerned with the theoretical and the practical. Argumentation is concerned with the philosophical underpinnings of the making and interpreting of arguments, as well as the practical side of teaching the construction of arguments for others’ consumption. Art also must be concerned with the philosophy of the interpretation and construction of art works, as well as the practical and pedagogical aspects of teaching students to create art. Participants in both fields are also involved in the critical process, with the concomitant responsibility of speculating about the development of critical approaches and methodologies. Finally, and most relevant to this study, both are concerned with the realm of the symbolic.

In 1997, an exhibition at the Dallas Museum of Art celebrated the role of animals in African Art. Particular works in this exhibition were supplemented with “imagination stations,” or sketchbooks with colored pencils, which allowed children to draw their reactions to this art. Children were guided by instructions developed by the education staff at the museum. These instructions asked the children to describe their reactions to the art and to put it into a context specific to their own backgrounds, such as asking the children to draw an animal that they were familiar with in a similar context to the one in the artwork. These sketchbooks were collected by museum staff, and provide the textual basis for this study.

This essay takes as its point of departure the assumption that visual art can be studied as argument. Although that assumption is certainly debatable, this essay begins by reviewing the literature and constructing three related argumentative roles for visual art. The essay, in its second stage, describes the role of the museum as amplifier and intensifier of these argumentative roles. In the third stage, the essay describes the children’s responses as detailed in the sketchbooks, and speculates about the role that such a participatory exercise might have for the fields of art and argumentation. Finally,the essay concludes with conclusions about the impact of this study on the nature of criticism in art and argument in general. In 1994, at the Third Conference of the International Society for the Study of Argumentation, speculation about the function of argumentation in the post-Cold War era continued. James Klumpp, Patricia Riley, and Thomas Hollihan concluded that, “argumentation scholars have considerable work to do to escape these constraints. But the reward for that effort can be a renewal of democratic values of broad participation in a texture of argument that empowers people to participate in the formation of their lifeworld” (Klumpp, Riley, & Hollihan 1994: 328). This essay begins the search for one potential participatory avenue.

1. Art and Argumentation

While the special issue of Argumentation and Advocacy might be the most comprehensive body of literature dealing with argumentation and visual art, it is certainly not the first. Over the last eight years, there have been several projects that examined art from a rhetorical or argumentative perspective. Ken Chase, in his essay on argument and beauty, describes in significant detail the relationship between argument and beauty. In his examination of Mary Cassatt’s Breakfast in Bed, Chase advances an expanded view of argument, one that broadens argument to include arguments that are not linear sequences of propositions. Chase concludes that “Arguers can be artists, bringing the harmony, unity and symmetry of beauty to bear on the rough edges and fractured relationships of everyday disputes” (Chase 1990: 271). Chase grounds his assessment of Cassatt’s work in the classical and neo-classical works relating rhetoric to the beautiful and the sublime, and does not deal with the rationale for and the implications of bridging argument and art.

Barbara Pickering and Randall Lake, in their examination of the refutational value of films dealing with abortion, find that visual representations can serve an argumentative function. They believe that, “images, even though they are not propositional and hence lack the capacity, strictly speaking, to negate, nonetheless may be said to `refute’ other images” (Pickering & Lake 1994: 142). Pickering and Lake ground their work in the writings of Susanne Langer and Kenneth Burke, who are particularly concerned with images and symbolic constructions of meaning.

The 1996 issue of Argumentation and Advocacy explores the theoretical rationale and implications of expanding conceptions of argument to include visual argument. There are three basic questions involved in the examinations of the four relevant essays (Birdsell & Groarke, Fleming, Blair, and Shelley).

First, must arguments be constructed of words? Shelley distinguishes between what can be referred to as rhetorical or demonstrative visual argumentation. Rhetorical communication is that visual communication which is related to informal verbal arguments. Elements in paintings or pictures would have to have some correspondence to informal verbal argument in order to advance a rhetorical visual argument. Demonstrative visual arguments “represent the actual course of visual thought. Thinking often involves the use of mental images, a process typified by thinking with visual mental images, or the ‘mind’s eye’.” (Shelley 1996: 60). Blair contends that argumentation should not be limited to verbal communication. He writes, “the fact and the effectiveness of visual communication do not reduce it to verbal communication” (Blair 1996: 26). Fleming believes that visual communication can serve as evidence or support for a linguistic claim, potentially provided by a caption or some other verbal statement (Fleming 1996: 19).

Second, are arguments exclusively made up of propositional statements, composed of data and claim? Fleming believes that, to be an argument, something must have a two-part structure (data/claim), and that it must be refutable or contestable (Fleming 1996: 13). Fleming concludes that pictures lack the structure to make them akin to verbal discourse. He writes, “a picture unaccompanied by language lacks the two-part conceptual structure of argument. Second, while it may be able to function as evidence, a picture is incapable of serving independently as an assertion” (Fleming 1996: 15-16). Given this ambiguity, the visual argument becomes impossible to refute, which means that it cannot meet the traditional tests of arguments. Blair believes that visual arguments can occur, and that they must be propositional. He writes: Visual arguments are to be understood as propositional arguments in which the propositions and their argumentative function and roles are expressed visually, for example by paintings and drawings, photographs, sculpture, film or video images, cartoons, animations, or computer-designed visuals (Blair 1996: 26). Blair concludes that other forms of discourse, such as metaphors and narratives, are either propositional or they are not argumentative (Blair 1996: 35). The implication of this interpretation, therefore is to admit the possibility of visual constructions serving as arguments, but to definitionally exclude a significant portion of visual communication from within this scope.

Third, what is the implication of expanding the scope of argumentation to include visual arguments? Fleming believes that a conception of argument could be developed that would include visual argument, but that the new conception of argument would be so vague that it would lose its explanatory potential (Fleming 1996: 13). Blair agrees with this claim, noting that, “it would be a mistake to assimilate all means of cognitive and affective influence to argument, or even to assimilate all persuasion to argument” (Blair 1996: 23), even though he admits that there are still some visual constructions which can function as arguments.

To account for definitive answers to these questions is difficult, but it seems that most of these concerns are true for other, more traditional, forms of argument as well. Verbal arguments can be just as ambiguous as nonverbal or visual arguments, and in some cases, more ambiguous (Birdsell & Groarke 1996: 2). Art can also provide visual cues as to possible propositional arguments, through the implied claims and evidence provided in the particular artwork. To limit the study of argumentation to traditionally propositional is somewhat artificial, and would clearly serve to inscribe one appropriate form for argument. Finally, to expand the scope of argumentation is not particular to the visual; indeed, argumentation has expanded its own reach to include such forms as science, history, and movies. To expand argumentation is not a particularly persuasive reason to exclude the study of one of the most persuasive arenas of all time. Birdsell and Groarke write: Most importantly, it allows for a significant expansion of the theory of argument. Without this expansion, argumentation theory has no way of dealing with a great many visual ploys that play a significant role in our argumentative lives – even though they can frequently be assessed from the point of view of argumentative criteria (Birdsell & Groarke 1996: 9). Given this discussion, it seems appropriate to discuss some of the argumentative functions of argument in art. The next section of this essay begins this discussion, by providing three interrelated argumentative functions of visual art.

2. Art Functioning as Argument

We believe that there are three interrelated functions that visual argument can perform. Initially, art can serve a cognitive or knowledge-based function. Art serves to provide information to its viewers. Viewers seek out art to see how artists have interpreted different persons, places, times, and contexts. Shelley, for example, notes that the interaction between the art and the viewer is principally a cognitive one. Shelley writes, “A step towards such a characterization can be taken by making the distinction between rhetorical and demonstrative modes of visual argument. Fundamentally,this distinction is a cognitive one and concerns how individual elements of a picture are understood by a viewer” (Shelley 1996: 67).

Much of the research about art and argument has examined the art from this perspective. In particular, most traditional argument research is concerned with the elucidation and examination of the claim in a particular artwork, as well as the supporting material. This functional perspective concentrates on the art as a cognitive claim, one which principally examines the artwork in terms of the information that it provides about the subject matter.

Second, art serves to advance normative claims. Particularly for some audiences, art attempts to describe how things portrayed in the artwork should appear, or how things referred to in the artwork should relate to one another. Joli Jensen describes this perspective, arguing: Under this perspective, the people become a substrate on which culture can work. The “bad” cultural choices of the people, so distressing to social critics, are due to the hypnotic or corrupting powers of bad art, or to the lack of exposure to good art. By this logic, the “good” cultural choices of critics and intellectuals are to be protected against the corrosive tide of the people’s choices, so that the people, later, can benefit. Notice how the people are presumed to have, but are never blamed for, corrupted taste and bad judgment that can lead to crass actions and foolish choices. Bad art is a cause, and good art can be a cure, for whatever is deemed to be wrong with the populace (Jensen 1995: 365).

Finally, art serves an ideological function. Art helps people to understand the relationship between people (including the viewer), the state, power in general, and social units and associations. Art helps people to see the relationships, in that viewers can see intersections in contexts other than their own. In this sense, ideology continues to spread or to be reinforced. Ronald Moore writes: The history of Western philosophy is, in fact, replete with testimony on the importance of young people’s exposure to admixtures of artistic, literary, and philosophic ideas in readying them for enlightened adulthood. Just as students must reflect on the fundamental principles of science, politics, history, and so on, if they are fully to understand these disciplines and their role in the life of the state, so they must reflect on the fundamental principles of the arts to understand how these enterprises unite the life of the state with that of the individual (Moore 1994: 8).

Art objects can instill particular religious, political, or moral values. Marcia Muelder Eaton notes: A growing number of theorists, myself included, do not believe that aesthetic experience (and hence aesthetic value) can be neatly packaged and distinguished from other areas of human concern – politics, religion, morality, economics, family, and so on. Art objects do not always, nor even typically, stand alone. Even if some are created to be displayed in museums or concert halls – above and beyond the human fray – many are intended to fill political or religious or moral functions. Their value is diminished, indeed missed, if one ignores this. This is particularly true of the art of cultures other than the one dominant in the West in the first two-thirds of the twentieth century – the art world of wealthy, white, male connoisseurs (Eaton 1994: 25).

The problem with the inscription of ideology in art is that, in conjunction with the traditional perspectives on art interpretation, explorations of alternative perspectives and viewpoints is stilted. The traditional interpretative perspective suggests that there is one accurate interpretation of art, and that the particular interpretation can be taught through the various education venues. Silvers suggests: Effective art, it is thought, should transcend differences of culture and learning – that is, should appeal transculturally or internationally. Thus, art’s power is supposed to derive from how well it accords with human nature in general, not with particular humans and their specialized histories. A corollary encourages us to expect that the capacity to relish are can be activated even at a very early age, as the relevant experiences are essentially human ones and as such are not relativized to socialization or acculturation (Silvers 1994: 53).

As a result, there is only one interpretation of a particular piece of artwork, the cultural context of the piece is not particularly relevant to an understanding of the artwork, and the enduring truths of the artwork can be discovered through critical scrutiny. More importantly, this sort of perspective centers the discovery and dissemination of truth in the hands of “experts” who have the truth about the artwork. Silvers continues, saying: Moreover, autonomy of judgment is reserved for the privileged. For a threshold condition for achieving autonomy is that one enjoy at least minimal recognition as a distinct, and therefore potentially independent, entity. Dependent beings are precisely those who are considered indistinct because inseparable from their attachments and, as such, they do not qualify as autonomous(Silvers 1994: 53).

The museum environment amplifies and intensifies this phenomenon. The museum, in multiple fashions, functions to legitimize and sanction particular artworks and particular interpretations of those artworks. The museum’s architecture and environment often serves to distinguish the viewing of artworks from the “real world” outside the walls of the museum (Walsh-Piper 1994: 106). Museums also make choices about artworks, design factors, and inclusion/exclusion of artworks, which have implications for the viewers. Walsh-Piper notes: Museums make aesthetic choices in everything they do, from the arrangement of spaces, the choice of exhibitions, the arrangement and lighting of the works of art, to the design of furnishings and brochures. The most important choice is the selection of objects to be exhibited. This power to choose is a double-edged sword; choices could be said to entomb values and preserve cultural prejudices rather than to present examples of the best (Walsh-Piper 1994: 107-08).

The role of docents and museum educators cannot be understated. Depending on the instructor’s interpretation of certain works, and the attention that they draw to a particular artwork, the impact of the received interpretation might even be greater.

One way out of this conundrum is to allow students to discover particular messages within their own contexts, and to encourage a more participatory style in art observation and criticism. Instead of instructing students in the appropriate understanding of an artwork, educators might instead simply introduce the student to the piece of art, and allowing the students to discover truths within the artwork for themselves. This sort of perspective allows for art to more fully reach its potential for critical awareness and cultural flexibility. Ronald Moore writes: The rationale for introducing aesthetic subject matter into school curricula is not to be understood as merely the enhancement of art education; rather, it sets the stage for critical reflection, redirected awareness, and heightened appreciation as these pertain to an extraordinarily broad range of objects. Even when aesthetics and philosophy of art are taken as synonyms, it should be understood that the art in question is the art of living no less than it is the art of gallery walls (Moore 1994: 6).

This education serves a valuable function if, and only if, the student is allowed to discover truths from a wide range of perspectives and from a diverse base of cultural premises. Otherwise, art education merely reinscribes another received truth, and the function of education, argumentation, and art criticism is undercut.

One example of this participatory approach is the use of the “imagination stations” at the Dallas Museum of Art in 1997. The next section of this essay describes the make-up of the procedure, as well as engages in a preliminary examination of selected responses to the art in the museum in the sketchbooks.

3. Analysis of Imagination Station Responses

The exhibition Animals in African Art: From the Familiar to the Marvelous centered on the premise that animal imagery in African art can be interpreted as a metaphor for human behavior and that the human experience can be explained through animal imagery. Another concept imbedded in the exhibition is to dispel the myth of Africa as a jungle, complete with jungle or safari animals such as lions, giraffes, elephants, and monkeys. (Roberts 1995: 16) In actuality, these animals are rarely depicted in the artistic traditions of African cultures. The imagery of the exhibition was organized into five main themes: animals associated with the domestic sphere, wild animals of the bush, composite and anomalous animals with supernatural abilities, leopards (the most commonly depicted animal in African art), and the social, political, and metaphorical connections between humans and animals.

The exhibition design differed from many of the Dallas Museum of Art’s other installations in several ways. The foremost obligation for the museum’s exhibition design team was to set up gallery experiences that allowed viewers to take an active role in interpretation and encouraged visitors to write or draw their responses in the exhibition. Elementary school children created a large book of paintings and drawings of animals found in Africa, and that book was placed in a prominent position at the beginning of the exhibition. Monitors showing video footage of animals in natural habitats were interspersed throughout the exhibition. Instead of an information-based, didactic orientation video that so often accompanies exhibitions, a three-minute film of a Malian leopard dance filmed in 1973 played continuously, with only a caption following the video indicating the time and place of the performance. The imagination stations were placed throughout the exhibition near an entrance or exit. These consisted of a podium, sketchbook, colored pencils, and a brief statement to assist viewers in synthesizing the main concept of the area.

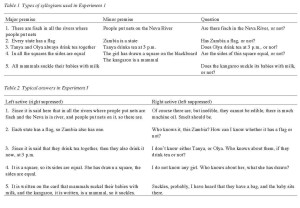

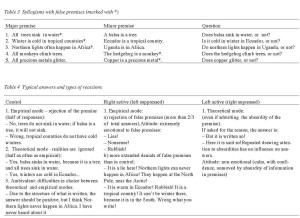

The first imagination station was located at the end of the rooms containing objects depicting animals of the home and garden and the wild animals that exist outside the boundaries of the village. Typical human behaviors are associated with the animals found inside the village. At the various times when acceptable norms of behavior are suspended, and uncivilized actions are sanctioned by the community, the actions do not come from inside the village. Instead, they must be brought in from the bush, where wild or uncivilized animals reside. The guiding statement at the imagination station instructed visitors to think about wild animals they knew and make them into a mask, an instrument, or an ornament. The majority of drawings can be placed into two main categories: animals seen in the wild room transformed into musical instruments, such as flutes or stringed instruments, and domestic animals that have been given the attributes more commonly associated with wild animals. In one example, a pig was given horns and sharp teeth to communicate its wild nature.

In the Composite/Anomalous area, the exhibition focused on the supernatural qualities of certain animals. Anomalous animals, such as crocodiles, have the ability to pass between land and water and are therefore thought to be associated with spiritual forces (Roberts 1995: 138). Artists also constructed art with composite animals dominating the scene, with parts of several animals put together. This artwork is often created to counteract a crisis or mark an occasion of instability in the community. The imagination station asked visitors to create a composite animal that does not exist by combining parts of animals that do exist. Many drawings left by young visitors combined the aspects of animals seen elsewhere in the exhibition such as crocodiles, felines, snakes, and birds, often creating an animal having the ability to fly, swim, and walk, therefore becoming anomalous. Several other drawings included animals not seen in the exhibition (flamingos, bears, and manatee), suggesting those visitors may have been drawing on their own experiences with animals.

It is in the Leopard section of the exhibition that the sketchbook drawings by young visitors are most interesting. The objects in this room included necklaces, claws, masks, costumes, and stools representing leopards in various ways, from recognizable images of crouching and standing animals to jewelry composed of leopard claws. Images of leopards are widespread throughout Africa and are most often associated with military or political power.

The statement at the imagination station encouraged visitors to think of something they use everyday and make it look like a leopard. The responses generally fell into three categories: everyday objects that were included in the leopard area, objects related to the experiences of the visitor, and drawings of actual objects in the exhibition. Several children created drawings of the types of objects in the leopard area, especially jewelry, clothing, and objects used for sitting (chairs, stools, and toilets). These drawings did not recreate the objects, but depicted the idea of the leopard in different ways. The drawings of everyday objects focused on hair and toothbrushes, pencils and pens, eating utensils, computers, cars, and mirrors that included elements of leopards. Different interpretations of leopard toothbrushes included a recognizable brush with only spots added, and a brush with the bristles replaced by sharp fangs and connected to the mouth and head of the leopard with the body curling around to form the handle. Several visitors chose to recreate an image of an object found in the leopard room, namely a cylindrical wooden mask with painted spots and a sack-like leopard costume.

The final gallery of the exhibition focused on objects that combined images of animals and humans. In the catalogue accompanying the exhibition, Roberts notes, “In African cultures, verbal and visual arts reinforce and enrich one another. Proverbs, songs, and spoken narratives, in unison with visual art forms, provide complex multisensory systems of communication. Animals are common subjects of both verbal and visual arts, often portrayed in dynamic interaction as a comment on the nature of social relationships (Roberts 1995: 176). The imagination station invited visitors to think of what kind of animal they would be, and further guided them by asking, “would they be tiny, sneaky, slithery, or carefree?” One young visitor drew a feline body with lion mane surrounding a dog or fox-like face. A brightly colored plume extended from the forehead of the animal and a flag with three horizontal bands of green, yellow, and red was situated atop the animal’s head. Interestingly, the drawings received from this imagination station were most often accompanied by written descriptions. Animals associated with strength (felines and elephants) were common, as were comparisons to snakes and birds. One drawing of a bird in flight was accompanied by the statement, “I’d like to be a bird because I’d like to see things from a birds [sic] eye view.”

The response to the imagination stations was overwhelming and far exceeded the Dallas Museum of Art’s expectations. During the course of the twelve-week exhibition, sixteen sketchbooks were filled with visitor responses. Although directed at young, school-age viewers, visitors of all ages participated in the imagination stations. The museum’s exhibition team, composed of curators, designers, and educators, attempted to create a gallery experience that encouraged visitors to create their own meaning and interpretations of the works of art. At the same time, the team also offered various depictions of animals in African art. The imagination stations and their resulting responses indicate that a need exists for museum visitors to come to terms with works of art from their own perspective.

4. Conclusions and implications

This essay has argued that visual art can function as an argument, and that museums are one site for the study of such arguments. In this essay, we argue that the drawings in the imagination stations are argumentative responses to the artwork in the museum, and that these drawings can be studied from an argumentative perspective as well. This essay only serves as a beginning to the study of these works; there are many hundred pages of drawings left to study.

There are some implications that this study has for the broader study of art as argument, for argumentation and art criticism in general, and for the role of the critic. Initially, it is important to remember the initial conversation that this essay enters into. There are still some questions as to whether or not art can be or should be examined as argument. This essay attempts to provide support for the position that art is one of the more important and powerful venues for argument, and that the study of art can provide some critical insights into the field of argumentation. In particular, we argue that there are benefits to both communities if critics are encouraged to examine visual art from an argumentative perspective. Art can benefit from the advances in argumentation theory over the last thirty years, particularly, the integration of alternative perspectives for the evaluation of arguments, such as the narrative paradigm of Walter Fisher and the insights of critical rhetoricians. Argumentation scholars can not only begin to examine a powerful set of argumentative artifacts, but they can also benefit from the experiences of art critics and art educators/historians.

With regard to argument and art criticism, this essay reinforces the concerns for and the potential of the critical endeavor. Drawing on the works of John Dewey, Joli Jensen argues: We can also rethink our role as artists, intellectuals, social critics. Dewey forces us to find justification for our work that is not smug or self-serving. We must think of reasons why our particular forms of aesthetic practice are any more valuable than those of less status-ridden and privileged groups. . . . Dewey asks us to spend less time exhorting, prophesying and declaiming, and more time watching, listening and responding. He asks us to talk with, not to, other people. He expects us to learn from each other. His metaphor of conversation is a metaphor of exchange – as citizens we are participants in a modern, democratic conversation (Jensen 1995: 375).

The art itself can reveal power relations for what they are to audiences with the potential for action. Art serves a liberatory function when the critic/observer can observe artworks without the constrictions that traditional models of education impose. The imagination stations, in the world of the children, helps to begin this process. Hanno Hardt writes: If for no other reason, the works of Benjamin, Lowenthal and others provide a powerful rationale for the consideration of creative practices in the debate over issues of communication, media and society; their aesthetic or psychological dimensions especially help explain the historical circumstances of social relations. Art discloses the material and ideological foundations of society; it is a manifestation of human creativity and a mode of expression that lends visibility to the inner world. But it also can be the site of critical observation and analysis of the social conditions of society and, ultimately, a powerful means of participating in the emancipatory struggle of the individual (Hardt 1993: 62).

This sort of individualized critique describes what Barbara Biesecker details in her comparison of the works of Michel Foucault and the critical rhetoric of Raymie McKerrow. Biesecker raises the potential that the critical rhetorician, in his or her revelation of power structures and call to change, actually merely reinscribes another hegemonic interpretation. Biesecker writes: “if we take Foucault’s critique of repression seriously and extend its insights to other orders of discourse, we are led to wonder how transgressive, counter-hegemonic or, to borrow McKerrow’s term, critical rhetorics can possibly emerge as anything other than one more instantiation of the status quo in a recoded and thus barely recognizable form” (Biesecker 1992: 353). It is important that critics, either from the field of art or from argumentation, do not succumb to the temptation to merely replace one true interpretation with another. Instead, it is important for critics and educators to allow students to discover relationships in art works, and to make them relevant to their own lives. In this sense, educators can truly create an environment where learning can occur, and make possible the changes needed in Klumpp, Riley, and Hollihan’s post-political age.

Admittedly, the possibility for change is limited, in that there are other constraints on children’s ability to truly open-mindedly criticize art. Children are limited in their range of experiences to bring to bear on the artwork, and they are also limited in the artworks that they are exposed to. There will always be limitations on the range of options, but by allowing children to express themselves and to criticize art in their own way, the liberatory potential is maximized.

Further study is warranted in this area. We hope, in the future, to more thoroughly examine the sketchbooks in an attempt to understand what this work tells us about childrens’ arguments. Also, the cultural impacts of the sketchbooks could be examined, in that they are assessments of African art. Further study could examine how the sketchbook responses function as argumentative responses to the original artworks. This essay, however, has attempted to set the theoretical framework for these future studies by describing the theoretical grounding for the study of art as argument.

REFERENCES

Biesecker, B. (1992). Michel Foucault and the question of rhetoric. Philosophy and Rhetoric, 25, 351-364.

Birdsell, D.S. and L. Groarke (1996). Toward a theory of visual argument. Argumentation and Advocacy, 33, 1-10.

Blair, J.A. (1996). The possibility and actuality of visual arguments. Argumentation and Advocacy, 33, 23-39.

Chase, K. (1990). Argument and beauty: a review and exploration of connections. In: Trapp, R. and J. Schuetz (Eds.), Perspectives on Argumentation: Essays in Honor of Wayne Brockriede (pp. 258-271, Ch. 19), Prospect Heights: Waveland.

Fleming, D. (1996). Can pictures be arguments? Argumentation and Advocacy, 33, 11-22.

Hardt, H. (1993). Authenticity, communication, and critical theory. Critical Studies in Mass Communication, 10, 49-69.

Jensen, J. (1995). Questioning the social powers of art: Toward a pragmatic aesthetics. Critical Studies in Mass Communication, 12, 365-379.

Klumpp, J.F., P. Riley, and T.A. Hollihan (1994). Argument in the post-political age: reconsidering the democratic lifeworld. In: F.H. van Eemeren, R. Grootendorst, J.A. Blair, and C.A. Willard (Eds.), Special Fields and Cases, (pp. 318-328), Amsterdam: Sic Sat.

Moore, R. (1994). Aesthetics for young people: Problems and prospects. The Journal of Aesthetic Education, 28, 5-18.

Pickering, B.A. and R.A. Lake (1994). Refutation in visual argument: An exploration. In: F.H. van Eemeren, R. Grootendorst, J.A. Blair, and C.A. Willard (Eds.), Special Fields and Cases, (pp. 134-143), Amsterdam: Sic Sat.

Roberts, A.F. (1995). Animals in African Art: From the Familiar to the Marvelous. New York: The Museum for African Art.

Shelley, C. (1996). Rhetorical and demonstrative modes of visual argument: Looking at images of human evolution. Argumentation and Advocacy, 33, 53-68.

Silvers, A. (1994). Vincent’s story: The importance of contextualism for art education. The Journal of Aesthetic Education, 28, 47-62.

Walsh-Piper, K. (1994). Museum education and the aesthetic experience. The Journal of Aesthetic Education, 28, 105-115.