IIDE Proceedings 2011 ~ Vol. 2 ~ Down-To-Earth Issues In (Mandatory) Is Use; Part I – Types Of Issue

Abstract

Abstract

The extant discourse about mandatory IS use is not serviceable as a guide to evaluating the quality of such use as experienced by stakeholders. Many ‘down-to-earth’ issues that are crucial to such quality are overlooked. A new approach is required, which is based on what is meaningful in everyday life of use rather than on the abstractions used in academic discourse. Reasons why these abstractions are unhelpful are discussed and Dooyeweerd’s notion of modal aspects is proposed as a foundation for developing more serviceable approaches.

Keywords

Down-To-Earth, Mandatory Use, Dooyeweerd’s aspects

1. Introduction

In the era of technology, many organisations have made substantial investments in information system (IS) with the intention of increasing organisational performance. So the success or quality of IS use is often linked closely to the extent to which it contributes to organisational life, and IS use is one the important areas to be considered by management when implementing or evaluating any IS (DeLone& McLean, 1992; Venkatesh,et al., 2003).

Since the link with organisational performance is complex, broad concepts are often employed in an attempt to understand it. A common example is the extent to which an organisation deploys IT to support operational and strategic tasks (Ives &Jarvenpaa, 1991), and this is the key consequent variable in Davis’ (1989) technology acceptance model (TAM). IS use was among the most frequently used measured of success in 1992 and remained so for at least a decade (DeLone and McLean, 2003). Articles on IS use constitute around one third of the total publication space in the top IS journals, MIS Quarterly and IS Research (Barki, et al., 2007).

There are two problems. Much of this discourse is irrelevant when considering mandatory IS use (MISU) since the use is by definition 100%. So alternative concepts have been suggested, such as ‘intention to use’, which is the secondary output of TAM.Later many studies specifically focused on mandatory IS use (Ram & Jung, 1991; Lou, et al., 1995; Singletary, et al., 2002; Adamson & Shine, 2003; Ward, et al., 2005; Linders, 2006; Hennington, 2007; Lee & Park, 2008).

So why should there be yet another paper on mandatory IS use? The second problem with extant discourse, even on MISU, is that it doesn’t sufficiently express the reality of IS use on the ground.

Despite huge research in IS usage area, the use of the system is still not well understood (Mishra &Agarwal, 2009). Is it only a matter of time and incremental effort before IS use is understood? Yousafzai (2007) has collected 70 constructs related to perceived usefulness in IS use, so is it possible that IS use may be understood by rationalising them? Barki [2008] suggests four approaches to properly understanding the constructs, including defining them clearly, specifying dimensions and relationships, exploring their application to other contexts, and expanding their conceptualizaton.

Whilst such approaches might indeed help towards understanding of IS use, the present situation is reminiscent of some scientific endeavours that Kuhn (1970) observed that had reached a stage ready for paradigm shift. After a long period of incremental correction of previous views, an increasing sense of misfit between experienced reality and theories leads to a new approach to the area of reality, a new paradigm. The primary reason for this paper is to suggest a new way of looking at IS use; this focuses on what might be called down-to-earth (DTE) issues of mandatory IS use. The approach can perhaps be extended to non-mandatory IS use, so “MISU” is often rendered as “(M)ISU”.

In this paper, quality of IS use is conceived more broadly and yet also, paradoxically, in a more precise way, because of a pluralistic approach. In most literature, ‘good’ (or successful, beneficial, high quality) IS use is conceived in terms of the organisation whereas this paper also takes into account the individuals who live and work with, or are affected by, the IS. In most literature, the notion of ‘good’ is located in abstracted, predefined variables like amount of usage, intention to use or perceived usefulness (Davis, 1989), and the plethora of ‘external variables’ encountered in actual experience of IS use [Yousafzai 2007] are deemed meaningful only insofar as they contribute to the predefined variables. This paper reverses this, treating this plethora of ‘external variables’ as that which is truly meaningful, and the supposed abstract variables are defined by reference to, and as an outcome of, what occurs in everyday experience of IS use. In most literature ‘good’ IS use is seen as a goal to which everyday experience should be designed to contribute while in this paper, the ‘good’ is seen as an outcome of that everyday IS use. Most extant research in issues of IS use has been of a positivist nature; this paper takes a more interpretivist approach. Most literature focuses on issues of interest to researchers and the academic or management communities, whereas this paper focuses on issues that are meaningful to users and others who experience the IS in use.

Finally, most literature, including Barki [2008], presuppose that the constructs that are important are those that researchers and others are currently discussing, whereas this paper recognises that there might be many that are not obvious, either hidden behind extant constructs or completely overlooked.

This is one of two papers. This paper introduces the notion of down-to-earth (DTE) issues and provides a philosophical foundation; the companion paper (Ahmad &Basden, 2011) discusses how DTE issues can be researched in practice by discussing an empirical method. The structure of this paper is: First extant issues in (mandatory) IS use are collected together, then a vignette of daily experience of mandatory IS use is reviewed to reveal what down-to-earth issues might be like. The difference between these and extant concepts is discussed, to highlight problems with extant literature. A way of understanding the root of the problem in extant literature is offered by the philosophy of Dooyeweerd, which is introduced. Then the problems of extant approaches are discussed in these terms, to yield proposals for a new approach. This forms the foundation for a second paper, Ahmad &Basden(2011) but also background for Joneidy&Basden(2011), both of which are in the same collection.

2. Survey of literature

In order to evaluate specific cases of (mandatory) IS use as to their quality (and perhaps also to design IS, though this is not the focus here) it is necessary to work with a set of generic factors that are important contributors to high quality (M)ISU. Whether such factors constitute a formal or informal set is not of concern here, but it is necessary to go beyond narrative accounts of instances of use, because we wish to be able to apply the evaluation in other contexts and (re)design the IS innovatively for the future. The set of factors can be applied to a variety of stakeholders, but especially the (potential) primary users of the IS because it is these whose tacit and explicit knowledge of the IS and the tasks they perform is most crucial.

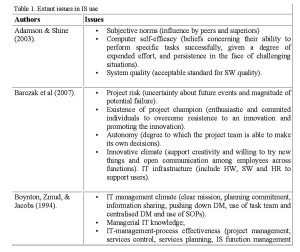

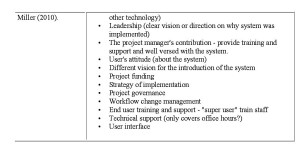

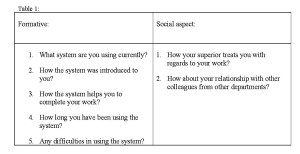

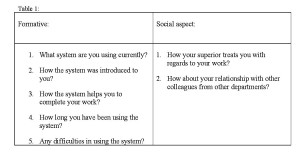

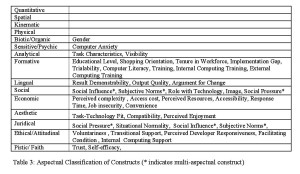

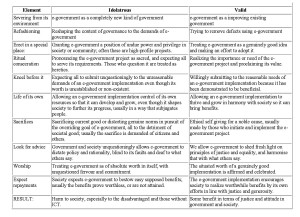

The set of factors should be comprehensive and place no prior restrictions on what it is meaningful to consider, whether these arise from prior prejudices of either the researcher or the researched or taken-for-granted assumptions. The researcher and researched together should be able to reveal anything that might be relevant. A reasonable place to begin is to look to the academic literature to provide factors to consider, because these will be produced by reflection across a variety of situations and will to some extent have been tested for salience (whether by positivist or interpretivist means does not matter here). The current literature relevant to mandatory IS use yields a host of factors, a selection of which is given in Table 1.

This is only a selection of the issues, but in its diversity one can see much confusion, ambiguity and overlap. So, as Barki [2008] points out, there is a need for guidelines regarding how constructs may be developed. Whereas he suggests four approaches (mentioned above) to improving such constructs, we suggest that it might be useful to consider a different approach.

3. Down-to-earth issues in (M)ISU

These issues fulfill the need to build a conceptual theoretical model (formal or informal) of mandatory IS use. While a unified theoretical model can indeed be constructed out of such issues [Venkatesh et al. 2003], it is doubtful how useful such a model would

be in practical evaluation of mandatory IS use. The types of issue found in the literature are not those encountered in everyday life of IS use.

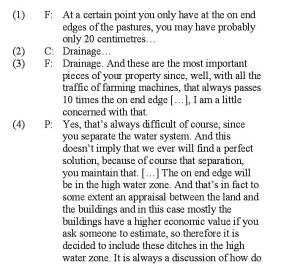

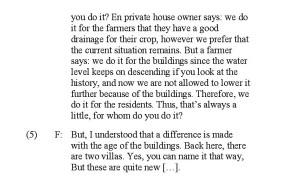

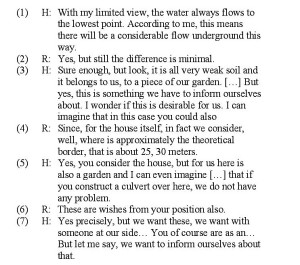

That this might be so is indicated in Etienne Wenger’s vignette of a day in the life of Ariel, a medical insurance claims clerk, found in chapter 2 of Wenger (1998, p.18-34). Her job consisted of taking (paper) claim forms and entering them into the system, but this involved much interpretation and checking prior to the actual entry of data. It was, of course, important to get not only the data right but the information and intention, so that patients and providers (doctors) would receive their due, whether this was what they had claimed for or not. Use of the computer system is, of course, mandatory. Passages are selected below to illustrate DTE issues, and also to indicate how extant constructs cannot always address them adequately. The majority of Wenger’s book concerns his notion of communities of practice and his theoretical understanding thereof. While users of a particular IS might be seen to constitute a community of practice, this is not our main interest here. The vignette is used here, not in relation to CoP, but mainly because it provides a very realistic account compiled from careful, long-term anthropological and ethnographic observations, an account that users of mandatory IS like Ariel would recognise as accurate and appropriate.

3.1 Illustrations of Down-to-earth issues

Wenger’s vignette can be analysed in terms of the issues above, but doing so loses something – something that is important and meaningful to those involved in the IS use described. Here a number of excerpts are analysed in order to illustrate this claim. Each excerpt is given an identification number.

P1. “Ariel is well organized … What she tries to do is process easy claims fast during the morning and early afternoon and so get her ‘production’ out of the way. Once she has reached her daily quota, she uses the last few hours of the day to take care of ‘junk’ claims and to make phone calls … Ariel does this sorting before leaving so that her pile is ready for the next day”. (Page 21)

It is obvious that this organisation of her tasks makes IS use both more tractable for Ariel and more effective for her organisation. How might it be classified under the factors discussed in the extant literature? The nearest in Table 1 is Singletary et al.’s (2002) ‘personal innovativeness’, referring how she organises her day. But what Singletary means comes from Agarwal and Prasad (1998) as “individuals are characterized as ‘innovative’ if they are early to adopt an innovation”, referring to a technological innovation imposed from outside. Such a concept would therefore be of little help in recognising the importance of Ariel’s innovativeness, which is her own. Further, the success of this aspect of her use of the IS is not primarily due to what she did being innovative, but that she is “well organized” in ways that make sense in her situation of mandatory IS use. The following passage illustrates another factor that would be meaningful to users, the quality of information.

P2. “She enters first the type of service, then the name of the service provider, which leads her into the providers file: there she makes sure she checks that the provider’s address is correct since the insured has ‘assigned’ the benefits to be disbursed directly to the doctor. … Since the patient went to such a ‘preferred’ doctor, Ariel must remember to increase the rate of reimbursement from 80% to 85%.” (pages 22-3)

Information quality is mentioned by Linders (2006) and Lin (2010) but, to them, it is determined by accuracy, reliability and completeness. There are three reasons why this is not useful in practical evaluation or design, which are illustrated in the passage. First, these are rather static notions when compared with the “makes sure” and “must remember” in this passage. Second, they are more abstract, requiring further explanation as to what should be done during IS use. Third, some information is more important than others, and what determines whether the information is of low or high quality is not whether it is accurate, reliable and complete as such, but the reason why the information is important. The next passage also concerns information quality, again expressed as normative actions rather than attributes, but it does so in three ways.

P3. “She ignores a number of caution messages and moves to the next screen where she checks the address. It is important to make sure the address is correct so the check will reach its destination properly. You definitely will get a void if the address is wrong [which means she would have to enter the claim again].” (page 22)

One is that there are caution messages that are meaningless. The second is that she must act to ensure quality of the address, and the reason is given here. The third is that the system (whether human or technological is not made clear) is designed to prevent bad addresses getting through, which shows that quality of address is serious. This shows the diversity of types of information quality, which the collective term ‘information quality’ would not disclose. Duplicate information is also a matter of information quality, and Ariel checks this.

P4. “Now that claim looks like a duplicate, but Ariel can’t tell from the claim history on-line; she needs to check the original bill to see if the services covered are really the same.” (page 31)

The following three passages are about (perceived or actual) ease of use, whichis as diverse as information quality. The first ease of use arises because the data is readily available on the forms and seldom gives any surprises, so certain input actions become habitual.

P5. “The rest of the claim goes fairly fast: enter the code for the diagnosis, for the contract type, skip the coordination section, indicate the assignment of benefits.” (page 23)

The second refers to being able to judge beforehand what one needs to do.

P6. “… Of course, you never really know just by looking at the claim how involved it is going to be, because there can be surprises when you open the customer’s file on the system. But with some experience, you have a pretty good idea at first sight about how difficult a claim is likely to be”. (page 21)

The third is whether the way the system is designed makes it easy to forget the correct date, which reduces ease of use.

P7. “… she has to enter the year the claim is for and the date the claim was received, which was stamped in red by the clerical employee who opened the mail. It is easy to forget to do that because the system enters by default the date of the last claim processed” (page 22)

Here is an extreme example of (not) ease of use:

P8. “Now Ariel realizes that she will need to access information to answer this person’s question and that she will not be able to finish the claim she is currently processing before having to do so. She will have to `clear’ out of this claim and thus lose all the information she has already entered. This stupid system, you have to lose all your work every time you are interrupted and that’s pretty often.” (page 24)

There are many other types of ease of use, which is too general a factor to apply directly in evaluating or designing IS use. Davis (1989) recognises this in that he assumes those who employ TAM will nominate their own set of ‘external variables’ that feed into perceived ease of use. Yousafzai et al. (2007) have collected together 70 such variables but examination shows that these still are subject to the types of criticism we are making here. Green &Petre’s Cognitive Dimensions framework [1996] might offer external variables for ease of use, but they do not extend to the other factors listed above, and below we propose an approach that covers all issues.

P8 (having to lose data) might come under what Adamson & Shine (2003, p.444) call system quality; obviously a system that can access only one record at a time in such usage situations is of poor quality. But ‘system quality’ as conceived by Adamson & Shine (2003, p.444) would not pick this up, because it is concerned with “software bugs and errors, hardware or facility failures … poor input data quality.” The system “must be acceptably secure, accurate and reliable”. Often, as here, systems can be used in ways the designers did not anticipate, so there needs to be a certain generosity in design.

In several passages above, ease of use arises from what Singletary et al. [2002] call prior computer experience. Again, we find an issue that is not very informative because it covers too many different things including, as illustrated here, prior experience of judging overall difficulty and that certain portions of data are easy. The following passage shows a different type of prior computer experience: being able to detect the errors or the unusual features that demand special attention, distinguishing them from ordinary information.

P9. “Ariel types and writes impressively fast. Her eyes scan computer screens quickly, knowing what to look for. Check everything on this last screen and press enter.” (page 30)

The following is about prior experience, not the computer as such, but about the task, which is creating a story from the data, and not about what is correct but about what is reasonable.

P10. “You have to develop a good sense of how much is reasonable, juggling the whole thing to produce quickly a reasonable story. What makes a story ‘reasonable’ can’t be taught during the training class. Even her instructors acknowledged that trainees had to learn it “the right way” for now but that, once they got to the floor, they would learn the shortcuts.” (page 31)

The following short sentence exhibits four issues.

P11. “On the computer, she flips through the claim history to get an idea of how this has been handled so far.” (page 27)

Three are found in the earlier list: information quality (Ariel acts to enhance quality of her interpretation), perceived ease of use (she can ‘flip through’), perceived usefulness (the claim history is useful for her to understand). But none of these really express what is important in this use, even when taken together. What really makes her activity ‘successful’ is a factor not mentioned above: she goes beyond what is strictly necessary (the extra work of getting to know the claim history) and it results in better interpretations. Using the factors in Table 1, would both unnecessarily complicate analysis of this short statement and also miss the essential one.

Several examples of what Ram & Jung [1991] call help-seeking behaviour may be found in Wenger’s vignette. The first is quite straightforward, about what information to enter, and is what Ram & Jung had in mind.

P12. “On an ambulance claim, Ariel does not see a diagnosis. She goes over to Nancy, who tells her to find one that would do in the patient’s claim history” (page 30)

In the following, Ariel seeks help, not primarily to know what information to enter, but to obtain advice on what is appropriate and to support her own judgement.

P13. “Then she takes a look at the second void. What? But the patient was seen for headaches. And neurological exams for headaches are considered medical even if there is a secondary psychological diagnosis. Therefore the ‘psych’ maximum [presumably lower than the maximum for ‘medical’] does not apply. She had actually discussed this case with Nancy and Sheila. She even talked with Maureen, the back-up trainer, who helps people with difficult cases and had agreed with her conclusion.” (page 20-21)

The following could be seen as help-seeking behaviour, but it is not about information or how to use the system. It is about seeking to reduce one’s workload (justifiably so in this case).

P14. “It is ten to four; Ariel will be leaving in 20 minutes. She decides to stop dealing with her junk and to prepare her work for tomorrow. She goes to Sara, the assistant supervisor, to ask her for some work. When claims arrive at Alinsu, they are opened by the clerical unit and sorted by plans … Ariel pleads for an easy pile, reminding Sara of the difficult work she did in the beginning of the week. Sara gives her a pile from the City Hall … Ariel thanks her: tomorrow she will be able to make production early and then catch up on her junk.” (page 33)

While ‘help seeking behaviour’ might adequately express what is meaningful to an observing researcher, it does not do justice to the diversity of reasons why help is sought. What is important in mandatory IS use is not the behaviour of seeking help, but that help is received from others and what kinds of help are received. Sometimes, help is received without being sought, as in the following:

P15. “Next, she selects the customer’s son as the patient from a list of dependents. She is careful because it is easy to choose the wrong dependent; she got voided for this last month. She makes sure the son is under the age of 19. He is not, but there is a recent note from Patty on his file that he is a full-time student. Patty must have investigated it. She is reliable.” (page 22)

This would probably be missed by ‘help-seeking behaviour’. What is important about the help received is that Ariel does not have to do this work because Patty has done it for her, and that Patty is known to be reliable and what she does can be trusted. Here is another example of help received, which would also be missed because it is accidental and informal:

P16. “… Annette replies, “I think it’s ‘end of the month’.” But Joan corrects her, “No, they just changed it. It was in a memo last week.” Ariel overhears the conversation and makes a mental note.” (page 31)

Such learning occurs more in those who have an attitude of wanting to do their best in the work, than in those who couldn’t care less. A careless attitude causes trouble for others, as in the following passage:

P17. “In this case, she pays the claim and enters a claim note stating how much has been paid out of the limit so far. In this office, some people are good about notes and some are not. For instance, every time you change an address – something Ariel has already done three times today – you are supposed to enter a note to that effect, with the date and the source of the new address, so that another processor will not put the old address back in. Because not everybody does it, it causes trouble for other people.” (page 28)

It might be classified under what Ram & Jung (1991) call complaint behaviour, but that is not entirely appropriate. So might the fact that Ariel exclaimed “What! But …” in passage P13. But speaking about behaviour does not reveal what is important in both these cases, namely the feeling that what others do is unfair or ungenerous. It seems to be an issue that has been overlooked by the literature so far.

This may be classified under complaint behaviour (Ram & Jung 1991). Its importance to mandatory use is not the complaint itself so much as the reason for the complaint. In this case it is that Ariel might feel inconvenienced unfairly or even victimised. So the user turns against the system (combination of technical and human).

P18. “When they hit the key that indicates they are done, the computer system gives them a batch number. If the number ends with a D, no problem, it will just get paid and archived. If the number ends with a Q, the claim must be sent to quality review [which might reject it, and is seen as a black mark against one’s work] … She does not know exactly to what degree the appearance of a Q is determined by the type of claim being processed or by the way that she is processing it, but she heard that her supervisor can manipulate the system to send specific claims to quality review. Ariel has been getting a greater number of Qs than usual. As she gets this one, she complains aloud: “What? Another Q? That’s terrible!.” (page 30-33)

Help received can build up what Ram & Jung (1991) call skill in use, but there are other ways to this, such as learning shortcuts:

P19. “… got to keep processing moving, keep the cost per claim down, but this is the kind of shortcut you never get in training. Without them, there is no way the job could be done … In training, everything looks so strict and black-and-white. But on the floor, everybody learns the shortcut in order to meet production. For instance, in training, you are taught to start a claim by filling out the forms that will serve as cover sheets for microfilmed records. Yet much of the information on the cover sheets is never used and is redundant with the attached claim record. So experienced processors do not fill out the form completely; they wait until they have completed the entire claim”. (page 30)

Finally, the following passage concerns not the mandatory use of the IS as such but about the atmosphere of working.

P20. “There is a problem with the toll-free 800 number … Management has a suspicion that this number was given out by some processors to their acquaintances as a way of calling them free of charge. From now on, all phone calls exceeding fifteen minutes will be marked. Harriet senses the tension that her remark has brought into the meeting and is quick to clarify that the marking of these phone calls does not in itself constitute an accusation. … Still the subject seems delicate, and there is some grumbling and a few defensive remarks.” (page 25)

Such factors have an indirect impact on mandatory use, many positive but some negative. It is not clear however how they might be included in the factors listed in Table 1, nor even whether they should be. The mention of ‘grumbling’ suggests ‘complaint behaviour’ but this is minor and in no way expresses the main problem, which is located in attitudes of advantage-taking by “some processors” and attitude of suspicion Management.

3.2 The nature of the problem

It should be clear that there is a great difference between the issues illustrated in Wenger’s text, and the constructs in Table 1, discussed in the IS usage literature. Wenger’s issues seem more ‘down-to-earth’, and we can see immediately and intuitively how they might affect the quality of experience of (M)ISU, at both individual and organisational levels. By contrast, with many extant issues in Table 1 it is less immediately obvious how they might affect the quality of (M)ISU. Why is this? A number of reasons can be adduced.

One problem is that some of the issues are at an unhelpful level. These factors relate either to the development of the IS before use, such as ‘project risk’, or to the senior management’s view of the IS, such as ‘Existence of project champion’, ‘IT-management-process effectiveness’ and ‘results demonstrability’. Frequently the word ‘innovative’ indicates an unhelpful level; that something is innovative might be of interest to senior management who wish to enhance their own reputation, but is of little concern to the users (except when it makes work harder for them!). The kind of innovativeness that Ariel displayed in P1, which is relevant to users, is not within Singletary et al.’s [2002] use of the term and would not be of interest to senior management.

That `innovativeness` is meaningful at both levels – albeit in different ways – suggests that issues at an unhelpful level can be ‘translated’ into a form that is relevant to (M)ISU. Another example is the concept of project champion, who is “enthusiastic and commited individuals to overcome resistence to an innovation and promoting the innovation” might be translated to be someone who is enthusiastic and committed to the use of the system, inspiring others to see that what they are doing is worthwhile and important. If such translations are to be made, a basis on which to make the translation is needed.

‘Project risk’ is also at the wrong level, being of interest to senior management and IT implementors rather than users. It could be translated to the user context, by removing the word ‘project’, but this is still unhelpful for a different reason, discussed below.

A second problem is that some factors contain unhelpful connotations. Cultural connotations and assumptions within which the researchers or analysts operate, cause the analyst to focus on certain aspects of the situation and overlook others. In IS research the connotations are often technological and organisational. For example, in the literature, ‘help-seeking behaviour’ is assumed to refer to help with mastering the technology, because IS research is permeated with a central interest in technology in use. By contrast, in the Wenger vignette, help was sought for many other things that are still related to use of the IS, such as:

* to complete a form (P12)

* for vindication and ensuring the appropriate decision (P13)

* to reduce work load (P14)

* to keep to the rules (P16).

What was important to the quality of (M)ISU is not the activity of help-seeking itself but the reason why help is sought. Moreover, it matters little whether the help is sought or whether it is received in other ways, such as by being overheard (as in P16), in which case alertness and willingness to learn are important issues. To focus on ‘help-seeking behavior’ might be of interest to psychology researchers but is not, as such, so meaningful to users. The problem here lies in the unspoken technological and organisational connotations attached to concepts within the IS research community, because these restrict what is assumed to be meaningful in a way that does not necessarily reflect the researched situation. A way needs to be found to break open such connotations and assumptions.

A third problem is that of unhelpful abstraction. Some issues in Table 1 express something so general that the analyst cannot employ them in evaluation or design, without prior work to imagine the kinds of thing involved. Risk is an example of such an abstraction; risk means “the possibility of loss, injury, disadvantage or destruction” [Webster, 1975]. Since almost any type of thing can go wrong, the analyst would have to know the entire range of things that can go wrong before ‘risk’ is a helpful issue. It is seldom that such a condition is met, even when restricted to a particular context. All analysis involves abstraction of some degree; helpful abstraction is that which helps in sharply highlighting issues that are important to (M)ISU while unhelpful abstraction remains too general and depends on the analyst instantiating the generic issues from either an external list or their own experience before they can be useful. A way needs to be found to abstract from idiographic narratives to something precise in meaning. In P15 above we see Ariel trying to minimise risk (as researchers would put it) but it is very specific risk: of being voided. To Ariel, it is not risk as such that is important, but being voided.

The fourth problem is unhelpful combination. Some constructs express multiple types of issue. For example, computer self-efficacy expresses the ability to perform tasks successfully despite challenges. Not only is this not an easy term to explain, but it depends on several kinds of thing, illustrated by P4:

* the kind of challenge (possibility of duplicate claim);

* how important the task is (ensure appropriate payment, and prevent double payments);

* the process of surmounting the challenge (search for the original claim);

* willingness to make the extra effort to do this.

If these are fully specified, the difficulty for the analyst, during evaluation, is simply to remember and properly understand them all. The difficulty is increased enormously when, as is usual, the components of the combination are unspecified. A way needs to be found to separate out the issues that are meaningful in distinct ways, but without becoming overloaded with detail.

Finally, there are important issues that are missing from the literature, at least up to the present time. In Wenger’s vignette, P20 expresses attitudes of advantage-taking and suspicion, which affect the ISU. Attitude in particular is difficult to observe and measure (positivist research) or interpret (interpretivist research), and perhaps for that reason is seldom discussed in academic literature on (M)ISU. The literature will always miss things; for example, until Davis published his groundbreaking (1989) thesis on TAM, the human factors community focused on ease of use and ignored usefulness. A reliable way is needed to discover and think about issues that are often overlooked during practical evaluation.

3.4 Towards a new approach

At the root of all the problems described above is meaningfulness. DTE issues are those that are meaningful to users and the situation of use, including all its stakeholders. Each of the above problems may be seen in terms of meaning:

* Unhelpful level: Some extant issues are meaningful to the wrong people or roles, and not to users.

* Unhelpful connotation: Some extant issues are narrowed to their technological (or other cultural) meanings.

* Unhelpful abstraction: Some issues are too broad in their meaning.

* Unhelpful combination: Some issues combine multiple meaning that should be separated out conceptually.

* Missing: Some of what is meaningful in the situation of ISU is overlooked.

However, the problem that immediately faces us is the diversity of DTE issues, which seems limitless. Is it not unreasonable to expect researchers or analysts to think of them all? Many DTE issues depend on the specific situation and its specific context, the combination of which is unique. To approach DTE issues idiographically, as a plethora of individual instances would be too unwieldy and yet still omit many issues that are not meaningful to us. There needs to be some generality in the approach. But on what may generality be based?

There is a different approach to generality, which might provide a way forward: one that directly focuses on meaningfulness. The groundwork for this approach was laid out inthe philosophical investigations of the late Herman Dooyeweerd (1894-1977).

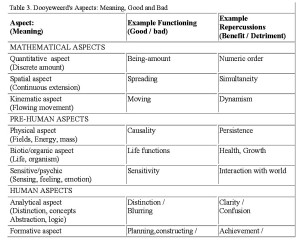

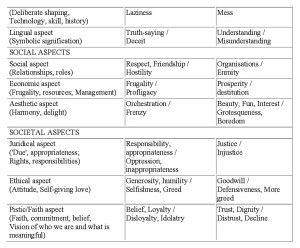

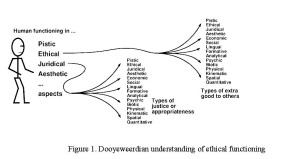

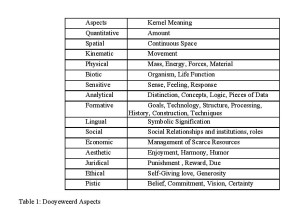

4. The contribution of Dooyeweerd’s notion of aspects

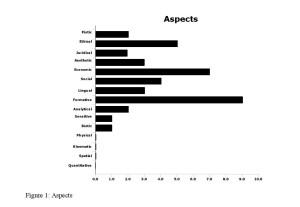

Basden (2008a) has suggested that IS use may be understood by reference to a suite of fifteen aspects initially proposed by Dooyeweerd [1984/1955], and suggested that, in principle, this suite of aspects should be able to cover all that is meaningful in IS use. It is proposed here that a Dooyeweerdian approach can both explain most of the ways in which the extant factors are unhelpful, and provide a way to reveal, study and discuss DTE issues such as are portrayed in Wenger’s vignette.

Grounded in a presupposition of creation, fall and redemption [Dooyeweerd 1979] Dooyeweerd held that all that occurs in the world, whether human, social or ‘natural’, is constituted in responses to diverse kinds of law (such as physical law, which is more determinative, and lingual, social and juridical law, which are non-determinative), that each different kind of (non-determinative) law defines a different kind of ‘good’ (or success or benefit; for example communicational good differs in kind from justice or generosity), that this law that has the character of promise (“If you do X then Y is likely to result”), that outcomes of what occurs are the combination of the results (Ys) of different kinds. Each kind of law (‘law-sphere’) is expressed in temporal reality as different aspects thereof. The desirability of outcomes is defined by reference to the innate norms of law-spheres, but achieving a given outcome involves human functioning across their whole range, and cannot be predicted nor fully controlled. However, Dooyeweerd held that when we function well in all aspects then the outcomes are likely to be healthy and beneficial in many ways, and this provides an approach on how to understand the implications of IS use. Moreover, each different basic kind of law is a kernel that also determines a distinct way of being meaningful.

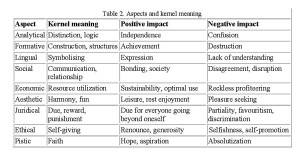

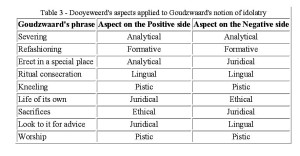

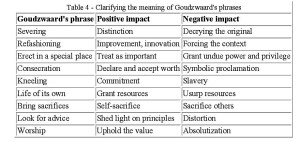

Dooyeweerd delineated fifteen distinct aspects, or law-spheres, summarised in Table 3. It can be seen that they cover both natural,

human-cognitive, social and societal issues. This offers a way to link individual, DTE experience of IS users with organisational outcomes.

This provides a way of seeing the ‘down-to-earth’ issues, those issues that are meaningful to IS users and others, as diverse and meaningful and yet also constitutive of resultant quality of (M)ISU. Analysis involves separating out these aspects of any situation (e.g. of (M)ISU), both of the way in which users function and of the resultant outcomes.

The reader might justifiably ask why it is appropriate to consider Dooyeweerd. There are a number of reasons. The most important practical reason is the wider coverage of Dooyeweerd’s aspects. Many suites of aspects have been proposed, though under diverse terminology, including Hartmann’s [1951] strata, Bunge’s [1979] systems levels, Habermas’ [1986] action types, Maslow’s [1943] needs. All these may be seen as specialised subset’s of Dooyeweerd’s aspects. This means thatDooyeweerd’s suite is the most comprehensive.

In addition, Dooyeweerd’s notion of aspects is richer, in that to him aspects are not merely categories or strata, not merely types of thing or system, not merely types of action, not merely types of need. They are spheres of meaning and law, from which these may be derived. Being spheres of meaning, they provide a set of ways in which things may be meaningful, and hence a multi-aspectual ‘lens’ with which to view situations. Being spheres of law, they have an important normative component, enabling the analyst who employs them to address issues of good and bad, in addition to types of thing or activity. Dooyeweerd’s suite is directed towards everyday human experience rather than being an ontological theory. It is the outcome of a lifelong reflection not only on his own experience, but also on what thinkers have written over the past 3000 years. Finally, Dooyeweerd proposed philosophical tests for candidate aspects, especially the method of antinomy. Despite this, he was always cautious about claiming any ‘truth’ for his suite, recognising that every suite must be open to amendment.

This is perhaps why Dooyeweerd’s aspects have proven useful in many areas (for example, de Raadt 1989; Bergvall-Kåreborn&Grahn 1996; Winfield, Basden&Cresswell 1996; Eriksson 2001; Bergvall-Kåreborn 2001; Basden 2002a; Mirijamdotter&Bergvall-Kåreborn 2006; Basden& Wood-Harper 2006; Basden 2008a, Basden& Klein 2008; Basden 2010). They were designed primarily with the everyday, pre-theoretical attitude and experience in mind, but can be used as tools for theoretical analysis since theoretical analysis itself is part of the everyday reality that is governed by the aspects. They are aspects of everyday life, and this makes them admirably suited to understanding down-to-earth issues of IS use.

5. A Dooyeweerdian account of unhelpfulness

Here we explore how Dooyeweerd might account for the problems discussed above, and offer ways of overcoming them.

That some issues are at an unhelpful level, focusing on what is meaningful to parties other than those involved in the day-to-day use of the IS, may be accounted for by Dooyeweerd’s recognition that all human beings function in the pistic aspect and hence will commit themselves to some origin of meaning. Origin of meaning can either be the entire range of aspectual meaning, as in everyday life, or can be narrowed down to a few or, in the case of reductionistic tendencies, to just one aspect. In many cases, the origin of meaning is determined by our role; for example senior management tends to focus on economic aspect (profits) and pistic aspect (reputation) and ISD project managers focus on formative aspect (technology) and economic aspect (budgets, deadlines). By contrast, in everyday life all aspects are important in principle. Even if individual users focus on certain aspects, the wide variety of users will ensure that most aspects are active. So the analyst needs to be aware of all the aspects at once, and not only those that happen to be important to their own research or to managers or IS developers.

Translation from the unhelpful, role-dominated level, to the everyday life of users can be assisted by Dooyeweerd’s aspects because, Dooyeweerd claimed, all human functioning occurs in response to a single common suite of aspects – the researcher, the manager, the IS developer, the user and all others. Translation may be effected by identifying which aspect mainly makes the unhelpful level issue meaningful, and then asking in what ways that same aspect might be meaningful in the user situation. For example, project champion is mainly of the pistic aspect (vision, commitment). The earlier suggestion of translating to a person who believes in the ISU and encourages others to do so, arose from asking how the pistic aspect might be important in maintaining high quality (M)ISU.

That issues might contain unhelpful connotations can likewise be accounted for by reference to certain meaning-spheres (aspects) being elevated and others overlooked. For example, the target of help-seeking behaviour can be issues that are meaningful in any sphere. But IS researchers, by being more acutely aware of the importance of technology (formative aspect) tend to more readily interpret this as help with technology. In Wenger’s vignette help is sought or otherwise received for things that are meaningful in other spheres, such as:

* completion of form (P12): lingual

* vindication and ensuring the appropriate decision (P13): pistic with juridical

* reducingworkload (P14): economic

* to keep to the rules (P16): juridical.

That one can expect a variety of aspects in the situation of (M)ISU comes from Dooyeweerd’s aspects being all present in the pre-theoretical engagement with the world, which is characteristic of (M)ISU.

Such targets of help, of or any other human behaviour, can be differentiated fairly easily by the aspects, without this becoming too onerous. The cultural connotations embedded in an extant concept can be made less problematic by first identifying which aspects they emphasise and then retargeting the concept towards the other aspects.

That some issues are unhelpfully abstract is accounted for, not by reference to abstraction as such, but to abstraction of multi-aspectual phenomena. (Abstraction is recognised by Dooyeweerd as central to research, and he discussed the conditions under which it is possible and valid [Basden 2011].) Under Dooyeweerd’s approach, most phenomena are qualified by a single aspect (for example, justice is juridical) but there are a few that cross all aspects (functioning, possibility, good, bad, knowing, being). Risk is one of these in that “the possibility of loss, injury, disadvantage or destruction” [Webster, 1975] includes not just one but two multi-aspectual concepts: possibility and bad. However, in P15, risk of being voided is very specific: voiding means a black mark against one (pistic aspect) and a lot of extra work (economic aspect). It is not risk as such, but the pistic and economic aspects that are of most importance to Ariel in her MISU. So, in abstracting from the idiographic narrative or situation, the analyst should not be content with abstraction as such but should always ask themselves whether the concepts or constructs that have been abstracted are sharply meaningful in one or perhaps two readily identifiable aspects, which have meaning to those being researched.

That some issues are unhelpful combinations may be accounted for by Dooyeweerd’s understanding of human activity as always involving all aspects. So when the analyst tries to fully analyse human activities they are likely to find a confusing host of aspects. Thus for example ‘computer self-efficacy’, as the ability to perform tasks successfully despite challenges, involves not only the following aspects:

* kind of challenge: analytic aspect;

* how important the task is: juridical aspect;

* the process of surmounting the challenge: formative aspect;

* willingness to make the extra effort to do this: ethical aspect

but more besides, such as self-confidence (pistic aspect), the excitement of some challenges (aesthetic aspect) and their nuisance value (economic aspect).

When faced with unhelpful combinations, it is useful for the analyst to separate out the distinct aspects of that activity, by asking what is meaningful to those being researched. One way to do this is to ask the researched about each aspect in turn, but that proves to be rather stilted and, though better than some extant approaches, fails to elicit the tacit knowledge that is important to the success of the work activity and is the taken-for-granted knowledge of the community of practice [Wenger]. Instead, it is preferable to approach the researched with questions and encouragement that help them to open up and express all that is meaningful to them, while the analyst has, at the back of her/his mind, an awareness of aspects, and then analyse what is said by reference to aspects. This approach is the main topic of Ahmad &Basden [2011].

That some issues are missing from consideration in the literature may be accounted for by saying that the research community has not yet found the aspect important. Dooyeweerd’s suite of aspects aspires to complete coverage of all possible distinct kinds of meaning and, though Dooyeweerd himself held that no suite “may lay claim to material completion” [Dooyeweerd 1955,II:556], nevertheless it seems more complete than most competing suites. So Dooyeweerd’s suite may be employed in checklist mode, to identify those spheres of meaning that are emphasised in the literature and those which are ignored. This is better carried out informally, with the researcher being always alert to which aspects are being given more emphasis and which, less. For example, the importance of attitudinal and pistic aspects, expressed in attitudes and deep beliefs makes the researcher more aware of attitudes of the management in Wenger’s vignette.

6. Discussion and conclusion

This paper suggests a new approach to studying (mandatory) IS use, using Dooyeweerd’s aspects (spheres of meaning) to reveal and understand down-to-earth (DTE) issues, which determine the quality of (mandatory) IS use. What is down-to-earth cannot be precisely defined because down-to-earth implies highly diverse and intuitive. Instead, it has been illustrated by a vignette from Wenger’s [1998] discussion of communities of practice. Barki [2008] suggests that constructs should be seen, not primarily as predefined attributes of a situation, but as arising from and constituted in actual human behaviours in the situation. A number of differences have been identified between the DTE issues illustrated there, and the extant issues. While a few of the extant constructs might be DTE, most of them tend to be unhelpful in their level, connotations, abstractions or combinations and even so important issues are overlooked.

The proposal here is to employ Dooyeweerd’s aspects as a lens with which view (M)ISU. While use of conceptual lenses is common in interpretivist IS research, those lenses are often theoretical and uni-aspectual (for example, when Adam et al. [2006] explicitly uses gender and technology theory as a lens) and often result in narrowed views. By contrast the lens offered by Dooyeweerd’s aspects is diverse and oriented to everyday intuition, and thus uniquely suited to DTE issues. By means of this it enables the analyst to be open to a wider range of down-to-earth issues than do theoretical approaches. As suggested above, the various types of unhelpfulness discussed above may be avoided in the following ways, by analysing which aspects make concepts meaningful and, where necessary, taking the following actions.

* To avoid unhelpful level, the analyst should check to what extent concepts that emerge are meaningful mainly to themselves, managers or IS developers rather than users. If so, these might be translated by identifying which aspect makes them meaningful, and then asking in what ways that same aspect might be meaningful in the user situation.

* Unhelpful connotations can be avoided if the analyst recognises which aspects their own community tends to emphasise and then retargeting concepts they identify towards the other aspects.

* To avoid unhelpful abstraction, the analyst should ensure that concepts that have been abstracted are sharply meaningful in one or perhaps two readily identifiable aspects, to those being researched, rather than being general.

* Unhelpful combinations can be avoided if the analyst looks, not for things (events or behaviours or structures) but for the way such things are meaningful and normative to those being researched.

* Missing issues may be highlighted by employing Dooyeweerd’s suite of aspects in checklist mode, to identify those spheres of meaning that tend to be ignored.

These principles may be applied to extant constructs, and Joneidy & Basden (2011) in this volume shows some of them in action. They might be more effective however if applied directly to qualitative analysis of the usage situation, as explored by Ahmad & Basden (2011). That approach does not begin with extant concepts, but suggests uncovering what is meaningful to users in their everyday IS use by reference to Dooyeweerd’s aspects.

The argument in this paper has, of necessity, been indicative rather than exhaustive. Therefore, more discussion of this kind is needed, as critique and possibly to refine the approach. Nevertheless, it opens up a new approach. Dooyeweerd provides a philosophical underpinning for not only understanding the nature of DTE issues, nor just showing their diversity, but also for explaining why the notion of DTE issues is needed for analysis and understanding of IS use.

This paper has not, however, provided empirical evidence of the validity of this approach. Some initial evidence is provided by two other papers in this collection. Joneidy&Basden [2011] employ Dooyeweerd’s aspects to examine extant constructs identified in IS research and collected by Yousafzai [2007]. That approach presupposes the extant concepts and provides incremental improvement on the current scientific position. Ahmad &Basden [2011] introduce a new way of approaching (M)ISU, a new paradigm. Instead of taking existing constructs, they use Dooyeweerd’s aspects to investigate directly the situations of (M)ISU to get behind what is expressed and to reveal hidden issues.

Though this paper has restricted itself to MISU in organisations, the aspectual approach might be extended. First, there is nothing in the approach that presupposes ISU is mandatory; so it might be extendible to understanding issues of voluntary IS use. Second, there is nothing that presupposes the users are in an organisational setting; so it might be extendible to non-organisational use, both individual use at home and global use. This suggests this Dooyeweerdian approach might be useful in understanding the less traditional versions of IS use, such as social networking, blogging, wiki’ing and game-playing. Such use is likely to be even more characterized by down-to-earth issues than is mandatory organisational IS use.

About the authors:

i. Andrew Basden – Salford Business School, University of Salford, Salford, UK – A.Basden@salford.ac.uk

ii. Hawa Ahmad – (h.ahmad@edu.salford.ac.uk / hawahmad@iium.edu.my) School of Business, University of Salford, United Kingdom; Kuliyyah Economics and Management Sciences, International Islamic University Malaysia

REFERENCES

Adam A, Griffiths M, Keogh C, Moore K, Richardson H, Tattersall A. [2006]. Being an ‘it’ in IT: gendered identities in IT work. European Journal of Information Systems, 15:357-78.

Adamson, I., & Shine, J. (2003). Extending the New Technology Acceptance Model to Measure the End User Informations Systems Satisfaction in a Mandatory Environment: A Bank’s Treasury. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 15(4), 441-455.

Agarwal, R., & Prasad, J. (1998). A Conceptual and Operational Definition of Personal Innovativeness in the Domain of Information Technology. *Information Systems Research, 9*(2), 204-215.

Ahmad, H., &Basden, A. (2011). Down-to-earth issues in (Mandatory) Information System Use; Part II – Approach to Understand and Reveal Hidden Issues. – details to be supplied by IIDE/CPTS editor.

Barczak, G., Sultan, F. and Hultink, J. (2007), ‘Determinants of IT Usage and New Product Performance’, Journal of Product Innovation Management, 24 (6), 600-613.

Barki, H., Titah, R., &Boffo, C. (2007). Information System Use-Related Activity: An Expanded Behavioral Conceptualization of Individual-Level Information System Use. Information Systems Research, 18(2), 173-192.

Barki, H. (2008). Thar’s gold in them thar constructs. The DATA BASE for Advances in Information Systems, 39 (3), 9-20.

Basden A. (2002a) “A philosophical underpinning for I.S. Development” pp. 68-78 in Wrycza S (ed.) Proceedings of the Xth European Conference on Information Systems, ECIS2002: Information Systems and the Future of the Digital Economy. University of Gdansk, Poland, 5-10 June 2002.

Basden A. (2002b). The Critical Theory of Herman Dooyeweerd ? Journal of Information Technology, 17, 257-269.

Basden A. (2008a). Philosophical Frameworks for Understanding Information Systems. IGI Global Hershey, PA, USA.

Basden A. (2008b) Engaging with and enriching humanist thought: the case of information systems. PhilosophiaReformata, 73(2), 132-53.

Basden A. (2010) How Dooyeweerd Can Engage With Extant Thought: Expanding Kleinian Principles in Information Systems Use Today. In: Goede R, Grobler L, Haftor DE (eds.) Interdisciplinary Research for Practices of Social Change. Proc. 16th Annual Working Conference of the Centre for Philosophy, Technology and Social Systems (CPTS), 13-16 April 2010, Maarssen, Netherlands.CPTS, Maarssen; BZ Repro, Haaksbergen, Netherlands. ISBN/EAN: 978-90-807718-8-8

Basden, A. (2011) Enabling a Kleinian integration of interpretivist and critical-social IS research: The contribution of Dooyeweerd’s philosophy. European Journal of Information Systems. 20, 477-489.

Basden A., Klein HK. (2008) New Research Directions for Data and Knowledge Engineering: A Philosophy of Language Approach. Data & Knowledge Engineering, 67 (2008), 260-285.

Basden A., Wood-Harper AT. (2006) A philosophical discussion of the Root Definition in Soft Systems Thinking: An enrichment of CATWOE. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 23, 61-87.

Bergvall-Kåreborn B. (2001) Enriching the Model Building Phase of Soft Systems Methodology. Systems Research and Behavioral Science 19, 27-48.

Bergvall-Kåreborn B., GRAHN A. (1996). Expanding the Framework for Monitor and Control in Soft Systems Methodology. Systems Practice 9, 469-495.

Boynton, A. C., Zmud, R. W., & Jacobs, G. C. (1994). The Influence of IT Management Practice on IT Use in Large Organizations. MIS Quarterly, 18(3), 299-318.

Bunge, M. (1979) Treatise on Basic Philosophy, Vol. 4: Ontology 2: A World of Systems, Reidal, Boston.

Chang, K.-C., Lie, T., & Fan, M.-L. (2010). The impact of organizational intervention on system usage extent. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 110(4), 532-549.

Davis, F. D. (1989), ‘Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology’, *MIS Quarterly,* 13 (3), 319-340.

De Raadt JDR. (1989) Multi-Modal Systems Design: a concern for the issues that matter. Systems Research, 6 (1), 17-25

DeLone, W. H., & McLean, E. R. (1992). Information Systems Success: The Quest for the Dependent Variable. Information Systems Research, 3(1), 60-95.

DeLone, W. H., & McLean, E. R. (2003). The DeLone and McLean Model of Information Systems Success: A Ten-Year Update. Journal of Management Information Systems, 19(4), 9-30.

Devaraj, S., Easley, R. F., &Crant, J. M. (2008). How does personality matter? Relating the five-factor model to technology acceptance and use. Information Systems Research, 19(1), 93-105.

Dooyeweerd H. (1955). A new critique of theoretical thought (Vols. 1-4). Jordan Station, Ontario, Canada: Paideia Press.

Dooyeweerd, H. (1979) Wedge Publishing Company, Toronto, Canada.

Eriksson DM. (2001). Multi-modal investigation of a business process and information system redesign: a post-implementation case study. Systems Research and Behavioral Science 18 (2), 181-196.

Green T R G, Petre M, (1996), “Usability analysis of visual programming environments: a cognitive dimensions framework”, Journal of Visual Languages and Computing, v.7, 131-174.

Habermas, J. (1986) The Theory of Communicative Action; Volume One: Reason and the Rationalization of Society, tr. McCarthy T, ISBN 1-7456-0386-6, Polity Press.

Hartmann, N. (1952) The New Ways of Ontology, Chicago, University Press.

Hennington, A. (2007). Understanding IS Impacts in Mandatory Environments: Usage, Compatibility Beliefs, Stress and Burnout. Paper presented at the Americas Conference Conference on Information Systems.

Holden, R. J. (2010). Physicians’ beliefs about using EMR and CPOE: In pursuit of a contextualized understanding of health IT use behavior. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 79(2), 71-80.

Ives, B., &Jarvenpaa, S. L. (1991). Applications of Global Information Technology: Key Issues for Management. MIS Quarterly, 15(1), 33-49.

Joneidy, S. &Basden, A. (2011). Exploring Dooyeweerd’s Aspects for Understanding Perceived Usefulness of Information Systems. – details to be supplied by IIDE/CPTS editors.

Kuhn, T.S. (1970) The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Univ. Chicago Press.

Lee, T. M., & Park, C. (2008). Mobile Technology Usage and B2B Market Performance Under Mandatory Adoption. Industrial Marketing Management, 37(7), 833-840.

Lin, H.-F. (2010). An investigation into the effects of IS quality and top management support on ERP system usage Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 21(3), 335-349.

Linders, S. (2006). Using the Technology Acceptance Model in determining strategies for implementation of mandatory IS. Paper presented at the 4th Twente Student Conference on IT, Enschede, University of Twente.

Lou, H., McClanahan, A., & Holden, E. (1997). Mandatory Use of Electronic Mail and User Acceptance. Mid-American Journal of Business, 12(2), 57-61.

Maslow, A. (1943) A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50, 370-396.

Mishra, A. N., &Agarwal, R. (2009). Technological Frames, Organizational Capabilities, and IT Use: An Empirical Investigation of Electronic Procurement. Information Systems Research, 1-22.

Mirijamdotter A., Bergvall-Kåreborn B. (2006) An Appreciative Critique and Refinement of Checkland’s Soft Systems Methodology. pp.79-102 In: Strijbos S. and Basden A. (eds.) In Search of an Integrative Vision for Technology: Interdisciplinary Studies in Information Systems. Springer.

Ram, S., & Jung, H.-S. (1991). “Forced” Adoption of Innovations in Organizations: Consequences and Implications. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 8(2), 117-126.

Rouibah, K., Hamdy, H. I., and Al-Enezi, M. Z. (2009), ‘Effect of management support, training, and user involvement on system usage and satisfaction in Kuwait’, *Industrial Management & Data Systems,* 109 (3), 338-356.

Shih, Y. Y., & Huang, S. S. (2009). The actual usage of erp systems: An extended technology acceptance perspective. Journal of Research and Practice in Information Technology, 41(3), 263-276.

Singletary, L. L. A., Akbulut, A. Y., & Houston, A. L. (2002). Innovative Software Use After Mandatory Adoption. Paper presented at the Proceeding of 8th Americas on Information Systems (AMCIS).

Tong, Y., Teoy, H.-H., &Tanz, C.-H. (2008). Direct and Indirect Use of Information Systems in Organizations: An Empirical Investigation of System Usage in a Public Hospital. Paper presented at the International Conference on Information Systems.

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425-478.

Ward, K. W., Brown, S. A., & Massey, A. P. (2005).Organisational Influences on Attitudes in Mandatory System Use Environments: A Longitudinal Study. International Journal of Business Information Systems, 1(1), 9-30.

Webster (1975). Webster’s Third Intenational Dictionary Unabridged. Encyclopaedia Britannica Inc, Chicago, USA.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning and Identity. UK: Cambridge University Press.

Winfield MJ., Basden A., Cresswell I. (1996) Knowledge elicitation using a multi-modal approach. World Futures, 47, 93-101.

Yousafzai, Sh Y., Foxall, G R. and Pallister, J G.(2007), “Technology acceptance: a meta-analysis of the TAM: Part 1”, Journal of Modelling in Management,Vol.2 No.3, pp.251-280.

Yu, P., Gandhidasan, S., & Miller, A. A. (2010). Different usage of the same oncology information system in two hospitals in Sydney – Lessons go beyond the initial introduction. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 79(6), 422-429.