ISSA Proceedings 2010 – Argumentative Topoi For Refutation And Confirmation

Long lists of topoi fill the manuals of classical rhetorical theory. There are topoi for the person and topoi for the act. There are topoi for encomia and topoi for the defence. Such lists are teaching devices designed to teach students particular aspects of the art of rhetoric. The lists are numerous, each author producing his own list. Within the realm of rhetoric topoi are a repeated theme, and the discussion usually concerns which topoi best suit each particular circumstance. The topoi for argumentation are taught in the two rhetorical exercises called “refutation” and “confirmation”. This paper will focus on six topoi from these rhetorical exercises suggesting that they are better for teaching argumentation to students than some modern approaches to argumentation.

Long lists of topoi fill the manuals of classical rhetorical theory. There are topoi for the person and topoi for the act. There are topoi for encomia and topoi for the defence. Such lists are teaching devices designed to teach students particular aspects of the art of rhetoric. The lists are numerous, each author producing his own list. Within the realm of rhetoric topoi are a repeated theme, and the discussion usually concerns which topoi best suit each particular circumstance. The topoi for argumentation are taught in the two rhetorical exercises called “refutation” and “confirmation”. This paper will focus on six topoi from these rhetorical exercises suggesting that they are better for teaching argumentation to students than some modern approaches to argumentation.

First the term topos and its relationship to argumentation theory should be explained. A topos in Greek is literally a “place” for finding arguments. The “place” is often understood metaphorically as a “place” in the mind, and topoi can refer to many different kinds of mental places. Sara Rubinelli has made a distinction among the different kinds of strategies in classical rhetoric covered by the term topos. The term can be an indicator of the subject matter the orators might take into consideration for pleading their causes. Topos can also designate a certain argument scheme that focuses on the process of inference, such as the argument from the contrary. According to Latin rhetoricians, locus communis designates a ready-made argument that can be re-used by other speakers (2006, pp. 253-272).

Michael Leff looks back at his forty years of studying rhetorical invention in a recent article where he concludes that the topoi are an ambiguous and multi-faceted concept, sometimes referring to modes of inference, sometimes to aspects of the subject, sometimes to the attitudes of an audience, sometimes to types of issues and sometimes to headings for rhetorical material. Leff points to Boethius and the difference between the dialectical and the rhetorical tradition as an explanation for the many meanings of topos. The subject matter of dialectics is theses, i.e., an abstract question without connection to any particular circumstance. The subject matter of rhetoric is hypotheses, questions concerning particular circumstances. Dialectic is interested in argumentation as such; rhetorical theory is concerned with arguments on specific topics for specific audiences (2006, p. 205).

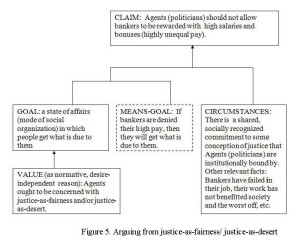

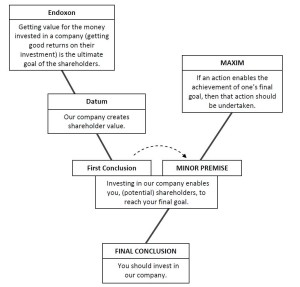

Modern approaches to argumentation usually follow the dialectic tradition and study argumentation divorced from the context. In Garssen’s view, the classical concept of topos in rhetoric and dialectic corresponds to argument schemes. The function of argument schemes is to designate different principles of support that link the argument to the standpoint. Pragma-dialectical argumentation theory classifies argument schemes in three main categories: symptomatic argumentation of the “token” type, comparison argumentation of the “resemblance” type and instrumental argumentation of the “consequence” type (2001, p. 82, 91). Critical discourse analysis also views topos as argument schemes. Wodak has, for example, a table of strategies of justification and relativisation with lists of argumentation schemes including topos of ignorance, topos of comparison, topos of difference, and topos of illustrative example. (Wodak, 1999, pp. 36-42). It should be pointed out that the argument schemes in these modern approaches to argumentation are analytic results from argumentative texts. They were not designed for teaching argumentation. It is questionable whether learning long lists of argumentative nomenclature do actually help students develop their own argumentation.

One difference between the dialectical tradition, including the above mentioned modern approaches, and the rhetorical tradition, is that the former tends to view the argumentative topoi as a product of an analytical examination, while the latter views them as a process for finding arguments in particular contexts. The Italian humanist Giambattista Vico lamented already three hundred years ago that:

“In our days …. Philosophical criticism alone is honoured. The art of ‘topics’ is utterly disregarded … This is harmful, since the invention of arguments is by nature prior to the judgment of their validity … so in teaching, invention should be given priority over philosophical criticism” (Vico, 1709/1990, p. 14). Crosswhite laments that what was true in 1709 is still true today. Criticism and analysis are usually treated as the whole of invention. “Invention is rarely explored as being in some way prior to analysis and criticism” (Crosswhite, 2008, p. 176).

This problem is well known to Quintilian. When he comes to the “places” of arguments, he corrects other rhetoricians: “I do not use this term in its usual acceptance, namely commonplaces, directed against luxury, adultery and the like, but in the sense of the secret places where arguments reside, and from which they must be drawn forth. For just as all kinds of produce are not provided by every country, and as you will not succeed in finding a particular bird or beast, if you are ignorant of the localities where it has its usual haunts or birthplace, … so not every kind of argument can be derived from every circumstance, and consequently our search requires discrimination” (Inst. V.10.21). Leff comments that from Quintilian’s perspective, topics are not theoretical principles. “They are precepts that have potential application to accrual cases, and their most important function is as a training device.” Proper use of the topics helps to develop a capacity for arguing in precisely those situations where theory offers the least guidance. The theoretical tradition therefore does not help if one wants to find the function of topoi. In recent years Leff consequently has paid more attention to the rhetorical handbook tradition, such as the progymnasmata (2006, pp. 208-209).

1. The Progymnasmata

The progymnasmata are a set of preliminary rhetorical exercises designed to teach students the art of rhetoric. A gymnasma is an exercise and the word refers to physical exercises as well as mental exercises, the plural gymnasmata refers to a set of exercises. Isocrates comments that just as we need exercises to train the body, we also need exercises to train the mind, Antidosis 180-185. The progymnasmata originated in Hellenistic times and came to dominate the early stages of Roman rhetorical training and had a tremendous influence on rhetorical teaching in the renaissance. The main versions of progymnasmata come from Theon (first century CE), Hermogenes (second century CE) and Aphthonius (fourth century CE), see the translations by Kennedy (2003). The progymnasmata have been used throughout the schools of western civilisation and Gert Ueding even calls them the “Lehrplan Europas”.

The Aphthonian set of fourteen exercises has had the most influence. Manfred Kraus has found more than 400 different editions of Aphthonius in European renaissance. The set starts with easy exercises like retelling a fable and telling a story. Next come the chreia and maxim which develop a theme with a set of topoi. More advanced exercises are the encomion, comparison, characterization, description and thesis, which all prepare the students for the declamation at which the students take a stand on particular argumentative issues. The teaching idea behind the progymnasmata is described by Fleming (2003, pp. 105-120).

Progression in learning through the use of topoi is the central ideas behind the progymnasmata. The students are taught a topical way of thinking about rhetoric. The topoi come in many forms in the progymnasmata. When composing narratives, students should consider the six attributes of narrative; the person who acted, the thing done, the time at which, the place in which, the manner how and the cause for which it was done (Aphthonius 2.23-3.2). Theon (78.16) calls them the stoicheia or basic elements of the narrative. To learn how to compose a narrative the student should make sure that all these attributes were covered. When he would write a chreia he would have to develop the meaning of an utterance or action with a set of topoi; first, a praise of the person who uttered the saying or performed the action, then a paraphrase of the meaning in his own words, then a reason, an argument from the contrary, a comparison, an example, a testimony from reputable people and a brief conclusion. These topoi are called kefalaia, “headings” for developing a subject.

The basic training in argumentation occurs in the combined exercises “refutation” and “confirmation”, number five and six in the series. The exercises presuppose that the students know how to tell a story from different perspectives and how to use topoi like the contrary, example, analogy and witness from other persons. Students typically refute and confirm the meaning of a narrative. This means that the students first must interpret the meaning of the narrative, typically a mythological story, analyze it and then write a small text as the basis for an oral performance in the class room. The process is hence both analysis and composition. To accomplish this task the students are given a set of six topoi that will guide them through the learning process. These topoi are ‘the clear’, ‘the persuasive’, ‘the possible’, ‘the logical’, ‘the appropriate’ and ‘the advantageous’. Each of these topoi is accompanied by its opposite so that the student will look both for the clear and the unclear, for the persuasive and the unpersuasive, for the possible and the impossible, the logical and the illogical, the appropriate and the inappropriate, the advantageous and the disadvantageous. This way the students are taught the practise of two-sided arguments.

2. The clear

The first topos is ‘the clear’ and ‘the unclear’. Using this topos the students start their interpretative process by clarifying the issue. If the subject studied was a narrative, maybe a mythological story, the interpretation of the meaning of the story would be the first part of the process. In the rhetorical perspective, stories are ways of describing human activity from a certain perspective. To analyse the perspective chosen by the narrator, the student could use the topoi from the previous exercise ‘narrative’: the person, the act, the time, the place, the means and the reason for the human activity. Such topoi would be pertinent in juridical cases where the background of the proposed crime would be given in the narratio of the speech. If these narrative topoi were used as questions to the text and the answer was satisfactory, then the narrative could be described as clear. Theon comments that the narration becomes clear from two sources: from the subjects that are described and from the style of the description of the subjects (2003, pp.29-30). Lack of clarity comes in many forms. A statement would be unclear if the wording does not express the meaning behind the words. In rhetorical theory clarity is a virtue of style as well as a topos for argumentation. In the rhetorical view of argumentation the linguistic expression is intimately connected with the argumentative content. So for example, Kraus argues that the rhetorical figure contrarium is also an argument (2007, pp. 3-19). Form and content cannot be separated. Muddled thinking cannot be expressed in a clear style.

When a student would use the topos ‘the clear’ he would try to determine the argumentative content behind the linguistic expression. The interpretation of arguments and the reconstruction of argumentation is a complicated process, some of the problems involved are described by van Rees (2001, pp. 165- 199). Under this topos, could also be listed such sub-topoi as the determination of the actual wording of the source criticised. Was the source quoted correctly? Was the translation correct from the original language? Under “clarity” we could also include interpretations of words and definition of terms.

The topos also has its opposite ‘the unclear’. Expressions that are ambiguous and obscure are a sign of unclear thoughts. Looking for unclearness in the linguistic form teaches the students the need for a good language, as to spelling, choice of words and stylistic level.

3. The persuasive

The second topos is ‘the persuasive’ and ‘the unpersuasive’. There is an analytical move from text to context in this process. Once the student has made a preliminary interpretation of the meaning of the statement, customarily contained in a story, he is advised to consider the audience for whom this statement would be persuasive. For whom would this be credible? Who would believe this story? The Greek term to pithanon, used by Aphthonius, is the same word as Aristotle uses in his famous definition of rhetoric, “Let rhetoric be defined as an ability in each particular case to see the available means of persuasion” (Rhet. 1.2.1). Aristotle also comments that “the persuasive is persuasive in reference to someone” (Rhet. 1.2.11). The argument is not a good argument unless it persuades the intended audience.

The centrality of the audience is also emphasized in modern versions of argumentation. In the New Rhetoric by Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca the premises of the audience are the starting point for argumentation. The pragma-dialectical understanding of argumentation also includes a reference to an audience when it defines argumentation as “convincing a reasonable critic of the acceptability of a standpoint” (van Eemeren, 2004, p. 1).

Subtopics to the topos ‘the persuasive’ would be different kinds of analysis of the audience. Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca call the premises held by the universal audience premises relating to reality and divide them into facts, truths and presumptions. The premises relating to that which is preferable to particular audiences can be divided into values, value hierarchies and loci, a preference for one abstraction rather than another. Other kinds of analyses of the audience would be opinion polls, interviews and surveys.

This emphasis on the audience in rhetorical theory draws a line between what is true and what is persuasive. Quintilian comments that some people criticise him for suggesting “that a statement which is wholly in our favour should be plausible, when as a matter of fact it is true”. It is not enough that a statement is true, it must also be credible since “There are many things which are true, but scarcely credible, just as there are many things which are plausible though false” (Inst. IV.2.34). To make sure that the narrative will be credible to the audience he recommends that the speaker should: 1) take care to say nothing contrary to nature; 2) assign reasons and motives for the facts on which the inquiry turns; 3) make the characters of the actors in keeping with the facts we desire to be believed; 4) do the same with place and time and the like (Inst. IV.2.52). These points could serve as subtopics to determine whether a narrative is credible or incredible.

Form and content cannot be separated in rhetorical theory. Res and verba are intimately connected. As students are looking for what is persuasive in the narrative analysed they should also remember that credibility or persuasiveness is the third virtue of style for the narration. And they are well advised to remember this lesson when they prepare their own composition.

As noted above, the point with the topos ‘persuasive’ is not the factual veracity of the statement; correspondence with extra-linguistic reality is beyond the purview of most rhetorical theories. This second topos is also not the same as the probable; probability theory belongs to the field of statistics. But that which happens often is likely to happen again. People are often the same in different circumstances. History tends to repeat itself. Looking for that which is common, usual, customary is therefore one way of finding that which is persuasive. It is reasonable to look for similarities in behaviour patterns.

4. The possible

The third topos is ‘the possible’ and ‘the impossible’. The previous topos ‘the persuasive’ emphasised the audience and their frames of reference; now ‘the possible’ emphasises the physical world and its limitations. In Greek the topos is to dynaton, that which can be done. Using this topos the student asks whether the statement is possible. Can it be done? Are there obstacles that would make the proposed action impossible to accomplish in the future or to have been performed in the past? In a juridical context, where so much of classical rhetorical theory comes from, the prosecutor and the defence would argue whether the action could have been done considering the circumstances of the persons involved, the time, the place, the manner and the reason for the action, usually called the motive.

When the action proposed is in the future, a political issue in rhetorical theory, the deliberation would consider different obstacles to the proposal. Are there sufficient resources, economic or material? Are there other factors at work that would hinder the accomplishment? Are there legal complications? Quintilian remarks that the third consideration for deliberative oratory [besides honour and expediency] is to dynaton or possible. “The practicality of the matter under discussion is either certain or uncertain. In the latter case this will be the chief, if not the only point for consideration” (Inst. III.8.16). The topos of the possible could also be used today when teaching students argumentation. Possibility is still an issue and we could use the various connotations of the words “optimist” and “pessimist”. The optimist would see the various possibilities in a case and might see himself as a possibility thinker. The pessimist would see the obstacles and the difficulties, and he would probably call himself a realist.

5. The logical

The fourth topos is the logical and the illogical. Using this pair of topoi the student would look at the mode of reasoning in the argumentation. The Greek term for the topos is to anakolouthon which literally means “that which does not follow”. The wording suggests that the parts of the argument should follow from one another, that the reasoning should be coherent. As an argumentative topos “that which does not follow” scrutinizes the relationship between the terms in the reasoning. The focus is especially the implied premises from which the reasoning does not follow. The topos helps to make the implied premises explicit, a basic step in an analysis of argumentation. In formal logic non sequitur, the Latin translation of to anakolouthon, is an argument in which the conclusion does not follow from the premises. The non sequitur concerns the formal validity of the reasoning. In this type of argument the conclusion can be either true or false, but the argument is fallacious because there is a disconnection between the premise and the conclusion. All formal fallacies are special cases of non sequitur.

When a student would use this topos he would look for fallacies in the argumentation. The topos can be used both for analysing argumentation from someone else and for preparing the student’s own argumentation. When the student has scrutinized the coherence of the argumentation he wishes to put forward, he has probably found some fallacies and some logical inconsistencies. When the student has corrected the fallacious reasoning, he should have a watertight argument. This process of looking for fallacies is the process of using the topos of the logical. Fallacies are central to the pragma-dialectical school. It is interesting to note that formal validity is not the primary concern but comes as number four out of six topoi in the progymnasmata.

The coherence in thought corresponds to coherence in style. An anacoluthon is a grammatical term for when a sentence abruptly changes from one structure to another. The sentence is not completed as it started when the introductory elements of a sentence lack a proper object or complement. This is a grammatical error and should usually be avoided, but since rhetorical style is adapted to the particular situation, strict adherence to rules is not always recommended. In rhetoric an anacolouthon is therefore regarded as a conscious choice of style, a rhetorical figure that shows excitement, confusion, or laziness.

6. The appropriate

The fifth topos is ‘the appropriate’ and ‘the inappropriate’. These terms emphasize the importance of the rhetorical situation. Behind these terms we find the Greek to prepon “that which is fitting”. Lausberg comments that to prepon relates both to outward circumstances and moral fitness (1998, p. 1055). It is the virtue of the parts in fitting themselves harmoniously together as a whole. The verb is used for what seems right to the eye in the situation. In Latin the corresponding terms are aptum and decorum. Other English translations would be ‘the suitable’, ‘the seemly’, ‘the proper’, or ‘the decent’. The form and the content are two sides of the coin in rhetorical theory and therefore the rhetorical concept of prepon has an inner dimension relating to the components of the speech that should be in accordance with one another and an external prepon which concerns the relationship between the speech and the social circumstances of the speech. Quintilian treats both levels of aptum extensively (Inst XI.1.1-93). “For all ornament derives its effect not from its own qualities so much as from the circumstances in which it is applied, and the occasion chosen for saying anything is at least as important a consideration as what is actually said (Inst. XI.1.7).

Considerations of aptum lead the student to consider social and cultural conventions. In rhetorical theory considerations of the rhetorical situation have been a major point of interest since Bitzer’s groundbreaking article (Bitzer, 1968). Does the context of the argument have a place in a modern theory of argumentation? On this issue it is interesting to note that the definition of a fallacy has changed in the pragma-dialectical school. According to the standard definition of a fallacy, accepted until recently, a fallacy was considered to be “an argument that seems valid but is not”. This classic definition restricts the concept of fallaciousness to patterns of reasoning and formal validity, and neglects the fact that many fallacies are not included. Therefore a broader definition was adopted: “deficient moves in argumentative discourse,” (van Eemeren, 2001, p. 135). In his more recent writings van Eemeren, together with Houtlosser, has attempted to bridge the gap between dialectical and rhetorical views on argumentation by the concept of strategic manoeuvring, which is an attempt to find the most expedient choice of arguments to seek successful persuasion (van Eemeren, 1999). Strategic manoeuvring also leads him to redefine fallacies as “violations of critical discussion rules that come about as derailments of strategic manoeuvring” (van Eemeren, 2006, p. 387). This is a clear example of taking the rhetorical situation into consideration in argumentation.

Quintilian comments on speakers who break the social and cultural conventions of aptum. They use offensive and distasteful language, upset the hearers by the wrong level of style and use the wrong type of emotions. “An impudent, disorderly or angry tone is always unseemly, no matter whom it is who assumes it”. Vices of a meaner type are “grovelling flattery, affected buffoonery, immodesty in dealing with things or words that are unseemly or obscene, and disregard of authority on all and every occasion” (Inst. XI. 1.29-30).

Are considerations of social and cultural conventions legitimate concerns in a theory of argumentation? For a rhetorical theory of argumentation, which is concerned, not with abstract argumentation schemes, but with specific argumentation addressed to particular audiences, the rhetorical situation is the central concern. Politeness and offensiveness therefore should be concerns for a rhetorical theory of argumentation.

Students using the topos “the appropriate” would look for aspects of the case they are analysing that would be in accordance with social and cultural norms. The topos would also help the student to find elements in the analysed story, or in the position put forward by the other side, that would be inappropriate or offensive. Having analysed the rhetorical situation of someone else, the student would be ready to consider his own rhetorical situation as he performs the analysis he has prepared. What are the expectations in the class room? What norms apply? And what norms are governing the public discourse outside the class room? Political correctness is a prevailing issue even today and should therefore be taken into account in a theory of argumentation..

7. The advantageous

The sixth topos is ‘the advantageous’ and ‘the disadvantageous’. Using this topos the student asks who benefits from the proposed action. The Greek to sympheron refers to the goal of the argumentation in deliberative rhetoric. The political speaker seeks to present his proposal as advantageous to the audience. This advantage could be long or short range, and could concern a particular group or the common good. The advantage could be material or concerned with honour and prestige. Aristotle comments that “the end of the deliberative speaker is the expedient, to sympheron, or the harmful”. The political speaker recommends the expedient and dissuades the audience from doing what is harmful. “All other considerations, such as justice, and injustice, honour and disgrace, are included as accessory in reference to this” (Rhet 1.3.5).

The Latin translation of the term is utilitas. The term ‘utility’ in English, together with words like ‘expedience’, ‘interest’, ‘benefit’, ‘gain’ and ‘profit’, would be variations of this topos. When a student would use this topos, he would engage in a simple form of what we would call ideological critique. Behind every story and statement we can suspect that there is some kind of interest hidden. Using the topos ‘advantage’ the student would ask for the real motive and who would gain by the suggested action.

8. Hermogenes’ example

Hermogenes gives an example of how a student could use the six topoi in refutation:

“You will refute by argument from what is unclear, implausible, impossible; from the inconsistent, also called the contrary; from what is inappropriate, and from what is not advantageous. From what is unclear; for example, “The time when Narcissus lived is unclear.” From the implausible, “It was implausible that Arion would have wanted to sing when in trouble.” From the impossible; for example, “It was impossible for Arion to have been saved by a dolphin.” From the inconsistent, also called the contrary, “To want to destroy the democracy would be contrary to wanting to save it.” From the inappropriate, “It was inappropriate for Apollo, a god, to have sexual intercourse with a mortal woman.” From what is not advantageous, when we say that nothing is gained from hearing these things,” (2003, p. 179).

9. Argumentation with the topoi

Hermogenes’ example shows how the argumentative topoi can function like an argument machine. The student could always say that the position he would refute is unclear, unpersuasive, impossible, illogical, inappropriate and disadvantageous. And when he would confirm his own position, he could always say that it is clear, persuasive, possible, logical, appropriate and advantageous. The problem for such a simplistic view of these topoi is that the rhetorical situation of the progymnasmata is not taken into account. Refutation and confirmation are class room exercises designed to teach two sided arguments. In the class room there would be other students prepared to speak on the same issue, but from the opposing point of view. In such a circumstance it is not enough to state that the issue is clear to yourself, you have to convince the opposing party of the clarity of your position. It is not enough to blame the other side for muddled thinking, you must also on the spur of the moment, in the class room, with the other students as a critical audience show the lack of clarity you claim to be able to find in the argumentation from the opposing side.

This is a sophistic approach to argumentation known to the ancient Greeks as antilogic and to Romans as controversia. The most influential representative of Sophistic education was Protagoras, who began his textbook Antilogiae with the famous dictum that “on every issue there are two arguments (logoi) opposed to each other on everything” (Sprague, 1972, p.4). This concept was the core of Sophistic pedagogy, and Marrou notes that it was “astonishing in its practical effectiveness” (1956, p. 51). Cicero summarizes the use of controversia in the Hellenistic Academy as follows: “…the only object of the Academics’ discussions is by arguing both sides of a question to draw out and fashion something which is either true or which comes as close as possible to the truth,” Academica 2.8. Mendelson has shown how Quintilian makes this form of argumentation his own pedagogy of argument. Quintilian exemplifies the method in his own writing when he constantly brings in opposing viewpoints and weighs pro’s and con’s against each other on every issue (2001, pp. 279-282.) The purpose of the rhetorical training was facilitas, the resourcefulness and spontaneity acquired from continual interaction with other discourse. To be able to speak on both sides of the issue, in utramque partem, is at the heart of rhetorical education. This is where the progymnasmata come in. The learning outcome for these exercises is that the students would be able to perform speeches and argumentation on the spot. They should have acquired this ability so that they had the competence ingrained in them.

10. A good topical system

Karl Wallace, nestor in the Speech community, in an important article published in 1972 pondered the problem of topoi and rhetorical invention. Wallace comments that Perelman’s work has limited application if we aim to construct a system of topics that is teachable to unsophisticated learners. He specifies certain parameters for a good topical system. Such a system of topoi should be both inventive and analytic. It should aid the communicator to find materials and arguments as well as helping the listener and critic to understand and evaluate messages. It should serve as an instrument of recall and recollection as well as stimulate inquiry by revealing sources of ignorance. It should prompt ideas by appealing to meanings that have become symbolized in the language of speaker, writer, and audience. A good topical system should have the power to call up appropriate linguistic structures, as well as subject matter. How broad should such a topical system be? Wallace concludes that it must be sufficiently general to cut across a number of subject matters. Members of the national committee on the nature of rhetorical invention wanted something truly “generative”, something that would be so powerful and far-reaching that it would breed not one system of topics, but many: Something that would have the power of modifying and correcting topics from one generation to another.

The simple proposal of this paper is that the six argumentative topoi in the progymnasmata, the clear, the persuasive, the possible, the logical, the appropriate and the advantageous, fulfil these requirements for a good topical system. The list is relatively short and it cuts across a number of subject matters. The list is truly generative and breeds many systems of topics. The six topoi combine stylistic form and argumentative content. There is a progression in the series that concerns the inventive process of gathering content. The six topoi can also function as the basic outline for the disposition for a short argumentative text. And they also teach the students the art of arguing on both sides of an issue, in utramque partem. Therefore the argumentative topoi for refutation and confirmation are better for teaching argumentation to students than the modern approaches to argumentation.

REFERENCES

Apthonius (2003). Progymnasmata. In G. Kennedy (Trans and Ed). Progymnasmata: Greek Textbooks of Prose Composition and Rhetoric (pp. 89-127), Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature.

Aristotle (1991). Aristotle on Rhetoric: A Theory of Civic Discourse. G. Kennedy (Trans). New York: Oxford University Press.

Bitzer, L. (1968). The Rhetorical Situation. Philosophy and rhetoric1, 1-14.

Cicero (1933). Academica. H. Rackham (Trans). Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Crosswhite, J. (2008). Awakening the Topoi: Sources of Invention in the New Rhetoric’s Argument Model. Argumentation and Advocacy 44, 169-184.

Eemeren, F.H. van, & Houtlosser, P (1999). Strategic Manoeuvring in Argumentative Discourse. Discourse Studies 1, 479-497.

Eemeren, F.H. van, & Houtlosser, P (2006). Strategic Maneuvring: A Synthetic Recapitulation. Argumentation 20, 381-392.

Eemeren, F.H. van (2001). Fallacies. In F.H. van Eemeren (Ed.) Crucial Concepts in Argumentation Theory, (pp. 135-164), Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Eemeren, F.H. van, & Grootendorst, R. (2004). A Systematic Theory of Argumentation: The Pragma-Dialectical Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fleming, J. D. (2003). The Very Idea of a Progymnasmata. Rhetoric Review 22, 105-120.

Garssen, B. (2001). Argument schemes. In F.H. van Eemeren (Ed.) Crucial Concepts in Argumentation Theory, (pp. 81-99), Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Hermogenes. (2003) Progymnasmata. In G. Kennedy (Trans and Ed). Progymnasmata: Greek Textbooks of Prose Composition and Rhetoric (pp.73-88), Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature.

Isocrates, (1929). Antidosis. In G. Norlin (Ed.) Isocrates in three volumes. Loeb Classical Library. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass.

Kraus, M. (2007). From Figure to Argument: Contrarium in Roman Rhetoric. Argumentation 21, 3-19.

Lausberg, H. (1998). Handbook of Literary Rhetoric: A Foundation for Literary Study. Leiden: Brill.

Leff, M. (2006). Up from Theory: Or I Fought the Topoi and the Topoi Won. Rhetoric Society Quarterly 36, 203-211.

Marrou, H.I. (1956). The History of Education in Antiquity. G. Ward (Trans). New York: Sheed and Ward.

Mendelson, M. (2001). Quintilian and the Pedagogy of Argument. Argumentation 15, 277-293.

Perelman, C., & Olbrechts-Tyteca L. (1969). The New Rhetoric: A Treatise on Argumentation. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

Quintilian, M.F. (1920-22). The Institutio Oratoria. Four volumes H.E. Butler (Trans.). Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Rees, M.A. van (2001). Argument Interpretation and Reconstruction. In F.H. van Eemeren (ed.) Crucial Concepts in Argumentation Theory, (pp. 165- 199), Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Rubinelli, S. (2006). The Ancient Argumentative Game: Topoi and loci in Action. Argumentation 20, 253-272.

Sprague, R. K. (1972). The Older Sophists: A complete translation by several hands of the fragments in “Die Fragmente der Vorsokratiker”, ed. by Diels-Krantz, Columbia: University of South Carolina Press.

Theon, A. (2003) Progymnasmata. In G. Kennedy Trans and Ed. Progymnasmata: Greek Textbooks of Prose Composition and Rhetoric (pp.1-88), Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature.

Vico, G. (1990). On the study of methods of our time. (E. Gianturoco, Trans.) Ithaca: Cornell University Press. (Original work published in 1709).

Wodak, R, et al (1999). The Discursive Construction of National Identity. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.