1. Introduction

1. Introduction

Preservation of patient autonomy in clinical decision-making is strongly advocated in Western models of medical practice. Ensconced in a physician’s legal and moral responsibility is a duty to ensure the patient receives objective and impartial information that will support his/her ability to make an informed choice. Yet, there is a subtle disparity between ‘presentational’ and ‘persuasional’ strategies of providing information on risks and benefits in therapeutic decision-making (Fisher 2001). The process of informed consent, while institutionally sanctioned, is subject to social and political influences (Goodnight, 2006).

Like all institutional practices, doctor-patient interactions feature bounded communicative rationality. In order to reach an informed agreement, participants in a discussion may in principle appeal to ideal norms of consensus formation. In the routines of reasonable practice, such norms are constrained by the conventions, boundaries, interests and customs of an institutionally regulated forum. In the case of medical consultation, the interests of time and resources engage provider and client in a reciprocal exchange of argumentation, but from quite different perspectives, with different risks at stake. At the ontological level, a patient has his or her health to consider. At the professional level, a doctor has a duty to do no harm, a practice to consider, as well as state of the art credentials backed by peer review and licensing. If the consultation is productive, different risks are minimized for both doctor and patient. Presumably, presumption – the right to question sufficiency of evidence and to say no – resides with the patient because his or her risks involve the less reversible outcomes of mortality. Best practices should be reviewed critically to evaluate communication norms, recognizing that such standards change over time because medical care evolves, state and private programs transform, and aspects of the human condition alter.

2. Biopolitics in the medical domain

The relationships between the institutions of medicine and the conventions of health constitute a subfield of the broader area of biopolitics. State regulations, scientific research, professional training, and public participation configure standing best practices for this field that maintains, as a core feature, the communicative exchange between doctor and patient. Schulz and Rubinelli (2008) define the “doctor-patient interaction” as “an information-seeking dialogue” where ideally a reasonable exchange occurs between requests for and provision of information to support the doctor’s principal goal to convince the patient of most likely diagnosis or best treatment option. Yet, the therapeutic relationship between a doctor and a patient is an iterative process complicated by the potential for emerging uncertainty and probability in medical discourse (Gilbert & Whyte 2009; forthcoming). The ‘reasonable’ exchanges in medical practice typically occur in the form of deliberative discussion where the future is not entirely known, relevant evidence is gathered and assessed, options evaluated, and a decision reached or deferred (Goodnight, 2006).

In an unfettered dialogue, conversation may follow the norms of exchange defined by normative approaches to argumentation, such as pragma-dialectics. Then, conversational rules are embedded resources of critical appeal used to reach and refine an informed agreement. In domains of practice, such as medicine, these norms are bounded by context. In the situated deliberations of medical consultation, Schultz and Rubinelli (2008) point out, asymmetries of doctor-patient interests result in discussions that depart from but are accountable to ideal norms. Departures due to unequal expertise, availability of time, and risk are nevertheless justified within the conventional practices of medicine. The practices of such biopolitics invite critical inquiry into how greater symmetries – that empower the doctor or the patient as needed – are reaffirmed or change.

Institutions that are relatively stable may develop known and trusted settings for communication. The forums of practice are legitimated by professional roles and habits of advocacy that sustain and develop over time in ways that accommodate the needs of more inclusive publics. From time to time, institutional practices undergo shocks. New changes unsettle what is taken for granted as legitimate practices underwriting trustworthy communication. Modern medicine is in a state of rapid change due to the development of research and new options for treatment. Holmer reports that there are “more than 1000 new medicines in development – for Alzheimer disease, cancer, heart disease, stroke, infectious diseases, AIDS, arthritis, Parkinson disease, diabetes, and many other diseases – promising even more effective treatments and better outcomes in the future” (1999, p. 382). Trained doctors must master new medical options and techniques through reading journals, conference attendance, and industry detailing. The public faces an even greater educational challenge. Publicity has increased exponentially the amount of information available to the public, as Holmer confirms: “More than 50 consumer magazines about health care appear on the newsstands every month. Many television stations have a physician dispensing medical news. Nearly one quarter of the Internet is devoted to health care information” (Holmer, p. 380).

Medicine has been in a constant state of change, matching traditional remedies against new scientific research and findings. While drug advertising has been around for 300 years, much of it has offered unproven promises sold by ‘snake oil’ rhetoric. For example, between 1708 and 1938, “advertisements for patented medications claming to treat everything from dandruff to infidelity could be found in magazines, newspapers, and traveling medicine shows” (Ghanji, 2008, p. 68). Marketing strategies then changed due to the strict regulation of pharmaceuticals. Dissemination of information about medical care and treatment became regulated by state rules that permitted scientific information in medical journals to guide the decisions of physicians while limiting advertising of prescription miracles to publics. In the 1990s, the expert model was partially dismantled by the United States and New Zealand which permitted direct to consumer (DTCA) advertising. The practice of DTCA has grown even as it remains significantly controversial (Coney, 2002; Mackenzie, Jordens & Ankeny et al., 2007; Vitry, 2007).

We believe that argumentation studies should initiate critical practices in order to appraise the controversy brought about by these growing institutional appeals and examine the potential for advertising to influence the dialogical relationship and deliberative norms of physician-patient engagement. The development of such norms requires critical attention to the consequences of advertising campaigns upon the relative communicative positions of doctor and patients who reason together and argue in the interest of health.

3. Institutional practice ‘in flux’

Biopolitics includes controversies in the critical study of argumentation concerning the risks, resources, and boundaries of medical practices in the pursuit of health. The area includes questions of policy, expertise, and personal decision-making in the social-cultural spaces of influence. Particularly in times of wide-spread changes brought about by research, new technologies, or pressing population health conditions, institutional practices move from steady-state convention to conventions in flux, with resulting debates over the advantages and disadvantages of change. In this respect, David Dinglestad et al (1996) report “drugs are not only widely used but also widely debated.” The question of advertising impacts on patient-doctor exchanges remains highly contested (Calfee, 2002; Gellad & Lyles, 2007; Gilbody, Wilson & Watt, 2005; Hoffman & Wilkes 1999, Rosenthal et al., 2002; Bell et al., 1999a, 1999b, 1999c). Much of the debate poses the economic ambitions of pharmaceutical companies against the kind of cooperative reasoning between doctors. In this respect, patient autonomy is integral to achieving competently fashioned informed consent, weighing the risk benefit of therapeutic intervention, and minimizing the medicalisation of normal human experiences (Mintzes, 2002; Wolfe, 2002; Main et al., 2004).

Recently, the debates have been located primarily in the United States and New Zealand, the only countries where DTCA is fully permitted. In countries where DTCA is prohibited, pharmaceutical companies find other avenues to market their products to consumers; for example, internet, direct mail, meetings with patient groups, consumer targeted websites (Main et al., 2004). As Sweet observes (2010, p.1), “electronic detailing, interactive websites, email prompts and viral marketing campaigns using social networking sites such as YouTube, MySpace and Facebook are among the tools being used”. As the European Community, Canada and Australia ease regulatory changes or face pressures to do so, internet circulation of medical information is making national boundary conditions for practice vulnerable.

The marketing arm of the pharmaceutical industry has sponsored initiatives that have “revolutionized how medical information and treatment options are disseminated to the public” (Bhanji, p. 71). Protagonists argue that such advertising increases the self-diagnosis of conditions that would otherwise go untreated (Main et al. 2004). For example, Donohue and Berdt assert that DTCA “increases awareness and expands the treatment of underdiagnosed conditions, such as hypercholesterolemia and depression” (Donohue and Berdt, 2004, p. 1176). Indeed, DTCA is argued to be “an excellent way to meet the growing demand for medical information, empowering consumers by educating them about health conditions and possible treatments” thereby playing potentially “an important role in improving public health” (Holmer, p. 180).

Antagonists argue that “many pharmaceutical companies” engage in “repeatedly” misleading the public and doctors (Troop and Richards, 2003). While drug companies do meet standards established for informing consumers of risks, critics complain that the risks are not fully disclosed, alternative cheaper options discussed, or much actual public health information provided (Main et al.,. 2004). The net result of DTCA in New Zealand and in the United States has been to increase “medicine enquiries by consumers to prescribers, and subsequent prescribing to consumers” (Rosenthal, 2002). Furthermore, DTCA typically promotes the use of more expensive and newer medications to large consumer populations with chronic conditions (Rosenthal, 2002). The debate continues to evolve. Recently, marketers of DTCA position advertising do not directly recommend to consumers that they take the advertised medication but instead encourage consumers to talk to a doctor about the medication’s costs and benefits. Thus, proponents of DTC advertising argue that it is “an opportunity for improved patient education and may stimulate clinical dialogue with the physician” (Robinson, 2004, p. 427). We are especially interested in considering how DTCA might potentially impact on the deliberative dialogue of clinical practice.

In this sense, these drug debates “are not timeless manifestations of the nature of drugs but rather contingent features of social structure and social struggle” (Dinglestadt et al., 1996). Troop and Richards (2003) proffer an explanation for this problem: “the advertising/marketing and the health paradigms are so very far apart that dialogue and compromise are far from easy. The language of the marketing and advertising arms of industry is characterized by ‘bottom lines’, ‘market share’, ‘brand loyalty’ and ‘disease creation’. These are concepts foreign to most health professionals whose framework is the care of individuals in patient-centered and evidence-based paradigms.”

The combination of new products and increased advertising constitutes an accelerating structural shift in how information is rendered accessible to publics. The result is an ongoing struggle which places the norms of doctor-patient communication at stake. The costs and benefits are complicated. On the one hand, false expectations of new medicines may increase pressures for marginal prescriptions and undermine trust and responsiveness of patients denied these ‘breakthroughs’ by a physician. On the other, advertising performs a public health role; even if the result of advertising is over-prescription and inflated expectations, it is arguably better to influence a class of potential patients to come in for treatment than remain in isolated misery.

So potentially great are the stakes of this influence on practice, that critical intervention into the controversy is warranted. The contextually driven cultural controversies – the biopolitics – that influence drug advertising bear implications for how publics may perceive medical conditions and new norms of interaction with doctors. Case studies of controversies over pressures on institutional practices of professional-client argumentation open the way for: (1) the development of new standards for assessing the intent of health messages posited by advertisers, and (2) the development of standards for clinical communicative competence, so that clinicians might accommodate the impact of biopolitics on the clinician-patient dialogue and, subsequently, clinical determination (outcome). Hence, we contend that biopolitics offers a space for appraising and re-conceptualising institutional norms of reasoned exchange, as in the clinical consultation. We inquire into biopolitics specifically in regard to controversies associated with DTCA and the mental health domain.

4. Advertising for Mental Health

Mental health advertising is a good place to begin critical case studies because it is both prevalent and highly controversial. According to Bhanji, “approximately 20% of the 50 most advertised drugs in the United States were medications used to treat psychiatric and neurologic disorders. Antidepressants, antipsychotics, and anticonvulsants are among the top five most heavily advertised classes of medicine” (Bhanji, 2008, p. 69). The controversy over mental health advertising rests in a long history of debate (Goldman & Montagne, 1986; Seinberg, 1979, Lion, Rega & Taylor, 1979). One of the prominent question in the ongoing debate has centered on whether DTC marketing of psychiatric medications “leads to over-prescribing of more expensive drugs, as critics contend, or de-stigmatizes mental illness and promotes use of effective medications, as proponents claim ” (Bhanji, 2008, p. 68).

The biopolitics of mental illness and medical institutions was changed in the 1950s by the development of tranquillizers and antipsychotics that “made possible for the first time the treatment and control of mentally ill people outside of an institutional setting” (Dingelstad et al., 1996, p. 1829). Now, in most developed countries people suffering or in remission from psychosis are routinely treated in the community. In the 1990s “a new era in the sales of psychotropic drugs began in most western societies” with a “dramatic increase in the sales of antidepressants” (Lovdahl, Riska & Riska, 1999, p. 306).

Reportedly, pharmaceutical companies have substantial “economic interest in maintaining patients on medications for chronic conditions like depression” (Donohue and Berndt, 2004, p. 1176). Pursuing such interests, the pharmaceutical industry appears to emphasize persuasion not information in drug promotion and, in the case of depression, advertisements appear “more unscientific and less informative than other types of drug advertisements” (Quin, Nangle & Casey, 1997, p. 597). Quinn et al. (1997) found that metaphors are used instead of science generally in the area of mental health (Owen, 1992). Hence, depression is frequently “reduced to a simple single entity (darkness) for which there is only one treatment (medication) by which health (sunlight) will be restored” (Quinn et al., 1997; Owen, 1992).

Mental health advertising is controversial on several fronts. First, many advertisements are misleading. For example, in the common advertising of antidepressants, serotonin reuptake inhibitors are frequently promoted using information that is inconsistent with scientific evidence on the treatment of depression (Lacasse, 2005, p. 175). Moreover, while drugs for mental illness are often advertised as non-addictive, the technical distinction in drug advertising materials regularly fails to acknowledge difficulties encountered with withdrawal. Finally, it is not clear that altering body chemistry by itself furnishes a cure for mental illness.

In biosychosocial approaches to mental illness, explanatory models of illness are elicited and negotiated between the clinician and the patient (Bloch and Singh 2001). Ideally, the clinician endeavors to understand the patient’s problem in the context of the patient’s beliefs, cultural lifestyle and norms in order to recommend best treatment for the patient who is expected to comprehend the benefit of and comply with treatment (Andary et al., 2003, p. 137). A process of negotiation is required to reduce the conflicts between the patient’s and doctor’s models in order to reach a “mutually accepted explanatory model” (Andary et al., 2003, p. 141), as cooperation with treatment requires the clinical intervention to match the patient’s explanatory model of illness (Sue & Zane, 1987; Andary et al., 2003). In other words, the negotiated model of illness helps the clinician to justify the treatment and win the patient’s cooperation (Andary et al., 2003, p. 141). In the domain of chronic mental illness, the patient’s explanatory model is rarely static with the chronic nature of mental illness potentially generating conflicts of understanding that evolve an iterative process of therapeutic decision-making. The movement of meaning across the illness experience and dialogic consultation is subject to contemporaneous biopolitics. Hence, interpretations of DTCA are subject to modification by the patient’s chronic illness experience and sociocultural vulnerability to mental illness diagnosis; the chronic and in-flux state of mental illness impose challenges for advertisers wanting to maintain their appeal to audience for extended periods of time. The clinician must accommodate the patient’s shifting perspectives on therapeutic decisions. Interpreting conflicts of therapeutic decision-making with a biopolitics framework appears useful.

5. Case Studies: Analyses of DTCA for insomnia and depression

Discussion in this paper is directed to two instances of commercial advertising – insomnia and depression. Previous studies of DTCA have provided a synchronic study of medical topics through content analysis of DTCA, applying coding schemes of argumentation (Bell et al., 2000; Main et al., 2004; Mohammed & Schulz, 2010). Taxonomies of persuasive appeals include biomedical concepts of effectiveness, social-psychological enhancements, ease of use, and safety, as well as sociocultural concepts of appeal, such as categories of rational, positive, humor, nostalgic, fantasy, sex and negative appeals (Mohammed & Schulz, 2010). The analyses to date have considered the audience of DTCA in terms of the relationship between pharmaceutical drug company and consumer, with the doctor pitched as an intermediary agent (bearing in mind that pharmaceutical appeals direct to health practitioners occur through alternative media, such as academic journals, professional development programs and personal marketing strategies which incorporate gifts, dinner functions and so forth). However, we inquire as to what purpose the DTCA might serve for the clinical practitioner in his/her patient interaction. If DTCA aspires to influence the consumer then it must be sensitive not only to the socio-cultural contexts of illness but also to the diachronic unfolding of controversies associated with patient-centered determination of diagnosis and management of illness in doctor-patient deliberation. Specifically, the call to ‘consult your doctor’ in drug advertisements imposes challenges for the clinician, implying that doctors should not only own the knowledge of remedies but be also sensitive to the controversies associated with medications, the concerns of patients about their drug regimens and the socio-political elements influencing consumer choice. The criticism contrasts appropriate norms of reasoning in a clinical context against the world depicted for patients by advertising.

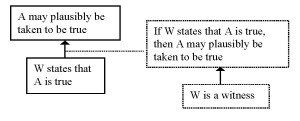

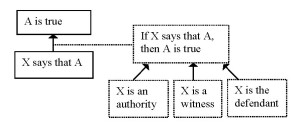

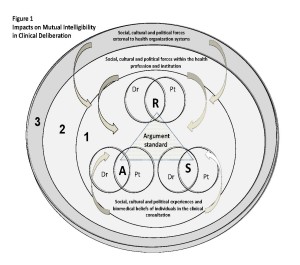

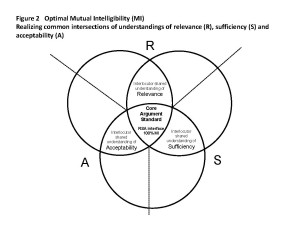

Gilbert and Whyte (2009; forthcoming) assert that if reasons are to be used for building effective and purposeful communication in the clinical context, then the interlocutors must share a common reference of argument standard. Relevant are Johnson and Blair’s (1994, p. 55) RSA criteria for assessing arguments in a clinical communication construct (Gilbert & Whyte, 2009; 2010). Socio-cultural-political experiences as well as biomedical beliefs of the interlocutors influence the notions of relevance, sufficiency and acceptability of evidence that the interlocutors bring to the deliberative dialogue of the clinical encounter. Recognizing zones of difference and realizing intersections of common understanding in what constitutes reasonable argument supports the development of mutual intelligibility in discourse. Lack of mutual intelligibility is a source for potential conflict or misunderstanding.

In the spaces of medical care as envisioned by advertising, doctor and patient standards of sufficiency, relevance and acceptability in DTCA are drawn from the socio-cultural milieu of consumer experience, as drug companies develop strategic appeals to motivate consumer behavior. The DTCA standards challenge the biomedical basis of clinical diagnosis and management and introduce a dynamics to the static model of patient-centeredness, by requiring clinicians to acknowledge the relationship between uncertainty, social milieu and technicality of knowledge in medicine. Thus, we examine appeals of DTCA advertisements in the marketing of Rozerom and Cymbalta in the USA. We adapt the RSA criteria of Johnson and Blair (1994) for the analysis: Standard of sufficiency: The premises of an argument must have the appropriate types and amounts of evidence to support the conclusion. Standard of relevance: The premises of an argument must bear adequate reference to the conclusion. Standard of acceptability: The premises must be acceptable to the audience for the conclusion to be true and hence worthy of the audience’s belief. These criteria challenge the development of a framework of argumentation that encompasses the clinical rationality of providers and the uncertainties, anxieties and insecurities of potential patients – in the span of what are asserted to be publicly informative, non-stigmatizing, soundly-based, helpful advertisements.

5.1. Depression: ‘Cymbalta’ (Depression hurts)

A 2008 ‘Cymbalta’ television commercial constructs a space for ‘taking the first step’, a theme that receives more elaborate articulation on its web site. The commercial is constituted by a voice over, a female announcer speaking with a concerned and reassuring voice about the move from depression to Cymbalta upon obtaining a consultation and prescription with a health care provider. Like many such commercials, a dialogue ensues between the claims narrated within the flow of music and the images of women and men captured by screen shots that play darkness against light across the facial articulation of emotion. The diachronic development moves initially from recognition and definition of a personal issue, naming related mood and body disorders, to a self-recognized condition. “Depression can turn you into a person you don’t recognize, unlike the person you used to be,” the add asserts, voicing over briefly a middle-aged woman with a frown and a black male adult sitting in a dark room while a child with a soccer ball backs out and closes the door. The relevance of the claim is nearly open ended, available to anyone who feels out of sorts with aches and pains. The sufficiency of evidence is unquestioned as victims lost pop up briefly, isolated and alone even in a crowd. As the voice moves from a warning to call a doctor if one thinks of suicidal impulse, to an acknowledgment that thoughts of suicide might be a drug induced effect, the framed examples change to movement with purpose, one smiling woman entering an elevator, another scratching a cat, and a male setting down a sawhorse in his workshop. Meanwhile the conditions of restriction and risks continue to be spoken as the screen unfolds happier people, turning first frowns into soft smiles, with a child with the soccer ball taking his dad out to play. Thus, the standard of acceptability is posed at radical odds, as the spoken message meets criteria of warning while the visual argument dramatizes success. The patient who is encouraged to self-define as depressed and to get help is directed toward a physician who has to sort out a reasonable space for accepting, weighing risks and benefits over time.

We propose that the physician may use the ads to consider strategy for prompting the patient’s illness narrative to move beyond biomedical considerations to the agenda of social participation. However, the physician must not only astutely detect the advertising appeals that are directed to consumers within the design of the advertisement but apply sensitivity in analyzing the impact of those appeals on the individual patient. For, not all advertising techniques of persuasive appeal will impact equally on each and every patient. However, the physician could arguably use the ad imageries to stimulate dialogue that might help to reveal the patient’s concerns of his/her illness within the socio-political context of his/her everyday world. For example, the son-dad imagery might impact more strongly on parents distressed by the impact of their illness on family members and dialogue might subsequently reveal potentially stressful contributors to the perpetuation of depressive illness contained within the patient’s familial relationship mix, which may not be remedied by drugs alone. The ad imageries promote a social ideal that may be far removed from the patient’s social reality. Other issues might be more complex and therefore more difficult to analyze, however, if advertisements lean on socio-political mores to persuade consumer as patient, then there is a duty for the doctor to appreciate these elements impacting on the patient’s resourcefulness in managing their illness. As controversies are addressed, the doctor and patient may each shift their assumptions on what counts as relevant, sufficient and acceptable by considering the arguments posited by each other in dialogue for supporting are challenging the appeals in the ads.

5.2. Insomnia: ‘Rozerem’

The Rozerem commercial addresses what is asserted to be a medical condition in an inventive manner. Interestingly, a frumpy-looking male wanders into his nighttime kitchen and is hailed by Abe Lincoln, reading a newspaper, who gives him the greeting: “Hey, sleeping beauty.” “I didn’t sleep a wink,” the man says and Abe says, “I know,” at which Abe’s beaver chess partner chimes in, “He cheats.” Someone in a space suit floats at the counter throughout. The man attributes his lack of sleep to stress at work and the beaver says that insomnia is common, establishing relevance. The dreamscape recedes and several clips of women up late at night are shown as the narrator voices over those who shouldn’t take the medicine and its risks. The stress condition is not addressed, nor is asserted the established differences with other dependant alternatives. Rather, in the end, Abe the beaver and the spaceman return to counsel, “Just talk to your doctor.” “Because your dreams miss you,” juxtaposes a fantasy world where stress is banished versus a vigilant world where stress-relief requires judgments of hazard and habit. Oddly enough, a figural dream featuring iconic representations of honesty, industry, and exploration sets in motion a myriad of questions that only medical professionals can complete. Whereas the depression commercial minimizes self-esteem of the viewer in relation to the situation, the insomnia commercial maximizes self-esteem – each without bringing into conditions of refined judgment of relevance, the question of sufficient discussion of alternatives, or a coherent narrative of acceptability.

As in the preceding example, this ad proposes opportunities for the physician to identify and explore the patient’s perspectives on his/her illness, and in this instance, the issues of self-esteem and independence in the management of illness being. Ambivalence may be a self-protective mechanism to minimize the acceptance of illness and so divert the stigma associated with diagnosis; hence the ad’s clever way of playing down the potentially underlying causes of insomnia. Instead, insomnia is treated as a rather ordinary problem, a shared experience with the iconic characterization of animals, and certainly not presented as a social stigma to the same extent as depression. The ad suggests that insomnia is a condition readily solved. The persuasive techniques provide a useful means to explore why the patient might be impacted by the ad and stimulate dialogue to reveal interpretations of stress, influences on self-esteem and expectations of therapy (whether chronic or acute), all potential points of controversy in the DTCA. Stimulating dialogue this way might assist the physician to better appreciate the socio-political impacts on the patient’s attitude to illness and so assist the physician to determine an effective communication strategy for therapeutic recommendations.

The two DTCA examples, above, have been considered in a relatively simple analysis to illustrate how biopolitics may be applied to the analysis of controversial elements of DTCA to assist physicians and their patients co-construct interpretations of illness which can be used to inform an effective communication strategy for therapeutic decision-making. More detail on this proposal for analysis will now ensue.

6. Integrating biopolitics into clinical communication

Clinical communication is now recognized as a core clinical skill and models of doctor-patient communication in western medical school curricula promote patient-centered approaches. In the medical literature, notions of personal, professional and institutional discourses have been identified as relevant to the construction of meaning and shared understandings that inform clinical problem-solving and decision-making (Roberts et al., 2000). Challenges to patient-centered approaches are identified in sociolinguistic barriers, institutional cultures of hospital/clinical settings and differences in ethno-medical systems (Diaz-Duque, 2001; Fisher, 2001). However, while the models of clinical communication have expanded to accommodate social contexts of decision-making, there is still a tendency to limit the scope of social inquiry to patient-centeredness elements concerning the patient’s age, gender, socioeconomic status and race (including language background) and the physician’s professional training and experience in the context of the structural features of organized clinical settings (Atkinson, 1995; Clark et al., 1991; McWhinney, 1989; Roberts et al., 2003).

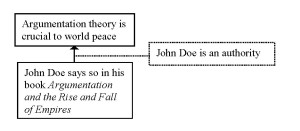

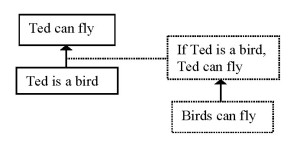

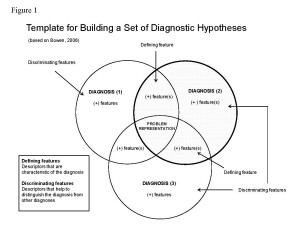

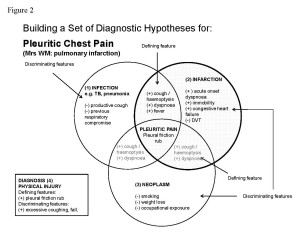

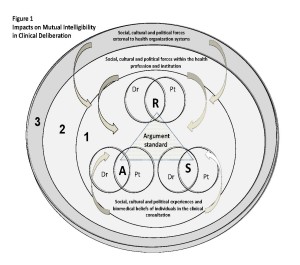

We have considered the controversies in DTCA of mental illness therapies as potential influences on the deliberative dialogue in doctor-patient consultation. We propose a biopolitical dimension to clinical communication frameworks. Figure 1 illustrates a framework for considering the complexities of deliberative dialogue in the clinical consultation.

Figure 1

Diagram 1 is an illustration of the layers of communicative complexity associated with the construction of meaning and decision-making in the dialogue of clinical encounters. Clinical communication experts recognize the essential impact on the doctor-patient relationship of implicit beliefs, understandings and attitudes borne of both the patient’s and doctor’s individual socio-cultural and linguistic experiences. A common set of argument standards is determined by the integration of the socio-cultural values as well as biomedical beliefs of the interlocutors (i.e. the patient and the doctor) in the clinical encounter, which most likely influence argument construction, interpretation and evaluation. Locating common intersections of relevance, acceptability and sufficiency across the patient and doctor’s implicit beliefs, understandings and attitudes generates a common argument standard for effective communication. The RSA triangle at the centre of Figure 1 captures this common intersection in the fundamental communication of the clinical encounter. This is the central zone of clinical deliberation (labeled 1 in Figure 1).

However, one cannot isolate the communication experiences of the doctor-patient relationship to mere artifacts of individual language, culture and experience. For dialogue to be effective, arguments of RSA must also accommodate the contemporary socio-political attitudes of the health profession and institutions which influence the underlying premises of ethical and reasonable clinical practice. This encourages doctors to generate what is referred to as ‘institutional discourse’, a strategy for articulating individual and professional experience within the context of more broadly sanctioned institutional policies and practices (Roberts et al., 2000). Hence, impacting on the fundamental communication between doctor and patient are the sociocultural and political expectations of the medical community for feasible and defensible practice, ensconced in virtues of professionalism. For example, informed consent is a process institutionally sanctioned, bound up with legal and ethical codes of professional conduct, while subject to social and political influences (Goodnight, 2006). This layer of communicative complexity is represented in the second tier of Figure 1 (labeled 2 in Figure 1), exerting a secondary but phenomenally important impact on the RSA standards of argument adhered to by doctor and patient in the clinical encounter.

Clinical communication experts have acknowledged the dimensions of doctor-patient interaction across the two levels of communicative complexity described in the preceding paragraphs, essentially generated within the health professional domains. What we propose is a new ‘tertiary’ dimension to doctor-patient interaction, which predicates the social, cultural and political forces on communication external to health organization systems. This element in our framework is, we believe, missing in current manifestos on clinical communication. In other words, to date, the health professional system has failed to acknowledge the pervasive effect on doctor-patient dialogue of public debate and controversy on human understanding of health, lifestyle and medical condition. DTCA illustrates how socio-cultural perceptions of illness may be construed by advertisers as valuable concepts of remedy and cure within the milieu of fuzzy logic in spaces of public controversy. A bio-political analysis of DTCA provides us with opportunity to examine the possible non-medical motivations of individual beliefs, attitudes and intentions which nevertheless assert sanctions on clinical meanings and interpretations and may therefore ultimately influence decision-making in the dialogue of clinical deliberation. In summary, a biopolitical analysis accessing the three zones of clinical deliberation might yield a more comprehensive strategy for understanding and generating an effective communication strategy in the domain of clinical practice.

Clinicians, we argue, would be wise to appreciate the broader complexities of patient’s decision-making beyond the immediate environment of personal, professional and institutional notions of healthcare, which until now have dominated the definitions and explanations of clinical cultural and communication. Being alert to a broader range of persuasive strategies stimulated by controversies over therapies would seem to enhance a clinician’s knowledge of the patient’s socio-cultural and political reality beyond the mere clinical environment. As controversies over (mental illness) therapies emerge during the juxtaposition of ‘doctor’ versus ‘patient’ explanatory models of illness in clinical dialogue, the astute clinician would seek to understand the biopolitical basis of the patient’s reasoning for either cooperating with or sabotaging options for treatment.

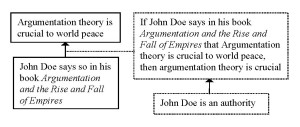

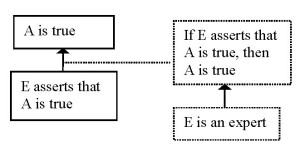

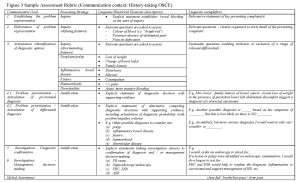

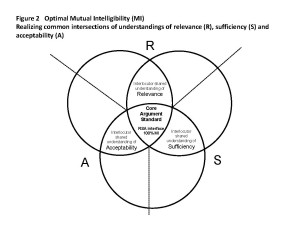

Examining the controversies over therapeutic options using a biopolitical framework may support the clinician adopting a more adaptive and smarter holistic approach to developing mutually agreed explanatory models of illness with his/her patients, conducive for optimizing therapeutic concordance. This essentially requires the interlocutors to reach a mutual understanding on what qualifies as rational evidence in the communicative encounter, which Gilbert and Whyte (2009) define as the mutual intelligibility of argument standard. While acknowledging potential zones of difference, it is the ability of the interlocutors to identify and harness overlap that builds agreement in a communicative encounter. Hence, as controversies over mental illness therapies emerge in the explanatory models of illness posited by the doctor and patient during clinical dialogue, the doctor and patient must negotiate their differences and work towards establishing a common rationality for therapy. This requires each to realize the common intersections of understandings of relevance, sufficiency and acceptability of arguments and to use these to focus the case for therapeutic decision-making. The focus on establishing common elements of relevance, sufficiency and acceptability for optimizing mutual intelligibility within the mileu of fuzzy logic of the clinical encounter is captured in Figure 2. The RSA interface represents the ideal position for concordance on therapeutic decisions, where all criteria of relevance, sufficiency and acceptability in the arguments for therapeutic decision-making are equally agreed upon by the doctor and patient. Outside the core argument standard, RSA standards may be more or less equally distributed, which demands a more deliberative practice of medical consultation to address the asymmetries of doctor-patient interests and reach therapeutic concordance.

Figure 2

7. Conclusion

Drug advertising is part of an ongoing controversy that places pressure on the practices of doctor patient communication. Advertisements directed at mental illness are especially controversial. Argumentation studies should become engaged with how institutions are working strategically to change the boundaries of institutional practices – as such strategic developments alter the availability and nature and duties of reasonable communicative exchange. In the debate over drugs, both sides have a defensible position. Advertisements do perform a public health service; they do indicate ways to name conditions that may be subject to treatment; and, the sales role is qualified by adherence to regulatory policy that makes public statement of risks mandatory and the movement of the industry to support doctor consultation rather than immediate demand for prescription. On the other hand, advertising succeeds by adding to its information a mix of rhetorical appeals, clever arrangement, stylistic emphasis, and aids to memory that render vivid a message. There are no risks to the industry if consumers buy more than necessary or if they pressure doctors for prescriptions. Indeed, the public health rationale becomes a thin justification in the case of mental health where the costs of a disease untreated is figured to be much greater than nearly any rate of over prescription. DTCA may, in fact, be a useful tool for clinical practice.

REFERENCES

Andary, L., Stolk, Y., & Klimidis, S. (2003). Assessing Mental Health Across Cultures. Bowen Hills, Queensland: Australian Academic Press.

Atkinson P. (1995). Medical Talk and Medical Work: The Liturgy of the Clinic. London: Sage Publications.

Bahnji, N. H., Baron D.A., Lacy, B.W., Gross, L.S., Goin, M.K., Sumner, C.R., Fischer, B.A., & Slaby, A.E. (2008). Direct-to-consumer marketing: An attitude survey of psychiatric physicians. Primary Psychiatry, 15(11), 67-71.

Bell, R.A., Kravitz R.L., Wilkes M.S. (1999a). Direct-to-consumer prescription drug advertising and the public. J. Gen Intern Med., 14, 651-657.

Bell, R. A., Kravitz, R. L., & Wilkes. M.S. (1999b). Advertisement-induced prescription drug requests: Patients’ anticipated reactions to a physician who refuses, The Journal of Family Practice, 48(6), 446-452.

Bell, R. A., Kravitz, R. L., & Wilkes, M.S. (1999c). The education value of consumer-targeted prescription drug print advertising, The Journal of Family Practice, 49 (12), 1082-1098.

Bell, R. A., Kravitz, R. L., & Wilkes, M.S. (2000). Direct-to-consumer prescription drug advertising, 1989-1998. A content analysis of conditions, targets, inducements, and appeals. The Journal of Family Practice, 49(4), 329-335.

Berndt, E. R. (2005). To inform or persuade? Direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription drugs. The New England Journal of Medicine, 352(4), 325-329.

Bhanji, N. H. (2008). Direct-to-consumer marketing: An Attitude survey of psychiatric physicians. Primary Psychiatry, 15(11), 67-71.

Bloch, S., & Singh, B.S. (2001). Foundations of Clinical Psychiatry (2nd Ed.). Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

Johnson, R. H., & Blair, J. A. (1994). Logical Self-Defense (3rd Ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Block, A. E. (2007). Costs and benefits of direct-to-consumer advertising: the case of depression. PharmacoEconomics, 511.

Bonaccorso S.N., & Sturchio J.L.(2002). For and against: direct to consumer advertising is medicalising normal human experience: again. British Medical Journal, 324 (7342), 910-911.

Calfee, J. E. (2002). Public policy issues in direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription drugs’, Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 21 (2), 174-193.

Clark, J. A., Potter, D.A., & McKinlay, J.B. (1991). Bringing social structure back into clinical decision making. Soc. Sci Med., 32(8), 8 853-866.

Coney, S (2002). Direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription pharmaceuticals: A consumer perspective from New Zealand. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing 22(2), 213-223.

Cymbalta, Depression hurts. Youtube, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kX-RryzCG8E. Accessed July 30, 2010.

Dartnell, J.G.A., (2001). Understanding, Influencing and Evaluating Drug Use. Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Limited.

Dinglestad, D., R. Gosden, B. M., and Vakas, N. (1996). The social construction of drug debates. Social Science and Medicine, 43(12), 1829-1838.

Direct to Consumer Advertising (DTCA) of Prescription Medicines and the Quality Use of Medicines (QUM). 2004. Accessed June 2010 at:www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content

Donohue, J., & Berndt, E. (2004). Effects of direct-to-consumer advertising on medication choice: The case of antidepressants. Journal of Public Pol Marketing 23, 115-127.

Fisher, S. (2001). Doctor talk/Patient talk: How treatment decisions are negotiated in doctor-patient communication. In D.D. Oaks (Ed.), Linguistics at Work: A Reader of Applications (pp. 99-121), Cambridge, MA: Heinle & Heinle.

Gellad, Z.F., & Lyles, K.W. (2007). Direct-to consumer advertising of pharmaceuticals. Am J. Med 2007, 120(6) 475-480.

Gilbert, K. and Whyte, G. (2009). Argument and medicine: A model of reasoning for clinical practice. In J. Ritola (Ed.), Argument Cultures. Conference proceedings of the 8th Ontario Society for the Study of Argumentation (OSSA) Conference [CD]. University of Windsor: OSSA.

Gilbert, K., & Whyte, G. (forthcoming). The use of arguments in medicine: A model of reasoning for enhancing clinical communication. (revised version of OSSA2009 paper). Monash University Linguistics Papers (MULP).

Gilbody, S., Wilson, P., & Watt, I. (2005). Benefits and harms of direct to consumer advertising: a systematic review. Quaterly Sat Health Care 2005, 14(4), 246-250.

Goldman, R., & Montagne, M. (1986). Marketing ‘mind mechanics’: decoding antidepressant drug advertisements. Social Science and Medicine, 22, 1047-1058.

Goodnight, G.T. (2006). When reasons matter most: pragma-dialectics and the problem of informed consent. In P. Houtlosser & A. van Rees (Eds.), Considering pragma-dialectics (pp. 75-85), Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Goodnight, G. T. (2008). Strategic maneuvering in direct to consumer drug advertising: a study in argumentation theory and new institutional theory. Argumentation, 22, 359-371

Hoffman, JR, & Wilkes, M. (1999). Direct to consumer advertising of prescription drugs. British Medical Journal, 318(7194), 1301-1302.

Holmer, A. F. (1999). Direct-to-consumer prescription drug advertising builds bridges between patients and physicians. JAMA, 281(4), 380-382

Kravitz, R.L, Epstein, R.M., Feldman, M.D., Franz, C.E., & Azari R., et al. (2005). Influence of patients’ requests for direct-to-consumer advertised antidepressants: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 293, 1995-2002.

Lacasse, J. R. (2005). Consumer advertising of psychiatric medications biases the public against nonpharmacological treatment. Ethical Human Psychology and Psychiatry, 7(3), 175-179.

Lacasse, J. R., & Jonathan, L. (2005). Serotonin and Depression: A disconnect between the advertisements and the scientific literature. PLoS Med, 2(12): e392.doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020392

Lion, J., B. Regan, R. Taylor et al. (1979). Psychiatrists’ opinions of psychotropic drug advertisements. Social Science and Medicine, 13A, 123-125.

Lovdahl, U., Riska, A., & E. Riska, E. (1999). Gender display in Scandinavian and American advertising for antidepressants. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 27, 306-310.

MacKenzie FJ, Jordens, C.F., & Ankeny, R.A., et al. (2007). Direct-to-consumer advertising under the radar: the need for realistic drugs policy in Australia. Intern Med J., 37(4), 224-228.

Main K.J., Argo J.J., & Huhmann B. (2004). Pharmaceutical advertising in the USA: Information or influence? International Journal of Advertising, 23, 119-142.

McWhinney, I. (1989). The need for transformed clinical method. In M. Stewart & D. Roter (Eds.), Communicating with Medical Patients. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Mintzes, B. (2002). For and against: Direct to consumer advertising is medicalising normal human experience. British Medical Journal, 324, 908-909.

Mohammed, D., & Schulz, P. (2010). Argumentative insights for the analysis of direct-to-consumer advertising. Paper presented at the 7th International Conference on Argumentation, Amsterdam, June 29-July 2, 2010.

Owen, J. (1992). Images used to sell psychotropic drugs. Psychiatric Bulletin, 16, 25-26.

Park, J. S., & Grow, J. M. (2008). The social reality of depression: DTC advertising of antidepressants and perception of the prevalence and lifetime risk of depression. Journal of Business Ethics, 79, 379-393.

PhRMA, Principles and Guidelines. Direct to Consumer Advertising. Available at: 222.phrma.org/principles_and_guidelines/.

Quinn, J. Nangle, M., & Casey, P.R. (1997). Analysis of psychotropic drug advertising. Psychiatric Bulletin, 21, 597-599.

Riska, E., & Hagglund, U. (1991). Advertising for psychotropic drugs in the Nordic countries: metaphors, gender and life situations. Social Science and Medicine, 32, 465-471.

Rozerem Commercial, Your dreams miss you. You Tube. Accessed July 30, 2010.

http://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=Roserem+commercial&aq=f

Roberts C., Sarangi, S., Southgate, L., Wakeford, R., & Wass, V. (2000). Oral examinations – equal opportunities, ethnicity, and fairness in the MRCGP. British Medical Journal, 320(7231), 370-74.

Robinson, A.R., Hohmann, K. B., & Rifkin, J.L. et al. (2004). Direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical advertising: physician and public opinion and potential effects on the physician-patient relationship. Arch Intern Med., 164(4) 427-432.

Rosenthal M.B., Berndt, E.R., Donohue, J.M., Frank, R. G, & Epstein, A.M. (2002). Promotion of prescription drugs to consumers. New England Journal of. Medicine, 246, 498-505.

Seidenberg, R. (1971). Drug advertising and perception of mental illness. Mental Hygiene, 55, 21-31.

Sue, S., & Zane, N. (1987). The role of culture and cultural techniques in psychotherapy: A critique and reformulation. American Psychologist, 42, 37-45.

Sweet, M. (n.d.). Pharmaceutical marketing and the Internet. Australian Prescriber

www.australianprescriber.com/magazine/32/1/2/4/

Troop, L., & Richards, D. (2003). New Zealand deserves better. Direct-to-consumer advertising (DTCA) of prescription in New Zealand: for health or for profit? The New Zealand Medical Journal, 116(1180).

Vitry, A. (2007). Is Australia free from direct-to-consumer advertising? Australian Prescriber.

Wolfe, S.M. (2002). Direct-to-consumer advertising: Education or emotion promotion. New England Journal of Medicine, 346(7), 524-526.

1. Introduction

1. Introduction