ISSA Proceedings 2010 – A Formal Model Of Legal Proofs Standard And Burdens

This paper presents a formal model that enables us to define five distinct types of burden of proof in legal argumentation. Four standards of proof are shown to play a vital role in defining each type of burden. These standards of proof are defined in a precise way suitable for computing in argumentation studies generally, but are based on a long tradition of their use in law. The paper presents a computational model based on these notions that represents a dialectical process that goes from initial claims where issues to be decided are set, and produces a justification for arriving at a decision for one side or the other that can withstand a critical evaluation by a particular audience. The role of the audience can be played by the respondent in some instances, or by a neutral third party audience, depending on the type of dialogue. The paper builds on previous work (Gordon, Prakken and Walton, 2007; Gordon and Walton, 2009) that has applied the Carneades model to studying burden of proof in legal argumentation.

This paper presents a formal model that enables us to define five distinct types of burden of proof in legal argumentation. Four standards of proof are shown to play a vital role in defining each type of burden. These standards of proof are defined in a precise way suitable for computing in argumentation studies generally, but are based on a long tradition of their use in law. The paper presents a computational model based on these notions that represents a dialectical process that goes from initial claims where issues to be decided are set, and produces a justification for arriving at a decision for one side or the other that can withstand a critical evaluation by a particular audience. The role of the audience can be played by the respondent in some instances, or by a neutral third party audience, depending on the type of dialogue. The paper builds on previous work (Gordon, Prakken and Walton, 2007; Gordon and Walton, 2009) that has applied the Carneades model to studying burden of proof in legal argumentation.

1. Some Features of Previous Work

This survey is very brief, but fuller accounts can be found in Gordon and Walton, 2009, pp. 250-256). Gordon (1995) modeled legal argumentation as a dialectical process with several stages. Freeman and Farley (1995) presented a computational model of burden of proof as a part of a dialectical process that moves ahead to a conclusion under conditions where knowledge is incomplete and uncertain. In their model standards of proof are defined that represent a level of support that must be achieved by one side to win an argument. Burden of proof is seen as acting both as a move filter in a dialogue, and as a dialogue termination criterion that determines the eventual winner of the dialogue. Prakken and Sartor (2006) constructed an argumentation-based formal model of defeasible logic called the litigation inference system that separated three different types of burden of proof in legal argumentation called the burden of persuasion, the burden of production and the tactical burden of proof. Prakken and Sartor (2009, p. 228) described these three burdens as follows. The burden of persuasion specifies which party has to prove some proposition for it to win the case, and also specifies what proof standard has to be met. The burden of persuasion remains the same throughout the trial, once it has been set. Both the burden of persuasion and the burden of production are assigned by law. The burden of production is the provision of sufficient evidence to consider the case. The tactical burden of proof is determined by the advocate on one side who must judge the risk of ultimately losing on the particular issue being discussed at that point if he fails to put forward further evidence concerning that issue.

The introduction of an audience in formal models dialectical argumentation, based on the work by Perelman and Olbrects-Tyteca (1969), has now been carried forward in recent computational models. It is a feature of the formal system of value-based argumentation frameworks (Bench-Capon, 2003) that in practical reasoning, or reasoning about what should be done in a particular situation, the acceptability of an argument should depend in part on the values of the audience to whom the argument is addressed. Bench-Capon, Doutre and Dunne (2007) offer formal dialogue systems that allow for prioritization of the values of the audience to be used as part of the process for evaluating the argument. They build a system of formal dialogues for carrying out evaluation of arguments in this manner, and give soundness and completeness results for the dialogue systems. This idea of incorporating the audience into the dialogue structure for arguing with burden of proof is an important part of the model presented in this paper.

2. Burdens and Standards of Proof in Legal Settings

Burdens and standards of proof are used in many different contexts of legal procedures to determine how strong an argument needs to be to meet a standard appropriate for its use in that setting. A simplified description of the sequence of argumentation in a typical civil procedure, roughly based on the law in California, can give the reader some idea of such a sequence of argumentation. At the first stage, a civil case begins by one party, called the plaintiff, filing a complaint that makes a claim against the other party, called the defendant. In addition to the claim itself, the complaint contains assertions about the facts of the case that the plaintiff contends are true and that are sufficient to prove that the defendant has breached some obligation and entitling the plaintiff to compensation. At the next stage the defendant can choose from several options for making a response. One of these is to file an answer in which the allegations are conceded or denied. The answer may also contain additional facts called an affirmative defense that contains counterarguments to the arguments previously put forward by the plaintiff. At the next step, the plaintiff can reply by conceding or denying these additional facts in the defendant’s previous move. The next stage is a process of discovering evidence, which may take place for example by the interviewing of witnesses and the recording of their testimony. The next stage is the trial where the evidence already collected is presented to the trier, a judge or possibly also a jury, and further evidence is introduced, for example by the examination of witnesses in court. At the closing stage of the trial the judge makes a decision based on the whole body of evidence brought forward during the trial, or if there is a jury the judge instructs the jury about the law applicable to the case. The jury then has the duty of deciding what the facts of the case are, and making a verdict based on those facts. As part of the closing stage, the judge enters a judgment as a verdict, which may then be later appealed if there are grounds for an appeal.

To describe how the chain of argumentation goes forward through the different stages of the sequence of dialogue, it is important to distinguish between different kinds of burden of proof at different states. The first can be called the burden of claiming. When a person makes a claim at the first point in the sequence described above, he has a right to a legal remedy if he can bring forward facts that are sufficient to prove that he is entitled to some remedy. The second type of burden of proof is the burden of questioning, or it could be called the burden of contesting. If one party makes an allegation by claiming that some proposition is true during the process of the argumentation, and the other party fails to present a counterargument, or even to deny the claim, then that claim is taken to be implicitly conceded. This type of burden of proof is called the burden of questioning because it puts an obligation on the other party to question or contest a claim made by the other side, by asking the other side to produce arguments to support its claim. This brings us to the third burden, called the burden of production in law, or sometimes burden of producing evidence. This is the burden to respond to a questioning of one’s claim by producing evidence to support it. We are already familiar with this kind of burden of proof as it is the one typically associated with burden of proof in philosophy. This is the burden to support a claim by arguments when this claim is challenged by the other party in the dialogue. The fourth type of burden of proof is called the burden of persuasion in law. It is set by law at the opening stage of the trial, and determines which side has won or lost the case at the end of the trial once all the arguments have been examined. The burden of persuasion works differently in a civil proceeding than in a criminal one. In a civil proceeding, the plaintiff has the burden of persuasion for all the claims he has made as factual, while the defendant has the burden for any exceptions that he has pleaded. In criminal law the prosecution has the burden of persuasion for all facts of the case. These include not only the elements of the alleged crime, but also the burden of disproving defenses. For example, in a murder case in California, the prosecution has to prove that there was a killing, and that it was done with malice aforethought. But if the defendant pleads self-defense, the prosecution has to prove that there was no self-defense. This is an important point, for it shows that this fourth type of burden of proof varies with the context, that is, with the type of trial. The fifth type of burden of proof is called the tactical burden of proof. It applies during the sequence of argumentation during the trial, when a lawyer pleading a case has to make strategic decisions on whether it is better to present an argument or not. To make such a judgment, the advocate on each side needs to sum up and evaluate the whole network of previous arguments, both on its own side and the other side, and then use this assessment to determine whether the burden of persuasion is met at that point or not. This is a hypothetical assessment made only by the advocates on the two sides, and the judge and jury have no role in it. The tactical burden of proof is the one that is properly set to shift back and forth during a sequence of argumentation.

The question of when a burden of proof is met by a sequence of argumentation in a given case depends on the proof standard that is required for a successful argument in that case. Law has several proof standards of this kind of which we will briefly mention only four. The law defines the standards using cognitive terminology, for example proposing assessment of whether an attempt at proof is credible or convincing to the mind examining it. However, these cognitive descriptions, although they are useful in law for a judge to instruct the jury on what the burden of proof is in the case, are not precise enough to serve the purposes of argumentation theory generally, or for attempts to provide argumentation models in computing. According to the scintilla of evidence standard, an argument is taken to be a proof even if there is only a small amount of evidence in the case that supports the claim at issue. The preponderance of evidence proof standard is met by an argument that is stronger than its matching counterargument in the case, even if it is only slightly stronger. In other words, when the argumentation on both sides is in at the closing stage, if the argumentation on the one side to support its ultimate claim to be proved is stronger than that of the other side, then the first side wins. The clear and convincing evidence standard is higher than that of the preponderance standard, but not as high as the highest standard, called proof beyond reasonable doubt. The beyond reasonable doubt standard is the strongest one, and it is applicable in criminal cases.

There seem to be two options with respect to defining the standards. One is to define them in the cognitive terms familiar in the kinds of definitions given in Black’s Law Dictionary for example, in its various editions. The other is the attempt to make the definitions precise by proposing numerical values representing degrees of belief or probability, that attach to each claim to be proved. For example, preponderance of the evidence could be represented by a probability value of .51, while beyond reasonable doubt could be represented by a higher probability value of .81. Although attempts of this sort have been made from time to time, we do not think that this is a useful approach generally. We will propose a third way. This third way will respect the three principles of any formal account of argument accrual formulated by Prakken (2005). The first principal is that combining several arguments together can not only strengthen one’s position but also weaken it. The second principle is that when several arguments have been accrued, the individual arguments, considered separately, should have no impact on the acceptability of the proposition at issue. The third principle is that any argument that is flawed may not take part in the aggregation process.

3. Argument and Dialogue Structures

In Gordon and Walton (2009, pp. 242-250) we presented a simple abstract formal model designed to capture the distinctions between the various types of burden of proof. Here we summarize the elements of the formal model that define the standards and burdens of proof. The formal model assumes that we have different types of dialogue that can be defined, sets of argumentation schemes with critical questions, as well as rules and commitment stores for each type of dialogue. In presenting these definitions we abstract from all these other components, to produce the simplest model that enables us to distinguish between different kinds of proof standards and burdens of proof that are important to know about. We begin with a definition of the notion of an argument suitable for our purposes representing the premises of an argument, the distinction between types of premises, and the conclusion of the argument. In this model, the proponent of an argument has the burden of production for the ordinary premises, while the respondent has the burden of production for exceptions.

Let L be a propositional language. An argument is a tuple 〈P,E,c〉 where P ⊂ L are its premises, E ⊂ L are its exceptions and c ∈ L is its conclusion. For simplicity, c and all members of P and E must be literals, i.e. either an atomic proposition or a negated atomic proposition. Let p be a literal. If p is c, then the argument is an argument pro p. If p is the complement of c, the argument is an argument con p.

Conclusions can be generated from premises using the inference rules of classical logic and argumentation schemes. This definition of the concept of argument does not represent a fully developed argumentation theory. It merely contains enough structure to enable us to model the distinction between the various kinds of burden of proof. But we need one other thing to accomplish this purpose. We also have to model argumentation as a process that goes through several stages. Hence we introduce the notion of a dialogue that has three stages, an opening stage, an argumentation stage and a closing stage. This notion of dialogue that is suitable for our purposes is defined as follows.

A dialogue is a tuple 〈O,A,C〉, where O, A and C, the opening, argumentation, and closing stages of the dialogue, respectively, are each sequences of states. A state is a tuple 〈arguments,status〉, where arguments is a set of arguments and status is a function mapping literals to their dialectical status in the state, where the status is a member of {claimed, questioned}. In every chain of arguments, a1,…an, constructable from arguments by linking the conclusion of an argument to a premise or exception of another argument, a conclusion of an argument ai may not be a premise or an exception of an argument aj, if j<i. A set of arguments which violates this condition is said to contain a cycle and a set of arguments which complies with this condition is called cycle-free.

For our purposes, the opening and confrontation stages of the dialogue as defined by van Eemeren and Grootendorst (2004) are both included as parts of the opening stage. We also draw a distinction between a stage of argumentation and a state of argumentation. Each dialogue is divided into its three stages, according to the definition above. The status function of a state maps literals to their dialectical status in that state, where the status can be either that of being claimed or being questioned. We disallow the construction of chains of arguments that contain a cycle. This definition has implications for the modeling of circular argumentation and the fallacy of begging the question, but there is no space to discuss these implications here. Confining the arguments of a stage to those that are cycle free is meant to simplify the model at this point.

The next concept we need to define is that of an audience that is able to assess the acceptability of propositions. We draw upon the recent literature on value-based argumentation frameworks (Bench-Capon, 2003) where arguments are evaluated by an audience. In law the role of audience is taken by a trier of fact, which could be a judge or jury in a legal trial.

An audience is a structure 〈assumptions,weight〉, where assumptions ⊂ L is a consistent set of literals assumed to be acceptable by the audience and weight is a partial function mapping arguments to real numbers in the range 0.0…1.0, representing the relative weights assigned by the audience to the arguments.

There are different methods an audience can use to evaluate arguments. In value-based argumentation frameworks, the audience uses a partial order on a set of values (Bench-Capon et al., 2007). In our system a numerical assignment is used to order arguments by their relative strength for a particular audience.

The next concept we need to define is that of an argument evaluation structure. It brings together the three concepts of state, audience and standard, providing the general framework necessary to evaluate an argument.

An argument evaluation structure is a tuple 〈state, audience, standard〉, where state is a state in a dialogue, audience is an audience and standard is a total function mapping propositions in L to their applicable proof standards in the dialogue. A proof standard is a function mapping tuples of the form 〈issue, state, audience〉 to the Boolean values true and false, where issue is a proposition in L, state is a state and audience is an audience.

We can now define notion of the acceptability of a proposition.

A literal p is acceptable in an argument evaluation structure 〈state, audience, standard〉 if and only if standard(p) (p, state, audience) is true.

Basically what this definition stipulates is that a proposition in an argument evaluation structure is acceptable if and only if it meets its standard of proof when put forward at a particular state according to the evaluation placed on it by the audience.

Next we define the various proof standards that are used to evaluate arguments. All of these proof standards need to make use of the prior concept of argument applicability, as defined below. In this definition, P is the set of premises of an argument, E is the set of exceptions, and c is the conclusion of the argument.

Applicability of Arguments. Let 〈state, audience, standard〉 be an argument evaluation structure. An argument 〈P,E,c〉 is applicable in this argument evaluation structure if and only if:

1. the argument is a member of the arguments of the state,

2. every proposition p ∈ P, the premises, is an assumption of the audience or, if neither p nor the complement of p is an assumption, is acceptable in the argument evaluation structure and

3. no proposition p ∈ E, the exceptions, is an assumption of the audience or, if neither p nor the complement of p is an assumption, is acceptable in the argument evaluation structure.

This definition has three requirements. The first is that the argument is within the state being considered. The second is the every premise has to either be an assumption of the audience, or if neither it nor its complement is an assumption, it has to be acceptable in the argument evaluation structure. The third is that no exception is an assumption of the audience, or if neither it nor its complement is an assumption, is acceptable in the argument evaluation structure.

4. Proof Standards

Now we are ready to define the various standards of proof. The weakest of the proof standards, called the scintilla of evidence standard, is defined as follows.

Scintilla of Evidence Proof Standard. Let 〈state, audience, standard〉 be an argument evaluation structure and let p be a literal in L. scintilla{ (p, state, audience) = true} if and only if there is at least one applicable argument pro p in state.

A proposition meets this standard if it is supported by at least one applicable pro argument. Both the proposition and its negation can be acceptable in an argument evaluation structure when this standard is being applied. However, this is the own only standard according to which both the proposition and its negation can be acceptable.

The next standard to be defined, one of the three most important proof standards in law, is that of the preponderance of the evidence, the standard applied in civil cases.

Preponderance of Evidence Proof Standard. Let 〈state, audience, standard〉 be an argument evaluation structure and let p be a literal in L. preponderance(p, state, audience) = true if and only if

1. there is at least one applicable argument pro p in stage and

2. the maximum weight assigned by the audience to the applicable arguments pro p is greater than the maximum weight of the applicable arguments con p.

The preponderance of evidence standard is satisfied if the maximum weight of the applicable pro argument outweighs the maximum weight of the applicable con arguments, by even a small amount of evidential weight.

According to the next standard, that of clear and convincing evidence, in addition to the conditions of the preponderance of evidence standard, the maximum weight of the pro arguments must exceed a threshold and the difference between the maximum weight of the pro arguments and the maximum weight of the con arguments must exceed another threshold.

Clear and Convincing Evidence Proof Standard. Let 〈state, audience, standard〉 be an argument evaluation structure and let p be a literal in L. clear–and–convincing (p, state, audience) = true if and only if

1. the preponderance of the evidence standard is met,

2. the maximum weight of the applicable pro arguments exceeds some threshold α, and

3. the difference between the maximum weight of the applicable pro arguments and the maximum weight of the applicable con arguments exceeds some threshold β.

It is easy to see that the clear and convincing evidence is only satisfied by an argument that has greater weight than that required to meet the preponderance standard. It has to exceed the threshold as well as meeting the preponderance standard. In the model we do not set any specific threshold. The beyond a reasonable doubt standard is defined in a comparable way to the clear and convincing evidence standard, except that the maximum weight of the con arguments must be below the threshold of reasonable doubt.

Beyond reasonable doubt proof standard. Let 〈state, audience, standard〉 be an argument evaluation structure 〈state, audience, standard〉 and let p be a literal in L. beyond–reasonable–doubt (p, state, audience) = true if and only if

1. the clear and convincing evidence standard is met and

2. the maximum weight of the applicable con arguments is less than some threshold γ.

We have not given precise numerical definitions of the thresholds, because these need to be set by the dialogue rules applicable to a particular case.

5. Accrual in Argument Evaluation

We do not use summing up the weights of the applicable pro and con arguments as part of our system of argument evaluation, because arguments cannot be assumed to be independent. Also, in our view proof standards cannot and should not be interpreted probabilistically. The first and most important reason is that probability theory is applicable only if statistical knowledge about prior and conditional probabilities is available. Presuming the existence of such statistical information would defeat the whole purpose of argumentation about factual issues, which is to provide methods for making justified decisions when knowledge of the domain is lacking. Another argument against interpreting proof standards probabilistically is more technical. Arguments for and against some proposition are rarely independent. What is needed is some way to accrue arguments which does not depend on the assumption that the arguments or evidence are independent. Thus the question is how to approach argument accrual.

We have to leave it to the audience to judge the effects of interdependencies among the premises on the weight of an argument. However, our model satisfies all three of Prakken’s (2005) principles of accrual. As a reminder we repeat these here. The first one is that combining several arguments together can not only strengthen one’s position but also weaken it. The second principle is that when several arguments have been accrued, the individual arguments, considered separately, should have no impact on the acceptability of the proposition at issue. The third principle is that any argument that is flawed may not take part in the aggregation process. Prakken explains the first principle as follows. The principle that accruals are sometimes weaker than their elements is illustrated by a jogging example (Prakken, 2005, p. 86). In this example, there are two reasons not to go jogging. One is that it is hot and the other is that it is raining. But suppose we accrue these two reasons, producing a combination of reasons for not going jogging. Does the accrual make the argument even stronger? Not necessarily, because for a particular jogger, the heat and the rain may offset each other, so that the original argument becomes weaker. It may even be the case that for another jogger the combination of heat and rain may be very pleasant. In this instance, the accrued argument may even present a positive reason to go jogging.

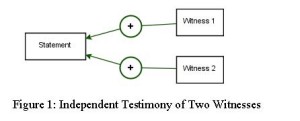

Another example Prakken (2005, p. 86) gives is that of two witnesses who make the same statement. We can represent this situation as shown in Figure 1, with two separate arguments for the conclusion that the statement is true.

What Figure 1 shows is a convergent argument, each of which has one premise. Witness testimony is fallible as a form of argumentation, and therefore neither argument is conclusive by itself. Let’s say that the standard is that of the preponderance of the evidence, and for the sake of the example we assign each argument a probative weight of .5. Let’s say that the testimony of one witness agrees with the testimony of the other. In such a case, normally if we were to accrue the two arguments together and combine them into a single argument, because of the agreement testimony of the witnesses, the probative weight supplied by the combined arguments would be greater than .5.

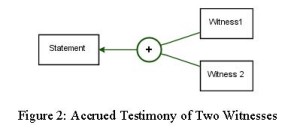

However, Prakken (p. 86) asks us to make the following additional supposition: “if the witnesses are from a group of people who are more likely to confirm each other statements when these statements are false than when they are true, the accrual will be weaker than the accruing reasons”. This situation is represented in Figure 2.

In Figure 2 we now have a linked argument, a single argument with two premises. Accrual has now taken place, and the original pair of argument shown in Figure 1 has been combined into a single argument.

What happens now is that since we know that the two witnesses are from a group of people who are more likely to confirm each other statements when these statements are false than when they are true, the probative weight both premises supply when combined into a single argument is less than it was before. In Figure 2, we have assigned a probative weight of less than .5 to the argument representing the accrued testimony of the two witnesses.

6. Burdens of Proof Defined

The issue to be discussed in persuasion dialogue is set at the opening phase. When arguments are put forward on both sides during the argumentation stage, they are judged to be relevant or not in relation to the issue set in the opening phase. The burdens of claiming and questioning apply during the opening stage. The burden of production and the tactical burden of proof apply during the argumentation stage. The burden of persuasion is set at the opening stage, but is applied at the closing stage, where it determines which side has won the case and which side has lost. The burden of proof is also used hypothetically by each party during the argumentation stage to estimate its tactical burden of proof.

During the opening stage, where the burdens of claiming and questioning apply, a proposition claimed is taken to be conceded unless it is questioned by the other party. Because it is taken to be conceded, it requires the audience to assume that it is true. The burdens of claiming and questioning are defined as follows.

Burdens of Claiming and Questioning. Let s1,…,sn be the states of the opening stage of a dialogue. Let 〈argumentsn, status〉 be the last state, sn, of the opening stage. A party has met the burden of claiming a proposition p if and only if statusn(p) ∈ {claimed, questioned}, that is, if and only if statusn(p) is defined. The burden of questioning a proposition p has been met if and only if statusn(p) = questioned.

Only propositions that have been claimed at an earlier state of the argumentation sequence can be questioned. Therefore a questioned proposition satisfies the burden of claiming. This way of formulating the model gives only minimal requirements for raising issues in the opening stage. Rules for a specific type of dialogue can state additional requirements. For example in law, in order to make a claim the plaintiff must accompany it with facts that are sufficient to give the plaintiff a right to judicial relief.

The burden of production comes into play only during the argumentation stage of a dialogue. The proponent who puts forward an argument has the burden of production for its premises, and this burden can be satisfied according to the proof standard of scintilla of evidence. The respondent has the burden of production for an exception. The burden of production is defined as follows.

Burden of Production. Let s1,…,sn be the states of the argumentation stage of a dialogue. Let 〈argumentsn, statusn〉 be the last state, sn, of the argumentation phase. Let audience be the relevant audience for assessing the burden of production, depending on the protocol of the dialogue. Let AES be the argument evaluation structure 〈sn, audience, standard〉, where standard is a function mapping every proposition to the scintilla of evidence proof standard. The burden of production for a proposition p has been met if and only if p is acceptable in AES.

An objection to this way of defining the burden of production would be that since scintilla of evidence is the weakest proof standard, using it to test whether the burden of production has been met is too weak. It might seem that any arbitrary argument, even one that is worthless would be sufficient to fulfill the burden of production. However, there are resources in place to ensure that this does not happen. For one thing, such a worthless argument can be defeated by critical questioning, or by attacking its premises. During the argumentation stage, implicit premises underlying the argument can be brought out by critical questioning and attacked. We can see then that the burden of production for an argument might be met at some state during the argumentation stage, but then fail to be met at some later state where the argument has been attacked or questioned.

The burden of persuasion has been met by one side at the closing stage if the proposition at issue that is supposed to be proved by that side is acceptable to the audience. The burden of persuasion for a trial is set by law, and therefore it is assigned by the judge who has to instruct the jury about it, if there is a jury. The standard of proof for a criminal trial is that of beyond reasonable doubt, whereas the standard of proof for a civil trial is that of preponderance of the evidence. The burden of persuasion is defined as follows.

Burden of Persuasion. Let s1,…,sn be the states of the closing stages of a dialogue. Let 〈argumentsn, statusn〉 be the last state, sn, of the closing stage. Let audience be the relevant audience for assessing the burden of persuasion, depending on the dialogue type and its protocol. Let AES be the argument evaluation structure 〈sn, audience, standard〉, where standard is a function mapping every proposition to its applicable proof standard for this type of dialogue. The burden of persuasion for a proposition p has been met if and only if p is acceptable in AES.

How the burdens of persuasion and production work in a criminal trial is worth noting briefly here. The prosecution has the burden of persuasion to prove its claim set at the opening stage. The defendant has the burden of production for exceptions. For example, in a murder trial the defendant has the burden of production for self-defense. However, in a criminal trial, once this burden has been met by the defendant, the prosecution has the burden of persuading the trier of fact, beyond a reasonable doubt, that the defendant did not act in self-defense. Our model represents this situation is by making the exception and ordinary premise after the burden of production has been met.

The tactical burden of proof, which applies only during the argumentation stage, is the only burden that can shift back and forth between the two parties. To meet the requirements for tactical burden of proof, an arguer needs to consider whether stronger arguments might be needed to persuade the audience. This assessment depends on whether the audience reveals its evaluations to the parties on each side as the argumentation stage proceeds. In a trial, however, this does not happen.

Tactical Burden of Proof. Let s1,…,sn be the states of the argumentation phase of a dialogue. Assume audience is the audience which will assess the burden of persuasion in the closing phase. Assume standard is the function which will be used in the closing stage to assign a proof standard to each proposition. For each state si in s1,…,sn, let AESi be the argument evaluation structure 〈si, audience, standard〉. The tactical burden of proof for a proposition p is met at state si if and only if p is acceptable in AESi.

The tactical burden of proof comes into play when a proponent has an interest in proving some proposition that is not acceptable to the respondent at that state, given the argumentation that has gone forward so far. In a real example, evaluation of the tactical burden of proof would depend on how relevance is modeled in the type of dialogue.

7. Conclusions

In this paper we presented formal structures to represent argumentation in dialogues, and incorporated the notion of audience into the formal structure. We argued that whether a burden of proof is met by a sequence of argumentation in a given case depends on the proof standard that is required for a successful argument in that case. We defined four such proof standards, scintilla of evidence, preponderance of evidence, clear and convincing evidence, and finally, beyond reasonable doubt. We used the model and standards to distinguish five types of burden of proof: burden of claiming, burden of questioning, burden of production, burden of persuasion and tactical burden of proof.

REFERENCES

Bench-Capon, T. (2003). Persuasion in Practical Argument Using Value-Based Argumentation Frameworks. Journal of Logic and Computation, 13(3), 429-448.

Bench-Capon, T. J. M., Doutre, S., & Dunne, P. E. (2007). Audiences in Argumentation Frameworks. Artificial Intelligence, 171(42-71).

Eemeren, F. H. van, & Grootendorst, R. (2004). A systematic theory of argumentation: The pragma-dialectical approach. Cambridge University Press.

Freeman, K., & Farley, A. M. (1996). A Model of Argumentation and Its Application to Legal Reasoning. Artificial Intelligence and Law, 4(3-4), 163-197.

Gordon, T. F. (1995). The Pleadings Game; An Artificial Intelligence Model of Procedural Justice. Dordrecht; Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Gordon, T. F., Prakken, H., & Walton, D. (2007). The Carneades Model of Argument and Burden of Proof. Artificial Intelligence, 171(10-11), 875-896.

Gordon, T. F., & Walton, D. (2009). Proof Burdens and Standards. In I. Rahwan & G. Simari (Eds.), Argumentation in Artificial Intelligence (pp. 239-260). Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag.

Perelman, C., & Olbrechts-Tyteca, L. (1969). The New Rhetoric. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

Prakken, H. (2005). A Study of Accrual of Arguments, with Applications to Evidential Reasoning. Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Law (pp. 85-94). New York: ACM Press.

Prakken, H., & Sartor, G. (2009). A Logical Analysis of Burdens of Proof. In H. Kaptein, H. Prakken, & B. Verheij (Eds.), Legal Evidence and Proof: Statistics, Stories, Logic (pp. 223-253). Farnham: Ashgate Publishing.