ISSA Proceedings 2010 – Iconicity In Visual And Verbal Argumentation

1. Functional equivalency

1. Functional equivalency

Imagine a drawing of a boat that clearly resembles the Titanic, but its bow has the shape of Bill Clinton’s face. The bow has just hit an iceberg. The iceberg is now sinking. It is not difficult to imagine this drawing as a cartoon. Does this cartoon represent argumentation?

Answering this question requires an argumentative reconstruction. Just as it requires an argumentative reconstruction to determine whether the verbal text “If Clinton were the Titanic, the iceberg would sink” represents argumentation. It was actually this verbal text that circulated in Washington during February 1998 (Fauconnier & Turner 2002, 221). I do not know whether the cartoon has ever been drawn and published.

The reconstruction processes that are required to determine whether either the cartoon or the joke represent argumentation develop in parallel[i]. Generally speaking both texts are just a sharp and funny way to express the opinion that Bill Clinton survives incidents that cost others – even those who are held to be unassailable – their position. In a specific context however it may be plausible to reconstruct a move in an argumentative discussion on the basis of this expressed opinion. In that case the texts can be said to represent this move[ii]. The expression fills a slot in a reconstructed discussion structure.

Suppose that shortly after January 17, 1998 – the moment that the world heard about the Lewinski affair – a Washington in-crowd democrat makes the joke to his or her colleagues or publishes the cartoon on the bulletin board. Given that context one can propose that by performing the communicative act this person takes up a role in a discussion, even though almost all elements of the discussion structure stay implicit. These elements can stay implicit because the context sufficiently indicates the discussion structure.

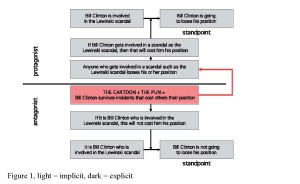

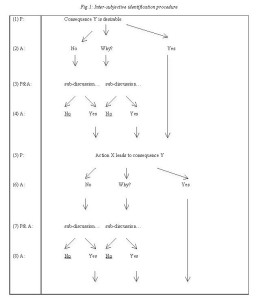

The following is a possible reconstruction. The person who makes the joke or publishes the cartoon projects a protagonist of a standpoint: Bill Clinton is going to lose his position, based on the argument that Bill Clinton is involved in the Lewinski scandal. A formulation of a minimally implied argument can be: If Clinton gets involved in a scandal as the Lewinski scandal, then that will cost him his position. Because more specific information is lacking one may assume that this implied argument rests on the more general argument: Anyone who gets involved in a scandal such as the Lewinski scandal loses his or her position. The person who makes the joke or publishes the cartoon fulfils the role of the antagonist. The antagonist questions the relevance of this more general argument, therefore questions the tenability of the minimally implied argument and therefore questions the standpoint. One may even say that he takes a standpoint himself, making the discussion a mixed discussion. The alternative that he expresses suggests a largely implicit but clear argumentation: Bill Clinton will not lose his position, because it is Bill Clinton who is involved in the Lewinski scandal. If it is Bill Clinton who is involved in the Lewinski scandal, this will not cost him his position, because Bill Clinton survives incidents that cost others – even those who were hold unassailable – their position = the joke or the cartoon (Figure 1) [iii].

We can conclude from this example that an image can be interpreted as the expression of an element of a complex speech act argumentation[iv]. From the realm of verbal argumentation it is clear that complex argumentative episodes can be represented with minimal textual means and that in many cases no explicit argumentative indication is added[v]. So we should not be surprised that an image can express information that leads to the reconstruction of a rather complex episode in an argumentative discussion. Images may not be suitable to express either general principles or illocutionary functions[vi]. However, to represent one or more moves in an argumentative discussion does not require that the warrant is explicitly expressed, nor that information is explicitly marked as a standpoint or as an argument. This obviously limits the argumentative use of purely non verbal images to specific contexts from which its argumentative function can be understood. Contexts are not always that informative. That is why we usually see non verbal images combined with verbal texts. Often the image presents information that functions as a set of data or as a backing, while the warrant or the standpoint are verbally expressed.

So when we compare a visual text (here the cartoon) with a functionally equivalent verbal text (here the pun), both texts call upon a similar body of knowledge in the reconstruction of the represented argumentation. This notion of (functional) equivalency is not a well defined theoretical concept. I use it to indicate a heuristic method to compare visual text fragments with verbal counterparts that express an equivalent position in the argumentative reconstruction[vii]. The idea is that maximizing the relevant similarities makes significant differences visible.

2. Iconicity in visual texts

In the next example we touch upon such a theoretically interesting difference. This difference concerns the division of labor between the narrator and the interpreter. Prototypically the narrator in a visual text presents a narrative in its iconic, mimetic value, while the narrator in a verbal text already embeds the narrative in a context of experiences (indexical values: if you observe A, this indicates B) and cultural habits (symbolic values: A is normal, understandable or good, B is marked, strange, not preferred, and so on)[viii]. This difference in what the (abstract) narrator is doing is reflected in a difference of the work to be done by the interpreter.

In an almost entirely non verbal advertisement clip we see a somewhat elder boxer, thickset but well-trained. He is initially knocked down by an aggressive looking, tattooed, skinhead opponent. While the referee is counting him out we see the boxer in flash-backs: as a nice little child, as a hard training adolescent, as the groom, as a family man, loved by his wife, his child, his coach, loved by a large crowd of friends. Then we see him, roused by his coach, muster up his courage and get up just in time to carry on the fight. A slogan appears: “Nu se termină acum. Acum începe” (Romanian for “It does not end now. Now it starts”). Finally we see the logo and name of the CEC Bank, with the words: Banca nostră.

I first present an argumentative interpretation of the visual text that is obvious to at least one Romanian reader[ix].

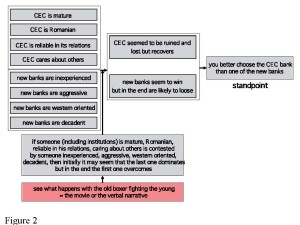

The implicit standpoint is (based on the ratio of this advertisement): You better choose the CEC bank than one of the new banks. The metaphor – as soon as recognized at the end of the movie – foregrounds a series of characteristics from both boxers and their story that can be meaningfully projected on CEC bank and competing financial institutions. From the boxers: CEC is mature, CEC is Romanian, CEC is reliable in his relations, CEC cares about others. The new coming banks are inexperienced, aggressive, western oriented and decadent. From the story is projected: CEC seemed to be ruined and lost but recovers. The new banks seem to win but in the end are likely to loose. An argumentative relation based on causality[x] is suggested between the first and the second projection. The implied argument is: if someone (including institutions) is mature, Romanian, reliable in his relations, caring about others is contested by someone inexperienced, aggressive, western oriented and decadent, then initially it may seem that the last one dominates, but in the end the first one overcomes. This implied argument is backed by the pictorial part of the clip.

This argumentative reconstruction is complicated and one can surely argue about the details. However, the way the metaphor is transformed into an argument based on analogy is familiar[xi]. In the reconstruction a set of relevant correspondences between the boxing match and the competition between banks is identified and successively reconstructed as an orderly set of propositions.

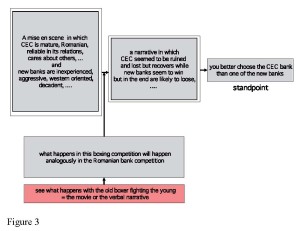

We can however also reconstruct an argumentation as in figure 3.

In this reconstruction the visual text has not been interpreted as an orderly set of propositions. The text is placed in an argument structure in its mimetic quality. In Peircean terminology this means that its iconic value is dominant. What is shown is (as yet) is dominant over what the discourse voice or the interpreter attaches to it on the basis of his or her experiences (index in Peirce’s terminology) and is dominant over the cultural values that the discourse voice or interpreter attach to it (symbol in Peirce’s terminology, diegesis in a narrative terminology). One may say that the work to transform its information into an orderly set of proposition still has to be done.

In both reconstructions the expressed information is perceived as a narrative[xii] that functions argumentatively as a backing. But it seems evident that the second reconstruction in figure 3 stays much closer to the iconic visual text than the first reconstruction in figure 2. However, when we try to construct a functionally equivalent verbal version of the visual text, we experience that it is difficult or at least feels rather artificial to construct a similar iconic verbal narrative, while the construction of a version with more attributive and evaluative propositions that is closer to the reconstruction in figure 2 appears as much more natural. We repeat the initial verbal description, now marking attributive and evaluative elements:

We see a somewhat elder boxer, thickset but well-trained. He is initially knocked down by an aggressive looking, tattooed, skinhead opponent. While the referee is counting him out we see the boxer in flash-backs: as a nice little child, as a hard training adolescent, as the groom, as a family man, loved by his wife, his child, his coach, loved by a large crowd of friends. Then we see him, roused by his coach, muster up his courage and get up just in time to carry on the fight.

This difference between the visual and the verbal mode is not coincidental. In a prototypical visual text the spectator needs to select the relevant information out of a sequence of shots to construct a coherent story from the text. It is also the spectator who forms hypotheses about explanations, who attributes motives and who evaluates. In a prototypical verbal text the narrator selects, explains, attributes and evaluates explicitly. This means however that the reader who wants to construct a more elaborated mental image of the story has to fill in the mise en scene. The reader has to imagine what the dynamics of a contrast ‘thickset – aggressive’ look like, what brings the narrator to a qualification family man, how the supportive friends actually behave and how they look, and so on.

In the verbal text many interpretations and evaluations are cut-and-dried presented already by the narrator. The narrator informs the reader that these people are friends and that what they do is supportive. In the visual text the spectator has to form these interpretative attributions and evaluations himself. The visual text is relatively more iconic, the verbal text is relatively more ‘symbolic’, embedded already in a conventional system of values and interpretations.[xiii]

This is a relative distinction. Visual texts have a powerful narrator too, in the cinematographic choices, in the editing, in the construction of the mise-en-scene, in the dynamics of the music. This narrator guides the selection of what is relevant for the story and can strongly suggest attributions and evaluations[xiv]. But in the visual text far less descriptive elaboration and far more attribution and evaluation is left to the spectator.

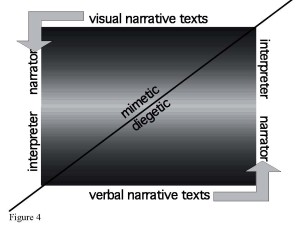

In a schema:

3. Iconicity in verbal texts

When the verbal mode is taken as the unique mode to express argumentation, it is plausible to associate argumentation with a rather directly expressed propositionality, because prototypically the narrator of a verbal text confronts the reader with an ordered set of logically connected propositions. The visual mode is then somewhat ‘inferior’, because now the spectator has to interpret the text as such a set of propositions. The interpreter has to transform an iconic reconstruction (figure 3) into a propositional reconstruction (figure 2), an unwished complication in the reconstruction process.

However if the verbal as well as the visual mode are both taken seriously as ways to express argumentation, we can bring up the following question: if a verbal text expresses a structure close to the propositional analysis (as in figure 2), does that not imply that now the interpreter needs to reconstruct its iconic values (as in figure 3)? If that is the case then there is at least on this aspect no reason to see the visual mode as a derivative. So the question is: is the narrative in its iconic value relevant for an argumentative reconstruction, or is it just an intermediate step? The answer seems to be that at least in some arguments the reconstruction of the text in its iconic value is far from just an intermediate step as the next example illustrates.

A short movie that was made by the defending counsel shows the suspect, a habitual offender, a year after the start of his trial [xv]. We see him as a member of a Christian community. The movie shows his life in the community and shows him explaining his motives and intentions.

Clearly the movie is meant to fill the ‘data – slot’ in an argument that supports a standpoint that a specific sanction should be imposed on this accused, namely a sanction that supports his will to improve. However, as in the CEC example, it is the interpreter who has to distil a set of ordered propositions from the movie: the relevant facts, leading to the relevant evaluations and attributions of motives. In other words when we stay close to the text a reconstruction of the narrative in its iconic value is adequate and this reconstruction needs to be transformed into a propositional one by the interpreter.

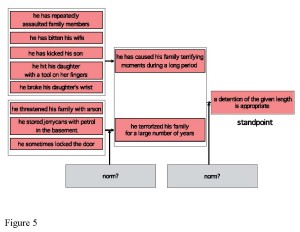

But now look at this almost literally translated part from a Dutch judicial decision. This is a verbal text in which the judge presents a set of ordered propositions. It seems functionally equivalent to the movie; it also presents information that is meant to support the standpoint that a specific sanction is appropriate.

Accused has terrorized his family for a large number of years. He has used disproportionate violence as an instrument to maintain authority in the family. Among other things he has repeatedly assaulted family members – regardless of their age – by beating them, also with a belt, and kicking them. He also has bitten his wife during a scrimmage which resulted in a bite wound. During a fight he has kicked his son, hit him and gave him a hard butt of the head. […] Furthermore, the accused has hit his daughter once with a tool on her fingers while her fingers rested on the table. On another occasion he has twisted her wrist and thereupon hit it with a hammer. This broke her wrist. […] Finally the accused has threatened his family repeatedly with arson. To enforce his threats he stored jerrycans with petrol in the basement. During such a threat he sometimes locked the door. Never his wife and children knew whether he was going to put his threats into effect. Because of this he has caused his family terrifying moments for a long period. […] Considering the above the court deems a […] detention of the following length appropriate[xvi].

Interpreted as a set of related propositions we may reconstruct an argumentation as in figure 4.

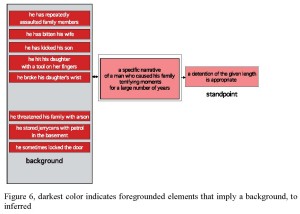

The position of the first and the one but last utterance is significant. Evidently there is not an a priori established norm that guides the inference from the facts to these utterances. That may be surprising in a carefully written formal decision. It is however less surprising if we search for and discover the iconicity of this text, which is a narrative schema. In that case we can reconstruct the text as in figure 6.

In this reconstruction we read the expressed descriptions as a plot, a foreground that evokes a background story filling in a large number of years with a continuous process of terror and suppression. The interpreter has to fill in this background. That does not mean that he has to make up all kind of other, not formally proven incidents. It means that he has to ‘read’ the propositions as a story that covers and characterizes a series of years.

This example illustrates that both stages in the argumentative reconstruction need to be recognized as relevant stages. From a formal legal point of view the list of propositions is relevant: each of them needs to follow from the presented evidence. This implies that a movie as presented by Jaap Bakker has to be transformed into a set of propositions as soon as formal legal proof of elements of it is required. However the iconic narrative expressed in Jaap Bakker’s visual text and implied in the background in this judge’s verbal text is relevant too. It is clear that the utterances in the text of the judge are meant to represent a story that is much more than only the ‘foregrounded’ events. That implies that the utterances are not only a set of propositions, related to the standpoint by an implicit argument that has a form “If proposition 1 to N, then it is reasonable to hold standpoint S”. The utterances are at the same moment a plot that should evoke a story that relates to the standpoint by an implicit argument that has a form “On the basis of this story it is reasonable to hold standpoint S”.

NOTES

[i] In line with the pragma-dialectical approach I understand argumentation as a complex illocutionary act that can be reconstructed as a move in a critical discussion. I use the terms (mixed) discussion, protagonist, antagonist, standpoint, argument, implicit argument in accordance with Van Eemeren & Grootendorst 2004, although the concept of a propositional content in their definition of the illocutionary act may turn out to require reconsideration.

[ii] Throughout this paper I intend to distinguish carefully between to represent and to express. We can argue that expressed elements in a context lead to a representation that is more than what is expressed.

[iii] Evidently the joke as well as the cartoon is able to convey a much richer meaning. That is the brilliance of them. The specific use of the Titanic for example can bring into mind the self-confidence, tending to arrogance, of the engineers and constructors, which can be projected on Clinton, and so on. This regards the visual as well as the verbal.

[iv] Whether a (solely) visual text can represent (or express?) argumentation leads to a sometimes heated debate. In the reference list I sum up some of the contributions. Often the question seems to be whether a visual text is an argument. Blair formulates: “That any of these paintings might have been an argument in other circumstances does not make it an argument as it stands” (1996, 28), strongly referring to intentions of the historical creator of the visual text, in casu Picasso. Such a position seems inadequate to me. (a) A verbal or visual text can be called upon by another than the historical author. (b) A function as an argument is first of all a matter of an (if one wants externalized and socialized) interpretation. Of course this may lead to a debate similar to that in narrative theories. Are there any textual features that characterize a text inherently as a narrative text? Ryan for example (2004, 9v) tries to make a distinction between being a narrative and possessing narrativity. To require that a text has to bear inherently in its form the argumentative function before calling it an argument seems in the verbal as well as in the visual domain an untenable position to me. (c) The term argument can refer to a ‘complete’ argumentative move in a discussion (neglecting the fact here that often it is not so easy to determine when a move is complete) or to an element from which (maybe in connection with other expressed elements) one can reconstruct such a complete move. This possibility seems to be neglected by some of advocates as well as the opponents.

[v] In Van den Hoven 2007 an argumentative analysis of two full newspaper articles shows that in more than 50% of all relations there is no explicit indication.

[vi] This claim is contested in Groarke (2002, 2007) as well as in Chryslee c.s. (1996), but strongly supported in Johnson 2003.

[vii] This method seems important to cleanse the debate whether and how visual texts that represent argumentation differ from verbal texts. To search for functional equivalence become even more important now that advocates as well as the opponents show such a strong preference for complicated visuals (cartoons, metaphorical texts in complicated advertisements, and so on). These require complicated analyses as in my first two examples. This suggests that visual texts – if they represent argumentation at all – do this in a very complicated way, so different from Socrates mortality that follows from his being human. If one constructs a verbal equivalent text, the analyses required by the verbal texts turn out to be just as complicated.

[viii] See for this interpretation of Peircean semiotics Van den Hoven 2009, and more specific Van den Hoven 2010.

[ix] Camelia-Mihaela Cmeciu presented me the outline of the interpretation that I use as the basis for the argumentative reconstruction (Cmeciu & Van den Hoven 2009).

[x] Causality is used here in a broad meaning, covering relations that run form cause to effect as well as from effect (as a symptom) to cause, and in the socio-physical domain as well as in the pragma-epistemic domain.

[xi] Whether the warrant should be formulated in a generalized form as I did here can be debated. But that regards the theoretical debate whether the argument on analogy requires this kind of generalization.

[xii] From a cognitive perspective we define a narrative text as a discourse (the plot) that invites the interpreter to construct a in some sense coherent series of events in their temporal sequence (a story).

[xiii] I prefer to use a terminology that refers to Peircean semiotics. There are two reasons. The first one is that the pair mimetic/diegetic strongly suggests an opposition, which is untenable. A more important reason is that Peircean semiotics can model the process in which a sign develops from its iconic value through its indexical value (the empirically motivated experiences) to its symbolic value (the habits attached). Compare Van den Hoven 2010. The idea that for example moving pictures are purely mimetic and lack a narrator is untenable. Bordwell & Thompson (2004) offer an elaborated neo-formalist analysis of these elements of a film narrator.

[xiv] Also compare the first of “five elements for developing a claim from a moving picture” that Alcolea-Banegas (2009) distinguishes.

[xv] Made by Jaap Bakker: see http://www.jaapbakker.com/

[xvi] An almost literal translation from LJN: AD5930, Rechtbank ‘s-Gravenhage 09/900408-01, November 16 2001.

REFERENCES

Alcolea-Banegas, J. (2009). Visual arguments in film. Argumentation, 23, 259-275.

Birdsell, D.S., & Groarke, L. (1996). Towards a theory of visual argument. Argument and Advocacy, 33, 1–10.

Blair, J.A. (1996). The possibility and actuality of visual arguments. Argumentation and Advocacy, 33, 23–29.

Bordwell, D., & Thompson, K. (2004). Film art: An introduction, 7th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Cmeciu, C.M., & van den Hoven, P. (2009). Representing tradition within the process of rebranding. Revistei Române de Jurnalism şi Comunicare, 3, 19-23.

Chryslee, G. J., Foss, S. K. & Ranney, A. L. (1996). The construction of claims in visual argumentation. Visual Communication Quarterly, (3), 9 – 13

Eemeren, F.H. van, & Grootendorst, R. (2004). A systematic theory of argumentation: The pragma-dialectical approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fauconnier, G., & Turner, M. (2002). The way we think. Conceptual blending and then mind’s hidden complexities. New York.

Groarke, L. (2002). Towards a pragma-dialectics of visual argument. In: F.H. van Eemeren (ed.), Advances in pragma-dialectics (pp. 137–151). Amsterdam: International Centre for the Study of Argumentation.

Groarke, L. (2007), Four theses on Toulmin and visual argument. In: F.H. van Eemeren, J.A. Blair, C.A. Willard & B. Garssen (ed.), Proceedings of the Sixth Conference ISSA. Amsterdam (pp. 535–540). Amsterdam: Sic Sat.

Hoven, P.J. van den (2007). Causale relaties: een onomasiologische benadering. Tijdschrift voor Taalbeheersing, 29(2), 97-134.

Hoven P.J. van den (2009). Peirceaanse semiotiek en tekstlinguïstische modellen. Tijdschrift voor taalbeheersing, 31(3), 195-213.

Hoven, Paul van den (2010). The intriguing iconic sign. In: Interstudia [to appear].

Johnson, R.H. (2003), Why “visual arguments” aren’t arguments. URL = <http://web2.uwindsor.ca/faculty/arts/philosophy/ILat25/edited_johnson.doc>.

Ryan, M. (Ed.) (2004). Narrative across media: The language of storytelling. University of Nebraska Press. Lincoln, London.

Slade, C. (2003). Seeing reasons: Visual argumentation in advertisements. Argumentation, 17, 145–160.

Tarnay, L. (2003). The conceptual basis of visual argumentation. In: F.H. van Eemeren, J.A. Blair, C.A. Willard, and A.F. Snoeck Henkemans (ed.), Proceedings of the Fifth Conference ISSA (pp. 1001–1005). Amsterdam: Sic Sat.