ISSA Proceedings 2010 – Visual Tropes And Figures As Visual Argumentation

During the latter part of the 20th century, and in particular during the last two decades, advertising has become increasingly visual (cf. Leiss et al. 2005, Gisbergen et al. 2004, Pollay 1985). Imagery now dominates advertising. Considering advertising as a kind of argumentation, we may ask how we actually argue by means of pictures, or more specifically, how we argue with ads that are predominantly visual.

During the latter part of the 20th century, and in particular during the last two decades, advertising has become increasingly visual (cf. Leiss et al. 2005, Gisbergen et al. 2004, Pollay 1985). Imagery now dominates advertising. Considering advertising as a kind of argumentation, we may ask how we actually argue by means of pictures, or more specifically, how we argue with ads that are predominantly visual.

In this article, I will argue that visual rhetorical figures in advertising – meaning both tropes and figures – are not only ornamental, but also support the creation of arguments about product and brand. My claim is that rhetorical figures direct the audience to read arguments into advertisements that are predominantly pictorially mediated. Pictures are ambiguous, but rhetorical figures can help limit the possible interpretations, thus evoking the intended arguments.

1. Pictorial Argumentation

This article limits itself to examining a certain kind of pictorial argumentation, namely visual tropology in commercial advertising. However, it should be acknowledged that several works have accounted for the existence and nature of visual argumentation in general (e.g. Finnegan 2001, Birdsell & Groarke 2007, Kjeldsen 2007, Groarke 2009). Drawing upon such works, we may assume that, in spite of the reservations of some researchers (e.g. Flemming 1996, Johnson 2004), it is both possible and beneficial to consider pictures and other instances of visual communication as argumentation. My own view is that visual argumentation is characterised by an enthymematic process, in which the visuals (e.g. pictures) function as cues that evoke intended meanings, premises and lines of reasoning. This is possible because an argument, whether visual or verbal, is not a text, or “a thing to be looked for, but rather a concept people use, a perspective they take” (Brockreide 1992). Argumentation is communicative action, which is performed, evoked, and must be understood in a rhetorical context of opposition.

I have suggested elsewhere (e.g. Kjeldsen 2001, 2002) that pictorial rhetoric can be characterised by four specific visual qualities: 1) the power to create presence (evidentia), 2) immediacy in perception, 3) realism and indexical documentation, and finally 4) semantic condensation. Semantic condensation can be both emotional (evoking emotions) and rational (evoking arguments and reasoning).

Pictures, I suggest, argue primarily by means of context and condensation. They offer a rhetorical enthymematic process where something is omitted, and, as a consequence, the spectator has to provide the unspoken premises. Rational condensation in pictures, then, is the visual counterpart of verbal argumentation. However, the spectator needs certain directions to be able to (re)construct the arguments, i.e. some cognitive schemes to make use of.

Sometimes, such schemes may be found in the context itself, such as in the circumstances of the current situation (cf. Kjeldsen 2007). At other times – particularly in advertising – the viewer’s (re)construction of arguments is enabled through visual tropes and figures. Metaphor and metonymy, synecdoche and hyperbole, ellipsis and contrasts are among the most common types of visual argumentation (e.g. Kjeldsen 2000, 2008, McQuarrie & Mick 2003, Forceville 2006).

No print advertisement is entirely without words, however. Verbality in ads can be either found as written words, as the name of the product or even as the viewers’ mental concepts for interpretation. Despite this, the dominance of the pictorial renders the question of visual argumentation pertinent. According to semiotics, verbal communication employs an arbitrary code, and pictures an iconic one. Viewed as a code based on motivated signs, a picture is perceived to have either no articulation or only second-order articulation (cf. Barthes 1977, Eco 1979, Chandler 2006).

Consequently, “pertinent” and “facultative” signs in pictures cannot be clearly distinguished. Umberto Eco, among others, suggests that the iconic coding in pictures is weak (Eco, 1979, p. 213). This means that pictures lack the syntax to guide the viewers to determine precisely what the different elements might mean or how these elements should be semantically connected.

This might seem to suggest the exclusion of the possibility that pictures can make arguments – and it would mean that advertisements would have to let the words do the argumentation. However, by accepting the fact that most print advertising is predominantly visual and the claim that advertising is argumentation, we should acknowledge that pictures in advertisements do in fact perform argumentation – or at least play an important role in establishing arguments in advertisements (cf. Ripley 2008, Kjeldsen 2007, Slade 2003).

On the other hand, some claim that advertising is not really argumentation, but rather a subconscious and irrational kind of psychological persuasion (Johnson & Blair 1994, p. 225, Blair 1996, cf. Slade 2003). However, the fact that theoretical definitions, demarcations, delineations, and descriptions of argument from Aristotle to van Eemeren actually fit advertising communication quite nicely suggests that “an ad is indeed an argument” (Ripley 2008, cf. Slade 2002, 2003). I should probably add that the ability of pictures and advertisements to provide arguments does not ensure that all such arguments are good, valid or convincing.

2. Reconstruction of Pictorial Argumentation through Context

One of the ways pictures are able to produce argumentation is their use of the viewer’s knowledge of the situation and context that will allow the viewer to (re)construct the argument herself (cf. Kjeldsen 2007). However, this requires a particular kind of situation that will lead the viewer to perceive the image as a piece of argumentation and provide enough cues to let the viewer construct the argument. Situations or circumstances that help the viewer to evoke the arguments must entail a context of opposition.

Establishing claims, premises and their connection through such contextual knowledge is more readily done in ongoing debates and in specific, well-defined situations – something we encounter in politics from time to time. In such circumstances, the visual will be able to tap into existing and already proposed arguments. As an illustration of this fact, let us take a closer look at a cartoon of the NATO Secretary General, Anders Fogh Rasmussen.

The drawing was published in the Danish newspaper Politiken (9 Dec. 2001)[i] while Fogh Rasmussen was the Prime Minister of Denmark. It shows the standing, unshaven Prime Minister in frontal pose, looking directly at the viewer. He is removing his suit jacket, revealing himself as an ancient cave man wearing a shaggy animal hide.

The cartoon only makes sense if we are aware that Anders Fogh Rasmussen was known as an economic liberalist, and the author of the book “From the Social State to the Minimal State”.[ii] He was a proponent for limiting state intervention in the life of individuals, claiming that everyone would be better off fending for themselves. While most people outside Denmark would not be able to make rhetorical sense of the cartoon without this piece of information, it enthymematically tapped into an ongoing debate in Denmark about limiting the Danish welfare state. The cartoon is not an illustration, since it is not accompanied by a text, and it is more than just a visual statement, because it invites the viewer to construct a metaphorical argument against the Prime Minister; the cartoon argues that under the classy suit, the Prime Minister is really a political cave man, a primitive social Darwinist, who does not acknowledge or care for people unable to fend for themselves and in need of a proper welfare state to help them.

Contextual decoding, as required in the above example, might be more difficult in commercial advertising, where the viewer is usually unable to connect the particular text to any specific circumstances, debates or discourses. All we have is knowledge of the general genre and its aim: to sell products and to promote brands.

As a general rule, advertising cannot be regarded as a mixed difference of opinion, where two parties hold opposing standpoints (cf. Eemeren et al. 2002, p. 8ff.). Advertising communication is best described as a single, non-mixed difference of opinion; only one party (the advertiser) is committed to defending only one standpoint. Because we know the context of this difference of opinion, we also know the stated aim: “Buy this!” This is a proposition shared by all commercial advertising. No matter what an advertisement communicates, it will always, either directly or indirectly, carry this claim.

This ultimate proposition may be called the final claim. Knowing the context and the final claim, every viewer is provided with a starting point for discovering the premises supporting the final claim, and in this way reconstructing the argumentation. We should, of course, not forget that advertising also performs other argumentative functions (or claims) such as enhancing a company’s image and reputation (ethos). Much contemporary commercial advertising aims more at brand reputation than directly encouraging consumers to buy the product. In such advertisements, a penultimate claim argues for the character or quality of the brand, claiming something along the lines of “This brand/company is cool/socially responsible/high class”.

Because of the artful execution of the advertisements I analyse in the present text, it would also be possible to extract such ethos argumentation, forwarding propositions such as: “This is an artful and intelligent advertisement, so the product/brand/user must be artful and intelligent”. In this text, however, I will only be examining argumentation entailing the final claim “Buy this!”

3. Reconstruction of Pictorial Argumentation through Rhetorical Figures

In the hermeneutic circumstances of advertising, the use of rhetorical figures may help guide the viewer to making the intended inferences. Figures are constituted by certain recognisable patterns: A metaphor requires viewing something in light of something else; a contrast requires opposites; and a chiasmus is only a chiasmus if it presents a repetition of ideas in inverted order.

Thus, the figurative presentation controls the interpretation by letting the viewer notice “an artful deviation in form that adheres to an identifiable template” (McQuarrie and Mick 1996). This kind of augmented control is possible (Philips & McQuarrie 2004, p. 114):

because the number of templates is limited, and because consumers encounter the same template over and over again, they have the opportunity to learn a response to that figure. That is, through repeated exposure over time consumers learn the sorts of inference operations a communicator desires the recipients to undertake […]. Because of this learning, rhetorical figures are able to channel inferences.

So, rhetorical figures may function argumentatively by directing the viewer’s attention toward certain elements in the advertisement and offering patterns of reasoning. This guides the viewer towards an interpretation with certain premises that support a particular conclusion.

This understanding of rhetorical figures as patterns of thought and reasoning was not prominent in classical rhetoric. Modern theory of rhetoric has, however, acknowledged these epistemological and argumentative dimensions.

The works of Lakoff and Johnson (1980), Jeanne Fahnestock (2004), Christian Plantin (2009), and, of course, Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca (1971) have illustrated the argumentative character of rhetorical figures. Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca reject the common view of tropes and figures as pure ornament. Tropes and figures may be embellishment, but sometimes they are best considered as a form of argumentation. They consider (1971, p. 169):

a figure to be argumentative, if it brings about a change of perspective, and its use seems normal in relation to this new situation. If, on the other hand, the speech does not bring about the adherence of the hearer to this argumentative form, the figure will be considered an embellishment, a figure of style. It can excite admiration, but this will be on the aesthetic plane, or in recognition of the speaker’s originality.

According to Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca, tropes and figures may bring about a change in perspective in three ways: They may impose a choice, increase the impression of presence, and they may bring about communion with the audience (ibid.). Christopher Tindale provides a slightly more technical explanation of the argumentative dimensions of rhetorical figures. Like arguments, they are “regularised patterns, or codified structures that transfer acceptability from premises to conclusions” (2004, p. 73).

These argumentative changes in perspective and the transference of acceptability are also possible in pictures, because communication through tropes and figures such as metaphors, metonymies or contrasts is not a verbal, but a cognitive phenomenon (cf. Lakoff & Johnson 1980, McQuarrie and Mick 2003, Forceville 2006, Kjeldsen 2002, 2007).

Furthermore, pictorial tropes and figures are potentially more efficient than words in increasing the impression of presence, since pictures actually show us what words can only tell us. Pictorial tropology is also, I suggest, at least equally as efficient in imposing choice and bringing about communion. Thus, the formal character of tropes and figures may also be found in pictures, and help elicit lines of reasoning evoked visually.

4. Examples of Pictorial Argumentation established by Rhetorical Figures

If figures “are to be recognised as arguments”, whether verbal or visual, “they will need to encourage the same movement within a discourse, from premise to conclusion.” (Tindale 2004: 73). In order to show how a rhetorical figure may help the viewer construct the argument of the advertisement, I will provide a few examples of how visual figures encourage the transfer of acceptability from premise to conclusions in commercial advertising.

The first ad is for Energizer Batteries. The brief was to increase sales of Energizer Lithium Batteries over the Christmas period. Because of the large number of batteries intended for toys commonly purchased over the Christmas period, parents were identified as the target audience. The picture shows a boy standing in a garage or a workshop. Behind him is a cupboard with paintbrushes and paint. He holds a brush with red paint in his right hand, smiling down at a white, unwitting dog sitting next to him.

The first ad is for Energizer Batteries. The brief was to increase sales of Energizer Lithium Batteries over the Christmas period. Because of the large number of batteries intended for toys commonly purchased over the Christmas period, parents were identified as the target audience. The picture shows a boy standing in a garage or a workshop. Behind him is a cupboard with paintbrushes and paint. He holds a brush with red paint in his right hand, smiling down at a white, unwitting dog sitting next to him.

What might the viewer’s route of interpretation look like when attempting to decode this ad? When trying to make sense of the ad, the viewer will search the picture’s central elements for any clues to its meaning. Firstly, the viewer might notice the boy looking at the dog while holding a paintbrush in his hand. Secondly, the viewer might notice the product logo and slogan in the lower left-hand corner: “Energizer. Never let their toys die. The world’s longest lasting battery. Energizer.” Since neither the slogan nor the picture make much sense on their own, the viewer must look for the connection between the two in order to make sense of them together. Confronted with the proposition: ”Never let their toys die”, the viewer is inclined to question why, and then to seek an answer in the image. Seeing the boy, who is looking at the dog, the viewer is invited to question what is actually taking place. What does the picture (and the ad as a whole) say? The answer is found when the viewer infers what the boy might be thinking and what he is about to do. In Toulmin’s terms, the intended argumentation can be (re)constructed more or less like this:

Final claim 1: Buy this battery.

Ground 1: It will keep the toys working (for a long time).

Warrant 1: You want to keep your toys working for a long time.

Claim 2 (warrant 1): You want to keep your toys working for a long time.

Ground 2: Working toys keep children occupied.

Warrant 2: You want to keep your children occupied.

Claim 3 (warrant 2): You want to keep your children occupied.

Ground 3: Children who are not occupied cause unfortunate events to happen.

Warrant 3: You do not want unfortunate events.

Backing 3: You do not want the kids to paint your dog.

Refraining from showing what will happen, the ad makes use of a visual ellipsis. Through omission, it invites an enthymematical construction of an argument based on a causal argument scheme (cf. Eemeren & Grootendorst 1992, Eemeren et al. 2002, Eemeren & Grootendorst 2003) proposing that buying Energizer Batteries will lead to the prevention of unfortunate events. The implicit story in the ad has a somewhat hyperbolic character, which seems to be a common trait among many of the ads eliciting arguments through visual figures. The exaggeration helps make the meaning – and argument – clear.

We can see the same kind of elliptic and hyperbolic character in an ad for Kitadol, a pharmaceutical brand manufactured in Chile. The product is designed to help women cope with the effects of menstrual pain and abdominal swelling. It was promoted in a print advertising campaign aimed at women’s male partners. In the ads, the women were replaced with a boxer, a wrestler and a Thai boxer. The tag line is “Get Her Back”, followed by the brand name and indication of use: “Kitadol Menstrual period”. The campaign won a Silver Press Lion at the Cannes International Advertising Festival 2010.

How does this ad work rhetorically?

How does this ad work rhetorically?

We look at the picture and realise that something is not quite right. The boxer does not seem to belong in this particular setting. He is placed exactly where a woman, i.e. a wife and a mother, would normally sit. The boxer and the man reading the paper exhibit the nonverbal behaviour that we would normally recognise as the interaction between man and woman in a tense or strained relationship. The man is looking nervously at the boxer, and the boxer has turned his back on the man while staring sourly into the adjacent child’s stroller.

Hence, in accordance with relevance theory (Sperber and Wilson 1986), we realise that the boxer does not belong in this setting, and we have to replace him with something else if the advertisement is to have any relevance for us, or if it is to make any sense at all. The picture creates an implicature[iii], an implicit assumption, which the viewer has to transform into an explicit proposition, namely the metaphoric claim that “female spouses are (like) aggressive boxers when they have their periods”. Since a major part of this proposition is visually manifest (we can actually see an aggressive boxer), we may consider the proposition as strongly implicated (Sperber & Wilson 1986, p. 194ff., Forceville 2006, p. 90ff.)

Taken together, the genre, the knowledge of the brand, the final claim and the metaphorically communicated implicature invite the viewer to a line of inference that will be something like this:

Female spouses are (like) aggressive boxers when they have their periods.

Kitadol removes this aggressiveness.

Therefore you should buy Kitadol (for your wife).

In Toulmin’s model, it can be described like this:

Final claim: You should (Q: really) buy Kitadol.

Ground: Female spouses are (like) aggressive boxers when they have their periods.

Warrant: Kitadol removes this aggressiveness.

Of course, the key to the correct figurative interpretation is the brand name and the slogan “Get her back”, which indicates that your spouse is gone because she has mutated into an aggressive monster. This invites a similar line of reasoning:

Claim: Your spouse is gone.

Ground: She has turned into an aggressive boxer (because of her period).

Warrant: When your spouse has turned into an aggressive boxer, she is gone.

This connects to an argument, with the slogan functioning as claim:

Claim: You should get your spouse back.

Ground: She has turned into an aggressive boxer.

Warrant: When your wife turns into an aggressive boxer, you should get her back.

Often, it makes the most analytic sense to view the figurative implicature (which is partly manifest here) as a ground in the argument; however, it may also make sense to view the implicature as backing. Because both ground and backing usually emerge as facts, evidence and categorical statements, they appear to be more readily expressed visually than warrants do:

Claim: You should get your spouse back.

Ground: She has changed.

Warrant: Menstrual periods change women.

Backing: During their periods, spouses behave like aggressive boxers.

The different possibilities of argument construction outlined above illustrate that visual figures may offer several avenues of interpretation to one main argument. However, they also illustrate one of the challenges with analysis of predominantly pictorial argumentation. Because of the semiotic character of pictures, they often do not give the viewer any clear signs of what the different elements of the argument are, or how they should be connected.

Compared with verbally dominated argumentation, pictures do not allow for the same kind of indicators of argumentation (cf. Eemeren et al. 2002, p. 39). Furthermore, pictures do not generally provide us with indicators such as because, therefore or with the exception of. Neither do they offer much help in determining and distinguishing between claim, ground, warrant, backing or qualifier.

However, even though it may be difficult to establish a single and undisputed reconstruction of the argument, the figurative explicature provides the consumer with clear directions to the main argument for buying Kitadol: It will bring their spouses back. We might analytically reconstruct the main line of argument in many ways, but to the viewer, I propose, the argument is still pretty obvious.

Through a visual hyperbolic metaphor, the ad helps the viewer construct an argument based on a causal argument scheme (cf. Eemeren & Grotendorst 1992, Eemeren et al. 2002, Eemeren & Grotendorst 2003), suggesting that buying Kitadol will lead to the solution of a pertinent problem.

Hopefully, these two examples have illustrated how visual figures invite the construction of arguments. Once we acknowledge this persuasive ability in predominantly pictorial communication, we may be able to more readily recognise this kind of visual argumentation in similar ads. Without any elaborate analysis, we may, for instance, recognise the argument in the ad from the Israeli bookstore chain Steimatzky: The visually manifest part of the implicature in the ad is the shrunken head. It is a visual metaphor evoking an argument based on a causal argument scheme, and it proposes that if you don’t read, your brain will shrink. The reasoning can be rendered like this:

Final claim 1: Buy books.

Final claim 1: Buy books.

Ground 1: You should read more.

Warrant 1: If you buy more books, you read more.

Claim 2 (Ground 1): You should read more.

Ground 2: If you watch TV instead of reading, your brain will shrink and become underdeveloped (you will become stupid).

Warrant 2: You don’t want an underdeveloped brain.

Claim 3 (Ground 2): If watch TV instead of reading, your brain will shrink and become underdeveloped (you will become stupid).

Ground: Reading is like exercise or food for your brain.

Warrant: What you do not exercise or feed will shrink and become underdeveloped.

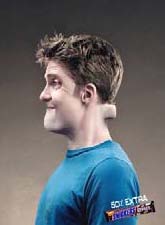

Whereas most visual figures seem to invite arguments based on causal argument schemes, we can also find advertising argumentation based on other kind of schemes. In an ad for the Snicker’s chocolate bar, we once again encounter a hyperbolic representation, this time through bodily distortion, creating an argument based on a symptomatic argument scheme, claiming that Snickers belong to the categories of big things:

Final claim 1: Buy this Snickers.

Final claim 1: Buy this Snickers.

Ground 1: It is big.

Warrant 1: You should buy big chocolates.

Claim 2 (Ground 1): It is big.

Ground 2: If you put it into your mouth it will stick out of your neck.

Warrant 2: Anything that will stick out of your neck after you put it into your mouth is big.

5. Conclusion

Visual figures hold a special rhetorical potential in persuasive communication because they allow for interpretative openness and active involvement while simultaneously providing clear directions that guide the viewer towards certain arguments.

The ads using visual figures are open to interpretation concerning the connotations of the different elements shown. In the Energizer ad, we may think of different things in connection with the garage as a place, with being a boy or with the pleasure or pain dogs may provide. As described by Eco (1979, 1989), such interpretative possibilities are characteristic of open texts. The necessary participation of the viewer in constructing the meaning and arguments of the ads also distinguish such open texts.

Ketelaar, Gisbergen and Beentjes (2008) have argued that such open ads have the common characteristic that consumers are not manifestly directed toward a certain interpretation, and that the presence of rhetorical figures are one of five antecedents rendering an advertisement more open; the others being presence of a prominent visual, absence of the product, absence of verbal anchoring, and a low level of brand anchoring.

However, my analysis of the above advertisements indicates that the presence of rhetorical figures actually helps delimit the possibilities of interpretation, hence creating not an open ad, but rather an ad that is open in some respects and closed in others. It is closed in the sense that particular rhetorical figures guide the viewer’s construction of the arguments in the ad in question.

The rhetorical figures thus help create relatively straightforward arguments. These arguments may prove complex when analysed, but may, nonetheless, be relatively easily decoded by the viewer, presuming of course that the viewer’s attention has been caught. Hence, ads using visual figures bear the characteristics of a closed text in Umberto Eco’s sense. The openness in the advertisements does not obstruct or obscure the lines of reasoning offered by visual figures; the cognitive participation of the viewer in creating the reasoning is controlled by the formal characteristics of the visual figures.

While hopefully my brief analyses have indicated the argumentation embedded in these advertisements, they may also have given the impression that pictorial argumentation is simply a matter of extracting verbal lines of reasoning and presenting them in argumentation models. This is clearly not the case. Pictorial communication simply cannot be transformed into verbal propositions. There is a difference between the two modes of representation. Pictures and visual figures provide vivid presence (evidentia), realism and immediacy in perception, which is difficult to achieve with words only. We can actually see the big boxer and are invited to feel the pain he may inflict and experience the similarities between him and a spouse in a bad mood. In this manner, the semantic condensation of pictorial representation has the ability of performing a sort of “thick description” (cf. Geertz 1973) in an instant, while providing both a full sense of an actual situation and an embedded narrative. This “thickness” disappears when we reduce the pictorial representation to “thin” propositions. Nevertheless, if we are to understand the rhetorical potential of the advertisements, we must reconstruct and explain the arguments they offer. This is best done through words and models. We just have to bear in mind that this is only part of the rhetorical and argumentative potential of advertisements that are predominantly pictorial.

NOTES

[i] The cartoon can be seen at: http://politiken.dk/fotografier/reportagefoto/article657481.ece (drawing no. 2) .

[ii] The Danish title is: “Fra socialstat til minimalstat – En liberal strategi” (Samleren, København 1993).

[iii] Explicatures are assumptions that are explicitly communicated: ”an explicature is a combination of linguistically encoded and contextually inferred conceptual features. The smaller the relative contribution of the contextual features, the more explicit the explicature will be, and inversely” (Sperber and Wilson 1986, p. 182).

REFERENCES

Birdsell, David & Leo Groarke. 2007. Outlines of A Theory of Visual Argument. Argumentation & Advocacy 43, 103-113.

Blair, J.A. (1976). The Possibility and Actuality of Visual Argument. Argumentation and Advocacy 33, 1-10.

Brockriede, W. (1992). Where is Argument. In W.L. Benoit, D. Hample, & P.J. Benoit (Eds.), Readings in Argumentation (pp. 73-78).

Eco, U. (1979). The Role of the Reader. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Eco, U. (1989). The Open work. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Chandler, D. (2006). Semiotics. The Basics. New York: Routledge.

Eemeren, F. H. van, & Grootendorst, R. (1992). Argumentation, Communication, and Fallacies: a Pragma-dialectical Perspective. Hillsdale, N.J.: L. Erlbaum.

Eemeren, F. H. van, Grootendorst, R., Snoeck Henkemans, F. (2002). Argumentation: Analysis, Evaluation, Presentation. Mahwah, NJ: L. Erlbaum.

Eemeren, F.H. van, & Grootendorst, R. (2003). Systematic Theory of Argumentation: The Pragma-Dialectical Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fahnestock, J. (2004). Figures of Argument. Informal Logic, 24(2), 115-135.

Finnegan, Cara A. (2001). The naturalistic enthymeme and visual argument: photographic representation in the ”skull controversy”. Argumentation and Advocacy, 37, 133-149.

Fleming, David (1996). Can Pictures Be Arguments? Argumentation and Advocacy, 33, 11-22.

Forceville, C. (2006 (1996)). Pictorial Metaphor in Advertising. New York: Routledge.

Geertz, C. (1973). Thick Description: Toward an Interpretive Theory of Culture. In The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays (pp. 3-30). New York: Basic Books.

Groarke, Leo. (2009). Five Theses on Toulmin and Visual Argument. In F.H. van Eemeren B. Garssen (Eds.), Pondering on Problems of Argumentation (pp. 229-239). Amsterdam: Springer.

Johnson, R. H. & Blair, J.A. (1994). Logical Self-Defense. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Johnson, Ralph H. (2004). Why ‘Visual Arguments’ aren’t Arguments. In Hans V. Hansen, Christopher Tindale, J. Anthony Blair, and Ralph H. Johnson (Eds.), Informal Logic at 25, CD-ROM. Winsor, Ont.: U of Winsor 2004.

Ketelaar, P., Gisbergen, M.S. & Beentjes, J.W.J. (2008). The Dark Side of Openness for Consumer Response. In McQuarrie, E.F., Phillips, B.J. (Eds.), Go figure. New Directions in Advertising Rhetoric. Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe.

Kjeldsen, J. E. (2000). What the Metaphor could not tell us about the Prime Minister’s Bicycle Helmet. Rhetorical Criticism of Visual Rhetoric. Nordicom Review, 21(2), 305-327.

Kjeldsen, J. E. (2001). The Rhetorical Power of Pictures. In Jostein Gripsrud & Fredrik Engelstad (Eds.), Power, Aesthetics, Media (pp. 132-157). Oslo: Unipub forlag.

Kjeldsen, J. E. (2002). Visuel retorik [Visual Rhetoric]. PhD. Thesis. Department of Media Studies. University of Bergen. Norway.

Kjeldsen, J. E. (2003). Talking to the Eye – Visuality in Ancient Rhetoric. Word & Image, 19(3), 133-137.

Kjeldsen J. E. (2007). Visual Argumentation in Scandinavian Political Advertising: A Cognitive, Contextual, and Reception Oriented Approach. Argumentation & Advocacy, 43, 124-132.

Kjeldsen, J. E. (2008). Visualizing egalitarianism – political print ads in Denmark. In Jesper Strömbäck, Toril Aalberg & Mark Ørsten (Eds.), Political Communication in the Nordic Countries (pp. 139-160). Göteborg: Nordicom.

Lakoff, G.. & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors We Live By. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Leiss, W., Kline, S., Jhally, S., & Botterill. J. (2005). Social Communication in Advertising. Consumption in the Marketplace. New York: Routledge.

McQuarrie, E. F., & Mick, D.G. (1996). Figures of Rhetoric in Advertising Language. Journal of Consumer Research, 22, 424-437.

McQuarrie, E. F. & Mick, D.G. (2003). The Contribution of Semiotic and Rhetorical Perspectives to the Explanation of Visual Persuasion in Advertising. In L. Scott & R. Batra (Eds.), Persuasive Imagery: A Consumer Response Perspective (pp. 191-221). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Perelman, C. & Olbrechts-Tyteca, L. (1971 (1969)). The New Rhetoric: A Treatise on Argumentation. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

Philips, B. J. & McQuarrie, E. F. (2004). Beyond Visual Metaphor: A New Typology of Visual Rhetoric in Advertising. Marketing theory, 4, 113-136.

Plantin, C. (2009). A Place for Figures of Speech in Argumentation Theory. Argumentation, 23, 325-337.

Pollay, R. (1985) The Subsiding Sizzle: A Descriptive History of Print Advertising 1900-1980. The Journal of Marketing. 49(3). 24-37.

Ripley, M. L. (2008). Argumentation Theorists Argue that an Ad is an Argument. Argumentation, 22, 507-519.

Slade, C. (2002). Reasons to Buy: The Logic of Advertisements. Argumentation, 16, 157-178.

Slade, C. (2003). Seeing Reasons: Visual Argumentation in Advertisements. Argumentation 17, 145-160.

Smith, V. (2007). Aristotle’s Classical Enthymeme and the Visual Argumentation of the Twentyfirst century. Argumentation and Advocacy, 43, 114-123.

Sperber, D. & Wilson, D. (1986) Relevance: Communication and Cognition. Oxford: Blackwell.

Tindale, C. (2004). Rhetorical Argumentation. Principles of Theory and Practice. Thousands Oaks: California.

van Gisbergen, M. S., Ketelaar, P.E. & Beentjes, H. (2004). Changes in Advertising? A Content Analysis of Magazine Advertisements in 1980 and 2000. In Peer Neijens, C. Hess, B. van der Putte & E. Smith (Eds.), Content And Media Factors in Advertising (pp. 51-61). Amsterdam: Het Spinhuis.

Credits for ads

Ad number 1:

Energizer Batteries: “Never let their toys die. The world’s longest lasting battery. Energizer”

Advertising Agency: DDB South Africa

Creative Director: Gareth Lessing

Art Director: Julie Maunder

Copywriter: Kenneth van Reenen

Photographer: Clive Stewart

Published: December 2007

Link to ad: http://adsoftheworld.com/media/print/energizer_lithium_batteries_paint?size=_original

Ad number 2:

Kitadol menstrual period: “Get her back”

Advertising Agency: Prolam Y&R, Santiago, Chile

Executive Creative Director: Tony Sarroca

Creative Director: Francisco Cavada

Art Director: Jorge Muñoz

Copywriters: Fabrizio Baracco, Cristian Martinez

Account manager: Francisco Cardemil

Link to ad: http://adsoftheworld.com/media/print/kitadol_menstrual_period_boxer?size=_original

Courtesy of: Y&R

Ad number 3:

Steimatzky book chain: “Read more”

Advertising Agency: Shalmor Avnon Amichay / Y&R Interactive Tel Aviv, Israel

Chief Creative Director: Gideon Amichay

Creative Director: Tzur Golan

Creative Team Leader: Amit Gal

Art Director: Ran Cory

Copywriter: Geva Kochba

Link to ad: http://adsoftheworld.com/media/print/steimatzky_read_more?size=_original

Courtesy of: Shalmor Avnon Amichay / Y&R Interactive Tel Aviv

Ad number 4:

Snickers chocolate: “50% extra”

Advertising Agency: The Assistant

Creation: J.O & J.B

Photography: K. Meert

Published: 2007

Link to ad: http://adsoftheworld.com/media/print/snickers_big?size=_original