ISSA Proceedings 2010 – Rhetorical vs. Syllogistic Models Of Legal Reasoning: The Italian Experience

1. Introduction

1. Introduction

The aims of this paper are (1) to outline the historical path that gradually led to the formation of a meta-discursive space founded upon argumentative accounts in Italian jurisprudence after the end of the Second World War, but without entering into detailed criticism of these accounts and their applications; (2) to identify, within such space, a peculiar approach (at once metaphysical and practice-oriented) which started from some universities in North-East Italy (Padua, Trento, Verona, Trieste). Following the basic studies of Francesco Cavalla, this approach has to date produced a research centre (CERMEG: Research Centre on Legal Methodology) and numerous scientific and experimental initiatives. Its representatives are known in Italy for their activities in the specific field of legal rhetoric – that is, the rhetorical method applied to legal reasoning – and for their cooperation with lawyers’ associations.

2. An historical reconstruction of Italian Jurisprudence after the Second World War

After the Second World War and the experience of legal positivism as an instrument of political coercion, the world’s ideological division in two opposing blocs – liberal-democrat and social-communist – produced in Italian jurisprudence an antagonism between proponents of natural law (understood as a limit to the state’s power) and those favourable to legal positivism (understood as a guarantee of the rule of law). The tradition of legal thought connected with neo-idealism, and considered excessively compromised with the fascist regime, disappeared. The phenomenological, existentialist and intuitionist currents of philosophy that developed between the two world wars resisted precise translation into the terms of legal philosophy. Curiously, the new supporters of legal positivism, all connected with the Turin School founded by Norberto Bobbio, mainly relied on the logical neo-empiricism of the Vienna Circle, despite the already ongoing crisis of neo-positivism. As a consequence, the theoretical and methodological formalism distinctive of nineteenth-century legal positivism and Kelsenian theory continued to characterize Italian jurisprudence, encountering only very weak opposition (also political) from the supporters of natural law.

The legal positivism inspired by Bobbio thus tended to convey into legal science a sort of ‘resurgent scientism’ apparently unaware of the discussions (as conducted by Edmund Husserl for example)[i] concerning the crisis of the sciences. It was dominated by the desire to furnish scholars of theory of law and specialists (in civil, criminal, constitutional, etc., law) with a rigorous method able to give the same logical certainty distinctive of the sciences, especially the formal ones, to jurisprudence.

We can therefore distinguish the following main features in this new legal positivism: axiom of axiological neutrality (based on David Hume’s Great Divide)[ii]; adoption of the analytical method (formalism), or, in some cases, of the empirical method (legal realism, sociology of law). These scholars believed that the certainty of the law, also in theory, could be ensured by assuming the postulate that by ‘law’ is meant a ‘set of positive legal norms’ – a postulate favoured by the codified regimes typical of the continental civil law countries. Bobbio himself applied the normativist formalist scheme developed by Hans Kelsen[iii] as the guarantee of a scientific jurisprudence. We may therefore say that the experiment proposed by Bobbio consisted in a merger between Kelsen’s normativism and neo-empiricist doctrines, that is, between normative rationality and logical rationality. A problematic undertaking indeed.

However, it was again Bobbio[iv], in his preface to the Italian translation of Traité de l’argumentation by Chaïm Perelman and Lucie Olbrechts-Tyteca (1966: the same year in which the so-called ‘crisis of legal positivism’ began), who opened a small breach in the rigid neo-positivist separation between rational certainty (the exclusive preserve of demonstrative reasoning) and the irrationality of all other kinds of discourse (ethical, political, artistic etc.). Bobbio wrote:

“The theory of argumentation refutes such too-easy antitheses. It demonstrates that between absolute truth and non-truth there exists room for truths to be subjected to constant revision, thanks to the technique of adducing reasons for and against” (Bobbio 1966, p. 322).

Bobbio’s position represents the first and most authoritative acknowledgement in Italian jurisprudence of the ‘argumentative turn’ which came about in philosophical thought following publication of Perelman’s Traité and Stephen Toulmin’s The Uses of Argument, both of which appeared in 1958 (this position was then carefully cultivated by Uberto Scarpelli)[v]. The authors of the argumentative turn evinced the weakening of the Cartesian separation between what Charles P. Snow[vi] called in those years (1959) “the two cultures”: humanistic knowledge (emotional, irrational) and scientific knowledge (neutral, rational). As recently pointed out by Adelino Cattani[vii], the term ‘argumentation’ (and its derivatives) is simply a politically correct form of the ancient term ‘rhetoric’, which is still viewed with suspicion. It serves to introduce the idea of one or more kinds of rationality distinct from the formal-demonstrative one.

What Bobbio does not explain, however, is the relation that can be established between this or these kinds of rationality and Kelsenian methodological formalism in the field of legal science. In substance, he does not tell us in what sense the “truths subjected to constant revision” are truths, and how this “revision” is performed. For formalist legal positivism, legal reasoning is a type of logical inference whose premises are authoritative in nature: the legal norms established by the legislator. Ultimately, the will of the legislator is exempt from the deductive and, therefore, logical procedure. Rationality intervenes subsequently by operating on the system of the sources. The logical control of normative statement does not necessarily have legal weight, since the value of the norm does not reside in its intrinsic or systematic consistency, but rather in the ‘fact’ that it has been legitimately promulgated. Hence, rationality and normativity are not perfectly synonymous.

On the other hand, Perelman himself believed that argumentative rationality is ‘quasi-logical’ or ‘analogous to empirical reasoning’. That is to say, it has more persuasive efficacy the more it resembles the deductive and inductive procedures, which are therefore the most certain forms of reasoning. The nouvelle réthorique must therefore be understood as the study of the factors that make a discourse persuasive: it is measured not (a priori) by the method used, but (a posteriori) by the results produced, by the ‘fact’ that it orients the audience’s judgement in a particular direction. This is a form of utilitarian empiricism that restricts argumentative theories to a subordinate level ‘weaker’ than science from the logical point of view.

I shall explain later why this point is crucial, and I shall propose a way to deal with it. What is certain is that all the authors of the argumentative turn took the same line: that rationality is ‘weak’, and that persuasion is a ‘fact’ rather than the result of a logical procedure in the proper sense.

From the 1970s onwards, ‘attempts at dialogue’ proliferated between theorists of the law tied to the analytical form of legal reasoning and the proponents of various non-formalist approaches. Perhaps the more evident of them is legal hermeneutics. According to Cattani[viii], hermeneutics, as the “art of understanding the text” (i.e. of interpretation) is “the other side of the rhetorical coin (which is instead the art of constructing the text)” (Cattani 2009, p. 23). This is therefore an argumentative theory which confronts legal positivists with the problem of decoding the prescriptive content of normative statements: for the hermeneuticists the premise of a judicial syllogism is not a given (as are definitions in the formal sciences), rather, it must be ‘found’ (Rechtsfindung) in the context of application. It is therefore necessary to illuminate interpretative processes, which are almost always implicit, in order to assess their rationality.

During the 1980s, the spread to Europe of the Hart/Dworkin debate[ix] directed attention to the question of the principles (political, ethical, social, constitutional) that should yield knowledge of the meaning of legal norms, especially for the judges that must apply them. The theme of justice thus re-entered the field of studies on law, after being excluded by the formalism of the legal positivists.

Also very influential were other philosophical and epistemological currents of thought: in particular those connected with the linguistic pragmatics introduced by the early Ludwig Wittgenstein (of the Philosophical Investigations)[x], which showed that the meaning of a normative statement necessarily depends on the context of reference and the subjects participating in the discussion. The subject thus returned to the philosophical debate, after the term ‘subjective’, as opposed to ‘objective’ (i.e. scientific), had for centuries been considered synonymous with irrationality. We may say that through these various processes of de-objectivation – which are very evident in contemporary epistemologies – the field of knowledge descended from an abstract to a concrete level.

Today, although all proponents of the analytical philosophy of law still profess legal positivism, they are prepared to admit that normative material does not constitute given premises with well-founded content. Rather, it is still raw material on which the judge works in an interpretative and ‘constructivist’ manner. Most of them no longer believe that legal reasoning can be reduced to a perfect syllogism, but instead that it is a composite and complex set of rational procedures. From this point of view, they regard argumentative theories as more or less attractive attempts to study legal interpretation[xi].

3. The argumentative turn

The opening in Italy, even if only partial, of legal positivism to the argumentative turn exhibits what I consider to be a very interesting feature: it tends to shift the legal philosopher’s attention from the field of encoded law to the activities of the judge. One might say that the ‘heroes’ of the legal sciences are no longer only the legislator, the state, and the law in the books. To a greater or lesser extent, now also of importance are the time and place in which we effectively know the norms: the domain of their application – that is the trial, which is the main semantic context of legal language.

In Italy, the scholars who have most forcefully posited the trial (and not norms) as the fulcrum of juridical experience have been Giuseppe Capograssi, Salvatore Satta and Enrico Opocher[xii]. These are authors who have tenaciously fought against formalist legal positivism, albeit from different perspectives. Capograssi and Opocher in particular, both of them legal philosophers, have adopted a perspective influenced by existentialist philosophy characterized by identification of the law as a value essential for human coexistence. The law is not neutral but has a positive axiological valence. (In truth, even a highly authoritative Italian scholar like Sergio Cotta has devoted his studies to the existential value of the law[xiii], but we cannot say that Cotta’s philosophy of law is expressly processual). Perhaps, however, it is precisely the existentialist emphasis of these philosophies that has prevented more direct and fertile contact with those scholars of legal positivism willing to consider anti-formalist accounts, like the nouvelle rhétorique or legal hermeneutics, which are less ‘compromised’ by metaphysics.

It is in this context that, since the 1970s, Francesco Cavalla[xiv], a pupil of Opocher (and in many respects Cotta) has worked at the University of Padua. Openly opposed to natural law theories, which he terms rationalist and dogmatic, Cavalla has developed an original body of thought focused on the logic of decision-making in the trial. He criticises the authors of the argumentative turn, and Perelman in particular, for lacking a rigorous theory on the rationality of argumentation. Persuasion, according to Cavalla, is not a factual (psychological, emotional) question but a methodological one. It is necessary to identify a logic of persuasion able to produce reasonings that are rationally verifiable in the same way as the results of proofs are rationally verifiable. Cavalla identifies this logic in classical thought, in authors like Plato, Aristotle, St. Augustine and, later, Cicero and Quintilian. Between the mid-1970s and the 1990s, Cavalla deepened his studies on the dialectic, the topic and rhetoric, producing numerous publications and forming a school of young scholars. In 2004 he took part in the foundation of CERMEG (Research Centre on Legal Methodology)[xv], expressly devoted to the study of judicial rhetoric, at the University of Trento.

This school of legal philosophy has innovated the field of legal studies by introducing into the analysis of legal reasoning not only the rational activities of the judge in the final stage of taking the decision, but also those of the other parties to the trial, principally the lawyers. Because the logical model is that of the dialectic, in which the reasoning begins and develops from the discourses of the parties that propound conflicting opinions, it seems incorrect to restrict verification of rationality to the decision alone. For this reason, the CERMEG has undertaken an unprecedented series of projects and experiments with lawyers’ associations.

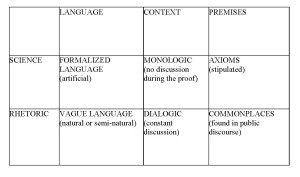

However, as I have said, although Cavalla’s account is practice-oriented, it has a solid metaphysical basis due to his studies on the notion of “principle” (Gr. arché) drawn mainly from the pre-Socratic philosophers (Thales, Parmenides, Heraclitus) and from Aristotle[xvi]. On the basis of this conception, developed by his scholars in various directions (e.g. theory of punishment, bio-law, legal epistemology, artificial intelligence and law, study of metaphors and brocards, etc.), “rhetorical truth” (and therefore trial truth) is established by a logical non-axiomatic method. The pragmatic conditions which distinguish the formation of rhetorical truth are dissimilar from those of formal and empirical procedures.

The conditions that characterize every scientific reasoning are essentially those relative to the language, the context, and the type of premises. The language of science is a language whose terms have meanings established through nominal definitions (e.g. ‘point’ or ‘number’); these meanings are never discussed during development of the proof. Finally, these meanings are conventional in nature and they are used to obtain particular practical results. A scientist, for example, can assume the (opposing) definitions of ‘light’ as an electromagnetic wave or as a corpuscle depending on the purpose of his operations. However, once one definition has been assumed, he cannot interrupt his logical operations and introduce the contrary definition.

By contrast, the rhetorician uses for his logical operations terms whose meanings are not the result of nominal definitions, but which are ‘found’ already associated with certain meanings that hold in a circumscribed space-time context x (e.g. ‘appropriate clothing’ in the context of a scientific conference may or may not include a tie, but not a tie worn around the neck without a shirt, although no formal definition on the matter has been stipulated). These terms, moreover, can be constantly disputed during the logical operation (for example, I can protest that a tie worn with a shirt but decorated with a frivolous and garish pattern is admissible as ‘appropriate’ to a scientific conference). Hence semantic fluctuation must be governed by the rhetorician, who must justify his semantic choices at every point of the logical operation. The question is: how can he/she do so?

As we know that the answer of argumentative theories is: through the forms of argumentation[xvii]. But the forms of argumentation produce persuasion: does this also mean that they produce truth? The problem becomes clear when conflicts arise among forms: what criterion obliges me to choose one form rather than another, a criterion which is not that of simple efficacy? (For this reason I previously said that argumentative theories risk being reduced to a kind of utilitarian empiricism).

If we really want to build a bridge between the “two cultures”[xviii], we must find a criterion of truth to associate with the use of the forms of argumentation. Cavalla believes that this is possible if one takes as ‘true’ every reasoning whose conclusions do not encounter logically consistent oppositions in the space-time context x in which it is developed. This logical consistency, exactly as in deductive or empirical reasoning, is governed by the principle of non-contradiction: if I have assumed premise p, I cannot reject conclusion q, regardless of whether the premise is axiomatic or non-axiomatic. The only difference consists in the fact that the conclusions obtained from axiomatic premises, being abstract, last as long as the nominal definition is accepted (and not disputed), while rhetorical conclusions must be defended whenever doubt is cast on the meanings of the terms (e.g. If p = tie, then q = appropriate; but now p = tie worn around the neck, or = decorated with a frivolous and garish pattern, so it is necessary to reformulate the meaning of ‘appropriate’ to maintain consistency between premises and conclusion). Varying the premises does not make rhetorical reasoning less logical (and verifiable) than formal reasoning: in both cases, the truth is founded on non-contradiction. This fact enables Cavalla to extend his argumentative theory into the metaphysical domain (on the base of the question: what is it that compels us to accept a non-contradictory conclusion?), but this point will not be discussed in this brief paper.

The principal features of the argumentative account proposed by the CERMEG in Italy can be summarized as follows (the s. c. “Heptalogue of CERMEG”).

1. Because the rigour of the rhetorical conclusions is guaranteed by the logical principle of non-contradiction, it has the same nature as proofs; it consists in the undeniability of the conclusions with respect to the premises;

2. Rhetorical truth is not based on a psychological ‘fact’: persuasion is the product of a logical operation (as Aristotle maintained); otherwise one must speak, not of ‘rhetoric’ but of ‘sophistry’ (persuasion without truth);

3. It is not true, as Perelman claims, that a reasoning which uses ‘probable’ premises determines solely probable conclusions: if there is consistency between conclusions and premises, the result is not ‘probable’ but ‘certain’, albeit within a particular space-time context x;

4. If this is so, there is no reason to maintain an absolute distinction between the “two cultures” (scientific and rhetorical): also rhetoric uses rational operations; also science uses argumentative forms (e.g. when it discusses the choice of premises, attributes greater or lesser authoritativeness to a scientific journal or to a team of researchers, etc.);

5. Because the premises of rhetoric are identified within concrete discursive contexts, its logical operations adhere more closely to concrete states of affairs, and are therefore particularly suited to being applied and experimented. This is especially important in politics, the economy, and the law (where decisions are taken);

6. The use of rhetorical argumentation is functional to the ‘identity of the European jurist’, because it extends its roots into the Greco-Roman conception of the rationality of the law dominant in Europe at least until the modern advent of formalist legal positivism (symmetrically with Cartesianism in philosophy);

7. For this reason, rhetorical argumentation is particularly suited to the scenarios of the Third Millennium, in that it rejects both dogmatism (which imposes the premises without allowing their discussion) and radical skepticism (which holds that the premises are of equal weight): these two approaches, in fact, consign decisions to the power of those able to impose their own opinions, while rhetoric keeps the intersubjective (ethical, political, economic, juridical) relationship open to rational discussion.

4. Possible perspectives of CERMEG’s approach

The above listed 7 features can be interpreted as the synthesis of a working program linking together various directions in the fields of metaphysics and logic, history of philosophy, epistemology, jurisprudence, theory of norms in legal procedure (civil, penal, labour, etc.), to mention only the principal ones. In all these fields different expertises could converge to check each single proposal.

The advantages of a rhetorical approach to the theory of legal argumentation especially deal with a double overtaking: on one hand, that of formalism (peculiar to all syllogistical models of legal reasoning, which are hardly enforceable to the concrete trial situation); and on the other hand that of indeterminacy (peculiar to all interpretive accounts, which excessively stress the judge’s role), being capable to enhance also the other actors of the trial (lawyers, prosecutor).

In Italy, such a working perspective is getting results in the field of legal education and training of young lawyers. Many established lawyers’ organizations ask CERMEG for arranging seminars and courses on legal methodology and for lifelong learning, and this cooperation does help in shortening the distance between academic studies and the world of practice.

The methodological formalism being largely responsible for the separation between legal theory and practice, it is also possible that the domestic activities of CERMEG could be seen as an example for other countries. Besides that, a number of shared issues between the CERMEG’s approach and the argumentative legal accounts based upon pragmatics (such as, for instance, the Pragma-Dialectical theory)[xix] or inspired by Wittgenstein’s Philophical Investigations (e. g. the Dennis Patterson’s account about the truth of legal propositions)[xx] give the chance for converging researches on the nature of legal argumentation.

NOTES

[i] See Husserl (2007).

[ii] See Hume (2010), b.III, p.I, s.I.

[iii] See Kelsen (1966).

[iv] See Perelman & Olbrechts-Tyteca (1966).

[v] See Toulmin (1969). See also Scarpelli (1976) e (1997).

[vi] See Snow (1959).

[vii] See Cattani (2009): in this essay, the authors (Cattani, Testa & Cantù) provide a brief description of the process of loss and resumption of the argumentative reasoning from the origins to the turn of 1958. After that year, they point out a renew attention for the theory and the practice of argumentation. On the same topic, are noteworthy Cattani (1994) and (2001).

[viii] Loc.ult.cit.

[ix] For a concise description of the Hart/Dworkin debate see Schiavello-Velluzzi (2005).

[x] Wittgenstein (1989).

[xi] For the Italian legal philosophy see spc. Villa (1999) (but contra see Ferrajoli (2007)).

[xii] I will confine myself to pointing out their most representative production: particularly, see Capograssi (1959-1990), Satta (1994), Opocher (1966) (1983), Cotta (1979) (1981). For a more detailed description of this approach based on trial, see Cavalla (1991).

[xiii] See Cotta (1991) .

[xiv] For a complete outline of the perspective of studies devoloped under the mastership of Francesco Cavalla concerning the argumentative topic, see Cavalla (1983) (1984) (1991) (1992) (1996) (1998) (2004) (2006) (2007), Fuselli (2008), Manzin (2004) (2006) (2008) (2008a) (2008b) (2010), Manzin & Sommaggio (2006), Manzin & Puppo (2008), Moro (2001), Puppo (2006) (2009).

[xv] For further information, see the web site www.cermeg.it.

[xvi] I am mainly referring to Cavalla (1996).

[xvii] Cf. Patterson (2010) and Manzin (2010).

[xviii] Cf. Snow (1959).

[xix] See van Eemeren & Grootendorst (2004), van Eemeren (2010).

[xx] See Patterson (2010).

REFERENCES

Cattani, A. (1994). Forme dell’argomentare. Padova: GB.

Cattani, A. (2001), Botta e risposta. L’arte della replica. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Cattani, A., Cantù, P., Testa, I. & Vidali, P. (Eds) (2009). La svolta argomentativa. Napoli: Loffredo.

Bobbio, N. (1966). Prefazione. In C. Perelman & L. Olbrechts-Tyteca, Trattato dell’argomentazione: la nuova retorica. Torino: Einaudi.

Capograssi, G. (1959-1990). Opere. Milano: Giuffrè.

Cavalla, F. (1983). Della possibilità di fondare la logica giudiziaria sulla struttura del principio di non contraddizione. Saggio introduttivo. Verifiche 1, 5-38.

Cavalla, F. (1984). A proposito della ricerca della verità nel processo. Verifiche 4, 469-514.

Cavalla, F. (1991). La prospettiva processuale del diritto. Saggio sul pensiero filosofico di Enrico Opocher. Padova: Cedam.

Cavalla, F. (1992). Topica giuridica. Enciclopedia del diritto XLIV, 720-739.

Cavalla, F. (1996). La verità dimenticata. Attualità dei presocratici dopo la secolarizzazione. Padova: Cedam.

Cavalla, F. (1998). Il controllo razionale tra logica, dialettica e retorica. In M. Basciu (Ed.), Diritto penale, controllo di razionalità e garanzie del cittadino. Atti del XX Congresso Nazionale della Società Italiana di Filosofia Giuridica e Politica (pp. 21-53). Padova: Cedam.

Cavalla, F. (2004). Dalla “retorica della persuasione” alla “retorica degli argomenti”. Per una fondazione logico rigorosa della topica giudiziale. In G. Ferrari & M. Manzin (Eds.), La retorica fra scienza e professione legale. Questioni di metodo (pp. 25-82). Milano: Giuffrè.

Cavalla, F. (2006). Logica giuridica. Enciclopedia filosofica 7, 6635-6638.

Cavalla, F. (2007). Retorica giudiziale, logica e verità. In F. Cavalla (Ed.), Retorica processo verità. Principi di filosofia forense (pp. 17-84). Milano: Franco Angeli.

Cotta, S. (1979). Perché il diritto. Brescia: La Scuola.

Cotta, S. (1981). Giustificazione e obbligatorietà delle norme. Milano: Giuffrè.

Cotta, S. (1991). Il diritto nell’esistenza: linee di ontofenomenologia giuridica. Milano: Giuffrè.

Eemeren, F.H. van (2010). Strategic Maneuvering in Argumentative Discourse: Extending the Pragma-Dialectical Theory of Argumentation. Amsterdam-Philadelphia: Benjamins.

Eemeren, F.H. van, & Grootendorst, R. (2004). A Systematic Theory of Argumentation: The Pragma-Dialectical Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ferrajoli, L. (2007). Principia iuris: Teoria del diritto e della democrazia. Roma-Bari: Laterza.

Hume, D. (2010). A Treatise of Human Nature. Retrieved from <http://www.gutenberg.org/files/4705/4705-h/4705-h.htm#2H_4_0101>

Husserl, E. (2007). Die Krisis der europäischen Wissenschaften und die transzendentale Phänomenologie: Eine Einleitung in die phänomenologische Philosophie. Hamburg: Meiner.

Kelsen, H. (1966). La dottrina pura del diritto. Torino: Einaudi.

Manzin, M. (2004). Ripensando Perelman: dopo e oltre la «nouvelle rhétorique». In G. Ferrari & M. Manzin (Eds.), La retorica fra scienza e professione legale. Questioni di metodo (pp. 17-22), Milano: Giuffrè.

Manzin, M. (2006). Justice, Argumentation and Truth in Legal Reasoning. In Memory of Enrico Opocher (1914-2004). In M. Manzin & P. Sommaggio (Eds.), Interpretazione giuridica e retorica forense: il problema della vaghezza del linguaggio nella ricerca della verità processuale (pp. 163-174), Milano: Giuffrè.

Manzin, M., & Sommaggio, P. (Eds.) (2006). Interpretazione giuridica e retorica forense: il problema della vaghezza del linguaggio nella ricerca della verità processuale. Milano: Giuffrè.

Manzin, M. (2008a). Ordo Iuris. La nascita del pensiero sistematico. Milano: Franco Angeli.

Manzin, M. (2008b). Del contraddittorio come principio e come metodo/On the adversarial system as a principle and as a method. In M. Manzin & F. Puppo (Eds.), Audiatur et altera pars. Il contraddittorio fra principio e regola/ Audiatur et altera pars. The due process between principles and rules (pp. 3-21). Milano: Giuffrè.

Manzin, M., & Puppo, F. (Eds.) (2008). Audiatur et altera pars. Il contraddittorio fra principio e regola/ Audiatur et altera pars. The due process between principles and rules. Milano: Giuffrè.

Manzin, M. (2010). La verità retorica del diritto. In D. Patterson, Diritto e verità, tr. M. Manzin (pp. IX-LI). Milano: Giuffrè.

Moro, P. (2001). La via della giustizia. Il fondamento dialettico del processo. Pordenone: Libreria Al Segno.

Moro, P. (2004). Fondamenti di retorica forense. Teoria e metodo della scrittura difensiva.Pordenone: Libreria Al Segno.

Opocher, E. (1966). Giustizia.Milano: Giuffrè.

Opocher, E. (1983). Lezioni di filosofia del diritto.Padova: Cedam.

Patterson, D. (2010). Diritto e verità. (M. Manzin, Trans.). Milano: Giuffrè. (Original work published 1996). [Italian translation of Law and Truth].

Perelman, C., & Olbrechts-Tyteca, L. (1966). Trattato dell’argomentazione. La nuova retorica. (C. Schick, M. Mayer & E. Barassi, Trans.). Torino: Einaudi. (Original work published 1958). [Italian translation of Traité de l’argumentation. La nouvelle rhétorique].

Puppo, F. (2006). Per un possibile confronto fra logica fuzzy e teorie dell’argomentazione. RIFD. Rivista Internazionale di Filosofia del Diritto 2, 221-271.

Puppo, F. (2010). Logica fuzzy e diritto penale nel pensiero di Mireille Delmas-Marty. Criminalia 2009, 631-656.

Satta, S. (1994). Il mistero del processo. Milano: Adelphi.

Scarpelli, U. (1997). Cos’è il positivismo giuridico. Napoli: ESI.

Scarpelli, U. (1976). Diritto e analisi del linguaggio. Milano: Comunità.

Schiavello, A., & Velluzzi, V. (2005). Il positivismo giuridico contemporaneo. Torino: Giappichelli.

Snow, C.P. (1959). The Two Cultures and a Second Look. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Toulmin S.E. (1958). The Uses of Argument. London: Cambridge University Press.

Villa, V. (1999). Costruttivismo e teorie del diritto. Torino: Giappichelli.

Wittgenstein, L. (1989). Philosophical investigations. Oxford: Blackwell.