ISSA Proceedings 2010 – Visual Argumentation. A Reappraisal

Visual argumentation is an incipient field in the broad domain of argumentation. Its existence has been well documented, thanks to the efforts of a few scholars, amongst whom I would like to mention Leo Groarke (Birdsell and Groarke 1996; Birdsell and Groarke 2006). Interestingly, two sessions were devoted to visual argumentation in the ISSA 2010 Congress, with 10 speakers, which is not so bad for a young field! Once admitted – even if not by all theorists of argumentation – that visual argumentation exists, it seems to me necessary at this stage of its development to reassess its definition [i].

Indeed, the first step was to give it legitimacy. This was done by giving many examples, most of them convincing, of visual arguments. Basically the task was to show that the verbal is not the only way of arguing: the stimulating discovery was that many verbal arguments can be translated visually or that an equivalent to verbal argument can be found in images. The first battle, therefore, was to gain legitimacy. Once it has been won, the problem, at least this is the way I see it, is not to go on accumulating more evidence of the existence of visual argumentation, but instead to discuss its definition and extension.

For my part, I am convinced that there are visual arguments, and I have advocated elsewhere in favor of them (Roque 2004). However, I feel uncomfortable with the definitions given to it, as well as with the way its relationship to verbal argumentation is generally understood. So, the main issue I would like to raise is the definition of visual argumentation, and the second one is its relationship to verbal argumentation, which I will examine through the complex issue of mixed media, that is, when argumentation is both verbal and visual.

1. Definition

Let us start with the definition. What is visual argumentation? Surprisingly, I did not find much discussion of it in the literature, perhaps because advocates of visual argumentation take it for granted that visual argumentation exists. However, an argument by example is not sufficient to assess a field. In fact, discussions on this topic are usually initiated by people who deny the existence of visual arguments. Indeed, within the field we often use the expression “visual argument” or “visual argumentation”, which is very practical. However, one might consider that in so doing, we are begging the question, when on the contrary the existence of visual arguments is what we should be showing.

For this reason, I would like to briefly summarize the wide range of definitions explicitly or implicitly given to visual arguments, without discussing each one in detail, as my overriding aim is to propose a rough classification of these definitions.

Yet, one could reply that the definition of ‘visual argument’ is so obvious that it does not require much discussion: a visual argument is an argument expressed visually. According to Birdsell and Groarke, “we understand visual arguments to be arguments (in the traditional premise and conclusion sense) which are conveyed in images” (Birdsell and Groake 2006, p. 103). And according to Blair, visual arguments are arguments “expressed visually, for example by paintings and drawings, photographs, sculpture, film or video images, cartoons, animations, or computer-designed visuals” (Blair 1996, p. 26).

These definitions have two components; the first is “argument” and the second “visually”. Even if the meaning of “visual argument” may seem obvious, this is not the case for me, for it can be understood in many different ways. Indeed, when we talk about “visual argument” or “visual argumentation”, what does this expression say about the kind of relationship between argument or argumentation and the visual? Let us look first at the “argument” component of the definition.

1.1. Argument

a) In a restrictive way, we can consider that an argument is verbal in nature, hence that the visual would be a mere illustration, or a “visual flag”[ii]. In this case, the argument is not visual. I will come back to this issue later.

b) The opposite opinion consists in taking the visual more seriously and accordingly considers that the argument itself is visual, or in other words, that the argument is structured through a visual syntax. Now, the way we understand how the structure of an argument works visually depends on the conception of argument we favor. This is of course a huge and slippery issue in so far as there is no consensus on what an argument is or should be.

If we define argumentation as “an exchange of arguments between two speech partners reasoning together in turn-making sequences aimed at a collective goal” (Walton 1998, p. 30), the visual would be excluded from the realm of argumentation. Fortunately, other broader definitions allow us to take into account the possibility of arguing visually. For instance, according to Blair, “Visual arguments are to be understood as propositional arguments in which the propositions and their argumentative function and roles are expressed visually” (Blair 1996, p. 26). In this case, the visual is not a mere illustration of a verbal argument, since it contains propositions organized and structured argumentatively. Likewise, a visual argument has also been considered as “a concatenation of visual statements in a particular image [that] can […] function as reasons for a conclusion” (Groarke 1996, p. 111).

These conceptions raise complex issues that are beyond the scope of this paper, in particular determining to what extent we can consider that an image contains “propositions”. Another problem is that, if we conceive of argument in the sense of a premise-conclusion structure, we need to find at least two propositions or rather “utterances”[iii] within an image in order for it to convey an argument. However, many images do not fit this scheme, as they contain only one “utterance”.

c) When faced with this problem, various solutions can be found. One is to consider a visual “utterance” as an enthymeme, understood as a truncated syllogism in which one of the premises or the conclusion is missing, or rather is not explicit (Smith 2007; Nettel 2005). However, in visual arguments reduced to one utterance, both a premise and the conclusion are missing. Therefore another solution is to choose a broader definition of argument, without reference to the syllogistic scheme. For example, if we consider that an argument consists of a claim plus reasons given to support this claim, an image containing a single utterance can match this definition when it presents a standpoint and gives reasons for supporting this standpoint (Blair 2004, p. 44).

d) A last distinction has been made. Some authors consider that an image may present features of an argument, but that its function is different: given the narrow relation between images and pathos, they think that the function of an image is more persuasive than argumentative (for references, see Roque 2004, p. 102-106). Even scholars favorable to visual argumentation consider that a “visual argument is one type of visual persuasion” (Blair 2004, p. 49). Here again, I merely mention this wide issue without discussing it in more detail, as I simply want to give an overview of the definitions of the field.

1.2. Visual

Let us now turn towards the definition of the second component of the “visual argument”: the “visual”. At first sight, it is so obvious that it seems to be beyond discussion: if a visual argument is not an argument expressed visually, what could it be? However, this is exactly what I would like to question, for it obviously depends on what we consider to be the “visual”. Now, it seems to me that when we speak about a visual argument, in order to distinguish it from a (verbal) argument, we usually emphasize the channel of transmission. The visual, then, at least understood this way, is a channel. However, the channel alone is not sufficient for defining a kind of argumentation. In a similar way, semioticians have put into question the relevance of the criterion of the channel in semiotics: indeed, the classification of signs according to their channels of transmission rests on the substance of the expression, and this criterion is not relevant to the definition of semiotics, which is above all a form, not a substance, according to Hjelmslev (Groupe µ 1992, p. 58).

Yet there is another way of understanding the “visual”: not as a channel, but as a code, that is a set of rules that make it possible to give meaning to the elements of a message (Klinkenberg 2000, p. 49). And here again, the visual is opposed to the verbal, this time as different codes. But whatever the way “visual” is understood, it is not satisfying. The channel alone is not sufficient for a definition of argumentation, since the same argumentation can use two different channels: if I read a text for myself, it passes through the visual channel; and if I read the same text to someone, it also passes through the auditory channel. Furthermore, and conversely, the same channel can transmit different codes: for instance, chromatic codes, iconic codes, written signs, and so on, can all be conveyed through the visual channel.

Nor on the other hand, is the visual code alone sufficient to define visual argumentation accurately. Indeed, when emphasizing the visual code (as opposed to the verbal), we suppose that a visual argument is only conveyed by an image. This is how the two definitions given above can be understood: visual arguments are arguments conveyed in images or visual arguments are arguments expressed visually. The trouble, however, is that most of the time a visual argument is not purely visual, but also contains verbal elements. In other words, except for isolated cases, a visual argument is composed of both a visual and a verbal code, as in advertising and political posters. It is a case of a multi-code system. In order to take these elements into account, I would suggest modifying the existing definitions of visual arguments and propose instead the following: a visual argument is an argument conveyed through the visual channel and sometimes using the visual code alone, but most of the time both verbal and visual codes combined within the same message. The fact that most messages conveying visual arguments are mixed codes has important consequences that have often been overlooked. I will come back to this issue in the second part of my paper.

Yet, every channel and every code has properties and specific constraints that need to be taken into account since they have consequences on the way the argument is transmitted (Groupe µ 1992, p. 58 – 59; Klinkenberg 2000, p. 47 – 48). From this point of view, the constraints of the channel and the properties of the codes are crucial, as it is not the same to transmit an argument verbally as to transmit one visually. To end with this point: we must keep in mind that when we talk about “visual arguments”, at times “visual” refers to the channel, and at others to the visual code. It is therefore very important to avoid as far as possible this ambiguity and clarify in which sense we are using the word “visual”. I hope to have contributed to a clarification of this point.

1.3. Argument & Visual

To go further, we now need to analyze the relationship between “argument” and “visual” in a visual argument. The issue is whether, in a visual argument, the argument itself is visual, or whether the argument is in fact verbal and just expressed visually. The answer to this question is important for it raises, again, the issue of the nature of arguments, in particular whether or not an argument is verbal in nature.

If I insist on this point, it is because it seems crucial to me to dissociate argumentation and the verbal. As long as we conceive of argumentation as verbal by nature, it will be difficult, if not impossible, to find room for visual argumentation, because of the hegemonic position the verbal has in argumentation theory and practice. For this reason, as I have argued in the previous section, defining visual argumentation as an argument expressed visually is not sufficient. Indeed, it leaves unresolved the issue of whether or not an argument, a verbal argument, I mean, could be translated, transposed, transformed into a visual argument (Roque 2010). To make the dissymmetry between the verbal and the visual more obvious, I would say that an argument is never defined as an argument expressed verbally. So why should we have to define the visual by its channel of transmission, or by the visual code, if not because it would be a derived form of argument, translated and detached from the standard verbal argument?

In a previous paper on a similar topic, I wondered what was visual in visual argumentation. My answer was that what is properly visual in a visual argument is not necessarily the argument itself, but the way it is visually displayed (Roque 2010). The hypothesis underlying this claim is that most of the time arguments are a set of mental or logical or cognitive operations independent from the verbal, so that they can be expressed verbally as well as visually. Seen this way, a visual argument is just such an argument expressed visually. In other words, therefore, it is not the argument itself that could be considered visual, but the way it is displayed.

This last point is crucial, in my opinion, for the definition of visual argumentation. When we say that a visual argument is just an argument “expressed visually”, or “conveyed in images”, first, we implicitly admit or rather concede that such an argument moves away from its standard verbal presentation. And second, we tend to consider that the operation of expressing or conveying or transmitting the argument is a neutral one, when on the contrary an important part of visual argumentation consists in the syntactic operations that take into account the specificity of visual language.

This leads to the following issue: to what extent is an argument displayed visually different from the same argument presented verbally? I would say that it depends on the kind of argument at stake.

1.3.1. Arguments expressed either verbally or visually

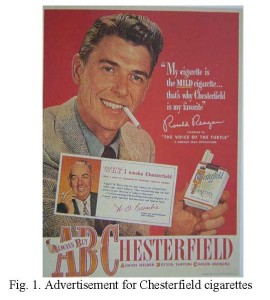

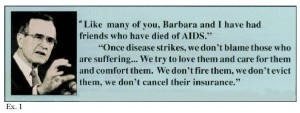

It seems to me that in some cases at least, no hierarchy can be established between an argument expressed verbally or visually. This is the case, for instance, of the argument from authority as shown in fig. 1.

In this advertisement, Chesterfield cigarettes use a famous actor, Ronald Reagan, as an argument from authority to promote their brand. There is a strict parallel here between the same argument in a written form, a quotation from Reagan authenticated by his signature, and in a visual form, showing his smiling face, a cigarette wedged between his lips, and his left hand presenting a pack of this brand.[iv] The two codes, the verbal and the visual, are parallel and reinforce each other. In an example like this, if we ask what argument is at stake, it does not make sense to claim that the argument itself is visual. Nor does it make sense to hold that the argument is verbal and translated visually. The nature of the argument here is neither verbal nor visual. It is an argument from authority expressed through a double code.

Now, arguing that in this case the argument itself is not visual is not to deny the importance of the visual. On the contrary, my argumentative strategy here is to break the hierarchy between the verbal and the visual. Showing that in some cases at least an argument, such as an argument from authority, can be expressed visually or verbally, greatly helps to consolidate the place of the visual within argumentation theory and practice. Indeed, when showing this, we dislodge the verbal from its pretense to hegemony, since the same argument expressed visually would not represent a deteriorated and therefore suspicious use of a verbal argument. No, it deserves to be considered as a fully-fledged argument, as suitable as its verbal counterpart.

1.3.2. Arguments better expressed visually

Now, I said that some arguments can be expressed both visually and verbally without substantive changes: the differences are due to the constraints of the visual channel and the properties of the codes. This is mainly the case for arguments based on logical operations (like arguments from cause or consequence). Yet, in other cases, such as arguments by analogy, the arguments are much better displayed visually than verbally. The reason is that the main feature of the visual is simultaneity: an image enables us to grasp at the same time several elements simultaneously present in the same visual space. As Gombrich noted, “the family tree demonstrates the advantages of the visual diagram to perfection” (Gombrich 1982, p. 149). This is, I think, the main difference from the verbal, which is linear, successive, just like a string (Arnheim 1969, p. 246). The linearity of the verbal is of course very helpful for argumentation in general, in the sense of uttering a chain of propositions which string the concepts into a logical sequence, but it is unpractical for purposes of making explicit an analogy, while this is one of the best qualities of the visual (Arnheim 1969, p. 55). From this point of view, it seems to me that an argument by analogy is definitely much stronger when the similarity on which it rests is presented visually. This is in particular the case with diagrams. If we conceive of a diagram, as suggested by Nelson Goodman, as a kind of picture in which “the only relevant features […] are the ordinate and abscissa of each of the points the center of the line passes through” (Goodman 1976, p. 229), then a visual presentation of an argument based on a similarity between two diagrams is more effective than the verbal presentation of the same argument.

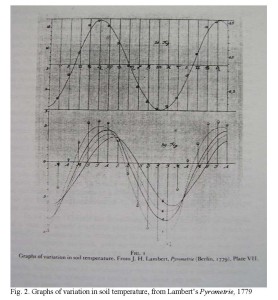

Let me give an example. If I say that the temperature of the soil follows a regular cycle from January to December, which can be shown if we compare the temperature of the surface and that of a deeper layer, or if we compare it in different latitudes, my discourse does not have the same argumentative effectiveness as its visual presentation. Consider Lambert’s 1779 Pyrometrie (fig. 2), one of the first uses of a graph, in which the temperatures are shown on the ordinate and time on the abscissa.

We see, at the bottom of the graph, the modifications of amplitude of the curve in function of different depths of temperature measurement. Above that, we find the average temperature of the soil in different latitudes. These diagrams fascinated the scientists of the time, for they provided an excellent visual argument, showing clearly the regularity of a phenomenon in spite of the modifications of depth and latitude. As Jakobson noted, “In such a typical diagram as statistical curves, the signans presents an iconic analogy with the signatum as to the relations of their parts” (Jakobson 1971, p. 350). This explains how these diagrams can fulfill not only a rhetorical but also an argumentative function (see also Kostelnick 2004, p. 226-234).

The impact of an argument based on visual analogy is not limited to science. We also find it frequently in advertising and political posters.

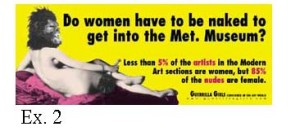

In an anti-war poster (fig. 3), the graphic designer used a strong analogy between a grenade and the Earth to warn us against the dangers of war that could lead to the explosion of the Earth. It is an example of what Perelman calls “metaphoric fusion” (Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca 1970, p. 538). Since it moves the two domains of the analogy closer, this fusion “facilitates the realization of argumentative effects” (Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca 1970, p. 536). The same authors also note that satirical designers often use this metaphorical fusion of the two fields into one, creating strange beings or objects (Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca 1970, p. 540). Indeed the plasticity and simultaneity of the visual code is a fantastic tool for condensing an analogy in a heterogeneous shape that borrows some of its features from the two domains concerned by the analogy. This iconic feature which semioticians call “interpenetration” (Groupe µ 1992, p. 274) is much more appealing than its verbal counterpart. Showing a grenade-Earth is indeed more effective than just explaining that in the same way as a grenade can explode, so can the Earth if we do not put an end to war.

2. Classification

Since most frequently visual argumentation takes place alongside verbal argumentation, it is crucial to clarify how the verbal and the visual work together in mixed media, that is, when argumentation is both visual and verbal. Indeed, the problem is that, due to the hegemony of verbal argumentation, most scholars, even those favorable to visual argumentation, continue to assume that in the case of mixed media, the argumentation is above all verbal, so that the visual plays a minor role (Adam and Bonhomme 2005, p. 194 and 217). This widespread opinion has dramatic consequences, in particular the fact that the part the visual can play is neglected. For this reason, it seems to me urgent to provide a classification of the different kinds of relationships between the visual and the verbal in mixed media argumentation.

So let me propose such a provisional classification, which I will attempt to roughly sketch out in what follows:

– The first category is what Groarke (2002, p. 140) calls a “visual flag”, when an image attracts attention to an argument presented verbally. It corresponds to the first phase of the old principle of advertising communication known as AIDA (attract Attention, maintain Interest, create Desire, and get Action) (Chabrol and Radu 2008, p. 22).

However, as Groarke and Tindale (2008, p. 64) rightly note, “In cases like this, the non-verbal cue that catches our eye is only a flag and not itself an argument or part of an argument, for the flag is not used to convey the message of the argument and only functions as a means of directing us to the text that conveys the actual argument”.

It is important to recognize the existence of visual flags, because it is true that many messages work in this way, but more importantly, because we have to separate them from other categories, in order not to confuse the part for the whole. What I mean is that for many scholars the visual flag is the general model of the relationship between visual and verbal in mixed media, as they consider that an image is unable to convey an argument by itself and can, at most, attract attention to a verbal argument. Even for an art historian like Gombrich, “the visual image is supreme in its capacity for arousal” (Gombrich 1982, p. 138). Precisely for this reason it is important to distinguish the visual flag from other possible relationships between text and image in mixed media.

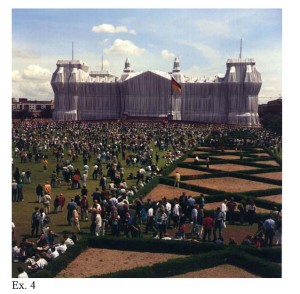

– Indeed, another category can be identified when the visual and the verbal present parallel argumentations in which both contribute to the general meaning of the mixed work. In cases like this, there is no hierarchy between the visual and the verbal. Both present an argument, and it may happen that the verbal and the visual arguments belong to the same kind of argument. Their function is redundant, as is usual in a communication process. This is particularly the case with arguments based on logical operations (cause, consequence). I would like to demonstrate the point by giving two examples:

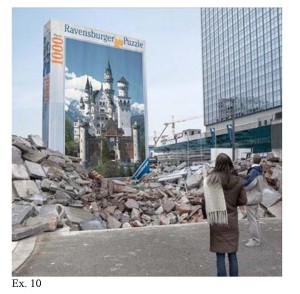

In a series of engravings, which are considered as the first anti-war images

Fig. 4. Jacques Callot, Miseries and Disasters of War, 1633, engraving

Ceux que Mars entretuent de ses actes méchants/Accommodent ainsi les pauvres gens des champs /Ils les font prisonniers ils brûlent leurs villages/Et sur le bétail même exercent des ravages, / Sans que la peur des Lois non plus que le devoir/ Ni les pleurs et les cris les puissent émouvoir.

(fig. 4), Jacques Callot uses a strict parallel between words and images. Both show the disastrous consequences of war and can be considered therefore as what Perelman calls a pragmatic argument, which “makes it possible to appreciate an act or an event according to its favorable or unfavorable consequences” (Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca 1970, p. 358). The text describes and the image depicts. Hence their parallel and redundant function. In this case there is no explicit conclusion, either verbal or visual. However, insisting on the terrible consequences of the behavior of soldiers during a war is an argument against war.

The second example is the advertisement for Chesterfield cigarettes analyzed above (see fig. 1): the argument is the same (argument of authority) and uses the same “authority” (Ronald Reagan); it is displayed verbally (through a quotation) and visually (through a photograph). Here, too, there is redundancy between the two codes.

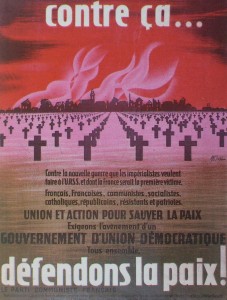

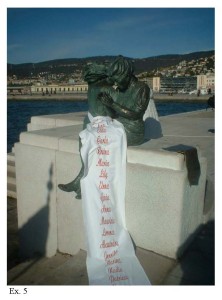

– A third category should be distinguished, when the argument is constructed using visual and verbal elements. In cases like this, that I propose to call “joint argument”, the visual and the verbal are closely intertwined in the making of the argument with a contribution from each. Mostly, the conclusion is given by the text. In an anti-war poster (fig. 5), the syntactic articulation between the verbal and the visual is given by the deictic “That” which refers to the image. The structure, then, is not a parallel between the verbal and visual codes, but a syntactic interaction between them thanks to a connector (Klinkenberg 2000, p. 235-36). In this case, the connector is verbal, and serves to articulate text and image. Now in this poster, the visual plays a central role in the construction of the argument. If we examine the relation between text and image, we can see that the poster is divided into two parts: the upper part contains the image and the text “Against that…” referring to the image, while the bottom part contains only text. This long text reads:

Against the new war Imperialists want to wage on the USSR and whose first victim would be France, Frenchmen, Frenchwomen, Communists, Socialists, Catholics, Republicans, Resistance fighters and Patriots,

UNION AND ACTION TO SAVE PEACE

Let’s demand the installation of a GOVERNMENT OF DEMOCRATIC UNION

All together,

LET US DEFEND PEACE!

This text contains no argument; it just draws the conclusion that we have to defend peace; its starting point is an opposition to war. However, no argument is given verbally to explain why we need to be opposed to war. The reason is that the premise that contains the argument is given visually: in the image we can identify again, as very often in anti-war posters, a pragmatic argument showing the bad consequences of war: in particular a village burning and a huge graveyard full of war victims. Let us note that in this and many other similar cases, the image therefore plays a central role in structuring the joint argument. This also shows that in mixed media argumentation, it is not true that the argumentation is mainly verbal and the image relegated to a mere illustration or flag.

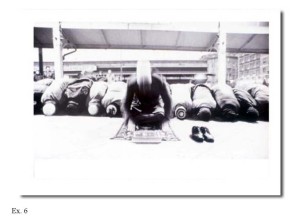

– Lastly, the argument may be constructed through an opposition between the verbal and the visual. This is often the case, for a reason related to a particular feature of images: the fact that it is hard to use an image for the purpose of negation (except in codified interdiction signs when the picture showing the forbidden action is crossed out by a graphic mark; see Roque 2008, p. 187-88). Because of this characteristic, the visual and the verbal often combine their properties: the visual is used in order to describe the situation we reject; and the verbal in order to make this rejection explicit.

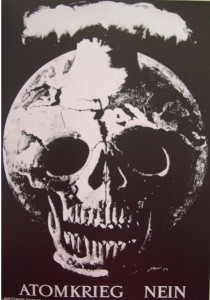

In fig. 6, we are very far from the visual flag we commented on earlier, since we cannot say that the argument is verbal: the verbal just gives a name to the issue at stake, “nuclear war”, and adds its opposition to it: “No”. We might consider the “no” here as the conclusion of the argument. However, no reason is provided verbally to support the opposition to nuclear war, for it is given visually. Hence the crucial role of the visual in the argument. First of all, let us note that there is a redundancy between the verbal and the visual, as both are about nuclear war, expressed verbally in the text and visually through the “atomic mushroom cloud”. Now, the pivotal role of the visual in the argument comes from a plastic device, which is specific to the visual: its ability to fuse two different shapes and suggest accordingly their similarity, here the shape of the Earth and that of a skull. It is the same “metaphorical fusion”, or rather interpenetration we saw in fig. 3. In this poster, the Earth-skull (a device sometimes considered as a visual metaphor), contains different arguments. The first is once more the pragmatic argument, so frequent in anti-war posters, showing that in case of nuclear war, there will be no more life on Earth. The second is an argument by analogy: if nuclear war breaks out, the Earth will look like a skull. This analogy is of course reinforced by the features common to Earth and skull, namely their rounded shape. We can also consider that the argument is structured through an antithesis between the verbal and the visual, with the visual showing the consequences of nuclear war, and the text calling for a rejection of it.

By way of conclusion, I would say that it seems to me it is now time to initiate a broad discussion amongst those of us working in visual argumentation about the definition of the field. So as to provoke such a discussion, I have tried, in the foregoing remarks, to clarify somewhat the complex relation between the notions “argument” and “visual” in the definition of visual argumentation, which has led me to distinguish several categories. Finally, insofar as the most common situation is that of mixed media, both verbal and visual, I proposed a classification based on the part played by each in such mixed media arguments. I hope that my suggestions will contribute to a general debate that seems to me necessary at this stage in the development of visual argumentation.

NOTES

[i] I would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers as well as Ana Laura Nettel; their comments have greatly helped me to improve a previous version of this paper.

[ii] The term was coined by Groarke 2002, p. 140.

[iii] It is beyond the scope of this paper to examine why I prefer to speak of visual utterances instead of visual propositions. For the meaning of “utterance” (“énoncé” in French) see Ducrot 1980, pp. 7-18.

[iv] The fact that we can identify an ad verecundiam here instead of an argument of authority, since Reagan is not an expert in matters of cigarettes, does not change my point which is about the part played by the verbal and the visual in the argument.

REFERENCES

Adam, J.-M. and Bonhomme, M. (2005). L’Argumentation publicitaire: Rhétorique de l’éloge et de la persuasion. Paris: Armand Colin.

Arnheim, R. (1969). Visual Thinking. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press.

Birdsell, D. S. & Groarke L. (1996). Toward a Theory of Visual Argument. Argumentation and Advocacy 33-1, 1-10.

Birdsell, D. S. & Groarke L. (2006). Outlines of a Theory of Visual Argument. Argumentation and Advocacy 43, 103-113.

Blair, T. (1996). The Possibility and Actuality of Visual Arguments. Argumentation and Advocacy 33-1, 23-39.

Blair, T. (2004). The Rhetoric of Visual Arguments. In C. A. Hill and M. Helmers (Eds.), Defining Visual Rhetorics (pp. 41-61), Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Chabrol, C. & Radu, M. (2008). Psychologie de la communication et persuasion: Théories et applications. Brussels: De Boeck.

Ducrot, O. et al. (1980). Les mots du discours. Paris: Minuit.

Gombrich, E. (1982). The Image and the Eye: Further Studies in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation. Oxford: Phaidon.

Goodman, N. (1976). Languages of art: An Approach to a Theory of Symbols. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company.

Groarke, L. & Tindale, C. W. (2008). Good Reasoning Matters !: A Constructive Approach to Critical Thinking. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Groarke, L. (1996). Logic, Art and Argument. Informal Logic 18, 105-129.

Groarke, L. (2002). Toward a Pragma-Dialectics of Visual Argument. In F. H. van Eemeren (Ed.), Advances in Pragma-Dialectics (pp. 137-151), Amsterdam: Sic Sat.

Groupe µ (1992). Traité du signe visuel: Pour une rhétorique de l’image. Paris: Seuil.

Klinkenberg, J.-M. (2000). Précis de sémiotique générale. Paris: Seuil.

Kostelnick, C. (2004). Melting-Pot Ideology, Modernist Aesthetics, and the Emergence of Graphical Conventions: The Statistical Atlases of the United States, 1874-1925. In C. A Hill and M. Helmers (Eds.), Defining Visual Rhetorics (pp. 215-242), Mahwah, N.J.: Laurence Erlbaum.

Jakobson, R. (1971). Quest for the essence of language. In R. Jakobson, Selected writings: Words and language. S. Rudy (Ed.), Vol. 2 (pp. 345-359). The Hague, Paris: Mouton.

Nettel, A.-L. (2005). The Power of Image and the Image of Power: the Case of Law. Word and Image 21-2, 137-150.

Perelman, C. and Olbrechts-Tyteca, L. (1970). Traité de l’argumentation: La nouvelle rhétorique. Brussels: Edition de l’Institut de Sociologie Université Libre de Bruxelles.

Roque, G. (2004). Prolégomènes à l’analyse de l’argumentation visuelle. In E. C. Oliveira (Ed.), Chaïm Perelman. Direito, Retórica e Teoria da Argumentação (pp. 95-114), Feira de Santana (Brazil): Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana.

Roque, G. (2008). Political Rhetoric in Visual Images. In E. Weigand (Ed.), Dialogue and Rhetoric (pp. 185-193), Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Roque, G. (2010). What is Visual in Visual Argumentation? In J. Ritola (Ed.), Arguments Cultures, Proceedings of OSSA 09, CD-ROM (pp. 1-9), Ontario, Canada: Ontario Society for the Study of Argumentation, University of Windsor.

Smith, V. J. (2007). Aristotle’s Classical Enthymeme and the Visual Argumentation of the Twenty-First Century. Argumentation and Advocacy 43, 114-123.

Toulmin, S. (1958). The Uses of Argument. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Walton, D. (1998). The New Dialectic: Conversational Contexts of Arguments. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.