ISSA Proceedings 2010 – Adaptation To Adjudication Styles In Debates And Debate Education

1. Introduction

1. Introduction

Academic discussion over debate adjudication paradigms gained enthusiasm in 80s and early 90s. Main contributors were in the U.S. and the discussion was based on how collegiate debate tournaments were run and judged at NDT, CEDA and others sharing the same (or at least similar) format(s) with months of research and preparation for a topic and adjudicator pool (Prepared Debate Contests). Japanese debating community then was with similar debate formats and introduced the theories developed there. Now after almost two decades from then, the number and size of international tournaments have grown. Major international tournaments are with impromptu topics and had been with a separated adjudication pool till recent (Impromptu Debate Contests). Analysis on the adjudication paradigm of the later community is a necessary update not only for participating students who wish to learn debating in both paradigms but especially for researchers who hope to analyze how audience evaluate arguments. As Zarefsky wrote, if the starting point of analysis were the contest debate then the inquiry into paradigms would be trivialized (Zarefsky, 1982, p.141). Analysis on how the adjudication paradigm affects the decision by audience and its repercussion to the argumentation of speakers stays significant in shaping better rules for substantial debates happening everyday in the society.

This paper[i] first applies the theories and terms used in the discussion on debate paradigms in 1980s and 1990s to explain how adjudication is done at international tournaments nowadays. Then we elaborate the difference in adjudication between two distinctive debate communities. Lastly, we examine how students shift and adjust their speeches according to the new adjudication style to them and how the difference of adjudication style influences educational effect of debating programs.

2. Adjudication Paradigms

There are roughly three kinds of debate i.e. Truth Seeking Debate, Trophy Seeking Debate and Future Seeking Debate.

Truth Seeking Debate can be divided to two. One seeks permanent truth while another only pursues temporal truth. Stock Issue Paradigm belongs to the first category and Hypothesis Testing Paradigm and Advocacy Paradigm for the later. Participants of former group are often described with court analogies while those of later often see themselves as scientists or scholars (Ulrich, 1984, Ulrich, 1986 & Izuta, 1985).

Paradigm of trophy seeking debate here are for example “the debate judge as debate judge” paradigm suggested by Rowland (Rowland, 1984) and game paradigm suggested by Snider (Snider, 1984). For them, a debate is nothing more than a game (admissibly games can be educational for the competitors) and there aren’t any further extensive goals to pursue. Therefore, debaters and judges in these paradigms do not need to play any fictitious roles but themselves.

This stance is appropriately criticized by Ulrich that to say debate judge is a debate judge is a senseless tautology (Ulrich, 1986). Even if debates are just games and role of judges is to follow the rules, the rules still need to be described and paradigms are to describe such. While some major rules can be cross-domain, rules in details are often domain specific and therefore only paradigms with analogies for specifying which domains and genres of communicative activity participants should expect can fill the blank.

Both types of the current debate competitions at least in Japan fall into the third category that is Future Seeking Debate. They don’t seek truth but better future and choose collective actions (= policy) for it. The paradigm still dominant for the Prepared Debate Contests is called “Policy Making Paradigm” and in terms of goal, there is no difference between Impromptu Debate Contests and Prepared Debate Contests. However, roles and perspectives of involved parties in debates of these two are slightly different. Here we name the paradigm of Impromptu Debate Contests “Parliamentary Paradigm”.

Policy Making Paradigm sees adjudicators more as ideally specialized practitioners of policy making such as bureaucrats with formal jurist training. Here the debates are judged by formal cost benefit analysis of the policy, modeling the expert decisions by idealized bureaucrats. Parliamentary Paradigm sees their adjudicators as ordinary citizens with voting rights at elections of proportional representation system. Voters rarely know the details of legal circumstances or exact volume of predicted cost-benefits and political parties facing an election of proportional representation system do not explain such either. They vote putting more priority on their moral value, principles and rough estimation of cost-benefits and so do the political parties.

There are more marginal differences appearing from the same root. For example, despite of some divergent views like Hollihan’s (Hollihan, 1983), conditional arguments/stances are tolerated by many adjudicators in Policy Making Paradigm until the last phase of debates but few accept them in Parliamentary Paradigm. It is common in Policy Making Paradigm to allow adjudicators to award tie and put the presumption on the Negative team in case of tie while Parliamentary Paradigm does not allow their judges to award tie in any circumstance.

This difference of perspective also influences the value of structure and entertaining delivery of arguments. While Policy Making Paradigm tries hard to focus on logos especially based on System Analysis (Boehm, 1976), Parliamentary Paradigm sees equivalent significance in pathos as well as logos (D’Cruz, 2003, Jones, 2005, Lam, 2004, Lee, 2003 & Salahuddin, 2003).

Comparing to the Policy Making Paradigm focusing on logical aspect of cost-benefit issues, evaluation by Parliamentary Paradigm is based on multiple aspects of argumentation and therefore more holistic and less systematic. In Policy Making Paradigm, rules for adjudicators’ decision making process are more formal, transparent and predictable.

Despite of the differences above, in broader sense, Policy Making Paradigm and Parliamentary Paradigm are seeking the same goal. The only difference lies in their approaches. Not few mistakenly prejudge that at tournaments with Parliamentary Paradigm they debate over value principles alone off specific policy choice but that is not the case. Fundamental goal of the debate in Parliamentary Paradigm is to choose a policy at the end and relevance of arguments with ethical principles cannot be separated from whether they justify or condemn the proposed policy.

3. Formal-Material Distinction

Paradigms for academic debates can be analyzed based on their formality as well. There are formal paradigms and material paradigms. This distinction follows the distinction of material rationality and formal rationality suggested by Max Weber’s sociology of law (Weber 1975, 395-397).

Material paradigms seeks debate adjudication to follow everyday substantial judging in some sense, for example, of judging done in court or in the field of science. Formal paradigms seek debate adjudication follow formal rules, giving priority to consistency of judging and due process. The criticism against the “debate judge as debate judge” paradigm can be interpreted as criticism for being extremely formal.

It is not the aim here to distinguish the debate paradigms as either material or formal paradigms, like being either black or white. The Stock Issue Paradigm is material in a sense that it models substantial court decisions, but formal in a sense that it cuts down the debate to certain number of stock issues. Any debate paradigms have both aspects; just some of them are blacker or whiter. Debate adjudication should necessarily seek the balance of the materialism and formality.

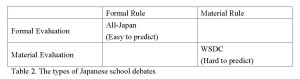

In this sense, we may say Prepared Debate Contests with Policy Making Paradigm slant toward the formal side and Impromptu Debate Contests with Parliamentary Paradigm slant more toward the material side. Formality, such as usage of citations as evidence, is more heavily weighed in Policy Making Paradigm. The case of “tie” awarded in Policy Making Paradigm happens if the adjudicator decides that both teams failed to provide the “formal requirements” of the arguments necessary for arguing the policy in the expert sense.

4. English Debate Education in Japan

Japanese history of debate education and debating competitions is long. However not like collegiate level but at school level, nation-wide institutionalization happened in only recent years. The biggest national tournament in Japanese language only started in 1996 but it is sill with longer history comparing to the one in English which was established in 2006. In terms of size, the English one is growing very fast.

In Japan, English is a Foreign Language and vast majority of students/pupils access English only during class time. But obvious trend of globalization incentivizes them to learn how to represent themselves in international settings.

By conducting a survey with 7000 business persons in Japan, Terauchi found that needs of further speaking competence in English is larger than those for other three skills (reading, listening and writing) as follows (Terauchi 2009, p.9).

(1) Learners with TOEIC score 900 or above can complete 90% of “easy” tasks of all 4 skills

(2) Even learners with TOEIC score 900 or above have difficulties in completing “complicated” tasks of speaking and writing. (50-90%)

(3) Learners with TOEIC score between 800 and 900 can deal with 70-90% of “easy” tasks of listening, reading and writing but 50-90% of them of speaking

(4) Only 30% of learners with TOEIC score between 800 and 850 can deal with “complicated” tasks of speaking and writing.

In the Terauchi’s survey, many subjects expressed necessity of introducing training for productive communication competence such as presentation, speech and debate to school education and job training at companies as follows (Terauchi 2009, p.9).

(1) As many Japanese are okay with conversations but presentations and speeches, we should introduce training for such. (Subject with TOEIC score above 900)

(2) Japanese are poor at debate and speech in Japanese or English. We need to improve programs for critical thinking skills and liberal arts. (Subject with TOEIC score above 600)

(3) Rather than teaching English from younger age, we should focus on logical structure of arguments and speech skills in order to improve our communication in English. (Subject with TOEIC score above 750)

(4) Communication is not about language per se but abilities for logical thinking and decision making. (Subject with TOEIC score above 800)

(5) We need training for logical speaking before learning English further. (Subject with TOEIC score above 800)

From Terauchi’s survey, we can presume that not only linguistic barrier but difference of structure, links and priorities in argumentation makes speech and presentation in English harder for them.

Considering the EFL circumstance above and the facts that most of the participants in the All Japan High School English Debate Tournament are with only one or two year experience in debating and the tournament is relatively young, adjudication there is expected to be transparent and predictable. All the rules and their application need to be understood by newcomers and adjudication has to be done as they understood. It was only natural that the adjudication style at the All Japan High School English Debate Tournament is that of Policy Making Paradigm. Not only that, the tournament required both adjudication and debates to follow very formalistic rules. For example, only two issues (Advantages / Disadvantages) can be presented each from both competing teams, and issues should be presented with proper evidence etc.: Judges are required to ignore the issues that violate the rules.

Having said that, the winner of the tournament is dispatched to the World Schools Debating Championships (WSDC) and adjudication there is in Parliamentary Paradigm. Depending on when the WSDC takes place in a year, the Japanese champion team has to shift themselves from Policy Making Paradigm to Parliamentary Paradigm in minimum five weeks.

5. Major Differences

In minimum five weeks, the Team Japan is required to adjust their speeches so that they can put more emphasis on ethical principles rather than cost-benefits. That is one of the most apparent targets. Even if slavery was beneficial in any way, in every day life, it may be treated to be unethical even to bring up the issue because slavery is wrong. Similarly, obliging every public building to meet standards to accommodate physically challenged citizens can be a significant cost but gain support because it is right thing to do. On what principle we think the proposal is right or wrong, why the particular principle is true and important, why the principle is the most relevant in the specific debate etc. The team needs to learn how to argue these out apart from the system analysis to prove if the proposal is beneficial or not.

Another target we set is to learn sensitivity in diversity. While participants of national tournaments are with relatively similar backgrounds, participants of the WSDC are diverse. They need to learn how to make their speeches sensitive enough to avoid hurting feelings of other participants from diverse background. Especially sensitivity towards socially weak and minority groups is essential. This is important as the team earnestly wishes to enjoy positive exchanges with delegates from other countries. But at the same time, Style (= pathos) is a valid factor of evaluation by the adjudicators at the WSDC. Adjudicators may deduct speaker score based on the politically incorrect expressions and that is an extra incentive for the team to stay politically correct. This also requires vocabulary building in English. At national tournaments audience do not demand word choice beyond comprehensible one. But at international tournaments, they have to compete in careful word choice to make their speech sound sensible and persuasive with English as the Native Language speakers.

The team spend substantial portion of their limited training time before the WSDC in order to adjust their speeches to the Parliamentary Paradigm focusing on the two major differences above.

Adjudication in Parliamentary Paradigm, at first, seems to the students too ambiguous, less predictable and frustrating as it is less formal both in terms of rules and evaluation as shown in Table 2. Not like cost-benefit comparison based on the system analysis with relatively set requirements and procedures, comparison of values and ethical principles can sound either relevant or irrelevant depending on adjudicator. Similarly, in which field the adjudicator is most sensitive is highly due to the personal background and which wording sounds offensive to them is less predictable. It was a surprise that the students did not show the rejection for long. In most cases, they showed their discomfort on this only for two weeks.

6. Changes

Understanding the paradigm and adjusting their speeches according to the paradigm are different tasks. Minimum for the five weeks, the Team Japan members received feedback intensively on these two points i.e. issue selection putting priority on ethical principle and significance of sensitive wording. The major shift was observed in their cultural awareness and sensitivity rather than in the issue selections. At the national tournaments, there were a number of potentially offensive statements made by the speakers. Followings are examples.

(1) On lowering the age of adulthood to eighteen

NEG “Under the status quo, you need parent’s approval to marry until twenty and boys don’t have to marry in case of unexpected pregnancy of their partners. But after the plan is taken, the girls will be able to pressure them to marry and life of boys with bright future will be ruined.”

(2) On banning dispatched working, v. NEG “dispatched working is the only option for women and elders”

AFF “Women and elders make a very little proportion of dispatched workers and so very little impact.”

At the national tournament, adjudicators are not allowed to dismiss the arguments based on their moral values. They have to quietly wait for the response from the opposition team and in case there is no rebuttal, they basically have to evaluate as it was presented. Maximum intervention permitted is, perhaps, to deal with it as lower priority comparing to the other issues presented in case the significance of the issue was not well explained or there is no explicit comparison given by speakers. In this circumstance, there is weak incentive for debaters under pressure of competition to avoid such statements.

As mentioned above however, at the WSDC, pathos is a valid factor to decide who wins the debate. And therefore extra effort in choice of issues and expressions is made by the competitors. After five weeks preparation, the Team Japan members learned how to avoid stereotypical prejudice. They avoided specifying gender of victims/offenders when they debated over marital abuse. Similarly they avoided specifying regions that current holders concentrate in a debate over cultural treasures to be returned to the areas of origin. But further on, the following remarks made after participating in the WSDC illuminate their change.

(1) A topic for a domestic tournament for school students was chosen as relaxing Japanese immigration policy. The following is what an ex-member of the Team Japan said.

“It is a great topic with a concern. If debaters talk as if foreigners were criminals or source of social disharmony, it would be very unpleasant but is a real risk with that topic.”

(2) In a debate if we should set a quota for female in board members in business, the Negative team (EFL) misunderstood that the proposed quota limits the maximum number of women in business not the minimum. The following is what the Team Japan member said.

“It is hard to detect which of the plural meaning on the dictionary fits in the context especially without daily media in the target language

From above two examples, we see the students after the training and experience of international exchange now take careful thought on perspectives of others from different background, especially weak ones in the community.

7. Conclusions

This study analyzed the two different debate adjudication paradigms dominant at contemporary debate competitions. Both are to choose a policy and therefore in the same category in a broad sense. The difference only lies in perspectives and formality. Each has merits and demerits as follows.

(1)With Policy Making Paradigm, debaters can test maximum range of value without bounded by social dogma. But it may end up with somewhat “unethical” arguments hardly accepted by the society outside of debate competitions.

(2)With Parliamentary Paradigm, how and how much an adjudicator finds an expression offensive depends on his/her background and is not very transparent. But it might provide learning opportunity about cultural/social sensitivity for students.

As mentioned in the fifth section on changes, there were changes observed before and after the training for shifting from a paradigm to another. Whether this attitude change is due to the adjudication paradigm is not well examined yet but the further possibility and effects of training for the critical cultural awareness should be more explored.

It may be appreciated that students can have the chance to learn both. But it needs further study on the balance between the formal and material paradigms. Questions should be raised considering the sequence (should formality be taught first or vice versa) and the emphasis (should we put more weight on the pathos etc.).

NOTE

[i] This research was supported by the Keio Research Center for Foreign Language Education’s Action Oriented Plurilingual Language Learning (AOP) Project, funded by the “Academic Frontier” Project for Private Universities which matched a fund subsidy from Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) of Japan, 2006.

REFERENCES

Boehm, G. A.W. (1976). Shaping decisions with systems analysis. Harvard Business Review, 54(September), 91-99.

D’Cruz, R. (2003). Australia-Asia Debating Guide (2nd ed.). Melbourne: Australia Debating Federation.

Hollihan, T. A. (1983). Conditional arguments and the hypothesis testing paradigm: A negative view. Journal of the American Forensic Association, 19(Winter), 171-178.

Izuta, T., Kaniike, Y., Kitano, H., & Namiki, S. (1985). Gendai Debate Tsuron [Introduction to Contemporary Debate]. Tokyo: Debate Forum Press.

Jones, A. (2005). Sound and fury? Towards a more objective standard for manner. Monash Debating Review, 4, 47-49.

Lam, A. (2004). A primer to adjudication. Monash Debating Review, 3, 78-83.

Lee, D. (2003). A plea for reason-based adjudication. Monash Debating Review, 2, 46-56.

Rowland, R. C. (1984). The debate judge as debate judge: A functional paradigm for evaluating debates. Journal of the American Forensic Association, 20(Spring), 183-193.

Salahuddin, O. (2003). What’s the matter with manner? Monash Debating Review, 2, 57-64.

Snider, A. C. (1984). Games Without Frontiers: A Design for Communication Scholars and Forensic Educators. Journal of the American Forensic Association, 20(Winter), 162-170.

Terauchi, H. (2009). Businessman 7000 nin Ankeito no Hokoku [Report on Survey with 7000 Businessmen]. Keio University Research Center for Foreign Language Education Symposium, 8, 6-15.

Ulrich, W. (1986). Judging Academic Debate. Chicago: National Textbook Company.

Zarefsky, D. (1982). The perils of assessing paradigms. Journal of the American Forensic Association, 18(Winter), 141-144.

Weber, M. (1976). Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft (5. revidierte Auflage. Johannes Winckelmann (Ed.).). Tübingen: J. C. B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck).