ISSA Proceedings 2010 – Argumentation In The Context Of Mediation Activity

This paper examines interaction in the course of dispute mediation to explore argumentation in the context of mediation activity. The mediation sessions involve divorced or divorcing couples attempting to create or repair a plan for child custody arrangements. A practical problem participants face when attempting to deliberate is that out of all the possible ways the interaction could go they must create this activity out of their conflicted circumstances. The empirical aspect of this project provides material for reflecting on mediation activity and understanding argumentation.

This paper examines interaction in the course of dispute mediation to explore argumentation in the context of mediation activity. The mediation sessions involve divorced or divorcing couples attempting to create or repair a plan for child custody arrangements. A practical problem participants face when attempting to deliberate is that out of all the possible ways the interaction could go they must create this activity out of their conflicted circumstances. The empirical aspect of this project provides material for reflecting on mediation activity and understanding argumentation.

An existing collection of transcripts from audio recordings of mediation sessions at a mediation center in the western United States serves as a source of interactional data. The transcripts are from sessions held in a public divorce mediation program connected with a court where the judge approves the decision (Donohue 1991). The participants in the mediation sessions are couples going through a divorce or divorced couples (re)negotiating their divorce decrees. The sessions involve one mediator. The mediation sessions are mandatory for participants. If they cannot reach a settlement they can opt to go to court to resolve their dispute. The participants can also choose to have more than one session. The mediation sessions under study took place 2 hours prior to the court hearings. The length of sessions varied but in the majority of cases it was about 2 hours.

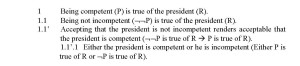

Argumentation scholars sometimes equate mediation with a certain type of argumentative activity (Eemeren & Houtlosser 2005) or a kind of dialogue type (Walton 1998). Walton (1998), for example, considers mediation to be an example of negotiation type of dialogue that presupposes conflict of interests. The aim of this type of dialogue is personal gain. It has its specific features such as the commitments of participants towards some course of action, the structure similar to the critical discussion, and moves that fit its structure and goal (e.g., threats).

Eemeren and Houtlosser (2005), in their turn, distinguish mediation as a conventionalized type of argumentative activity that is distinct from negotiation and adjudication. They argue that mediation involves a difference of opinion rather than conflict of interests. Like critical discussion, it develops through four stages of argumentation.

Dispute mediation, however, is a more complex activity than pictured in either of these two approaches. Clark (1996) points out that one “activity can be embedded within another” (p. 32). Examining mediation activity as it occurs naturally shows that this process is multidimensional as it is accomplished through various dialogue activities. It involves negotiation, information exchange, recommendation giving, and clarification among other dialogue activities. The point of models such as Walton’s or van Eemeren’s is to simplify the complexity of an activity in relevant and meaningful ways. In some sense, different stages of an argumentative activity imply that other kinds of activity are necessary for this activity to develop. However, all these stages are argument oriented. The problem is that both models take an argument to be a primary activity as opposed to Jacobs and Jackson’s (2006) idea of argument being subordinate to some other kind of activity. In dispute mediation, not all dialogue activities involve argument. When it arises, it serves as a repair mechanism for the mediation activity.

Another problem with these approaches is that they are normative and consider mediation in terms of some ideal type of interaction, whether an argumentative activity type or dialogue type. However, activity types are never given, they are produced. This production is a joint achievement of all the participants. Speaking about joint activities, Clark (1996) states, “One reason joint activities are complicated is two or more people must come mutually to believe that they are participating in the same joint activity” (p. 36). The development of the activity involves constant negotiation of the interactants of what they are doing in a given moment and of what they are trying to accomplish. The participants of the activity have different sets of responsibilities (Clark 1996). These responsibilities and the actions participants perform “depend on the role they inherited from the activity they are engaged in” (Clark 1996, p. 34). In the course of the mediation session, the mediator has a leading role and tries to design talk in a certain way, to institutionalize it in the sense that mediators are disciplining the performance through language use. The institutional goal of the mediation session puts constraints on what can be done in this interaction and how the disputants can manage their disagreement. The mediator makes moves to institutionalize the talk in the moment of the session by advancing certain dialogue activities and preventing others. However, all the participants contribute to constructing the way the interaction unfolds.

Walton and van Eemeren and his colleagues emphasize the use of discourse as a basis for realizing what the arguments are in a dialogue, that in turn is a way of doing informal logic analysis of argument quality. The focus of the current study is on argumentative conduct and the qualities of reasoning realized in the joint performance of activity. This draws a different kind of attention to understanding and evaluating argument, that is, evaluating argumentation and the actions performed to construct a dialogue quality.

Another feature of joint activities is multiple goals. While one goal can be dominating (e.g., for the mediation activity it is an institutional goal of making arrangements for the children), participants can also pursue procedural and interpersonal goals and have private agendas. Thus, disputants can have agendas of their own and engage in shaping an interactivity that is different from what the mediator is designing. This can lead to interactional tensions.

In this respect, what is of interest here is how disagreement is managed and how the mediator’s contributions construct a preferred form of interactivity. This paper will address this issue at the level of dialogue activities participants initiate with the special focus on the dialogue activity of having-an-argument.

O’Keefe (1977) makes a distinction between making-an-argument and having-an-argument. In the first case, an argument is a speech act “which directly or indirectly support or undermine some other act by expansion along … a set of logically related propositions known as felicity conditions” (Jacobs & Jackson 1981, p. 126). In the second case, an argument is an activity that presupposes “some exchange of disagreement that extends an initial open clash” and does not necessarily involve reason-giving (Jacobs & Jackson 1981, p. 127). Having-an-argument is institutionally dispreferred as it does not contribute to resolving a dispute and creating arrangements and is likely to lead to escalating the conflict. The content of having-an-argument would revolve around the issues of negative features of one’s personality and actions. Although the topic is a common characteristic for these dialogue activities, what distinguishes this dialogue activity is mutual performance of the participants, the stance they take towards each other through the use of language and different moves they make. When the disputants engage in having-an-argument, they would take on the roles of people in conflict and become oppositional. In the prototypical case of having-an-argument the disputants would hit each other verbally[i] and focus primarily on the character of the other party. They would use offensive language, make insults, accusations, challenges, threats, and the like. There will be exchanges of disagreement but the following moves would not provide support for the claims and would not be necessarily connected to the preceding moves in any rational way. The moves can be also recycled in an aggravated form. This type of performance is off-task as name-calling affects the quality of interaction. The way the interaction unfolds does not allow the participants to share opinions. These moves also present a threat for the image of the disputants. Thus, the disputants focus on the restoring their image rather than working out an arrangement.

In more subtle cases, the opposition described above would not be so obvious. The disputants would try to prove who is right or wrong by bringing evidence that depicts the other party unfavorably. It is not a pure case of having an argument without making an argument. Instead, the making of arguments is done in such a way that undermines the image of the opponent (i.e., it carries what Aakhus (2003) calls negative collateral implications) and treats the mediator as a judge. The disputants would make assertions, often addressed to the mediator, about the other disputant’s character or actions. The disagreement would develop over the sequence of moves as the participants would provide support for their claim, objected to or countered by another participant. These subtle cases are problematic for interaction as well, as the disputants use the mediator to attack the other disputant and prove that they are bad, which is likely to develop into a primitive argument.

Example 1 and 2 illustrate how this dialogue activity unfolds. Prior to the episode in example 1, the disputants were having a quarrel about custody issues. The (ex)-wife was accusing her (ex)-husband of his intentions to take the child away from her and expressing her determination not to let that happen. In the episode below, it is the (ex)-husband who takes an accusatory position. He claims that his (ex)-wife is not acting as a good mother as she does not take care of their child all the time, which the (ex)-wife denies. The mediator makes moves to terminate the development of the dialogue activity.

1.

130M: OK now the other thing is

131H: If she’s [uh you know not] a fit mother or something=

132M: [a temporary order]

133H: = y[ou know] if she’s not in some way=

134W: [I’m not ]

135H: = [capable of ]

136M: = [Is she un- is she un] fit?

137H: = coming home,

138M: Is she u[nfit?

139H: [No she’s a fit mother when she is at home

140W: Oh my [God

141H: [But you know I don’t know my my [uh in laws take] care of =

142M: [Okay there’s ]

143H: = [him] all the time now=

144M: [OK]

145W: = [No they do not ]=

146H: = [from what I understand]=

147M: = [OK let’s ]=

148H: = [She doesn’t come home at night]=

149M: = We’re not this is not a, [trial]

150W: [I have] been ho[me every ]=

151M: [Kathryn ]=

152W: = [single=

153M: = [Kathryn

154W: = night [Michael

155H: You would be investigated.

156M: Hey Kathryn excuse me, [we’re not, ] this is not a trial

157H: [What do you want]

158W: You disgust me=

159M: = Okay

160W: You are a disgusting person Michael

161M: [Kathryn ]

162W: [You will] lie ah ((WHISPERED)) God=

[You’re gonna get yours in the end ( ) you watch] it.

163M: [Excuse me, Kathryn excuse me please. ] Okay w- we’re not

trying the case, I don’t wanna hear any more arguments. All I wanna do now is see if there’s any way you two can agree to some sort of temporary plan because if you don’t, then the court can help you with that.

In turns 130 and 132, the mediator (M) makes moves to refocus the interaction on the task at hand by providing a minimal response to the preceding move and introducing a new topic, which is a temporary order. However, the (ex)-husband (H) interrupts and makes a claim that his (ex)-wife (W) is not capable of taking care of their son. In turns 131, 133, 135, and 137, he makes an attempt to justify his intentions to have the child with him by depicting Was not being a fit mother all the time, which is opposed by W in turn 134. Instead of pursuing the shift initiated in turns 130 and 132, M gets engaged in the current dialogue activity. While H shapes his accusation of W’s behavior in a mitigated manner by using the conditional mood, M asks H directly if he considers W to be an unfit mother in general (turns 136 and 138). M’s move opens a possibility for the current activity to continue. H makes a statement that W is fit when she is at home (turn 139). Further on, he makes a point that his in-laws take care of the child all the time (turns 141 and 143) and W is not at home at night (turn 148). He warns W that she will be investigated (turn 155). Thus, H does not call his W unfit directly but references he makes and facts he brings into the interaction depict her in a negative way. W expresses her disagreement in turns 140, 145, 150, 152, and 154. H asks W what she wants (turn 157). W attacks H’s personality by using offensive language such as “a disgusting person” (turns 158 and 160) and by depicting him as a liar (turn 162). M makes a number of moves to stop the development of the dialogue activity and to make a shift in the discussion. M uses the marker “Okay” (turns 142, 144, 147, and 159) to indicate the termination of the dialogue activity and/or topic, addresses W by name (turns 151, 153, 156, and 161) to get her attention, and directly points out that H and W engage in an inappropriate activity (turns 149, 156, and 163). However, this dialogue activity continues, and M finishes the session.

In this episode, there is a clash of pursuing projects that are going on, the one that M is trying to enforce, and the one that H is initiating. H essentially makes a case that W is an unfit mother. W resists this. M gets involved in this dialogue activity, and his/ her move in turn 136 puts the disputants into antagonistic talk with each other. As the dialogue activity of proving who is right or wrong continues, H and W exchange accusations of each other. M intervenes as this dialogue activity is likely to escalate the conflict, which indeed happens later in this episode (turns 155-162). H is making a claim, W denies. Though it can be proven, M does not tolerate this exploration. According to M, the parties’ moves construct a dialogue activity that is more appropriate for the trial (e. g., “this is not a trial” (turns 149 and 156), “we’re not trying the case” (turn 163)). Attacking each other and defending themselves are the moves that the participants make in the court. In order to convince the judge and win the case, they have to present themselves in a positive way and discredit the opponent by different means. However, undermining the image of the opponent is improper for the mediation session (which is evident, for example, in the mediator’s statement “I don’t wanna hear any more arguments” in turn 163). The mediator does not make any decisions so there is no point in convincing the mediator in their rightness. What we have here is two different designs for talk that reveal differing kinds of rationality. A classic feature of mediation sessions is focus on future. A trial, on the contrary, is about adjudicating about the past, getting the truth, distributing the blame, and assigning punishment. At the beginning of the episode, H was giving facts about the situation. However, in the progression, the talk is becoming about a character. It is not a simplistic argument the disputants engage in. In this episode, it is having an argument in the process of making an argument. As the interaction progresses, however, this dialogue activity develops into primitive argument and quarrelling. The disputants are not making arguments any more but are merely exchanging disagreements. While earlier in the episode the focus was on W’s character, here, W makes moves to hit H verbally and depict him unfavorably. The conflict escalates through a challenge (e.g., in turn 157, H challenges W with his question), through insults and recycling prior moves in aggravated form (e.g., a generalized assessment of H’s personality “You are a disgusting person Michael” in turn 160 is stronger than a specific one “You disgust me” in turn 160), and through an accusation (“You will lie” in turn 162) and a threat (“You’re gonna get yours in the end ( ) you watch it” in turn 162).

M intervenes directly to reframe the talk. M reminds the parties what they are supposed to do during the session, namely, they have to work out a temporary plan together (e.g, “All I wanna do now is see if there’s anyway you two can agree to some sort of temporary plan” (turn 163)). The words M uses create a contrast between what H and W were doing (i.e., having a quarrel, which implies disagreement and separation) and what they should do (i.e., they have to agree to a plan, which implies some kind of union). In this way, M once again emphasizes the necessity of collaboration between H and W.

This episode is an example of two lines of dialogue activities that are in clash. The disputants engage in having an argument and orient toward proving their own position. The activity of defining who is right or wrong is not appropriate, as this cannot be established. The mediator treats this as not possible and not part of mediation. Instead, making arguments must be geared toward advancing a plan for managing the children. The mediator’s moves are geared to shift this dialogue activity to the planning discussion and put the disputants into different social relations. Jacobs and Aakhus (2002a) point out that mediators often show no interest in resolving the points of clash and discourage the elaboration of the disputants’ positions through making arguments. Mediators do not cut off all the arguments, however. In planning or negotiating, the disputants can still make arguments but on a different issue, that is, they can make arguments that have to do with the future focus, not the past.

In the previous example the mediator was the one who indicated having-an-argument as an inappropriate activity. The disputants themselves can recognize that they are off-task. For example, in example 2 it is one of the parties, namely the (ex)-wife, who refers to the dialogue activity of having-an-argument and points out that she would not like to engage in this dialogue activity. The disputants exchange a number of accusations. The (ex)-wife raises doubts about her (ex)-husband’s good intentions to have their daughter Alison to live with him and not giving a Christmas gift to Alison. In his turn, the (ex)-husband accuses his (ex)-wife of neglecting their child and being a cause of relationship issues between her and Alison.

Finally, the (ex)-wife makes a move to stop the current dialogue activity.

2.

184W : Is that the only reason why you want her? I mean come on now or is it because you don’t want to pay child support?

185H : I know this erroneous statement was going to come up let me point thus out to ya. When Alison did come over to me and signed all the papers over to me now

I have of choice of whether I want to pay child support. This is a great thing about history you can’t change what’s happened in the past. When Alison come and live with me I didn’t stop her allowance. I could have I give half of it to her for weekly allowance I put the other half in the bank for her future education or whatever she wanted to use it for when she got older. Her mother never comes

and visited her one time in the year and a half

186W: Wait

187H : No somebody tell me I don’t want to pay child support I did it of my own vol[ition nobody forced me to]

188W : [I didn’t wait wait wait. I ] didn’t come and visit Alison in the year and a half?

189H : That’s right

190W : Wait just a minute okay? How many times did I go over to the house and take Alison to the ( )? Did I or did I not go to your house and send Alison a birthday present you didn’t give her nothing for Christmas this year.=

191H : After the suicide attempt you’re referring to?

192W : Yes=

193H : No I’m speaking up to the point of the suicide attempt=

194W : She wasn’t speaking to me

195H : Oh

196W : I made the first attempt to go over there

197H : Why wasn’t she speaking to you?

198W : Because we got into an argument in the front yard she called me a bitch

199H : Holds a grudge a long time doesn’t she a year and a half?

200W : Me hold a grudge?

201H : No Alison

202W : Not me

203H : If that’s the problem how come she held a grudge for a year and a half?

204W : Why isn’t Kelly speaking to me now did I ever do anything to hurt her?

205H : Because she sees what’s happening

206W : The only thing I want to say I don’t want to argue with you okay? Whatever’s best for Alison

207H : My oldest daughter’s first words were

((15 turns omitted as these continue the exchange in the manner of the preceding turns))

223M : [[Loretta you’re saying that uh what is in the best interest of Alison?

In this excerpt, W makes a supposition that H wants their daughter Alison to live with him because he is not willing to pay child support (turn 184). H denies this accusation and brings in the facts that can be evidence that W is wrong. In his turn, he accuses W of not visiting Alison once while she was living with him (turn 185). W challenges H’s accusation (turn 188 and 190) and accuses H of not giving any Christmas gift to Alison (turn 190). In turns 191-193, H and W clarify to what time period each of them is referring. In turns 194-203, the focus of the interaction is on why Alison was not speaking to W. In turn 204, W questions H why their elder daughter Kelly is not speaking to her. H’s point is this happens because Kelly sees what is going on between the mother and Alison (turn 205). In turn 206, W backs off saying that she does not want to argue with H and is willing to do anything that is best for Alison. Thus, she points out what activity they have engaged in, that is, having-an-argument, and makes an attempt to stop it. As the dialogue activity continues, M intervenes (turn 223).

Similar to example 1, in the excerpt above, H and W make a number of moves that aim at proving who is right and who is wrong but at the same time depict each other in an unfavorable light. W’s supposition that H tries to avoid paying child support (turn 184) and her accusation that he did not give any gift to Alison threaten H’s face as these moves portray H as a bad father. In his turn, H creates an image of W as an unfit mother. First, he accused W of neglecting her duties as a mother (e.g., “Her mother never comes and visited her one time in the year and a half” (turn 185). Next, he did not accept W’s explanation why Alison and she had had communication problems (e.g., “Holds a grudge a long time doesn’t she a year and a half?” (turn 199) and “If that’s the problem how come she held a grudge for a year and a half?” (turn 203)). By expressing his lack of understanding of how one quarrel could result in a year and half of not speaking to each other and repeating the same question twice, H makes it clear that there should be a more serious reason for a relationship problem between W and Alison, and W is likely to be responsible for this. Speaking about the lack of communication between W and their other daughter, he alluded again that it might be W’s fault that they have a problem (“Because she sees what’s happening” (turn 205)). Kelly did not stop talking to H, so W must have been doing something wrong if she refused to speak with her. The moves that H and W make are typical for the dialogue activity of having-an-argument. W makes an attempt to terminate this unproductive dialogue activity by making a statement that she does not want to participate in it and by shifting the focus of the interaction from relationship problems back to the interests of the daughter. Her move, however, did not result in bringing the end to having-an-argument, and later on M had to intervene to stop it. Thus, participants themselves signal recognition of the inappropriateness of the dialogue activity and initiate its termination even though their attempt may fail as they do not have authority to do that. In contrast to example 1, where M was trying to terminate a dialogue activity at the early stage of its development, in the episode above M does not mind the disputants building their argument as the having-an-argument features are not so pronounced as in the previous example and the facts they bring might be helpful for future plans. This example illustrates that forms of dialogue activity are emergent and what is going on is not always obvious. Indeed, it may have gone in a different direction but it turned into having-an-argument. As this dialogue activity progresses, M intervenes to make shift by referring to what was mentioned earlier in the interaction (i.e., W’s mentioning of acting in the interest of the child). At the same time, it is not simply the primitive argument that is problematic here but the fact that the disputants are treating their turns as though they are cross-examining a case in front of a judge. The disputants interchangeably assume the role of an interrogator and question each other about the past events in the way that depict the other party unfavorably while showing themselves in a positive light. Their moves do not treat the mediator as a mediator. Their contributions construct the debate and treat the mediator as the judge. The mediator cuts this dialogue activity off to initiate a different kind of dialogue activity.

In line with work done by Jacobs and Jackson (Jackson, 1992; Jackson & Jacobs, 1980, 1981; Jacobs & Jackson, 1989, 1992) and Jacobs and Aakhus (2002a, 2002b) the present study draws the attention to the process of how reasoning between the participants is embedded in the activity. The actions used to perform a certain type of activity are related to the epistemic quality of that activity. Mutual performance of actions takes a trajectory that may not be expected. Participants may be reasonable on separate moves, but when these moves are put together they do not necessarily have this quality. Moves and countermoves give a shape to disagreement space (Jackson 1992) that is always emergent. What is taken from this disagreement space to construct the next communicative move can be beyond what is expected by anyone in the interaction. Disputants may bring reasonable things to talk about (e.g., whether the other party can be trusted if he or she violated trust in the past) but sometimes this action takes into a different direction.

Mediation is an institutionalized type of discourse in the sense of disciplining the performance of participants. The argument plays a different role there than, for example, in the court, where the aim is to establish the truth and assign responsibilities. In court, the participants bring in facts about the past to make an argument to support their claim. In the course of the mediation session making an argument about the past is discouraged, which is related to the orientation of mediation sessions on the future. The disputants can make arguments but they should do this with the future focus for planning and negotiating the arrangements for their children. In this case the disputants are reasoning together to find a better solution for their problem. When the disputants engage in cross-examination similar to what happens in the court and a primitive argument, they are in a way reasoning against each other. What is reasonable for one type of activity (e.g., a court trial) is not acceptable in the other one (e.g., dispute mediation). Bringing in facts that depict the other party in a negative way, for example, is appropriate for trial but not for dispute mediation. Acting in adversarial roles is normal for the court, while the roles of collaborators are encouraged in dispute mediation.

Another point about an argument in the context of mediation is that although making-an-argument or having-an-argument in their prototypical form do occur, what commonly happens in dispute mediation is having an argument while making an argument. In some cases a having-an-argument part is more pronounced and easily recognized by the participants, and the mediator cuts this dialogue activity at the early stage. In other cases it is not that obvious and is terminated by the mediator when it starts aggravating.

The mediator’s focal point is to try to construct a mediation activity, which involves acting strategically. The study expands the idea of strategic maneuvering beyond two-party argumentative discussion. It shows how this concept is applied to those who are not principals of dispute but who take on a responsibility for the quality of interaction. In a two-party argumentative discussion, arguers engage in strategic maneuvering to balance the goal of the discussion and their own needs. In a mediation encounter, disputants, who are principal arguers, act strategically to balance the institutional goal of the meeting and their personal agenda. The mediator’s strategic maneuvering is different as it orients toward the institutional goal and the quality of interaction. They use routine institutional practices to keep the disputants on task to constrain what becomes arguable. The concept of strategic maneuvering is usually related to traditional argumentative moves. The work that the mediator performs goes beyond that. Mediators’ strategic maneuvering manifests itself not just at the levels of presentational device (e.g., references and interventions they make), topical potential (e.g., topics they initiate), or audience demand (e.g., taking into consideration face concerns in framing interventions). The dialogue activities themselves that the mediator initiate and encourage are strategic moves of a higher level. With help of all these resources, mediators are doing persuasion about the nature of the given activity. The work that the mediator performs is to structure dialogue in such a way that disputants would be able to make contributions to create the process of deliberation.

NOTES

[i] That is what Walton (1995) calls a quarrel, and Jacobs and Jackson (1981) describe as having an argument without making arguments.

REFERENCES

Aakhus, M. (2003). Neither naïve nor normative reconstruction: Dispute mediators, impasse, and the design of argumentation. Argumentation: An International Journal on Reasoning, 17, 265-290.

Clark, H. H. (1996). Joint activities. In Using language (pp. 29-58). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Donohue, W. (1991). Communication, marital dispute, and divorce mediation. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Eemeren, F. H. van, & Houtlosser, P. (2005). Theoretical construction and argumentation reality: An analytic model of critical discussion and conventionalized types of argumentation activity. In D. Hitchcock (Ed.). The uses of argument: Proceedings of a conference at McMaster University (pp. 75-84). Hamilton: McMaster University.

Jackson, S. (1992). “Virtual standpoints” and the pragmatics of conversational argument. In F. H. van Eemeren, R. Grootendorst, J. A. Blair, & C. Willard (Eds.), Argumentation illuminated (pp. 260 – 269). Amsterdam: SicSat.

Jackson, S., & Jacobs, S. (1980). Structure of conversational argument: Pragmatic bases for the enthymeme. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 66, 251-265.

Jackson, S., & Jacobs, S. (1981). The collaborative production of proposals in conversational argument and persuasion: A study of disagreement regulation. Journal of the American Forensic Association, 18, 77-90.

Jacobs, S., & Aakhus, M. (2002a). What mediators do with words: Implementing three models of rational discussion in dispute mediation. Conflict Resolution Quarterly, 20, 177-204.

Jacobs, S., & Aakhus, M. (2002b). How to resolve a conflict: Two models of dispute resolution. In F. H. van Eemeren (Ed.), Advances in pragma‐dialectics (pp. 121‐126). Newport News, VA: Vale Press.

Jacobs, S., & Jackson, S. (1981). Argument as a natural category: The routine grounds for arguing in conversation. The Western Journal of Speech Communication, 45, 118-132.

Jacobs, S., & Jackson, S. (1989). Building a model of conversational argument. In B. Dervin, L. Grossberg, B. J. O’Keefe, & E. Wartella (Eds.), Rethinking communication Vol 2: Paradigm exemplars (pp. 153 – 171). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Jacobs, S., & Jackson, S. (1992). Relevance and digression in argumentative discussion: A pragmatic approach. Argumentation, 6, 161-176.

Jacobs, S., & Jackson, S. (2006). Derailments of argumentation: It takes two to tango. In P. Houtlosser & A. van Rees (Eds.), Considering pragma-dialectics (pp. 121-133). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

O’Keefe, D. (1977). Two concepts of argument. Journal of the American Forensic Association, 13, 121-128.

Walton, D. (1995). A pragmatic theory of fallacy. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

Walton, D. (1998). The new dialectic: Conversational context of argument. Toronto : University of Toronto Press.