ISSA Proceedings 2010 – The Use And Misuse Of Topoi: Critical Discourse Analysis And Discourse-Historical Approach

1. Introduction

1. Introduction

The Discourse-Historical Approach (DHA), pioneered by Ruth Wodak (see Wodak, de Cillia, Reisigl & Liebhart 1999; Wodak & van Dijk 2000; Wodak & Chilton 2005; Wodak & Meyer 2006; Wodak 2009), is one of the major branches of critical discourse analysis (CDA). In its own (programmatic) view, it embraces at least three interconnected aspects (Wodak 2006, p. 65)[i]:

1.’Text or discourse immanent critique’ aims at discovering internal or discourse-internal structures

2. The ‘socio-diagnostic critique’ is concerned with the demystifying exposure of the possibly persuasive or ‘manipulative’ character of discursive practices.

3. Prognostic critique contributes to the transformation and improvement of communication.

CDA, in Wodak’s view (ibid.),

is not concerned with evaluating what is ‘right’ or ‘wrong’. CDA … should try to make choices at each point in the research itself, and should make these choices transparent[ii]. It should also justify theoretically why certain interpretations of discursive events seem more valid than others.

One of the methodical ways for critical discourse analysts to minimize the risk of being biased is to follow the principle of triangulation. Thus one of the most salient distinguishing features of the DHA is its endeavour to work with different approaches, multimethodically and on the basis of a variety of empirical data as well as background information.

One of the approaches DHA is using in its principle of triangulation is argumentation theory, more specifically the theory of topoi. In this article, I will be concerned with the following questions: how and in what way are topoi and, consequentially, argumentation theory, used in DHA as one of the most influential schools of CDA? Other approaches (e.g. Fairclough (1995, 2000, 2003) or van Leeuwen (2004, 2008), van Leeuwen & Kress (2006)) do not use topoi at all. Does such a use actually minimize the risk of being biased, and, consequentially, does such a use of topoi in fact implement the principle of triangulation?

2. Argumentation and CDA

Within argumentation theory, Wodak continues (2006, p. 74),

‘topoi’ or ‘loci‘ can be described as parts of argumentation which

belong to the obligatory, either explicit or inferable premises. They are the content-related warrants or ‘conclusion rules’, which connect the argument or arguments with the conclusion, the claim. As such, they justify the transition from the argument or arguments to the conclusion (Kienpointner, 1992: 194).

We can find the very same definition[iii] in The Discursive Construction of National Identity (Wodak, de Cillia, Reisigl & Liebhart 1999, p. 34), in Discourse and Discrimination (Reisigl & Wodak 2001, p. 75), in The Discourse of Politics in Action (Wodak 2009, p. 42), in Michal Krzyzanowski’s chapter “On the ‘Europeanisation’ of Identity Constructions in Polish Political Discourse after 1989”, published in Discourse and Transformation in Central and Eastern Europe (Galasinska and Krzyzanowski 2009, p. 102), and in John E. Richardson’s paper (co-authored with R.Wodak) “The Impact of Visual Racism: Visual arguments in political leaflets of Austrian and British far-right parties” (manuscript, p. 3), presented at the 2008 Venice Argumentation Conference[iv]. In addition to the above definition, Richardson (2004, p. 230) talks of topoi “as reservoirs of generalised key ideas, from which specific statements or arguments can be generated”.

One could wonder about the purpose and the (ontological) status of the two definitions: are topoi “content-related warrants” or are they “generalised key ideas“? Because warrants are much more than just ideas; they demand much more to be able to secure the transition from an argument to a conclusion than just being “generalised ideas”, namely, a certain structure, or mechanism, in the form of an instruction or a rule. While ideas, or generalised ideas, lack at least a kind of mechanism the warrants seem to possess in order to be able to connect the argument to the conclusion. Let us proceed step by step.

3. How topoi are found…

In the above-mentioned publications, we get to see the lists of the(se) topoi. In the chapter “The Discourse-Historical Approach” (Wodak 2006, p. 74), we read that “the analyses of typical content-related argument schemes can be carried out against the background of the list of topoi though incomplete and not always disjunctive”, as given in the following table:

1. Usefulness, advantage

2. Uselessness, disadvantage

3. Definition, name-interpretation

4. Danger and threat

5. Humanitarianism

6. Justice

7. Responsibility

8. Burdening, weighting

9. Finances

10. Reality

11. Numbers

12. Law and right

13. History

14. Culture

15. Abuse.

In Richardson (2008, p. 4), we have exactly the same list of topoi, but this time they are characterised as “the most common topoi which are used when writing or talking about ‘others’“, specifically about migrants.

In The Discourse of Politics in Action (Wodak 2009, p. 44), we get the following list of “the most common topoi, which are used when negotiating specific agenda in meetings, or trying to convince an audience of one’s interests, visions or positions“. They include:

1. Topos of Burdening

2. Topos of Reality

3. Topos of Numbers

4. Topos of History

5. Topos of Authority

6. Topos of Threat

7. Topos of Definition

8. Topos of Justice

9. Topos of Urgency

In The Discourse of Politics in Action, we can also find topos of challenge, topos of the actual costs of enlargement of the EU, topos of belonging, and topos of ‘constructing a hero’. Here the analyses of typical content-related argument schemes as found in discourse are not just carried out “against the background of the list of topoi”, but some parts of discourse “gain the status of topoi” (topos of the actual costs…). Thus, as far as the status of topoi is concerned, we seem to have got a bit further: there is not just a list of topoi that can serve as the background for the analysis; more topoi can be added to the list. And, presumably, if topoi can be added to the list, they can probably also be deleted from the list. Unfortunately, in the publications I have listed, we get no epistemological or methodological criteria as to how this is done, i.e. why, when, and how certain topoi can be added to the list, or why, when, and how they can be taken off the list[v].

The most puzzling list of topoi can be found in Krzyzanowski (2009, p. 103). In this article we get the “list of the topoi identified in the respective corpora” (the national and the European ones – IŽŽ). They are[vi]:

Topoi in the national corpus

1. Topos of national uniqueness

2. Topos of definition of the national role

3. Topos of national history

4. Topos of East and West

5. Topos of past and future

6. Modernisation topos

7. Topos of the EU as a national necessity

8. Topos of the EU as a national test

9. Topos of the organic work

10. Topos of Polish pragmatism and Euro-realism.

Topoi in the European corpus

Topos of diversity in Europe

Topos of European history and heritage

Topos of European values

Topos of European unity

Topos of Europe of various speeds

Topos of core and periphery

Topos of European and national identity

Topos of Europe as a Future Orientation

Modernisation topos

Topos of the Polish national mission in the European Union

Topos of joining the EU at any cost

Topos of preferential treatment.

How these topoi were “identified”, and what makes them “the topoi” – and not just simply “topoi” –, we do not get to know; Krzyzanowski just lists them as such. Is there another list that helped them to be identified? If so, it must be very different from the lists we have just mentioned. Maybe there are several different lists? If so, who constructs them? When, where, and, especially, for what purpose and how? Is there a kind of grid, conceptual or in some other way epistemological and/or methodological that helps us/them to do that? If so, where can we find this grid? And how was it conceptually constructed? And if there is no such grid, how do we get all these different lists of topoi? By casuistry, intuition, rule of thumb? Are they universal, just general, or maybe only contingent? Judging from the lists we have just seen, there are no rules or criteria; the only methodological precept seems to be: “anything goes”[vii]! If so, why do we need triangulation? And what happened to the principle stipulating that CDA “should try to make choices at each point in the research itself, and should make these choices transparent?”

All this leads us to a key question: can anything be or become a topos? And, consequentially, what actually (i.e. historically) is a topos? Before we try to answer these questions, let us have a look at how the above-mentioned topoi are used in the respective works.

4. … and how topoi are used

In Discourse and Discrimination (Reisigl & Wodak 2001, p. 75), as well as in “The Discourse-Historical Approach” (Wodak 2006, p. 74), we can find, among others, the following identical definition of the topos of advantage:

The topos of advantage or usefulness can be paraphrased by means of the following conditional: if an action under a specific relevant point of view will be useful, then one should perform it (…) To this topos belong different subtypes, for example the topos of ‘pro bono publico’ (‘to the advantage of all’), the topos of ‘pro bono nobis’ (to the advantage of us’), and the topos of ‘pro bono eorum’ (‘to the advantage of them’).

And then the definition is illustrated by the following example:

In a decision of the Viennese municipal authorities (…), the refusal of a residence permit is set out as follows:

Because of the private and family situation of the claimant, the refusal of the application at issue represents quite an intrusion into her private and family life. The public interest, which is against the residence permit, is to be valued more strongly than the contrasting private and family interests of the claimant. Thus, it had to be decided according to the judgement.

If a topos were supposed to connect an argument with a conclusion, one would expect that at least a minimal reconstruction would follow, namely, what is the argument in the quoted fragment? What is the conclusion in the quoted fragment? How is the above-mentioned topos connecting the two, and what is the argumentative analysis of the quoted fragment? Unfortunately, all these elements are missing; the definition and the quoted fragment are all that there is.

And this is the basic pattern of functioning for most of these works. At the beginning, there would be a list of topoi and a short description for each of them (some of the quoted works would avoid even this step): first, a conditional paraphrase of a particular topos would be given, followed by a short discourse fragment (usually from the media) illustrating this conditional paraphrase (in Discourse and Discrimination, pp. 75-80), but without any explicit reconstruction of possible arguments, conclusions, or topoi connecting the two in the chosen fragment. After this short theoretical introduction, different topoi would just be referred to by names throughout the book, as if everything has already been explained in these few introductory pages.

It is interesting to observe how the functioning of these topoi is described (especially in Discourse & Discrimination, which is the most thorough in this respect): topoi are mostly »employed« (p. 75), or »found« (p. 76), when speaking about their supposed application in different texts, but also »traced back (to the conclusion rule)« (p. 76) or »based on (conditionals)« (p. 77), when speaking about their possible frames of definitions. How topoi are “based on (conditionals)”, or “traced back (to the conclusion rule)”, and how these operations relate to argument(s) and conclusion(s) that topoi are supposed to connect is not explained.

Consider another interesting example, this time from Discourse of Politics in Action (Wodak 2009, p. 97). In subsection 4.1, Wodak examines the discursive construction of MEP’s identities, especially whether they view themselves as Europeans or not. At the end of the subsection, she summarizes:

Among MEPs[viii] no one cluster characteristics is particularly prominent; however, most MEPs mention that member states share a certain cultural, historical and linguistic richness that binds them together, despite differences in specifics; this topos of diversity occurs in most official speeches (Weiss, 2002). Among the predicational strategies employed by the interviewees, we see repeated reference to a common culture and past (topos of history, i.e. shared cultural, historical and linguistic traditions; similar social models) and a common present and future (i.e. European social model; ‘added value’ of being united; a way for the future). Moreover, if identity is to some extent ‘based on the formation of sameness and difference’ (topos of difference; strategy of establishing uniqueness; Wodak et al., 1993, pp. 36-42), we see this in the frequent referral to Europe, especially in terms of its social model(s), as not the US or Asia (most prominently, Japan).

In trying to reconstruct the “topological” part of this analysis, three topoi are mentioned: topos of diversity, topos of history, and topos of difference. Surprisingly, only the topos of history is listed and (sparingly) explained in the list of topoi on p. 44: “Topos of History – because history teaches that specific actions have specific consequences, one should perform or omit a specific action in a specific situation.” The absence of the other two should probably be accounted for with the following explanation on pages 42-43:

These topoi have so far been investigated in a number of studies on election campaigns (Pelinka and Wodak 2002), on parliamentary debates (Wodak and van Dijk 2000), on policy papers (Reisigl and Wodak 2000), on ‘voices of migrants’ (Krzyzanowski and Wodak 2008), on visual argumentation in election posters and slogans (Richardson and Wodak forthcoming), and on media reporting (Baker et al. 2008).

But in the study “on visual argumentation in election posters and slogans”, for example, the(se) topoi are not discussed at all; they are presented as a fixed list of names of topoi, without any explanation of their functioning, while the authors (Richardson and Wodak) make occasional reference to their names – and not to the mechanism of their functioning – just as Wodak does in the above example from The Discourse of Politics in Action.

Therefore, if a topos is to serve the purpose of connecting an argument with a conclusion, as the respective works emphatically repeat, one would expect at least a minimal reconstruction, but there is none. What we have could be described as referring to topoi or evoking them or simply mentioning them, which mostly seems to serve the purpose of legitimating the (already) existing discourse and/or text analysis, but gives little analytical- or theoretical-added value in terms of argumentation analysis.

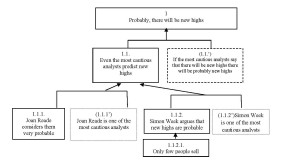

When I speak of reconstruction, what I have in mind is at least a minimal syllogistic or enthymemetic structure of the following type. As an example, I am using another topic from The Discourse of Politics in Action (Wodak 2009, pp.132-142), namely the problem of EU enlargement, as discussed among MEPs:

1. If a specific action costs too much money, one should perform actions that diminish the costs. (Topos connecting argument with conclusion)[ix]

2. EU enlargement costs too much money. (Argument)

3. EU enlargement should be stopped/slowed down … (Conclusion)

5. Back to the foundations: Aristotle and Cicero

It is quite surprising that none of the quoted works even mention the origins of topoi, their extensive treatment in many works and the main authors of these works, namely Aristotle and Cicero. As mentioned earlier, the definition, borrowed from Kienpointner (mostly on a copy-paste basis), does not stem from Aristotle or Cicero either: it is a hybrid product, with strong input from Stephen Toulmin’s work The Uses of Argument, published in 1958. According to Aristotle, as with many of his commentators, topoi are supposed to be of two kinds: general or common topoi, appropriate for use everywhere and anywhere, regardless of situation, and specific topoi, in their applicability, limited mostly to the three genres of oratory (judicial, deliberative, and epideictic). Or, as Aristotle (Rh. 1358a31-32, 1.2.22) puts it: “By specific topics I mean the propositions peculiar to each class of things, by universal those common to all alike”

The Aristotelian topos (literally: “place”, “location”) is an argumentative scheme, which enables a dialectician or rhetorician to construe an argument for a given conclusion. The majority of Aristotle’s interpreters see topoi as the (basic) elements for enthymemes, the rhetorical syllogisms[x]. The use of topoi, or loci, as the Romans have called them, can be traced back to early rhetoricians (mostly referred to as sophists) such as Protagoras or Gorgias. But while in early rhetoric topos was indeed understood as a complete pattern or formula, a ready-made argument that can be mentioned at a certain stage of speech (to produce a certain effect, or, even more important, to justify a certain conclusion), most of the Aristotelian topoi are general instructions allowing a conclusion of a certain form (not content), to be derived from premises of a certain form (not content). That is why Aristotle could present them as a “list” (though it really was not a list in the sense DHA is using the term): because they were so very general, so very basic, that they could have been used in every act of speech or writing. This is not the case with the DHA lists of topoi we have been discussing above: these topoi cannot be used in just any situation, but in rather particular situations, especially the topoi “identified” by Krzyzanowski. They could be classified not as common topoi, but more likely as specific topoi, something Aristotle called idia, which could be roughly translated as “what is proper to…”, “what belongs to…”. Also, this “list” of Aristotle’s common topoi was not there for possible or prospective authors “to check their arguments against it”. This “list” was there for general use, offering a stock of possible and potential common topoi for possible and potential future arguments and speeches.

5.1. Some basic definitions

Here is a short schematic and simplified overview of how Aristotle defines the mechanics and the functioning of topoi and their parts in his Topics, a work that preceded Rhetoric. We have to start with a few definitions.

Problems – what is at stake, what is being discussed – are expressed by propositions. Every proposition consists of a subject and predicate(s) that belong(s) to the subject. These predicates, usually referred to as predicables, are of four kinds: definition, genus, property, and accident:

Definition is a phrase indicating the essence of something. (T. I. v. 39-40)

A genus is that which is predicated in the category of essence of several things, which differ in kind. (T. I. v. 32-33)

A property is something, which does not show the essence of a thing but belongs to it alone and is predicated convertibly of it. (T. I. v. 19-21)

An accident is that which is none of these things … but still belongs to the thing. (T. I. v. 4-6)

These are the theoretical and methodological preliminaries that lead us to topoi, not yet the topoi themselves! To be able to select subject appropriate claims, premises for concrete context-dependent reasonings from the pool of potential propositions, we need organa or tools. Aristotle distinguishes four:

The means by which we shall obtain an abundance of reasonings are four in number:

1. the provision of propositions,

2. the ability to distinguish in how many senses a particular expression is used,

3. the discovery of differences and 4) the investigation of similarities. (T. I xiii. 21-26)

Strictly speaking, we are not yet dealing with topoi here, though very often and in many interpretations[xi] the four organa, as well as the four predicables, are considered to be topoi (and in the case of predicables, maybe even the topoi).

In the Topics, Aristotle actually established a very complex typology of topoi with hundreds of particular topoi: about 300 in the Topics, but just 29 in the Rhetoric[xii]. Two of the most important sub-types of his typology, sub-types that were widely used throughout history, are:

a. topoi concerning opposites, and

b. topoi concerning semantic relationships of “more and less”.

For an understanding of how topoi are supposed to function, here are two notorious examples:

Ad a)

If action Y is desirable in relation to object X, the contrary action Y’ should be disapproved of in relation to the same object X.

This is a topos, as Aristotle would have formulated it. And what follows is its application to a concrete subject matter that can serve as a general premise in an enthymeme (topos cannot):

“If it is desirable to act in favour of one’s friends, it should be disapproved of to act against one’s friends.”

Ad b)

If a predicate can be ascribed to an object X more likely than to an object Y, and the predicate is truly ascribed to Y, then the predicate can even more likely be ascribed to X.

Once more, this is a topos. And what follows is its application to a concrete subject matter that can serve as a general premise in an enthymeme (topos cannot):

“Whoever beats his father, even more likely beats his neighbour.”

We should now be able to distinguish two ways in which Aristotle frames topoi in his Topics. Even more, topoi in the Topics would usually be twofold; they would consist of an instruction, and on the basis of this instruction, a rule would be formulated. For example:

1. Instructions (precepts): “Check whether C is D.”

2. Rules (laws): “If C is D, then B will be A.”

Instructions would usually check the relations between the four predicables (definition, genus, property, accident), and, subsequently, a kind of rule would be formulated that could – applied to a certain subject matter – serve as a general premise of an enthymeme.

What is especially important for our discussion here, i.e. the use of topoi in critical discourse analysis, is that though they were primarily meant to be tools for finding arguments, topoi can also be used for testing given arguments. This seems to be a much more critical and productive procedure than testing hypothetical arguments “against the background of the list of topoi”. But in order to do that, DHA analysts should:

1. clearly and unequivocally identify arguments and conclusions in a given discourse fragment,

2. show how possible topoi might relate to these arguments.

In the DHA works quoted in the first part of this article, neither of the two steps was taken.

This is how topoi were treated in the Topics. But when we turn from the Topics to the later Rhetoric, we are faced with the problem that the use and meaning of topos in Aristotle’s Rhetoric is much more heterogeneous than in the Topics. Beside the topoi complying perfectly with the description(s) given in the Topics, there is an important group of topoi in the Rhetoric, which contain instructions for arguments not of a certain form, but with a certain concrete predicate, for example, that something is good, honourable, just, etc.

With the Romans, topoi became loci, and Cicero literally defines them as “the home of all proofs” (De or. 2.166.2), “pigeonholes in which arguments are stored” (Part. Or. 5.7-10), or simply “storehouses of arguments” (Part. Or. 109.5-6). Also, their number was reduced from 300 in Topics or 29 in Rhetoric to up to 19, depending on how we count them.

Although Cicero’s list correlates pretty much, though not completely, with Aristotle’s list from the Rhetoric B 23, there is a difference in use: Cicero’s list is considered to be a list of concepts that may trigger an associative process rather than a collection of implicit rules and precepts reducible to rules, as the topoi in Aristotle’s Topics are. In other words, Cicero’s loci mostly function as subject matter indicators and loci communes[xiii]. Or, in Rubinelli’s words (2009, p. 107):

A locus communis is a ready-made argument that, as Cicero correctly remarks, may be transferable (…) to several similar cases. Thus, the adjective communis refers precisely to the extensive applicability of these kind of arguments; however, it is not to be equated to the extensive applicability of the Aristotelian topoi /…/. The latter are “subjectless”, while the former work on a much more specific level: they are effective mainly in juridical, deliberative and epideictic contexts.

But being ready-made, does not mean that they prove anything specific about the case that is being examined, or that they add any factual information to it. As Rubinelli puts it (2009, p. 148):

… a locus communis is a ready-made argument. It does not guide the construction of an argument, but it can be transferable to several similar cases and has the main function of putting the audience in a favourable frame of mind.

This brings us a bit closer to how topoi might be used in DHA. In the works quoted in this paper, the authors never construct or reconstruct arguments from the discourse fragments they analyse – despite the fact that they are repeatedly defining topoi as warrants connecting arguments with conclusions; they just hint at them with short glosses. And since there is no reconstruction of arguments from concrete discourse fragments under analysis, hinting at certain topoi, referring to them or simply just mentioning them, can only serve the purpose described by Rubinelli as “putting the audience in a favourable frame of mind.” “Favourable frame of mind” in our case – the use of topoi in DHA – would mean directing a reader’s attention to a “commonly known or discussed” topic, without explicitly phrasing or reconstructing possible arguments and conclusions. Thus, the reader can never really know what exactly the author had in mind and what exactly he/she wanted to say.

6. Topoi, 2000 years later

Let us jump from the old rhetoric to the new rhetoric now, skipping more than 2000 years of degeneration of rhetoric, as Chaim Perelman puts it in his influential work Traité de l’argumentation – La nouvelle rhétorique.

Topoi are characterised by their extreme generality, says Perelman (1958/1983, pp.112-113), which makes them usable in every situation. It is the degeneration of rhetoric and the lack of interest for the study of places that has led to these unexpected consequences where “oratory developments” against fortune, sensuality, laziness, etc. – which school exercises were repeating ad nauseam – became qualified as commonplaces (loci, topoi), despite their extremely particular character. By commonplaces we more and more understand, Perelman continues, what Giambattista Vico called “oratory places”, in order to distinguish them from the places treated in Aristotle’s Topics. Nowadays, commonplaces are characterised by banality, which does not exclude extreme specificity and particularity. These places are nothing more than Aristotelian commonplaces applied to particular subjects, concludes Perelman. That is why there is a tendency to forget that commonplaces form an indispensable arsenal in which everybody who wants to persuade others should find what he is looking for.

And this is exactly what seems to be happening to the DHA approach to topoi as well. Even more, the works quoted in the first part of the article give the impression that DHA is not using the Aristotelian or Ciceronian topoi, but the so-called »literary topoi«, developed by Ernst Robert Curtius in his Europaeische Literatur und Lateinisches Mittelalter (1990, pp. 62-105, English translation). What is a literary topos? In a nutshell, already oral histories passed down from pre-historic societies contain literary aspects, characters, or settings, which appear again and again in stories from ancient civilisations, religious texts, art, and even more modern stories. These recurrent and repetitive motifs or leitmotifs would be labelled literary topoi. “They are intellectual themes, suitable for development and modification at the orator’s pleasure“, argues Curtius (1990, p. 70). And topoi is one of the expressions Wodak is using as synonyms for leitmotifs (2009, p. 119):

“In the analysis of text examples which were recorded and transcribed I will first focus on the leitmotifs, which manifest themselves in various ways: as topoi, as justification and legitimation strategies, as rules which structure conversation and talk, or as recurring lexical items …”

This description and definition may well be dismissed as very general or superficial, but in The Discursive Construction of National identity, where 49 topoi are listed (without any pattern of functioning[xiv]), we can also find (p. 38-39) locus amoenus (topos of idyllic place) and locus terribilis (topos of terrible place). These two topoi have absolutely nothing to do with connecting arguments to conclusions, but are literary topoi per excellence, formulated and defined by E. R. Curtius[xv]. To clarify this: there is nothing wrong with literary topoi, their purpose just is not connecting possible arguments to possible conclusions.

For the New Rhetoric (Perelman/Olbrechts-Tyteca1958/1983, p. 113) topoi are not defined as places that hide arguments, but as very general premises that help us build values and hierarchies, something Perelman, whose background was jurisprudence, was especially concerned about.

Perelman has made some very interesting and important observations regarding the role and the use of topoi in contemporary societies. He argued that (Perelman/Olbrechts-Tyteca1958/1983, p. 114) even if it is the general places that mostly attract our attention, there is an undeniable interest in examining the most particular places that are dominant in different societies and allow us to characterize them. On the other hand, even when we are dealing with very general places, it is remarkable that for every place we can find an opposite place: to the superiority of lasting, for example, which is a classic place, we could oppose the place of precarious, of something that only lasts a moment, which is a romantic place.

And this repartition gives us the possibility to characterize societies, not only in relation to their preference of certain values, but also according to the intensity of adherence to one or another member of the antithetic couple.

This sounds like a good research agenda for DHA, as far as its interest in argumentation is concerned: to find out what views and values are dominant in different societies, and characterize these societies by reconstructing the topoi that underlie their discourses. But in order to be able to implement such an agenda – an agenda that is actually very close to DHA’s own agenda – DHA should dismiss the list of prefabricated topoi that facilitates and legitimizes its argumentative endeavour somehow beforehand (i.e. the topoi are already listed, we just have to check our findings against the background of this list of topoi), and start digging for the topoi in concrete texts and discourses. How can DHA achieve that?

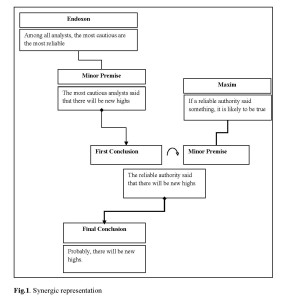

7. Toulmin: topoi as warrants

Curiously enough, the same year that Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca published their New Rhetoric, Stephen Toulmin published his Uses of Argument, probably the most detailed study of how topoi work. I say “curiously enough” because he does not use the terms topos or topoi, but the somewhat judicial term “warrant”. The reason for that seems obvious: he is trying to cover different “fields of argument”, and not all fields of argument, according to him, use topoi as their argumentative principles or bases of their argumentation. According to Toulmin (1958/1995, pp. 94-107), if we have an utterance of the form, “If D then C” – where D stands for data or evidence, and C for claim or conclusion – such a warrant would act as a bridge and authorize the step from D to C (which also explains in more detail where Manfred Kienpointner’s definition of topos draws from). But then a warrant may have a limited applicability, so Toulmin introduces qualifiers Q, indicating the strength conferred by the warrant, and conditions of rebuttal (or Reservation) R, indicating circumstances in which the general authority of the warrant would have to be set aside. And finally, in case the warrant is challenged in any way, we need some backing as well.

It is worth noting that in Toulmin’s diagram, we are dealing with a kind of “surface” and “deep” structure: while data and claim stay “on the surface”, as they do in everyday communication, the warrant is – presumably because of its generality – “under the surface” (like the topos in enthymemes), and usually comes “above the surface” only when we try to reconstruct it. And how do we do that, how do we reconstruct a warrant?

What is attractive and useful about Toulmin’s theory is the fact that he is offering a kind of a guided tour to the centre of topoi in six steps, not just in three (as in enthymemes). All he asks is that you identify the claim or the standpoint of the text or discourse you are researching, and then he provides a set of five questions that lead you through the process.

If we revisit our semi-hypothetical example with the topos of actual costs of enlargement (Wodak 2009, pp. 132-142):

1. If a specific action costs too much money, one should perform actions that diminish the costs. (Topos connecting argument with conclusion)

2. EU enlargement costs too much money. (Argument)

3. EU enlargement should be stopped/slowed down… (Conclusion)

and expand it into the Toulmin model, we could get the following:

Claim: EU enlargement should be stopped/slowed down …

What have you got to go on?

Datum: EU enlargement costs too much money.

How do you get there?

Warrant: If a specific action costs too much money, one should perform actions that diminish the costs.

Is that always the case?

Rebuttal: No, but it generally/usually/very often is. Unless

there are other reasons/arguments that are stronger/

more important … In that case the warrant does not apply.

Then you cannot be so definite in your claim?

Qualifier: True: it is only usually… so.

But then, what makes you think at all that if a specific action costs too much money one should perform actions …

Backing: The history of the EU shows…

If the analysis (text analysis, discourse analysis) would proceed in this way[xvi] – applying the above scheme to concrete pieces of discourse each time it wants to find the underlying topoi – the lists of topoi in the background would become unimportant, useless, and obsolete. As they, actually, already are. Text mining, to borrow an expression from computational linguistics, would bring the text’s or discourse’s own topoi to the surface, not the prefabricated ones. Even more, Toulmin’s scheme allows for possible exceptions, or rebuttals, indicating where, when, and why a certain topos does not apply. Such a reconstruction can offer a much more complex account of a discourse fragment under investigation than enthymemes or static and rigid lists of topoi.

8. In place of conclusion

If DHA really wants to follow the principle of triangulation, as described in the beginning of the article, to make choices at each point in the research itself, and at the same time make these choices transparent, taking all these steps in finding the topoi in concrete texts would be the only legitimate thing a credible and competent analysis should do. If DHA wants to incorporate argumentation analysis in its agenda, that is, not just references to the names of concepts within argumentation analysis.

NOTES

[i] The complete and more detailed version of the paper can be found in Lodz papers in Pragmatics, vol. 6, n. 1/2010. Electronic version is available at: http://versita.metapress.com/content/v4477v71x19p/?p=f734650e911642299c0c906ff9982d14&pi=0.

[ii] Apart from the italicized use of topoi as terminus technicus all emphases (italics) in the article are mine (IŽŽ).

[iii] It should be noted that Kienpointner’s definition is a hybrid one, grafting elements from Toulmin (1958) onto Aristotelian foundations.

[iv] The paper was recently published in Critical Discourse Studies 6/4 (2009), under the title “Recontextualising fascist ideologies of the past: right-wing discourses on employment and nativism in Austria and the United Kingdom”. In this article, I am referring to the manuscript version.

[v] Let alone the fact that there is no theoretical explanation why there should be lists at all, or how we should proceed when checking the possible argument schemes “against the background of the list of topoi”.

[vi] These lists may look like recipes, but this is the way the authors present them.

[vii]It is interesting to observe that in his plenary talk at the CADAAD 2008 conference (University of Hertfordshire), Teun van Dijk emphasized: “CDA is not a method, CDA is not a theory … CDA is like a movement, a movement of critical scholars.” But then he added: “And they will use all the methods we know in various domains and schools of discourse analysis (see: http://www.viddler.com/explore/cadaad/videos/4/; 5th and 6th minute).” “Anything goes” should therefore be interpreted and understood in a much more narrow sense, namely, as “any method goes”. In other words, if a particular scholar or a particular school is using a certain method, the rules and principles of this chosen method should be followed.

[viii] Members of the European Parliament (IŽŽ).

[ix] It is worth noting that each topos can usually have two “converse” forms, and several different phrasings. Therefore the phrasing of this topos could also read: “If a specific action costs too much money, this action should be stopped”, depending on the context, and/or on what we want to prove or disprove (i.e. put forward as an argument).

[x] An important and more than credible exception in this respect is Sara Rubinelli with her excellent and most thorough monograph on topoi, Ars Topica. The Classical Technique of Constructing Arguments from Aristotle to Cicero, Argumentation Library, Springer, 2009.

[xii] See Rubinelli 2009, pp. 8-14.

[xii] The 29 topoi in the Rhetoric cannot all be found among the 300 topoi from the Topics. There is a long-standing debate about where these 29 topoi come from, and how the list was composed. Rubinelli (2009, pp. 71-73) suggests that their more or less “universal applicability” may be the criterion.

[xiii] This is probably due to the fact that Cicero was selecting and using loci in conjunction with the so-called stasis theory, or issue theory. What is stasis theory? Briefly and to put it simply, the orator has to decide what is at stake (why he has to talk and what he has to talk about): 1) whether something happened or not; 2) what is it that happened; 3) what is the nature/quality of what happened; 4) what is the appropriate place/authority to discuss what has happened. And Cicero’s loci “followed” this repartition.

[xiv] Instead, we can read (p. 34): “In place of a more detailed discussion, we have provided a condensed overview in the form of tables, which list the macro-strategies and the argumentative topoi, or formulae, and several related (but not disjunctively related) forms of realization with which they correlate in data.”

[xv] For a succinct description of locus amoenus, see Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Locus_amoenus.

[xvi] Our sample analysis is, of course, purely hypothetical. Concrete analysis would need input from concrete discourse segments.

REFERENCES

Aristotle (1989). Topica (Transl. by E.S. Forster). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Aristotle (1991). Art of Rhetoric (Transl. by J.H. Freese). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Cicero, M. T. (2003). Topica (Transl. by T. Reinhardt). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Curtius, R. E. (1990). European Literature and the Latin Middle Ages. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Fairclough, N. (1995). Critical discourse analysis: the critical study of language. Harlow: Longman.

Fairclough, N. (2000). Discourse and Social Change. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Fairclough, N. (2003). Analysing Discourse. Textual Analysis for Social Research. London/New York: Routledge.

Galasinska, A. & Krzyzanowski, M. (Eds.) (2009). Discourse and Transformation in Central and Eastern Europe. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kienpointner, M. (1992). Alltagslogik. Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt: Frommann-Holzboog.

Krzyzanowsky, M. (2009). On the ‘Europeanisation’ of Identity Constructions in Polish Political Discourse after 1989. In: A. Galasinska & M. Krzyzanowski (Eds.), Discourse and Transformation in Central and Eastern Europe (pp. 95-113), Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Perelman, C. & Olbrechts-Tyteca, L. (1983). Traité de l’argumentation. La nouvelle rhétorique. Bruxelles: Editions de l’Université de Bruxelles.

Reisigl, M. & Wodak, R. (2001). Discourse and Discrimination. Rhetoric of Racism and Antisemitism. London/New York: Routledge.

Richardson, J. E. (2004). (Mis)Representing Islam: the racism and rhetoric of British Broadsheet newspapers. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Richardson, J. E. & Wodak, R. (2008). The impact of visual racism: Visual arguments in political leaflets of Austrian and British far-right parties. (Manuscript. Paper presented at the 2008 Venice Argumentation Conference).

Rubinelli, S. (2009). Ars Topica. The Classical Technique of Constructing Arguments from Aristotle to Cicero. Berlin: Springer.

Toulmin, S. (1995). The Uses of Argument. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

van Leeuwen, T. (2004). Introducing Social Semiotics. London/New York: Routledge.

van Leeuwen, T. (2008). Discourse and Practice. New Tools for Critical Discourse Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

van Leuween, T. &Kress, G. (2006). Reading Images. The Grammar of Visual Design. London/New York: Routledge.

Wodak, R. (2009). The Discourse of Politics in Action. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Wodak, R. & Chilton, P. (Eds.) (2005). A New Agenda in (Critical) Discourse Analysis. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Wodak, R. & Meyer, M. (Eds.) (2006). Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis. London: Sage.

Wodak, R. & van Dijk, T. (Eds.) (2000). Racism at the Top. Klagenfurt: Drava.

Wodak, R., de Cillia, R., Reisigl, M. and Liebhart, K. (1999). The Discursive Construction of National Identity. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.