Effective PhD Supervision – Chapter Four – Coaching: Charting your own Path

The PhD researcher is immersed in a ‘writing-centred pedagogy’ that requires critique and encouragement from experienced researchers. While writing is central to the research process, so is thinking, imagining and relating. The learning and teaching strategies needed in supervision are varied and complex – even ‘chaotic’! These supervision interactions ideally stretch and support the PhD researcher, whilst enriching and expanding the world of the supervisor. Painted with such broad brush strokes the enterprise promises colour and boldness – but it also requires finesse, detailed attention and precision of focus.

An interesting parallel to the qualities needed in the research journey are those needed by accomplished scientists. Fensham, in interviews with leading scientists in China, distinguishes the characteristics needed to succeed in both independent research and in science. These include (in order of priority): creativity, personal interest in the topic, perseverance, desire to inquire, ability to communicate, social concern and team spirit. It is particularly these qualities, on the one hand, that mentoring and coaching focus on. Supervision, on the other hand, takes greater responsibility for the formal managing of the degree process, quality checking and teaching. Whilst workshops and programmes for PhD students usually provide formal training in the academic content towards thesis production, mentoring and coaching fosters qualities essential in a scientist, researcher and intellectual. A holistic approach takes into account the complexity of a large research project.

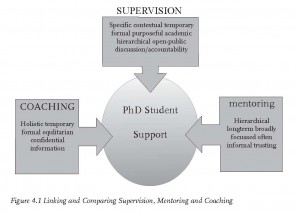

The diagram below shows the contrasting features of supervision, coaching and mentoring. Note that the student is placed at the centre – appropriate to a student-centred pedagogy.

Note: Neither mentoring nor coaching (nor indeed supervision) touches on therapy; neither deals with pathology, psychological analysis, nor with trauma counselling. It is of course, essential to be able to refer students to appropriate professionals should serious problems arise.

Figure 4.1 Linking and Comparing Supervision, Mentoring and Coaching

If I need a ‘how-to’ book – should I be doing a PhD?

By definition a PhD thesis is a unique and original piece of work. PhD students are guided, obviously, but must eventually chart their own path. After some time the emerging experts need to find their own voice, make their own decisions, be prepared to take risks, extend the conventions and eventually outgrow their supervisors. At this point of independence the map for a student becomes vague or the GPS that has been so trusty can only intone ‘recalculating, recalculating’. There is a limit to the use of a road map in work that charts new landscapes. This is a developing paradox that students and supervisors face; and the same is true for ‘Advice books’.

Furthermore, the implication of a ‘how-to’ approach is that there is ‘a step-by-step’ way to advance; yet a thesis does not proceed in a linear path (Kamler and Thomson, 2008). It can be more like a labyrinth. The illusion in seeing a bound and finished product is that there is somehow a neat and clear progression from the abstract, introduction, purpose, context, research questions, methodology, data, findings and conclusions. We know there are some (often frustrating) administration processes, ethics clearances, literature reviews, proposal revisions, data collection and ‘write-up’: but not neatly in that order. This is not usually, how it works. The research project exists within a context of equipment, finances, appointments, supervisors, weather, travel, politics, change and surprises. Just as research itself takes place within a context, the PhD researcher is in a particular context of life, work, family, colleagues, interests, distractions and constraints. There is also all the invisible processes of thinking, planning, assuming, rethinking, prewriting, journaling, mind-mapping, discussing, despairing, changing direction, learning and changing as a person.

It is probably axiomatic that a supervisor and a mentor play a vital role in the process of producing a thesis and a specialist academic. However, the process is often stressful and, in spite of the guidance from supervisors, many students do not make it. The higher education participation rate for South Africa is a low 15%. Although the rate for other sub-Saharan countries is 5%, Latin America has a substantially better rate at 31%. The average participation rate for North America and Western Europe is 70%. With our low numbers entering postgraduate studies, we need to do all we can to nurture our postgraduate students who have often struggled to reach their level of education and often represent the survivors of a tough system. In South Africa we have 27 PhDs per million of the population compared to 42 in Brazil, and 240 in Australia. Reports indicate that up to 50% of PhD students in the UK and the USA drop out4, and in South Africa that number is even higher. PhD students who take a long time to complete put a strain on a system that lacks supervision expertise.

There is some emerging evidence that coaching can be effective for supervisors, students and for both together (i.e., the relationship).10

Possible reasons for the effectiveness of coaching are that a coach addresses the whole situation and the whole person. As Kamler and Thomson1 observe:

‘… the simultaneous fears and reassurances experienced by doctoral researchers are constructed within wider cultural and institutional processes, not simply in advisory relationships’. (p.512)

In a co-active coaching relationship there is equality between the student researcher (in this case) and the coach. The thesis writing provides an opportunity for self-reflection and personal – not just academic – growth. The coach encourages this broader development. The student may open up to a ‘neutral’ listener who can provide a new perspective on what may be happening. The coach champions the goals of the student, keeps these goals accountable to the goal’s own norms along the way and keeps the goals moving.

In one PhD programme where coaching was included the following features of coaching emerged as critical:

– Providing a neutral environment and an unbiased listener

– Allowing the voicing of taboo subjects (e.g., work relationships/insecurities)

– Acknowledging the student’s aims and ambitions – as well as vulnerability

– Goal setting (for motivation and tracking)

– Strengthening of desirable personal attributes

– Tracking progress and promoting accountability

– Refining self-awareness and reflection.

Outcomes of this PhD coaching programme included developing courage to confront, self-examination, awareness of personal goals, assertiveness and the resolution of boundary issues by taking increased personal responsibility.

The role of the coach is to provide a space conducive for reflection, connection, creativity and action. The dimensions a coach pays attention to are similar to those of a creative organisation (Prather and Gundry, 1995, in Palmer, 2002: 16.). These are:

– Challenge and involvement

– Freedom

– Idea time

– Idea support

– Conflict

– Debates

– Humour and playfulness

– Trust and openness

– Risk taking.

Some of these dimensions are present in coaching and mentoring; some of the outcomes of the PhD programme mentioned above may be achieved in a supervisor and mentor relationship. So what is coaching then?

4.1 What is Coaching?

It has been the task of science to discover that things are very different from what they seem.

Coaching is about discovering and walking different paths. It is a process, formally set up to help student researchers clarify their life purpose, values and goals, and to help them attain these goals in a creative and conscious way. Coaching is not about diagnosis or pathology. Coaching assumes the student researcher to be capable and creative. A coach asks: ‘What’s happening now?’ and ‘What next?’ – rather than: ‘Why?’ A coach works with pressing external issues and personal or team goals. A coaching session is forward-looking and promotes action, aims at helping the student researcher to reach his/her potential and overcome obstacles, looks at the student’s life as a whole rather than the thesis process only, and seeks to deepen awareness of patterns and provides a reflective space. Coaching provides a meta-level of assistance at developing skills of organisation, innovation and reflection. An introductory coaching conversation may sound like this:

Conversation:

Coach: Coaching is not like supervision or mentoring; you need to come up with your own answers.

Student: (Looks perplexed!)

Coach: I will guide you with direct questions and help you clarify your goals. I will also push you to action and hold you accountable.

Student: I don’t know…

Coach: Well, what will coming up with your own answers give you?

4.1.2 Coaching in the context of PhD supervision

The coaching orientation here is directed towards a novice coach, supervisor or mentor wishing to coach a PhD student. Of course, a supervisor could also benefit greatly by having his or her own professional coach. Coaching first gained popularity in executive training and can be adapted for many situations.

Now, just as a supervisor needs specialist expertise, so does a coach; perhaps even more so than does a mentor. An ideal option is for a supervisor or PhD student to have a qualified coach. Such a model is being trialled to a limited extent at some universities. SANPAD is piloting the introduction of coaching for supervisors and students in parallel with mentoring (see Chapter 5).

Although a coach requires specialist training, and the coaching situation is usually a formal arrangement, there are principles of coaching that may be brought in to both supervision and mentoring, or which a student may use alone. This chapter contains an outline of some of these principles and includes exercises. The case studies of Su, Pieter and Thandi illustrate some coaching conversations with PhD students. Also included is a section, Coaching Pathways, to provide a sample overview of what a number of PhD Coaching sessions might look like.

4.2 Aspects of Coaching

4.2.1 Being a coach

Good research should contribute to your development as a mindful person, and your development as an aware and reflective individual should be embodied in your research.

A coach brings deliberate attitudes or meta-perspectives to coaching. Much of the time we show up in a situation, relationship or event in whatever state our internal climate has already dictated. Occasionally we mask these moods by ‘putting on a brave face’, or by playing a professional role, but we seldom consciously think of the quality we would like to contribute or bring to a meeting or function. It can make a surprising impact to go into a presentation or coaching session intending to bring a particular quality such as clarity, joy, humour or calm. This is not an artificial or manufactured mask but an authentic expression of one’s being. The suggestion here is ‘Try it’.

Of course, presenters and leaders often do this instinctively. In a late afternoon session of a long day a facilitator may intentionally try to brighten the atmosphere or create more energy.

The skills of coaching include: listening, intuition, awareness, reflecting back (rephrasing, rewording or mirroring a situation), staying focussed, discovering and reminding the PhD researcher of his values, acknowledging the PhD researcher’s qualities, and linking the current direction to his life-purpose. Unlike a supervisor or mentor, a coach’s own experience or story is irrelevant. A coach needs to restrain herself from telling stories from her own life, from offering advice, or from directing the action of the student researcher. This could be clearly quite a challenge and is not our usual way of interacting. However, in this lies the power of coaching and the empowerment of the student. Yet, coaching is not mechanistic. While the coach is not likely to offer advice, she may offer intuitive insights – or even guesses about the situation!

4.2.2 Designing the coaching relationship

‘How should we do this?’ ‘What do you need from me?’ ‘What can I count on from you?’ ‘How will this relationship work best?’ ‘Let’s discuss and negotiate our needs and wishes, given all the practical constraints here.’

More so than supervision or mentoring, a cornerstone of coaching is confidentiality of discussions. It is also a negotiated and designed relationship. A coach may ask for example: ‘How do you want me to be when you procrastinate?’ or ‘What do you need from this coaching relationship?’

Su unequivocally told me: ‘Nag me! Nag as much as possible: I need that.’ Pieter on the other hand said: ‘I need you to be understanding – I have enough people yelling at me.’ It would probably be unusual for a supervisor to ask a student ‘How would you like me to supervise you?’ Yet Thandi, in our second coaching session, said: ‘Actually I need you to be straight with me: please point out my blind spots. I can take it.’ She also added: ‘I need definite structure. I would like to set up all our meetings for six months, and have you keep me to strict timelines. I need help with organisation.’ As a coach, I need the student researcher to keep appointments, to be real, and to give feedback about how the sessions are going. Coaching sessions address the meta-level of the process as well as the fine details of lining up the trucks. We spend time talking about how we want this relationship to work. We also set up logistics and timeframes.

4.2.3 Paying attention to the creation of a vision

‘- ah, to imagine is to experience the world as it isn’t and has never been, but as it might be.’

Being able to create a vision is a uniquely human capacity. According to Gilbert, however, there is confusion around this. People tend to believe that they have control over uncontrollable events and yet sometimes back away from intervening where they do have control over outcomes, or at least a reasonable chance of influencing events. Gilbert sites various studies that show how gamblers are more convinced of their chances of winning if they can chose their own lottery numbers. I do that too – even while I recognise my foolishness! Yet when I put in a funding grant application, I imagine the chances of success have little to do with me. In his chapter entitled ‘The Joy of Next’, Gilbert claims: ‘The greatest achievement of the human brain is its ability to imagine objects and episodes that do not exist in the realm of the real…’ and ‘…the human brain is an “anticipation machine”.’ Of course it is obvious how handy this skill is in designing research, but it is also to be exploited in encouraging research students’ to see themselves as expert academics and devise steps to get there. However, coaching is not mechanistic; a coach looks out for opportunities to change direction, to transition, and looks for outcomes, but is not attached to particular destinations if circumstances change.

An important part of assisting a student researcher to create a vision is that the vision is unique and personal and ties in with the individual’s values. For one student the research process may need to be conceived of as exciting and adventurous, and include making a difference to political transformation. For another, it might embody values of order, safety and thoroughness. By bringing in personal values and exploring what these might mean in the process, in supervision, in writing and in the establishing of an academic identity, the student’s energy and motivation are enhanced. Tools for facilitating this are included in the following sections.

4.2.4 Perspective: We can choose how we see things

You have brains in your head.

You have feet in your shoes.

You can steer yourself

Any direction you choose.

Of course, we would rather have a sea-view suite than a room in the basement. We would rather our studies were a walk in the park, a piece of cake, a blast! – rather than an up-hill struggle, a battle, a never-ending story or a wandering in the wilderness. By changing our metaphors and our cup half-full or half-empty tendencies we can change our degree of enthusiasm to keep on task. Well, if it was as easy as this, we would all always be energetic and motivated. We know that it is not. A coach can help to offer different ways of seeing a situation and help the student researcher to get in touch with what resonates with an inner agenda or personal life goal. Questions a coach might well ask are:

‘What is the landscape of your life right now?’ ‘In what ways does your research feature on this landscape?’

This results in exploring in a focussed yet open-ended way so as to establish a clearer picture of what is going on.

Another perspective conversation might go like this:

Coach: ‘If your PhD research were a landscape, what would it be?’

Student: ‘An airport: O.R. Thambo airport!’

Coach: ‘Tell me about that.’

Student: ‘It’s a place I know well – but I still get lost there. As I approach, I am filled with anxiety. There are parts that I know and then all the activity, changes, overload of information.’

Coach: ‘It sounds like an overwhelming place. Does it also hold some excitement?’

Student: ‘Yes. It means I am going somewhere. It is a vibey place!’

Coach: ‘In what ways are you “going somewhere” in your research?’

Student: ‘Hmmm …Well, no-one’s done what I’m doing. I don’t know where it will end up. That’s exciting’

… …

The conversation might well follow this metaphor for a while, exploring characteristics and how this relates to research study. The end of the session almost always should lead either to a commitment to action on the part of the student researcher or, otherwise, to an inquiry.

4.2.5 Moving forward

– Action: Definite steps are set – often by the student. The coach will ask for feedback/ confirmation that the task is done (an email, SMS or report back at the next session).

– Homework reflections: these are inquiry questions designed by the coach to promote self-awareness in the student, for example,

Inquiries:

– What is keeping me going?

– What am I saying ‘yes’ to?

– What does it mean to excel?

– Where am I stuck?

– What kind of an academic am I?

Having considered these as a reflection exercise, the student would report on what came up and how this is significant for moving the work forward.

4.2.6 Centredness and focus

Admitting that we do not know and maintaining perpetually the attitude that we do not know the direction necessarily to go permit(s) a possibility of alteration, of thinking, of new contributions and new discoveries, for the problem of developing a way to do what we want ultimately, even when we do not know what we want.

Growth, change, innovation and creativity are dependent on seeing clearly and getting out of a rut. The ability to do this is greatly enhanced by being able to amplify attention to the task in hand: to be in the moment. This a central practice for both coach and the student. By keeping focussed, we have a better chance of seeing what is really going on and what needs to happen next. It is obvious how powerful a practice this is for knowledge creation and research.

This practice in a coaching relationship is often uncomfortable: we seldom really listen to others or to ourselves. We more usually engage in habitual, even ritualised conversations. A coach may sit in silence for a while to allow space for what is difficult to say. Coaching is at its heart a mindfulness practice. A coach tries to be totally present with openness and non-judgement. The difficulty here is letting go of advice, projection and stories. This relates back to a core coaching premise that student researchers are capable of coming up with their own solutions.

4.2.7 Intuition

Sometimes we know without understanding the knowing. Sometimes this knowing is more reliable than that obtained from rigorously analysed data.

Malcolm Gladwell writes a fascinating account of the ‘Statue that didn’t look right’ in Blink. When, in 1983, the J. Paul Getty Museum in California was offered a kouros statue apparently dating from the 6th century BC, scientists spent 14 months verifying its authenticity through electron microscopy, X-ray diffraction, electron microprobe and X-ray fluorescence. One scientist even published a paper in Scientific American on the extraordinary find. The museum agreed to pay $10 M for the statue. In the meantime, various artists who viewed the work exclaimed within seconds that it did not look right; it looked ‘fresh’, and they certainly would not buy it. It turned out that their intuition was correct: the kouros was a fake! This helps to illustrate the power of different ways of knowing that we do not always use – especially in our professional work. A coach is encouraged to get in touch with intuition and use it to shed light on what is happening with the person being coached.

A coach may offer: ‘It seems that there is something else happening here apart from the time constraints you mention.’ Sometimes the ‘hunch’ may be quite specific. When designing a relationship with the student researcher, the coach explains the use of intuition – and asks permission to blurt out possible insights. These need to then be checked and, if they are off the mark, they are simply dropped. This exploratory openness is part of the coaching dynamic that allows for: tentative answers, making mistakes, taking risks, thinking out of the box, and for the student to also take over control and redirect discussions.

4.2.8 Reflective meta-perspective: ‘telling it like it is’

‘It looks to me like this thesis is not a priority for you.’

A coach needs to articulate what is happening, or at least offer a reflection of how things appear – without judging. Making such a statement as the one above might be difficult for a supervisor. There is the hierarchical relationship and quality judgement – but for a coach there is an agreement of being a friend who can be frank and help explore the un-named agendas, saboteurs, cover-ups and unconscious tendencies! As mentioned under ‘intuition’, this is done respectfully, with the student offering counter observations, declining to discuss, or expressing willingness to explore what is going on.

This may also be considered as giving feedback. In supervision, feedback is usually about the text or research process. In coaching, the feedback is holistic. It is often reflective: ‘I noticed you started drooping in your chair when you mentioned the up-coming seminar. It seems there is a heaviness about that.’ Such feedback opens up the opportunity to discuss something that might have been glossed over or that the student may not even have been aware of.

4.2.9 Relationships

‘We all live our lives in a sea of connections.’

Individual coaching has the limitation of not directly including others in the PhD process, even though they are inextricably connected to the PhD researcher and thus to the process. It is therefore sometimes helpful to consider coaching a ‘relationship’ or team. Coaching can be useful for a research team, for a supervisor and student together, or for a research student and his or her partner. This relationship coaching is not therapy; it helps to find a way of co-creating a path and a way of working that is constructive and fulfilling for the team. In the process we acknowledge that we create ourselves and our futures through interconnections. The same principles – of making actions conscious and choosing how we want to be – are core to relationship coaching.

A coach can explore questions with two or more people together:

‘What is important here?’

‘What’s getting in the way?’

‘How do we want to be with each other when things get tough?’

‘What can we count on from each other?’

‘What will make this partnership flourish?’

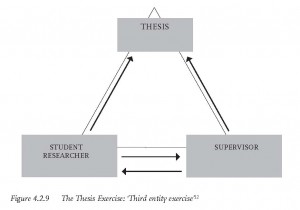

Seeing the situation from the other perspective: the concept here and the accompanying exercise are based on the assumption that the PhD thesis is an ‘entity’ in itself. We habitually view the world from our perspective only; we are encouraged here to see our research from both the point of view of the student, from the point of view of the supervisor and the ‘view’ of the thesis itself.

Figure 4.2.9 The Thesis Exercise: ‘Third entity exercise’12

A coaching example of this is given in the section ‘Coaching Pathways’.

4.2.10 Giving Feedback

By receiving insightful assessment on our qualities, ways of interacting, values, or path of action, we understand how we are perceived by others. Such feedback also helps us to reflect, adjust and grow. In coaching, feedback is expected from both coach and student researcher. Feedback needs to be specific and needs to provide suggestions as to how the coaching or action could be more effective. For example, a coach may ask: ‘In what ways is the coaching helping you? How could it be more effective?’ A student being coached may ask: ‘What do you see that I am not aware of?’ It is clear from this last question that the student needs to be aware of the ‘rules-of-the-game’ of coaching. It is part of the coach’s task to train the student in the goals and principles of coaching.

Positive feedback is part of the fabric of a coaching relationship. Acknowledging the qualities and achievements of the coachee helps build confidence, self-esteem, self awareness and motivation. Perhaps because ‘critical thinking’ is so valued in academia, we tend to become easily critical and can forget to acknowledge the positive. It is not unusual for a student or academic to go for years without anyone giving them confirmation that they are ‘insightful, bright, dedicated, determined…’ and so forth. Considering how much criticism a PhD researcher is subjected to, there is often a gradual eroding of a student’s confidence. A coach is encouraged to give the student acknowledgement every coaching session. If only one aspect of coaching for PhD supervision were to be taken up, acknowledging the student researcher would be the most constructive and effective!

4.3 Coaching Pathways

In this section a possible outline of a series of eight coaching sessions will be presented. Obviously, many of the coaching skills may be integrated subtly or explicitly into any supervisory meeting, they can also be used as appropriate in varying order in coaching sessions. The session layout is not quite a ‘literal’ guide to the process. It is clear that follow-up from previous sessions is necessary – and this may take the coaching in completely different directions. The ‘menu’-type layout presented here is meant to give an overview of how coaching may work over time. The assumption here is that these processes are less familiar than supervisory sessions where PhD researcher and supervisor are discussing research progress. The outline is, however, condensed and is provided for supervisors who have participated in mentoring and coaching training. This chapter is premised on the assumption that the supervisor or student researcher has some familiarity with co-active coaching processes. In Session 8 of the Pathways, there are some suggestions for using creative writing for coaching. This aspect has the advantage of also serving as a self-coaching tool.

4.3.1 Session 1: Building a relationship

– Introduction

Explain briefly the principles of coaching; how it differs from supervision, mentoring and therapy. Discuss the ethics of confidentiality. (See ‘Introduction to Coaching Form’ in Templates)

– Find out about the student

Note that ‘story lines’ are always kept to a minimum in coaching (unlike therapy).

– Design the coach-student partnership: set up agreements

Discuss (quite frankly) what kind of relationship this will be and what will make it work. Set up logistics for meeting times, accountability and number of sessions.

– Discuss the aims of coaching

A new student requires training on how to be coached. This is often a new way of relating. A coach seeks permission to challenge, push, inquire and make it clear that all this is negotiable in a relationship that seeks to be equal and democratic. Coaches keep their own experience out of the picture (This is hard to do!) and they expect a student researcher to come up with their own solutions. Like most rules, of course, this one is also broken: at times the coach may ask: ‘Will you have the next two chapters completed by next week?’

4.3.2 Session 2: Values

– What are the student’s values? Ask the PhD researcher about a Critical Incident when he or she felt in control or striding forwards, etc. Sharing such experiences amplifies the event and serves as a model to reveal qualities and values. Note down the values you, as a coach, see in the situation and ask the students what values they see. Spend time discussing and clarifying these values. Helpful questions to elicit values include:

– What is present when you are at your best?

– How would you like to be in the world?

– What is your unique contribution?

– What is the role of our own gremlins? Discuss how we sabotage ourselves.

– What are the negative inner commentaries regarding the PhD research?

– What gets in the way?

The Yogic sages say that all the pain of a human life is caused by words, as is all joy. We create words to define our experience and those words bring attendant emotions that jerk us around like dogs on a leash. We get seduced by our own mantras (I’m a failure … I’m lonely … ) …

Saboteur myths

– Suffering is inevitable

– Worry is warranted

– It’s not good enough

– Anxiety has value

– More is better

– Guilt is deserved

– I will do bad work and look like an idiot

– I can’t

– It’s all too much

– There’s no time

– It’s not fair

– Not again

– I’ll start next week

– I’ve got too much to do

– They don’t give me space/time/conducive conditions…

A homework inquiry for the student may be:

‘What am I withholding?’

‘What do I resent?’

‘What do I regret?’

Ask the student to draw their gremlin(s) and give it/them a name.

– Acknowledge the student

4.3.3 Session 3: Where are you now?

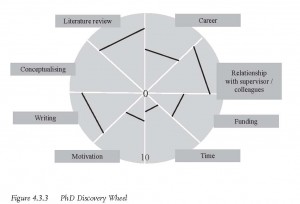

– Discover the level of achievement in aspects of study and life: Discovery Wheel.

The student researcher rates his/her perceived level of achievement/satisfaction with the aspects presented in the wheel.

The coach probes what the scores (out of ten) mean for the student.

Choose an aspect of the wheel to work on.

Ask direct/powerful questions, such as, ‘What would a 10/10 mean for you in your career?’

Give an inquiry or task for homework, or ask the student to come up with a follow-up activity.

Figure 4.3.3 PhD Discovery Wheel (A completed wheel may look like this:)

‘What surprises you about this?’

‘What would a ten look like for you as far as writing goes?’

‘Who can help you?’

Ask the student to come up with suggestions for action to move forward in one of the aspects. Set tasks and accountability.

4.3.3 Session 4: Practicing Focus

– Clear anything that might be in the way of a session. Spend only two minutes on this. For example: ‘What do we need to get out the way for you to arrive on time?’ (Student grumbles about being stuck in traffic or marking, etc.)

– Check homework accountability.

– Choose a small current aspect to work on: ‘What about this is important to you?’

– Build intrinsic motivation: ‘What thrills you?’ ‘What is compelling about this?’

– Establish accountability: ‘What will you do next?’ ‘When will you do it?’ and ‘How will I know?’

4.3.4 Session 5: Perspective

Keeping a balance in one’s life is not easy most of the time – never mind amongst the pressures of PhD research.

– Start from where we are: where’s here? How does it feel? Connect with the body. Settle and take time to be present. ‘What’s happening now?’

What perspective does the student researcher have on a particular aspect of the PhD or the whole process? Name or use a metaphor for this attitude/perspective. An example would be: ‘As far as the literature review is concerned I feel like I am lost in a maze.’

(It is helpful to move around for this exercise.)

Then, physically move to a different perspective: ‘What is the “seeing as far as the horizon” perspective like?’ – ask this while looking out the window, standing next to the student. Check out this perspective. ‘What does this feel like?’

Find another perspective: for example, move to staring at the book-case. ‘What does the book-case perspective feel like?’ Ask the student researcher to choose the perspective that feels best. Physically move to that perspective. Get a feeling for it. Move on to designing a way forward and setting up tasks.

– Acknowledge the student

4.3.5 Session 6: Fulfilment

Discover the Dream

– What is compelling about the research?

– What is compelling about being an academic?

What would your future self say?

A vision exercise of picturing yourself as a PhD doctor. Take time to talk through this vision.

– ‘Who have you become?’

– ‘Where are you in this situation?’

– ‘What advice does your future self give you?’

– ‘What is the next step?’

Set tasks and accountability.

– Acknowledge the student

4.3.7 Session 7: Relationship/team coaching

Ask the student researcher to describe a relationship with the supervisor and with the thesis.

(Refer to the triad diagram, Figure 4.2.9)

Ask the student researcher to move to another chair and describe how things look from the supervisor’s perspective. Then ask the student to move to a third position, that of the thesis, and describe how things look from the perspective of the thesis itself. (This sounds very strange but can be surprisingly effective!)

‘What is trying to happen here?’

Find actions that support new insights that arise from this.

4.3.6 Session 8: Coaching through creative writing

We have already considered the role of creativity (which deserves considerable attention in research as a high level of cognitive skill). It is worth noting some of the obstacles to creativity before engaging in this coaching through writing. Gundry (1995) lists four stumbling blocks which are no doubt familiar to us:

– Judging ideas too quickly

– Stopping at the first good idea

– Failing to ‘get the bandits off the train’

– Obeying rules that don’t exist.

One of the ways over these obstacles is to free-write. Set this as an exercise.

4.3.8.1 Self-reflection free-writing

Free-writing is a way to get over writer’s block, to discover one’s own voice, clarify thought and to simply keep the writing and thinking processes going. The only rule in free-writing is: not to stop writing! Invite a student to complete a sentence such as this: (set a time for writing, e.g., 4 minutes.)

The thing about being a PhD researcher is ……………………….……………………….…………

Or:

What uncommon questions cross your mind? Write a list of these.

………………….…………………….……………………….……….……………………….……………………………….…………..

…………………….………………………….……………………………….………………………..……………….…………………..

………………….……………………….…………….……….……………………….………………………………….………………..

In research we need not only to note what is there, but what is not there; what people are not saying; what questions are not being asked.

We note forms. We often miss the spaces between.

Write about the formless in your thinking:

…………………………………………………………….……………………….……………………………………………………

String theory; particles; excited electrons: we can hardly talk in any discipline, including science without the use of metaphor.

Use a metaphor to free-write about your research project. (Do not think about this – simply free-write!)

– My PhD is like a …….….………………………….….……………………

4.4 Conclusions

This section was intended for those who have some coaching experience. It has attempted to show how coaching skills and principles may be integrated into supervision. If even some of these ideas are tried out, the supervision-student relationship is likely to be enriched and enlivened.

—-

Next Chapter – Chapter Five: http://www.rozenbergquarterly.com/?p=1928