Effective PhD Supervision – Chapter Five – The Relationship between PhD Candidate and Supervisor

5.1 Styles of Supervisor-Candidate Relationships: A typology

5.1 Styles of Supervisor-Candidate Relationships: A typology

5.1.1. Introduction

Every PhD supervisor is different and every PhD candidate as well. Hence, relationships between a supervisor and a PhD candidate are full of idiosyncrasies and peculiarities. Many are the stories about strange professors, with odd habits, and full of eccentricity. And among professors, memories of strange misunderstandings with their PhD candidates form part of their discussions over drinks. However, there is order in this chaos. In a number of SANPAD supervisory workshops in South Africa, and in Ceres training courses in the Netherlands, we experimented with an approach in which a typology was designed of possible relationships. Participants in these workshops were then first asked to position their own relationship with their former PhD supervisor in this typology. As a second step they were asked to do the same with each of their prior and current PhD supervision relationships. And, indeed, there appeared to be order in the chaos, but with a lot of comments. Let us first look at the typology as such.

5.1.2 Styles of Supervision

In discussing styles of supervision there are the following important variables:

– Relationship behaviour: businesslike or personal

– Task behaviour: commitment (more/less) and product or process orientation

Businesslike behaviour can be defined as a type of relationship where first and foremost supervisor and PhD candidate focus on their work: the research to be done, the research design, the progress of analysis, writing and publication strategies. Personal elements are less important, and in extreme cases, regarded as completely irrelevant or taboo for discussion.

Personal behaviour is the opposite: the focus is on personal matters, and in extreme cases work is hardly ever mentioned. The supervisor knows, or tries to know everything about the personal circumstances and characteristics of the PhD candidate, and in meetings personal affairs and emotions get a lot of attention. Often there is or develops a relationship of personal or family friendship, sometimes progressing further than that.

Task behaviour can be very minimal on the part of a supervisor, with hardly any time and energy invested, or it can be very intensive, with daily meetings and lots of joint activities. However, if there is a substantial relationship, it can be of two kinds: a product orientation or a process orientation. In extreme cases of a product orientation, all meetings are always about the results, with a tendency to focus on concept publications or chapters. In extreme cases of a process orientation, meetings are never about results, but always about the process to get to results. In the first case scenario, supervisors generally have schedules of meetings about the discussion of written chapters, and they tend to stick to deadlines. In the second case scenario, supervisors see their role mainly as process managers, stimulating candidates to grow. If candidates are confronted with delays in writing or writing blocks, the first type of supervisor cancels planned meetings, and only wants to meet if there is a written product to be discussed. The second type of supervisor tries to resolve the deadlock, and has intensive meetings to do so. However, sometimes the more extreme types of process managers are very superficial or negligent when there are products (chapters, the thesis as a whole) to be discussed.

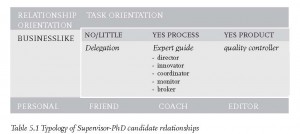

If we look at this typology in a systematic way, six matrix cells can be differentiated, and names can be given to each of the six styles of supervision.

Table 5.1 Typology of Supervisor-PhD candidate relationships

We will briefly sketch the characteristics of each of these six types and focus first on the role of the supervisor. Of course, we should add that a relationship with a PhD candidate also depends on the degree of independence, self-security, expertise, maturity, motivation and commitment, ability to articulate wishes, communication abilities and styles of both the candidate and the supervisor. It also matters if there is only one supervisor or if there are more, and if one of those plays a role of daily supervisor.

5.1.2.1 Delegation (‘leave me alone’): low intensity and businesslike

These supervisors are often deans, heads of departments or leaders of large-scale research programmes. They successfully acquire PhD projects and often are approached to do so because of their prestige in funding circles. However, they do not really have time to be fully engaged in the actual task of supervision and often this is ‘part of the deal’ (although the funding agency might not be aware of it, or be happy about it); ‘delegators’ often tend to ‘manage a research empire’ in which the real work of supervising PhD candidates is left to others to whom the ‘real supervision’ is entrusted. However, on paper they are responsible to the funding agent and, when candidates do their exams or graduate, they have to play a role, and they are also formally responsible for progress and final reports to funding agents. Other words for ‘delegator’ can be: entruster, devolver, transferor of PhD supervision responsibilities.

5.1.2.2 The friend (‘be my buddy’): low intensity but personal

These supervisors never talk about the contents of the research work or it is very rare that they do. Often they know the PhD candidate as a former student with whom a friendly relationship developed or as a family friend or colleague, and they supported the person to start doing a PhD. Meetings are often at home, either with the supervisor or with the candidate or in pleasant places outside work, and beyond an occasional question, ‘How are things going,’ there is little contact about progress or products. But there may be very regular contact about all types of other items. As in all friendships, the supervisor is interested in the person, and if he/she feels that things are going wrong, he/she will try to solve those problems, but indirectly. There is an element of avoiding confrontations, not to jeopardise the friendship. Other words for friend can be: supporter, buddy, confidant.

5.1.2.3 The expert guide (‘tell me what to do’): higher intensity, businesslike and process-oriented

These supervisors keep a distance from their candidates as far as personal elements are concerned. Some don’t know or don’t want to know about the family/household background of their candidates, and never visit them at home. They see their major role as stimulating a process of work improvement and they guide their candidates to grow as scientists. Several types of expertise can be differentiated, and hence this role of expert guide has quite a number of sub-roles:

a) the director: the supervisor who puts a lot of emphasis on directing the candidate in certain theoretical and methodological directions, with a lot of attention on theoretical embeddedness, methodological issues and for the research design; these supervisors will very much stimulate their candidates to consult relevant journals and engage in discussions with many relevant experts in the field; they will stimulate them to go to methods courses, to ‘improve your academic writing’ courses and the like; they will also stimulate the candidate to perform in conferences, workshops and faculty meetings, and there is a lot of attention paid to the preparation of candidates for these performances, focused on argumentation and analysis. If supervisors go to the field for fieldwork supervision, they tend to focus on the quality of data collection and on the chain of argumentation, along with the place the various sources of knowledge gathering occupy; other words for this function are master, authority, specialist;

b) the innovator: the supervisor who stimulates pioneering thinking, at the edge of current scientific thinking and who has a vision of social and scientific change, along with an ability to stimulate creative ideas;

c) the coordinator always puts an emphasis on work schedules, on adhering to deadlines and on process planning; in cases of group supervision or joint research, the coordinator will make sure that the various parties play their roles in an orderly fashion;

d) the monitor always measures progress against work schedules, and is generally very active in making summary notes of meetings and writing the history of the project;

e) the broker will ensure that other parties (in or outside the department; funding agencies) deliver funds and assistance to the candidate and the research project; they will maintain contacts with a wide variety of network partners who might provide useful roles later.

5.1.2.4 The coach (‘steer my ambition’; ‘groom me into academics’): higher intensity, more personal and process-oriented

These supervisors are also very much involved in the growth of a candidate, but not so much as related to their PhD job as such or in so far as the content of their work, but to the growth of their personality. They will put a lot of emphasis on styles of performance in public, scientific fora. They will stimulate candidates to go to presentation training courses and before examination they will suggest mock exams, and they will stimulate candidates to attend many PhD examinations, if these are public affairs (as they are in the Netherlands). They try to understand the personality of the candidate and are aware of their personal circumstances. Whenever there are problems at home or with the (psychological) health of the candidate, the coach will try to be part of finding solutions. The coach is also interested in stimulating the scientific career of candidates beyond their PhD and will actively try to assist them in networking. In the first stages of PhD training, coaches are often involved in facilitation as well: with advice about time management, funding, library, information and other resources, and there is or should be discussion about research ethics and proper research etiquette (and what happens in cases of misconduct, such as plagiarism, financial dishonesty, sexual harassment and theft of intellectual property rights).

5.1.2.5 The quality controller (‘keep me sharp’): higher intensity, businesslike and product-oriented

These supervisors put a lot of emphasis on the written products of their candidates and continuously judge those products on aspects of scientific quality. They only want to meet and discuss after agreed submission of a concept chapter or publication. They will stimulate their candidates always to go for the most prestigious journal and the most influential conference in their fields. Their comments are often of a judgemental kind, without detailed and supportive suggestions for improvements: ‘They have to learn it the hard way.’ They are often extremely cross if candidates do not work according to the agreed schedule, and they are very conscious of timelines and deadlines. If there is an agreed and restricted period for supervision (e.g., the funding agency provides funds for three years), they will generally refuse to continue substantial supervision beyond that period, and they will agree to measures by a department of no longer facilitating candidates (no room, no computer, cancelled institute email address). Other words for quality controller can be: producer, auditor, assessor, grader.

5.1.2.6 The editor (‘help me write’): higher intensity, more personal, product-oriented

This is the type of supervisor who is very product-oriented as well, but who will put substantial amounts of time and energy into correcting mistakes. There is much emphasis on language, both on concepts and on ways of expression, on spelling and on communication in general (‘how to reach your audience’). Candidates always get their work back covered in red marks or – if they have an electronic relationship – full of track changes. Some supervisors would, often after two or three failed attempts to improve the style of reasoning or writing, take over and suggest sentences, paragraphs or even major parts of the thesis. Some will hire the services of professional editors for support. Most editor types of supervisors try to understand the reasons for inadequate (not-yet adequate) quality by trying to know more about the candidate and his/her training. Other words for editor can be: product advisor, scientific language assistant or trainer, corrector, reviser.

5.2 Types of PhD Candidates, Culture and Dynamics

5.2.1 The independent student

Supervisory styles have to do with the personality and position of the supervisor(s), but they also have to do with the personality and position of the PhD candidate. Some candidates have a very independent attitude, and they want to do the job alone. They would prefer a ‘delegator’, without a ‘circus of supervision’ around them, and they want to keep the supervisor at a distance. In extreme cases, they will meet once in the beginning and, the next time, a few years along the line, the candidate presents a full product and graduates on the basis of that product without a single word exchanged in between. These types of candidates do not like being told to go to courses; if they need some, they will organise it all themselves.

5.2.2 Students preferring a personal relationship

Some PhD candidates do not mind a personal relationship with their supervisor, as long as there is not much (or even no) discussion about the progress of the PhD work or its products. ‘You will see it when I am ready.’ If there are problems (e.g., about funds for doing the research or about facilities), they will spread word of it in the circle around the supervisor, and expect their friend to become aware of it and work on a solution.

5.2.3 The businesslike student

There are many PhD candidates who would like to keep the relationship businesslike and who do not like any interference in their personal lives. Businesslike, product/task-oriented personalities like defined roles, clear goals, planned timing, agreed communication patterns and behaviour, and reliability on both sides. They find it irrelevant and sometimes even a bit confrontational for supervisors to know about their home situation. But they like being guided to become a good scientist and prefer a cool, efficient style for meetings that give them useful suggestions about what to do next and how to improve. In some cases, they do not mind, or even like, knowing continuously if they are on the right track, and they prefer supervisors who continuously create an experience of examination in all their meetings. They always try to perform at their best during these meetings and like being judged on the quality of their performance.

5.2.4 The personal-interest, interactive student

On the other hand, there are PhD candidates who abhor those practices and who cannot function without a personal touch and interest in their life and personality as a whole. Personal-relationship, process-task personalities are personality-oriented, empathic, liking social-emotional bonds, with trustful and fluid arrangements. They prefer meetings which start with small talk and they like to share experiences beyond the PhD work. Some prefer getting continuous advice on their performance, with attention to their personality; others prefer focussing on their written work, but they expect a lot of detailed, to-the-point suggestions for improvements. On really difficult parts of the analysis or of the writing process, they would like their supervisors to take co-responsibility, either for doing the job together or for hiring expertise for expert assistance.

5.2.5 Chemistry between student and supervisor

The success of a supervisor-PhD candidate relationship partly depends on what often is vaguely called the ‘chemistry’ between supervisor and PhD candidate. Often there has been some kind of prior contact, for instance, because the PhD candidate was a former student of the supervisor. In cases of previous incompatibility, it is unlikely that people would start the arduous journey of doing a PhD project together. But cases of incompatibility may happen when there are bureaucratic procedures in which candidates are accepted for a PhD project on the basis of their written academic curriculum vitae and supervisors accepted by them without much or any prior contact. Things can go wrong, and that is often quite clear already in the early phases of a project. It is also possible that things may happen between supervisor and PhD candidate which make them change their preferred style. Relationships may become too personal and tensions may develop, which can only really be solved if both supervisor and candidate agree that they should behave in a more businesslike fashion. Particularly when candidates and supervisors spend some time together in the field, far from home, each may encounter characteristics in the other which may jeopardise the relationship, and this may only be solved by agreed to changes in behaviour (or an agreed truce, as long as the PhD project is ongoing), or they split up and the PhD candidate looks for another supervisor.

5.2.6 Departmental culture and the student

What may also influence the relationship is the research (and power) culture in the department, along with institutional changes happening during the process of a PhD project. In cases where departments hire professional assistance with editing scientific work or have in-house training facilities for training in writing academic English, editing roles for a supervisor may become less relevant (and rather expensive to spend their time on). In cases where departments set up a fully institutionalised mentoring and/or coaching system (see elsewhere in this book), the role of mentor and coach may no longer be played by a PhD supervisor. There are departments in which all roles have been more or less formalised in separate functions, with a dean playing the role of delegator, an institutionalised peer group of PhD candidates playing the role of friend, the best specialist in the field of the PhD study (or a group of them) playing the role of expert guide (with psychologists and even lawyers behind them for difficult situations), a research manager playing the role of quality controller, and a professional editor assisting in writing and communication skills. There are cases in which PhD candidates of the same supervisor form informal groups to evaluate and guide their relationship with the supervisor, and sometimes these come to an agreement as to how to avoid certain styles of supervision or how to teach the supervisor to do a better job. In some departments there is an atmosphere of informality, with staff, PhD candidates and students often meeting each other in canteens, coffee shops or even bars, and in which regularly meetings are organised at the homes of the leading professors. Most departments have a regularised arrangement of scientific and departmental meetings in which PhD candidates (or all staff) present their work in progress (‘brown bag’ lunch meetings, five-o’clock get-togethers, Friday afternoon ‘feet on the table’ meetings or similar get-togethers). Other departments do not have those at all, and staff and PhD candidates scarcely meet. The office situation of the department matters as well, of course. If all PhD candidates and all research staff work together in the same building and share the same secretariat and coffee machine, informal contacts will be more regular than if spaces are far apart.

Departments are also part of larger bureaucratic institutions. In the Netherlands a major change took place when the individualised and rather chaotic PhD situation in many departments was streamlined under the umbrella of research schools. But growing bureaucracy also means more emphasis on assessments, and peer reviews of performance and results. In cases where PhD projects are restricted in their time frame (e.g., due to funding arrangements or labour laws), this may be treated more as a guideline than a situation that really has any serious consequences. However, when departments are forced (or force themselves) to become more strict, relationships which started as rather personal and process-oriented, may gradually become more tense and ever more bureaucratic or product-oriented. This can happen particularly when departments only receive new PhD funds if old projects are completed (and theses successfully defended), or when research departments are no longer allowed to give any support/facilities to PhD candidates who are not ready in time; then relationships may really change.

5.2.7 The dynamics in styles of supervision

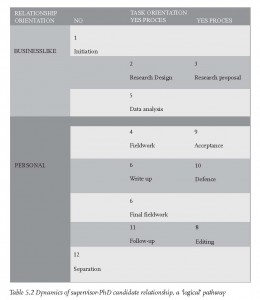

Although each relationship between a supervisor and a PhD candidate is different, and styles of supervision often change in the course of supervision, it is possible to see a certain logic in these changes in styles of supervision during the course of a PhD project. If there is no prior relationship between PhD candidate and supervisor, the initiation of a new project (1) often starts in a businesslike fashion, with no task orientation yet on the part of the supervisor. Often the formal establishment of a link is done in a selection procedure in which supervisors may or may not be involved. When the PhD project has been agreed upon, the next step is a research design (2). During that stage, supervision often is businesslike and directed at the process. It shifts to a businesslike product-oriented relationship when the research proposal has to be presented (3). In some cases this even is a formal exam or a stage that has to be passed formally. After accepting the research proposal, PhD candidates start their actual research data collection, often doing some kind of field work (4). The relationship with their supervisor(s) shifts back to process support and, if the supervisor(s) also visits the fieldwork area, often a more personal style develops (if things don’t go wrong in the field). After the fieldwork phase, the style of supervision often shifts back to a more businesslike approach, guiding the PhD candidate in the appropriate data analysis (5). During the write-up phase (6) and final (wrap-up) fieldwork (7), it becomes more personal again, gradually shifting from a process approach to product supervision, and, in some cases, to intensive editing and lay-out suggestions (8). As one approaches accepting the PhD manuscript (9), the relationship has to become more formal again, culminating in the official defence ceremony (10). Activities after the formal defence (11, e.g., joint publications) often allow for a more personal style again, and the relationship often shifts back from product to a joint process of getting journal articles accepted, or of making policy briefs, local-level popular summaries or jointly organised scientific or policy-oriented conferences and meetings. Gradually the task is completed and, if the process went well, a good personal relationship remains, along with joint pride in the accomplishments (12). The supervisory task now shifts to career advice.

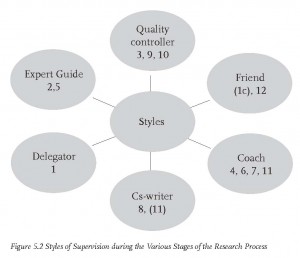

Figure 5.2 Styles of Supervision during the Various Stages of the Research Process

1 Initiation

2 Research design

3 Research proposal

4 Fieldwork

5 Data analysis

6 Write up

7 Final fieldwork

8 Editing

9 Acceptance

10 Defence

11 Follow-up

12 Separation

If we put this logical process of twelve PhD steps in the matrix above, we get the following overview:

Table 5.2 Dynamics of supervisor-PhD candidate relationship, a ‘logical’ pathway

5.3 Some Added Observations from the Literature

5.3 Some Added Observations from the Literature

In one of the well-known books about ‘How to get a PhD’, with ‘a handbook for students and their supervisors’ as a subtitle, Phillips and Pugh have included chapters on ‘How to manage your supervisor’ and ‘How to supervise’; these are full of useful do’s and don’ts, and, indeed as the cover promises, provides a handbook and survival manual for PhD students. It gives a lot of useful advice, but is written in generalities, and without much differentiation.

If we summarise the text that is mainly meant for the PhD candidate, the core messages are that supervisors expect their doctoral students to be independent and to present them with written work that is not just a first draft (hence more a product than a process style of management). Supervisors are said to expect regular meetings with their PhD students and honesty about progress reporting (and if expectations cannot be fulfilled to make them an issue in meetings). If asked for advice, supervisors expect that their advice is followed (but then it should be very clear what that advice is). But by far and foremost, supervisors expect their students to be excited about their work, and they value students who surprise them and who are fun to be with.

Phillips and Pugh talk about the need for PhD candidates to be aware of the management aspects of the relationship and of communication barriers.

‘It is too important to be left to chance.’

They add that during the process PhD candidates tend to know more about the details of a research topic than their supervisors, which can threaten the relationship. It is important in research supervisory teams to be clear about the roles of the first and second supervisors, of daily supervisors and/or mentors (and agreed ways of communicating between these different role players), and there should be agreed rules about change of supervisors, if things really don’t work out well.

What do PhD candidates expect from their supervisors? Quite a lot, if we follow the long list of requirements. It is assumed that all PhD candidates expect to be supervised and that supervisors read their work well. They expect supervisors to be available when needed, and to be friendly, open and supportive. But supervisors should also be role models, constructively critical, with a good knowledge of the research area and a willingness to share their knowledge. It should be made easy to exchange ideas, preferably in a structured weaning programme, coupled with attention for the psychological elements involved. And, finally, many PhD candidates also expect their supervisors to help them get a good job after finishing. Phillips and Pugh again mention the importance of communication, being aware of expectations and evaluating those regularly. For both PhD candidate and supervisor the relationship should be geared to a process of learning, both intellectually and emotionally. There is a special word of warning for cases where a PhD candidate is also part of a larger project or programme for which the supervisor is responsible.

PhD supervision is a separate task from project management and there may be conflicts of interest.

However, the most important action for each supervisor is being a good researcher him- or herself and showing that to the PhD candidates. Joint publication and joint presentations at scientific conferences are important ways of doing that and are often of mutual benefit.

Johann Mouton (2001) differentiates four roles for supervisors, namely, adviser (an element of what we call coach), guide (what we call expert guide), quality control (we call it quality controller as well) and emotional and psychological support (he adds ‘pastoral’ in brackets; we regard it as part of the role of coach, but also in terms of how a ‘friend’ plays such roles). Since a PhD is an apprenticeship degree, this means that supervision is crucial, and success often depends on that relationship. Mouton puts a lot of emphasis on the need for a research contract in which both PhD candidate and supervisor(s) (and their department) agree on important matters. In the Netherlands, most research schools and institutes nowadays use training and supervision plans, which are regularly (e.g., annually) updated, to enable an institutionalised moment in which both PhD candidate and supervisor have to agree on work progress and styles of relationship. According to Mouton the first thing a supervisor can expect from a PhD candidate is that he or she adheres to the research contract and is aware of the requirements and rules therein. The first meeting between supervisor and PhD candidate is a crucial one, and he adds a rather long list of things to discuss and arrange in this first meeting.

Mouton adds five general rules for a healthy and successful relationship: (1) dignity, respect and courtesy, (2) no harassment, (3) accessibility, (4) privacy and (5) honesty. Indeed, the lack of one or more could lead to the failure of the relationship or may become nails in each others’ coffins.

Although specifically written for the South African scholarly market, Mouton does not talk much about one of the often problematic aspects of doing research (and PhD research as well) in a context like the South African one. Erik Hofstee’s book is more explicit about these contextual aspects.

Many PhD candidates, particularly those in the social sciences and in health sciences want their research work to be ‘Research for Development’, and many of their research subjects expect so as well. Many current PhD candidates themselves have experienced the harsh conditions of poverty, inequality, lack of access to basic facilities and human rights abuses during the time of apartheid, with some of these also continuing up until this day. Many of them have gone through very difficult primary and secondary school experiences, with South African schools having been in the forefront of the struggle for a democratic South Africa. There are many written accounts of what pupils experienced during those years, but one analysis of the struggle over education in the Northern Transvaal can be regarded as a nice joint product of South African and Dutch collaboration. Many current PhD candidates have played roles as activists, and often this was one of the motivations to do a PhD-level study which would also benefit the people who are being studied. The emphasis on action research, development-oriented research, and politically motivated research may clash with more ‘ivory tower’ attitudes among some (though certainly not all) South African supervisors. And the other way around: some supervisors do expect all their PhD candidates to be motivated by developmental urgency, and some PhD candidates may have and would like to see a bit more of a distant attitude. Everywhere in the world academics are confronted with major changes in the knowledge society in which non-traditional agencies become leaders in scientific discoveries and practices, sometimes with very few connections with the academic community (except for trying to get their best alumni). On the one hand, these are trans-national corporations and other business companies with knowledge-intensive activities; on the other hand, many organisations in civil society have become knowledge-intensive and often pioneering agencies. For many PhD candidates their engagement with these new centres of knowledge will be different from that of their supervisors, and that also includes major differences in communication styles and information etiquette, with much more emphasis on electronic resources and fast, fluid ways of information exchange. Methodology textbooks are now also written by individuals based in those new centres of innovation. It would be wise to include discussions coming from those circles, in regular discussions between PhD candidates and their supervisors.

There are many ‘how to’ texts available, however, not all are useful or empowering. In a recent critical review, Barbara Kamler and Pat Thomson criticized the genre for often being very paternalistic and continuing the power structures existing at many universities all over the world. Reflecting on the type of relationship in the various stages of the PhD project and about the social psychology and educational philosophies behind these relationships may be a useful way to challenge the existing situation.

5.4 Conclusions

It is important for both chief supervisors, daily supervisors and/or mentors and PhD candidates to reflect on the desired and actual styles of supervision once in a while, on how these fit the personalities of the supervisor/mentor and of the candidate, and also on how they reflect the type of research, the stage in the research and the departmental, university/research school and even the social context in which PhD projects take place (with ‘social’ also meaning economic and cultural). It would be good to do more empirical tests about styles of supervision, using examples such as those of Khan and Lakay (2005: 45). Adapted from our typology, this empirical test uses the following questions. It can work with different scales; we have selected the Likert scale to be the most suitable here.

The basic question is: ‘How important a contributor did/do you find each of the following supervisory roles to be in assisting you towards completing your thesis?’

– Delegation

– Friendship

– Expert guidance (if wanted, with further detail: director, innovator, coordinator, broker or monitor)

– Coaching

– Quality control

-Co-writing (or editing)

The test can be taken after a project has ended (with or without a thesis product, an ex post approach) and it can be taken during or even before a project starts (as an ex ante discovery of desired relationships), and with more or less sophistication.

Using the same approach, more specific questions are: ‘How important were (or would you like to be) the supervision styles in the various stages of the PhD process’, differentiating between:

1= Initiation,

2= Research design,

3= Research proposal,

4= Fieldwork,

5= Data analysis,

6= Write up,

7= Final fieldwork,

8= Editing,

9= Acceptance,

10= Defence,

11= Follow-up,

12= Separation,

or any other stages that are relevant in the particular PhD project.

For ex post evaluations PhD candidates can also be asked to add a judgmental question: ‘How good or successful was each of your supervisors in playing the various roles (in the various stages of the PhD process)?’ – again using a five-point scale:

1= very bad/unsuccessful,

2= not successful,

3= moderately successful,

4= good/successful,

5= excellent.

These kinds of exercises could inform and refine improvements towards effective PhD supervision in the future in the Netherlands, South Africa and elsewhere.

—

Next Chapter – Chapter Six: http://www.rozenbergquarterly.com/?p=1945