Effective PhD Supervision – Chapter Six – A Holistic Approach to PhD Support

SUPERVISION, COACHING and MENTORING

SUPERVISION, COACHING and MENTORING

6.1 Mentoring and Coaching: Complementary Resources

‘Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?’

‘That depends a good deal on where you want to get to,’ said the Cat.

‘I don’t much care where –’ said Alice.

‘Then it doesn’t matter which way you go,’ said the Cat.

6.2 Comparing Supervision, Coaching and Mentoring in Practice

6.2.1 Gaining competence

Supervision of a PhD candidate has been described in terms of models, personality, formal institutional structures and contract agreements. Supervision is often learnt through experience: one’s own – from having been supervised, from external examination of theses, from serving on post-graduate committees, from participating in PhD student-presentation sessions, from sitting in on a PhD student’s advisory committee, from serving on post-graduate committees, from co-supervision with a more experienced academic and from supervising different students. Supervision skills are also developed from workshops on supervision and through reading ‘how-to’ books or research into PhD work. A supervisor also draws on a certain amount of pedagogic content knowledge as well as, of course, discipline content knowledge.

Coaching, we have tried to show, is a less common process as it involves specific training in skills that are not picked up through experience alone. Coaching is, however, consonant with current research into pedagogy in that it is strongly student-centred, holistic and trans-disciplinary. Coaching also promotes independence, reflection and self-directed action – all of which are essential for an emerging researcher. Coaching is usually short-term, formal and goal-oriented, and may involve two people from completely different fields or disciplines. Coaching skills need to be taught and then practiced.

Mentoring, we have claimed, is often long-term, informal and field- and personality-based. While a coaching relationship could be one of equal power, mentoring typically involves an older, more experienced mentor and a student. A good mentor has often himself been mentored well, and therefore understands both the value and process of passing on a lifetime of experience, sharing connections and possibly ‘grooming a successor’.

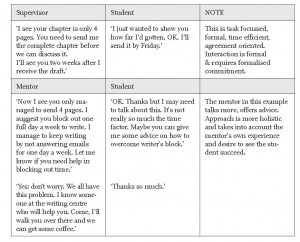

6.3 Dialogues from Different Perspectives

In these dialogues we will show differences in the interactions between a student and a supervisor, and a mentor and a coach.

6.4 Integration

While there are many advantages to having a supervisor, separate mentor and a professional coach (for a set period), these roles can be integrated. It may seem logical that supervision, mentoring and coaching relationships are mutually exclusive, and that the approaches, assumptions and skills in supervision, mentoring and coaching are contradictory. However, without being thoroughly schizophrenic, a PhD supervisor could manage to include the three roles interchangeably, drawing on skills from all roles. In this case it is wise to sometimes advise the student: ‘Now I will leave the coaching approach and tell you what I would do in this situation.’ This situation is illustrated through dialogues between supervisor/coach/mentor/student below.

6.5 Epilogue

Writing a PhD thesis is not a linear process; there is no ‘one size fits all’. Pellucid pathways and preset templates may add to systemic efficiency but offer little in terms of intellectual exploration. Doctoral students should be questioning prevalent discourses, contributing controversial – or at least fresh ideas – and not simply complying with throughput requirements. So, of course, self-help/how-to books have their limitations. We have tried here to broaden the opportunities for finding one’s own path creatively and reflectively, not for learning the ‘rules of the game’ but for questioning the ‘game’ and for becoming more of a person through the process and through connecting with others along the way.

We must also draw on our cultural resources, ensuring awareness of worldviews, and not be overly drawn in to dominant paradigms in the traditional supervision process. The more flexible model suggested here will provide a more nuanced relationship that will draw on the strengths of both individuals and the unique context in which this holistic approach is viewed.

—

Next Chapter – Chapter Seven – http://www.rozenbergquarterly.com/?p=1963