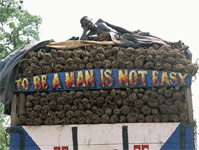

To Be A Man Is Not Easy ~ I Saw Dead People Covered In Dust. Interview With Mr. Darko

I am Mr. Darko, 37 years old and I am married with two children. I’m from here in Nkoranza and I work as a car electrical mechanic in town. I will tell you about the experiences I had on my way to Libya. About three years ago I went to Libya. I started from Ghana, passed Burkina Faso and went on to Niger and then straight into Libya. That’s what I thought, but it happened otherwise.

I am Mr. Darko, 37 years old and I am married with two children. I’m from here in Nkoranza and I work as a car electrical mechanic in town. I will tell you about the experiences I had on my way to Libya. About three years ago I went to Libya. I started from Ghana, passed Burkina Faso and went on to Niger and then straight into Libya. That’s what I thought, but it happened otherwise.

From here to Burkina the road is acceptable but once in Niger the going is rough. From Burkina you get to Niamey which is the capital of Niger. There are many Ghanaians there waiting for their chance to get transport into Libya. In Niamey you wait until about thirty people have assembled, then you all get into an Urvan minibus. These buses take you to Agadez. Ghanaians wait for each other till they have the money to hire the car together. We Ghanaians, we like to travel together.

“Everyone pays about 300,000 cedis which is 30 dollars to the driver. The driver is not from Ghana, he is from Niger. You take off and although the distance is not too long the road is so bad that it takes you three to four days to get to Agadez. This town is the second capital of Niger and lays at the edge of the desert. The military police stops you many times and each time you have to pay up. When they see Ghanaians in the bus they say: ‘stop, out, pay.’ If you don’t pay they will throw you out of the car. You waste a lot of money on that stretch alone. Every time they stop you, you pay 5 dollars, this is on top of the 30 dollars which you already had to pay to hire the car. Every time the police halts the car they take our passports and documents and we don’t get them back till after paying the bribe.

So after three days and much money you get to Agadez. After Agadez it is all desert, there is no more road. There is a trail which the drivers know but they miss it sometimes when there is a desert storm.

Whenever we stop we sleep beside the car. Really to be honest you cannot sleep. We don’t feel sleepy for while you sleep anything can happen. People will grab your food and your money if you are not alert. So it is not sensible to sleep, so we don’t sleep. It is also very cold the more you get into the desert so you could not even sleep if you wanted to.

There are Toyota land-cruisers and heavy trucks in Agadez; these are the only cars that can drive through the desert. With 30 other people I got into a Toyota Land-cruiser to start the journey through the desert. If you are less lucky you get into a large truck which takes two hundred people at the time! You stand like sardines in these large trucks and the sun burns you and the desert wind fills your eyes and your mouth and even inside your ears with sand. Whatever type of car it is, it is overloaded and still, some people force themselves to get inside by sitting on the edges or by just jumping and clinging to the car.

Once in the desert

Once in the desert everybody is allowed a 7 gallons container with water to drink, and some small gari to eat, nothing else. The water-containers are tied to the car and hang outside, side by side. Everybody strictly keeps to his own water else there is murder. This water has to last you. When there is a stop you take your tin cup and put some gari in it and then add water and then you eat. Everybody loses weight but we Ghanaians are strong and we don’t care. In fact we can do anything, anything at all.

From Agadez to Libya it is ‘live or die’. Everybody becomes serious and has to struggle for himself. There are middle-men in Agadez who organize a car for you. You have to pay them to get into a car. Everybody likes to earn money from us and we have no choice but to pay. So you board your overloaded car! There is not any shade on the way and there is no road, some cars miss the signs and get lost, in which case you die.

But we went in a line, a caravan of five cars from Agadez to Durku, which is near to the border of Libya. That trip is a four day journey through the sand. When the driver gets tired he makes a stop. Then everybody sleeps in the dust but no-one actually sleeps. Early morning the driver shouts ‘hajaaa’, ‘hajaaa’, which means up, up, and you go again. You take some of your water from your container and mix it with your gari and that is your breakfast. Every time there is a stop the same you eat and rest a bit and go again.

Some start walking

When your car breaks down there is trouble. A breakdown is painful and then everybody fights for himself to live. You have to get on another car. Some start walking but the dust covers everything and you may panic and then you easily get lost with that sand everywhere.

My car did not break down but another car gave up and we saw people in the desert from that car. We took seven extra people aboard from out of the sand who otherwise would have died. No one knew how they still could fit into our car but they did, they joined our car. The other cars also took as many people as they could. If you did not make it to a car you died.

I saw dead people there, and what they do is cover them with some dust and put their passport on top of the heap. This is because someone might pass who knows them and if they do they take the passport and show it to the relatives.

Stranded in Durku

When we arrived in Durku we thought we had made it but then the big problem started! It was in December, three years ago. The trip had taken more than two weeks in all, and we were close to Libya. But then in Durku we got stranded.

There is only one type of car that can bring you from there to Libya. The land-cruisers in the meantime had returned already. When I came to Durku it was just at the time that Al-Qathafi had made a decree that nobody should enter Libya through the desert borders anymore! We were all locked up in Durku, what could we do? We waited because the president could change his mind which he often does. But no, he never lifted the ban and we were stuck in Durku, which is the farthest village in the desert of Niger.

The food was running out. Only water in abundance because of a natural source, but there was no food to buy except very expensive bread.

With me there were more than 500 Ghanaians stranded and many others like Nigerians and those from Mali and Niger. The Ghanaians stayed together, waiting.

Every day more people assembled in that tiny village. The land-cruisers brought loads of thirty to forty people and the heavy trucks brought them by the two hundreds. It was a complete refugee camp and nobody wanted to turn around and go back to Ghana. We ate what we had and we bought when we had the money but there was little money on me.

I kept all my money safely on my body and counted it every day. Some people had not enough to return with. Some were too adventurous and tried anyway to force themselves with that one car into Libya. We all waited but they did not succeed. After a number of days the car came back with only a few people left, very few people left. Most had died from thirst. The driver said that heavy border guards were patrolling at the border of Libya and there was no way through.

Waiting

All this happened because some Nigerians and Malians has smuggled cocaine and drugs into Libya through the desert. The president got to know of it and closed the borders just when I had arrived for my passage to Libya. It was a very hard blow to my plans.

You count your money every day and the day you find you have just enough to return then you have to return. We stayed three weeks waiting. We were quiet because of those who had died trying their luck crossing over to Libya.

I decided to return, I had enough money for myself and I could pay for a young boy from Nkoranza. I looked after him and took him back with me.

A few women were there too but mostly all this is too hard for women. Women also cannot push a car when it gets stuck so the drivers don’t want them.

I left Ghana in December and I returned with the young boy in February. I was forty days on the road and three weeks in that border town, waiting.

I could not call or send a message but the word went to Ghana that we were all coming back. My family and my wife and children were so happy to see me alive. They had all heard about the news that many people had died. So they rejoiced but all the same my wife was sad that I had failed to get into Libya.

Your home town

If you help a friend who has no money you have to take a friend from your own town. That is the only way by which you will get your money back. If you see someone stranded from another town like Nkawkaw you don’t help him for you never find your money back again. Those who have no helper will die, they just roam around till they drop down in the sand. There in that place we all have to fight for ourselves alone.

The boy from Nkoranza was lucky that he met someone like me who helped him. He is from my town. The boy paid back and he became a friend. His family is very grateful.

My wife was happy but sad. Happy for life but sad for the wasted money which we had lost. We wasted three million Cedis then, that would be five million now because of inflation. That is 500 dollar. We still cry about the waste. When I have the money now I will go again and this time I will succeed. I want to go for here in Ghana there is simply no future for me and my family.

Once in Libya you can either earn enough to start your own business here in Ghana or, if you are lucky, you get into Spain and then you get more money for you take any job you can. My brother is in Spain for over four years. He often calls me and tells me how to go about getting out of Ghana. He was the one who gave me money to travel to Libya when I failed and had to return. Right now last week he called me again and said ‘Come! Try again!’ Yes I am soon going to try again!

—–

Interview with Mr. Darko from Nkoranza (Ghana) – October 2005

Ineke Bosman – To be a man is not easy – Stories from Ghanaian emigrants

Rozenberg Publishers 2007 – ISBN 978 90 5170 850 9

From the Preface

It all started with Kwame Baffoe, the guy who ‘only wept once’.

Kwame was the hospital driver at the time that I worked in Nkoranza Hospital as tropical doctor. One day Baffoe disappeared. After two weeks his relatives came to ask for his end of service benefit. I was then the medical director as well as the administrator and I had to say ‘no, he vacated his post. Sorry no entitlements when someone walks out and does not return within ten days. Trade Union agreement. But where is Baffoe?’ They smiled silently and left. This was in the mid-eighties.

I returned to Nkoranza after studies in Chicago and, apart from caring for my mentally handicapped children, I had received the appointment from the Ministry of Health to be regional mental health director in our regional capital, Sunyani. This meant a lot of travel up and down. I bought a car and then …I saw Baffoe! It might have been 1997. He was operating his minibus as a taxi and looked well, the same half-smile plus now a tiny little belly. I asked him ’Can you help me? Drive me to Sunyani any time I need to? Which is often?’ ‘Yes’, he said. Baffoe is not a man of many words.

That’s how we met again and, many words or not, one day he told me his story. How and where he traveled and how and when he returned to his country Ghana. I was impressed, flabbergasted is the more appropriate term maybe, especially since he told me the story the way you talk about a shopping trip at the supermarket. Facts, not emotions.

I felt the topic of his ‘end of service benefit’ still hanging in the air. And yes a few days later he asked me why I withheld ‘his money’ when he left for Libya. I told him that I did what I thought was right and that it was not ‘his money’ but ‘the hospital’s money’. ‘Okay’, he said. ‘Now, older, and after understanding all that you went through, I might have been milder’, I said, which is true. ‘No, you are right. Okay’. Speaking about it after so many years settled the issue sothe case was closed.

In my dreams his hazardous travel stories kept following me and one day last year, when I had some more leisure time, I decided to interview him once again and to document his experiences. He agreed readily. So did thirteen other persons here in Nkoranza. It became a passion, almost an addiction, to hear these stories and write them down metaculously. All these interviewee’s became my friends and we keep meeting in town. I could have done hundreds more of these interviews but to everything there is a natural end.

See also: http://www.operationhandinhand.nl/

The former Dutch tropical doctor Ineke Bosman once had a very special dream: the creation of a safe and loving place to live for intellectually (and often multiple) disabled children in Ghana. These children are still undervalued and abandoned, among others as a result of the widely spread fear for “evil spirits”.

By founding the Hand in Hand Community in Nkoranza in 1992, Ineke Bosman was able to make her dream a visible and unique reality. Ineke retired in 2009 and left for Holland. Since then Albert van Galen, together with his wife Jeannette, has taken over the leadership of this wonderful community.