IIDE Proceedings 2011 ~ Exploring Dooyeweerd’s Aspects For Understanding Perceived Usefulness Of Information Systems

Abstract

Abstract

The degree to which people believe using a system will enhance their job performance: this is the definition of Perceived Usefulness (PU), one of the main constructs in Davis’ Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). TAM was specifically meant to explain computer usage behaviour and to predict individual adoption and use of new IT to answer the question of why people do not make more use of IT. Over the past two decades many studies reiterated the importance of PU by adding various constructs to it. However PU is regarded as a ‘Black Box’ that needs to be opened. Barki (2008) draws our attention to the importance of constructs and approximately 70 constructs related to PU have been collected by Yousafzai et al. (2007). However Barki argues for the reconceptualization of constructs. First we need to know what is important in each construct. Dooyeweerd’s philosophy of everyday life assists, by his suite of aspects, to find the meaning of each construct and to show a way of reconceptualizing constructs that overcomes seven problems with Yousafzai et al.’s set. This employs a new approach, which is expected to lead to a more penetrating understanding of IS usefulness.

Keywords:

Technology Acceptance Model, Perceived Usefulness, Dooyeweerd, Aspects, Construct reconceptualization.

1. Background

Fred Davis’ (1986) Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) was introduced and developed under contract with IBM Canada, Ltd. where it was used to evaluate the potential market for a variety of then emerging PC-based applications in the area of multi-media, image processing, and pen-based computing in order to guide investments in new product development (Davis and Venkatesh, 1995). TAM was specifically meant to explain computer usage behaviour and to predict individual adoption and use of new ITs (Davis, 1989) . It posits that individuals’ Behavioural Intention (BI) to use an IT is determined by two beliefs: perceived usefulness (PU), defined as “The degree to which an individual believes that using a particular system would enhance his or her job performance” (Davis, 1989), and Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU), defined as “The degree to which an individual believes that using a particular system would be free of physical and mental effort” (Davis, 1989). It further theorizes that the effect of external variables (antecedents or constructs), such as Design characteristics, on Behavioural Intention will be mediated by PU and PEOU. According to Davis, one of the key purposes of the TAM was to provide a basis for tracing the impact of external factors on internal beliefs, and this has implied that without a better understanding of the antecedents of PU and PEOU practitioners are unable to know which levers to pull in order to affect these beliefs and, through them, the use of technology.

1.1 Constructs in models of IS use

Over the last two decades, there has been substantial empirical support in favour of TAM (Lee et al, 2003) by adding various external variables to the salient beliefs and modifying the original model in different ways. However, TAM has recently been criticized severely by Benbasat and Barki (2007) stating that:

“The intense focus on TAM has led to several dysfunctional outcomes … TAM-based research has paid much attention to the antecedents of its belief constructs and diverted researchers’ main focus from Investigating and understanding both design and implementation-based antecedents … Many studies have reiterated the importance of PU with little attention to investigate what actually makes a system useful … That is to say PU and PEOU have been treated as “Black Boxes” and few have tried to open them … Also the effort to “patch up” TAM in evolving IT context have not been based on solid and commonly accepted foundation, resulting in a state of theoretical confusion and chaos.”

Over the years, constructs like Trust, Image, Self efficacy, Results Demonstrability, Implementation Gap, System Quality, Computer Anxiety and Perceived Enjoyment, have been regarded as the additions that have been made to TAM. Benbasat and Barki (2007) state that:

“It is clear from extensive work on TAM that usefulness is an influential belief; therefore, it would be fruitful to investigate the antecedents of usefulness in order to provide a design oriented advice. However, to be able to do so in a systematic fashion, we first have to develop taxonomy, or preferably a theory, of usefulness.”

This paper suggests a way of investigating the antecedents of usefulness.

Towards this end, Barki (2008), points to the importance of well-conceptualized constructs that their contribution to the advancement of knowledge is evident. However, most literature mainly focuses on ensuring and testing the validity of constructs and few guidelines are available for identifying interesting constructs and how to go about conceptualizing them. Too little attention is given to the early stages of construct development, during which they are conceptualized. Therefore Barki calls for attention to be given to clarifying the definition of constructs, specifying dimensions and their relationships, applying them into different context and expanding the concepts underlying them.

In this paper we aim to go through conceptualizing constructs that relate to PU, in hope of opening the “Black Box” of usefulness. Specifically, we make use of Yousafzai’s (2007) 70 collected constructs, to argue the need for a new approach. Following Barki’s (2008) proposal to reconceptualize constructs, an argument is made that Dooyeweerd’s notion of aspects may provide a fruitful approach. These aspects are then applied to a selection of Yousafzai’s constructs, to investigate their deeper meaning. At the end we discuss the results and provide pointers for future research. The readership of this paper is two groups: researchers and practioners interested in conceptualizing constructs and scholars interested in application of the fifteen aspects of Dooyeweerd.

1.2 Collected constructs of perceived usefulness

After years in which ease of use and user interface had been the major interest of the human computer interaction community, Davis’ (1989) Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) introduced clarity to the intuition that usefulness is fundamentally distinct from ease of use and cannot be reduced to it. As such seminal papers do, it received thousands of citations and spawned a sizeable research into finding such external variables. TAM and its variants have been validated many times by positivist research methods, each time introducing new external variables that determine Perceived Usefulness and/or Perceived Ease of Use.

Taking previous studies into account, Yousafzai et al. (2007) conducted a meta-analysis of the TAM based research, arguing that over the past two decades few studies have attempted to validate the full TAM model with all of its original constructs. From different researchers in different studies and contexts, they collected together many of the external variables, finding 70, most of which were antecedent to PU. To bring a little order to the complexity that 70 variables exhibit, they are categorized into three main groups, and a sizeable ‘Other’ group:

Organisational characteristics:

Competitive Environment, End-User Support, Groups’ Innovativeness Norm, Implementation Gap, Internal Computing Support, Internal Computing Training, Job Insecurity, Management Support, Organisational Policies, Organisational Structure, Organisational Support, Organisational Usage, Peer Influence, Peer Usage, Training, Transitional Support

System characteristics:

Accessibility, Access Cost, Compatibility, Confirmation Mechanism, Convenience, Image, Information Quality, Media Style, Navigation, Objective Usability, Output Quality, Perceived Attractiveness , Perceived Complexity, Perceived Importance, Perceived Software Correctness, Perceived Risk, Relevance With Job, Reliability and Accuracy, Response Time, Result Demonstrability, Screen Design, Social Presence, System Quality, Terminology, Trialability, Visibility, Web Security

User personal characteristics:

Age, Awareness, Cognitive Absorption, Computer Anxiety, Computer Attitude, Computer Literacy, Educational Level, Experience, Gender, Intrinsic Motivation, Situational Involvement, Personality, Perceived Developer’s Responsiveness, Perceived Enjoyment, Perceived Playfulness, Perceived Resources, Personal Innovativeness, Role With Technology, Self-Efficacy, Shopping Orientation, Skills and Knowledge, Trust, Tenure in Work Force, Voluntariness.

Other variables:

Argument for change, Cultural Affinity, External Computing Support, External Computing Training, Facilitating Conditions, Subjective Norms, Situational Normality, Social Influence, Social Pressure, Task Technology Fit, Task Characteristics, Vendor’s Co-operation

(Note: Navigation, Objective Usability, Perceived Playfulness and Cultural Affinity are external variables that have been added only to PEOU which is not the focus of this study.)

An opportunity is provided by their study to gain a broad and perhaps deep picture of usefulness. This study begins to critically analyse them. But in order to do this it is necessary to find a sound basis on which to make such critique.

2. Need for a new approach

We could, in principle, use all these 70 constructs as criteria by which to understand, judge and evaluate the usefulness of an IS. As soon as we try to do so, however, we find a number of problems.

The first and most obvious is that this set is completely unmanageable, even when categorized into four groups as Yousafzai does. We need an approach by which to manage complexity.

Secondly, even so, the list of constructs is not likely to be complete. Computer Attitude is included, but other attitudes are not mentioned. Religious belief can also play a part, such as with the Amish sect in America, who resist modern technology, but is not included. User Participation (Barki 2008) is also missing from the above list. We need an approach that encourages the discovery of missing constructs.

Thirdly, some constructs are over-specific to a particular author’s interest or a particular type of use, such as ‘Shopping Orientation’. We need an approach that discourages over-specific constructs.

On the other hand, other constructs are ambiguous, such as ‘Terminology’ and ‘Facilitating Condition’. Barki (2008) argues that ‘User Participation’ is interpreted in several ways as either behaviour or attitude, so that results from different studies contradict each other. We need an approach that cuts through ambiguity.

Fifthly, there are overlaps between some of these constructs. For example, the Facilitating Condition overlaps with Perceived Behavioural Control in the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB), and Social Influence overlaps with Subject Norm in Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) that is the Origin theory of TAM. We need an approach that, of its nature, tends to avoid overlaps.

Sixthly, it may be questioned whether Yousafzai’s three categories (Organization, System, Person plus ‘Other’) is the most useful or appropriate categorization. Other categorizations are offered, such as near-term usefulness and long-term consequences (Chau 1996b), intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation and learning goal orientation (Saade 2007), and hedonic versus instrumental use (Van der Heijden 2004). This raises the question: on what basis is it useful to categorize the constructs, in order to manage the complexity thrust upon us by 70+ constructs? We do not want to arbitrarily select one categorization among many, and to employ all of them brings its own complexity. We thus need an approach by which construct categorization can be grounded on something more fundamental.

Finally, the majority of people exposed to these variables were students and sometimes knowledge workers in laboratory studies. Most studies were undertaken in the USA. It is not clear how well the constructs translate into other cultures and usage contexts. Gefen et al. (2003) suggest that TAM is not just for work-related activity, but also applicable to diverse non-organizational settings, and they redefine PU as “a measure of the individual’s subjective assessment of the utility offered by the new IT in a specific task-related context”. We need an approach that is applicable across many contexts.

In his article ‘Thar’s Gold in Them Thar Constructs’, Barki (2008) conveys the message that although there is much potential in the constructs, they need reconceptualization. This must occur before attempting to address the problems above. While by introducing new constructs researchers can contribute to research and practice in the IS field, they can also make an equally strong contribution by better conceptualizing existing constructs. He describes four parts to an approach to construct conceptualization:

Providing a clear definition. There are concepts that are often mentioned by researchers, which are either poorly specified or sometimes even undefined. These are candidates to become constructs as long as they are defined clearly and “deliberately and consciously invented or adopted for a special scientific purpose” (Kerlinger & lee 2000).

Specifying a construct’s dimensions and their relationship. Many constructs are multidimensional. For example, conflict can arise from disagreement, interference or negative emotion or a combination of these (Barki & Hartwick 2004). In order to reconceptualize constructs we need to identify the dimensions in each and determine the conditions under which all or only some are needed.

Exploring how a construct applies to alternative contexts. The third approach is to reflect how a given construct can apply in different contexts, such as technological, organisational or individual. For example, might each construct be valid in hedonic contexts as much as instrumental ones (Van der Heijden 2004)?

Expanding the conceptualization of a construct. Barki suggests that, instead of seeing constructs in terms of attributes and functions, they could be seen as constituted in human behaviours, which are diverse in kind. For example, system use is better seen as an amalgam of human behaviours: “the more a person engages in [Barki gives a list of behaviours here] the more the person is viewed to be making ‘use’ of the system” (p.15). System use, when seen in the traditional manner, is very narrow, but when seen as a set of behaviours, as a second-order formative construct, it becomes richer, and “rich measures are currently lacking in the IS literature.”

If we are to follow Barki’s advice, we need an approach that enables us to identify distinctly what is important in each construct, especially where this is multidimensional, which does not presuppose a certain context, and which can view constructs as constituted in a coherence of diverse human behaviours. One approach that facilitates all these is that based on modal aspects of the Dutch philosopher Herman Dooyeweerd.

3. Dooyeweerd’s philosophy

IS usage includes humans and IT, and so requires philosophy that acknowledges the possibility of genuine point of contact between technology and human beings. Being mostly of the life world, with the human being in the social context, usage requires a philosophy that affords dignity to everyday life and to what it means to be fully and socially human. Thus materialist and rationalist philosophies are unlikely to be helpful (Eriksson, 2001). To deal with the constructs of PU that are mostly of human origin but cross cultures, a philosophy is required to transcend and yet uphold the perspective of human stakeholders.

The importance of philosophy in this area is more highlighted by Basden (2001), who differentiated between benefits and detriments of employing IT in human application tasks based on the philosophy of everyday life introduced by Herman Dooyeweerd (1894-1977) who was a Dutch lawyer and philosopher. His philosophy was a reaction against the the Neo-Kantian trend in continental thought prevalent at that time. The result of his work may be organized into five distinct yet interrelated, domains of thought: the theory of religious ground motives, the modal theory, the theory of time, the entity theory or theory of individual structures, and the social theory (Eriksson, 2001). For the purpose of this study we found the modal theory worthwhile in meeting the research objectives.

3.1 Modal theory

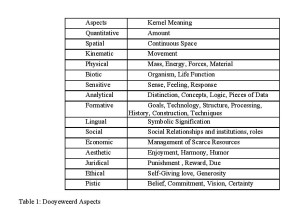

The Modal Theory emerged from Dooyeweerd’s comprehensive studies of theoretical thought and its relation to human reality. Dooyeweerd maintained that our thought is based upon and bound to our experience and that this experience exhibited a number of distinct modalities (or levels, or aspects, or dimensions, or spheres) of organization or laws. Accordingly a modality emerges out of human interaction with reality which includes both perceptions and conceptions (Eriksson, 2001), and it is a particular type of knowledge that has its own unique and distinct characteristics. Dooyeweerd proposed 15 modalities (aspects of everyday life) which are listed below in Table 1 (the left column is aspects and the right column shows their kernel meaning):

Early aspects anticipate the later aspects (for example, the lingual anticipates the social) and later aspects give more meaning to earlier ones. Each aspect is a sphere of meaning that is centered on a kernel meaning. Dooyeweerd believed that kernel meaning of aspects cannot be defined by theoretical thought, but can be grasped by intuition. The aspects cannot be directly observed, but they are expressed in things, events, situations, and so on as ways these can be meaningful. All human behavior involves functionality in a variety of aspects, usually all the aspects. By this we do not mean that aspects are different parts of human behavior, but rather that they are different ways in which it occurs meaningfully. To Dooyeweerd “each aspect plays different but necessary part in making life richly good” (Basden, 2008). Therefore, all things within our experience make sense by reference to one or more of the aspects.

IS usage is everyday human experience with the system and so can be thought about in terms of aspects. Basden (2008) suggests that any software might be used for a wide range of purposes, each meaningful in various aspects. To give an example, although we might play a computer game for fun (aesthetic aspect), we might sometimes play it as a social activity (social aspect), sometimes to boost our image of ourselves (pistic), and so on. Basden (2008) introduces the concept of Human Living with Computer (HLC) as “what the users experience when employing the computer in everyday living. Aspects of living that might somehow be affected by, or affect, the use of the computer beneficially or detrimentally”, and to explain the structure of HLC we are concerned with how human being function in the aspects that are their everyday living.

Basden maintains that Davis (1986) consideration of HLC is narrow because its concern is restricted mainly to the formative and perhaps economic aspects of IS use. Widening the concern to all aspects is likely to enrich it. So the present study uses modal theory as a tool for finding and understanding the everyday life meaning of each construct added to PU.

3.2 Why Dooyeweerd modal theory is likely to be fruitful

Each construct has been suggested and devised because it is meaningful to its author. Since aspects are spheres of meaning, the meaningfulness of each construct may be explained in terms of one or more aspects. So we employ Dooyeweerd’s suite of aspects for reconceptualizing the constructs and tackling the various problems of Yousafzai’s list. Dooyeweerd’s suite can uniquely assist in conceptualizing constructs in the way Barki (2008) calls for, for the following reasons.

To provide a clear definition of a construct requires clear delineation of distinct types of meaning on which the definition can be founded. Discourse analysis can expose meanings but its clarity of delineation depends on the analyst being both highly skilled and devoid of bias so that one type of meaning is not mistaken for another. The former requirement would restrict construct definition to elite experts, while the possibility of the latter is thrown into question by thinkers as wide-ranging as Polanyi (1962), Habermas (1972), Foucault (1972) and Dooyeweerd (1955). By contrast, Dooyeweerd’s suite of aspects already provides a good delineation of meaning-types at a foundational level and, since each kernel meaning can be grasped by intuition, meaning-delineation is no longer restricted to experts. Moreover, Dooyeweerd presupposes bias in all human thinkers but aspects of his kind transcend it.

To investigate multiple dimensions of a construct in a systematic way depends on committing oneself to a pluralistic ontology. Those offered by Hartmann (1952) and Bunge (1979) do not easily allow for simultaneous multiple dimensions. Dooyeweerd’s aspects, by contrast, are present simultaneously in all things, so can be treated as dimensions, and their mutual irreducibility ensures that the dimensions are othogonal to each other.

To consider constructs across different contexts requires a basis for understanding differences in context. Dooyeweerd’s aspects provide this for contexts that are roles or reasons for using the IS. Instrumental use of an IS is dominated by the economic and formative aspects, while hedonic use is dominated by the aesthetic aspect of enjoyment and the psychic aspect of feeling; thus Dooyeweerd’s suite accommodates both of the uses highlighted by Van der Heijden (2004). However, Dooyeweerd’s aspects can go beyond this because there are yet other aspects, pointing to contexts of, for example, social use, lingual use, juridical use and so on. This avoids having to squeeze the diverse variety of use into only two contexts.

To consider widening the way constructs are conceptualized, from attribute-function concepts to something constituted in diverse human behaviours, requires a shift from a static substance-oriented philosophical foundation, such as emanated from ancient Greek thought, to something more dynamic. One contender is process philosophy (Whitehead) but this does not so easily allow for diversity. Dooyeweerd’s philosophy, like process philosophy, sees things as constituted in, and arising from, functioning, but has the advantage that the types of functioning that it recognises, which are aligned with the aspects, are diverse and distinct and yet inter-dependent. For these reasons, we will employ Dooyeweerd’s aspects in conceptualizing the constructs.

4. Research methodology

The research of which this study is part adopts an interpretivist rather than positivist approach, because its aim to not to test a theory but to gain understanding and insight: insight into what usefulness is. This study attempts to gain insight into how Dooyeweerd’s aspects might be used to gain such insight.

The activity in this study is to reconceptualize constructs from Yousafzai et al.’s (2007) collection. To do this, the source of each construct is sought, so as to obtain a good definition or characterization of the construct in original text. That text is analysed to find what is most meaningful in what it is trying to put across about concepts relating to IS use that are behind the construct and related items in source papers were used to check or fill out the meaning of the concepts. Dooyeweerd’s aspects are used as a reference point in this process, as a categorization of ways in which things can be meaningful, with each relevant phrase being subjected to the question “Which aspect(s) best expresses what this phrase is trying to say?” Aspectual interpretation happened based on our intuition. The result is identification of one or more important aspects for each construct. In case of any conflict between the main aspect extracted from definition and the aspect understood from source paper items, we relied on the meaning hidden in the source paper.

5. Reinterpreting the constructs of PU

39 constructs are analyzed. For each one the main aspect is given and then possibility of having other aspects for them is examined.

Implementation gap

Implementation Gap in conceived by Chau (1996) as a possible gap between existing skills and knowledge that users have. The gap is meaningful as to be filled, which is a purposive action of achievement, a functioning in formative aspect. Other secondary aspects also play their part. The wider the gap between old and new skills, the longer will be the time likely to be needed for individual users to learn new skills and adapt to new work procedure which indicates his emphasize on time as a limited resource; that is a functioning in economic aspect. Responsibility for removing the implantation gap is juridical aspect and anxiety of users about the gap is a functioning in the sensitive aspect.

Internal computing support

Internal Computing Support is defined as “the technical support by individuals or groups with computer knowledge who are internal to small firms” (Igbaria et al, 1997). Little internal support for personal computing is available to users in small firms; however in small firms the lack of resources and technical sophistication precludes the creation of an information centre or PC support function. Informal support, in the form of help from users in other functional areas, manuals, purchased books, and help screens, is often the only form of support available. What seems meaningful to this is the going beyond what is due, a generosity, which is a functioning in ethical aspect. Important is the attitude of people who are to support the usage of the system. The quality of relationship among people is important in such Internal Computing Support, which suggests secondary functioning in social aspect.

Training

Training is an opportunity to learn about an innovation, thereby reducing uncertainty; also training enables the development of self-efficacy with respect to the innovation (Agarwal et al, 1996). As individuals become more skilled and comfortable in using the IS they better understand the it and its benefits (Riemenschneider and Hardgrave, 2003). This involves deliberate development and shaping of people’s skills, which is functioning in the formative aspect. Agarwal and Prasad (1999 and 2000) distinguish unstructured from structured training; structured training involves a precise idea of what is due to trainee and others (juridical aspect) while unstructured training involves self-giving (ethical aspect) and can be more fun (aesthetic aspect).

Internal computing training

Internal Computing Training refers to the amount of training provided by other computer users or computer specialists in the company (Igbaria et al. 1997). Prior research reported that training promotes greater understanding, favorable attitudes, more frequent use and more diverse use of applications in small firms. It is also reported that user training had a significant effect on the decision-making satisfaction of small firm managers who develop their own applications. Internal Computing Training is a functioning in the formative aspect because it is a shaping of the skills of people. Internal Computing Training also relies on people relationships (social aspect) and when it happens users are helped both in formal and in informal ways that shows juridical and ethical aspects respectively.

Job insecurity

Agarwal and Prasad (2000) report the result of a study focused on the issue of facilitating the movement of experienced programmers to become users of new programming languages. Job Insecurity is associated with the rapidly changing industrial structure and with greater susceptibility to innovations that are well publicized in the media. The main way that Job Insecurity is meaningful is in terms of financial resources, so it meaningful in the economic aspect. Also meaningful in Job Insecurity are people’s confidence in remaining in the market and being a bread winner (pistic aspect) and what should be there for people (juridical aspect).

Transitional support

Transitional Support in Chau’s (1996) study is about facilitating transition from the old to the new; in their study it refers specifically to software development and its tools. If such support is primarily dependent on generous attitudes then Transitional Support is meaningful in the ethical aspect. If Transitional Support is seen as what is due to users, it is meaningful in the juridical aspect. It involves a “network of support” involving formal and informal relationships among human beings, and hence has a social aspect too.

Accessibility

System Accessibility refers to the availability of resources for accessing the website, such as PC, modem and on-line services (Thong et al, 2002). Resources are meaningful in the economic aspect. Also this construct is meaningful in the juridical aspect, since the requisite resources are due to the users.

Access cost

Access Cost is defined by Shih (2004) to include the network speed and the cost of accessing the internet. For example the cost of accessing the web is an important part of searching costs for consumers using the e-market. Consumers prefer to evaluate the effectiveness of e-shopping based on its benefit and costs (Shih, 2004). This construct is meaningful in the economic aspect.

Compatibility

Compatibility is defined as “the degree to which an innovation is perceived as being consistent with the existing values, needs, and past experiences of potential adopters” (Moore and Benbasat, 1991; Agrawal and Prasad, 1997). This is another way of speaking of harmony in the sense of the aesthetic aspect. The juridical aspect tinge of due and obligation may also be sensed as a secondary aspect.

Convenience

Examining the subjects and constructs added to TAM in a more hedonic type of environment, Childers et al. (2001) believe that perception of Convenience is manifested by the opportunity to shop at home 24 hours, 7 days a week. Therefore interpreting this perception of convenience as an opportunity for users to save time is an economic aspect. They also state convenience includes `where’ a consumer can shop, which is the spatial aspect.

Image

Image refers to the perception that using an innovation will contribute to enhancing the social status of a potential adopter (Agrawal and Prasad, 1997), and Moore and Benbasat (1991) believe it to be one of the most important motivations in adopting an innovation. Social status is mainly a functioning in social aspect.

Output quality

In their studies, Davis et al. (1992) assert that “Quality is judged by observing intermediate or end products of using the system, such as documents, graphs, calculations and the like”. The perceived output quality was measured by asking subjects to rate the quality of each of the following types of documents: resume cover letters for job applications, class papers and reports, and personal correspondence. For measuring perceived output quality users were asked if the charts and graphs they would make with software X would be professional looking, or if by using software X the effectiveness of the finished product would be high or low. The main aspect that makes this meaningful is the lingual aspect.

Perceived complexity

Complexity is defined as “the degree to which an innovation is perceived as being difficult to use and to understand” (Moore and Benbasat, 1991; Thompson et al, 1991). Venkatesh et al. (2003) introduces the concept of Effort Expectancy that is defined as “the degree of ease associated with the use of the system” (Venkatesh et al, 2003) and believe that Perceived Complexity and Perceived Ease of Use capture the same concept. Thompson et al. (1991) see the complexity as a result of time required for learning, doing mechanical operations, and the time that is taken for normal duties of users. All this suggests that Perceived Complexity is meaningful in the economic aspect.

Response time

Response Time of, for example, a web site refers to the time that user spends on waiting to interact with a site. In their study Lin and Lu (2000) believe that Response Time of a web site is an important factor in affecting the user’s beliefs about it. They maintain that web page providers not only have to make the content informative and timely, but they also need to design a speedy web page by not putting in unnecessary data that as it might jeopardize the display time. Response Time is therefore meaningful in the economic aspect.

Result demonstrability

Result Demonstrability is defined as “the tangibility of the results of using an innovation” (Agrawal & Prasad, 1997), including their observablity and communicability (Moore and Benbasat, 1991). Both ‘demonstrability’ and ‘communicability’ suggest the lingual aspect. There is also a social aspect by virtue of involving human beings in the demonstration.

Trialability

Trialability is defined as “the extent to which potential adopters perceive that they have an opportunity to experiment with the innovation prior to committing to its usage” (Agarwal and Prasad, 1997). Trialability is involves deliberate formation of the relationship with the innovation, which is a functioning in the formative aspect. Secondary aspects include the lingual, because such experimentation involves recording and retrieving, and the juridical aspect because the opportunity to have a tested system is due to the users.

Visibility

Visibility is defined as “the extent to which potential adopters see the innovation as being visible in the adoption context” (Agarwal and Prasad, 1997; Thong et al, 2002). For instance, when an individual user sees an innovation on almost all desks in all other parts of the organisation, it is obvious enough for them to say they have observed that the technology “is being used” by the colleagues. It seems that this observation is not just limited to our eyes as one of the sensory organs that refer to sensitive aspect, but the individual is distinguishing the technology through the process in mind. Visibility is therefore meaningful in the analytical aspect.

Computer anxiety

Computer Anxiety is defined as “the tendency of individuals to be uneasy, apprehensive, or fearful about current or future use of computer” (Brosnan ,1999; Roberts and Henderson ,2000). This speaks of emotion, which is meaningful in the sensitive aspect. However the apprehension is often caused by a threat to some value that the individual holds essential to her/his existence as a personality, which is meaningful in the pistic aspect. The juridical aspect could also be meaningful in that the threat might be seen as a result of retribution.

Computer literacy

Computer Literacy is about individual abilities and tool experience (Igbaria et al,1997). This suggests the formative aspect, which is further supported by the fact that being computer literate has also a history; basic skills, intermediate skills and advanced skills. ‘Literacy’ also suggests a lingual aspect. As it is playing role in determining user status in the context it is the social aspect as well.

Educational level

This construct refers to the level of education that is indicative of the potential adopter’s ability to learn (Agarwal and Prasad, 1999). More sophisticated cognitive structures, perhaps acquired through higher education, lead to greater ability to learn in a novel situation (Agarwal and Prasad, 1999), which indicates the formative aspect. However, in reality the ability to learn anticipates more sophisticated cognitive structure (lingual aspect).

Gender

In their study, above all Gefen and Straub (1997) points to the gender differences and maintain that in socio-linguistic research gender is a fundamental facet of culture. Gender is most obviously of the biotic aspect. However, in showing show that mode of communication may be perceived differently by the sexes, there is a lingual aspect. Studies show that men and women tend to use and understand language in different ways (Venkatesh et al, 2003) and men tend to adopt a pattern of oral communication that is based on social hierarchy and competition than women do.

Perceived developer responsiveness

Perceived Developer Responsiveness (PDR) is defined as “the extent to which developers were perceived as being responsive to improvement suggestions and bugs reported by users” (Gefen and Keil, 1998). They emphasize the developer’s willingness to invest in their relationship with the users, moving beyond what is due to users and not limited to supporting in a formal way. Therefore PDR is a functioning in ethical aspect, with a secondary juridical aspect.

Percieved resources

Perceived Resources are “the extent to which an individual believes that he or she has the personal and organisational resources needed to use an IS” (Mathieson et al, 2001). Resources could be either tangible or intangible, and in either type they are treated as limited. This makes Perceived Resources meaningful in the economic aspect.

Role with technology

This construct’s complete name is Role with Regard to Technology and refers to whether the user’s primary responsibility is to be a provider or a user of technology (Agarwal and Prasad 1999). It has implications for their general level of experience with computing technology. Being either a provider or user, they have a social role in their own society and are in relationship with each other. Therefore, Role with Technology is a functioning in social aspect. As such Role with Technology reaches out to formative aspect due to the level of knowledge and skills that are determinant of different roles.

Shopping orientation

Shopping Orientation in O’Cass and French’s (2003) study could refer either to the economic aspect of obtaining resources, or the aesthetic aspect of recreational shopping. However apart from the O’Cass and French (2003) study it seems that orientation is not just restricted to these two aspects, but also points to the socializing tendency of shopping, which is the social aspect. There is also a sense of fulfilling an experience in the online shopping activity, such as is observed in websites like eBay. However, we conclude that in this study Shopping Orientation is of the formative aspect since, whatever other aspect is involved, the user is achieving a goal.

Tenure in workforce

Prior work suggests that older workers and those with greater company tenure are more likely to resist new technologies, and workers with less work experience were more committed to the changes caused by the new technology (Agarwal and Prasad, 1999). One could say it is functioning in formative aspect that is reaching out to number of days (quantitative aspect), age of employees (biotic aspect) and worth of workforce (economic aspect).

Voluntariness

Voluntariness is “the extent to which potential adopters perceives that adoption decision to be non-mandated” (Agarwal and Prasad, 1997). Primarily it is a functioning in the ethical aspect since it has a lot to do with willing attitude to choose what is not compulsory for them. However it could also be relevant to our courage (pistic aspect), and to what used to be a due before that (juridical aspect). It could be joyful (aesthetic aspect) or could be symbolic (lingual aspect).

Arguments for change

Argument for Change was measured then adopted by Jackson et al. (1997) to be added to Perceived usefulness. Argument in philosophy is the most basic complete unit of reasoning, or an atom of reason, but Argument for Change is more linked with communicating between people. Thus this construct is a functioning in the lingual aspect. Since it takes place among people it is a functioning in the social aspect too.

External computing training

This construct refers to the amount of training provided by friends, vendors, consultants, or educational institutions external to the company Igbaria et al. (1997). Compared with larger firms, small firms usually cannot afford to employ internal staff with specialized computer expertise, so to some extent they rely on support from outside the organisation. Given the information about the context of study, external computing training is a functioning in formative aspect. Also, one could argue that here formative aspect reaches out to the social aspect because of the relationships among people, to the juridical aspect, because of the contract that exists between two or more parties, to the ethical aspect because of the attitude that, for example, friends may show for helping their colleagues.

Facilitating condition

Facilitating condition is defined as “the degree to which an individual believes that an organisational and technical infrastructure exists to support use of the system” (Venkatesh et al, 2003). This construct was measured by asking questions concerning guidance which was available to the users in a selection of the system; specialized instruction concerning the system was available to the users; a specific person or group is available for assistance with system difficulties. These questions indicate that conditions that are facilitating the use of a system go beyond what is appropriate (i.e. juridical aspect) for the users, which suggests we could see this construct is a functioning in the ethical aspect.

Situational normality

Situational Normality is defined by Gefen et al. (2003) as “an assessment that the transaction will be a success based on how normal and customary the situation appears to be”. Gefen et al. (2003) suggest that Situational Normality is part of System Trust because, for example, perception of what is proper and normal in online shopping situation is helpful for shaping the trust between user and the system. Situational Normality thus assures people that everything in the setting is as it ought to be and that a shared understanding of what is happening exists. This suggests that Situational Normality is a functioning in the juridical aspect.

Subjective norm

Subjective Norm is defined as a “person’s perception that most people who are important to her think she should or should not perform the behaviour in question” (Fishbein and Azjen, 1975 cited in Venkatesh et al., 2003). In fact the emphasis is on the individual’s perceptions of normatively appropriate behaviour with regard to the use of system (Venkatesh et al, 2003; Venkatesh and Davis, 2000). Therefore the juridical aspect is an one important aspect that gives meaning to Subjective Norm. However, since social relationship play an important part, the social aspect is equally important.

Social influence

Social Influence has also been called ‘social pressure’ and ‘social norms’ by Thompson et al. (1991) and Venkatesh et al. (2003). Social Influence has its roots in Subjective Norm in the context of use, as is recognised in many studies. Social Influence, like Subjective Norm, is most meaningful in the social and juridical aspects.

Social pressure

Individuals may use micro computers not because of their usefulness or the enjoyment derived, but because of the perceived social pressure. Such pressure may be perceived as coming from individuals whose beliefs and opinions are important to them such as supervisors, peers and subordinates (Igbaria et al, 1996). They use the system because they think they will be perceived by the people who are important to them as technologically sophisticated. Igbaria et al. (1996) use Social Pressure to refer to Subjective Norm (Anandarajan et al, 2000 and 2002; Venkatesh and Davis, 2000)j, suggesting that both the juridical and social aspects are important.

Task-technology fit

Task-Technology Fit (TTF) is “the degree to which a technology assists an individual in performing his or her portfolio of tasks” (Goodhue and Thompson, 1995). It is the ability of IT to support a task, which implies matching of the capabilities of the technology to the demands of the task. If by fit we assume integration and matching between technology and task then it could bear the meaning of harmony that is the aesthetic aspect. However there is also an important juridical aspect, in that Task-Technology Fit contains an idea of obligation and appropriateness.

Task characteristics

Tasks are defined as “the actions carried out by individuals in turning inputs into outputs” (Goodhue and Thompson, 1995). Task itself is meaningful in the formative aspect, but the emphasis seems to be on distinguishing its characteristics, which means the analytical aspect is the main one. Task characteristics are those that inspire a user to rely on certain aspects of the IT, and is for a task of any type with any details and importance.

Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy is defined as “people’s judgment of their capabilities to perform a given task, which in turn determines which actions to take, how much effort to invest and how long to preserve” (Yi and Hwang, 2003). Such judgment may be seen as a functioning in the pistic aspect since it is a vision by people of who they are. This is confirmed by Yi and Hwang’s questionnaire, which mostly asked users about their confidence toward using the system.

Trust

Trust has many different definitions and connotations across research areas and usually takes place in highly uncertain situations between two parties (Suh and Han, 2002). Among different definitions, Trust is defined as “the willingness to depend on another party with having hoped to achieve a blossoming relationship is common” (Suh and Han, 2002 and 2003). Users believe in what they want to achieve and have reasonable confidence for their willingness to engage in using the system. Therefore Trust is a functioning in the pistic (faith) aspect.

Perceived enjoyment

Perceived Enjoyment refers to “the extent to which the activity of using a system is perceived to be personally enjoyable in its own right aside from the instrumental value of the technology” (Davis et al, 1992). The sense of enjoyment in using a given system helps people feel confident about their ability to successfully execute the requisite action. The enjoyment was examined by Davis et al. (1992) in terms of whether using the proposed system is fun or pleasant and if users find it enjoyable when they start working with it. Therefore, this construct is meaningful in the aesthetic aspect.

5.1 Summary of findings

5.1 Summary of findings

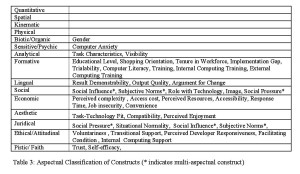

Table 2 brings together the results from the above analysis. The first column shows all the analyzed constructs and the second column shows their main aspects. Main aspects were derived via aspectual analysis an understanding of their kernel meaning plus the intuition of the researcher. Notice that some constructs are the manifestation of two main aspects, which is mainly because the two aspects were considered as equally important to the desired construct. For many constructs there was a chance of finding other aspects.

6. Discussion

6.1 Aspects review

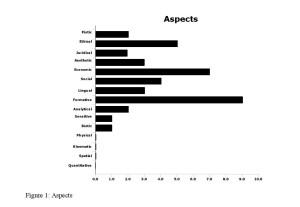

To have a better view of comparison between the different aspects the bar chart in Figure 1 presents Table 2 visually, showing how many times each aspect has been the main sphere of meaning for different constructs. Since only 39 of the constructs out of 70 were analyzed, these results must be taken as only indicative, so only brief discussion occurs here to indicate the kind of issues that might arise with a fuller study.

The first thing to notice is that three aspects are much more prevalent than others, the formative, economic and ethical. That is, the IS community has a tendency to formulate constructs that are meaningful in those three aspects more than in others. Why might this be? The interest in the formative aspect is easily explained by the fact that ‘usefulness’ is defined in ways that emphasise the formative aspect, such as “The degree to which an individual believes that using a particular system would enhance his or her job performance” (Davis, 1989), and we are dealing with technology. Interest in the economic aspect is easily explained by the fact that most construct-generating research has been carried out in the context of business, or at least organizational, requirements, and by the fact that TAM originally had a business purpose.

The high interest in the ethical aspect is somewhat surprising, in an industry and discipline that is not known for its ethical prowess. It should be noted, however, that ‘ethical’ to Dooyeweerd does not refer to corporate social responsibility nor what is usually deemed ‘ethics’ in IS, but refers to self-giving love, to generosity, to going beyond the call of duty, to attitude that is self-giving rather than selfish. The interest in the ethical aspect does not imply good functioning in it, but merely that those who created the constructs recognized its importance. The constructs that are defined mainly by the ethical aspect include Voluntariness, and four constructs by which the user feels supported in their use (Transitional Support, Perceived Developer Responsiveness, Facilitating Condition, and Internal Computing Support). Such support could be deemed of the juridical aspect (a right that users expect) but in practice users find generous support, with a good attitude, much more desirable, and this is of the ethical aspect.

Second, we ask why certain aspects are missing or low, namely from quantitative to psychic. This is explained by the fact that the first three are mathematical aspect and are seldom the most important aspects in human constructs. The physical, biotic and psychic are pre-human aspects, and of less interest when considering usefulness unless the application happens to relate to them.

Then attention may be given to the remaining aspects. That the social and lingual aspects are slightly higher might reflect the fact that research into usefulness relates to information (lingual aspect) in organizations (social aspect), but the full study might show something else. There seem to be no surprises other than the high interest in the ethical aspect.

6.2 Quality of constructs

Table 2 shows that many constructs are allocated one single aspect, but some are allocated several (multi-aspectual constructs). Among them there are constructs for them the main aspect is prone to the change, called ‘swinging constructs’.

6.2.1 Single aspect constructs

Table 2 shows thirteen constructs that are only one aspect. This implies they are meaningful mainly in one way, which suggests that these constructs are likely to be well-formed and aspectually clear and strong enough to be representative of one aspect. For example, Perceived Enjoyment is the aesthetic aspect, and Access cost is the economic aspect. Dooyeweerd does, of course, hold that all things exhibit all aspects when part of concrete situations, so for example Perceived Enjoyment is also formative (achievement that is enjoyed), but when generalized across situations, it is mainly one aspect that is meaningful in the case of these constructs.

Since aspects are irreducible to each other in their meaning, it follows that constructs meaningful in separate aspects should not be confused with each other; for example, Perceived Enjoyment (aesthetic aspect) should never be explained away in terms of Access Cost (economic aspect), nor vice versa, even though there might be some link between them. On the other hand, as discussed below, constructs that share a main aspect might be considered together.

6.2.2 Multi-aspectual constructs

Many constructs have more than one aspect in which they are meaningful, usually main one and some secondary ones. In some of these all aspects are necessary, and we call them multi-aspectual constructs. For example, Subjective Norm (SN) is a about the influence of people’s belief in our social environment on our behavioral intention. For this construct there are always at least two people as the prerequisite of shaping SN. So this is about ‘we’ (social Aspect) rather than ‘I’. SN is also about the importance we attribute to other’s norm, which demands an appropriate response (juridical aspect). Unlike swinging constructs (below), which lack clear explanation of their context, SN is always both Social and Juridical aspect in all contexts where it is relevant.

SN is relevant to compulsory use. In a context in which using a system is voluntary, SN does not make sense, because the juridical aspect of it fades away and its Social aspect is not as significant as the willingness (ethical aspect) to use the system. As we move from one context to the other, SN gives place to another construct, Voluntariness. This might account for why Davis (1989) excluded SN from TAM even though it is included in the Theory of Reasoned Action on which TAM is based.

6.2.3 Swinging constructs

For some constructs that exhibit more than one aspect it is not possible to decide which the main one is. For example, Transitional Support looks like a pendulum swinging between ethical and juridical aspects, and at the same time there are individuals or group of people with specific role and responsibilities and relationships (Social aspect) poking this pendulum from either side.

Likewise, Facilitating Condition is about factors in the environment that hinder or help the use, we have the swinging between ethical and juridical aspect. Unfortunately, the context in which facilitating conditions are tested is not very well described in Venkatesh et al, (2003), leaving some ambiguity. If help is offered by those who are paid to give it (help desks), this is juridical, but if it is offered generously beyond the call of duty, such as by hard-pressed colleagues, it is ethical aspect.

For Compatibility we chose aesthetic aspect but are not satisfied with it; it might be juridical if we are to match innovation with current needs and values. Internal Computing Supports swings between ethical and social. Job Insecurity swings between economic, juridical and pistic aspects.

The ambiguity of swinging constructs occurs because the sources did not have detailed information about the context, and we were not able to make up our mind what aspect could be the main one.

6.3 Reclassifying constructs

Yousafzai et al. (2007) groups the 70 constructs into three specific categories (organisational, system and personal characteristics), with many other constructs under ‘Other Variables’. The aspects may be used as more finely tuned categories, in which constructs are grouped according to which aspect makes them most meaningful. Table 3, which is Table 2 reversed, show which constructs have a given aspect as their main one.

This provides a more precise classification than Yousafzai, and has the advantage that there is no ‘Other’ category. Each construct is expected to be meaningful in at least one of the above ways. All three of Social Pressure, Social Influence and Subjective Norms exhibit both social and juridical aspects. It addresses Problem 6, in that it bases categorization on a philosophical reflection on spheres of meaning, from which all other categorizations arise. For example, hedonic versus instrumental use (Van der Heijden 2004) refers to use governed by the aesthetic versus formative aspects. Chau’s (1996) reference to near- and long-term repercussions refer to middle and later aspects since later aspects operate over longer timescales (Basden 2008).

The constructs that share an aspect might have an internal link between them, and this might assist understanding how they relate to each other. Thus, for example, Trust and Self-efficacy sharing the pistic aspect raises the question of whether they are linked. This brings a number of specific questions to the surface. For example, it may be that if users are confident they are able to use the IS, are they likely to trust themselves, trust others or trust the system? Raising such questions about constructs that share a main aspect could provide fruitful material for future research.

6.4 Towards a method for reconceptualizing constructs

Dooyeweerd’s aspects were applied to understanding the meaning of the constructs added to PU. Each of the 39 constructs has been ‘opened up’ by finding in which aspects it is most meaningful according to the author who introduced it. The meaning of these constructs has been made clearer and they have been reclassified in a way that brings to the surface some of the links between them. This allows us to reconceptualizing each in the four ways recommended by Barki (2008).

The exercise of assigning aspects to a construct forces us to clarify distinct meanings, which may be used to define it. For a single-aspect like Perceived Enjoyment (aesthetic aspect) this is quite straightforward, though the process of definition cannot cease once an aspect has been assigned. Doing so invites others to question whether other aspects are important – for example, it might also be a social and perhaps even pistic issue – but the clarity of such questioning and debate that follows is enhanced by having initially assigned an aspect.

When several aspects are found and assigned they can indicate the main dimensions of the construct (again making a clear proposal that invites critique). That the aspects are irreducibly distinct and yet also interrelated provides a basis for discussing the relationship between dimensions, and possibly for a richer discussion than even Barki envisaged. In particular, aspects are interrelated in respect of an entity, event or behaviour, since one aspect (qualifying aspect) governs the thing’s main reason for existence and another aspect (founding) governs the coming-into-being of the thing. For example, the qualifying aspect of Image is social and possibly pistic while its founding aspect is lingual.

With ‘swinging’ constructs the multiple aspects might indicate different contexts in which the construct might be applied. For example, Job Insecurity swings between economic, juridical and pistic aspect, depending on whether the main concern is to do with finance, rights or self-worth, which itself depends on context.

That some constructs are not attributes but are constituted as the outcome of human behaviors (Barki 2008) can be made clearer by aspectual analysis that sees the aspects as modes of (human) functioning. For example, social influence and social pressure are both social functioning, i.e. functioning governed by the social aspect. When we ask what is the difference between them, which we feel intuitively, we find we must bring in juridical functioning: pressure has the connotation of inappropriateness while influence can be more positive in that aspect.

This approach can address each of the seven problems exhibited by Yousafzai et al.’s (2007) collection of constructs.

* The unmanageability of Yousafzai et al.’s set: Dooyeweerd’s suite of aspects is more manageable.

* the list of constructs is not likely to be complete: Dooyeweerd’s suite of aspects aspires to cover the entire range of meaningfulness that generates constructs.

* Some constructs are over-specific in use or interest: Dooyeweerd’s aspects can show what is generic about them.

* Some constructs are ambiguous: Applying Dooyeweerd’s aspects helps to clarify meaning.

* There are overlaps between some of these constructs: Aspectual analysis can reveal where the overlap occurs and indicate how to resolve it.

* as centring on an aspect, and there are other aspects.

* Most studies were within a limited culture: Dooyeweerd’s aspects transcend culture.

6.5 On employing Dooyeweerd’s aspects

Applying Dooyeweerd’s philosophy to reconceptualizing constructs was not always an easy task. Dooyeweerd’s aspects are attuned to everyday experience so they are suited to analysing multi-aspectual situations of human activity because all aspects can be expected to be present. When they are applied to understanding extant constructs, which have been formulated as part of theory of, IS use, it might not be so easy. It is true that even these constructs exist and pertain within the horizon of the aspects, but those who formulated them have deemed certain aspects most meaningful, and the challenge is to find out which ones. Though words with which they are introduced give some indication, words carry many hidden connotations. For this reason it was important to seek out the original sources and try to work out what was meaningful to them.

Knowing the kernel meaning of each aspect was not enough for understanding what meaning each construct was conveying. Having a broader intuition of different central themes of each aspect and differences between neighboring aspects helped to understand each construct. Nevertheless, this study, of about half the constructs of Yousafzai (2007), demonstrates the feasibility of doing this and that this application of Dooyeweerd’s aspects has been fruitful to the new wave of opening PU’s ‘Black Box’ and especially of providing a way of reconceptualizing constructs.

7. Discussion and conclusion

7.1 Summary of research

This study discussed the possibility of applying Dooyeweerd’s aspects to Perceived Usefulness by seeking to understand in which sense the constructs added to PU as external variables are meaningful. When PU was questioned by scholars in the field, its complexity and vagueness became plain and Yousafzai et al. (2007) collected 70 constructs that resulted. To some extent, this opened the ‘Black Box’ of PU (Benbasat and Barki 2007), allowing us to look at what is inside it and letting all the complexities be revealed. But at the same time, it became a Pandora’s Box that released a lot of complexities. This study has demonstrated a way of opening the box that manages the complexities into fifteen aspects, in addition to possibly revealing other constructs which have not yet been discussed in the literature.

7.2 Limitation of this study and future work

The most obvious limitation of this study is that it covers only 39 of Yousafzai’s 70 constructs. This must be rectified before any sound reconceptualization and reclassification of constructs can be completed, but it is sufficient to show that this aspectual approach is promising, which is the aim of this paper. It might be, however, that some original sources are inaccessible.

Moreover, the analysis has been brief and indicative rather than exhaustive. Some residual ambiguity may be detected even in the aspectual analysis of the constructs. Much of the reason for this is that the original sources contained too little information to make the meaning of their constructs clear. Sometimes it was necessary to read between the lines. Some of the reason is that the exercise of aspectual analysis is ever a learning experience, which changes the analyst’s understanding of the very aspects s/he is applying. Dooyeweerdian aspectual analysis is a relatively new technique and a body of expertise is still being built up.

7.3 Contributions

The main contribution of this paper is to propose a method for reconceptualizing extant constructs of IS use, prior to carrying out the full reconceptualization. The method – aspectual analysis of constructs – operationalizes each of the four parts of Barki’s (2008) approach. It also potentially addresses each of the seven problems exhibited by the collection of constructs compiled by Yousafzai et al. (2007).

However, as a pilot for the fuller study, this study can indicate what kind of contribution can be made in the area of IS use, and especially in relation to Davis’ (1989) Technology Acceptance Model. Specifically, while TAM and related studies are mainly concerned with testing hypothetical links between predefined constructs, this study contributes to preparing the constructs for such testing, by reconceptualizing and even perhaps conceptualizing them. Dooyeweerd’s aspects provide the basis for a better categorization of constructs because they are fundamental ways in which things are meaningful. Since Dooyeweerd’s suite of aspects aspires to complete coverage of meaning, it provides a basis for identifying missing constructs. In its notion of interaspect coherence and of qualifying and founding aspects, Dooyeweerd’s philosophy provides a way of reflecting on the possible relationships between constructs. Finally, since the aspects are also spheres of law, each construct based on them will contain an innate normativity, rather than being purely descriptive, and this can perhaps yield models of IS use that are more useful in guiding evaluation and design. Though this study has confined itself to Perceived Usefulness, the method it explores could be applied to any other construct of IS use.

The study might also make a contribution to Dooyeweerdian scholarship itself, in that it differs from several other studies. The field of information systems is highly interdisciplinary and hence can be an excellent exemplar for applying, testing and refining our understanding of the aspects in Dooyeweerd’s suite. Whereas Basden (2008) explores this possibility, it does so at a broad level, while this study is much more detailed. Whereas Basden (2008) generates ideas from Dooyeweerd’s philosophy itself, this study begins with the findings of an extant body of research. Eriksson (2001) applied Dooyeweerd’s aspects to specific situations, as a case study; this study applies Dooyeweerd’s aspects to abstracted, theoretical constructs. Basden & Wood-Harper (2006) apply aspects to constructs, but they are constructs devised by one thinker, Peter Checkland, and so exhibit a coherence and completeness, and also elegance, that comes from good reflective thought. By contrast, this study applies Dooyeweerd’s aspects to constructs arising from many disparate thinkers, a collection which is much more numerous and exhibits incoherence and incompleteness. In such ways, this study might make a contribution to understanding a practice of aspectual analysis.

7.4 This paper situated among others

Why is it useful to reconceptualize constructs of IS use that have been discussed in the theoretical literature? The reason is that IS use is still not well understood, (Mishra & Agarwal, 2009). What has been extensively studied, and for which constructs have been formulated, has not been IS use itself but acceptance of information technology, prior to on-going use. Unless IS use as such is well understood, the attempt to gain benefits from IS use will remain ad hoc and subject to high failure rates. As a result, IT gets a bad name and is resisted even when it has been accepted.

Many constructs related to technology acceptance are nevertheless relevant to IS use – for example Usefulness and Ease of Use themselves – even if they need reconceptualizing in such a context. This study is oriented to IS use rather than acceptance and, as a first step, has explored a method by which constructs can be reconceptualized. The next step is to make a fuller study of constructs, more expressly directed towards IS use itself. This can take in not only all 70 collected by Yousafzai et al. (2007) but also those investigated by the usage community inspired by Delone & McLean (1992) and similar thinkers.

However, all these presuppose extant constructs. Basden & Ahmad (2011) in this collection of papers argue that extant constructs are theoretically oriented and are of interest to researchers and managers rather than being oriented to the everyday experience of actual IS users and their work colleagues, and they suggest applying Dooyeweerd’s aspects directly to the situation of IS use itself. Ahmad & Basden (2011), again in this volume, explore a method for doing this. So those papers can complement this one. All three papers join together in exploring how Dooyeweerd’s aspects can help us understand IS use better.

The approach in those two papers tries to ignore extant constructs, and understand IS use directly, but perhaps at the cost of not being able to hold discourse with extant literature. The approach in this paper might not be so faithful to the actual situation of use, but it introduces Dooyeweerd’s aspects in a way that maintains discourse with the extant literature.

Acknowledgement

The Authors would like to thank Dr Beryl Burns for the valuable comments on this paper, and the participants in the 2001 IIDE/CPTS Annual Working Conference.

About the authors

i. Sina Joneidy – Salford Business School, University of Salford, Salford, UK. Sina.joneidy@gmail.com

ii. Andrew Basden – Salford Business School, University of Salford, Salford, UK. A.Basden@salford.ac.uk

REFERENCES

Agarwal, R. and Prasad, J. (2000). A field study of the adoption of software process innovations by information system professionals, IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, Vol. 47, No. 3, pp. 295-308.

Agarwal,R. and Prasad,J. (1999). Are individual differences germane to the acceptance of new information technologies?. Decision Sciences, Vol. 30, No. 2, pp. 361-391.

Agarwal, R. and Prasad, J. (1997). The role of innovation characteristics and perceived voluntariness in the acceptance of information technologies. Decision Sciences, Vol. 28, No. 3, pp. 557-581.

Agarwal, R. Prasad, J. and Zanino, M. (1996). Training experiences and usage intentions: a field study of a Graphical Interface. International Journal of Human-Computer studies, Vol. 45, pp. 215-241.

Ahmad, H. & Basden, A. (2011). Down-To-Earth Issues In (MANDATORY) Information System Use: PART II – Approach To Understand and Reveal Hidden Issues. In: Haftor, D.M. and Van Burken, C.G. (eds.) (2011) “Re-Integrating Technology and Economy in Human Life and Society”, Proceedings of the 17th Annual Working Conference of the IIDE, Maarssen, May 2011, Volume II, Amsterdam: Rozenberg Publishers

Anandarajan, M., Igbaria, M. and Anakwe, U. P. (2000). Technology acceptance in the banking industry. Information Technology and People, Vol. 13 No. 4, pp. 298-312.

Anandarajan, M., Igbaria, M. and Anakwe, U. P. (2002). IT acceptance in a less-developed country. International Journal of Information Management, Vol. 22 No. 1, pp. 47-65.

Barki, H. (2008). Thar’s Gold In Them Thar Constructs. The DATA BASE for advances in Information Systems, Vol. 39, No. 3,pp. 9-20.

Barki,H. and Hartwick, J. (2004). Conceptualizing the construct of interpersonal conflict. International Journal of Conflict Management, Vol. 15, No.3, pp.216-244.

Basden, A. (2001). A philosophical underpinning for IT evaluation. Proceedings of the 8th European Conference on IT Evaluation, pp. 109-116.

Basden A, Wood-Harper AT. (2006) A philosophical discussion of the Root Definition in Soft Systems Thinking: An enrichment of CATWOE. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 23:61-87.

Basden, A. (2008). Philosophical Frameworks for Understanding Information Systems. Hershey, USA: IGI Global.

Basden, A. & Ahmad, H. (2011). Down-To-Earth Issues in (Mandatory) IS Use; PART I – Types of Issue. In: Haftor, D.M. and Van Burken, C.G. (eds.) (2011) “Re-Integrating Technology and Economy in Human Life and Society”, Proceedings of the 17th Annual Working Conference of the IIDE, Maarssen, May 2011, Volume II, Amsterdam: Rozenberg Publishers

Benbasat, I. and Barki, H. (2007). Quo Vadis, TAM?. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, Vol. 8 No. 3, pp. 211-218.

Brosnan, M. J. (1999). Modelling Technophobia: a case for word processing. Computers in Human Behaviour, Vol. 15 No. 2, pp. 105-121.

Bunge M, (1979). Treatise on Basic Philosophy, Vol. 4: Ontology 2: A World of Systems. Reidal, Boston.

Chau, P. K. (1996). An empirical investigation on factors affecting the acceptance of CASE by system developers. Information and Management, Vol. 30 No. 6, pp. 269-280.

Childers, T., Carr, C., Peck, J. and Carson, S. (2001). Hedonic and Utilitarian motivations for online retail shopping behaviour. Journal of Retailing, Vol. 77 No. 4, pp. 511-535.

Davis, F. (1986). A technology acceptance model for empirically testing new end-user information systems: theory and results. Doctoral Dissertation, MIT Sloan School of Management, Cambridge, MA.

Davis, F. (1989). Perceived usefulness, Perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, Vol. 13 No. 3, pp. 319-340.

Davis, F., Bagozzi, R. P. and Warshaw, P. R. (1992). Extrinsic and Intrinsic motivation to use computers in the workplace. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, Vol. 22 No. 14, pp. 1111-1132.

Davis, F, Venkatesh, V,(1995). Measuring User Acceptance of Emerging Information Technologies: An Assessment of possible Method Biases. Proceedings of the 28th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, pp.729-736.

DeLone, W. H., & McLean, E. R. (1992). Information Systems Success: The Quest for the Dependent Variable. Information Systems Research, Vol.3, No.1, pp. 60-95.

Dooyeweerd H. (1955). A New Critique of Theoretical Thought, Vol. I-IV, Paideia Press (1975 edition), Jordan Station, Ontario.

Eriksson, D. (2001). Multi-Modal Investigation of a Business Process and Information System Redesign: A Post-Implementation Case Study. Systems Research and Behavioural Science, Vol. 18 No. 2, pp. 181-196.

Foucault, M. (1972). The Archaeology of Knowledge (tr. A.M. Sheridan Smith). London: Routledge.

Gefen, D. and Straub, D. W. (1997). Gender differences in the perception and use of e-mail: an extension to the TAM. MIS Quarterly, Vol. 21 No. 4, pp. 389-400.

Gefen, D. and Keil, M. (1998). The impact of developer responsiveness on perceptions of usefulness and ease of use: extension of TAM. The Data Base, Vol. 29. pp. 35-49.

Gefen, D., Karahanna, E. and Straub, D. W. (2003). Trust and TAM in online shopping: an integrated model. MIS Quarterly, Vol. 27 No. 1, pp. 51-90.

Goodhue, D. L. and Thompson R. L. (1995). Task-technology fit and individual performance. MIS Quarterly, Vol. 19 No. 2, pp. 213-236.

Habermas, J. (1972). Knowledge and Human Interests, tr. J.J. Shapiro. London: Heinemann.

Hartmann, N. (1952). The New Ways of Ontology. Chicago University Press.

Igbaria, M., Zinatelli, N., Cragg, P. and Cavaye, A. (1997). Personal computing acceptance factors in small firms: a structural equation model. MIS Quarterly, Vol. 21 No. 3, pp. 279-302.

Igbaria, M., Parasuraman, S. and Baroudi, J. (1996). A motivational model of microcomputer usage. Journal of MIS, Vol. 13 No. 1,pp. 127-143.

Jackson, C.,Chow, S. and Robert, A. (1997). Towards an understanding of the behavioural intention to use an IS. Decision Science, Vol. 28 No. 2, pp. 357-389.

Kerlinger, F.N. and Lee, H.B. (2000). Foundations of Behavioural Research, 7th Edition. New York, NY: Thomson Learning

Lee, Y., Kozar, K.A. and Larsen, K.R.T. (2003). The Technology Acceptance Model: past, present, and the future. Communications of the AIS, Vol.12, pp.752-780.

Lin, J. C. and Lu, H. (2000). Towards an understanding of the behavioural intention to use a web site. International Journal of Information Management, Vol. 20 No. 3, pp. 197-208.

Mathieson, K., Peacock, E. and Chin, W. (2001). Extending the technology acceptance model: the influence of user resources. The Database, Vol. 32 No. 3, pp. 86-104.

Mishra, A. N., & Agarwal, R. (2009). Technological Frames, Organizational Capabilities, and IT Use: An Empirical Investigation of Electronic Procurement. Information Systems Research, pp.1-22.

Moore, G. C. and Benbasat, I. (1991). Development of an Instrument to measure the perceptions of Adopting an information technology Innovation. Information Systems Research, Vol. 2 No. 3, pp. 192-222.

O’Cass, A. and French, T. (2003). Web retailing adoption: exploring the nature of internet users web retailing behaviour. Retailing and Consumer Service, Vol. 10 No. 1, pp. 81-94.

Polanyi, M. (1962). Personal Knowledge: Towards a Post-Critical Philosophy. University of Chicago Press.

Riemenschneider, C. K. and Hardgrave, B. C. (2003). Explaining software development tool use with technology acceptance model. Journal of Computer Information Systems, Vol. 41 No. 4,pp. 1-8.

Roberts, P. and Henderson, R. (2000). Information technology acceptance in a sample of government employees. Interacting with Computers, Vol. 12 No. 5, pp. 427-443.

Saade, R. G. (2007). Dimensions of Perceived usefulness: Toward Enhanced Assessment. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, Vol. 5 No. 2, pp. 289-310.

Shih, H. P. (2004). An empirical study on predicting user acceptance of e-shopping on the web. Information and Management, Vol. 41 No. 3, pp. 351-369.

Suh, B. and Han, I. (2002). Effect of trust on customer acceptance of internet Banking. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, Vol. 1 No. 3. pp. 247-263.

Suh, B. and Han, I. (2003). The impact of customer trust and perception of security control on the acceptance of electronic commerce. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, Vol. 7 No. 3, pp. 135-161.

Thompson, R. L., Higgins, C. A., and Howell, J. M. (1991). Towards a conceptual model of utilization. MIS Quarterly, Vol. 15 No. 1,pp. 125-143.

Thong, J., Hong, W. and Tam, K-R. (2002). Understanding user acceptance of digital libraries: what are the roles of interface characteristics, organisational context, and individual differences? International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, Vol. 57 No. 3, pp. 215-242.

Van der Heijden, H. (2004). User Acceptance of Hedonic Information Systems. MIS Quarterly, Vol. 28, No.4, pp. 694-704.

Venkatesh, V. and Davis, F. (2000). A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: four longitudinal field studies. Management Science, Vol. 46 No. 2, pp. 186-204.

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M., Davis, G. and Davis, F. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: towards a unified view. MIS Quarterly, Vol. 27 No. 3, pp. 479-501.

Yi, M. Y. and Hwang, Y. (2003). Predicting the use of web-based information systems: self-efficacy enjoyment, learning goal orientation, and the technology acceptance model. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, Vol. 59 No. 4, pp. 431-449.

Yousafzai, Sh Y., Foxall, G R. and Pallister, J G. (2007). Technology acceptance: a meta-analysis of the TAM: Part 1. Journal of Modelling in Management, Vol. 2 No. 3, pp. 251-280.