ISSA Proceedings 1998 – Argumentation Explicitness And Persuasive Effect: A Meta-Analytic Review Of The Effects Of Citing Information Sources In Persuasive Messages

Argumentative explicitness is commonly acknowledged to be a normative ideal for argumentative practice, but advocates might fear that explicit argumentation could impair persuasive success. The question of the persuasive effects of argumentative explicitness is an empirical one, however. This paper addresses one aspect of this matter, by offering a meta-analytic review of the persuasive effects associated with one aspect of the degree of articulation given to an advocate’s supporting argumentation, namely, whether the advocate explicitly identifies the sources of supporting information.

Argumentative explicitness is commonly acknowledged to be a normative ideal for argumentative practice, but advocates might fear that explicit argumentation could impair persuasive success. The question of the persuasive effects of argumentative explicitness is an empirical one, however. This paper addresses one aspect of this matter, by offering a meta-analytic review of the persuasive effects associated with one aspect of the degree of articulation given to an advocate’s supporting argumentation, namely, whether the advocate explicitly identifies the sources of supporting information.

1. Background

Argumentative explicitness is one commonly-recognized normative good in the conduct of advocates. That is, it is normatively desirable that advocates explicitly articulate their viewpoints: “Evasion, concealment, and artful dodging . . . are and should be excluded from an ideal model of critical discussion” (van Eemeren, Grootendorst, Jackson, & Jacobs 1993: 173). Explicit argumentation is normatively desirable because explicitness opens the advocated view for critical scrutiny. But explicit argumentation might not be instrumentally successful, that is, persuasive, which gives rise to the question: what is the relationship between argumentative explicitness and persuasive effects?

One facet of this question has been addressed by O’Keefe (1997), who reviewed research concerning the persuasive effects of variations in the explicitness of a message’s conclusion (the degree of articulation of the message’s overall standpoint or recommendation). His review suggested that better-articulated message conclusions are dependably more persuasive than less-articulated ones.

This paper concerns the persuasive effects of variation in the explicitness of one facet of a message’s supporting argumentation, specifically, whether the advocate explicitly identifies the sources of provided information. A number of studies have addressed this question, though many of these have never been systematically collected or reviewed. The purpose of the present paper is to provide a meta-analytic review of this research.

Meta-analytic literature reviews aim at providing systematic quantitative summaries of research studies (Rosenthal 1991 provides a useful general discussion of meta-analysis). Traditional narrative literature reviews emphasize statistical significance (whether a given study finds a statistically significant effect), but this can be a misleading way of characterizing research findings; whether statistical significance is achieved is a matter of, inter alia, sample size. Meta-analytic reviews instead commonly focus on the size of the effect obtained in each study, with these then being combined to give an observed average effect (with an associated confidence interval). In this paper, the effect of central interest is the persuasive outcome associated with variation in information-source citation.

A number of studies relevant to this question are ones commonly characterized as studies of the effects of “evidence” in persuasive messages (e.g., McCroskey 1969; Reinard 1988). The question of interest in these studies is what difference it makes to persuasive effectiveness if the advocate provides evidence supporting the message’s claims. As Kellermann (1980) has pointed out, however, the concept of evidence invoked in this research is not carefully formulated and, correspondingly, evidence research has seen a large number of different experimental realizations of evidence variations (see Kellermann 1980: 163-164). Kellermann has argued quite pointedly for the importance of more careful conceptualization of the relevant message properties.

One of the message variations commonly represented in evidence research is information-source citation. That is, as part of manipulating the presence of “evidence” in a message, investigators have varied whether the message contains explicit identification of information sources. Thus in a number of studies, information-source citation has been manipulated simultaneously (that is, in a confounded fashion) with other variables (e.g., Harte 1972; McCroskey 1966).

The present review thus has a somewhat sharper focus than those in discussions of evidence, by virtue of being concerned specifically with information-source citation (cf., e.g., Reinard 1994). This more careful specification of the message property of interest has also made it possible to locate relevant research not commonly mentioned in discussions of evidence (e.g., Berger 1988). Moreover, given that some studies have manipulated information-source citation in tandem with other variables, the present focus permits one to distinguish cases in which only information-source citation is varied from cases that simultaneously vary information-source citation and other message properties; studies of such joint manipulations are of distinctive interest, precisely because they shed light on the question of the effects of combining information-source citation manipulations with other variations.

2. Method

Identification of Relevant Investigations

Literature search. Relevant research reports were located through personal knowledge of the literature, examination of previous reviews and textbooks, and inspection of reference lists in previously-located reports. Additionally, searches were made through databases and document-retrieval services using such terms as “documentation,” “evidence,” and “support” in conjunction with “persuasion” and “persuasive” as search bases; these searches covered material through at least January 1998 in PsycINFO, ERIC (Educational Resources Information Center), Current Contents, ABI/Inform, and Dissertation Abstracts Online.

Inclusion criteria. Studies selected had to meet two criteria. First, the study had to compare two messages varying in information-source citation; specifically, the study had to contrast a message that explicitly identified the sources of (at least some of) the message’s information (facts, opinions, and the like) and a message that presented the same information without such identifying source information. This criterion excluded studies that varied other aspects of the message’s explicitness, such as the explicitness of the overall conclusion (e.g., Hovland & Mandell 1952), the completeness with which supporting-argument premises or conclusions were articulated (e.g., Kardes 1988), and the like.

Second, the investigation had to contain appropriate quantitative data pertinent to the comparison of persuasive effectiveness or perceived credibility between experimental conditions. This criterion excluded studies that did not provide appropriate quantitative information about effects (e.g., Babich 1971; Kilcrease 1977; McCroskey 1967b, studies 2, 6, 11, 12, and 13).

Dependent Variables and Effect Size Measure

Dependent variables. Two dependent variables were of interest. The dependent variable of central interest was persuasiveness (as assessed through measures such as opinion change, postcommunication agreement, behavioral intention, and the like). When a single study contained multiple indices of persuasion, these were averaged to yield a single summary.

The other dependent variable was credibility (as assessed though, e.g., measures of competence, trustworthiness, believability, and the like). Where multiple indices of credibility were available, these were averaged.

Effect size measure. Every comparison between a message providing information-source citations and its less explicit counterpart (without such citations) was summarized using r as the effect size measure. Differences favoring explicit messages were given a positive sign; differences favoring inexplicit messages were given a negative sign.

When correlations were averaged across several dependent measures, the average was computed using the r-to-z-to-r transformation procedure, weighted by n. Wherever possible, multiple-factor designs were analyzed by reconstituting the analysis such that individual-difference factors (but not other experimental manipulations) were put back into the error term (following the suggestion of Johnson 1989).

When a given investigation was reported in more than one outlet, it was treated as a single study and analyzed accordingly. The same research was reported (in whole or in part) in Cathcart (1953) and Cathcart (1955); in Harte (1972) and Harte (1976); in Hayes (1966) and Hayes (1971); in Luchok (1973) and in Luchok and McCroskey (1978), recorded here under the latter; in McCroskey (1967b, Study 1), McCroskey (1966, pilot study), McCroskey (1967a), and in McCroskey and Dunham (1966, Experiment 1); in McCroskey (1967b, Study 2) and in McCroskey and Dunham (1966, Experiment 2); in McCroskey (1967b, Study 3) and in Holtzman (1966); in McCroskey (1967b, Study 4) and in McCroskey (1966, major study I); in McCroskey (1967b, Study 5) and in McCroskey (1966, major study II); in Ostermeier (1966) and Ostermeier (1967); in Reinard (1984, Experiment 1) and in Reinard and Reynolds (1976), recorded here under the former; in Sikkink (1954) and Sikkink (1956); and in Whitehead (1969) and Whitehead (1971).

Analysis

The unit of analysis was the message pair (that is, the pair composed of an explicit message and its inexplicit counterpart). When the same messages were used in more than one investigation, results were combined. Such combined results were computed in the following cases: results recorded under Cathcart (1953, 1955) reflect results from Cathcart (1953, 1955) and from Bostrom and Tucker (1969); results recorded under “McCroskey capital punishment” reflect results from studies 1, 3, and 4 in McCroskey (1967b); results recorded under “McCroskey pro-education” reflect results from studies 1, 4, and 5 in McCroskey (1967b) and McCroskey (1970).[i] Some designs used multiple messages but did not report results separately, and so were treated as having only one message (Berger 1988, second preliminary study and main study; Whitehead 1969, 1971); the consequence is that the present analysis underrepresents any message-to-message variability in these data.

The individual correlations (effect sizes) were initially transformed to Fisher’s zs; the zs were analyzed using random-effects procedures described by Shadish and Haddock (1994), with results then transformed back to r. A random-effects analysis was employed in preference to a fixed-effects analysis because of an interest in generalizing across messages.

Meta-analysts of message effects research face a circumstance parallel to that of primary researchers whose designs contain multiple instantiations of message categories. Such multiple-message designs can be analyzed treating messages either as a fixed effect or as a random effect. The relevant general principle is that replications should be treated as random when the underlying interest is in generalization. This reflects the fact that fixed-effects and random-effects analyses test different hypotheses: a fixed-effects analysis tests a hypothesis concerning whether the responses to a fixed, concrete group of messages differ from the responses to some other fixed, concrete group of messages, whereas a random-effects analysis tests whether responses to one category of messages differ from responses to another category of messages (see, e.g., Jackson 1992: 110). A meta-analysis involves a collection of replications (parallel to the message replications in a multiple-message primary research design), and similar considerations (including whether the analyst is interested in generalization) bear on the choice between a fixed and a random-effects meta-analysis (for some discussion, see Jackson 1992: 123; Shadish & Haddock 1994). In the present review, the interest is naturally not in the concrete messages studied by past investigators, but in the larger classes of messages of which the studied messages are instantiations; hence a random-effects analysis was the appropriate choice. In a random-effects analysis, the confidence interval around an obtained mean effect size reflects not only the usual human-sampling variation, but also between-studies variance; this has the effect of widening the confidence interval over what it would have been in a fixed-effects analysis (see Shadish & Haddock 1994: 275).

3. Results

Persuasion Effects

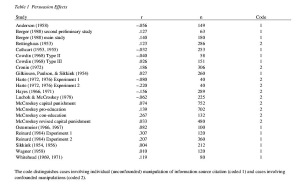

Details for each included case appear in Table 1. Effect sizes were available for 23 cases with a total of 5,358 participants. Across all 23 cases, the mean correlation was .064 [Q(22) = 60.2, p<.001]; the 95% confidence interval for this mean was .014, .114, indicating a significant persuasive advantage for messages providing information-source citations.

There were 13 cases (N = 2,106) involving the individual manipulation of information-source citation. Across these cases, the mean correlation was .073 [Q(12) = 23.1, p<.05]; the 95% confidence interval was .018, .128

.

There were 10 cases (N = 3,252) involving the joint manipulation of information-source citation and another message feature. Across these cases, the mean correlation was .050 [Q(9) = 37.1, p<.001]; the 95% confidence interval was -.043, .144.

Credibility Effects

Details for each included case appear in Table 2. Effect sizes were available for 10 cases with a total of 2,601 participants. Across all 10 cases, the mean correlation was .077 [Q(9) = 81.0, p<.001]; the 95% confidence interval was -.053, .206.

There were 4 cases (N = 553) involving the individual manipulation of information-source citation. Across these cases, the mean correlation was .169 [Q(3) = 10.9, p<.05]; the 95% confidence interval was .028, .311.

There were 6 cases (N = 2,048) involving the joint manipulation of information-source citation and another message feature. Across these cases, the mean correlation was .009 [Q(5) = 69.1, p<.001]; the 95% confidence interval was -.170, .188.

4. Discussion

General Effects

Characterized very broadly, these results suggest that advocates have little to fear from explicitly identifying their information sources. For studies individually manipulating information-source citation, messages with more explicit argumentative support are significantly more credible and significantly more persuasive than their less explicit counterparts.

An Implicit Limiting Condition

One might plausibly suppose that the effects (on persuasiveness and credibility) of identifying one’s information sources will depend in part on the nature of those sources. Two advocates who are equally explicit about their supporting sources might find different effects if one advocate’s sources are plainly well-qualified and trustworthy where the other’s are not.

The extant research literature does not provide extensive evidence that bears on this supposition, but two points can appropriately be made. First, in the great bulk of the research reviewed here, the sources identified in the more-explicit messages were ones likely to have been perceived as relatively high in credibility. In some cases, investigators pretested possible sources before constructing their experimental materials; for example, Bettinghaus (1953) used information sources identified in pretesting as persons thought competent to render judgments in the topic area. Investigators have commonly not intentionally sought to invoke palpably weak information sources. Thus there may implicitly be a limiting condition on the observed general effects, specifically, that persuasion-and credibility-enhancing effects of explicit source identification obtain only when the identified sources are of sufficiently high quality.

Second, the few studies that have varied the apparent quality of the identified sources have not produced consistent effects. Luchok and McCroskey’s (1978) results suggested that citing poor-quality information sources would inhibit persuasion (compared to not providing source citations); however, in Cronin’s (1972) study, citing low-credibility information sources was more persuasive than not citing any information sources.[ii]

At a minimum, then, one may say that the observed positive effects on credibility and persuasiveness obtain at least when the identified sources are recognizably sound. It is not yet clear whether there are specifiable general circumstances under which such positive effects might obtain with poorer information sources. Future research might usefully be directed at clarifying this potential limiting condition

Individual and Joint Effects

The best evidence for the effect of a given message variation obtains in designs in which that variation is manipulated independently of other message variations. In this research area, however, a number of studies have jointly manipulated information- source citation and other message properties (commonly capturing such joint variation under the general heading of “evidence”). Such designs, of course, obscure the possible causal mechanisms for any observed effects. In the research reviewed here, the observed mean effects (on credibility and persuasion) of such joint-manipulation designs are not dependably different from those of individual-manipulation designs, though the joint-manipulation mean is smaller and (unlike the individual-manipulation mean) is not dependably different from zero. Thus with respect to the research question of interest here – that is, the question of the effects of variation in information-source citation – the best evidence in hand (the evidence from individual-manipulation studies) indicates that both persuasiveness and credibility are significantly enhanced by information-source citation.

But these findings also speak to the research practice of jointly manipulating several message variables in this confounded way. Such quasi-experimental designs can be attractive for various reasons. In the early stages of research, uncertainty about possible mechanisms might recommend casting one’s net widely. For field (as opposed to laboratory) experiments, quasi-experimental designs may be more practical (e.g., Gonzales, Aronson, & Costanzo 1988; Reynolds, West, & Aiken 1990). More generally, manipulating a suite of message features can appear to promise stronger effects: one might expect relatively larger impact by contrasting two messages that vary in several features (for instance, comparing a message that lacks both quantitative specificity and information- source citations against a parallel message that is both quantitatively more explicit and provides citations to the sources of its information) rather than just one feature. Interestingly enough, however, in the limited data afforded by this research area, there is no evidence of such enhanced impact. This concretely illustrates that the effects of joint manipulations are not necessarily the sum of the effects expected from the individual manipulations, and indeed may not be larger than the effect of a single manipulation. Insofar as experimental design in persuasion effects research is concerned, then, the lesson is that the manipulation of a suite of message features does not necessarily enhance effect size.

Explaining the Observed Effects

Credibility enhancement. One appealing possible explanation of the observed effects is that explicit identification of information sources enhances the communicator’s credibility, which then leads to enhanced persuasion. Such a process would presumably involve receivers’ invoking a credibility heuristic, in which the apparent credibility of the communicator is used as a basis for assessing the advocated view (see, e.g., Chaiken 1987; Petty & Cacioppo 1986).

This explanation leads to the expectation that communicators initially low in credibility might enjoy greater impact from explicit source identification than would high-credibility communicators. High-credibility communicators might not enjoy so much credibility enhancement from explicitly identifying their sources as would low-credibility communicators (because of ceiling effects), and so they might not obtain so much greater persuasive impact.

Evidence relevant to this expectation can potentially be obtained from research designs varying both initial communicator credibility and information-source identification. A number of studies have used designs of this sort, though commonly these do not provide sufficient quantitative information to permit useful meta-analytic treatment; however, it is possible to consider simply the direction of effect observed in such studies. As a broad overview, it appears that there is not a striking difference between highand low-credibility communicators in the character of the observed effects of information-source-citation variations on either persuasive outcomes or perceived credibility.

With respect to persuasive effects, for communicators initially high in credibility, a number of studies have indicated that messages citing information sources have some persuasive advantage over those without such citations (Harte 1972, Experiment 1; McCroskey capital punishment; McCroskey pro-education; McCroskey revised capital punishment; McCroskey revised education), but several studies have reported effects in directions favoring messages without citations (Harte 1972, Experiment 2; Hayes 1966; Luchok & McCroskey 1978; McCroskey con-education). Similarly, for communicators initially low in credibility, in several cases messages with explicit citations have been more persuasive than their nonexplicit counterparts (Luchok & McCroskey 1978; McCroskey capital punishment; McCroskey pro-education; McCroskey revised capital punishment; McCroskey revised education), but in a number of cases the opposite direction of effect has been observed (Harte 1972, Experiment 1; Harte 1972, Experiment 2; Hayes 1966; McCroskey con-education). That is, the pattern of effects does not display the expected greater superiority of information-source citation for low-credibility communicators.

Concerning credibility perceptions, for communicators initially high in credibility, a number of studies have indicated that messages with information-source citations lead to more positive credibility judgments than do messages without such citations (Fleshler, Ilardo, & Demoretcky 1974; McCroskey pro-education; McCroskey con-education; McCroskey revised education), but several other studies have reported mixed effects or effects favoring messages without explicit citations (Harte 1972, Experiment 1; Harte, 1972 Experiment 2; Hayes 1966; McCroskey capital punishment). Similarly, for communicators initially low in credibility, some studies report that messages with information-source citations enhance perceived credibility more than do messages without such citations (Fleshler, Ilardo, & Demoretcky 1974; Hayes 1966; McCroskey pro-education; McCroskey con-education; McCroskey revised education), but other cases favor messages without such citations or report mixed directions of effect (Harte 1972, Experiment 1; Harte 1972, Experiment 2; McCroskey capital punishment). Again, the pattern of effects does not suggest that low-credibility communicators enjoy some marked advantage over high-credibility communicators in the impact of information-source citations on credibility perceptions.

Thus variations in information-source citation do not seem to have dramatically different effects on the perceived credibility of, or the persuasiveness of, communicators initially high in credibility and those initially low. This research evidence is limited in a number of important ways (there are few relevant cases, effect sizes are not available, and nearly all the studies involve confounded designs), so one ought not make too much of what is in hand; future research could plainly be useful in clarifying the relevant relationships. But at a minimum the evidence to date does not give substantial encouragement to the supposition that the effects of information-source-citation variations depend in some crucial way on the communicator’s initial level of credibility. This, in turn, suggests that credibility enhancement may not be the causal mechanism by which information-source citation enhances persuasion.

Argument enhancement. An alternative possible account is that information-source citation directly enhances belief in the relevant supporting argument, thereby making the message more persuasive. That is, quite apart from any effects that such citation might have on perceptions of the communicator’s credibility, explicit source identification could enhance the persuasiveness of the supporting argumentation. For instance, a receiver might reason that a particular supporting argument is more likely to merit belief given the identification of the source of some information invoked by the argument. Thus the impact of the supporting argument might itself directly be enhanced by such explicitness, without any intervening step involving enhanced perceptions of the communicator’s credibility. From this vantage point, the observed credibility-enhancement effect of information-source citation is epiphenomenal, that is, not implicated in bringing about the observed effects on persuasiveness.

This explanation underscores the importance of research focussed on identification of specific argument features that enhance the impact of individual arguments (and thus the impact of the messages in which they appear). One well-known body of research that might appear to bear on this question is elaboration likelihood model research concerning the role that variation in “argument strength” plays in persuasion (e.g., Petty, Cacioppo, & Goldman 1981). But as several commentators have noted (e.g., Areni & Lutz 1988), this research has not specified the properties that make specific arguments relatively more or less persuasive. The present results suggest that information-source citation might be a candidate worthy of closer examination.

But there are at least two different means by which information-source citation could directly bolster the persuasiveness of supporting arguments. One possibility is that the effect arises through the receiver’s careful scrutiny of the source-identification material; if this is the underlying process, then identification of low-credibility sources might diminish persuasiveness (because the receiver’s close examination of the explicit identification material will reveal the source’s weaknesses). A second possibility is a more heuristic-like process, in which the mention of an information source is taken as a sign of the merit of the argument, in a way that does not necessarily involve careful attention to the argumentative details; if this is the underlying process, then even identification of low-credibility information sources might enhance persuasiveness (that is, citing any information source may be taken as an indication of the argument’s being worthy of belief).[iii]

5. Conclusion

Messages with more explicit identification of their information sources are significantly more credible and significantly more persuasive than their less explicit counterparts. Additional research will be needed to identify the limits of the observed effects (circumstances under which the effects do not occur, or are reversed) and to explain how and why the effects arise. But as a rule, advocates can appropriately be advised, on both normative and instrumental grounds, to explicitly articulate their argumentative support in this way.

NOTES

[i] The results recorded under McCroskey con-education are from McCroskey (1970); the results recorded under McCroskey revised capital punishment are from McCroskey (1967b, Study 5).

[ii] Warren’s (1969) design varied the credibility of information sources, and Dresser’s (1962, 1963) design varied both the credibility of information sources and the relevance of the provided material to the claims advanced; neither, however, contained a no-source-citation condition, and thus these studies could not provide evidence about the relative persuasiveness of leaving information sources uncited versus citing low-credibility sources.

[iii] Thanks to Sally Jackson for suggesting this possibility

REFERENCES

Anderson, D. (1958). The effect of various uses of authoritative testimony in persuasive speaking (Master’s thesis, Ohio State University, 1958).

Areni, C. S., & Lutz, R. J. (1988). The role of argument quality in the elaboration likelihood model. In: M. J. Houston (Ed.), Ad-vances in Consumer Research (Vol. 15, pp. 197-203). Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research.

Babich, R. M. (1971). Perceived informativeness related to attitude change in topic, evidence, and source variant messages (Doctoral dissertation, University of Colorado, 1971). Dissertation Abstracts International 32 (1972), 4147A. (University Microfilms No. AAG-723621).

Berger, K. A. (1988). The effect of report, inference, and judgment messages in the absence and presence of a source on attitudes and beliefs (Doctoral dissertation, New York University, 1988). Dissertation Abstracts International 49 (1988), 1205A. (University Microfilms No. AAG-8814669).

Bettinghaus, E. P., Jr. (1953). The relative effect of the use of testimony in a persuasive speech upon the attitudes of listeners (Master’s thesis, Bradley University, 1953).

Bostrom, R. N., & Tucker, R. K. (1969). Evidence, personality, and attitude change. Speech Monographs 35, 22-27.

Cathcart, R. S. (1953). An experimental study of the relative effectiveness of selected means of handling evidence in speeches of advocacy (Doctoral dissertation, Northwestern University, 1953). Dissertation Abstracts 14 (1954), 416. (University Microfilms No. AAG-0007021).

Cathcart, R. S. (1955). An experimental study of the relative effectiveness of four methods of presenting evidence. Speech Monographs 22, 227-233.

Chaiken, S. (1987). The heuristic model of persuasion. In: M. P. Zanna, J. M. Olson, & C. P. Herman (Eds.), Social Influence: The Ontario Symposium, Vol. 5 (pp. 3-39). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Cowdin, H. P. (1968). Development of persuasive messages based on the belief patterns of the audience, and the effects of authorities and dogmatism on change of beliefs (Doctoral dissertation, University of Iowa, 1968). Dissertation Abstracts 29 (1968), 1858A. (University Microfilms No. AAG-6816793).

Cronin, M. W. (1972). An experimental study of the effects of authoritative testimony on small-group problem-solving discussions (Doctoral dissertation, Wayne State University, 1972). Dissertation Abstracts International 33 (1973), 6485A. (University Microfilms No. AAG-7312497).

Dresser, W. R. (1963). Effects of “satisfactory” and “unsatisfactory” evidence in a speech of advocacy. Speech Monographs 30, 302-306.

Van Eemeren, F. H., Grootendorst, R., Jackson, S., & Jacobs, S. (1993). Reconstructing Argumentative Discourse. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press.

Fleshler, H., Ilardo, J., & Demoretcky, J. (1974). The influence of field dependence, speaker credibility set, and message documentation on evaluations of speaker and message credibility. Southern Speech Communication Journal 39, 389-402.

Gilkinson, H., Paulson, S. F., & Sikkink, D. E. (1954). Effects of order and authority in an argumentative speech. Quarterly Journal of Speech 40, 183-192.

Gonzales, M. H., Aronson, E., & Costanzo, M. A. (1988). Using social cognition and persuasion to promote energy conservation: A quasi-experiment. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 18, 1049-1066.

Harte, T. B. (1972). The effects of initial attitude and evidence in persuasive communication (Doctoral dissertation, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 1972). Dissertation Abstracts International 34 (1973), 890A. (University Microfilms No. AAG-7317234).

Harte, T. B. (1976). The effects of evidence in persuasive communication. Central States Speech Journal 27, 42-46.

Hayes, H. B. (1966). Source credibility and documentation as factors of persuasion in international propaganda (Doctoral dissertation, University of Iowa, 1966). Dissertation Abstracts 27 (1966), 450A. (University Microfilms No. AAG-6607209).

Hayes, H. B. (1971). International persuasion variables are tested across three cultures. Journalism Quarterly 48, 714-723.

Holtzman, P. D. (1966). Confirmation of ethos as a confounding element in communication research. Speech Monographs 33, 464-466.

Hovland, C. I., & Mandell, W. (1952). An experimental comparison of conclusion-drawing by the communicator and by the audience. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 47, 581-588.

Jackson, S. (1992). Message Effects Research: Principles of Design and Analysis. New York: Guilford Press.

Jackson, S., & Jacobs, S. (1980). Structure of conversational argument: Pragmatic bases for the enthymeme. Quarterly Journal of Speech 66, 251-265.

Johnson, B. T. (1989). DSTAT: Software for the Meta-Analytic Review of Research Literatures. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Kardes, F. R. (1988). Spontaneous inference processes in advertising: The effects of conclusion omission and involvement on persuasion. Journal of Consumer Research 15, 225-233.

Kellermann, K. (1980). The concept of evidence: A critical review. Journal of the American Forensic Association 16, 159-172.

Kilcrease, P. P. (1977). An experimental investigation of Fishbein and Ajzen’s model of behavioral prediction, their principles of change, and the effect of the use of evidence in a persuasive communication (Doctoral dissertation, Louisiana State University, 1977). Dissertation Abstracts International, 38 (1978), 3803A-3804A. (University Microfilms No. AAG-7728684).

Luchok, J. A. (1973). The effect of evidence quality on attitude change, credibility, and homophily. Unpublished master’s thesis, West Virginia University.

Luchok, J. A., & McCroskey, J. C. (1978). The effect of quality of evidence on attitude change and source credibility. Southern Speech Communication Journal 43, 371-383.

McCroskey, J. C. (1966). Experimental studies of the effects of ethos and evidence in persuasive communication (Doctoral dissertation, Pennsylvania State University, 1966). Dissertation Abstracts 27 (1967), 3630A. (University Microfilms No. AAG-6705945).

McCroskey, J. C. (1967a). The effects of evidence in persuasive communication. Western Speech 31, 189-199.

McCroskey, J. C. (1967b). Studies of the effects of evidence in persuasive communication. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Speech Communication Research Laboratory, report SCRL 4-67.

McCroskey, J. C. (1969). A summary of experimental research on the effects of evidence in persuasive communication. Quarterly Journal of Speech 55, 169-176.

McCroskey, J. C. (1970). The effects of evidence as an inhibitor of counter-persuasion. Speech Monographs 37, 188-194.

McCroskey, J. C., & Dunham, R. E. (1966). Ethos: A confounding element in communication research. Speech Monographs 33, 456-463.

O’Keefe, D. J. (1997). Standpoint explicitness and persuasive effect: A meta-analytic review of the effects of varying conclusion articulation in persuasive messages. Argumentation and Advocacy 34, 1-12.

Ostermeier, T. H. (1966). An experimental study on the type and frequency of reference as used by an unfamiliar source in a message and its effect upon perceived credibility and attitude change (Doctoral dissertation, Michigan State University, 1966). Dissertation Abstracts 27 (1967), 2216A. (University Microfilms No. AAG-6614159).

Ostermeier, T. H. (1967). Effects of type and frequency of reference upon perceived source credibility and attitude change. Speech Monographs 34, 137-144.

Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). Communication and Persuasion: Central and Peripheral Routes to Attitude Change. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Petty, R. E., Cacioppo, J. T., & Goldman, R. (1981). Personal involvement as a determinant of argument-based persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 41, 847-855.

Reinard, J. C. (1984). The role of Toulmin’s categories of message development in persuasive communication: Two experimental studies on attitude change. Journal of the American Forensic Association 20, 206-223.

Reinard, J. C. (1988). The empirical study of the persuasive effects of evidence: The status after fifty years of research. Human Communication Research 15, 3-59.

Reinard, J. C. (1994). The persuasive effects of assertive evidence. In: M. Allen & R. W. Preiss (Eds.), Prospects and Precautions in the Use of Meta-Analysis (pp. 127-157). Dubuque, IA: Brown and Benchmark.

Reinard, J. C., & Reynolds, R. A. (1976, November). An experimental study of the effects of Toulmin’s pattern for argument development on attitude change. Paper presented at the meeting of the Western Speech Communication Association, San Francisco, CA. (ERIC document number ED133782).

Reynolds, K. D., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (1990). Increasing the use of mammography: A pilot program. Health Education Quarterly 17, 429-441.

Rosenthal, R. (1991). Meta-Analytic Procedures for Social Research (rev. ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Shadish, W. R., & Haddock, C. K. (1994). Combining estimates of effect size. In: H. Cooper & L. V. Hedges (Eds.), Handbook of Research Synthesis (pp. 261-281). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Sikkink, D. E. (1954). An experimental study of the effects on the listener of anti-climax order and authority in an argumentative speech (Doctoral dissertation, University of Minnesota, 1954). Dissertation Abstracts 14 (1954), 2157. (University Microfilms No. AAG-0009622).

Sikkink, D. E. (1956). An experimental study of the effects on the listener of anticlimax order and authority in an argumentative speech. Southern Speech Journal 22, 73-78.

Wagner, G. A. (1958). An experimental study of the relative effectiveness of varying amounts of evidence in a persuasive communication (Master’s thesis, Mississippi Southern College, 1958).

Warren, I. D. (1969). The effect of credibility in sources of testimony on audience attitudes toward speaker and message. Speech Monographs 36, 456-458.

Whitehead, J. L., Jr. (1969). An experimental study of the effects of authority-based assertion (Doctoral dissertation, Indiana University, 1969). Dissertation Abstracts International 30 (1970), 5101A-5102A. (University Microfilms No. AAG-7007518).

Whitehead, J. L., Jr. (1971). Effects of authority-based assertion on attitude and credibility. Speech Monographs 38, 311-315.