ISSA Proceedings 1998 – Greek Mythic Conceptions Of Persuasion

In his provocative work, Protagoras and Logos, Edward Schiappa (1991) suggests that the Presocratics, the Sophists and Plato shared a different approach to language and communication. Still constrained to varying degrees by their primarily oral culture, they nevertheless offered prose as an alternative to poetry, and “treated language itself as an object of analysis for the first time in Greek history” (31). While Schiappa treats the definition and historical manifestations of logos with great care, he fails to do the same with mythos; presumably the Presocratics, the Sophists and Plato offered an alternative not only to “poetry as a vehicle of wisdom and entertainment,” but also to mythic accounts and conceptions of persuasion (31). Hence it is possible to better understand the contributions of early theorists of logos by better understanding the mythic understanding of persuasion that was available to the Greeks. In this essay I will explore the Greek mythic beliefs that persuasion took place through the action of the deities Hermes, Peitho, and the Charites (Barthell 1971: 152). After considering the range of meanings that each represents, I will consider the meanings represented by various combinations of them. In pursuing these meanings, I’m attempting to understand what a Greek, especially an Athenian, would gain by asking, “How can I persuade x?” and receiving the answer, “By considering Peitho, the Charites, and Hermes.” This question would have acquired more urgency around 500 BC, after Kleisthenes’ reforms, when the Athenian Pnyx was reinforced and dressed for the first time, hence dominating the approach to the marketplace (Kournouniotes and Thompson 1932: 216). After considering likely answers to the question, I will return to Schiappa’s argument, and maintain that Protagoras and later theorists where not as revolutionary as Schiappa portrays them, when one treats the mythic-poetic tradition as more than a preference for poetry.

In his provocative work, Protagoras and Logos, Edward Schiappa (1991) suggests that the Presocratics, the Sophists and Plato shared a different approach to language and communication. Still constrained to varying degrees by their primarily oral culture, they nevertheless offered prose as an alternative to poetry, and “treated language itself as an object of analysis for the first time in Greek history” (31). While Schiappa treats the definition and historical manifestations of logos with great care, he fails to do the same with mythos; presumably the Presocratics, the Sophists and Plato offered an alternative not only to “poetry as a vehicle of wisdom and entertainment,” but also to mythic accounts and conceptions of persuasion (31). Hence it is possible to better understand the contributions of early theorists of logos by better understanding the mythic understanding of persuasion that was available to the Greeks. In this essay I will explore the Greek mythic beliefs that persuasion took place through the action of the deities Hermes, Peitho, and the Charites (Barthell 1971: 152). After considering the range of meanings that each represents, I will consider the meanings represented by various combinations of them. In pursuing these meanings, I’m attempting to understand what a Greek, especially an Athenian, would gain by asking, “How can I persuade x?” and receiving the answer, “By considering Peitho, the Charites, and Hermes.” This question would have acquired more urgency around 500 BC, after Kleisthenes’ reforms, when the Athenian Pnyx was reinforced and dressed for the first time, hence dominating the approach to the marketplace (Kournouniotes and Thompson 1932: 216). After considering likely answers to the question, I will return to Schiappa’s argument, and maintain that Protagoras and later theorists where not as revolutionary as Schiappa portrays them, when one treats the mythic-poetic tradition as more than a preference for poetry.

In the discussions of deities that follows, it would be well to keep in mind the following chronology. The Iliad and the Odyssey date from the eighth century BC; Hesiod’s poems date from the seventh century BC; and the Homeric Hymns date from the sixth and fifth centuries BC. The Homeric Hymn to Hermes is from the sixth, probably late sixth century BC. Protagoras arrived in Athens around 450 BC.

1. Analysis of deities associated with persuasion

1.1 Hermes

Hermes probably originally arose as a god of the stone heaps that marked property boundaries (Farnell 1909: 7; Brown 1917/1990: 32). Hermes was the power found in the heap (Burkert 156). Because many tribal activities took place at the boundary between tribal territories, Hermes took on a range of associated meanings. Trading took place at the boundaries, so Hermes became a god of the marketplace, which later moved into the center of towns (Brown 1917/1990: 37). At first the stone heaps marked a neutral and sacred spot where trading could be safely conducted by traveling tradesmen and tribal groups with surplus goods (Farnell 1909: 26). Later, trading could safely be conducted in towns themselves. For example, in archaic Athens, the marketplace was on the northwest slope of the Acropolis, but was moved further north by Solon to a more central, level location (Travlos 1971: 2). At the symbolic center of the new agora was the altar of the Twelve Gods, and a Stoa of large herms (21). From that center, beginning around 520 BC, distances were measured and marked with herms at halfway points along all the major roads leading to the city (Brown 1917/1990: 107). The herms were inscribed with a statement of ownership by the tyrant Hipparchus, and a maxim such as “Think just thoughts as you journey” (Brown 1917/1990: 111; Parker 1996: 80). In this aspect Hermes implies that persuasion was a key to the success of the marketplace.

Farnell (1909) was worried over the dual associations of Hermes with the marketplace and thieving. He resolved this contradiction by arguing it does not mean that the state would pray to Hermes when it was about to represent itself dishonestly, nor that the state tolerated dishonest trading, but that “he stood to preserve the public peace of the place,” since early assemblies and deliberations were held there ( 24, 27). Especially the use of Herms, inscribed with the names of public benefactors, serving as mileage markers near the end of the sixth century BC, “may have spread the belief that the god was interested in the general welfare of the city” (26). Brown (1917/1990) sought to preserve the contradiction because he believed it indicated social tensions in Athens. In the Homeric Hymn, Hermes’ desires and characteristics are those of the “merchant and the craftsman” working in the Agora (81). Hence the hymn celebrates the increasing commercialization of the agora and ridicules aristocratic disdain for the nouveau riche (82).

Wife abductions and livestock raids took place at the boundary, so Hermes became a god of marriage, seduction and stealthy thievery (Brown 1917/1990: 42; Kerenyi 1944/1976): 60). As a god of seduction, he was mainly a god devoted to fertility and increase (Farnell V 25). The phallus on herms was probably originally a fertility symbol to those herding at the boundary. Yet, as Parker (1996) notes, “It then got stuck; for herms soon entered the city as images to which cult was paid, but retained the gross appendage” (82). Hermes’ ithyphallic nature remained important as it then began to symbolize the growth and continuation of the city. Hence even the later mutilation of the herms provoked widespread shock and panic.

Hermes’ connection to thievery was recognized in common outcry at the beginning of a new undertaking – “Koinos Hermes,” “a theft done together” (Kerenyi 1944/1976: 60). Hermes’ thefts, both in Homer and the Homeric Hymn to Hermes, are aided by trickery such as mists, sleep induced by his wand or staff, or invisibility (Brown 1917/1990: 11). This aspect of Hermes, when applied to persuasion, connotes the use of persuasion to mislead.

Negotiations between tribes occurred at the boundary, so Hermes became a god of intergroup negotiation and cunning speech (Brown 1917/1990: 8). By Homer’s time heralds had gained some of Hermes’ sanctity, and presently adopted Hermes’ shepherd’s staff, the kerykeion: “hence he became specially their tutelary divinity and the guardian of such morality as attached to Hellenic diplomacy” (Farnell 1909: 20). For example, records of some sacrifices note that the tongue of the victim was reserved for Hermes and the heralds (30n.). A further link between Hermes and heralds is found in the Greek term for interpreter, hermeneus, which derives from hermes (Burkert 1985: 158). Hence Hermes as a god of persuasion would suggest ambassadors’ speeches, which are portrayed as early as the Iliad (Wooten 1973: 209).

More broadly than these state functions, Hermes was associated with all cunning speech. In the Odyssey, Odysseus is related to Hermes on his mother’s side (Kerenyi 1944/1976: 48). Odysseus’ grandfather Autolycos, a son of Hermes, is highlighted for his prowess in thieving and manipulating oaths (Burkert 1985: 158). In the Homeric Hymn to Hermes, there is an example of such an oath when Apollo brings Hermes before Zeus after accusing Hermes of stealing Apollo’s cattle. Hermes swears not that he did not steal the cattle, but that he never drove the cattle to his house, and never stepped across his threshold. This sounds like a denial until one remembers that Hermes had driven the cattle to a cave and had entered his house through the keyhole. Like his connection to thievery, Hermes’ connection to cunning speech suggests the use of persuasion to mislead. The connection to cunning speech also suggests a certain indirect style of speaking that may be useful in persuasion.

Finally, people traveled at the boundaries, and often delighted in finding and consuming offerings to Hermes at the base of the stone heaps. So, Hermes became a companion god of travelers, and a god of sudden windfalls and the propitious discovery of good things (Brown 1917/1990: 20, 44; Kerenyi 1944/1976: 58-59). Yet Hermes was not credited with all lucky events. If a mentally deficient person had good luck, it was attributed to Herakles (Kerenyi 1944/1976: 60). Not only did he accompany traders on their travels of discovery, but Hermes also was credited mythologically with inventing several useful items. For example, the Homeric Hymn to Hermes credits him with inventing the tortoise shell lyre, reed pipes, and starting a blaze using fire sticks. Further, Hermes could lend grace and ingenuity to human artists’ crafts (Grantz 1993: 109). With regard to persuasion, these qualities suggest the process that would later be called invention.

Through analogical extension, Hermes became associated with other types of boundaries. One was the boundary between sleeping and waking. Farnell (1909) notes that “From the Homeric period onwards we have evidence proving the custom of offering libations to Hermes after the evening banquet, before retiring to rest; and we may believe such offerings aimed at securing happy sleep and freedom from ghostly terrors” (14). During Protagoras’ time in Athens, near the end of the fifth century BC, Hermes became explicitly associated with the new cult of Asclepias, the oracular physician, as the “bringer of dreams” (Parker 1996: 182). Yet Hermes’ association with omens had begun earlier. In the Homeric Hymn, Zeus gives to Hermes power over birds of omen (Gantz 1993: 106). In addition, Hermes was a patron of “divination by counters” (Farnell 1909: 17). Hence Hermes was implicated with ideas about the future.

Another analogical boundary associated with Hermes was that between the living and the dead. Farnell (1909) related that “On the Acropolis in the temple of Athena Polias, stood a very ancient wooden agalma of Hermes, said to have been dedicated by Kekrops, and as its form was almost invisible beneath the myrtle boughs wrapped around it, we may regard it as descending from the semi-iconic period” (5). Harrison (1966) believed Hermes was represented there as a snake, an unmistakable Greek chthonic symbol (295). In the Odyssey, dating from the same period as the temple, Hermes first appears in myth as a conductor of souls, when he awakens the souls of the slain suitors and safely guides them to Hades (Gantz 1993: 108). In addition, Hermes was commonly addressed as the agent of “binding” in written curses buried with the hope that Hermes would conduct the person named to Hades (Guthrie 1950: 271). In connection with persuasion this function most strongly suggests the possibility of using persuasion to gain revenge, especially through what would later be called forensic speaking.

The last boundary associated with Hermes was the boundary between public and private. Frequently at Greek house gates and temple entrances, herms were placed both to guard the emerging members of the household and to help keep daimons from entering the house (Farnell 1909: 18). As in the marketplace, Hermes served a protective at the house. Hence he might travel with citizens as they hurried to the market or the assembly.

Inconsistencies in Hermes’ family history provide clues to additional meanings. According to the Odyssey, and Hesiod’s Theogony, Hermes was the daughter of Zeus and Maia, the daughter of Atlas (Gantz 1993: 105-06). While Hermes emerges in epic and lyric poetry as the father of children by Polymele, Philonis, Aphrodite, and an unnamed daughter of Dryops, in the later Homeric Hymn to Hermes, Hermes claims Apollo’s place as consort to Mnemosyne, Memory, mother of the Muses. If Brown (1917/1990) is correct that the hymn was composed in the court of Hipparchus (c. 514 BC), frequented by the poet Simonides, then Hermes as a god of persuasion suggested the art of memory as well (92, 124, 130). Simonides, both in legend and in a c.264 public inscription, is named as the inventor of an art of memorization (Yates 1966: 28 ).

Finally, worship of Hermes was widespread, but not institutionalized. Rather, references to poorly understood “Hermaia” festivals were found throughout Greece (Farnell 1909: 31). There is reliable evidence that the third day of the Anthesteria festival was dedicated to sacrifices to Hermes as the escorter of souls (Simon 1983: 93). There may have been an archaic altar to Hermes in the Akademia neighborhood Travlos 1971: 42). Sacrifice of goats, Hermes’ sacrificial creature, was the second most common type of sacrifice (Burkert 1985: 54).Yet, again, the vast majority of these sacrifices were part of private ceremonies rather than public events. In all, he was rarely mentioned in the family trees of prominent clans or towns, and artistic representations of Hermes used in public worship are rare (Farnell 1909: 1, 32).

However, in the first half of the fifth century, sculptors “idealized and enobled” full-figure representations of Hermes, and representations of all types became more widespread (Farnell 1909: 55). Specifically, Hermes began to get younger and more athletic. Previously, almost all representations of Hermes were of a bearded, older man. Also, after Hipparchus set up the first Athenian herms, “the city was soon flooded with them. By the late fifth century the doorstep herm, that cheerfully shameless figure, must have been the most familiar divine presence in the streets of Athens” (Parker 1996: 81). It is tempting to connect these developments with the increasing importance of persuasion in Greek life.

1.2 Peitho

Peitho literally means “persuasion.” Since there were no clear capitalization patterns in archaic or classical Greek, there was no clear distinction between Peitho the goddess and peitho the abstract concept (Buxton 1982: 30). In addition, she seems to have operated simultaneously as a goddess of private and public persuasion. According to Buxton (1982), “to Greeks all Peitho was ‘seductive’. Peitho is a continuum within which divine, secular, erotic and non-erotic come together” (31).

The earliest poetic sources stress her erotic nature. In Hesiod’s Works and Days, Peitho gives Pandora golden necklaces to wear (69). According to Buxton (1982), “These were traditional instruments of erotic enticement” (37). Sappho portrays Peitho as a handmaiden of Aphrodite who can convince the object of her desires to love, and who can also “cheat mortals” when love turns out to be impermanent (38, 65).

Later cults and visual portrayals linked Peitho with marriage, which had a dual nature as a sexual relationship and an institution important to the state (Shapiro 1993: 187-88). In representations on vases predating Protagoras’ arrival in Athens, Peitho is portrayed playing a part in events of the Trojan War. She is either rewarding Paris for choosing Aphrodite, or coaxing a reluctant Helen to marry (Shapiro 1993: 189-91). Again, these private events had tremendous political implications. Buxton (1982) has argued that Peitho was often linked with other personifications with such a dual role:

“the characteristics of Eunomia, Euklia and Harmonia, like the characteristics of Peitho, span the erotic and public spheres. Seductiveness resides not only in Persuasion, but in Good Order, Noble Reputation, and Harmony” (48). In association with these other deities, Peitho may have suggested ethos and what would later be called arrangement.

At Athens, Peitho was at first linked in cult with Aphrodite Pandemos. Both shared a temple on the south or southwest slope of the Acropolis. Although inscriptions linked with the cult are late, they state that the cult was ancient. Again, there is confusion over Peitho’s nature, since Plato defined “Pandemos” as the vulgar sphere of Aphrodite’s activity (Farnell 1896: 660). Yet there is no evidence that Plato’s definition was shared, and it certainly did not exist before the fifth century BC. Rather, Apollodoros’ interpretation that the temple was built close to the old marketplace and so named because “all the people” gathered and deliberated there seems more correct (Buxton 1982: 34; Parker 1996: 49). As Farnell (1896) put it, “What we know is that until the declining period of Greek history, the cult of Aphrodite, so far as it appears in written or monumental record, was as pure and austere as that of Zeus and Athena, purer than that of Artemis, in nearly all Greek communities rules of chastity being sometimes imposed upon her priestesses . . . “ ( 663). Both Aphrodite Pandemos and Peitho were honored in a festival called the Aphrodisia; after “the sanctuary was purified with the blood of a dove, the altars were anointed, and the cult images conducted in procession to the place where they were washed” (Simon 1983: 48-49). In connection with Aphrodite Pandemos, then, Peitho connoted ties binding the citizens of the polis together.

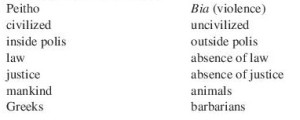

In poetry, tragedy, and sophistic speeches, the nature of peitho was continually elaborated beginning ten years before Protagoras arrived in Athens. Buxton (1982) summarized the evidence as a set of manipulable polarities (62):

For example, he argues that a key theme of Aeschylus’ Suppliants (c. 460 BC) is that peitho is preferable to bia in both private and public spheres (Buxton 1982: 90). Just as with her secular fate, Peitho gained religious attention after the arrival of Protagoras. Both Isocrates and Demosthenes mention sacrifices to Peitho that make it clear Peitho began to be worshiped independently of Aphrodite Pandemos (Parker 1996: 234; Shapiro 1993: 202).

1.3 The Charites

The Charites, better known as the Three Graces, probably originated as agricultural gods. Rose (1958/1972) speculates that they “were pretty certainly to begin with agricultural deities whose function it was to make tilled ground look ‘winsome’ or ‘delightful’ because bearing a good crop” (16). Later they became deities who were also responsible for the things that bring people together, enhance life, “and induce men to accept gifts, especially a woman” (Tyrell and Brown 1991: 185). With regard to their worship, there was a shrine of the Charites associated with the archaic altar of Athena Nike near the Mycenaean entrance to the Acropolis

(Travlos 1971: 148).

Many groups of Charites were mentioned in poetry, “but no real myths about them and very little indication of any concrete function” (Gantz 1993: 54). All groups include a member who connotes brightness or light (Ann and Imel 1993: 145, 204, 206). Yet the “most widely accepted tradition” named the Charites as Aglaia, Euphrosyne and Thalia (Guirard 1963: 70). Like similar members in all other groups of Charites, Aglaia connoted brilliance, brightness, and splendor. She was said to preside at banquets, dances and social occasions (Ann and Imel 1993: 145). Euphrosyne, “she who rejoices the heart,” connoted mirth and hospitality (Guirard 1963: 70: Ann and Imel 1993: 174). Thalia, “she who brought flowers,” connoted gift giving and prosperity. She also later functioned as the Muse of comedy (Guirard 1963: 70; Ann and Imel 1993: 218). In sum, together the Charites connoted brilliance of style, symposia, and speeches of praise.

1.4 Hermes and Peitho

The meanings of both Hermes and Peitho become clearer when considering the contrast between peitho and dolos. Dolos can be translated as a “cunning trick” best exemplified by Hermes’ theft of Apollo’s cattle. Such cunning was a cardinal trait of Hermes. In most cases dolos is subversive, and is used to defeat a more powerful opponent (Buxton 1982: 64). In addition, when contrasted with dolos, peitho becomes frankness that is used to strengthen legitimate unions (65). Hence Peitho was usually portrayed speaking directly to an individual about to be married, while Hermes’ cunning, indirect designs could be promoted at a distance using mist, sleep, etc. Considering Hermes and Peitho together leads to consideration of two styles of speaking: direct and indirect. Also, Peitho’s connection to the interests of the state and Hermes’ connection to divination suggest what would later be called deliberation.

1.5 Hermes and the Charites

Hermes was “expressly assigned” to the Charites as their escort, and he was portrayed in that role in several places (Kerenyi 1944/1976: 110). For example, an archaic votive relief of Hermes and the Charites was displayed near Plato’s Academy (Travlos 1971: 51). Farnell (1909) believed these common representations showed Hermes leading the goddesses to the sacrifices being prepared for them, and perhaps connoted a role for Hermes as administering sacrifices for other gods (36). With regard to persuasion, the arrangement suggests that brilliance should follow invention, that brilliant words are direction less without clever ideas.

1.6 Peitho and the Charites

Peitho and the Charites were often depicted as attendants of Aphrodite (Rose 1958/1972: 55). In the Iliad, the Charites make a robe for Aphrodite; in the Odyssey, they bathe and dress her (Gantz 1993: 54). A surviving vase from the period of Protagoras’ stay in Athens explicitly links Peitho and the Charites at the birth of Aphrodite. Peitho pours a libation in her honor, while one of the Charites drapes a garment over her (Shapiro 1993: 200). In knowing Aphrodite’s secrets of adornment, they suggest that knowledge of what men desire is important to persuasion.

In Hesiod, the Charites help Peitho place the golden necklaces over Pandora’s head (68). Again the erotic and the publicly significant are conjoined. The conjunction might extend to the Charites also on those vases where Peitho is portrayed holding a flower in the midst of events linked to the Trojan War (Shapiro 1993: 190-92). Given their original nature as agricultural deities, they might well have been portrayed as blooming plants.

1.7 Hermes, Peitho, and the Charites

The five deities were grouped together in a few places during the archaic period. However, the total groups adds no extra meaning. With Hermes as a god of seduction, and with Peitho and the Charites knowing all Aphrodite’s secrets, this grouping might connote persuasion as sexual union. However, several facts make this interpretation unlikely. First, Hermes as a god of seduction and increase was grouped with the Nymphs, forest spirits without clear associations with the Charites or Peitho. Second, Hermes was never associated with plant fertility, as the Charites were (Farnell 1909: 11).

In addition, though Hermes and Aphrodite (so, through association, her attendants Peitho and the Charites) were linked in cults in several places, their connection stemmed from Aphrodite’s original nature as a Asian chthonic goddess (Farnell 1909: 653). Hermaphrodite was a child of Hermes and Aphrodite, but the Hermaphrodite myth occurs no earlier than Diodorus Siculus, who wrote during the late first century BC (Gantz 1993: 104). Finally, the Charites were not, during the archaic period, portrayed nude. Indeed, like Peitho, they were celibate. So, all five deities suggested the ideas of increase and prosperity, and the institution of marriage, but did not maintain these conditions through sexual union, but through clever words, frankness and brilliance.

In Hesiod, Hermes joins Peitho and the Charites in forming Pandora; he provides her with cunning and a knowledge of trickery (68). In the earliest surviving painted representation of Peitho, c. 510 BC, Hermes and the Charites join Peitho as she is about to crown Paris for making the right choice (Shapiro 1993: 189). In these two places, all five deities were implicated in events with simultaneous private and public significance.

A generation or two later, all five deities were represented on the Parthenon frieze and the throne of the Olympic Zeus, where the birth of Aphrodite was also portrayed (Farnell 1909: 705). So, just as with the individual deities, the whole group gained public significance after the arrival of Protagoras in Athens.

2. Reanalysis of the contributions of the sophists

Schiappa (1991) claims that Protagoras was “revolutionary” in his methods of teaching, and that with earlier philosophers he began a move toward prose and abstract expression from mythic-poetic expression. Based on the analysis of the five deities, Protagoras was not revolutionary, but was professionally successful because he fit well into Athenian mythic-poetic beliefs. In addition, Protagoras, later sophists, and Plato were not revolutionary because much that was associated with later dialogues about and manuals of rhetoric was already present in the mythic-poetic tradition. Finally, some of the elements of the mythic-poetic tradition were never translated into abstract, theoretical terms, so the tradition retained great power even as prose literacy grew.

Protagoras entered Athens using roads prominently marked with herms, and proclaimed himself a teacher of logos. As an itinerant teacher selling his services, he would seem to be claiming the protection and favor of Hermes whether he wanted to or not. As a traveler, a merchant, and a self-proclaimed inventor of useful instructional methods, he was triply associated with Hermes. As a proponent of debate, and a proclaimant of provocative, controversial aphorisms, he exhibited skills lent him by Hermes, and enjoyed a long, prosperous career as a result. A true historical reconstruction of Protagoras’ significance must take Greek social factors such as religion into account. These factors tend to temper claims about Protagoras’ and later sophists’ significance.

Protagoras did not write a practical manual of logos, and, if he did, it would have probably have been a collection of sample speeches (Schiappa 1991: 158). Such collections were new only in the sense that they were collections, for examples of speeches can be found throughout the Greek mythic-poetic tradition (Buxton 1982: 6-8). Yet the five deities associated with persuasion connoted much that would be treated in abstract, theoretical prose only much later than Protagoras. First, they suggested four of the later five “canons” of rhetoric: invention, style, arrangement, and memory. Specific techniques – three styles and a lost archaic art of memory – were also suggested. Since Peitho’s connection to good order was at one remove, it might be tempting to attribute the canon of arrangement to growing literacy. Yet it is important to keep in mind that while none of the five deities directly suggest arrangement, speeches presented as part of the mythic-poetic tradition did exhibit regular divisions.

Not only did the five deities suggest “canons,” they also suggested types or functions of persuasive speaking: forensic, eristic, deliberative, ambassadorial, and speeches of praise at symposia. Finally, the deities suggest several qualities of persuasion: it binds citizens together, despite economic tensions; it can be used to overcome a more powerful opponent; it requires knowledge of what men desire; it provides gifts, and can induce citizens to accept gifts; it can be used to mislead; and, it can be used to gain revenge. These “canons,” functions and qualities would not be systematically examined in abstract prose until Plato, Aristotle, and the author of the Rhetorica ad Alexandrum (c. 387-330 BC). Hence later theories of rhetoric can be seen in part as a working out and partial endorsement of the implications of the mythic-poetic tradition. Finally, Hermes unequivocally suggests ambassadorial speaking, a type of speaking that was never treated in an abstract, theoretical manner (Wooten 1973: 109). This is true even though Wooten argues that this type of speaking became increasingly important during the Hellenistic age (212). Hence some aspects of persuasion remained too sacred to be treated impersonally. Additionally, the five deities were worshiped more fervently at the same time as the mythic-poetic tradition was translated into prose. Representations of Hermes grew more youthful and widespread, Peitho began to be worshiped independently, and the Charites began to be represented on great state monuments at the same time that the sophists gained prominence.

Hence Protagoras deserves credit as one of the first prose writers, and as the inventor of new verb forms amenable to abstract expression. However, his personal circumstances and the content of his aphorisms fit perfectly well within the Greek mythic-poetic tradition, and the success of his and later sophists’ students might even have stimulated increased devotion to Hermes, Peitho, and the Charites.

Since the mythic conceptions of persuasion express much that would appear later in abstract prose, the contributions of later sophists must be differently assessed against the backdrop of the mythic-poetic tradition. Here, following Schiappa, I have focused especially on Protagoras. However, later sophist also deserve attention to determine their theories’ relationships to the views of persuasion implied by the mythic-poetic tradition.

REFERENCES

Ann, M., & D. M. Imel. (1993). Goddesses in World Mythology. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO.

Barthell, E. E., Jr. (1971). Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Greece. Coral Gables: Miami University Press.

Brown, N. O. (1917/1990). Hermes the Thief: The Evolution of a Myth. Great Barrington, Massachusetts: Lindisfarne Press.

Burkert, W. (1985). Greek Religion. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Buxton, R. G. A. (1982). Persuasion in Greek Tragedy: A Study of Peitho. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Farnell, L. R. (1896). The Cults of the Greek States. Vol. II. New York: Clarendon Press.

Farnell, L. R. (1909). The Cults of the Greek States. Vol. V. New York: Clarendon Press.

Gantz, T. (1993). Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Guirard, F. (1963). Greek Mythology. London: Paul Hamlyn.

Guthrie, W. K. C. (1950). The Greeks and Their Gods. Boston: Beacon Press.

Harrison, J. E. (1966). Epilogomena to the Study of Greek Religion and Themis: A Study of the Social Origins of Religion, New York: University Books.

Hesiod. (1983) Theogyny, Works and Days, Shield. Tr. Apostolos N. Athanassakis. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Kerenyi, K. (1944/1976). Hermes, Guide of Souls. Tr. Murray Stein. Woodstock, Connecticut: Spring Publications.

Kournouniotes, K., & H. A. Thompson. (1932). The Pnyx at Athens. Reprinted from Hesperia, I.

Parker, R. (1996). Athenian Religion: A History. New York: Clarendon Press.

Rose, H. J. (1958/1972). Gods and Heroes of the Greeks: An Introduction to Mythology. New York: World Publishing.

Sappho. (1958). Sappho: A New Translation. Tr. Mary Barnard. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Schiappa, E. (1991). Protagoras and Logos: A Study in Greek Philosophyand Rhetoric. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press.

Shapiro, H. A. (1993). Personification in Greek Art: The Representation of Abstract Concepts, 600 – 400 B. C., Zurich: Akanthus.

Simon, E. (1983). Festivals of Attica: An Archaeological Commentary. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Thompson, H. A. (1936). “Pnyx and Thesmophoria.” Hesperia 5, 151-200.

Travlos, J. (1971). Pictorial Dictionary of Ancient Athens. New York: Praeger Publishers.

Tyrell, W. B., & F. S. Brown. (1991). Athenian Myths and Institutions: Words in Action. New York: Oxford University Press.

Wooten, C. (1973). “The Ambassador’s Speech: A Particularly Hellenistic Genre of Oratory.” The Quarterly Journal of Speech 59, 209-12.

Yates, F. (1966). The Art of Memory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.