ISSA Proceedings 1998 – The Diagnostic Power Of The Stages Of Critical Discussion In The Analysis And Evaluation Of Problem-Solving Discussions

1. Introduction

1. Introduction

Problem-solving discussions, conducted in all situations where people jointly have to solve problems and reach decisions, are an important part of public as well as private life. Since considerable interests are often at stake, it is important that these discussions be carried out in such a way as to ensure that the best possible decision is reached. In view of the importance of safeguarding the quality of problem-solving discussions, it is relevant to develop instruments for analyzing and evaluating such discussions. These instruments should make it possible to establish whether participants act in a fashion that is conducive to the goals of problemsolving discussions, and, if not, in what respects, at what points in the discussion, and in what ways. Such an analysis of the ways in which discussions can go wrong will yield a basis for teaching participants how to avoid these counterproductive practices in future.

In this paper, I will show that the ideal model of critical discussion, which is central to the pragma-dialectical approach to argumentative discourse developed by Van Eemeren and Grootendorst (1984, 1992), provides a diagnostic instrument which may be used in carrying out such an analysis. The model specifies the stages of critical discussion through which rational resolution of a difference of opinion is attained, and the speech acts which have to be performed in each of these stages. So far, the model has been applied mainly as an heuristic and analytical instrument for the dialectical reconstruction of discursive texts (Van Eemeren et al. 1993) and as a framework for systematizing the various fallacies which may hinder the rational resolution of differences of opinion (Van Eemeren and Grootendorst 1984, 1992). I will demonstrate that the model can be used also for determining the quality of problem-solving discussions qua discussion, that is, as the medium through which the resolution of differences of opinion is accomplished. In a pragma-dialectic perspective, a discussion qua discussion is good if it provides optimal opportunity for the systematic critical testing of ideas. What this comes down to is that a good discussion is one which optimally enables the execution of the stages of critical discussion. The quality of a discussion qua discussion, then, may be determined by examining how well it enables the execution of the stages of critical discussion. In this paper, I will examine a real-life problem-solving discussion in this fashion, showing that an analysis along these lines enables the analyst to gain a rather precise insight into what went wrong in the discussion, in what respects, and why.[i]

2. The context of the discussion

The discussion took place during the staff meeting of an organization which initiates and manages co-counseling groups. Three of the participants, A, B, and D, are paid staff members of the organization: A and B full-time administrators, D a part-time group coordinator. The fourth one, C, is a volunteer, a representative of the group leaders. C and D are members of the training program committee; A and B regularly meet with the board of directors of the organization. The topic of the discussion is the organization of additional training for group leaders, after the one year of basic training which they receive. A has opened the discussion with the question “where does it belong”.

That something did go wrong in this particular discussion is certainly the opinion of at least two of the participants. After more than one hour of discussion without a decision having been reached, A, in line 1659, queries:

(1)

A: that would have to be something for that kind of committee.

1655C: but they’d have to have something to start from

A: but they’d [have] to have something to start from

D: [yes: hm]

(2)

A: and do we have any ideas on that, then

1660

(2)

because that’s one thing I’m worried about

After a fifteen (!) seconds pause, C gives the following answer:[ii]

(2)

C: well, so what they’d have to start from is the inventarization we’re going around in circles

1665A: ye::s [no but that’s what the problem]

C: [and we’ve been doing that] for the past hour or so,

C and A obviously are of the opinion that the discussion has got stuck.

As a first step towards uncovering what occasioned A and C’s complaint, I will briefly relate what points of view are brought forward in the discussion and how the linear process of trying to resolve the differences of opinion evolves.

After A’s introduction of the question, B briefly sketches the past situation and then argues for the view that the organization of additional training belongs to the domain of the training program committee: a standpoint which A, later in the discussion, also will advance. B’s arguments elicit no reaction; instead, D argues for his own point of view: he questions the need for additional training. A and B attack one of the two arguments which D adduces, but the one which he himself declares most important – the group leaders have never asked for additional training – remains undiscussed. C then brings up another point: who is supposed to pay for the training. During the ensuing discussion of this point, D repeatedly questions the need for additional training, but his questions receive no answer. C replies with practical proposals for finding out what possible topics for training might be and for integrating additional and basic training. The discussion ends in general banter about the financial state of the organization.

After this intermezzo B once again brings up for discussion the standpoint that the program committee should organize the training. D objects by pointing out that nobody on the committee can take on additional work. When B rejects this line of argument as merely practical, D brings in another argument: others may do the job just as well; he then once again poses the question what need there really is for additional training. B says she would like to discuss this question at another occasion, but C `answers’ it by bringing forward a standpoint of her own: before anything else, an inventory of the topics on which training is required must be taken; that is the only sensible basis for any policy at all. A counters that a committee charged with organizing the training could do this; C maintains that it should be done before appointing a committee, repeating her policy argument. A then changes tack. He points out that an agreement has already been made to organize additional training and that it is high time something were done about it. D denies the binding force of this agreement and claims that it is not at all clear what urgency there is for such training. C brings forward doubts of her own against the status of the agreement. The discussion bogs down in an exchange of reproaches.

A manages to soothe the parties and re-initiates the discussion about the question where the organization of additional training belongs. C responds by naming the sources for the inventory which she once again proposes. A doesn’t react to this, but argues for his own proposal to charge the program committee with the organization. C asks for a response to her proposal. A then repeats his own proposal and says it amounts to the same thing. B supports A’s proposal. C once more repeats her proposal. Asked for his opinion, D says he agrees, but only because it will show there is no need for additional training. When B reacts to this with the statement that added training always is necessary, C reiterates that an inventory of the topics on which training is needed must be taken first, A repeats his proposal to charge a committee with this task, and C repeats that first there needs to be an inventory. The discussion closes with both C and A lamenting the fact that the discussion is moving in circles, after which C unilaterally puts an end to the impasse by implementing her own proposal through distributing the tasks for inventarization among those present.

C and A’s lament, we can see now, is justified: the discussion has got stuck in a repetition of standpoints without any progress being made. C forces a breakthrough, but none of the differences of opinion have been resolved. In fact, the various standpoints have hardly been discussed at all.

A and B’s standpoint, that the organization of additional training belongs to the domain of the training program committee, receives direct discussion at only one point, when D argues against it by saying that it is not feasible and that there are other people who can be charged with the task. The first of these counterarguments is rejected as merely practical, the second receives no response at all. For the rest, C and D’s reactions concern the standpoint only indirectly; they address presuppositions of the question to which it is presented as an answer.

D’s standpoint, that there is no need for additional training, is only responded to with regard to a subordinate issue; his main point remains undiscussed. D’s questions regarding this need are reacted to by C with practical proposals for conducting an inventory and for integrating initial and additional training. A and B, implicitly or explicitly, declare these questions out of order.

C’s standpoint, that an inventory of the topics on which additional training is required must be taken first, is not discussed at all; A, who is C’s main opponent, does not respond to her arguments, but invariably replaces her proposal with his own one.

By investigating how the successive stages of critical discussion have been executed in this particular discussion, I think we can reach a diagnosis of how this unfortunate course of events could develop. I will deal with the stages in their order.

3. The confrontation stage

In the confrontation stage of a critical discussion, the differences of opinion which the discussion addresses must be externalized. Our discussion pertains to a multiple mixed difference of opinion: involved are three main standpoints and three contra- standpoints against these, and all of these standpoints meet with doubt. The three main standpoints are: additional training belongs to the domain of the program committee (A and B); it is unclear what the need for additional training would be (D); before anything else, an inventory of the topics on which additional training is required must be taken (C).

The three main standpoints are expressed, but this is not the case for the doubt against them, the contra-standpoints, and the doubt against these. That this doubt exists and that these contra-standpoints are being maintained can only be inferred from the fact that the participants repeatedly respond to the expressed standpoints by bringing forward a different standpoint of their own.

In itself, the fact that doubt and contra-standpoints are not expressed explicitly is not unusual, nor does it necessarily form an impediment to a proper execution of the procedure for resolution of a difference of opinion. But the fact that the various positions which the participants take have not been clarified, almost undoubtedly is one of the causes for the defective execution of the subsequent stages which we shall encounter below.

At another level, a more serious defect can be observed. Behind the differences of opinion which get talked about in the discussion, the existence of another difference of opinion may be divined; this one, however, is not talked about.

As A makes clear when he refers to the earlier agreement (in lines 850-880), the issue of additional training has been around for quite some time, without anything being done about it. A mentions that he even had to account for this to the board of directors:

(3)

A: That’s sort of the way it is the expectations of uh

D: yes

A: the board

D: yes [but]

940 A: [and and that]’s e- because of because I‘ve, yes, because I’m involved because of course I’ve mentioned that the other time I said well hh uh (.), the additional training, that was on the staff agenda, that was last time then we didn’t get to it ((…)), well, then there was a big hullabaloo right away, gee what a shame ((…))

955 you see, so that’s the expectation there

Later, A attributes this failure to execute the agreement to the training program committee (of which C and D are members):

(4)

A: I’m also to blame for this myself I think, but I think, like, the program committee

1065 as well as far as that is con- if there would have been time for that so to speak, huh, or space at least that is my estimation, I don’t know whether that is the case, then that could’ve been worked out (.) or faster. right? but now

This opinion doesn’t surface until almost three-quarters of the discussion has gone by and it is at no point explicitly made into an issue for discussion. Earlier in the discussion, it is mirrored only indirectly in the content of A and B’s standpoints: the organization of additional training is the province of the program committee.

D, in turn, feels that he cannot be expected to take this task on in the context of the part-time job which he holds. That comes out most clearly in the part of the discussion in which the participants engage in reciprocal reproaches:

(5)

B: yes well I think you as a member of the program committee, that it’s up to you

1130 to fill in the details on that. how is a board supposed to know, hh

D: make it into a full-time job then, then I’ll do it

D, too, fails to make this opinion of his into an explicit issue for discussion. It only indirectly surfaces in the fact that, whenever A and B try to assign the committee of which he is a member the task of organizing added training, D puts the need for this training into question.

4. The opening stage

In the opening stage the roles of protagonist and antagonist must be distributed and the shared starting points for the discussion must be established. In our discussion, neither of these tasks gets performed properly.

All participants have the role of protagonist for their own standpoints. In addition, they all have the role of antagonist against the other two standpoints and that of protagonist for the contra-standpoints against the same. In our discussion, however, the latter two roles do not get performed adequately. The participants hardly address each other’s arguments and points of view. They argue almost exclusively in favor of their own standpoints. They thus simply replace one standpoint by another, without subjecting the replaced standpoints to any criticism. They don’t seem to realize that taking a different point of view implies doubt and a contra-position, which carries a burden of proof, against the original one. This may very well be a consequence of the fact that in the confrontation stage the various positions of the participants were not clarified.

As to the shared starting points: one of these is certainly that at some point and by someone an inventory must be made of the topics on which additional training is required. This idea is a presupposition of a number of contributions of various participants, and it is challenged by no one. But the fact that it is a common starting point is not established by any one. In itself, that is not strange – common starting points typically remain implicit -, nor is it particularly wrong, but the discussion could have been simplified considerably if it had been. The discussion could then have been reduced to the questions of when and by whom the inventory should be taken.

More serious is the fact that on other issues there exists a profound but unacknowledged difference of opinion as to what belongs to the common ground. On the one hand, according to D, before the question of where additional training belongs can be discussed, there must be agreement about the need for such training, and according to C, data must be available about the topics for which this training is required. Neither agreement nor data exist. So, with neither whether nor what established, A and B demand an answer to where. A and B, on the other hand, take it for granted that there exists a long-standing agreement to organize additional training, and that it is merely a question of who is going to do it. Whether and what are no longer relevant issues, according to them.

The result of this implicit difference of opinion as to what does and does not belong to the common ground, is that the discussion cannot progress. Every time A and B pose the question where, D and C return to the questions whether and what. And those questions cannot be answered in the discussion because A and B consider them no longer relevant.

5. The argumentation stage

In the argumentation stage, the protagonist brings forward argumentation for his standpoint, to which the antagonist critically responds. In our discussion, the execution of this stage is flawed in several respects. Partly, this is the direct result of the inadequate division of dialectical roles mentioned above: the participants hardly react to the standpoints and arguments of the other party. A crass example of this is A, who does not at all respond to C’s proposal, but instead presents one of his own, and when B and C protest and demand a reaction, repeats his own proposal and claims it boils down to the same thing.

But in other respects as well, the connection between the various contributions is rather loose. This applies, for one thing, to the local relevance of these contributions. Many of them relate only superficially to the preceding utterances of the co-participants. Examples are the passages where D asks whether there is any need for additional training, and C replies with practical proposals for finding out what possible topics for training might be and for integrating additional and basic training. The recurrent absence of local relevance results in conceptual confusion, talking at cross purposes, false agreement and, in the end, a fragmentary discussion of the standpoints.

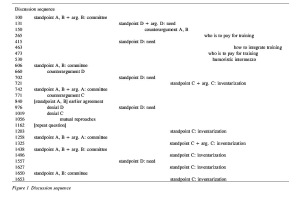

Overall relevance, as well, is less than ideal. The participants hardly seem aware of the main thread of the dispute. Digressions abound. As a result, the discussion takes a meandering course (see Figure 1: discussion sequence). A topic or proposal will get discussed for a shorter or longer while, but every time, before the discussion is brought to a close, another topic emerges, which in turn is not dealt with decisively, after which earlier topics once again come into focus, are again not dealt with decisively, etcetera, without, and that is the point, any progress being made.[iii]

6. The closing stage

In the closing stage, the results of the defence of the standpoints, which has been undertaken in the argumentation stage, are determined. If a standpoint has been defended successfully, the antagonist must withdraw his doubt; if the standpoint has not been defended successfully, the protagonist must withdraw it. In our discussion, this stage, too, is only partially performed.

Apparently, since every one in the end cooperates in implementing C’s proposal, that is the proposal which all participants accept. In itself, that is not surprising, since no one has objected to the idea of inventarization. But the other proposals have not been refuted, nor have they been retracted. A keeps on defending his proposal to the very last, even when B voices agreement with C’s. D, too, maintains his own standpoint; he combines it with C’s. In addition, the `acceptance’ of C’s standpoint is not the result of a weighing of the different standpoints. Such an assessment simply has not taken place. In pragma-dialectical terms, then, the difference of opinion has been settled, not resolved.

In large part, the inadequate execution of the closing stage can be traced back to the deficiencies in the preceding stages which I have pointed out. Because the different positions of the participants with regard to each other’s standpoints have not been clearly explicated, making up the balance becomes more difficult. Because the participants mainly take on the role of protagonist for their own standpoints, other standpoints and arguments have not been scrutinized critically and therefore cannot be rejected or accepted on the basis of a critical assessment. And, finally, such assessment is hindered by the fact that the participants hardly have any awareness of the main thread of the dispute: they lack an overview of what has been adduced pro and contra the different standpoints.

7. Conclusions

In this paper, I have examined a problem-solving discussion which the participants themselves declared unsatisfactory. I outlined the development of the discussion and pointed out what went wrong. The participants turned out hardly to have responded to one another’s standpoints and arguments. As a result, with regard to none of the three main standpoints could the differences of opinion be resolved. By looking at the way the stages of critical discussion were executed in this discussion, I then was able to establish how exactly this had come about. None of these stages turned out to have been performed fully. In the confrontation stage, the various positions of the participants were not clearly explicated, nor was the underlying difference of opinion brought out and put up for discussion. In the opening stage, the positions of antagonist and of protagonist of the contra-standpoint were not taken on, nor was there full agreement about the starting points for the discussion. In the argumentation stage, contributions often were only loosely connected, and in the closing stage no assessment was made of the various positions. Through this analysis, then, the sources of the unfortunate development of the discussion could be established.

To be sure, the analysis carried out in this paper only revealed whether the discussion process did enable the procedure for resolution of a difference of opinion. I did not establish how well this procedure itself was carried out. That would imply evaluating the substance of the moves which were made: whether contradictions and inconsistencies were present, whether any fallacies were committed, what the quality of the arguments was, and whether the assessment of these arguments was appropriate. My purpose in this paper has been solely to demonstrate that the model of critical discussion can be used fruitfully as a diagnostic instrument in the evaluation of problem-solving discussions qua discussion, that is as a process creating the conditions for rational resolution of a difference of opinion. I might as well mention here that in view of this purpose something else was not done, either: I did not present a detailed account of my reconstruction of the positions of the participants and of the moves they made in the discussion.[iv] Obviously, in a full analysis and evaluation all of these tasks must be performed.

The process-oriented diagnostic use of the model of a critical discussion which I have demonstrated in this paper has several advantages. In the first place, because it focusses on the interactional processes between participants, it gives perspective on some of the deeper, social causes of the derailment of discussions. In this discussion, for instance, it turns out that there is a conflict of interests, connected with the different institutional positions of the participants, which hinders the progression of the discussion. A and B, who try to obtain a decision as to where the organization of additional training should be placed, are policy-making staff members who regularly meet with the board of directors of the organization and who have to set things in motion. C and D, who launch concrete questions and objections regarding the need for and the content of additional training, stand, as volunteer group leader and group coordinator, respectively, and as members of the training program committee, with both feet in the arena of practical action. They are the ones who have to put the proposals of the policy-makers into effect. Obviously, the interests and responsibilities of these two parties differ. This difference is at the root of the different positions which they take in the discussion and of their persistence in maintaining these positions.

In the second place, applying the model of critical discussion makes it possible to enumerate the tasks which, if performed, create the conditions for a discussion to issue in as good a decision as possible. These tasks would include: making sure that the different standpoints which are at stake are explicitized, encouraging participants to react critically to standpoints and arguments, stimulating participants to take stock of their common ground, keeping an eye on the main thread of the discussion, providing summaries of arguments pro and con, guarding against digressions, making relevant distinctions, ensuring critical final assessment of all positions, etcetera. A list like this, derived from the steps which should be taken in the different stages of critical discussion, may help participants in problem-solving discussions to improve the quality of their participation: it may thus provide an instrument for safeguarding the quality of problem-solving discussions.[v]

NOTES

[i] That it is justified to analyze problem-solving discussions as critical discussions, is argued in Van Rees (1991).

[ii] Most pauses last no longer than one second (Jefferson 1989).

[iii] In itself, such a meandering course is not unusual, but ordinarily, contrary to what happens here, it produces progress towards consensus (see Fisher 1980).

[iv] How such an account can be given, is demonstrated in Van Rees (1995, 1996).

[v] There is a point here which may be so self-evident as to escape notice. The concept of critical discussion makes it possible to develop a workable conception of quality. So far, quality of problem-solving discussions has been an extremely unmanageable notion (Hirokawa et al. 1996). In a pragma-dialectical framework, a precise elaboration of this concept becomes possible: the quality of a discussion is directly linked to the degree to which it enables the rational solution of a conflict of opinion.

REFERENCES

Eemeren, F.H. van & Grootendorst, R. (1984). Speech Acts in Argumentative Discussions. A Theoretical Model for the Analysis of Discussions Directed towards Solving Conflicts of Opinion. Dordrecht: Foris/Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Eemeren, F.H. van & Grootendorst, R. (1992). Argumentation, Communication, and Fallacies. A Pragma-dialectical Perspective. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Ass.

Eemeren, F.H. van, R. Grootendorst, S. Jackson & S. Jacobs (1993). Reconstructing Argumentative Discourse. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press.

Fisher, B. A.: 1980. Small Group Decision Making: Communication and the Group Process. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Hirokawa, R.Y., L. Erbert & A. Hurst (1996). Communication and group decision-making effectiveness. In: R.Y. Hirokawa & M.S. Poole (Eds.), Communication and Group Decision Making (pp. 269-301), Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Jefferson, G. (1989). Notes on a possible metric which provides for a “standard maximum silence” of approximately one second in conversation. In: D. Roger & P. Bull (Eds.), Conversation: an Interdisciplinary Perspective (pp. 166-196), Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Rees, M.A. van (1991). Problem solving and critical discussion. In: F.H.van Eemeren e.a. (Eds.), Argumentation Illuminated (pp. 281-292), Amsterdam: Sicsat.

Rees, M.A. van (1995). Analyzing and Evaluating Problem-Solving Discussions. Argumentation, 9, 343-362.

Rees, M.A. van (1996). Accounting for transformations in the dialectical reconstruction of argumentative discourse. In: J. van Benthem, F.H. van Eemeren, R. Grootendorst & F. Veltman (eds.), Logic and argumentation. KNAW Verhandelingen, Nieuwe Reeks, 170 (pp. 89-100), Amsterdam: North-Holland.