ISSA Proceedings 1998 – What Went Wrong In The Ball-Point Case? An Analysis And Evaluation Of The Discussion In The Ball-Point Case From The Perspective Of A Rational Discussion

1. Introduction

1. Introduction

In May 1991 a 53-year old woman is found dead in her house. Pathological investigation shows that she has a BIC ball-point inside her head, behind her eye. An accident? A murder-case? The finding is the introduction to one of the most interesting and complex criminal cases of the last years in the Netherlands. The former husband and the son are under suspicion. Rumour has it that the son, during his school years, has referred to the perfect murder more than once. Finally, in 1994, J.T., the son, is arrested. This is done after the police were given a statement by a psycho-therapist in which this therapist contended that the son confessed to her that he killed his mother. He would have shot a BIC ball-point with a small crossbow. On the basis of this statement of the therapist, who wanted to remain an anonymous witness, in combination with the statement of the forensic pathologist and the statement of the police, the prosecutor starts a criminal procedure.

The District Court sentences J.T. on September 29, 1995 for murder to twelve years imprisonment. J.T. appeals and after many procedural complications he is finally acquitted by the Court of Appeals in 1996. The Court of Appeals is of the opinion that, on the basis of what is said by the expert witnesses, it is not possible to formulate a hypothesis of what has actually happened. The expert witnesses, the witness on behalf of defense and the witness on behalf of the prosecution, all testify that when a ball-point is shot at a human head with a crossbow, this always results in a damage to the pen when it penetrates into the head. Therefore, it is impossible to shoot a ball-point at a human head with a crossbow without damaging the pen, as would have happened in this case. The Court also says that, because it could not find a convincing support for the statements of the therapist on the basis of other information, it could not decide that the statements of the therapist are in accordance with what has actually happened. Therefore the indicted fact could not be proven beyond reasonable doubt.

Not only in the media, but also among lawyers, this so-called ‘ball-point’ case raised many questions with respect to the quality of the Dutch criminal system. A lot of mistakes would have been made by the police and by the courts during the trial with respect to the way in which the evidence was handled. Because of my own background as an argumentation theorist, I would like to concentrate on the question what could be said about this case from an argumentative point of view: what went wrong in the discussion about the evidence from the perspective of a rational argumentative discussion? In the reviews of this case, generally speaking, two important points of critique can be distinguished.[i]

The first point is that the decision of the district court was mainly based on the statement of the therapist, which turned out to be a very weak element. The second point of criticism is that the court did not engage in an explicit discussion of the accident theory, that the woman had fallen in the ball-point by accident.

These two points amount to the critique that the argumentation in the justification of the District court was unsatisfactory with respect to the central question whether J.T. had indeed killed his mother. According to the official rules and the official practice of district courts in criminal cases, the court has done nothing wrong. But considered from the perpective of a fair trial ànd considered from the perspective of a rational argumentative discussion, the argumentation of the District Court can be criticized in several respects.

What I would like to do is to go into these points of critique from the perspective of argumentation theory. I will use the pragma-dialectical theory of Van Eemeren and Grootendorst developed in Argumentation, communication, and fallacies (1992) (also known as the theory of the Amsterdam School) as a magnifying glass for highlighting those aspects of the ball-point case which can be criticized from the idealized perspective of a rational discussion. I will use this theory for analyzing and evaluating the ball-point case from the perspective of a rational argumentative discussion. I will connect my analysis and evaluation wit ideas developed by Anderson and Twining (1991 and 1994) and by Wagenaar, van Koppen and Crombag (1993) about ideal norms for the assessment of evidence in criminal cases.

2. The analysis of the argumentation in the ball-point case

To establish whether the argumentation put forward in defence of a legal position is sound, first an analysis must be made of the elements which are important to the evaluation of the argumentation. In the evaluation based on this analysis the question must be answered whether the arguments can withstand rational critique. In a so-called rational reconstruction an analysis of the argumentation is made in which the elements which are relevant for a rational evaluation are represented.[ii]

The aim of the analysis is to reconstruct the argumentation put forward by the various participants to the discussion and to reconstruct the structure of the discussion with respect to the question which parts of the argumentation have been attacked. The aim of the evaluation is to determine whether a standpoint has been defended successfully against the critical reactions put forward by the various antagonists during the discussion in accordance with the rules for a rational legal discussion.[iii]

2.1 The reconstruction of the argumentation structure

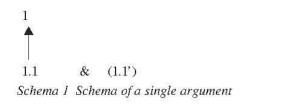

In the reconstruction of the argumentation in the ball-point case I will use various analytical concepts developed in pragmadialectical theory. In the reconstruction, a pragma-dialectical approach distinguishes between various forms of argumentation.[iv] In the most simple case, called a single argument, the argumentation consists of just one argument with, usually, one explicit (1.1) and one unexpressed premise (1.1’). Represented schematically (I):

Often the argumentation is more complex, which means that there are more arguments put forward in defence of the standpoint. When a legal standpoint is supported by more than one argument, the connections between these arguments may differ in nature. Van Eemeren et al. (1996) distinguish various forms of complex argumentation, depending on the types of connection between the single arguments. They distinguish between multiple (alternative) argumentation in which each argument constitutes in itself sufficient support for the standpoint; coordinatively compound (cumulative) argumentation in which a number of arguments are linked horizontally and which provide in conjunction a sufficient support for the standpoint; and subordinate argumentation in which a number of arguments are linked vertically and which provide in conjunction a sufficient support for the standpoint.[v]

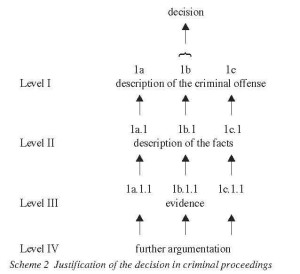

The justification of the decision of the judge in a criminal process in general consists of a complex argumentation, consisting of various ‘levels’ of subordinate argumentation. On the first level (I), the argumentation consists of compound argumentation consisting of a description of the criminal offense. On the second level (II), the argumentation consists of several single arguments, describing the facts which form instances of the components of the criminal offence. On the third level (III), the argumentation consists of a number of single arguments, the evidence for these facts. The argumentation on level III is sometimes defended by further argumentation of the fourth level (IV). In scheme (II):

The decision of the District Court in the ball-point case is that the accused must be sentenced with an imprisonment of twelve years. This standpoint is based on the coordinative compound argumentation (argumentation on level I) that, because certain facts can be considered as proven, ànd that these facts constitute an instance of the criminal offense of clause 289 of the Dutch Criminal Code, and that the accused is guilty, the punishment which is connected to this criminal offense must be applied[vi]:

The argumentation on level II in defence of the components of 1a, 1b and 1c consists of a description of the concrete facts. The concrete facts, in turn, are each defended by single arguments which imply that the court ‘believes’ the evidence as presented (argumentation level III). As a defence of the supportive force of the statements of the therapist (9) the court puts forward the argumentation on level IV).

In the reconstruction this argument (13) is represented in the form of the two separate supporting arguments 1a.1a.1 and 1a.1b.1, which have an identical content. Schema (3) describes the arguments on the various levels and (4) gives a schematic representation. The decimal numbers reflect the pragma-dialectical hierarchy. I have used the numbers 1-13 for reasons of efficiency: it is easier to refer to these numbers.

Scheme 3: Argumentation of the district court

Decision: The accused must be punished with an imprisonment of twelve years.

1a intentionally and with forethought killed (1)

1a.1a We are justified in believing that it is proven beyond reasonable doubt that J.T. acted intentionally and after clear thought and pre-meditated (4)

1a.1a.1 We are justified in believing in the trustworthiness of the statements of the therapist that J.T. confessed to her that he, intentionally and after clear thought and premeditated, shot a ball-point through one of her eyes into the head with a small crossbow (9)

1a.1a.1.1 The District Court found her statement consistent and convincing (13)

1a.1b We are justified in believing that it is proven beyond reasonable doubt that he shot a ball-point through one of her eyes into the head with a small crossbow (5)

1a.1b.1 We are justified in believing in the trustworthiness of the statements of the therapist that J.T. confessed to her that he, intentionally and after clear thought and premeditated, shot a ball-point through one of her eyes into the head with a small crossbow (9)

1a.1b.1.1 The District Court found her statement consistent and convincing (13)

1a.1c We are justified in believing that it is proven beyond reasonable doubt that Mrs. de M. died as a result of the fact that J.T. shot a ball-point through one of her eyes with a small crossbow (6)

1a.1c.1 We are justified in believing in the trustworthiness of the statements of the coroner’s report (10)

1b On or about May 25, 1991 in Leiden (2)

1b.1 then and there (7)

1b.1.1 We are justified in believing in the trustworthiness of the statements in the police report on the finding of the body (11)

1c a woman named Mrs. de M. (3)

1c.1 a woman named Mrs. de M. (8)

1c.1.1 We are justified in believing in the trustworthiness of the statements in the police report on the investigation by the coroner (12)

2.2 The reconstruction of missing premises

In the reconstruction of the argumentation, all the argumentative steps must be made explicit. As we have seen, by reconstructing the argumentation structure, we get a clear picture of the various arguments put forward in defence of a standpoint and of the relations between these arguments. In such a reconstruction it becomes clear that many argumentative steps remain implicit, and it is the task of the analyst to give a rational reconstruction of these implicit arguments.

When reconstructing implicit arguments an analyst can use logical as well as pragmatic insights.[vii] To establish what has been left unexpressed from a logical perspective, the analyst must try to find out which statement is necessary to make the argument logically valid. If an arguer is sincere and does not believe that his argumentation is futile, this means that he assumes that others will be inclined to apply the same criteria of acceptability as himself.

These criteria will include the criterion of logical validity. Therefore, the analyst must examine whether it is possible to complement the invalid argument in such a way that it becomes valid. From a pragmatic perspective, however, the premis which makes the argument logically valid, the so-called logical minimum, sometimes contributes nothing new and is, therefore, superfluous. To try to make the missing premiss more informative, the analyst can try to formulate the so-called pragmatic optimum which complies with all the rules of communication. Often, this is a matter of generalizing the logical minimum, making it as informative as possible without ascribing unwarranted commitments to the arguer and formulating it in a colloquial way that fits in with the rest of the argumentative discourse.

In the analytical overview of the District Court, on various levels bridging arguments must be made explicit. Because our main concern is the argumentation with respect to the evidence, I concentrate on the argumentation on level III and IV of the argumentation where the various elements of the evidence are located and where the force of the evidence is justified. On these levels, various arguments must be made explicit.

A reconstruction of the arguments and missing premises on which the discussion in the procedure before the District Court centres is given in schema (5). The arguments 9’ and 13’ are the bridging arguments for the argumentation consisting of 9 and 13.

Scheme 5 : Reconstruction of missing premises

A

5 We are justified in believing that it is proven beyond reasonable doubt that he shot a ball-point through one of her eyes into the head with a small crossbow

because

9 We are justified in believing in the trustworthiness of the statements of the therapist that J.T. confessed to her that he, intentionally and after clear thought and premeditated, shot a ball-point through one of her eyes into the head with a small crossbow

and

(9’) If we are justified in believing in the trustworthiness of the statements of the therapist that J.T. confessed to her that he, intentionally and after clear thought and premeditated, shot a ball-point through one of her eyes into the head with a small crossbow, then we are justified in believing that it is proven beyond reasonable doubt that he shot a ball-point through one of her eyes into the head with a small crossbow

B

9 We are justified in believing in the trustworthiness of the statements of the therapist that J.T. confessed to her that he, intentionally and after clear thought and premeditated, shot a ball-point through one of her eyes into the head with a small crossbow

because

13 We find the statement of the therapist consistent and convincing

(13’) If we find the statement of the therapist consistent and convincing, then we are justified in believing the trustworthiness of the statements of the therapist that J.T. confessed to her that he, intentionally and after clear thought and premeditated, shot a ball-point through one of her eyes into the head with a small crossbow

These arguments 9’ and 13’ form essential steps in the argumentation of the District Court. In the evaluation it must be checked whether the explicit and implicit arguments can withstand rational critique.[viii]

3. The evaluation of the argumentation in the ball-point case

In a pragma-dialectical approach, the aim of the evaluation is to establish whether the protagonist has succeeded in defending his standpoint sufficiently. For the evaluation of the argumentation of the ball-point case, this implies that we must establish whether the argumentation of the District Court is acceptable if we submit it to the various critical tests of a pragma-dialectical evaluation.

In a pragma-dialectical evaluation the rules for a successful defence concern the question of whether the protagonist has successfully defended the initial point of view and subordinate points of view (arguments) called into question by the antagonist.[ix] The protagonist has successfully defended an argument against an attack by the antagonist if the propositional content of the argumentation is identical to a common starting point and if the argumentation scheme underlying the argumentation is appropriate and applied correctly.[x]

So, in our evaluation we must check whether the arguments of the District Court which have been called into question are acceptable and whether the argumentation scheme underlying the argumentation is applied correctly. First I will focus on the acceptability of the line of argumentation defending (1) which forms the central point of discussion. Then I will go into the question whether the District Court has responded adequately to other attacks by the defense.

In the evaluation of the acceptability of the line of argumentation supporting 1, the relevant question to be answered is whether the argumentation schemes underlying the argumentation in defence of (1) are applied correctly. This implies that it must be checked whether all relevant critical questions belonging to the argumentation scheme can be answered satisfactorily. Which argumentation schemes underlie the argumentation for the evidence in the decision of the District Court?[xi]

As we have seen, the support for 1a (1) consists of the arguments reconstructed as the arguments 4,5,6 (see schema 3 and 4). The support for these arguments consists of 9, 10 and 13 (and 13’). Because the acceptability of the argumentation consisting of 9 is dependent on the argumentation consisting of 13 and 13’, we must submit the latter to a critical test.[xii] The argumentation consisting of 13 and 13’ is based on an argumentation scheme which, in pragma-dialectical terms, expresses a symptomatic relation.[xiii] The court tries to defend its decision that X has property Z by pointing out that something, Y, is characteristic for Z:

Scheme 6 : Argumentation scheme of symptomatic argumentation

X has property Z because

X has (the characteristic) property Y and

Y is characteristic for Z

The critical reactions that are relevant to this type of argumentation scheme are the following evaluative questions:

1. Is Y valid for X?

2. Is Y really characteristic for Z?

3. Are there any other characteristics (Y’) which X must have in order to attach characteristic Z to X?

Question (1) is a general question which asks for a justification for the acceptability of the argument. Question (2) and (3) are questions which are specific for the argumentation scheme of a symptomatic relation. Question (2) implies that we ask whether property Y is indeed an intrinsic property. To answer this question in a satisfactory way, the protagonist will have to present subordinate argumentation to show that it is indeed an intrinsic property. Question (3) implies that the antagonist is of the opinion that Y is indeed a characteristic property, but thinks that it is necessary to mention more properties in order to call something Z. To answer this question in a satisfactory way, the protagonist must put forward compound argumentation in which he mentions other characteristics of Z and shows that these characteristics are present in the case at hand. So if the antagonist raises his doubts by posing question (2) and/or (3), he thinks that the argumentation is not sufficient and he forces the protagonist to supplement his argumentation with additional arguments. The relevant evaluative questions for the argumentation of the District Court are:

1. Is it really justified to believe that the statement of the therapist was consistent and convincing (Y)?

2. Is being justified in believing that the statement of the therapist was consistent and convincing (Y) really a good reason for being justified in believing in the trustworthiness of the statements of the therapist that J.T. confessed to her that he shot a ball-point through one of her eyes into the head with a small crossbow (Z)?

3. Is it not possible to think of other relevant and necessary considerations (Y’) for being justified in believing in the trustworthiness of the statements of the therapist that J.T. confessed to her that he shot a ball-point through one of her eyes into the head with a small crossbow (Z)?

The acceptability of the argument depends on the question whether these questions can be answered satisfactorily.

With respect to the answer to question 1 we could raise our doubts with respect to the fact that her statement was really consistent and convincing. The court does not explain in which respects the statement is consistent and why it is convinced by the statement of the therapist. What we miss here is an explanation of the considerations which made that the court felt convinced. So, from the perspective of a rational discussion we could say that the answer to the first question is ‘no’, and the court would have to put forward supporting subordinate argumentation. (Apart from this, the argumentation seems circular: in order to be convinced of the truth of the statement the Court puts forward the argument that the statement is convincing.)[xiv]

With respect to the answer to question 2 we could raise our doubts with respect to the fact that consistency is a sufficient reason for being justified in believing what the therapist has stated. In other words, are there any other considerations which are also relevant for the trustworthiness of her statement and can the earlier mentioned considerations form a sufficient ground in the absence of the later mentioned considerations? In this context, we could say that from empirical research we know that consistency of the statements of a witness is not always a guarantee for the truth of these statements.[xv] So, to be able to show that the second question can be answered satisfactorily, the court would have to put forward supporting arguments.

With respect to the answer to question 3 we could refer to the considerations given in the answer to the second question. Are there any other relevant considerations for believing in the statement, and if these considerations are present, why are they not applied?

Furthermore, we could say that such a ‘double de auditu’ statement must be submitted to more rigorous tests than the relatively weak criterion of consistency alone. So, to be able to show that the third question can be answered satisfactorily, the court would have to put forward compound argumentation. So, what we miss in the argumentation of the court from the perspective or a rational discussion is a further elaboration on the grounds on which the court has decided that the statement of the therapist is convincing, and whether it meets other requirements of a trustworthy account of the behaviour of J.T and of his explanations for his behaviour. Further arguments supporting 13 and 13’ are required.

These further arguments which are needed as a support of 13 and 13’ could be characterized as what Anderson calls the background generalizations upon which the relevance of the evidence rests. Wagenaar et al. (1993) call these considerations the commonsense presumptions which underlie the probative value of the evidence. These presumptions serve as the ‘anchors’ which constitute on various levels the ‘sub-stories’ on which the evidence is based. Twining calls them the commonsense generalizations or background generalizations, the generalizations that are left implicit in ordinary discourse. According to these authors, these commonsense background generalizations must be made explicit in order to assess their acceptability. In pragma-dialectical terms, the acceptability depends on the question whether they correspond with certain starting points which are acceptable to the participants.[xvi]

According to Anderson and Twining (1991), in most cases these generalisations are indeterminate and vague and subject to exceptions. According to Twining, the problem with these generalizations is that they are at the same time necessary and dangerous. They are necessary as the glue in inferential reasoning, and, as a last resort as anchors for parts of a story for which no particular evidence is available. They are necessary as providing the only available basis for constructing rational arguments. They are at the same time dangerous because, especially when unexpressed, they are often indeterminate in respect of frequency, level of abstraction, empirical reliability, defeasibility, identity (which generalization?).

The danger is that these implicit value judgements are presented as if they were empirical facts or empirical rules of experience. In my analysis of the argumentation of the District Court I have shown how the hierarchical relations between the various arguments can be reconstructed and which implicit arguments must be made explicit. On the basis of this analysis, in combination with the critical evaluation it becomes clear what the weak points of the argumentation of the District Court are. In my opinion, such a rational reconstruction gives a clear answer to the question which ‘anchors’ or ‘common-sense presumptions’ or ‘background generalisations’ exactly underlie the decision from an argumentative perspective and how these hidden assumptions can be criticized.

Because, in the present form, the argumentation consisting of 13 and 13’ is not acceptable, and these arguments form the final basis in a subordinate line of argumentation for argument (1) (1a), (1) is not acceptable from the perspective of a rational discussion. Because 13 and 13’ form subordinate argumentation for (9), (9) is not acceptable, and because (9) forms subordinate argumentation for (4) and (5), these are not acceptable. And because (4) and (5) form together with (6) compound argumentation for (1), (1) is not acceptable.

So, according to the pragma-dialectical rules, the argumentation is not acceptable. This result is in line with the rules for anchoring the narrative supporting the decision developed by Wagenaar et al. (1993). According to their rule (3), essential components of the narrative must be anchored, according to their rule (5) the court must give reasons for the decision by specifying the narrative and the accompanying anchoring, and according to rule (6) the court should explain the general beliefs used as anchors. As we have seen, this is not the case. Argument (13) needs support by anchors explaining why the court believes in the truth of the statement of the therapist.

Our final judgement about the argumentation line supporting argument (1) (1a) is therefore that it has not been justified beyond reasonable doubt that J.T. has killed his mother by shooting a ball-point through one of her eyes into the head with a small crossbow. Because this argument forms part of compound argumentation, this implies that the decision has not been defended successfully.

Considered from the perspective of the ideal norms formulated in the pragma-dialectical theory and Wagenaar et al. and from the perspective of the dangerous character of generalisations as described by Anderson and Twining, the cause of the weakness of the argumentation of the District Court lies in the fact that the basis for its argumentation is not acceptable because it does not specify the criteria for the use and the reasons for belief in the statements of the expert witness. The implicit argument (13’) underlying the argumentation can be criticized in many respects and therefore cannot function as a final basis for the argumentation.

Apart from this point of critique, there is a second reason why the argumentation of the District Court with respect to argument (1a) does not meet the requirements of a rational legal discussion. One of the contra-arguments of the defense was that there was another plausible explanation for the presence of the BIC ball-point in the head of Mrs. de M. The defence puts forward the testimony of three experts, Worst, Van Rij and Visser. Worst and van Rij are of the opinion that there is no other explanation for Mrs. de M’s death than that she accidentally fell on the ball-point, Visser thinks this explanation of the cause of death equally plausible as the murder theory.

On behalf of the defense, the ophthalmologists Worst and van Rij contend that the fall theory is the most likely explanation of the death of Mrs. de M. In his capacity as an expert witness, Worst contends that Mrs. de M. most likely died because of a complicated, purely accidental, fall into the BIC ball-point. The ophthalmologist van Rij confirms this opinion. He contends that the most probable cause of death of Mrs. de M. is that she fell into the BIC ball-point. According to him, murder by which the ball-point has been shot into the eye by means of a shooting weapon is most un-likely. The pathologist Visser (who has been present at the autopsy) contends in his capacity as expert witness that he does not agree with Worst’s opinion that a fall into the ball-point is the most probable cause of death, but he does not say that it is an unlikely cause, and thus does not exclude the accident theory. According to him there are three equally plausible causes of death: an accident, suicide, and murder.

However, the District Court does not reply to the contra-argument of the defense: it does not answer the question why the ‘story’ that the death of Mrs. de M. is caused by a shot of the ball-point with a small crossbow is more plausible than the ‘story’ that her death is caused by a fall into the ball-point. We could say that, because the District Court does not refute the accident theory put forward by the two experts Worst and Van Rij (which is not denied by the third expert, the pathologist Visser) it does adequately answer the counter-arguments put forward by the defense, and therefore according to the pragma-dialectical rules (10 and 11) has not defended successfully argument (1) against attacks of the antagonist.

With respect to this point, the evaluation is in tune with the rules developed by Wagenaar et al. (1993). According to their rule (7), there should be no competing story with equally good or better anchoring. Because the ‘story’ of Worst and van Rij has not been refuted by Visser, there is no reason to doubt the quality of its anchoring, and therefore the argumentation of the District Court does not meet the requirement of rule 7.

So, according to our ideal norms for a rational discussion in criminal proceedings the justification of the District Court is not acceptable on this second point.

4.Conclusion

I have shown what went wrong in the ball-point case from the perspective of an idealized critical discussion. What we saw was that, from the perspective of the rules of criminal procedure, the discussion in this case was correct with respect to the way in which the District Court defended its decision. From the perspective of a fair trial and from the perspective of a rational discussion, however, several points of critique can be given.

The first point of critique concerns the quality of the argumenta-tion of the District Court with respect to the statements of the therapist. As we have seen, the argumentation with respect to these statements is based on a common-sense presumption which remains implicit and which can be criticized in various respects. Therefore, the anchor for the evidence which supports the main part of the argumentation of the District Court turns out to be too weak to consider these facts as proven beyond reasonable doubt. As a consequence, we are justified to have our doubts about the quality of the argumentation with respect to the ‘manner of death’ of the District Court from the perspective of a rational discussion. From the perspective of a rational discussion which formulates norms which can be considered as a methodological maximum, a relevant ideal norm for a rational justification of a decision about the evidence in a criminal process could be that, if asked to do so, a judge is obliged to specify the grounds on which his belief in the testimony of an expert witness is based. Such an obligation would be required especially if, as in the ball-point case, the decision rests for the main part on this testimony. In this way, the decision about the evidence could be criticized by the parties and other judges with respect to the quality of the evidence.

The second point of critique concerns the fact that the District Court did not explicitly reject alternative explanations of the death of Mrs. de M. From the perspective of a rational discussion, we could criticize the decision of the District Court because of the fact that it did not give insight into the considerations for rejecting alternative explanations of the death of the mother. Because the District Court did not react to adequately ‘anchored’ counter-arguments, the decision does not meet the requirements of a rational discussion. From the perspective of a rational discussion, a relevant ideal norm could be that, if the defense presents a relevant alternative view on the case which could be in favour of the accused, the judge has an obligation to explain why he thinks this alternative view less probable than the view presented by the prosecution.

I have shown how the pragma-dialectical theory, ideas developed by Anderson and Twining and norms developed by Wagenaar van Koppen and Crombag can be connected in the analysis and evaluation of argumentation in criminal cases and how the argumentation in a concrete case can be criticized from the perspective of a rational discussion.

NOTES

i. See Henket (1997), Kaptein (1997), Nijboer (1997).

ii. See for example Wagenaar et al. (1993), MacCormick and Summers (1991:21-23).

iii. A pragma-dialectical perspective on the legal process starts from what lawyers call a ‘party model’ of the Dutch criminal process. Such a model differs from one in which the judge acts as an independent investigator looking for the truth, independent of what the parties say.

iv. For an extensive description of the various forms of argumentation see van Eemeren and Grootendorst (1992 chapter 7).

v. See Plug (1994,1995,1996) for a more extensive description of the various forms of complex argumentation in law.

vi. In my analysis I reconstruct the various components of the criminal offense as separate arguments.

vii. For a more extensive treatment of the subject of missing premises see Van Eemeren and Grootendorst (1982:60-72).

viii. For a logical analysis of the contra-argumentation for the fact that J.T. cannot have killed his mother see Kaptein (1997:60-61).

ix. See the pragma-dialectical rules 11 and 12 formulated by Van Eemeren and Grootendorst (1984:170-171).

x. See Van Eemeren and Grootendorst (1992:209).

xi. For a discussion of other types of argumentation schemes in legal argumentation See Feteris (1997b), Jansen (1996,1997), Kloosterhuis (1994,1995,1996).

xii. Note that the arguments 9 and 13 are used to defend 4 as well as 5.

xiii. See for a more extensive treatment of argumentation schemes Van Eemeren and Grootendorst (1992:94-102).

xiv. For a description of the fallaciousness of circular reasoning see Van Eemeren and Grootendorst (1982:153-157).

xv. From empirical research by, among others, Loftus (1979) we know that witnesses often tell stories which are not only based on what they have observed, but also on inferences about what happened, and on transformations which make the recollection more consistent and more understandable. According to Merckelbach and Crombag (1997:314 ff) during the retention stage, memories change: (a) a witness can forget what he has observed, (b) he can add information from another source – post hoc information – to his memory, and (c) he can exchange parts of his own observation with information from another source. Therefore, recovered memories cannot be trusted completely for their truth.

xvi. These ideas on common-sense presumptions as background generalizations are based on ideas developed by Cohen (1977:247), who says that so-called ‘common-sense presumptions’ state what is normally to be expected. However, they are rebuttable in their application to a situation if it can be shown to be abnormal in some relevant respect.

REFERENCES

T. Anderson, W. Twining (1991). Analysis of evidence. Boston and London: Butterworths.

L.J. Cohen (1977). The probable and the provable. Oxford: Clarendon.

L.J. Cohen (1989). Memory in the real world. Hove: Erlbaum.

F.H. van Eemeren, R. Grootendorst (1992). Argumentation, Communication, and Fallacies. New York: Erlbaum.

Eemeren, F.H. van, E.T. Feteris, R. Grootendorst, T. van Haaften, W. den Harder, H. Kloosterhuis, T. Kruiger, J. Plug (1996). Argumenteren voor juristen. Het analyseren en schrijven van juridische betogen en beleidsteksten. (Argumentation for lawyers) (third edition, first edition 1987) Groningen: Wolters-Noordhoff.

Eemeren, F.H. van, R. Grootendorst (1992). Argumentation, communication, and fallacies. A pragma-dialectical perspective. Hillsdale NJ: Erlbaum.

Feteris, E.T. (1987) ‘The dialectical role of the judge in a Dutch legal process’. In: J.W. Wenzel (ed.), Argument and critical practices. Proceedings of the fifth SCA/AFA conference on argumentation. Annandale (VA): Speech Communication Association, pp. 335-339.

Feteris, E.T. (1989). Discussieregels in het recht. Een pragma-dialectische analyse van het burgerlijk proces en het strafproces. Dordrecht: Foris.

Feteris, E.T. (1990). ‘Conditions and rules for rational discussion in a legal process: A pragma-dialectical perspective’. Argumentation and Advocacy. Journal of the American Forensic Association. Vol. 26, No. 3, pp. 108-117.

Feteris, E.T. (1991). ‘Normative reconstruction of legal discussions’. Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Argumentation, June 19-22 1990. Amsterdam: SICSAT, pp. 768-775.

Feteris, E.T. (1993a). ‘The judge as a critical antagonist in a legal process: a pragma-dialectical perspective’. In: R.E. McKerrow (ed.), Argument and the Postmodern Challenge. Proceedings of the eighth SCA/AFA Conference on argumentation. Annandale: Speech Communication Association, pp. 476-480.

Feteris, E.T. (1993b). ‘Rationality in legal discussions: A pragma-dialectical perspective’. Informal Logic, Vol. XV, No. 3, pp. 179-188.

Feteris, E.T. (1994a). ‘Recent developments in legal argumentation theory: dialectical approaches to legal argumentation’. International Journal for the Semiotics of Law, Vol. VII, no. 20, pp. 134-153.

Feteris, E.T. (1994b). Redelijkheid in juridische argumentatie. Een overzicht van theorieën over het rechtvaardigen van juridische beslissingen. Zwolle: Tjeenk Willink.

Feteris, E.T. (1995). ‘The analysis and evaluation of legal argumentation from a pragma-dialectical perspective’. In: F.H. van Eemeren, R. Grootendorst, J.A. Blair, Ch.A. Willard (eds.), Proceedings of the Third ISSA Conference on Argumentation, Vol. IV, pp. 42-51.

Feteris, E.T. (1997a). ‘The analysis and evaluation of argumentation in Dutch criminal proceedings from a pragma-dialectical perspective’. In: J.F. Nijboer and J.M. Reijntjes (eds.), Proceedings of the First World Conference on New Trends in Criminal Investigation and Evidence, Lelystad: Koninklijke Vermande, p. 57-62.

Feteris, E.T. (1997b). ‘De deugdelijkheid van pragmatische argumentatie: heiligt het doel de middelen?. In: E.T. Feteris, H. Kloosterhuis, H.J. Plug, J.A. Pontier (eds.), Op goede gronden. Bijdragen aan het Tweede Symposium Juridische Argumentatie. Nijmegen: Ars Aequi, pp. 98-107.

M.M. Henket (1997). ‘Omgaan met de feiten. Opmerkingen naar aanleiding van de Leidse Balpenzaak’. In: E.T. Feteris, H. Kloosterhuis, H.J. Plug, J.A. Pontier (eds.), Op goede gronden. Bijdragen aan het Tweede Symposium Juridische Argumentatie. Nijmegen: Ars Aequi, pp. 50-55.

H. Jansen (1996), ‘De beoordeling van a contrario-argumentatie in pragma-dialectisch perspectief’. In: Tijdschrift voor Taalbeheersing, jrg. 18, nr. 3, pp. 240-255.

H. Jansen (1997). ‘Voorwaarden voor aanvaardbare a contrario-argumentatie’. In: E.T. Feteris, H. Kloosterhuis, H.J. Plug, J.A. Pontier (eds.), Op goede gronden. Bijdragen aan het Tweede Symposium Juridische Argumentatie. Nijmegen: Ars Aequi, pp. 123-131.

H.J.R. Kaptein (1997). ‘Pennen als dodelijke wapens? Over criminele klok- en klepelkunde en een (logische?) kloof tussen feiten en recht. In: In: E.T. Feteris, H. Kloosterhuis, H.J. Plug, J.A. Pontier (eds.), Op goede gronden. Bijdragen aan het Tweede Symposium Juridische Argumentatie. Nijmegen: Ars Aequi, pp. 56-63.

Kloosterhuis, H. (1994). ‘Analysing analogy argumentation in judicial decisions’. In: F.H. van Eemeren and R. Grootendorst (eds.), Studies in pragma-dialectics. Amsterdam: Sic Sat, p. 238-246.

Kloosterhuis, H. (1995). ‘The study of analogy argumentation in law: four pragma-dialectical starting points’. In: F.H. van Eemeren, R. Grootendorst, J.A. Blair, Ch.A. Willard (eds.), Proceedings of the Third ISSA Conference on Argumentation. Special Fields and Cases, Amsterdam: Sic Sat, p. 138-145.

Kloosterhuis, H. (1996). ‘The normative reconstruction of analogy argumentation in judicial decisions: a pragma-dialectical perspective’. In: D.M. Gabbay, H.J. Ohlbach (eds.), Proceedings of the International Conference on Formal and Applied Practical Reasoning. Berlijn: Springer, p. 375-383.

P.J. van Koppen, D.J. Hessing, H.F.M. Crombag (1997). Het hart van de zaak. Psychologie van het recht. Deventer: Gouda Quint.

E.F. Loftus (1979). Eyetwitness testimony. Cambridge, M.A.: Harvard University Press.

H.L.G.J. Merckelbach, H.F.M. Crombag (1997). ‘Hervonden herinneringen’. In: P.J. van Koppen, D.J. Hessing, H.F.M. Crombag (eds.), Het hart van de zaak. Psychologie van het recht. Deventer: Gouda Quint, pp. 334-352.

J.F. Nijboer (1997). ‘Over een balpen en een voorbeeldige voetballer’. In: E.T. Feteris, H. Kloosterhuis, J. Plug, H. Pontier (eds.), Op goede gronden. Bijdragen aan het tweede symposium juridische argumentatie, Rotterdam 14 juni 1996, pp.64-70.

N. MacCormick en R. Summers (1991). Interpreting statutes. Aldershot etc.: Dartmouth.

Plug, H.J. (1994). ‘Reconstructing complex argumentation in judicial decisions’. In: F.H. van Eemeren and R. Grootendorst (eds.), Studies in pragma-dialectics. Amsterdam: Sic Sat, p.246-255.

Plug, H.J. (1995). ‘The rational reconstruction of additional considerations in judicial decisions’. In: F.H. van Eemeren, R. Grootendorst, J.A. Blair, Ch.A. Willard (eds.), Proceedings of the Third ISSA Conference on Argumentation. Special Fields and Cases, Amsterdam: Sic Sat, p. 61-72.

Plug, H.J. (1996) ‘Complex argumentation in judicial decisions. Analysing conflicting arguments’. In: D.M. Gabbay, H.J. Ohlbach (eds.), Proceedings of the International Conference on Formal and Applied Practical Reasoning. Berlijn: Springer, p. 464-479.

D.A. Schum (1994). The evidential foundations of probabilistic reasoning. New York etc.: John Wiley & sons.

W. Twining (1994). Rethinking evidence. (first edition 1990). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wagenaar, W.A., P.J. van Koppen, H.F.M. Crombag (1993). Anchored narratives. The psychology of criminal evidence. London: Harvester Wheatsheaf.