ISSA Proceedings 2002 – Argument Density And Argument Diversity In The Licence Applications Of French Provincial Printers, 1669 – 1781

In this pilot project we survey the kinds of argumentation used by the men and women in provincial France who applied for royal licences to run printing houses in the ninety- year period, 1669 – 1781.

In this pilot project we survey the kinds of argumentation used by the men and women in provincial France who applied for royal licences to run printing houses in the ninety- year period, 1669 – 1781.

At the end of the ancien régime in France the appointment or licensing of a printer was a complex process that involved input from a number of high officials in the royal government as well as from local officials in the town the printer was to work. In 1780, for example, the appointment of printer in Dijon involved the Keeper of the Seals, the Director of the Book trade, the Intendant, the Lieutenant of police and the Inspector of the Book trade as well as the officers and other members of the printers’ guild in Dijon(i).These men were all following elaborate rules for printer appointment laid out in detail by royal decree in 1777. These procedures represented the mature development of the French Crown’s century-long determination to license – and consequently decide – who would hold the 310 printer positions in the realm(ii).

Licensing began in 1667 when Colbert banned all new printers from setting up businesses without special approval(iii). In the years following 1667 some printers in some towns saw great advantages (notably increased market share) to be gained from the royal licensing policies and moved to see that the ban was implemented(iv). In other towns the licensing requirement went unnoticed until 1704 when Crown officials set quotas on the numbers of printers allowed in each town and charged the Lieutenants of police with seeing that they were respected. In the subsequent decades (and not without resistance) the number of printers was forcibly reduced. By 1739 – when the rules were tightened and the number of printers was again reduced – there was wide acceptance of printer licensing. In 1759 the numbers were further reduced and in 1777 the procedures for printer appointment were clarified.

At the end of the ancien régime there seems to have been considerable agreement between the candidates, the guild officials, and the royal officials, on what constituted a good printer. On the one hand, they were all thinking to some extent in terms of guild entrance requirements that could be found in different statutes in the seventeenth century, and these were stated in an important 1723 decree that governed Parisian printers and was then extended in 1744 to the rest of the realm(v). At the core of this understanding were the following requirements: four years of apprenticeship were needed and three consecutive years as a journeyman. Candidates had to be twenty years of age, know Latin and be able to read Greek, and produce a certificate from the rector of the university to this effect. Sons of masters were exempt from apprenticeship and journeyman requirements. All candidates including sons of printers had to submit to an examination before the guild officers.

These requirements were understood by everyone but satisfying only these was not sufficient to obtain a printer position in eighteenth-century France. Candidates covered all the required bases in their applications and added yet more evidence of suitability. Defay, our Dijon example from 1780, was a son of a printer and, although he did not need to complete a stint as a journeyman, he made it clear that he had vast experience directing a printing house. Also, he had his curé produce a certificate saying that he was a man of probity. The Lieutenant of police in Dijon in his letters made two points about Defay: he had been in printing all his life, and his conduct was irreproachable. Given the heightened fears of the clandestine book trade in the reign of Louis XVI, it is unlikely that this last comment meant anything but that he could be deemed loyal and reliable.

This understanding of what made for a good printer in the reign of Louis XVI (1774-1792) was not firmly fixed in the earlier reign of Louis XIV (1643-1715). The hypothesis of our present essay is that, in the minds of the applicants, the conception of what constituted ‘a good printer’ was forged over the course of the eighteenth century, especially in the early years. The evidence we will consider for our hypothesis is the changing patterns of argumentation recorded in samples of the licensing decrees from 1669 – 1781.

The Data

The documents we are studying are decrees (arrêts) issued by the King’s Council. They contain summaries of the arguments which were made in the application letters for printer positions. The application a printer made for a licence would have taken the form of a letter (applicant letter) written by him or his lawyer and sent to the chancellor or Keeper of the Seals together with supporting letters from other sources in aid of the application. With few exceptions, these original applicant letters have not survived(vi). What remains are summaries of the arguments in the applicant letters that were placed in the preamble to the decrees issued by the King announcing the decision on the application, i.e., whether to grant a licence, to recommend further investigation, or to deny a licence. These decrees, which took the form of Privy Council arrêts, survive in the archives of the Privy Council in the archives nationales (V6). The summaries in the decrees were made by Masters of Request in the Chancellor’s office or, after 1701, members of the bureau de la librairie. We will assume that the summaries of the arguments in the decrees closely resembled the original arguments given by the applicants in support of their petitions.

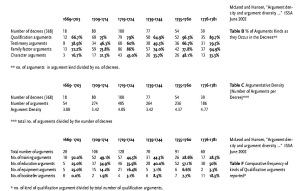

At the current stage of our research, our data presents us with certain problems which weaken the strength of our conclusions. For example, for the earliest period we sample, 1669-1703, we have only eighteen decrees to work with; a sample too small for a solid basis. We are more confident of our sampling in the periods 1709 -1714 and 1719-1724, where we have 80 and 100 decrees respectively to work with; for 1739 – 1744 we have 77 decrees, and 1755 – 1760 where we have 54 decrees, and the last period, 1776 – 1781 we have 39 decrees to examine. With our concern about the differences in the sample sizes from the different periods freely admitted, we are interested in seeing what patterns the data, such as it is, suggests about the thinking of printers and would-be printers in provincial France in the ancien regime.

Argumentation Theory

Hypothesizing that the printers of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century France were competing for licences in what they perceived to be a reasonably lucrative industry, gives us reason to view their petitions as earnest attempts at persuading the licence grantor to look favourably upon them. Persuasion then, is what they were up to: persuasion by any means that could be committed to paper and thought to have a chance of succeeding. Thus, in examining the decrees which have recorded these petitions, we are not surprised to find that they contain reasons why the applicant should be given a licence; i.e., they contain arguments in favour of the applicant’s petition. These were arguments given by educated urban elites of eighteenth-century provincial towns to royal officials in Versailles. One must assume (a) that the arguers had ideas about what kinds of arguments would have the best chance of success with the authorities, and (b) that they considered the arguments they gave as being relevant to their cause.

All this talk of arguments gives the historian – who has an interest in matters historical – occasion to engage the argumentation theorist – who has an interest in argumentation. Argumentation theory is simply the theory which takes an interest in arguments qua arguments.

It would be better, of course, to speak about argumentation theories, in the plural, for there are different ones with different aims, each with its own peculiar resources. Fully developed, an argumentation theory offers guidance on analysis, construction and evaluation of good arguments. But the idea of a ‘good argument’ may be viewed from different perspectives. Rhetorical theories of argumentation, like Chaim Perelman’s, focus on argument as the intermediate object between arguer and audience, and develop the importance of adapting arguments to audiences. Dialectical theories of argumentation, like that of van Eemeren and Grootendorst, turn on the rational resolution of disagreements between arguers; for them, arguments are moments in argumentation, and they offer a sophisticated model whereby argumentation can be evaluated as more or less rational. Theories mainly concerned with the evaluation of arguments – where ‘argument’ is understood as a combination of premises and a conclusion – are logical theories of argumentation. One such notable theory, developed in the last twenty-five years, is the informal logic of the Canadians Johnson and Blair(vii). In their view the standards for good arguments have not been sufficiently captured by formal logics and they attempt an enriched analysis of ‘good argument.’

All three of these theories – the rhetorical, the dialectical and the logical – share an interest in the nature of argument where that term is simply understood as a claim (conclusion) supported by reasons (premises). Arguments are the kinds of things that can be good or bad, strong or weak, depending on the degree to which they provide support for their conclusions. Hence, argumentation theorists are mainly interested in normative issues, questions of developing standards whereby to measure the goodness of given arguments.

In this essay, however, we are not concerned to evaluate arguments or argumentation found in the applicant letters, nor are we especially concerned with disagreements and objections. (We postpone these issues to a sequel.) In this preliminary study we want only to look at arguments from a non-evaluative point of view and identify which kinds of arguments the applicants chose as most likely to bring them success. In other words, our enterprise is descriptive and not normative, it belongs to social science and not to logic. Simply put, we wonder whether the kinds of arguments used in the applicant letters changed over the years. To answer this question we must find some way to classify arguments and look for changes in class membership. Hence, the categories of which we are in need, are categories of arguments.

The arguments we are studying may all be seen as having been meant to support the claim that the crown should grant applicant X a printer’s licence to practice in provincial city Y. We find that the kinds of reasons (premises) brought forward to support this conclusion may be divided into four broad categories, and accordingly, there are four broad kinds of arguments that were given in support of the applications. Each kind of premise then, together with the general conclusion we indicated, gives rise to four general kinds of arguments as follows:

1. Qualification based arguments are those whose premises make reference to an applicant’s qualifications: that he is properly trained, has the relevant education, and has the equipment needed to be a printer.

2. Character arguments are those whose premises make reference to the candidate having a good moral character and/or of his loyalty to the state.

3. Family factor arguments are those whose premises show that the applicant had some kind of a claim on the position due to the fact that he or she had a relative (father, or father-in-law) in the printing business. Included here will also be arguments turning on sympathy to the effect that the applicant and his family would fall on hard times if their application was unsuccessful.

4. Testimony arguments are those whose premises make reference to the qualifications of the applicant. They refer to supporting letters from colleagues, employers, and/or church or government officials.

A First Look at the Data

A First Look at the Data

Our first observation concerns the diversity of kinds of arguments used by an applicant. We assume that each decree reports more or less correctly the arguments that were contained in the original application letter.We now ask, did all the candidates use all four kinds of arguments? (e.g., family factor argument, character argument, etc.) And the answer is No. Not all the applicants availed themselves of all of the four kinds of arguments. Nevertheless, as Table B indicates, there is, in the six periods we studied, a steady increase in the argument diversity of the applications. Whereas, for the years 1669-1703, we see that 12 of the 18 applicants (66.7%) made use of qualification arguments, less than 20% made use of character arguments. However, for the final period, 1776-1781, nearly all the applicants made use of qualification arguments and a third of them employed character arguments as well. Therefore, the diversity of the kinds of arguments used in the later period is greater than in the earlier period; argument diversity was on the rise.

How is this to be explained? The increase in argument diversity suggests that the candidates were increasingly aware that they had to employ different kinds of arguments in their applications; that they had to include different kinds of factors to show their eligibility. They felt that officials needed to know about their qualifications, their families and the local officials who supported them. In part this could reflect the increased competition for the limited number of printer positions as well as an understanding among both printers and officials that a certain number of bases needed to be covered.

Another tendency shown in Table B deserves to be remarked upon. Character arguments increased. In the early period only 16% used character arguments, in the second half of the 18th c. between 33% and 48% did. This is evidence that the applicants took character to be an increasingly significant factor in a successful application and that were increasingly concerned to reassure officials that they would not engage in the clandestine trade.

Another tendency shown in Table B deserves to be remarked upon. Character arguments increased. In the early period only 16% used character arguments, in the second half of the 18th c. between 33% and 48% did. This is evidence that the applicants took character to be an increasingly significant factor in a successful application and that were increasingly concerned to reassure officials that they would not engage in the clandestine trade.

A second observation concerns a relationship between arguments and application letters. We refer to this relationship as argumentative density. An application which contains more arguments than another application has greater argumentative density (on the assumption that all the applications were of roughly equal length). Argumentative density is calculated (i) for a document (a decree) by simply counting the number of arguments it contains, and (ii) for a period (a set of documents) by dividing the total number of arguments in the period by the number of decrees in the period.

Table C shows an increase in argumentative density in the decrees over the period of our study. So, whereas the average application contained 3.00 arguments in the earliest period, this rose to 3.42 in 1709-14, then to 4.05 in 1719-24, and then 3.42 in 1739-44, to 4.37 in 1755-60, and in the final period it rose to 4.77

Since we have divided the kinds of arguments given into only four kinds, once argumentative density rises over 4.0, it must be the case that for at least one of the four kinds of arguments, the applicants were offering more than one argument; that is, in some of the decrees there would be two or more arguments in favour of qualifications, for example.

The explanation of the increase in argumentation density supplements the explanation of the increase in argument diversity: applicants were strengthening their cases by increasing the number of arguments within a given kind in an application. What factors might have occasioned this change? The applicants may have felt themselves in competition with others who were also writing applications rich in argument diversity. Increased argumentation density was a means of strengthening applications which were already thought to be sufficiently diverse in argumentation. Another possibility is that over time, with the standards for printers being revised and made public by the crown, the way to ensure that an applicant was seen by the authorities as satisfying the standards, was to show that he was in some sense ‘overqualified’; that is, he had several testimony arguments in his support, one from the judicial officer, another from a clergy man, another from a guild official. This approach of showing that one met the standards ‘and then some’, led to increased argumentation density.

Looking More Closely at Qualification Arguments (Table F)

Each of the four broad categories of arguments we have identified, may be further divided into subcategories, thereby giving us a more detailed look at the kind of arguments that were employed. In the broad category of qualification arguments we found five different kinds of reasons or arguments. There were (a) those arguments whose premises made reference to the technical training of the applicant, that he had finished his apprenticeship or was a journeyman; (b) those arguments which reported the applicant’s formal education, especially that he had Greek and/or Latin; (c) those arguments giving as a reason that the applicant owned or had access to printing equipment; (d) those arguments which said the applicant already had a licence as a bookseller (indicating that he had successfully been through the licensing process once already).

It is striking that, in the earliest period, arguments about the applicant’s training counted for half the arguments given and education was only half as important as training. However, when we come to the last period, things were reversed. By 1776-1781 it was education which was cited as an argument most often (50%) and training had fallen to less than 30%.

This suggests that printers focussed more on convincing officials that they were educated, knew Latin and Greek, than they did on drawing attention to their training. The other discernable pattern is that having one’s own equipment decreased as a cited reason, from 25% in the early period to only 3.3% in the last period. A possible explanation for both trends is that more and more applicants were from printing families and their training and equipment were assumed.

Family Factor Arguments

There seem to be six different sub-categories of family factor arguments given in support of the printers’ applications. First, (a) there are those which identified the applicant as a son, son-in-law, nephew or grandson of a printer; (b) there are those which identified the applicant as having married a printer’s widow (and who wanted to enter the trade by taking over her printing house); then there are (c) those arguments which turned on the applicant’s father’s reputation, making reference to the father’s prudence and/or technical competence as a printer. There are also those arguments (d) wherein the applicant claimed to have been trained in a printing family from an early age, and (e) those in which the applicant declared that his family had been in the printing business for many generations. Finally, some gave (f) the ad misericordiam argument (appeal to pity, or sympathy) that the family would suffer hardships unless it was granted a printing licence.

Table E shows that the percentage of the candidates arguing that they were replacing a close relative (son replacing father, or nephew replacing uncle, etc.) increased over the period of the study. Whereas only 55.5% made this argument in the first period, 87.2% made this argument in the last period. This suggests that the printing trade was becoming increasingly closed to outsiders throughout the century. One notices also, in Table E, that there was a steady decrease in the use of ad misericordiam arguments (from 16% to 0%): this may be evidence that the printers and would-be printers refrained from making appeals to sympathy, possibly because government officials were not responsive to them. Many officials believed that poor printers were especially likely to engage in the clandestine trade and consequently should not be allowed to work. Those who thought along these lines would certainly not have responded favourably to appeals to sympathy and gradually the printers may have learned not to use them.

Some conclusions

The counting and classifying of arguments can take a number of different forms but today we would like to take up four trends in this data and suggest possible conclusions that might be of interest to historians of eighteenth-century France.

The first concerns the decline in the role of patronage in eighteenth-century society(viii). Printers were covering an agreed upon set of requirements to become a printer and there was consensus about what such a minimal set of requirements looked like. Increasingly over the course of the century, they added to this with as many additional arguments as they could. Even if, behind the scenes, patronage determined some of the licences granted, this conception of a good printer had to be addressed. There were limits on traditional patronage by the end of the eighteenth-century because the pool of possible candidates was limited and governors, bishops and other noble protectors had to limit their patronage to candidates who were able to demonstrate they could meet the requirements. The argumentation in the applications at the end of the century could then be said to reflect developing bureaucratic or administrative control which parallelled, complemented and transformed older patronage practices.

The whole licensing process suggests that the printer guilds played a smaller role in deciding who was to have a licence than they did in the seventeenth century. The guilds no longer decided who would be admitted as printers. Instead they contributed an opinion to an applicant’s dossier. That the printer guilds saw their role so reduced is possibly of interest to historians of de Tocqueville, corporations and absolute monarchy. Many historians have shown how misguided it would be to use the corporate idiom of guilds as a tool to describe the real world of eighteenth-century artisans(ix). For most artisans, there was an enormous gulf between guild rhetoric and the realities of the workplace. Our study shows that not only did guild rhetoric camouflage employer-worker relations, it also camouflaged recruitment decision making. In the case of printers, the guild rhetoric was especially hollow and when it was used, it was really a desperate effort to cling to vision of guild autonomy that no one really believed in anymore. The guild rhetoric was in fact evolving and disappearing and terms such as l’administration, concours, book trade inspectors began to fill the guild registers. The conclusion here is quite in line with de Tocqueville in that the corporate power of the printer guilds was quite clearly undermined by the monarchy.

The declining influence of the guilds did not mean, however, that the families in the printing trades did not benefit enormously as did other members of provincial urban elites from the growth of absolute monarchy. We need here only to look at the important place of the family in this argumentation and note how it increased over the course of the eighteenth century. Despite a number of indications that some philosophes and some printer workers were trying to separate the notions of “family” and “merit” in people’s thinking, it seems here that both officials and candidates increasingly fused the ideas of family and merit and did so to a greater degree, as the century wore on(x). Through the licensing process, printers and officials seem to have communicated back and forth on the issues, both sides increasingly believing that the best possible education for a printer was to have been raised in a printing family. This tendency increased over the century. This view of education gave enhanced importance to family training, both in values and in technical matters. Clearly it seems there is a consensus that candidates had to be able to make a family argument in their favour. That technical merit was not mentioned as much was largely because it was taken for granted. What mattered was something closer to ideological suitability and financial security, both important criteria for good printers and both more likely to be found in long-serving printing families.

It is clear from this data that character arguments take on more importance in the later eighteenth century than it did in the seventeenth century. Printers made reassuring claims about probity, good morals, reproachless conduct in their applications because they were countering notions that circulated in Versailles and elsewhere that printers in the provinces were heavily engaged in the selling of pirated and prohibited books. Printers and officials both were aware of the view that the printing world in the French provinces was disordered and dangerous. This persistent discourse of disorder and the numerous appeals to fear made by the printers themselves (ad baculum arguments) are evident in all aspects of book trade regulation in eighteenth-century France.

The emergence and power of this notion of dangerous disorder in the printing trades was the result, in a very large part, of the lobbying efforts of the Paris publishing industry which was concerned to protect its copyrights and markets. It was reinforced by the licensed printers in the provincial towns themselves who tried to hold on to their own market share by scaring the government with dire scenarios that would develop if officials were to be foolish enough to license more printers. These economic agendas are important in fostering a vision of the provincial countryside as one full of pirated and clandestine books, a place that had to be cleaned up if the monarchy was to survive. Some historians, such as Robert Darnton believe that this vision was close to the reality.

Whether there really was a dangerous increase in the sale of clandestine pamphlets and books, or just an exaggerated vision created by lobbyists, there is no doubt that the vision was clearly in the minds of royal officials. In the eighteenth century, royal officials believed that printers, printing and public opinion represented a much more serious danger than Colbert and his contemporaries believed they did. The arguments studied here reveal a group of printer candidates that was very concerned to present itself as ideologically acceptable. Their thinking suggests that a modern notion of ideological control had emerged, a notion that both officials and the printers shared and one that both groups (printers and officials) played a part in creating. In 1667 the ability of the French book trade to compete with the Dutch was foremost in Colbert’s thinking. This concern had not disappeared, but it was certainly being overshadowed by family and ideological considerations.

NOTES

[i] Archives nationales, (AN) V6 1099, 18 December 1780; Bibliothèque municipale de Dijon, Mss. 745, Communauté des imprimeurs-libraires de Dijon: registre des déliberations ( 10 mai 1772-22 février 1790). For references to the historical literature and the regulation of the book trade in eighteenth-century France see Jane McLeod, “Provincial book trade inspectors in eighteenth-century France,” French History 12 (1998) 127-48.

[ii] In 1701 there were 411 pinters in France (including Paris). In 1704 the ceiling ordered was 285 printers and the ceiling in 1739 was 250. In 1764 there were 309 printers and in 1777 there were 310. Census data in 1701, 1764 and 1777 is from Roger Chartier, “L’imprimerie en France” Revue française d’histoire du livre (1973) 253-279. The ceilings fixed by the Crown are from arrêts du conseil 21 July 1704 and 31 July 1739, copies in Saugrain, Code de la librairie et imprimerie de Paris (Paris, 1744, reprinted by Gregg International publishers).

[iii] The 1667 ban was reiterated in an arrêt dated 6 December 1700 which stated that the King had been informed of the contraventions committed in enforcing the rules of the book trade and that the abuses arose principally because of the large number of booksellers and printers who, without the required abilities, were setting up in several towns in the realm and were printing all sorts of books that undermined good order.

[iv] In theory this was by obtaining royal permission which was provided in the form of an arrêt du conseil, usually of the conseil privé. The requirement of an arrêt was reiterated in 1673 and 1700 and in many subsequent arrêts. By 1700 many printers were in fact obtaining them. Indispensable for understanding Privy Council decrees is Albert Hamscher. The Conseil Privé and the Parlements in the Age of Louis XIV: A Study in French Absolutism (Philadelphia, 1987) and Michel Antoine, Le Conseil du Roi sous le règne de Louis XV, (Paris and Geneva,1970).

[v] After 1723 printers used criteria outlined in a major piece of legislation issued to govern the Paris book trade, an arrêt en commandement issued by the royal council in 1723, often referred to as the Code the la Librairie. These rules were originally designed to be issued as the more forceful Déclaration but the parlement of Paris would not agree. On the 1723 Code, see H. de la Bonninière de Beaumont, “L’administration de la librairie et la censure des livres de 1700 à1750,” Ecole nationale des chartes, 1966, manuscript thesis.

[vi] The papers of the bureau de la librairie survive for 1788-9 in AN V1 549-553.

[vii] For Perelman’s theory see his classic, La Nouvelle Rhetorique (1958) authored with Lucie Olbrechts-Tyteca, Frans van Eemeren and Rob Grootendorst first espoused their view in Speech Acts in Argumentative Discourse (1984), and Johnson and Blair have developed their approach in Logical Self-Defence, 1977.

[viii] William Beik, Absolutism and Society in Seventeenth-Century France: State Power and Provincial Aristorcracy in Languedoc. Cambridge 1985. Sharon Kettering, Patrons, Brockeers and Clients in Seventeenth- Century France. Oxford 1986.

[ix] For example, see Michael Sonenscher, “ The Sans Culottes of the Year II: Rethinking the Language of Labour in Revolutionary France” Social History, 9, 1984: 301-328.

[x] On this, see David Bien, “The army in the French enlightenment: reform, reaction and revolution,” Past and Present 85 (1979) 68-98.