ISSA Proceedings 2002 – Perelman On Causal Arguments: The Argument Of Waste

Introduction

Introduction

The main aim of this paper cannot be a detailed treatment of the concept of ”causality”. Nor can I deal with all types of causal arguments distinguished by Chaim Perelman and Lucie Olbrechts-Tyteca in their ”Nouvelle Rhétorique”(i) . Therefore, after a few more general remarks on causality (section 1) and Perelman’s treatment of causal arguments (section 2) I wish to focus on a specific causal argument within Perelman’s typology, namely, the ”Argument of Waste” (= AoW)(section 3).

1. On Causality

There is no doubt that causality is a concept of fundamental importance for all types of argumentative discourse. Without being able to deal with the complexities of this concept (for recent detailed treatments cf. e.g. Tooley 1987, Pearl 2000, Meixner 2001), I would like to consider the following features as collectively defining the everyday concept of causality (cf. also Schellens, 1985, 82f.; Kienpointner, 1992, 328ff. for a more detailed discussion):

Event A is the cause of event B if and only if

1. B regularly follows A

2. A occurs earlier than (or at the same time as) B

3. A is changeable/could be changed

4. If A would not occur, B would not occur (ceteris paribus)

If an event A fulfils criteria 1- 4, it is the ”Cause” of event B, which in turn can be called the ”Effect” of A. This definition has to be supplemented with further concepts in order to prevent a reductionist view of causality. First of all, and most of the time, there is not one and only one ”Cause A” leading to one ”Effect B”, so you have to take into account that single causes are rarely necessary AND sufficient conditions for single effects (Meixner, 2000, 219ff. provides a critical overview of theories which characterize causality as a relationship based on 1. necessary conditions or 2. necessary and sufficient conditions or 3. probability or 4. nomological regularities, respectively). Moreover, argumentative discourse often has to take into account not only the immediate cause A of effect B, but also the indirect causes A1…ⁿ of B and the indirect effects B1…ⁿ of A as elements of a longer chain or sequence of causes and effects.

Furthermore, the actions of human agents cannot be reduced to causal sequences of events (cf. Meixner, 2001, 320ff.). Even in cases where the actions of human agents cause certain reactions by other human beings quite regularly, or where human actions are motivated by similar ends quite regularly (cf. criterion 1), important differences between human actions and ”natural” causes and effects remain. Persons belonging to certain (subgroups of) cultures can choose to react in different ways following differing cultural patterns of conscious and purposeful behaviour. Moreover, they can also refrain from acting (cf. Meixner, 2001, 331ff.). It is true that these choices can be severely limited by physical, psychological and/or socio-economic constraints, but they are almost never strictly determined in the way apples, pears or oranges are determined to fall from a tree by the laws of gravitation. Furthermore, one and the same action can be motivated by differing underlying incentives (emotions, feelings, beliefs) of the agents, whose actions are neither strictly determined by each single incentive nor by all of them taken together.

Therefore, human actions can only be called ”causes and effects” in a broader sense and they have to be clearly distinguished from natural causes and effects determined by the laws of nature (cf. von Wright, 1974).

Finally, typologies of causal arguments have to take into account that argumentative discourse very often has to deal with the evaluation of certain causes and effects. This means that argumentative discourse very often does not only deal with facts and/or probabilities, but also with the evaluation of elements of causal sequences on the basis of cultural norms and values.

2. Causal Arguments

From Aristotle and Cicero onwards (cf. Aristotle, phys. II. 3, rhet. II. 23, Top. III. 1-3; Cicero, Top. 58-67), typologies of causal arguments have tried to take into account the distinctions briefly mentioned above. Perelman has chosen to distinguish the following subtypes of causal arguments (cf. Perelman/Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1969, 263ff.; 1983, 354ff.).

Perelman’s Causal Arguments:

1. Effect – Cause

2. Cause – Effect

3. Pragmatic Argument

4. Event/Deed – Consequence

5. Means – End

6. Argument of Waste (= AoW)

7. Device of Stages

8. Argument of Direction (‘slippery slope’)

9. Argument of Unlimited Development

The first two schemes (1 and 2) deal with retrospective and predictive causal argumentation in general. The Pragmatic Argument (= 3) ”permits the evaluation of an act or an event in terms of its favourable or unfavourable consequences” (Perelman/Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1969, 266; 1983, 357ff.). The fourth argument scheme concerns itself with the fact that the evaluation of causal sequences will differ considerably according to their interpretation as phenomena which are intentionally achieved by human agents or as phenomena controlled by the laws of nature (cf. Perelman/Olbrechts-Tyteca 1969, 270f.; 1983, 364ff.) and above section 1). If an effect is created intentionally, we are dealing with the fifth type of causal arguments, namely, with the means – end relation. The positive or negative evaluation of an activity as a means used for achieving a certain end differs according to hierarchies of social values and norms. An activity can be criticised as being only a means toward an end, but also praised as a good end justifies the means in achieving it.

The AoW will be described in more detail below (cf. section 3). The prototypical case of the AoW ”consists in saying that, as one has already begun a task and made sacrifices which would be wasted if the enterprise were given up, one should continue in the same direction” (Perelman/Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1969, 279; cf. also the French original: ”L’argument du gaspillage consiste à dire que, puisque l’on a déjà commencé une œuvre, accepté des sacrifices qui seraient perdus en cas de renoncement à l’entreprise, il faut poursuivre dans la même direction”; 1983, 375).

The device of stages tries to deal with the problem that the indirect effect E of an event A might be totally unacceptable for some audiences, whereas the direct effect B or intermediate effects C and D would be more acceptable. Therefore, the speaker/writer attempts to split up the pursuit of an end into several stages and to convince the audience that the first or intermediate stages might be achieved to the advantage of the audience. After that, the speaker/writer tries to convince the audience to proceed until the final stage, which at this point of time could appear in a different, more positive light or at least not be unacceptable (Perelman/Olbrechts-Tyteca 1969, 282; 1983, 379). The argument of direction, more often called ”slippery slope argument” or ”slippery slope fallacy” (cf. Walton, 1992; Walton, 1996, 96ff.), is typically used as a counter argument against the device of stages. It tells the audience: ”If you give in this time, you will have to give in a little more next time, and heaven knows where you will stop” (Perelman/Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1969, 282; 1983: 379). ”Unlimited development”, the last causal argument listed by Perelman, is a counter argument against the argument of direction: ”[…] arguments with unlimited development insist on the possibility of always going further in a certain direction without being able to foresee a limit to this direction, and this progress is accompanied by a continuous increase of value” (Perelman/Olbrechts-Tyteca 1969: 287; 1983: 387).

Apart from reproducing ancient distinctions of causal arguments Perelman has also introduced some new types which were neglected in the classical rhetorical tradition or which were only treated very briefly. Some of these ”new” causal arguments deserve further treatment even today, in spite of the fact that many weak points of Perelman’s typology have been criticized and improved in more recent typologies of causal schemes. Some of these critical remarks and the resulting improvements are listed below.

First of all, Perelman does not provide explicit versions of the schemes underlying causal arguments. From Hastings onwards, recent typologies have provided explicit reconstructions of the argument schemes involving causal relations (cf. e.g. Hastings, 1962, 56ff.; Schellens, 1985, 90ff.; Van Eemeren/Kruiger, 1987; Kienpointner, 1992, 336ff.; Walton, 1996, 67ff., 95ff.; Grennan, 1997, 165ff.; Garssen, 1997, 19f.). Moreover, most of the recent typologies provide lists of critical questions, which point out potential deficiencies of the respective causal arguments or fallacious applications of a scheme (cf. Hastings, 1962; Schellens, 1985; 1987; Van Eemeren/Kruiger, 1987; Walton, 1996; Kienpointner, 1996; Garssen, 1997). Furthermore, some of the recent studies insist on using a large sample of authentic examples from various types of argumentative discourse for the establishment and demarcation of particular schemes (cf. Hastings, 1962; Schellens, 1985; Benoit/Lindsey, 1987; Kienpointner, 1992; 1993; Warnick/Kline, 1992, and, to a lesser degree, Walton, 1996). In a similar vein, some studies try to investigate the pre-theoretical intuitions of ordinary language users in relation to argument schemes, using questionnaires concerning the classification and evaluation of short argumentative texts (cf. Hastings, 1962: 163ff.; Schellens, 1985, 231ff.) and, in a much more elaborate way, Garssen (1994; 1997, 137ff.), who uses characterizing-grouping tests and critical response tests.

Lumer (1990; 1995), too, has established a typology of some types of arguments occurring in everyday discourse, which is based on a rigorous reconstruction with techniques of formal logic. Finally, Grennan (1997, 162) deserves special mention especially because of his interesting attempt to take up suggestions made by Ehninger/Brockriede (1963) for a classification of argument schemes according to 8 types of descriptive and normative premises and conclusions.

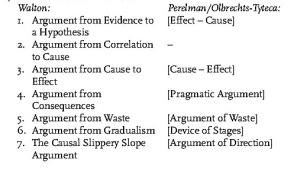

It seems to be clear that considerable improvements concerning the explicitness of presentation, the empirical foundation and the normative evaluation of argument schemes have been made. But still, Perelman’s classification of argument schemes in general and causal schemes in particular deserves praise because of the many empirically interesting types and subtypes which it contains. This does not mean that most of the causal schemes distinguished by Perelman would not also occur in recent typologies (cf. the detailed comparisons in Garssen, 1997, 34ff.). Walton (1996: 67ff.), for one, distinguishes the following types of causal arguments, which roughly correspond to the types distinguished by Perelman listed in brackets(ii):

In the following, I would like to take up the ”Argument of Waste”, which tends to be neglected in the rich literature on argument schemes and is only briefly dealt with in Walton’s (1996) typology of causal arguments.

3. The Argument of Waste

The prototypical use of the AoW has already been mentioned above (cf. section 2). Its underlying warrant could be reconstructed as follows: ”If one has begun to achieve a task E and has already accomplished stages A and B, then one should also accomplish C and D to arrive at E”.

But beyond that prototypical use, Perelman provides a long list of differing, though all in a way similar uses of the AoW (Perelman/Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1969, 279ff.; 1983, 375ff.). First of all, if certain resources A are available (prompted by forces like nature, fortune or a/the deity) which make it possible or even easy to achieve the final end B, these resources should definitively be used to accomplish B according to the AoW. Not to do so would mean to waste (easily) available ressources (Perelman/Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1983, 375f.).

The AoW cannot only be used to justify the decision to use some resource or means A, but also for rejecting the use of A. For example, if some end B is achieved only to a small extent or partially or to a large extent, but not totally, A is devalued correspondingly. Of course, the AoW evaluates a totally inefficient means A even more negatively because it could not achieve end B at all and has proved to be a useless sacrifice (Perelman/Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1983, 377).

However, if you have the opportunity to perform an act which is a unique or decisive step A towards achieving an end B, this step A is especially recommended by the AoW (Perelman/Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1983, 378). Correspondingly, the AoW strongly recommends that a superfluous act A must not be done because it is a waste of energy to perform this act in addition to the acts which are already efficient means for achieving B.

No doubt, this list can be elaborated, but it is a rich survey of the variants of the AoW occurring in everyday argumentation. And not all sub-classes given by Perelman can easily be included within the following explicit version of the AoW provided by Walton (1996, 80), which only covers the prototypical sub-class:

ARGUMENT OF WASTE:

If a stops trying to realize A now, all a’s previous efforts to realize A will be wasted.

If all a’s previous attempts to realize A are wasted, that would be a bad thing.

Therefore, a ought to continue trying to realize A.

In the following paragraphs, a small sample of about 30 instances of the AoW in everyday argumentation (e.g. in private discussions, political debates and speeches, commentaries in newspapers, consumers’ informations) will provide the basis for a modified reconstruction of its premises and conclusions. Moreover, criteria for distinguishing the AoW from similar argument schemes like the Pragmatic Argument or schemes involving ends and means will be developed. Of course, there are also many borderline cases and some of these will be presented below.

The first examples(iii) are given to illustrate the prototypical case of the AoW. The warrant of this application of the AoW could also be paraphrased with the proverb: ”In for a penny, in for a pound”. This application of the AoW justifies the continuation of a chain of causally connected actions A, B (…), where a certain amount of energy, time and/or financial resources have already been invested in order to reach a certain goal C. Correspondingly, this subtype of the AoW is also used for criticizing the non-continuation or the insufficient continuation of such a chain of actions.

For example, this variant of the AoW recommends the continuation of a professional career which has already begun or criticizes the insufficient funding of social institutions, if the funding does not allow the respective institution to go on working adequately in order to reach its expected goals. The following two passages taken from the novel ”Thinks…” by David Lodge(iv) illustrate these applications of the WoA. In the first example, the female protagonist Helen Reed, a British novelist teaching courses on creative writing at the University of Gloucester, who is the mother of two children, justifies her earlier point of view, namely, not to have children before finishing her Ph.D.:

1. Helen: ‘[…] I didn’t want a child, not when I was still on the very bottom rung of the academic ladder. But I didn’t want to have an abortion – my residual Catholic conscience, I suppose.’ (Lodge 209)

This particular instance of the AoW could be reconstructed as follows:

If a woman has started an academic career, she should not have children, but continue her career, especially if she still has a relatively low rank in the academic hierarchy.

Helen Reed has started an academic career and is still on the very bottom rung of the academic ladder.

Therefore, she should not have children and continue her academic career.

Actually, as the immediately following context shows, in this case the AoW is so to speak ”overruled” by an Argument from Authority based on the catholic background of Helen.

The male protagonist Ralph Messenger, a British cognitive scientist running the Center of Cognitive Science at the University of Gloucester, criticizes the insufficient funding of his university, which should have expanded to allow a substantial growth eventually leading to a high quality research output which could compete with that of other universities:

2. Ralph: […] The University was fashionable in the seventies, but it was never given enough money to grow to a viable size, not for serious scientific research anyway. Now it’s on the slide, to be frank. Like a football club desperately trying to avoid relegation from the Premier League. (Lodge 41)

Another variant of the prototypical case of the AoW points out that gifts and talents which have been used successfully over a long period of time in the past should be even more fully exploited to meet the challenges of the future. In a political speech delivered at the Labour Annual Conference 1997, British Prime Minister Tony Blair asks his party not to indulge in complacency after their overwhelming victory in the 1997 elections, because this was only the first step and New Labour must continue in order to reach the final goal of two full consecutive terms of office:

3. […] but . but . however still no complacency . because the first of May was the beginning not the end . we have never won two full consecutive terms of office never and that is one more record I want us to break [applause] (Tony Blair, Speech at the Labour Party Annual Conference, September 1997; Fairclough, 2000:,104; Fairclough marks short pauses with dots)

Another variant of the prototypical use of the AoW tells us that after a certain amount of energy, time, money or other political resources have been invested in the achievement of some professional or political goal, there seems to be ”no way to step back”. To continue with the ongoing series of actions is then presented almost as a necessity for the respective agents. In example 4, a political commentary portrays the Indian Prime Minister Vajpayee as having almost no other political choice than war with Pakistan, after having concentrated huge numbers of Indian troops at the Kashmir border to Pakistan for months:

4. The Indian Prime Minister massed 750,000 soldiers along the border with Pakistan in the winter. Pulling them back now, just as militant activity has been stepped up in Kashmir, would be a grave loss of face – and politically fatal. With popular support for his Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party waning, he can’t afford to be seen as backing down from a confrontation with Pakistan. (TIME, June 3, 2002, p. 66)

In a similar vein, Tony Blair argues for a continuation of the war against Yugoslavia because to stop the military engagement of NATO would have terrible consequences. This example is a borderline case, which could also be classified as an instance of the Pragmatic Argument pointing out the negative consequences of not continuing with the war. But the formulation ”now it has started” implicitly refers to the fact that NATO has invested too much money and military prestige into the campaign to step back at this stage. Additionally, all this happens while NATO is celebrating its 50th birthday, that is, during an occasion of proudly looking back on what has been collectively achieved so far (and what should not be ”wasted”):

5. Just as I believe there was no alternative to military action, now it has started I am convinced there is no alternative to continuing until we succeed. On its 50th birthday NATO must prevail. Milosevic had, I believe, convinced himself that the Alliance would crack. But I am certain that this weekend’s Summit in Washington under President Clinton’s leadership will make our unity and our absolute resolve clear for all to see. Success is the only exit strategy I am prepared to see.

(Tony Blair, Speech at the Labour Party Annual Conference, September 1997; Fairclough, 2000, 116)

Apart from the protoypical cases illustrated so far, there are other subtypes of the AoW. One of them does not so much focus on the continuation of a course of action already begun by an individual or collective agent, but rather claims that externally given goods, skills or technological facilities should actually be put to use. If the agent(s) are provided with good opportunities A for successful actions and do not use them as much and as efficiently as possible in order to reach a certain goal B this again amounts to a waste of resources.

In the first example Ralph Messenger tells Helen Reed that all his students are postgraduates because he considers teaching undergraduates as a waste of the time and energy for his staff:

6. Ralph: ‘[…] our students are all postgraduates. We don’t run undergraduate courses, much to the University’s displeasure.’

Helen: ‘Why is that?’

Ralph: ‘I don’t want my people wasting their time and energy teaching undergraduates elementary programming.’ (Lodge 46)

In the second example, Ralph is accused of being heartless by his wife Carrie because he has just told their 8-year-old daughter Hope that her grandfather, who is seriously ill from a heart attack, will not go to heaven after his death. Ralph has also told Hope that her grandfather after his eventual death will be cremated and will continue to exist only in their memories. Ralph justifies these remarks with having had to make use of a good opportunity:

7. Carrie: ‘I couldn’t believe what you were saying just now. You were talking like Daddy was already dead.’

Ralph: ‘It seemed to me a good opportunity to get Hope used to the idea of what death means.’ (Lodge 248)

A further variant of the AoW asks for making use of good opportunities A for reaching a goal B in a way which will achieve the intended goal fully (that is, in quantifiable cases, 100%). Consequently, actions are criticized if they are successful only to a small extent.

A first example, which is at the same time an illustration for a fictitious application of the AoW (cf. Quintilian, inst. orat. 5.10.95 on ”argumenta a fictione”, Fisher 1988, 82ff. on ”suppositional” arguments and Kienpointner, 1992, 242 on ”fictitious” arguments), again comes from a passage of Lodge’s novel ”Thinks…”, where Helen Reed argues that her laptop would feel bored if it was a human being because she is only able to use less than 10% of its computational capacity. In this way, she implies that she is wasting the intelligence invested in creating the processing unit of her computer:

8. Helen: ‘[…] If my Toshiba laptop were a human being it would be bored stiff because I only use it to do word-processing. I don’t suppose I use even ten per cent of its brainpower. But the computer doesn’t mind.’ (Lodge 140)

If the goal is achieved at least to a large extent (in quantifiable cases, a percentage above 50%), a person using the AoW might acknowledge that all in all, the respective course of action can still be positively evaluated. For example, if somebody buys organic food, the expectation is that the food will not contain any residues of pesticides. If the food contains pesticides, the AoW seems to tell us that the money has been wasted. However, according to an article by J.M. Horowitz in TIME, scientific analysis has shown that although this goal is not achieved 100%, it is realized at least to a large extent (73% of organic fruits and vegetables have been found to contain no pesticides). Under these circumstances, buying organic food is not rejected by Horowitz as an inefficient action by the AoW:

9. GO ORGANIC. Worried that you’re paying a premium for organic food but that it’s chockfull of chemicals anyway? Well, the first detailed scientific analysis on the subject concludes that organic fruits and vegetables contain pesticide residue, but far less often than conventional produce does (23% vs 73% of the time). (Janice M. Horowitz, TIME June 3, 2002, p. 78)

Of course, there are also borderline cases, where it is impossible to judge precisely to what degree a goal has been reached. In these cases, the AoW cannot lead to uncontroversial conclusions. The question whether a means A is used efficiently to reach the respective goal B remains open, as in the following commentary by Helen Gibson on the question whether the British royal family is worth the money paid by the taxpayers:

10. Is the royal family worth the taxpayers’ millions? They contribute to the pomp and pageantry of British heritage that fuels the nation’s $93-billion-a-year tourism industry. The financial value of their charity work and public functions, while vast, is harder to quantify. But then how much would a president cost?

(Helen Gibson, TIME June 3, 2002, p. 47)

The clearest case of ”waste”, of course, seems to occur when a course of action does not at all lead to the intended goal. In this case, the respective course of action is judged to be a useless sacrifice and is negatively evaluated by the AoW. As in the case of new technology designed to rescue Venice many years ago, which has now become obsolete because of recent insights by studies in climate change. To build these underwater gates nowadays would mean a useless waste of the respective resources, argues the Italian scientist P.A. Pirazzoli:

11. Venice is sinking […] The solution: inflatable, underwater gates that would stay out of sight at the lagoon bottom and rise up only during storms or higher-than-usual tides. […] Now it may be too late, says Italian scientist Paolo Antonio Pirazzoli, of France’s Center of Scientific Research. Two decades of studies on climate change have raised the prospect of higher sea levels than previously thought, so the gates may be obsolete shortly after they’re built. ”It doesn’t make sense to use a 20-year-old plan for a growing problem”, he says. (Barbie Nadeau, NEWSWEEK June 3, 2002, p. 8)

The same kind of argumentation is generally found whenever we are given the advice to ensure that machines, instruments and other technological facilities are constantly checked in order to prevent malfunctioning, which in turn would mean a waste of the money used for their acquisition and installation:

12. What use is a smoke alarm with dead batteries? Don’t forget it, check it.

(THE OBSERVER, 3.3. 1991, quoted after Ilie, 1994, 103)

The problem of the efficient use of invested money is constantly at stake not only at the individual level, but also at the societal level. The following two examples illustrate the use of the AoW in discussions about the efficient budget expenditure of (federations of) states. In the following passage taken from a commentary by Fareed Zakaria the author criticizes the comparatively small military budget of the EU. Beyond this argument of comparison, using the AoW, Zakaria also argues that the EU does not spend its money well and thus cannot efficiently achieve the results for which modern armies are needed at present:

13. With economies of roughly the same size ($8 trillion each), Europe spends only $140 billion on defense, compared with America’s $347 billion. Worse, Europe spends its money badly, maintaining large land armies (created to fight a Soviet invasion) rather than developing technology, logistics and strike forces, which are the needs of the present.

(Fareed Zakaria, NEWSWEEK June 3, 2002, p. 17)

In his speech to the Singapore Business Community (8 January 1996), Tony Blair argues that the ultimate goal of New Labour must be a ”stakeholder society”, that is, a nation where everybody is involved, not only a certain percentage of the population. Note that this argument at first sight could also be subsumed under the subtype of the AoW which deals with the achievement of an intended result to a certain (quantifiable) degree. However, Blair makes it quite clear that according to his point of view, this is an ”all-or-nothing” problem, so that anything less than 100% success would be a useless sacrifice, a waste of talent and economic resources:

14. The economics of the centre and the centre-left today should be geared to the creation of the stakeholder economy which involves all our people, not a privileged few, or even a better-off 30 or 40 or 50 per cent. If we fail in that, we waste talent, squander potential wealth-creating ability, and deny the basis of trust upon which a cohesive society – one nation – is built.

(Tony Blair, Speech to Singapore Business Community, 8 January 1996; Fairclough, 2000, 88)

Pessimists use this variant of the AoW to conclude that human life taken as a whole, with all the knowledge and experience accumulated by an individual from birth to death, is totally wasted, unless an eternally existing human soul or mind or spirit continues to exist after we die. Helen Reed uses this technique of reasoning in the following passage from Lodge’s novel ”Thinks…”:

15. Helen: ‘Well, it seems pointless to spend years and years acquiring knowledge, accumulating experience, trying to be good, struggling to make something of yourself, as the saying goes, if nothing of that self survives death. (Lodge, 35)

The last variants of the AoW I am going to deal with concern two extreme cases: The first subtype strongly recommends the performance of a decisive action A for reaching a goal B in one step, that is, the clever use of a unique opportunity at exactly the right time. The second subtype strongly rejects the idea of performing a superfluous action, that is, an action A which is totally unnecessary in reaching the intended goal B. The first subtype is used to recommend the ideal kind of efficient action. The second subtype serves to reject the worst kind of inefficient action, an action which not only does not reach its goal but is completely unnecessary.

Here are two examples. The first one describes Ralph’s thoughts while he is staying at Helen’s flat. She has just left it for a few minutes. On a desk, Ralph recognizes Helen’s laptop, which contains her private diary, as she has previously told him. Now he faces the following dilemma: on the one hand, it would be morally unacceptable to open the file and read the diary, but, on the other hand, it would be most interesting for a cognitive scientist like him. He persuades himself by arguing that it would be a unique opportunity (cf. also Miller, 1994 on the role of opportunity within the rhetorical discourse of technological progress):

16. Now he hesitated. It was wrong, what he was doing, very wrong. He ought to stop now, shut down the computer, close the top, go back to the sofa on the other side of the room, and wait for Helen. But he couldn’t resist the temptation. It wasn’t just personal curiosity, he told himself, it was scientific curiosity too. It was a unique opportunity to break the seal on another person’s consciousness. It was, you might say, research. (Lodge 334f.)

The second example comes from an article in NEWSWEEK informing consumers about the best up-to-date video cameras on the market. The article suggests that the very best cameras should be usable without having to study the user guide, which indeed seems to be a superfluous activity during one’s summer vacation, where normally your goal is simply to relax and to have fun:

17. These days our most important criteria are ease of use and what we might call the coolness factor; after all, who wants to lug around a thick manual and a clunky hunk of metal on his summer vacation? We rounded up six stylish cameras, left the user’s guides in their boxes and put them through their paces.

(N’Gai Croal, NEWSWEEK June 3, 2002: 66)

4. Conclusion

On the basis of the examples presented above, I would like to try to establish criteria to distinguish the AoW from other, similar kinds of argument and to formulate a general reconstruction of the AoW. Finally, I would like to make a few remarks on the critical evaluation of the AoW as a particular technique of reasoning.

The AoW, like the Pragmatic Argument and the Ends-Means-Arguments, is concerned with actions and their goals/results. Moreover, these types of causal arguments all deal with the positive or negative evaluation of these actions and their goals/results. But the AoW deals mainly with the degree of efficiency in the way in which the goals/results are achieved. When the (in)efficiency of an action is focused in argumentative discourse, we are dealing with an AoW rather than with a Pragmatic Argument or an Ends-Means-Argument.

How can we see that the efficiency of arriving at a certain goal/result is focused? Well, there are quite a few indicators which typically occur in instances of the AoW. Actually, many of them have occurred in the examples presented above. The most obvious examples are verbs like ”waste” (cf. ex. 6 and 14) and ”continue” (ex. 5). But other indicator words, phrases and sentence types are significant, too. For example, collocations like ”a good opportunity” (ex. 7), ”a unique opportunity” (ex. 16), ”only use something to do X” (ex. 8), ”to spend one’s money badly” (ex. 13), declarative sentences like ”X is the beginning, not the end” (ex. 3), ”It doesn’t make sense to use X” (ex. 11), ”It seems pointless to spend X” (ex. 15), or rhetorical questions like ”Is X worth Y?” (ex. 10), ”What use is X?” (ex. 12), ”Who wants to do X?” (ex. 17) are indicators for various subtypes of the AoW and their use as a pro argument or a counter argument.

A general version of the AoW underlying all particular instances discussed above could be reconstructed as follows:

ARGUMENT OF WASTE:

If person P wants to realise goal A, he or she should proceed in the most efficient way.

Person P wants to realise A.

Therefore, P should realise A in the most efficient way

The warrant of this reconstruction of the AoW has been formulated at a highly abstract level in order to include all context-specific variants presented above. The short characterization ”in the most efficient way” can be spelled out to include all more specific cases:

– ”If person P wants to realize goal A, he or she should continue after having begun with the realisation (because not to do so would mean a waste of P’s previous efforts)”.

– ”If person P wants to realize goal A, he or she should efficiently use available means (because not to do so would mean a waste of available resources)”.

– ”If person P wants to realize goal A, he or she should avoid means which do not lead to the intended goal at all (because not to do so would mean that P totally wastes energy and/or resources in a useless sacrifice)”.

– ”If person P wants to realize goal A, he or she should use means which are decisive for arriving at goal A (because not to so would mean to waste a particularly efficient opportunity for reaching A)”.

(etc.)

Several critical questions can test the various assumptions underlying the use of the AoW, for example (cf. Walton, 1996, 82):

Critical Questions:

Does P really want to realize A?

Are the costs for arriving at goal A less than the efforts previously made by P?

Do the available means really lead to A?

To what degree do the available means realize A?

Is it impossible that the available means realize A?

Are the available means decisive for realizing A?

Are the available means superfluous for realizing A?

Apart from these more specific questions, the AoW can be globally criticized as a type of argument because it mainly focuses on the efficiency of actions as a standard for recommending or rejecting their performance. However, this kind of reasoning neglects the fact that efficiency, or more generally, utility, is only one standard for the evaluation of actions and their goals/results (cf. Kienpointner/Kindt, 1997; Kopperschmidt, 2000). Many of the arguments presented in the examples above could be criticized because they favour a totally utilitarian and/or egoistic world view. Therefore, at least in a critical discussion based on norms for the rational resolution of conflicts, the AoW cannot be the only standard in deciding how to act, but has to be combined with other types of argument, for example, Arguments of Comparison based on the rule of justice, Arguments from Authority or causal arguments like the Pragmatic Argument, Means-Ends-Argument or the Argument of Direction.

NOTES

[i] Cf. Perelman/Olbrechts-Tyteca (1958) 1983; in the following sections of the paper, the pages and passages of this text will be quoted according to the English translation (1969), but I also will quote the pages (and in one case also the text) of the French original. It is only for the sake of brevity that I will continue to talk about ”Perelman’s typology of causal arguments”, without wanting to neglect, however, the important role of Olbrechts-Tyteca in the process of developing the New Rhetoric).

[ii] Perelman/Olbrechts-Tyteca (1969, 263; 1983, 354) shortly mention ”argumentation tending to attach two given successive events to each other by means of a causal link”, which would correspond to Walton’s ”Argument from Correlation to Cause”, but leave the examination of this type of argument to the sections on inductive reasoning.

[iii] Passages which are most relevant for the formulation of the AoW are emphasized with italic letters.

[iv] To make understanding of the dialogues taken from Lodge’s novel easier, I always add the names of the speakers.

REFERENCES

Aristoteles (1967). Physikvorlesung. Transl. by H. Wagner. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

Aristotle (1959). Rhetoric. Ed. by W. D. Ross. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Aristotle (1960). Posterior Analytics. Ed. and transl. by H. Tredennick. Topica. Ed. and transl. by E. S. Forster. London: Heinemann.

Benoit, W. L., & Lindsey, J. J. (1987). Argument Fields and Forms of Argument in Natural Language. In F. H. Van Eemeren, R. Grootendorst, J. A. Blair & Ch. A. Willard (Eds.), Argumentation: Perspectives and Approaches. (pp. 215-224) Dordrecht: Foris.

Cicero (1983). Topica. Ed. and transl. by H. G. Zekl. Hamburg: Meiner.

Eemeren, F. H. van, & Grootendorst, R. (1992). Argumentation, Communication, and Fallacies. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Eemeren, F. H. van, & T. Kruiger (1987). Identifying Argumentation Schemes. In: F. H. van Eemeren, R. Grootendorst, J. A. Blair & Ch. A. Willard (Eds.), Argumentation: Perspectives and Approaches (pp. 70-81). Dordrecht: Foris.

Eemeren, F. H. van, Grootendorst, R. & Snoeck Henkemans, F. (1996). Fundamentals of Argumentation Theory. Mahwah, N.J.: Erlbaum.

Ehninger, D. & Brockriede, W. (1963). Decision by Debate. New York: Dodd, Mead.

Fairclough, N. (2000). New Labour, New Language? London: Routledge.

Fisher, A. (1988). The Logic of Real Arguments. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Garssen, B. (1994). Recognizing Argumentation Schemes. In: F. H. van Eemeren & R. Grootendorst (Eds.): Studies in Pragma-Dialectics (pp. 105-111). Amsterdam: SicSat.

Garssen, B. (1997). Argumentatieschema’s in pragma-dialectisch perspectief. Amsterdam: IFOTT.

Grennan, W. (1997). Informal Logic. Issues and Techniques. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Hastings, A. C. (1962). A Reformulation of the Modes of Reasoning in Argumentation. Evanston, Ill. (Unpublished Dissertation).

Kienpointner, M. (1992). Alltagslogik. Stuttgart: Frommann-Holzboog.

Kienpointner, M. (1993). The Empirical Relevance of Perelman’s New Rhetoric. Argumentation, 7, 419-437.

Kienpointner, M. (1996). Vernünftig argumentieren. Reinbek: Rowohlt.

Kienpointner, M. & Kindt, W. (1997). On the Problem of Bias in Political Argumentation: An Investigation into Discussions about Political Asylum in Germany and Austria. Journal of Pragmatics, 27, 555-585.

Kopperschmidt, J. (2000). Argumentationstheorie zur Einführung. Hamburg: Junius.

Lumer, Chr. (1990). Praktische Argumentationstheorie. Braunschweig: Vieweg.

Lumer, Chr. (1995). Der theoretische Ansatz der Praktischen Argumentationstheorie. In H. Wohlrapp (Ed.): Wege der Argumentationsforschung (pp. 81-101). Stuttgart: Frommann-Holzboog.

Meixner, U. (2001). Theorie der Kausalität. Paderborn: Mentis.

Miller, C. R. (1994). Opportunity, Opportunism, and Progress: Kairos in the Rhetoric of Technology. Argumentation, 8, 81-96.

Pearl, J. (2000). Causality: Models, Reasoning, and Inference. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Perelman, Ch., & Olbrechts-Tyteca, L. (1983). Traité de l’argumentation. La nouvelle rhétorique. Bruxelles: Editions de l’université de Bruxelles (Engl. translation: The New Rhetoric. A Treatise on Argumentation. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press 1969).

Quintilianus (1970). Institutio oratoria. Ed. by M. Winterbottom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schellens, P. J. (1985). Redelijke argumenten. Utrecht.

Schellens, P. J. (1987): Types of Argument and the Critical Reader. In. F. H. van Eemeren, R. Grootendorst, J. A. Blair & Ch. A. Willard (Eds.): Argumentation: Analysis and Practices (pp. 34-41). Dordrecht: Foris.

Tooley, M. (1987): Causation. A Realist Approach. Oxford: Clarendon.

Von Wright, H. (1974). Explanation and Understanding. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press.

Walton, D. N. (1992). Slippery Slope Arguments. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Walton, D. N. (1996). Argumentation Schemes for Presumptive Reasoning. Mahwah, N.J.: Erlbaum.

Warnick, B. & Kline, S .L. (1992). The New Rhetoric’s Argument Schemes: A Rhetorical View of Practical Reasoning. Argumentation and Advocacy, 29, 1-15.