ISSA Proceedings 2010 – Argumentative Valences Of The Key-Phrase Value Creation In Corporate Reporting

« Qui donc crée de la valeur, à part les dieux? »

« Qui donc crée de la valeur, à part les dieux? »

Édouard Tétreau, Analyste. Au cœur de la folie financière (2005, p. 62)

The present paper proposes an analysis of the argumentative use of the key-phrase value creation in corporate reporting discourse, in line with Rigotti and Rocci’s theoretical model of keywords as lexical pointers to unexpressed endoxa (2005). By means of a brief quantitative analysis of concordances conducted on a corpus of full-text reports, and a detailed argumentative analysis of a relevant sample of letters to shareholders (and stakeholders), the study attempts to grasp the main patterns of pragmatic meaning and argumentative moves prompted by value creation (as one single unit of meaning) in both annual reports and corporate social responsibility reports[i]. This twofold methodological approach will enable a concomitant focus on the two main keyness criteria envisaged by Stubbs’ generic definition of keywords as “words with a special status, either because they express important evaluative social meanings, or because they play a special role in a text or text-type” (in press, p.1).

1. Value creation in economic-financial discourse

In everyday language, value is an abstract notion that denotes the degree of worth and appreciation of a certain object, depending on its desirability or utility. The relative worth of an object can also be evaluated by the amount of things (e.g. goods or money) for which it can be exchanged, and this could be considered the departure point of the conceptual journey of value in the economic and financial fields.

From a strategic management perspective (Becerra 2009), the fundamental value created by a firm is the one created for its customers through the products and services that result from the judicious management of the available resources. This value is then (at least in part) appropriated by the firm through sales revenues, entering in the process of shareholder value creation. This process is aimed to increase the wealth of the owners of the company either directly, by dividends, or indirectly, by influencing, one way or another, the price of the shares – a price that reflects the perceived value of the company on the financial market, based on all its expected future cash flows (Schauten 2010).

From a business ethics point of view, there is, however, an ongoing debate on the type of value creation that should guide the managerial decisions in corporations (Smith 2003). On the one hand, the shareholder theory considers that the main duty of the managers is to maximize shareholders’ returns, and to spend the resources of the corporation only in ways that have been authorized by the shareholders. On the other hand, the stakeholder theory stresses that “a manager’s duty is to balance the shareholders’ financial interest against the interest of other stakeholders such as employees, customers and the local community, even if it reduces shareholder returns” (p.85).

An interesting instantiation of this debate can be observed in the way in which value creation is conceived and argumentatively exploited in corporate reporting. The (financial-economic) annual reports and the corporate social responsibility reports are publications by means of which listed corporations account for their activity in front of shareholders (and stakeholders at large), in order to build trustful relationships with current and potential investors, and to legitimate themselves as responsible citizens of the world, able to “meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (World Commission on Environment and Development 1987, p. 43, in Global Reporting Initiative 2000-2006, p.2). Therefore, the present study will pay a special attention to the way in which value creation is reflected in these two types of reports, in particular in their most visible and influential narrative parts (Clarke & Murray 2000) – the introductory letters to shareholders and/or stakeholders.

2. Corpus description and methodological approach

The first phase of the study consisted of a brief computer-based analysis of a corpus of 26 financial-economic annual reports and 46 corporate social responsibility (sustainability) reports belonging to 22 listed multinational corporations. All reports referred to the financial year 2007 and were published on Internet on the websites of the respective companies[ii]. The purpose of this phase was to identify the generic pattern of pragmatic meaning of value creation in each category of reports, by means of Wordsmith Tools’ Concord analysis (considering value as search-word and creat* as context-word).

The second phase consisted of selecting from the above mentioned corpus of full-text reports, only those introductory letters (and in a limited number of cases, equivalent introductory interviews with CEOs or Presidents) that contained the key-phrase value creation. The selected documents (9 letters and 3 interviews from annual reports, and 7 letters, one introduction and 3 interviews from sustainability reports) were then argumentatively reconstructed in line with the pragma-dialectical principles (van Eemeren & Grootendorst 1999; Snoeck Henkemans 1997), in order to identify the main strategic moves in which value creation appeared. Next, a limited number of single argumentative moves were evaluated from the perspective of the Argumentum Model of Topics, in particular the taxonomy of loci (Rigotti 2008, 2006; Rigotti & Greco Morasso 2006-2010), in order to highlight the key-role of value creation (considered as one single unit of meaning) in line with Rigotti & Rocci’s model of argumentative cultural keywords (2005).

According to this model, culturally loaded words present in explicit minor premises may function, in virtue of their logical role of termini medii, as lexical pointers to shared values and beliefs (endoxa) that act as (implicit) major premises in support of certain claims. Paraphrasing Aristotle’s definition of endoxa as “opinions that are accepted by everyone or by the majority, or by the wise men (all of them or the majority, or by the most notable and illustrious of them)” (Topica 100b.21, in Rigotti 2006, p.527), Rigotti (2006) re-defines the endoxon as “an opinion that is accepted by the relevant public or by the opinion leaders of the relevant public” (p.527). Thus, a second characteristic of argumentative keywords consists in their persuasive potential – the capacity to evoke, from an (appropriately) assumed common ground, endoxa with different degrees of acceptability within certain communities.

3. Value creation in the introductory letters of the annual reports

The basic pattern of pragmatic meaning outlined by the most frequent concordances of value and creat* in the corpus of full-text annual reports shows that “Every company’s aim is to create value. To achieve this aim, decisions are taken and activities developed”. The value can be created “for the Company, for customers, and for the owners of the Company”, or “for [company’s] employees”, and generally speaking, “for all [company’s] stakeholders”. For instance “Heineken creates value and enjoyment for millions of people around the world […] through brewing”. The most frequently mentioned beneficiaries of the process of value creation are the shareholders, because “true value creation does translate into stock price appreciation”. Therefore, the possession of “a strong ability to create value in the different stages of the real estate market”, and promises such as “[our company] will create significant value from our assets in the years to come” are frequent arguments in this type of discourse aimed to win investor’s trust. As expected, various corporate resources are mentioned as material or operational base for value creation. For instance, a company may “create significant value from [its] assets”, “from eco-efficient solutions”, or “by earning higher margins” “through industry-leading performance”, and could do this “jointly with retail customers”.

Although value creation was present in almost all the annual reports of the corpus (in 22 out of 26 reports), the phrase appeared in the introductory letters of only half of them. The pattern of meaning observed in the full-text reports was also present in the letters, being included in a number of recurrent argumentative moves usually belonging to three main types of loci: the locus from final cause, the locus from efficient cause and the locus from instrumental cause.

As the main purpose of the annual reports is to attract (or keep) investors for the company, the (often implicit) standpoint of the introductory letters has the generic form: You should (continue to) invest in our company. The principal modality to support this standpoint is to show that an investment in the company can help shareholders to achieve their own ultimate goal which is to obtain good revenues from their investment (better than from other similar investment alternatives). A typical move in this direction is to highlight the good results obtained in the reporting year and to announce a (justified) optimistic outlook for the coming year, and the value created for the shareholders is the most frequent argument in this respect:

(1) “I am delighted to be able to report to you on another year of delivery of the Nestlé Model, defined as the achievement of a high level of organic growth together with a sustainable improvement in EBIT[iii] margin. […] We continue to believe that our greatest opportunity to create value for our shareholders is through further transforming our Food and Beverages business into a Nutrition, Health and Wellness offering and by improving its performance further. [The major steps in this transformation have now been made.] […] This is not to say, however, that we are not looking for other opportunities for value creation. (p.2) […] The Nestlé Model, combined with our ongoing ambitious Share Buy-Back Programme, will deliver strong earnings per share growth [in the coming year], resulting in industry-outperforming, long-term shareholder value creation.”(p. 5)

(Letter to our shareholders. Nestlé Management Report 2007: Life.)

A simplified reconstruction of this sample of pragmatic argumentation could be:

(2) (SP) (You should invest in Nestlé.)

(1) (Your goal, as a shareholder, is to have a (good) return on your investment.)

(1’) (Investing in Nestlé enables you to reach your financial goal.)

1’.1a We have created value for our shareholders in 2007.

1’.1b In 2008 we will create industry-outperforming, long-term shareholder value.

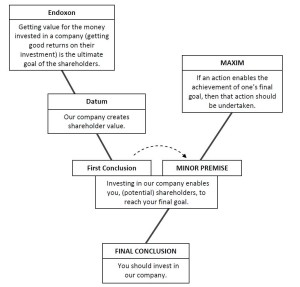

We recognize in this structure the locus from final cause (Rigotti 2008), that I represent below according to the Argumentum Model of Topics, and in which value creation has the role of terminus medius between the explicit Datum and the implicit Endoxon evoked from the context (on the left side of the Y-shaped structure):

Two other types of moves are used in the letters to shareholders in annual reports, in order to support the claim that an investment in the company would help investors to achieve their own final goal. The first type of moves regards the agency relationship between the company and its shareholders, and it is based on the locus from efficient cause. The second emphasizes the quality of the means employed by the company in order to accomplish its task, and it makes use of the locus from instrumental cause.

For instance, if we add to the argumentative structure represented in the Example no.2 the endoxon (1’.1.1’(a-b)) evoked from the corporate context by the key-phrase value creation, we can underline the fact that the value created by the company for its shareholders is a proof of the reliability of the company in relation to its shareholders:

(3) (SP) (You should invest in Nestlé.)

(1) (Your goal, as shareholders, is to have a (good) return for your investment.)

(1’) (You can rely on Nestlé in order to reach your financial goal.)

(1’.1) (We fulfil our mission towards our shareholders.)

1’.1.1a We have created value for our shareholders in 2007.

1’.1.1b In 2008 we will create industry-outperforming, long-term shareholder value.

(1’.1.1’(a-b)) (The mission of a company is to create value for its shareholders.)

(1’.1’) (An agent that fulfils its mission towards its principal is reliable.)

Based on the same locus from efficient cause, the value created for the shareholders can be an argument in support of the unique managerial capabilities of the company, given that in business, uniqueness is a source of competitive advantage:

(4) “Or, you could pick GE. (p.1) […] GE is different because we invest in the future and deliver today. […] We are a leadership company. We have built strong businesses that win in the market. (p.2)

[…] “We develop leadership businesses. […] In 2007, we demonstrated the ability to create value for our investors through capital redeployment. We sold our Plastics business because of rampant inflation in raw material costs. With that capital we acquired Vetco Gray […]. We significantly exceeded the earnings we lost from Plastics, increased our industrial growth rate, and launched new platforms for future expansion.” (p.5)

(Letter to investors. GE Annual Report 2007: Invest and Deliver Every Day.)

Textual clues indicate that the two fragments extracted from different sections of the above introductory letter can be interpreted as parts of the same line of argumentation, as follows:

(5) SP You should pick (invest in) GE.

(1) (Your goal, as shareholders, is to have a (good) return for your investment.)

(1’) (Investing in GE enables you to reach your financial goal.)

1’.1 GE is different.

1’.1.1 We invest in the future and deliver today.

1’.1.1.1 We develop leadership businesses.

1’.1.1.1.1 In 2007, we demonstrated the ability to create value for our investors through capital redeployment.

(1’.1’) (Uniqueness is a source of competitive advantage.)

The value created for investors in the reporting year becomes an argument for the market leadership of GE’s businesses, and further on, for the ability of the company to “invest in the future and deliver today”. Creating value from capital redeployment signifies delivering results today (short-term value creation) from sound strategic choices of acquisitions and divestitures of businesses, and investing in the future of the company (preparing the portfolio for medium and long-term value creation).

The quality of the strategy that guides the managerial choices leads us to the second main category of argumentative moves used in support of the ability of companies to benefit shareholders: the possession of the “right” means (locus from instrumental cause). As resulting from the corpus of letters, the main argument for the soundness of a strategy is its capacity to enable shareholder value creation. The emphasis can be placed either on the value creation potential of the business strategy as a whole, like in Example no.6 below:

(6) “[…] our greatest opportunity to create value for our shareholders is through further transforming our [business] and by improving its performance further. We believe that we have the right strategy and initiatives in place to achieve this.”

(Letter to our shareholders. Nestlé Management Report 2007: Life, p. 4)

or on the value creation potential of single strategic steps:

(7) “Through an on sale of certain ICI assets to Henkel AG, we expect the acquisition to be value enhancing within three years. This is fully in line with our strategic goal of medium-term value creation.”

(Chairman’s statement. Akzo Nobel Annual Report 2007: Year of Transformation, p. 12)

The value creation potential of the business strategy can also be strategically manoeuvred in order to defend the status quo of the strategy itself. In this final example extracted from the introductory letters of the annual reports, a CEO must face shareholders’ (potential) critiques on the distribution of the profits:

(8) “[Question]: PepsiCo’s businesses generate a lot of cash, and some people may believe the company’s balance sheet is conservative. Will investors see any changes in capital structure, acquisition activity or increased share repurchases?

[Answer]: PepsiCo does generate considerable cash, and we are disciplined about how cash is reinvested in the business. Over the past three years, over $6 billion has been reinvested in the businesses through capital expenditures to fuel growth. All cash not reinvested in the business is returned to our shareholders. […] We will generally use our borrowing capacity in order to fund acquisitions — which was the case in 2007, when we spent $1.3 billion in acquisitions to enhance our future growth and create value for our shareholders. Our current capital structure and debt ratings give us ready access to capital markets and keep our cost of borrowing down.”

(Questions and Answers: A Perspective from Our Chairman and CEO. PepsiCo 2007 Annual Report: Performance with Purpose. The Journey Continues…, p. 9)

The CEO refutes the possible negative connotations of an unchanged financial strategy (suggested in the question by the risk of being perceived as conservative) by highlighting the benefits of that strategy for the shareholders:

(9) SP We will not make changes in the current capital structure, acquisition activity or shares repurchase.

1 Our current strategy is valuable for the shareholders.

1.1a PepsiCo generates a lot of cash.

1.1b We are disciplined about how cash is reinvested in the business.

1.1b.1a All the money reinvested was used to fuel growth (i.e. for future value creation).

1.1b.1b All that remaining cash was returned to shareholders (it created value for the shareholders).

(1.1c) (The current financial strategy allows us to continue to create value for our shareholders in the future.)

1.1c.1a Our current capital structure gives us ready access to capital markets and keeps our cost of borrowing down.

1.1c.1b We use our borrowing capacity in order to fund acquisitions.

1.1c.1b’ Acquisitions enhance our future growth and create value for our shareholders.

(1.1’(a-c)) (If a strategy produces valuable effects, then that strategy is valuable.)

(1’) (If a strategy is valuable for the shareholders, then that strategy should not be changed.)

In order to prove that the current financial strategy is valuable, the CEO tactically chooses to underline not only the value created for the shareholders in the reporting year, but also the expected value that can be created in the future by following this strategy (locus from the instrumental cause, indicated by the premise (1.1’(a-c)). This topical choice is aimed to support the fact that a change of the financial strategy is not necessary, as it would be unreasonable for shareholders to ask for a change in a strategy that has already brought them benefits and it will also enable them to obtain future benefits (the locus from termination and setting up, indicated by the premise (1’)). This could be an effective manoeuvre, unless shareholders have different expectations for the revenues they obtain from their investment (e.g. a preference for immediate short-term gains rather than medium or long-term gains).

As a final observation, I must add that manually checking a random sample of full-text annual reports, I have noticed that the phrase value creation appears only in the narrative sections, and not in the proper financial sections of the reports. That suggests that although (shareholder) value creation is invoked in this category of letters as “the primary measure of business and financial performance” (P&G Annual Report 2007, p.5), the expression does not directly denote an objective financial indicator, its function being mainly rhetorical.

4. Value creation in the introductory letters of the corporate social responsibility reports

The same analytical steps have been followed in the study of the corporate social responsibility reports and the related letters to stakeholders. Like in the case of the annual reports, value creation appeared in 70% of the reports of the corpus, but only in half of their introductory letters.

The pattern of pragmatic meaning outlined by the main recurrent concordances of value and creat* in the corpus of full-text reports shows that value creation maintains its strategic role in this new type of discourse: (“Every company’s aim is to create value. To achieve this aim, decisions are taken and activities developed”). However, the scope of the phrase is extended in terms of presupposed activities, results and beneficiaries: “[we] achieve optimal performance and create sustainable value for all [our] stakeholders” (for employees, customers, communities, governments, society at large) and “for the planet” (the environment). The commitment to sustainability starts at the level of process (“[we] create value by observing the business world from a new perspective”, “through genuine partnership with stakeholders” (customers, communities and governments), and continues up to the level of business effects: “[companies] with distinctive capabilities to create eco-efficient sustainable value will be the winners in the more demanding global market place”, because “developing a relationship with communities does not only create value for them but also contributes to the company’s value“ and “This is both a commercial and CR [Corporate Responsibility] win–win.”.

This pattern is confirmed by the way in which value creation is argumentatively employed in the sub-corpus of letters to stakeholders selected from this type of reports. Being representative of a reporting genre aimed at legitimizing corporations as responsible members of the society, the generic standpoint of the letters to stakeholders is a declaration or a reinforcement of the commitment of the corporations to social responsibility, to the fulfilment of their obligations towards society. Although the precise way in which these obligations are seen may differ from one company to another, the main topics of social responsibility presented in the corpus of letters generally comply with the (deontological) norms of voluntary disclosures on sustainability recommended by the Global Reporting Initiative (2000-2006).

Value creation maintains the supremacy among the corporate goals mentioned in this type of letters, but the range of beneficiaries and constituent activities is significantly extended. An illustrative example is presented below:

(10) “Creating Shared Value: the role of the business in society. […] the fundamental strategy of our Company has been to create value for society, and in doing so create value for our shareholders. […] Creating Shared Value for society and investors means going beyond consumer benefit. […] Creating Shared Value also means bringing value to the farmers who are our suppliers, to our employees, and to other parts of society. It means examining the multiple points where we touch society and making very long-term investments that both benefit the public and benefit our shareholders, who are primarily pension savers or retirees. […] Creating Shared Value additionally means treating the environment in a way that preserves it as the basis of our business for decades, and centuries, to come. […] Creating Shared Value means thinking long term, while at the same time delivering strong annual results. One of the fundamental Nestlé Corporate Business Principles is that ‘we will not sacrifice long-term development for short-term gain’.”

(Creating Shared Value: the role of business in society. The Nestlé Creating Shared Value Report, p. 2)

Basically, the argumentative structure of the Example no.10 can be reconstructed as follows:

(11) (SP) (We are a socially responsible corporation.)

1 We accomplish our role in society.

1.1 We Create Shared Value for society and investors.

(1.1.1a) (Creating Shared Value means bringing benefits to consumers.)

1.1.1b Creating Shared Value means examining the multiple points where we touch society and making very long-term investments that both benefit the public and benefit our shareholders.

1.1.1c Creating Shared Value means bringing value to the farmers who are our suppliers, to our employees, and to other parts of society.

1.1.1d Creating Shared Value means treating the environment in a way that preserves it as the basis of our business for decades, and centuries to come.

1.1.1e Creating Shared Value means thinking long term, while at the same time delivering strong annual results.

1.1.1f [We do all these things.]

(1.1.1f ’) (An entity can be defined with a certain property, if it satisfies (all) the necessary conditions for that property.)

1.1’ The role of the business in society is to Create Shared Value for society and investors.

(1’) (If a company accomplishes its role in society, then that company is socially responsible.)

To prove that it is a socially responsible company, Nestlé shows that it accomplishes the main role of a business in society, i.e. its duty towards society (the locus from efficient cause). In order to do that, Nestlé presents its own vision of the role of the business in society (to Create Shared Value), and strategically defines this new type of value creation by providing a number of necessary conditions related to sustainability that should be satisfied by any socially responsible business. Facts from the reality of the company are then provided in order to prove that all these conditions are satisfied – proofs generically marked in the structure above by the premise 1.1.1f. Thus, in virtue of a complex locus from definition and from the parts and the whole, indicated by premise (1.1.1f ’) – maxim adapted from Rigotti & Greco Morasso 2006-2010[iv] – the company proves that it creates Shared Value; hence, it can be considered socially responsible.

The whole construction of the concept of Shared Value Creation could be considered a persuasive definition (Stevenson 1938; Macagno & Walton 2010) aimed to introduce Nestlé’s vision of the role of the business in society (premise 1.1’) as an already accepted endoxon, without necessarily defending it. The persuasive mechanism of this definition would consist in the transfer of the strong positive connotations acquired by (shareholder) value creation in financial-economic discourse (generally accepted as the aim of a corporation, rigorously implemented and highly appreciated by the target-beneficiaries), to the different, far less regulated domain of sustainability that presupposes different types of activities (some of them still based on voluntarism), and that envisages a wide range of results (not all clearly measurable) and a heterogeneous set of beneficiaries (and expectations). The substitution of the qualifier shareholder with shared in the definition of the new concept of value creation, could also have a peripheral effect of reinforcement of the positive emotions elicited by value creation in this new context. But the true meaning of shared is further (indirectly) indicated in the text by the arguments that prove that the company Creates Shared Value through the activities described in premises 1.1.1a – 1.1.1e. In fact, the social and environmental effects of these activities would eventually benefit the company itself. Two conclusions can be drawn from this aspect. Firstly, the concept of Creating Shared Value, as operationalized in the text, may be a good definition of the role of Nestlé in society, but not of the role of business in general, in which case the premise 1.1’ from Example no. 11 cannot be used as an endoxon. Secondly, even if the premise 1.1’ refers to a general principle that connects social value with corporate performance in terms of moral duty or in terms of business opportunity, the argumentation provided in the text is insufficient in order to consider this premise an endoxon (a generally accepted opinion on the role of business in society) in either way.

As resulting from the sub-corpus of letters to stakeholders, there is however a tendency to use the shareholder value creation potential of sustainability as an argument of socially responsible corporate behaviour, like in Example no.12:

(12) “[Sustainability] is at the center of our strategy and rightfully so. […] [It] contributes to growth and value creation. Initially people thought of it as a cost factor, which indeed it is when you treat it as an add-on. However, if it’s designed into the way you do things from the beginning as it is here at Philips, it saves you money because you’re operating more effectively. So today we recognize that sustainability offers significant business opportunities.”

(Interview with the president. Philips Sustainability Report 2007: Simpler, stronger, greener, p. 8)

In this example, Philips’ president highlights the value-creation opportunities offered by sustainability if it is approached with the “right” managerial attitude (e.g. taking sustainability as the departure point for the production of goods), as opposed to the “wrong” managerial attitude (e.g. superficially implementing it, considering it an add-on):

(13) (SP) (We (will) behave sustainably.)

1 Sustainability contributes to growth and value creation.

1.1a Sustainability offers significant business opportunities.

1.1b Sustainability is not a cost factor.

1.1b.1 Sustainability saves us money.

(1’) (Every company’s aim is to create value.)

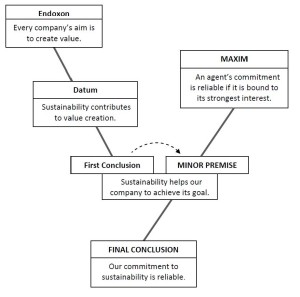

(1’’) (If an action contributes to the achievement of a desired goal, then that action should be undertaken.) [Pragmatic argumentation – locus from final cause]

Or, alternatively:

(1’’’) (An agent’s commitment is reliable if it is bound to its strongest interest.) [Locus from efficient cause] (maxim quoted from Rigotti, Greco Morasso, C. Palmieri & R. Palmieri 2007[v])

I will represent the latter alternative by means of the Argumentum Model of Topics. As in Example no.2, the premise (1’) is an implicit endoxon evoked from the context by the key-phrase value creation:

On the other hand, shareholder value creation, as ultimate corporate aim, can be used as an excuse for not meeting the (excessive) expectations of the stakeholders towards the company, as in the next example:

(14) “Businesses have to be honest about what they are and what they can do. Our goal is to create sustainable shareholder value. Businesses can’t assume the role of governments, charities, political parties, action groups or the many other bodies that make up society.”

(Chief Executive’s Overview. British American Tobacco Sustainability Report 2007, p. 3)

Example no.14 can be interpreted as follows, by means of the locus from final cause – indicated by premise (1.1’) below, and the locus from the parts and the whole – indicated by premise (1’):

(15) (SP) (We cannot resolve (alone) all the sustainability issues of the society.)

1 We cannot assume the role of governments, charities, political parties, action groups or the many other bodies that make up society.

1.1 Our goal is to create sustainable shareholder value.

(1.1’) (A company cannot (be reasonably expected to) assume roles that are not related to its final goal.)

(1’) In order to resolve all the sustainability issues of the society, all social partners must assume their role.

British American Tobacco continues, however, its discourse by constructing a “business case for sustainability” based on the contribution of sustainability to corporate performance, similar to the “win-win” move presented in Example no.13.

5. Conclusions

The purpose of this corpus-based study was to observe the argumentative use of the key-phrase value creation in corporate reporting, by a comparison between the letters to shareholders from the annual reports, and the letters to stakeholders from the corporate social responsibility reports. The analytical tools employed in the study confirmed the status of key-phrase for value creation (as one single unit of meaning), in line with Stubbs’ generic definition of keywords as “words with a special status, either because they express important evaluative social meanings, or because they play a special role in a text or text-type” (in press, p.1). A frequent occurrence in the corpus, value creation was proven to have genre-specific denotative and evaluative meanings, illustrative for the corporate goals, activities and relationships with the stakeholders, thus complying with Williams’ idea of cultural keywords as “[…] significant, binding words in certain activities and their interpretation” (1976, p.13, in Bigi 2006, p.163).

Defining the essence of the agency relationship between corporation and different categories of stakeholders (especially with the shareholders), value creation was frequently used as an argument in both types of letters, usually in close proximity to the principal standpoint of the letter. Complying with Rigotti and Rocci’s model of argumentative keyword, value creation evoked two main goal-related categories of endoxa. The first category stressed the final goal of the shareholders (or stakeholders at large): to obtain what they want (request) from a corporation; the second category stressed the final goal of the corporations: to fulfil their mission towards stakeholders, by providing what they have been asked to provide.

As expected, the ethical debate between the shareholder theory and the stakeholder theory (previously illustrated in Chapter 1) was evident in the argumentation of the two categories of introductory letters. In annual reports, the letters emphasized the ability of a corporation to create value for the shareholders (through unique management qualities or/and the right means) as main argument in order attract investors. Accordingly, the basic argumentative pattern prompted by value creation consisted of a principal move based on the locus from final cause, supported by arguments from efficient cause and from instrumental cause. Although shareholder value creation was considered the ultimate corporate aim in both types of reports, and shareholders were considered the most important stakeholders, a series of attempts to unify the two opposite ethical views (at least at the level of discourse) were observed in the corpus, especially in the letters to stakeholders from the corporate responsibility reports. A first category of attempts was based on the semantic shift of value creation from the financial domain to the domain of social responsibility, Example no.10 being representative in this respect. The second category, most frequently encountered, was based on pragmatic argumentation, viewing sustainability as a potential source of shareholder value creation. Thus, corporations could reasonably be expected to behave sustainably as long as this is in their own best interest – a “win-win” strategy. In my opinion this move, that belongs to the locus from efficient cause, is the most representative for the letters to stakeholders in social corporate responsibility reports.

The intention of this study was not to question the conceptual and ethical approach to value creation of various theories of the firm, but to see how value creation is pragmatically reflected and argumentatively exploited in two sub-genres of persuasive business discourse: the introductory letters to shareholders and stakeholders, from the annual, respectively, corporate social responsibility reports. Although the examples presented in this paper did not exhaust all the argumentative instances of value creation in the corpus letters, I hope that they offered some useful insights on this topic.

NOTES

[i] This study was developed within the framework of the project “Endoxa and keywords in the pragmatics of argumentative discourse. The pragmatic functioning and persuasive exploitation of keywords in corporate reporting”, funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (Grant SNSF PDFMP1_124845/1) and coordinated by Andrea Rocci at Università della Svizzera italiana in Lugano.

[ii] All the reports included in the corpus were published in .pdf format on the websites of the correspondent companies, being identical with the homonymous printed documents.

[iii] EBIT – earnings before interests and taxes.

[iv] The premise (1.1.1f ’) from the argumentative reconstruction of Example no.11 partially reproduces a maxim included in an example of locus from the Argumentum eLearning Module (Rigotti & Greco Morasso 2006-2010).

[v] The premise (1’’’) from the reconstruction of Example no.13 integrally reproduces a maxim included in an example of locus from the e-course Argumentation for Financial Communication, the Argumentum eLearning Module (Rigotti, Greco Morasso, C. Palmieri. & R. Palmieri 2007).

REFERENCES

Becerra, M. (2009). Theory of the Firm for Strategic Management: Economic Value Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bigi, S. (2006). Focus on cultural keywords. Studies in Communication Sciences, 6(1), 157-174.

Clarke, G., & Murray L.W.(B.) (2000). Investor relations: Perceptions of the annual statement. Corporate Communication: An International Journal, 5(3), 144-151.

Eemeren, F.H. van, & Grootendorst, R. (1999). From analysis to presentation: A pragma-dialectical approach to writing argumentative texts. In J. Andriessen & P. Coirier (Eds.), Foundations of Argumentative Text Processing (pp. 59-73). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Global Reporting Initiative (2000-2006). RG. Sustainability Reporting Guidelines, Version 3.0, 1-45. Retrieved August 1, 2010, from http://www.globalreporting.org/NR/rdonlyres/ED9E9B36-AB54-4DE1-BFF2-5F735235CA44/0/G3_GuidelinesENU.pdf

Macagno, F., & Walton, D. (2010). What we hide in words: Emotive words and persuasive definitions. Journal of Pragmatics, 42, 1997-2013.

Rigotti, E. (2006). Relevance of context-bound loci to topical potential in the argumentation stage. Argumentation, 20(4), 519-540.

Rigotti, E. (2008). Locus a causa finali. In G. Gobber, S. Cantarini, S. Cigada, M.C. Gatti & S. Gilardoni (Eds.), L’analisi linguistica e letteraria, XVI (2), Special Issue: Word meaning in argumentative dialogue (pp. 559-576). Milan: Facoltà di Lingue e Letterature straniere, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore.

Rigotti, E., & Greco Morasso, S. (2006-2010). Argumentum eLearning Module. Università della Svizzera italiana, Lugano. Retrieved from http://www.argumentum.ch.

Rigotti, E., Greco Morasso, S., Palmieri, C., & Palmieri, R. (2007). Argumentation for Financial Communication [Electronic course], Argumentum eLearning Module, Università della Svizzera italiana, Lugano. Retrieved March 18, 2007, from http://www.argumentum.ch.

Rigotti, E., & Rocci, A. (2005). From argument analysis to cultural keywords (and back again). In F.H. van Eemeren & P. Houtlosser (Eds.), Argumentation in Practice (pp. 125-142). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Schauten, M. (2010). Shareholder value misunderstood. Valuation Strategies, 13(3), 34-35.

Smith, H. J. (2003). The shareholders vs. stakeholders debate. MIT Sloan Management Review, 44(4), 85-90.

Snoeck Henkemans, A.F. (1997). Analyzing Complex Argumentation: The Reconstruction of Multiple and Coordinatively Compound Argumentation in a Critical Discussion. Amsterdam: Sic Sat.

Stevenson, C.L. (1938). Persuasive definitions. Mind, 47(187), 331-350.

Stubbs, M. (in press). Three concepts of keywords. In M. Bondi & M. Scott (Eds.), Keyness in Texts: Corpus Linguistic Investigations (pp. 21-42). Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Pre-publication version (1-19) retrieved on August 1, 2010, from http://www.uni-trier.de/fileadmin/fb2/ANG/Linguistik/Stubbs/stubbs-2008-keywords.pdf.

Tetreau, É. (2005). Analyste: Au cœur de la folie financière. Paris: Bernard Grasset.

Corpus of corporate reports

a) Annual reports:

Akzo Nobel N.V. (2008). Annual Report 2007: Year of Transformation. Amsterdam: Akzo Nobel Corporate Communications.

Audi AG (2008). Annual Report 2007: Passion; Success Formula for a Mobile Lifestyle. Ingolstadt: Audi AG.

British American Tobacco (2008). Annual Report and Accounts 2007. London: British American Tobacco.

BP plc (2008). BP Annual Report and Accounts 2007. London: BP plc

Canon Inc. (2008). Canon Annual Report 2007. Tokyo: Canon Inc.

Entergy Corporation (2008). 2007 Annual Report: Energy Corporation Presents: “Unlocking Value. Cracking Even the Toughest of Cases!” New Orleans: Entergy Corporation.

General Electric Company (2008). GE Annual Report 2007: Invest and Deliver Every Day. Fairfield: General Electric Company.

GlaxoSmithKline plc (2008). Annual Review 2007: Answering the Questions that Matter. Brentford: GlaxoSmithKline plc.

Heineken N.V. (2008). 2007 Annual Report. Amsterdam: Heineken N.V. Group Corporate Relations.

KBC Group N.V. (2008). Annual Report 2007. Brussels: KBC Group N.V.

Melco International Development Limited (2008). Annual Report 2007: Infinite Vision. Hong Kong/ Macau: Melco International Development Limited.

Nestlé S.A. (2008). Management Report 2007: Life. Cham/ Vevey: Nestlé S.A.

PepsiCo, Inc. (2008). 2007 Annual Report: Performance with Purpose; the Journey Continues… Purchase: PepsiCo, Inc.

Pirelli & C. S.p.A. (2008). Directors’ report and consolidated financial statement at December 31, 2007. Milan: Pirelli & C. S.p.A.

Pirelli & C. Real Estate S.p.A. (2008). Annual Report 2007: Building the Future. Milan: Pirelli & C. Real Estate S.p.A.

The Procter & Gamble Company (P&G) (2007). 2007 Annual Report: Designed to Grow. Cincinnati: The Procter & Gamble Company.

PT Antam Tbk (2008). Annual Report for the Year 2007: Generating Higher Returns for a Better Future. Jakarta: PT Antam Tbk.

Royal Philips Electronics (2008). Philips Annual Report 2007: Simpler, Stronger, Better. Amsterdam: Koninklijke Philips Electronics N.V.

Sinopec Corp. – China Petroleum & Chemical Corporation (2008). 2007 Annual Report and Accounts. Beijing: Sinopec Corp. – China Petroleum & Chemical Corporation.

Škoda Auto a.s. (2008). Skoda Auto 2007 Annual Report: Cars and People. Mladá Boleslav: Škoda Auto a.s.

Vodafone Group plc (2008). Annual Report for the year ended 31March 2008. Newbury: Vodafone Group plc.

Volkswagen AG (2008). Annual Report 2007: Driving Ideas. Wolfsburg: Volkswagen AG.

Volkswagen Bank GmbH (2008). Annual Report 2007. Braunschweig: Volkswagen Bank GmbH.

Volkswagen Financial Services AG (2008). Annual Report 2007. Braunschweig: Volkswagen Financial Services AG.

Volkswagen Leasing GmbH (2008). Annual Report 2007. Braunschweig: Volkswagen Leasing GmbH.

Xerox Corporation (2008). Annual Report 2007: Listening, Connected, Committed to…You. Norwalk: Xerox Corporation.

Xstrata plc (2008). Annual Report 2007. Zug: Xstrata plc.

b) Corporate social responsibility reports:

Akzo Nobel N.V. (2008). Sustainability Report 2007: Year of Transformation. Amsterdam: Akzo Nobel Corporate Communications.

British American Tobacco (2008). Sustainability Report 2007. London: British American Tobacco.

BP plc (2008). Sustainability Report 2007. London: BP plc.

BP Australia Pty Limited (2008). BP in Australia: Sustainability Review 2007-08. Melbourne: BP plc.

BP Azerbaijan SPU (2008). BP in Azerbaijan: Sustainability Report 2007. Baku: BP Azerbaijan SPU.

BP Georgia (2008). BP in Georgia: Sustainability Report 2007. Tbilisi: BP Georgia.

Canon Inc. (2008). Canon Sustainability Report 2008. Tokyo: Canon Inc.

Entergy Corporation (2008). Sustainability Report 2007: Energy Corporation Presents: “Unlocking Value”. Extended Indefinitely! In Environmental, Social and Economic Performance Theatres Everywhere. New Orleans: Entergy Corporation.

General Electric Company (2008). GE Citizenship Report 2007-200: Investing and Delivering in Citizenship. Fairfield: General Electric Company.

General Electric Company (2008). GE ecomagination Report 2007: Investing and Delivering on ecomagination. Fairfield: General Electric Company.

GlaxoSmithKline plc (2008). Corporate Responsibility Report 2007: Answering the Questions that Matter. Brentford: GlaxoSmithKline plc.

Heineken N.V. (2008). 2007 Sustainability Report: Preparing for Our Future. Amsterdam: Heineken N.V. Group Corporate Relations.

KBC Group N.V. (2008). Corporate Social Responsibility Report 2007. Brussels: KBC Group N.V.

Melco International Development Limited (2008). Corporate Social Responsibility Report 2007. Hong Kong/ Macau: Melco International Development Limited.

Nestlé S.A. (2008). The Nestlé “Creating Shared Value” Report 2007. Vevey: Nestlé S.A., Public Affairs.

PepsiCo, Inc. (2008). Overview2007: Our Sustainability Journey. Purchase: PepsiCo, Inc.

Royal Philips Electronics (2008). Sustainability Report 2007: Simpler, Stronger, Greener. Amsterdam: Koninklijke Philips Electronics N.V.

Pirelli & C. S.p.A. (2008). Sustainability Report. In: Pirelli & C. S.p.A., Directors’ report and consolidated financial statement at December 31, 2007 (pp. 177-296). Milan: Pirelli & C. S.p.A.

Pirelli & C. Real Estate S.p.A. (2008). Sustainability Report 2007: Building the Future. Milan: Pirelli & C. Real Estate S.p.A., Communications Department.

The Procter & Gamble Company (P&G) (2007). 2007 Global Sustainability Report: Designed to Grow…Sustainably. Cincinnati: The Procter & Gamble Company.

PT Antam Tbk (2008). Sustainability Report, Year 2007: Operating Sustainably. Jakarta: PT Antam Tbk.

Sinopec Corp. – China Petroleum & Chemical Corporation (2008). Sustainable Development Report 2007. Beijing: Sinopec Corp. – China Petroleum & Chemical Corporation.

Škoda Auto a.s. (2008). Sustainability Report 2007/2008. Mladá Boleslav: Škoda Auto a.s.

Vodafone Australia Limited (2008). Corporate Responsibility Report 2008: Connect; Make the Most of Now. Chatswood: Vodafone Australia Limited.

Vodafone Group Plc. (2008). Corporate Responsibility Report for the year ended 31March 2008: One strategy. Newbury: Vodafone Group Plc.

Vodafone Malta Limited (2008). Corporate Social Responsibility April 2006 – March 2008. Birkirkara: Vodafone Malta Limited.

Vodafone New Zeeland Limited (2008). Corporate Responsibility Report 2008 for the 2008 Financial Year: Open; 10 Years of Vodafone New Zeeland. Auckland: Vodafone New Zeeland Limited.

Vodafone Portugal – Comunicações Pessoais S.A. (2008). Social Responsibility Report 07. Lisboa: Vodafone Portugal – Comunicações Pessoais S.A.

Vodafone Spain (2008). Corporate Responsibility Report 2007-08: Responsible Innovation. Madrid: Vodafone España S.A.

Vodafone UK (2008). CR review. Vodafone UK Corporate Responsibility 2007/08.

Newbury: Vodafone UK.

Volkswagen AG (2007). Sustainability Report 2007/2008: We Are Moving into the Future Responsibly. Wolfsburg: Volkswagen AG, Environment.

Xerox Corporation (2007). 2007 Report on Global Citizenship. Our Word. Our Work. Our World. Norwalk: Xerox Corporation.

Xstrata Alloys (2008). Sustainability Report 2007. Rustenburg: Xstrata South Africa (Pty) Limited Alloys.

Xstrata Copper – El Pachón Project (2008). Sustainability Report 2007. Las Condes: El Pachón Project. Capital San Juan: Xstrata Copper Chile SA.

Xstrata Copper – Frieda River Project (2008). Sustainability Report 2007. Brisbane: Xstrata Queensland Limited. Port Moresby NCD: Frieda River Project Registered Office.

Xstrata Copper – Tampakan Project (2008). Sustainability Report 2007. Tampakan: Tampakan Office. General Santos City: General Santos City Office. Makati City: Sagittarius Mines Inc., Head Office.

Xstrata Copper – Townsville (2008). Sustainability Report 2007. Brisbane: Xstrata Queensland Limited. Townsville: Copper Refineries Pty Ltd.

Xstrata Copper Canada (2008). Sustainability Report 2007.Toronto: Xstrata Copper Canada.

Xstrata Copper North Chile Division (2008). 2007 Sustainability Report. Antofagasta: Xstrata Copper North Chile Division.

Xstrata Copper Southern Peru Division – Las Bambas Mining Project (2008). Sustainability Report 2007. Chacarilla del Estanque: Xstrata Perù S.A.

Xstrata Copper Southern Peru Division – Xstrata Tintaya (2008). Sustainability Report 2007. Vallecito: Xstrata Tintaya S.A.

Xstrata Minera Alumbrera (2008). Sustainability Report 2007. Distrito de Hualfin: Minera Alumbrera.

Xstrata Mount Isa Mines (2008). Sustainability Report 2007. Brisbane: Xstrata Queensland Limited.

Xstrata Nickel (2008). Making Sustainable Progress. Toronto: Xstrata Nickel.

Xstrata plc (2008). Sustainability Report 2007. Zug: Xstrata plc.

Xstrata Zinc North Queensland (2008). Sustainability Report 2007. Brisbane: Xstrata Queensland Limited.

Sub-corpus of introductory messages

a) Documents extracted from the annual reports:

Brabeck-Letmathe, P. (2008). Letter to our shareholders. In: Nestlé S.A., Management Report 2007: Life (pp. 2-5). Cham/ Vevey: Nestlé S.A.

Davis, M.L. (2008). Chief Executive’s report. In: Xstrata plc, Annual Report 2007 (pp. 5-13). Zug: Xstrata plc.

GlaxoSmithKline plc (2008). Company performance (Question three. Share prices in the sector haven’t performed well, what is the outlook for GSK?). In: GlaxoSmithKline plc, Annual Review 2007: Answering the Questions that Matter (pp. 6-7). Brentford: GlaxoSmithKline plc.

Guatri, L. (2008). Chairman’s letter. In: Pirelli & C. S.p.A., Directors’ report and consolidated financial statement at December 31, 2007 (pp. 12-13). Milan: Pirelli & C. S.p.A.

Immelt, J. R.(2008). Letter to investors. In: General Electric Company, GE Annual Report 2007: Invest and Deliver Every Day (pp. 1-9). Fairfield: General Electric Company.

Kleisterlee, G. (2008). Message from the President. In: Royal Philips Electronics, Philips Annual Report 2007: Simpler, Stronger, Better (pp. 10-15). Amsterdam: Koninklijke Philips Electronics N.V.

Lafley, A.G. (2007). Letter to shareholders. In: The Procter & Gamble Company, 2007 Annual Report: Designed to Grow (pp. 2-7). Cincinnati: The Procter & Gamble Company.

Leonard, J.W. (2008). Letter to stakeholders. In: Entergy Corporation, 2007 Annual Report: Energy Corporation Presents “Unlocking Value. Cracking even the toughest of cases!” (pp. 2-6), New Orleans: Entergy Corporation.

PepsiCo, Inc. (2008). Questions and answers: A perspective from our Chairman and CEO. In: PepsiCo, Inc., 2007 Annual Report: Performance with Purpose; the Journey Continues… (pp. 7-9). Purchase: PepsiCo, Inc.

Puri Negri, C.A. (2008). Message from the CEO. In: Pirelli & C. Real Estate S.p.A., Annual Report 2007: Building the Future (pp. 12-13). Milan: Pirelli & C. Real Estate S.p.A.

Volkswagen AG (2008). Talking to. (Prof. Dr. Martin Winterkorn is interviewed by Dirk Maxeiner). In: Volkswagen AG, Annual Report 2007: Driving Ideas (pp. 14-17). Wolfsburg: Volkswagen AG.

Wijers, H. (2008). Chairman’s statement. In: Akzo Nobel N.V, Annual Report 2007: Year of Transformation (pp. 12-14). Amsterdam: Akzo Nobel Corporate Communications.

b) Documents extracted from the corporate social responsibility reports:

Adams, P. (2008). Chief Executive’s overview. In: British American Tobacco, Sustainability Report 2007 (pp. 2-3). London: British American Tobacco.

Brabeck-Letmathe, P. (2008). Creating Shared Value: the role of business in society. In: Nestlé S.A., The Nestlé “Creating Shared Value” Report 2007 (pp. 2-3). Vevey: Nestlé S.A., Public Affairs.

Davis, M.L. (2008). Chief Executive’s report. In: Xstrata plc, Sustainability Report 2007 (pp. 2-3). Zug: Xstrata plc.

Mulcahy, A.M. (2007). Chairman’s letter. In: Xerox Corporation, 2007 Report on Global Citizenship. Our Word. Our Work. Our World (pp. 1-3). Norwalk: Xerox Corporation.

Nienaber, P.J (2008). CEO’s review. In: Xstrata Alloys, Sustainability Report 2007 (p. 1). Rustenburg: Xstrata South Africa (Pty) Limited Alloys.

PepsiCo, Inc. (2008). Sustainability Q&A with Indra Nooyi, PepsiCo Chairman and CEO. In: PepsiCo, Inc., Overview2007: Our Sustainability Journey (pp. 2-3). Purchase: PepsiCo, Inc.

Royal Philips Electronics (2008). Interview with the president. In: Royal Philips Electronics, Sustainability Report 2007: Simpler, Stronger, Greener (pp. 8 -11). Amsterdam: Koninklijke Philips Electronics N.V.

Royal Philips Electronics (2008). Becoming simpler, stronger and greener. In: Royal Philips Electronics, Sustainability Report 2007: Simpler, Stronger, Greener (pp. 12-13). Amsterdam: Koninklijke Philips Electronics N.V.

Sarin, A. (2008). Message from the Chief Executive. In: Vodafone Group Plc, Corporate Responsibility Report for the year ended 31March 2008: One Strategy (pp. 9-10). Newbury: Vodafone Group Plc.

Su, S. (2008). Welcome from the Chairman. In: Sinopec Corp. – China Petroleum & Chemical Corporation, Sustainable Development Report 2007 (pp. 3-4). Beijing: Sinopec Corp. – China Petroleum & Chemical Corporation.

Wijers, H. (2008). Chairman’s statement. In: Akzo Nobel N.V., Sustainability Report 2007: Year of Transformation (pp. 8-9). Amsterdam: Akzo Nobel Corporate Communications.