ISSA Proceedings 2010 – Contemporary Trends: Between Public Art And Guerrilla Advertising

One of the most discussed areas in Contemporary Art is Public Art. It has existed as a distinctive trend since the early Seventies. Born as a form of guerrilla art that tried to invade non-institutional spaces through performing actions, the term refers today to works of art in any media that have been planned and executed with the specific intention of being sited or staged in the public domain, usually outside and accessible to all. Advertising shows something similar in so-called guerrilla advertising, which avoids the institutional displays in favour of unexpected happenings and perturbant installations, which are not immediately recognizable as commercials. The aim of this paper is to articulate and compare the two terms in order to define them in a dialectical, non-dogmatic way, underlining their argumentative development. This shows on one hand the passage from the work of art as an aesthetical object to contemplate inside a museum to a dialectical event developed as performances, installations and happenings that transform the public space, creating a gap into normal life, that gives space to a new unexpected point of view on our everyday reality. On the other hand advertising using similar strategies starts using new unexpected spaces like zebra crossing, public toilets, underground floor, just to recall some examples. not only to persuade the consumers, but also to entertain them through a more and more interactive setting. Moreover, we’ll try to answer following question: Does guerrilla advertising put into question contemporary art’s creative power?

One of the most discussed areas in Contemporary Art is Public Art. It has existed as a distinctive trend since the early Seventies. Born as a form of guerrilla art that tried to invade non-institutional spaces through performing actions, the term refers today to works of art in any media that have been planned and executed with the specific intention of being sited or staged in the public domain, usually outside and accessible to all. Advertising shows something similar in so-called guerrilla advertising, which avoids the institutional displays in favour of unexpected happenings and perturbant installations, which are not immediately recognizable as commercials. The aim of this paper is to articulate and compare the two terms in order to define them in a dialectical, non-dogmatic way, underlining their argumentative development. This shows on one hand the passage from the work of art as an aesthetical object to contemplate inside a museum to a dialectical event developed as performances, installations and happenings that transform the public space, creating a gap into normal life, that gives space to a new unexpected point of view on our everyday reality. On the other hand advertising using similar strategies starts using new unexpected spaces like zebra crossing, public toilets, underground floor, just to recall some examples. not only to persuade the consumers, but also to entertain them through a more and more interactive setting. Moreover, we’ll try to answer following question: Does guerrilla advertising put into question contemporary art’s creative power?

1. An articulated definition of Public Art

The name Public Art itself seems to be more a general feature of any art form, rather than a relatively new trend; any artistic expression needs, in fact, to be public in order to exist, so even a museum is a public space, not only the so-called non-institutional spaces. Nevertheless, Vito Acconci stated that a Museum is a “simulated” public space where people go in order to find art, so this could be defined a museum’s audience and therefore a specific audience. “A museum is a “public space” but only for those who choose to be a museum public. A museum is a “simulated” public space; it’s auto-directional and uni-functional. When you go to a railroad station, you go to catch a train, but in the meantime you might browse through a shop. When you go to the museum, you have to be a museum-goer”[i] (Matzner et. al., 2001, p.45). So we define Public Art as the art forms performed or realized in the public domain meeting a generic public audience. But does this audience share some common information? In other words, does a generic public exist? Gerard A. Hauser pointed out that, according to Dewey, “the public is in eclipse” (Hauser 2005, p.268). Last but not least we could also add a quotation of the geographer Yi-Fu Tuan, who pointed out in 1976 that: “When the space seems familiar to us, it means that it has become a place” (Dean-Millar 2006, p. 14). This could become another interesting criteria by which to examine good and bad examples of Public Art and we could attempt to add another definition: “Public Art transforms landscapes and spaces into familiar art-places.” If we accept these assumptions, we could also affirm that an effective artistic intervention creates dialectical objects that revitalise the surroundings and those who live and stop there while creating or recreating a sense of belonging and reflection. The place is something known to us, something that belongs to us in a spiritual and non-material way and to which we belong. After this last reflection on the concepts of space and place, it is important to see in which ways they are transformed by public art works. Following my research journey and that of some artists close to me I have tried to articulate public art works typologies according to the following groupings:

– Permanent site-specific interventions: long lasting installations which always imply an official project.

– Temporary site-specific interventions: which could be official or unauthorised installations.

– Audience-specific interventions: performances and happenings planned according to the inhabitants of a specific area.

– People-specific interventions: projects shared with one or more people with whom we have already a relationship.

1.1. The origin of Public Art as a politically and socially engaged art form

Before analysing these actual typologies it is important to dedicate some words to the development of Public Art from its first appearance. As we said previously, even if its origins were quite different, we often tend to identify Public Art with the so-called permanent site-specific works, carried out in collaboration with the institutions, which generally tend to lose their dialectical power after a while, as monuments do. The economist Pierluigi Sacco points out that “If a general interlocutor is asked what Public Art is, the answer will probably be: an equestrian statue or another type of monument. For a long time, Public Art was primarily this: an exercise in commemorative rhetoric to which – in the best case scenario – citizens get used to and in the worst they regard it as a permanent affront” (Sacco 2007, p. 11). Nevertheless, the concept developed in a more complex way starting with extemporary art actions at the end of the Seventies. The first public art works were performances and happenings which created statements against the official art world or politically engaged ones. Public Art developed art actions that we could call visual and verbal argumentative speech acts that can be interpreted following the three principles of visual communication pointed out by Leo Groarke: -The first is the principle that images that are designed for argument, are communicative acts that are in principle understandable. Among other things, this principle implies that images that are, taken literally, absurd or contradictory should be interpreted in a non-literal way, for it is only in this way that they can make a comprehensible contribution to discussion. -A second principle of visual communication is the principle that argumentative images should be interpreted in a way that makes sense of the major (visual and verbal) element they contain. This implies an interpretation that interprets each of these components plausibly, and plausibly explains their connection to each other. -The third principle of visual communication is the principle that we must interpret argumentative images in a way that makes sense from an “external” point of view-in the sense that it fits the social, critical, political and aesthetic discourse in which the image is located. (Groarke in Van Eemeren, 2002, p. 145).

Then, in order to determine the most evident key of interpretation, in order to fulfil the previous second principle: making sense of the major, it can be useful to use Sorin Stati’s scheme, divided into pragmatic functions and argumentative roles. The pragmatic function and the argumentative roles are similar semantic factors because they concern the goal of the speaker, but only the argumentative roles reveal his real purposes. The pragmatic functions and the argumentative roles could also be explained as the text meaning and the speaker’s meaning, pointing out the discrepancy which often characterises the discourse. The expected or the unexpected relationships between pragmatic functions and argumentative roles are often the result of a strategy to differentiate or to emphasise various types of communication; they often create a surprise effect that is welcomed in art works.[ii]

1.1.1. Group Material: participation through interpretation

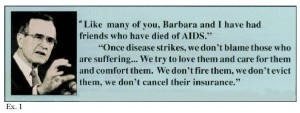

Group Material, a New York-based collaborative group founded in 1979 was one of the first examples of Public Art. They questioned issues related to democracy, discrimination and the art establishment, creating audience-specific projects, created in order to exercise a critique or to recall forgotten events or situations. “Our working method might best be described as painfully democratic, because so much of our process depends on the review, selection, and critical juxtaposition of innumerable cultural objects, adhering to a collective process is extremely time-consuming and difficult. However, the shared learning and ideas produce results that are often inaccessible to those who work alone. Our exhibitions and projects are intended to be forums in which multiple points of view are represented in a variety of styles and methods. We believe, as the feminist writer Bell Hooks has said, that “we must focus on a policy of inclusion so as not to mirror oppressive structures. As a result, each exhibition is a veritable model of democracy. Mirroring the various forms of representation that structure our understanding of culture, our exhibitions bring together so-called fine art with products from supermarkets, mass-cultural artifacts with historical objects, factual documentation with homemade projects. We are not interested in making definitive evaluations or declarative statements, but in creating situations that offer our chosen subject as a complex and open-ended issue. We encourage greater audience participation through interpretation.”[iii] They were not interested in making definitive evaluations or declarative statements, but in creating situations that offer a complex and open-ended issue. They encouraged greater audience participation through interpretation. The “AIDS Timeline”, a mixed-media installation, (wall paper in a gallery, a poster on a bus and pamphlets distributed in several places) reconstructs, for instance, the history of AIDS as embedded within a web of cultural and political relations.“They tried to recreate a chronology of the syndrome. The timeline suggests that AIDS has been constructed through both a bio-medical discourse of infection, incubation, and transmission as well as a cultural vocabulary of innocence and guilt, dominance and deviance” [iv].The bus poster showed an image of President Bush with a quote referring to insurance coverage of people with AIDS and conveyed positive norms of behaviour: “Like many of you Barbara and I have had friend who have died of AIDS. Once disease strikes, we don’t blame those who are suffering…we try to love them, to care for them and confort them. We don’t fire them, we don’t evict them, we don’t cancel their insurance” (Ex.1).

In the meantime, a pamphlet about the insurance industry and AIDS written by Mary Anne Staniszewski was distributed to tie in with the poster publicity in order to transform its message into an argumentative role of critic against hypocrisy.

1.1.2. Guerrilla Girls and the Girl Power

Among the best examples of Public Art, we also remember the collective feminist group of the “Guerrilla Girls” founded in 1985. They assumed the names of dead women artists and wore gorilla masks in public, concealing their identities and focusing on the issues rather than on their personalities.. They define themselves as it follows: “We’re feminist masked avengers in the tradition of anonymous do-gooders like Robin Hood, Wonder Woman and Batman. How do we expose sexism, racism and corruption in politics, art, film and pop culture? With facts, humour and outrageous visuals. We reveal the understory, the subtext, the overlooked, the unfair. We’ve appeared at over 90 universities and museums, as well as in The New York Times, The Washington Post, The New Yorker, Bitch, and Artforum; on NPR, the BBC and CBC; and in many art and feminist texts. We are authors of stickers, billboards, many, many posters and other projects, and several books including The Guerrilla Girls’ Bedside Companion to the History of Western Art and Bitches, Bimbos and Ballbreakers: The Guerrilla Girls’ Guide to Female Stereotypes. We’re part of Amnesty International’s Stop Violence Against Women Campaign in the UK; we’re brainstorming with Greenpeace. In the last few years, we’ve unveiled anti-film industry billboards in Hollywood just in time for the Oscars, and created large scale projects for the Venice Biennale, Istanbul and Mexico City. We discussed the Museum of Modern Art at its own Feminist Futures Symposium, examined the museums of Washington DC in a full page in the Washington Post, and exhibited large-scale posters and banners in Athens, Bilbao, Montreal, Rotterdam, Sarajevo and Shanghai. What’s next? More creative complaining! More facts, humour and fake fur! More appearances, actions and artworks. We could be anyone; we are everywhere“.[v]

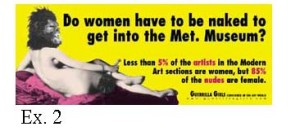

They create billboards containing visual and texts, often using the pragmatic function of the rhetorical question, in order to express the argumentative role of critique and recall about the fact that sexism and racism are pervasive throughout the world of art and popular culture. Women artists and artists of colour are greatly underrepresented in art museums. Women and people of colour are also under acknowledged and underappreciated in the film industry. Let’s analyse two of these posters.

The visual of the first (Ex. 2) is based on Ingres’ famous Odalisque apart from the head, that has been disguised with the typical gorilla mask. The headline goes: “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum?”. From this rhetorical question we can infer an argumentative critical conclusion well explained through the words of the artists themselves, who comments on the development of the situation after their work:

“On September 1, 2004, we did a recount. We were sure things had improved. Surprise! Only 3% of the artists in the Modern and Contemporary sections were women (5% in 1989), and 83% of the nudes were female (85% in 1989).” [vi]

In another billboard, they create an ironical list of the false advantages of being a woman artist, to state their lack of opportunities:

“Working without the pressure of success

Not having to be in shows with men

Having an escape from the art world in your 4 free-lance jobs

Knowing your career might pick up after you’re eighty

Being reassured that whatever kind of art you make it will be labeled feminine

Not being stuck in a tenure teaching position

Seeing your ideas live on in the work of others

Having the opportunity to choose between career and motherhood

Not having to chose on those big cigars or paint in Italian suits

Having more time to work when your mate dumps you for someone younger

Being included in revised versions of Art History

Not having to undergo the embarassement of being called a genius

Getting your picture in the art magazines wearing a guerrilla suit”

Here the Girls attack not only the difficulties of being recognized as a female artist, but also the difficulties of balancing a professional life with a personal one in a society which undervalues women’s contributions. Later, this artistic trend of moving out from the institutions became a simply formal trend of showing something outside the museum or the gallery and it was embraced by the official institutions as a land of possibility for big and long lasting “urban furniture”.

So even if its origins were quite politically and socially engaged, this is why we often tend to identify Public Art with these so-called permanent site specific works, carried out in collaboration with the institutions; in the following paragraph, we will analyse some examples.

1.2. Permanent Site-Specific art works: Jeff Koons

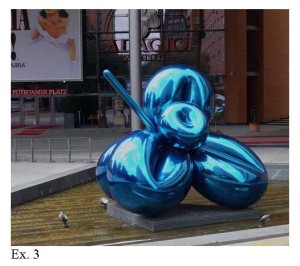

Permanent site-specific projects refer to those interventions that place more or less articulated sculptures or installations in open spaces permanently. Broader processes correspond with these operations: Let’s take for example “Balloon Flower” by Jeff Koons, displayed as a permanent installation in Potsdamer Platz in Berlin (Ex. 3).

He has realized a blue flower by the “bending” of a steel air-ballon. Balloon Flower is the perfect example of the ability of the American artist to transform a common image into popular mythology. Balloon Flower is a monument to nostalgia and reflects the way in which children see the world. Balloon Flower provides the viewer with a sensuous image with strange tensions between lightness and weight, between the ephemeral and the eternal.

“For Koons, there are great links, and indeed parallels, between man and flower. While flowers have their annual cycle, so too do humans, but our year is made of strange markers, many of them associated with life and with sex: Valentine’s Day, anniversaries, Spring… And all these events can involve flowers.[vii] So it also acts as a symbol of time and of human relationships, the perfect metaphor to be set in a public square. Nevertheless, we are far from the political engagement of the works we have previously analysed.

Moreover, despite the good intentions, the outcomes of this type of projects are often questionable because using public space can also involve the risk of creating a celebrative product, limited therefore to delimiting a landscape or changing a horizon, rather than a dialectical object. Vito Acconci is very critical in this regard: “What’s called public space in a city is produced by a government agency (…). What’s produced is a product. (…) What’s produced is a “production”: a spectacle that glorifies the corporation or the state.”[viii] In the last two decades, we have a countertrend which tries to recall the first ideals of this art form, moving from the permanent site specific to the temporary site specific, to the audience specific and finally to the people specific projects, according much more importance to the human community of a given space, than to the space itself.

1.3.Temporary Site Specific art works: Christo and Jean Claude

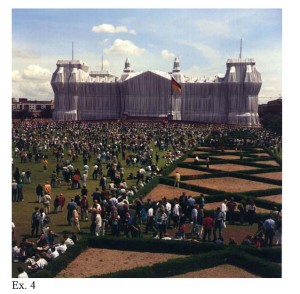

“The process allows artists to work on the public environment and integrate their vision of space and of the social processes that take place in it. The artist is called upon to work not for himself but for the people who interact in that specific context” (Scotini in Sacco 2006, p.100). Temporary site-specific installations involve artistic actions or installations of brief duration that create events more or less incisive on the context. Being ephemeral, they maintain their dialectical power as they do not become part of the common landscape, in front of which the citizen tends to be more and more indifferent. Emblematic in this regard is Christo’s “Wrapping of the Reichstag”, realized in 1995 (Ex. 4).

The artist wrapped the past and future building of the German government in silver polypropylene, covering a building that was becoming ever more an anonymous element of the landscape and ever less a place of belonging and memory.This happening created an oxymoron that could be expressed as follows: “Cover to rediscover!” with many possible argumentative implications, implying, for instance, the necessity of taking into account all historical, political and even aesthetical connotations connected with this building in order to revisit the German identity. The Reichstag was constructed to house the “Reichstag”, which was the name of the German Parliament, till 1933 when the building caught fire under circumstances still not clear. This gave to the Nazis the excuse to suspend most of the rights provided by the constitution, in the so called “Reichstag Fire Decree”. The building started being used for propaganda’s purposes, becoming a negative symbol and one of the main target of the Red Army bombing. Later it remained on the Western border near the Berlin wall representing the failure of democracy. After the reunion the possibility of pulling down the Reichstag was taken into serious account because of its difficult restoration, but probably also for its political and historical antithetical implications. At the end the choice of it as the future Government Building was the result of the want to return the capital from Bonn to Berlin and also the need to rescue a place from oblivion underlining its regained role. This choice was also a possible implicit question: “If you don’t talk and look at the past, would it become easier to accept?” Using the argumentative role of thesis to stress the importance of talking about the past in order to overcome it. At the time when Christo proposed his project the emotive and historical argumentative power returned forcefully to the fore and suddenly this “forgotten place” became a familiar place again, too familiar, warm and insidious, for the contrasting historical events it recalled, one need only consider that the artist had to wait 25 years for the necessary authorisation. This wait became an integral part of this beautiful work which apparently lasted only 15 days but contributed to giving back a landmark to the Berliners, which would last for many years.

1.4. Audience Specific: Annalisa Cattani, Amanda McGregor, Adriana Torregrossa, Dragoni-Russo

With audience-specific, the art critic and curator Marco Scotini refers to projects aiming at a more profound and capillary involvement of the social structure. There are many Italian examples, often starting with an infringement of regulations, evading permission and invading unexpected spaces, the casual public finding itself in the vicinity is the first recipient and often becomes a voluntary or involuntary protagonist of the work.

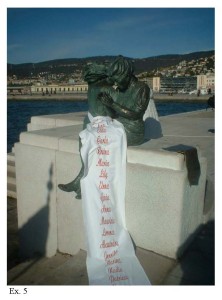

The following project by Annalisa Cattani: The girls of Trieste (Ex. 5) followed this line.

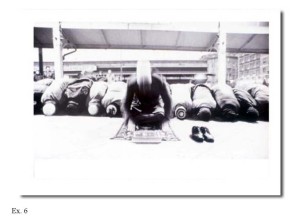

In this case, involvement happens by acting on memory. A pre-existing monument became the drive of the work. Too often monuments lose their function of manere and monere (staying and reminding) as the etymology of the term would mean, becoming backgrounds only for photos or points of reference for finding one’s bearings. In this case “The girls of Trieste”, a monument to the women who sustained their men during the war by symbolically sewing the flag became, with the addition of an embroidered cloth with tens of names taken from the archives of the psychiatric hospital, the voice of the forgotten women deceased in mental hospitals, in memory of what happened and as a warning of that which should never happen again. Following Hauser’s point of view “when artistic portrayal is co-extensive with actual and I would add with historical events, these deliberations may organize public memory in other than official terms, thereby shaping society’s understanding of its own historicity and the model of its own self-organization” (Hauser 2005, p. 270). The London artist Amanda McGregor proposed an Alternative City Planning for the town of Letchworth, involving people, occupying various roles in the social structure, in a psychodynamic journey, towards the place they live in, guided by an exercise of “creative visualisation”, that produced unexpected looks, hidden desires, ways for alternative solutions. In this case, the citizens involved became effective interlocutors who could really take part in determining the urban planning of their town, not simply by voting the members of the administration. It created that which Matzner pointed out as follows: It is not about the gap between culture and public, but it is to make art public and artists citizens again (Matzner 2001, p.107). Over the years, this type of operation in Public Art has acquired ever greater complexity and prominence. The artist, therefore, often becomes the voice of marginal cultures, the artists Siah Armajani and Mischa Kuball express themselves as such in this regard: Public Art comes in through the back door, like a second class citizen (…)Public Art can present itself as the voice of marginal culture, as the minority report, as the opposition party (Matzner 2001, p. 45). In this regard, it is necessary to mention a very interesting and effective work by Adriana Torregrossa: “Article 2”. The operation outlined by the artist takes the title from the second article of the Italian Constitution which grants citizens the possibility of expressing their own culture. Torregrossa made it possible to sing the prayer of the end of the Ramadan in the marketplace in Turin in order to produce a critical answer to article 2 as, in Torregrossa’s point of view it was not respected in this town where there are not enough places dedicated to minorities to grant their rights (Ex. 6).

Piazza del Mercato di Porta Palazzo in Turin is an area inhabited for the most part by immigrants of the Islamic religion; this is why she wanted to transform the market just for a few minutes into a Middle-Eastern square, in order to give immigrants the presence of a familiar and shared place for a brief time. Two Bolognese artists, Dragoni and Russo, created an interesting audience-specific project, Noting the presence of makeshift seats at the bus stops in the suburbs, the artists intervene adding a name plate stating: Gift of the Dragoni-Russo family, mimicking those which can be found on church pews. This subtle criticism of the negligence of the city’s administration shows, at the same time, a provincial stance on socialisation, a tendency toward making domestic a public space, which thus becomes a place. A further implication associated with this definition of Public Art is given by the artists Siah Armajani and Mischa Kuball: “Public Art must go beyond the personal gesture of the artist, must transcend pure subjectivity and respond to the urban, social and political structure that define a given place” (Matzner, 2001, p.461).

1.5. People Specific: Darth

As regards people-specific projects, reference is made to works implying ever closer relational processes and at times involving actual neighbours. A small number of people are involved. In relation to this, we recall the work “Venti-trenta-quaranta metri” by Annalisa Cattani. This sound installation, showing a speaking hole in a castle, makes the artistic action an engine that brings into play sense and memory processes among neighbours while transforming the form into a dialectical object. As for many other fortresses and castles, it is narrated that the Rocca di Stellata fortress had an underground passageway of uncertain depth – between twenty and thirty metres – which would have connected it with the villa of the owners. However, for years, there has only been weak proof of this story, consisting in an accidental excavation and the recounting of the children of yesteryear who made the entrance of that cave the setting for their adventures. The image of this space, by now lost and covered with sand by the floods of the Po river, has been excavated in memory of Sergio Calori, Ermete Migliari and the watchman Ramon, and serves as a release for a flurry of rumours and stories from those who lived inside the fortress, from those who observed it in the immediate vicinity and finally of those who still diffuse its memory today. In each of the declarations, the underground passageway is present together with the sense of limit, of the prohibited, towards a threshold that was not to be crossed and became a mental matrix of the protagonists of an age. Another example is given by the “Encounters behind closed doors” with Darth, a group of artists and curators, that became, to all intents and purposes, a meta-artistic work and was created from the necessity to problematize the distance between generic and specific audiences, but among specialists in the most mindful way. During this meeting, artists, curators and gallerists were invited without an audience, just for the founder of the association, in order to reestablish a shared language among specialists. Sometimes, in Italy contemporary art concentrates too much on a sort of universal audience losing the specificity of the discipline and also its argumentative force. The result of these encounters was videotaped and shown just as a trailer in some galleries in order to let people taste the atmosphere, but also to point out the impossibility of reproducing the event which was an emotional and argumentative mix that had to be lived and not re-enacted.

Let’s now see how this development in Public Art affected advertising.

2. Guerrilla advertising between viral marketing and audience-specific

Public Art influenced Guerrilla Advertising most of all: a relatively new trend in advertising whose aims and forms can be compared with those of Public Art. “Guerrilla advertising” is a catch-all phrase for non traditional advertising campaigns that take the form of theatrically staged public scenes or events, often carried out without city permits or advance public hype. It was first coined by author Jay Conrad Levinson in 1984 to refer to unconventional, non-big-media-dependent brand-building exercises (…) These were once a low-budget strategies for start ups and small businesses unable to afford a thirty-second spot.”[ix] Even with this point of view, its origins are very similar to those of Public Art which emerged as an answer against the big and rich art world, to create new spaces for creativity. Let’s start with some audience-specific examples. As we showed previously, these kind of performances and happenings create a gap in every day life; they appear all of a sudden and are oriented to the audience and not to a given or chosen space. They imply an interaction with the public and correspond to what is normally called viral marketing. Like its name implies, it is a way of spreading your message like a virus from person to person. Microsoft covered Manhattan in butterfly stickers for example. This approach is particularly effective in social advertising. Let’s take an example made to let people quit smoking, creating peculiar trashcans on the streets that warn smokers of dangers. (Ex. 7).

Public Art influenced Guerrilla Advertising most of all: a relatively new trend in advertising whose aims and forms can be compared with those of Public Art. “Guerrilla advertising” is a catch-all phrase for non traditional advertising campaigns that take the form of theatrically staged public scenes or events, often carried out without city permits or advance public hype. It was first coined by author Jay Conrad Levinson in 1984 to refer to unconventional, non-big-media-dependent brand-building exercises (…) These were once a low-budget strategies for start ups and small businesses unable to afford a thirty-second spot.”[ix] Even with this point of view, its origins are very similar to those of Public Art which emerged as an answer against the big and rich art world, to create new spaces for creativity. Let’s start with some audience-specific examples. As we showed previously, these kind of performances and happenings create a gap in every day life; they appear all of a sudden and are oriented to the audience and not to a given or chosen space. They imply an interaction with the public and correspond to what is normally called viral marketing. Like its name implies, it is a way of spreading your message like a virus from person to person. Microsoft covered Manhattan in butterfly stickers for example. This approach is particularly effective in social advertising. Let’s take an example made to let people quit smoking, creating peculiar trashcans on the streets that warn smokers of dangers. (Ex. 7).

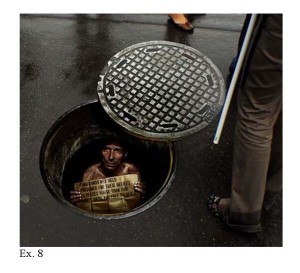

To make people aware of Prisoner’s rights, Amnesty did a stickering campaign in order to reach people from the audience one by one. The sticker simulated an hole in the street showing a prisoner inside with a message in his hands saying: “Thousands are held prisoners for their beliefs in places worse than this. Write until you free them all. Amnesty International”. To raise awareness for the Weingart Homeless Center (Ex. 8), they took a non traditional approach that made people imagine themselves homeless if only for a moment, provoking a self critique for the indifference they were victim of. They photographed a dozen of the 70.000 people living on the streets of Los Angeles.

They then took those images, removed their faces and made them into photo-realistic cardboard cut-outs. They placed the cutouts in upscale shopping centres in Beverly Hills and Santa Monica. Soon the homeless could not be ignored. This project not only raised awareness, but it also raised funds. Amnesty International in Germany celebrated the 60th anniversary of human rights in 2008 with “Frau im Koffer”, “Woman in suitcase”, an ambient advertising campaign at German airports. “Woman in Suitcase” (ex. 9). It consisted in putting a woman in a transparent suitcase and sending her around the baggage carousel of the airport, again using the visualization instead of the verbal thesis to shock and to criticise our indifference towards this problem.

They then took those images, removed their faces and made them into photo-realistic cardboard cut-outs. They placed the cutouts in upscale shopping centres in Beverly Hills and Santa Monica. Soon the homeless could not be ignored. This project not only raised awareness, but it also raised funds. Amnesty International in Germany celebrated the 60th anniversary of human rights in 2008 with “Frau im Koffer”, “Woman in suitcase”, an ambient advertising campaign at German airports. “Woman in Suitcase” (ex. 9). It consisted in putting a woman in a transparent suitcase and sending her around the baggage carousel of the airport, again using the visualization instead of the verbal thesis to shock and to criticise our indifference towards this problem.

Now even big-name brands are taking the guerrilla approach. It offers a way to engage highly targeted audiences, to develop a streetwise identity or simply to reach consumers who are so inundated with advertisements that they tend to ignore them. The advertising industry is in a state of flux, in an age where we can choose what media we utilise, the traditional channels of TV, press and poster are no longer always the most appropriate for a brand to reach its target audience. As a result, global brands are opting to implement ever more inventive and original schemes to get their products talked about. All of a sudden poor and low budget guerrilla methods like stickering, graffiti, etc have become new and creative earning opportunities. On the other hand, this trend has disempowered the political feedback of these operations, promoting big scale temporary site-specific installations much more decorative than argumentative near the viral trend.

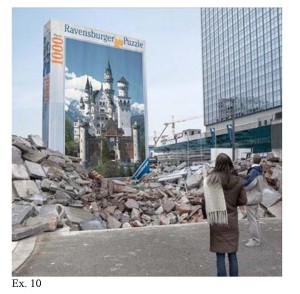

2.1.Temporary Site-Specific or Ambient Campaigns

These are very high budget campaigns which create a big urban installation to promote the products in an unexpected way. Ravensburger, the manufacturers of many popular puzzles and games, recently launched a billboard campaign in Berlin, Germany to promote sales of their 1001 piece puzzles. The boards are shaped like puzzle boxes and contain images of internationally recognized landmarks, such as The White House. The “boxes” are surrounded by real, three-dimensional rubble, giving the impression of a “life sized” puzzle. Nevertheless, this visual hyperbole remains a figure of style that simply creates a sense of wonder and a “fairy tale effect” (Ex. 10).

2.2. People Specific Advertising

Guerrilla marketing can also work as a form of neighbourhood marketing, as happened in a door to door stickering. A sticker featuring the model Eva Padberg holding Otto’s catalogue with the order number, was attached to the spyholeof thousands of houses around Germany. In a similar campaign, the customers are reached one by one and they feel important and special; the dimension is very domestic.

3. Conclusions

In the overall context of possible definitions of Public Art and Guerrilla Advertising lies the relationship between self, environment and others which no longer converges today in a single topos but flows in a dialectical dynamic in which art creates stages of visual reflection. When advertising does something similar, surely the main goal remains to get you to do something. Whether that something is buying a product, seeing a movie or, as in the picture above, stop smoking, marketers play on psychological principles to affect our behaviour and tend to close the discourse. On the contrary Public Art started and continues to gain new democratic spaces for creativity. All operations placed outside institutional spaces also bring into discussion the inside and, therefore, the system of art and culture in general while turning to the world as a source of experience and knowledge. Furthermore, the projects of brief duration more than others put the status of the work of art as an eternal and stable expression into decline while promoting the short-lived aspect as an argumentative content and not only as pure form. On the other hand guerrilla advertising and advertising in general shows the capacity of creating or of embodying the avantgarde trends, opening many implication that go much further the promotion of a product or in the case of social advertising of an attitude, they diffuse a life style and a life philosophy even normalizing controversial situations.

NOTES

[i] “The consequences on human association of rapidly changing condition of economy, work, travel and information transfer on human association, he notes that desires and purposes created by the machine age are disconnected from the ideal of tradition. (…) Our Babel is not one of tongues but of the signs and symbols without which shared experiences is impossible” (…) The remedy for this breakdown is art. More important than the content of an artwork is the artist’s power to bond strangers in shared experience through portraits constructed with signs and symbols that evoke deeper reflection. (…) The freeing of the artist in literary presentation, in other words, is a much a precondition of the desirable creation of adequate opinion on public matters as is the freeing of social inquiry. Men’s conscious life of opinion and judgment often proceeds on a superficial and trivial plane. But their lives reach a deeper level. The function of art has always been to break through the crust of conventionalized and routine consciousness(to touch the deeper levels of life so that they spring up as desire and thought” (…) “They are creation of imagination intended to be performed their performance brings members of society together as an audience. Their performance presents the artist’s claim about human feelings, relations and actions. Moreover their audiences are not just spectators whose function is to witness, they are also engaged. They don’t simply have to contemplate, they invite deliberation (Hauser 2005, p. 268-269).

[ii] L’étude de ces deux couches du signifié des phrases pourrait servir comme définition de la pragmalinguistique.” (Sorin Stati, Le Transphrastique, Puf, Paris, 1990, p.16).

Here is a simplified version of the scheme:

Pragmatic Functions

performing function (the speaker performs an act of doing rather than saying)

recall function (the speaker reminds to his interlocutor facts he has to know, or invites him to note an evidence)

erotetic function (pertaining to question, pertaining to a rhetorical question)

assertive function (frasal context, that gives a new information)

epistemic function (expression of the locutor in order to proof that he knows something)

directive function (orders, invitations, advices. We distinguish two classes:

1: directive whose goal is to provoke a verbal action.

2: directive whose goal is to provoke a non verbal action

expressive emotional function

commissive function: (its two main variants are: menace and promise)

Argumentative Roles

Positive: approval, thesis, conclusion, justification.

Negative: disapproval, objection, critique, self-critique, blame

[111] Group Material from Democracy: A Project by Group Material, Dia Art Foundation, 1990, p.2. http://www.franklinfurnace.org/research/projects/flow/gpmat/gpmattf.html

[iv] Group Material from Democracy: A Project by Group Material, Dia Art Foundation, 1990, p.2. http://www.franklinfurnace.org/research/projects/flow/gpmat/gpmattf.html

[v] http://www.bampfa.berkeley.edu/exhibition/132

[vi] http://www.guerrillagirls.com/posters/getnakedupdate.shtml

[vii] http://www.christies.com/LotFinder/lot_details.aspx?intObjectID=5101408“

[viii] http://www.businessweek.com/innovate/content/aug2006/id20060804_290886.htm

[ix] http://digitallabz.com/blogs/11-examples-of-viral-marketing-campaigns.html

REFERENCES

Acconci, V., 2001, Leaving Home; Notes on Insertion into the Public, in F. Matzner, Public Art, München, Hatje Cantz, pp. 38-45.

Armajani, S., 2001 Public Art and the city, in F. Matzner, Public Art, München, Hatje Cantz, pp. 96-104.

Cattani. A., 2008, Public Art: from the Site specific to the People Specific, in Proceedings of the Conference Arts Culture and the Public Spere, Expressive and Instrumental Values in Economic and Sociological Perspectives, Venezia, IUAV.

Cattani, A., 2009, Advertising and Rhetoric, Milano, Lupetti.

Danto, A., 1981, The transfiguration of the commonplace, Harvard University Press.

De Vries, H., 2001, What, Why, Wherefore, in F. Matzner, Public Art, München, Hatje Cantz, pp. 118-123.

Eemeren, F. H. Van & Houtlosser Peter 2005, Argumentation in practice, Amsterdam, John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Eemeren, F.H. van, 2002, Advances in Pragma-Dialectics, Amsterdam, Sic Sat.

Eemeren, F.H. van, Grootendorst R., 1992, Argumentation, Communication, and fallacies, Hillsdale – New Jersey, Lea.

Hauser, G., 2005, in Eemeren, F. H. van & Houtlosser Peter 2005, Argumentation in practice, Amsterdam, John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Kuball, M., 2001, And, it’s a pleasure. The laboratory of Public Space, in F. Matzner, a cura, Public Art, München, Hatje Cantz, pp. 454-461.

Lassen, I., Strunck, J., Vestergaard, T., 2006, Mediating Ideology in Text and Image, Amsterdam\Philadelphia, John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Levinson, J. C., Hanley, Paul R.J., 2007, Guerrilla marketing. Mente, persuasione, mercato, Rome, Castelvecchi.

Lucas, G., Dorrian M., 2006, Guerrilla Advertising. Unconventional brand communication, London, Laurence King.

Matzner, F., 2001, Public Art, München, Hatje Cantz.

Mirzoeff, N., 1999, Visual Culture, London, New York, Routledge.

Perelman, C., Tyteca, O., 1989, Treaty of argumentation, Turin, Einaudi.

Sacco, P., 2006, Public Art and Suburbs, Economy of Culture, Bologna, Il Mulino.

Stati, S., 1990, Le Transphrastique, Paris, Puf.

Twitchell, J.B., 1996, Adcult in the Usa, New York, Columbia University Press.