ISSA Proceedings 2010 – Definitions And Facts. Arguing About The Definition Of Health.

1. Introduction

1. Introduction

The aim of this contribution is to explore the role and use of so called persuasive definitions in the field of health and, more specifically, within the longstanding dispute about the definition of health. By persuasive definitions we mean those definitions that, while describing the meaning of a concept, attempt to support some views about that concept (Stevenson 1938; Schiappa 1993; Schiappa 1993; Macagno & Walton 2008a and 2008b; Kublikowsi 2009).

In our analysis, we will address some limitations in Edward Schiappa’s views on this issue. Schiappa defends a rhetorical practice of definition by claiming that persuasive definitions that attempt to grasp the essence of facts are dysfunctional and should be avoided (Schiappa 1993, p. 412). By exploring the argumentative exchange around the definitions of health, we will show that if, indeed, these definitions have been constructed to promote a certain way of thinking about health more than to look at the essence of health, they don’t lose sight of facts. Moreover, precisely their link to facts and their evaluation in light of facts by the scientific community are argumentative moves that promoted the development of important instruments to better understand, describe and measure health, e.g. WHO Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) that we will describe below.

2. The use of definition in argumentation

According to Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca (1969, p. 213), definitions in argumentation can be involved in two phases of the reasoning process: they can be supported or validated as conclusions of arguments; they themselves can be the premises of arguments. The distinction between argumentation ‘about definition’ and argumentation ‘from definition’ was already clear in the classical theory of argumentation (Rubinelli 2009, pp. 3-29). An argumentation about a definition is designed to arrive at a definition. Reaching a definition of a concept is the end point of a discussion, as in the Platonic dialogues. Definitions are the standpoint to be established or refuted through argumentation. Thus, for example, one of Aristotle’s topoi instructs on how to refute a definition by showing that a species has been assigned as a differentia:

Again, you must see whether he has assigned the species as a differentia, as do those who define ‘contumely’ as ‘insolence combined with scoffing’; for scoffing is a kind of insolence, and so scoffing is not a differentia but a species. (Aristotle, Topics H, 144a 5-9. Transl. by Forster (1960))

But a definition can also be the starting point of a discussion, and functions as a premise to support or refute a standpoint. So, for example, we use the definition of a subject or a predicate to show the incompatibility of the predication. To quote another Aristotelian example, to see if it is possible to wrong a god, you must ask, what does ‘wrong’ mean? For if it means ‘to harm wittingly’, it is obvious that it is impossible for a god to be wronged, for it is impossible for god to be harmed (Topics B, 109b 30-110a 1).

This paper mainly focuses on the use of definitions as standpoints of argumentations.

Perelman and Olbrecht-Tyteca (1969, p. 448) argued that these definitions function as claims about how part of the world should be conceptualized; how part of the world is. According to them, the speaker who constructs these definitions «will generally claim to have isolated the single, true meaning of the concept, or at least the only reasonable meaning corresponding to current usage». Schiappa refuted precisely this idea of a ‘true meaning of the concept’.

In 1993, he discussed the nature of those persuasive definitions that are used rhetorically to the detriment of what, since Plato’s time, are presented as ‘real definition’. In particular, real definitions refer to the efforts to define things rather than words. They are concerned with what the defining qualities of the referent ‘really’ and ‘objectively’ are (what corresponds to Socrates’ question: what is X?). The idea that a real definition of a word depicts what is ‘essential’ about the word’s referent is at the basis of what Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca (1969, 00. 411-459) describe as dissociation: an arguer’s strategy to dissect a unified idea into two concepts; one of which is seen as more valuable than the other. An arguer uses this pair by claiming that one definition is “better” or “more realistic”, the other is “worse” or “mere appearance”. According to Schiappa (1993, p. 404), there are two problems with this type of ‘essentialism’: firstly, the language of essentialism prevents understanding of important social needs involved with defining; secondly, dissociations are based on an untenable theory of language and meaning.

In line with the remarks by Robinson (1954), Schiappa concluded that real definitions do not and cannot describe things-in-themselves, and should be abandoned.

Our main claim is that in the field of health avoiding real definition is dangerous from a healthcare point of view. An analysis of the definitions of health and their development shows that their link to facts is a prerogative for the achievement of concrete outcomes, e.g. the improvement of health. For sociopolitical, economical and ethical reasons, the restoring of health is a main concern of society. But restoring health involves several aspects that a definition of health must accommodate (Callahan 1973) if we want these aspects to be addressed through concrete treatment actions. Conceptual clarity in thinking about what health ‘in reality’ is is essential so that the notion can be operationalized in the best manner (Salomon et al. 2003). Failures in grasping the essence of health lead to poor description and measurement instruments. These failures can affect the actual treatment of the patient, when assumptions about health are made from a conceptual model that does not take into consideration what matters about health, and what has to be done to improve it. Definitions of health, as pointed out by Steinfels (1973), influence the way of dealing with the situation: notions of health and illness imply answers to three key questions about a given condition: what should we do? who is to do it? how should it be done?

3. Testing definitions. An Aristotelian perspective

For the reasons given above, definitions of health unavoidably face and are faced with factual issues. Indeed, if we analyze the development of the ongoing discussion about the definition of health, we see there an instance of the dialectical debate that Aristotle codified in the Topics when discussing the potential of the method of topoi for testing endoxa. In Topics A 2, 101a 37- 101b 4 we read that the method of topoi:

is useful in connection with the ultimate bases of each science; for it is impossible to discuss them at all on the basis of the principles peculiar to the science in question, since the principles are primary in relation to everything else, and it is necessary to deal with them through the generally accepted opinions (endoxa) on each point. This process belongs peculiarly, and most appropriately, to dialectic; for, being of the nature of an investigation, it lies along the path to the principles of all methods of inquiry.

As discussed elsewhere (Rubinelli 2009, p. 43-47), the primary principles of science must be addressed on the basis of endoxa, those propositions that are plausible and reputable because they are granted by all of the majority, or by the wise or by scientists (Aristotle’s Topics A 1, 100b 21-23). Topoi are a method for testing endoxa, and the test is performed by looking at the world and searching for essential characteristics of things that can either confirm or refute the endoxa under analysis. Topoi help confirming or finding out contradictions in people’s claims and, in the case of the definition of health (a primary principle for health sciences), by looking at whether endoxa describing what health is about contrast with evidence found in the reality.

Definitions of health are constantly tested dialectically and we can witness several attempts to refine definitions that, even if they have a persuasive power, do not exhaustively account for facts. Below, we shall focus on the two definitions of health that have captured most of institutional and academic attention.

The first definition refers to the so-called biomedical model of medicine. The core idea behind this model probably goes back to the mind-body dualism firmly established under the imprimatur of the Church. Classical science readily fostered the notion of the body as a machine, of disease as the consequence of breakdown of the machine, and of the doctor’s task as repair of the machine. Thus, the scientific approach to disease began by focusing in a fractional-analytic way on biological (somatic) processes. The biomedical model has molecular biology as its basic scientific discipline. It assumes disease to be fully accounted for by deviations from the norm of measurable biological (somatic) variables (Engel 1977). The medical model descriptively suggests an idea of health as the absence of disease.

The persuasive connotation of this definition is clear. The biomedical model codified in the society a specific way of thinking about health with a main focus on its anatomical and structural characteristics. And again, as is typical of a persuasive concept, it offered a pragmatic understanding of health that focuses on the most measurable and manageable aspects of health.

Yet, it is a persuasive definition that was not developed without a look at health as a fact. Its core idea rests on the empirically verifiable assumption that restoring health implies first and foremost treating the health condition and limiting its negative impact at the mental or physical level.

What the biomedical model does not fully acknowledge is a consideration for other essential aspects around health that do matter in terms of improving functioning. And this lack of consideration was made explicit by those scientists who attempted to refine the idea of health (Engel 1977).

By looking from an argumentative perspective, the refinement of this definition was conducted by demolishing the following fallacy of denying the antecedent:

If disease, then no health

No disease

Health

If ‘health’ is ‘absence of disease’, by modus tollens it follows that the ‘presence of disease’ indicates ‘no health’. The inference from this assumption is that successfully treating a disease by ameliorating an abnormal condition of the body organism restores health. This inference can be more or less granted in dealing with cases where the health conditions can be completely eliminated by a specific treatment. But in cases where the health condition becomes chronic the situation is different. In those cases, the physical or mental impairments cannot be cured completely. These impairments limit the activities that individuals can perform. In order to improve the health conditions of those people, these limitations need to be considered. Thus, for instance, there will be cases where the restoring of individual levels of functioning at the physical level will need to be complemented with interventions in the environment (see, for instance, the restructuring of a house to accommodate the needs of a patient on a wheelchair). But this environmental component must be acknowledged as a possible factor that can impact on functioning in order for the health system to address it.

In addition to this, epidemiological data show that treatment directed only at the biochemical abnormality does not necessarily restore the patient to health even if there is evidence of corrections or major alleviations of the abnormality. Other factors play a role in restoring health, even in the face of biochemical recovery. Thus, for instance, it has been proven by several studies in doctor-patient communication that the behavior of the physician and the relationship between patient and physician powerfully influence therapeutic outcome for better or for worse. Thus, for instance, involving patients in treatment and management decisions has been proven to improve the appropriateness, safety and outcome of care (Stewart 1995; Collins et al. 2007 pp. 4-6). Again, as Engel explained (1977, pp. 131-132), insulin requirements of a diabetic patient may directly affect underlying biochemical processes, the latter by virtue of interactions between psycho-physiological reactions and biochemical processes implicated in the disease: insulin requirements may fluctuate significantly depending on how the patient perceives his relationship with his doctor. Doctor-patient communication is not, strictly speaking, a component of health, but it is a health-related domain in the sense that it can impact on health.

A definition of health must, thus, be broad enough to allow consideration for aspects other than the health conditions that might affect health at the mind and body level.

The limitations of thinking about health in terms of the health conditions alone were explicitly addressed by the members of the United Nations that in 1948 – when they ratified the creation of the World Health Organization – presented a new definition of health as:

«a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease.» (WHO 2006)

This was, clearly, another persuasive definition that aimed at spreading in the society a certain way of thinking about health. It did not capture the essence of health. That health does not equal well-being is intuitively obvious. Also, setting the state of ‘complete’ well-being as the standard of health would make all of us chronically ill. How often can we claim to be in a state of complete well-being? And, if we are in such a state, how long does it last? (Callahan 1973; Jadad and O’Grady 2008) Yet, WHO definition was created by thinking empirically, in terms of the objective limitations of the biomedical perspective. Thus, we shall see below, even if this definition was and is still highly criticized, it prepared the ground for the development of more refined instruments for the description of health.

4. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF)

The main criticism of the WHO definition of health presented above was inspired by the evidence that it conflicts with some facts. As Smith (2008) ironically comments, it is a definition that would leave most of us unhealthy all the time. From an operational point of view the idea that health implies ‘completeness’ is clearly impracticable, unattainable and not measurable.

Moreover, the claim of this definition instantiated a dialectical debate based on the application of a specific topos, namely that for dealing with things which are said to be the same. We read in Aristotle’s Topics:

[to refute similarity among two things] you must examine them from the point of view of their ‘accidents’ (…) for any accident of the one must also be an accident of the other (…) For, if there is any discrepancy on these points, obviously they are not the same. (Topics H 1, 152a 33-37)

The WHO definition equals health with well-being. But if we look at the contrary of health, namely, ‘disease’ (a term that includes injuries, disorders, aging, stress etc.), we see that while disease is incompatible with physical health (even if a person does not feel unhealthy, diseases affect body structures or functions at some level), a certain degree of disease is absolutely compatible with well-being. A clear example of the distinction between health and well-being is explained by the disability paradox: many people who have serious and persisting disabilities report good or high level of well-being (Albrecht and Devlieger 1999). The health of those people is affected by the disease, but not so much their well-being. Thus, according to Aristotle’s topos, the two things are not the same.

Another topos applied in the dialectical testing of the WHO definition is found in the passage of the Topics where Aristotle suggests to demolish claims by looking at their consequences (the so called argumentum ad consequentiam, Walton 1999):

You must examine as regards the subject in hand what it is on the existence of which the existence of the subject depends (…) for destructive purposes, we must examine what exists if the subject exists; for if we show that what is consequent upon the subject does not exist, then we shall have demolished the subject. (Topics B 4, 111b 17-13)

This topos has been applied by looking at the unacceptable consequences for society of equating health and well-being. More specifically, Callahan (1973, p. 80) noted that this equation «would turn the problem of human happiness into a medical problem, to be dealt with by scientific means». The medical profession would be the gate-keeper for happiness and well-being. These consequences are unacceptable, insofar as there is no evidence that medicine can ultimately restore happiness or can advice on how to deal with happiness.

But despite these lines of criticism, the appeal of the WHO definition to the ‘not merely absence of disease’ promoted a different view on health that, without diminishing the value of the biomedical perspective, complemented it. Indeed, thanks to this definition and its testing, a crucial assumption about health was made, namely that there must be consideration for both the actual health states in which people live and factors other than the health conditions that can influence those conditions (Salomon et al. 2003). These factors must be conceptualized and taken into consideration for healthcare purposes.

This assumption was translated in the creation of an instrument to describe health that could contextualize health in a broader context, namely the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF, WHO 2001).

The ICF allows us to classify a person’s lived experience of the health condition in terms of levels of functioning that are directly linked to health condition as well as levels of functioning associated with health conditions that result from interactions between the health condition and personal and environmental contextual factors.

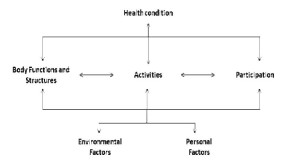

Endorsed by the World Health Assembly in 2001, it focuses on the concept of ‘functioning’ and operationalizes health in terms of etiology – neutral dimensions of individual experience. The ICF provides categories to describe individual levels of functioning at the body, person and societal levels, and what can influence functioning. It has two parts, each with two components. Part one (Functioning and Disability) covers: 1) body functions, i.e. the physiological functions of body systems, and body structures; i.e. the anatomical parts of the body; 2) activities, i.e. the execution of tasks or actions by an individual, and participation, i.e. individuals’ involvement in a life situation. Part two (Contextual Factors) covers: 1) environmental factors that make up the physical, social and attitudinal environment in which people live and conduct their lives; 2) personal factors or the particular personal background of an individual’s life and living, e.g. gender, race, age and habit. Functioning in a specific domain is an interaction or complex relationship between the health condition and contextual factors, according to the following scheme (ICF, WHO 2001, p. 18) (Figure 1):

Functioning mirrors the ‘lived experience’ of the individual whose life and activities are affected by a health condition. The ICF model of functioning and disability makes it possible to describe the difficulties that individuals may face in all aspects of their life (Leonardi and Martinuzzi 2009). As we have recently claimed (Rubinelli et al. 2010), the ICF model of functioning offers an optimal operationalization of health.

The implementation of the ICF as an instrument to describe health has been proven to advance health practice for the improvement of individual health. To quote an important instance of this improvement, we can think about the use of the ICF in rehabilitation. Rehabilitation is the core strategy for the medical specialty known as Physican and Rehabilitation Medicine (PRM), a major strategy for the rehabilitation professions and a relevant strategy for other medical specialties and health professions, service providers and payers in the health section. When based on the biomedical model, rehabilitation is seen as a process of active change by which a person with disability is enabled to achieve the knowledge and skills needed to achieve optimal physical, psychological and social functioning. According to this view, it is the individual and not the environment who has to change or who has ‘to do the work’. The biomedical perspective is of utmost importance to enable people to achieve optimal capacity. Yet, it is equally important to enable relevant persons in the immediate environment encompassing family, peers and employers, to remove environmental barriers and to create a facilitating larger physical and social environment, to build on and to strengthen personal resources and to develop performance in the interaction with the environment (Stucki et al. 2007). The targets for interventions outside the health sector are mainly within the environmental component of the ICF. While these interventions may be provided by, or in co-ordination with, sectors outside health, their common goal is to improve functioning of people with health conditions.

As illustrated by Rauch et al. (2008), the ICF facilitates the description of a patient’s functioning. Since the description of a functioning state can be very complex in many health conditions and clinical situations taking into account a multitude of limitations in all aspects of functioning and the interacting contextual factors, multidisciplinary team work with comprehensive expertise in varying areas of functioning is required. The ICF provide a common language and a structured documentation form which can be used commonly across disciplines. Moreover, the ICF supports the detection of the important patient’s perspective. Healthcare providers are often faced with the patient’s subjective perspective of functioning and the corresponding negative and positive feelings. The use of the ICF can contribute to the active involvement of the patient by suggesting topics of discussion which are relevant in his life with a health condition.

5. Conclusion

Definitions can come out of ideologies. They are often presented to promote a certain way of looking at facts according to the point of view of the person or group of person behind them. But the analysis of the definitions of health shows that their use for healthcare progresses requires attention for the essential characteristics of health. Poor descriptions of health have negative ethical, socio-political and economical implications. Attempts to be persuasive, in this sense, never ignore facts and cannot escape the test in light of facts. As Charles Peirce would probably conclude at this point: “Facts are hard things which do not consist in my thinking and so and so, but stand unmoved by whatever you or I any men or generations of men may opine about them”. We can decide that health is whatever we like it to be. But to make patients feel better, we cannot invent a definition of health.

REFERENCES

Albrecht, G.L., & Devlieger, P.J. (1999). The disability paradox: high quality of life against all adds. Social Science and Medicine, 48(8), 977-988.

Callahan, D. (1973). The WHO definition of health. The Hastings Center Studies 1, 77-87.

Collins, S., Britten, N., Ruusuvuori, J., & Thompson, A. (2007). Patient participation in healthcare consultations: qualitative perspectives. Berkshire: Open University Press.

Engel, G.L. (1977). The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science, 196(4286), 129–136

Forster, E.S. (tr.) (1969). Aristotle. Topics. Cambridge: Loeb Classical Library.

Jadad, A.R., & O’Grady, L. (2008). How should health be defined? British Medical Journal 337: a2900.

Kublikowski, R. (2009). Definition within the structure of argumentation. Studies in Logic, Grammar and Rhetoric, 16(29), 229-244.

Leonardi, M., & Martinuzzi, A. (2009). ICF and ICF-CY for an innovative holistic approach to persons with chronic conditions. Disability and Rehabilitation, 31(S1): S83-87.

Macagno, F., & Walton, D. (2008a). Persuasive definitions: values, meanings and implicit disagreements. Informal Logic, 28(3), 203-228.

Macagno, F., & Walton, D. (2008b). The argumentative structure of persuasive definitions. Ethical Theory and Moral Practice, 11(5), 525-549.

Perelman, C., & Olbrechts-Tyteca, L. (1969). The New Rhetoric. J. Wilkinson and P. Weaver (tr.), University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame. Originally published in 1958 as La Nouvelle Rhétorique: Traité de l’Argumentation, Paris : Presses Universitaires de France.

Rauch, A., Cieza, A., & Stucki, G. (2008). How to apply the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health for rehabilitation management in clinical practice. European Journal of Physical Rehabilitation Medicine,44(3), 329-342.

Robinson, R. (1954). Definition. Oxford: Clarendon.

Rubinelli, S. (2009). Ars Topica. The Classical Technique of Constructing Arguments from Aristotle to Cicero. Dordrecht: Springer.

Rubinelli, S., Bickenbach, J., & Stucki, G. Health according to the ICF model of functioning. BMJ Rapid Response, July 12 2010. Available at: http://www.bmj.com/cgi/eletters?lookup=by_date&days=2#238750

Salomon, J. A., Mathers, C.D., Chatterji, S., Sadana, R., Üstün, T. B., & Murray, C.J.L. (2003). Quantifying individual levels of health: definitions, concepts, and measurement issues. In C. Murray & D. Evans (Eds.), Health Systems Performance Assessment. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Schiappa, E. (1993). Arguing about definitions. Argumentation, 7(4), 403-417.

Smith, R. (2008). The end of disease and the beginning of health. BMJ Group blogs. Available at: http://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2008/07/08/richard-smith-the-end-of-disease-and-the-beginning-of-health/.

Steinfels, P. (1973). The concept of health. The Hastings Center Studies 1, 3-88.

Stevensen, C.L. (1938). Persuasive definitions. Mind, 47(187), 331-350.

Stewart, M.A. (1995). Effective physician-patient communication and health outcome: a review. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 152(9), 1423-1433.

Stucki, G., Cieza, A., & Melvin, J. (2007). The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: a unifying model for the conceptual description of the rehabilitation strategy. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 39(4), 279-285.

Walton, D. (1999). Historical origins of argumentum ad consequentiam. Argumentation 13, 251-264.

WHO. Constitution of the World Health Organization. 2006. Available at: www.who.int/governance/eb/who_constitution_en.pdf.