ISSA Proceedings 2010 – Reported Argumentation In Financial News Articles: Problems Of Reconstruction

1. Introduction

In this paper we explore the argumentative function of reported speech in economic-financial newspaper articles. The present research is based on a corpus of articles of the three main daily Italian economic-financial newspapers: Il Sole 24 Ore, Italia Oggi and MF/Milano Finanza. Why are we interested in studying the relationship between reported speech and argumentative function of economic-financial news? The analysis of economic-financial newspaper articles previously carried out shows that the predictive speech act occupies a dominant position in the discourse structure of economic financial news (Miecznikowski, Rocci, and Zlatkova in Press). Being clearly oriented towards predicting events, the information demand in the journalistic discourse domain of finance differs significantly from other domains, such as editorials, sports, crime, whose informational interest lies in narrating or commenting past events.

The reader wants to know not what has happened, but also, more importantly, what is going to happen. The analysis also showed that the predictive speech acts and their supporting arguments are sometimes attributed to unnamed, but more often to named sources, such as financial analysts, money managers, bankers. Being geared towards the decision making of investors, financial discourse is overtly or covertly argumentative. These semantic and pragmatic features of economic-financial discourse make this genre particularly interesting for investigation. The frequent use of reported speech in this genre poses a challenge to argumentative reconstruction, because it is difficult to attribute the role of protagonist to the journalist who often seems to use reported speech strategically to avoid his/her personal commitment to either the standpoint or the argument. However, in this paper we argue that the distinction between different types of reported discourses and the distinction between different forms introducing them provide important cues for determining the functions of the reported segments in the journalist’s argumentation and ascertaining to what extent the journalist is committed personally to the stated claim.

2. Types of reported segment

For the present research we adopt a broad definition of reported speech that is a quotation of another’s discourse, the presence of another person’s words in the author’s discourse (Calaresu 2004, Smirnova 2009). The analysis of the corpus showed that the reported segment can be of two types: I) it is used to report an opinion; II) it puts forward an argumentation. The reported segment used to report an opinion can perform both non–argumentative and argumentative function. In the case of non-argumentative use, the journalist simply reports an opinion maintaining a clear distance with respect to what is said as illustrated in example 1.

1. Altre potenziali prede secondo Jason Goldberg, analista bancario di Lehman Brothers, sarebbero istituti cinesi, brasiliani, coreani e dell’Europa dell’Est, a cominciare dalla Russia. (Il Sole 24 Ore, 05.04.2006, doc. 9)

Other potential targets, according to Jason Goldberg, a banking analyst at Lehman Brothers, are Chinese, Brazilian, Korean, and Eastern European financial institutions, in addition to the Russian ones.

Here the journalist reports the opinion of the banking analyst Jason Goldberg about the potential financial institutions, without taking position or commenting on it. There are neither subjectifiers[i] in the co-text[ii], which indicate the stance of the journalist towards the expressed opinion, nor other markers by means of which we can infer the journalist’s position. Therefore, we cannot attribute the role of protagonist to the journalist. In such cases, the reporting of an opinion has merely informative and not argumentative function. Moreover, the choice of reported speech indicates the distance of the journalist from what is said, and what he/she undertakes no attempt to defend. In this example, the reported speech is introduced by an indirect glossed form of reported speech, analysed in the literature (Calaresu 2004, p.163) as a form expressing a clear distance of the speaker/writer with respect to the reported utterance. This form is characterized by an introductor which performs the function of “gloss” inside or on the margin of the citation (“Other potential targets, according to Jason Goldberg…”). Indirect glossed form of reported speech creates an unexpected dissociation between the author of the original discourse and who reports it. In fact, in the case of indirect glossed speech, a segment of discourse is interrupted by the introductor, signalling that the responsibility for the utterance is somebody else’s.

Beyond the non-argumentative use, the reported segment can perform an argumentative function as a basic argument from authority, as illustrated in example 2.

2. Il mercato italiano del vino sta uscendo dalla crisi. Lo afferma Vinitaly, il salone dei vini e distillati che aprirà le sue porte a Verona dal 6 al 10 aprile. (Italia Oggi, April 1, 2006 doc. 628)

The Italian wine market is overcoming the crisis. This was affirmed by Vinitaly, the salon of wines and spirits which will be open from April 6th to 10th.

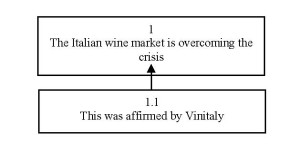

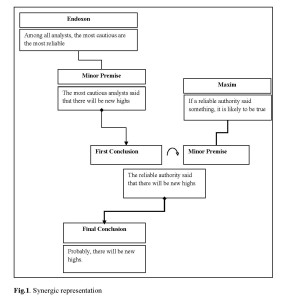

Following the method suggested by Pragma–Dialectics (cf. Van Eemeren, Grootendorst, Snoeck Henkemans 2002), we will represent the argumentative structure graphically after every discussed example by showing which arguments support the standpoint and how these arguments are organized and combined.`(Figure 1)

The standpoint The Italian wine market is overcoming the crisis is supported by evoking the authority of Vinitaly. As we can see from the graphical representation, we have a case of single argumentation (Eemeren & Grootendorst 1992), with just one argument supporting the advanced standpoint. It is worth noticing that the reported segment is introduced by the anaphoric pronoun lo (“this”). In linguistics, the term anaphora is used to refer with a pronoun to an object that has already been introduced into the discourse by some other linguistic construction. In other words anaphora is the relationship between two linguistic elements where the interpretation of the one of the elements (called the anaphora) requires the interpretation of the other (called the antecedent) (Bazzanella 2005, p. 79). In our example lo (“this”) refers back to the situation described in the previous sentence, i.e. that The Italian wine market is overcoming the crisis. If we compare this way of introducing reported speech with a “classical” indirect form of reported speech: Vinitaly has affirmed that the Italian wine market is overcoming the crisis, we clearly notice the different position of the introductor. In the case of anaphoric use the introductor is postponed Lo afferma Vinitaly (“This was affirmed by Vinitaly”), whereas in the case of the classical indirect form of reported speech, the introductor precedes: Vinitaly has affirmed that […]. The rhetorical effect of the different position of the introductor has been widely discussed in the literature (Calaresu 2004). The strategy of the postponed introductor has the rhetorical function of a surprise effect; it means that the reader has to reinterpret what he has just read as the discourse of someone else, other than the journalist. The above-mentioned case differs significantly from cases where the introductor is put at the beginning and the reader immediately interprets the discourse as reported. In our corpus the use of the postponed introductor to introduce the argument from authority is frequently encountered in cases where the journalist endorses the reported opinion.

It emerges from the corpus analysis that the argument from authority can also be part of a complex structure used to support a standpoint advanced by the journalist as illustrated in example 3. We make a clear distinction between examples 2, where the journalist endorses what is said and examples such as example 3, where the journalist advances his/her own standpoint using an argument from authority to support it.

3. E a quel punto, è ipotizzabile – la maggioranza degli analisti tecnici e fondamentali è d’accordo – l’avvio di una fase laterale. Per questo gli investitori dovrebbero utilizzare i prossimi top per prendere profitto e iniziare la ristrutturazione dei portafogli. (Il Sole 25 Ore, April 10, doc. 170)

At this point, it is presumable that a sideway phase is about to start – the majority of the technical and fundamental analysts agree on that. For this reason, investors should use the next peak to make a profit and begin reorganizing their portfolios.

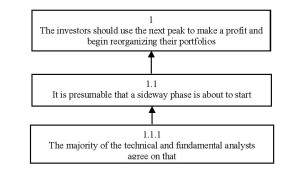

The argumentative structure of the example can be reconstructed as follows (Figure 2):

The standpoint advanced in example 3 is a directive speech act of recommendation: The investors should use the next peak to make a profit and begin reorganizing their portfolios. The standpoint is neither attributed to financial analysts nor to other sources. It is advanced by the journalist, so we can attribute to him/her the role of protagonist. It is worth noticing that the phrase per questo (“for this reason”), preceding the recommendation, is a typical argumentative indicator of the advancing of a standpoint. This standpoint is supported by subordinatively compound argumentation, where the defence itself is supported by a longer or shorter series of “vertically linked” single argumentation. Each of the arguments in the chain contributes to the defence of the standpoint by supporting the argument immediately above, and only the series as a whole contributes to its conclusive defence (Eemeren & Grootendorst 1992). In example 3, the specific standpoint: the investors should use the next peak to make a profit and begin reorganizing their portfolios is supported by an argument it is presumable that a lateral phase is about to start which serves as a substandpoint and in its turn is defended by an argument from authority the majority of the technical and fundamental analysts agree on that. It is worth noticing that the force of the argument from authority is further enhanced by the argument from consensus between technical and fundamental analysts, who usually are two divergent authorities. Technical and fundamental analyses refer to two different and often polemically contrasted stock-picking methodologies used for researching and forecasting the future growth trends of stocks.

Analysis of our corpus showed that, to enhance the credibility of the source, the journalist in economic-financial newspaper articles uses either professional characteristics of the source in order to present it as an authority in the domain, thus removing any possible doubts about his reliability (“Stefano Zoffoli, strategist of Julius Baer asset management […]” MF, April 14, 2006, doc. 24; “Adolfo Guzzini, president of Guzzini, turnover of 170 million Euros […]” Il Sole 24 Ore, April 25, 2006, doc.101) or he/she uses the argument from consensus to convince the reader about the credibility of what is said (“Even the most cautious analysts said that […]” Il Sole 24 Ore, April 20, 2006, doc. 27; “The majority of the technical and fundamental analysts agree on that” Il Sole 25 Ore, April 10, doc. 170). The combination of both strategies is also possible.

So far, we have discussed cases where the reported segment is used to report an opinion. Now we move to cases where the reported segment contains argumentation. Analogously to the cases discussed previously, also in the cases where the reported segment contains argumentation we distinguish between non-argumentative and argumentative uses. In the case of a non – argumentative use the journalist simply reports an argumentation, distancing himself from it as illustrated in example 4

4. Morgan Stanley sconsiglia invece di investire nel mercato del mattone reduce da quattro anni di crescita eccezionale. Il comparto è già in una chiara fase di frenata (Il Sole 24 Ore, April 2, 2006, doc. 47)

Morgan Stanley advised not to invest in the brick market after four years of exceptional growth. The sector is in clearly slowing down.

Here the journalist reports not only the advice of Morgan Stanley not to invest in the brick market but also the supporting argumentation that the sector is clearly slowing down. Since the journalist distances himself from the reported advice as well as from the argumentation supporting it, the role of protagonist cannot be attributed to him.

Differently from example 4, in example 5, the journalist endorses the reported argument giving rise to an argument from authority including the reported argumentation of the authority. Since the journalist endorses the reported argumentation the role of protagonist can be attributed to him.

5. Meno rosee le prospettive per i consumatori: secondo Browne il prezzo della benzina non potrà che salire data l’impennata del greggio. (Il Sole 24 Ore, April 26, 2006, doc.22)

The economic outlook for consumers is less bright. According to Browne, the

price of petroleum can only rise given the steep rise of crude oil.

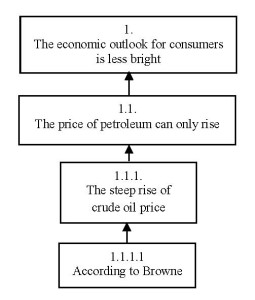

Argumentatively, the standpoint the economic outlook for consumers is less bright is supported by a complex structure of argument from authority including the entire line of reasoning advanced by Browne. As has been argued by Smirnova (2009) in her paper on the argumentative function of reported speech in British newspapers, cases of pure appeal to authority are rare. In the majority of cases, we have a combination of an argument from authority with another type of argument. In this example the Brown’s authority supports the causal connection between the price of crude oil and the price of petroleum established in the major premise if the price in crude oil rises, then the price of petroleum rises (Figure 3).

Differently from example 5, where the journalist only endorses the reported standpoint, in example 6, the journalist advances his/her own standpoint and supports it by using a complex structure where the reported segment contains argumentation. We will discuss this example more in detail to demonstrate the contribution of the reconstruction of the argumentative scheme proposed by the Argumentum Model of Topics (see below) to the reconstruction of the argument structure.

6. Anche gli analisti più cauti puntano su nuovi rialzi: John Reade dell’UBS, li ritiene molto probabili, e Simon Weeks di ScotiaMocatta, nota che “sono in pochi a vendere” e ciò rende molto vicino il traguardo di 640$. (Il Sole 24 Ore, April 20, doc. 27)

Even the most cautious analysts predict new highs. John Reade from UBS, considers them very probable, and Simon Weeks of ScotiaMocatta, noticed that “only few people sell”, and this makes the goal of $ 640 very close.

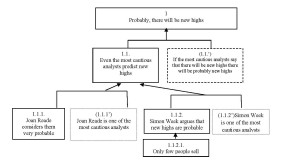

The argumentative structure of the example can be reconstructed as follows (Figure 4):

The standpoint probably there will be new highs is supported by coordinative argumentation with an unexpressed major premise: If the most cautious analysts say that there will be new highs there will be probably new highs. The explicit premise even the most cautious analysts say that there will be new highs is supported by two independent arguments from authority, the first one is: John Reade considers them very probable and the unexpressed premise: Joan Reade is one of the most cautious analysts and the second one is: Simon Week argues that new highs are probable and the unexpressed premise: Simon Week is one of the most cautious analysts. In the second argument from authority, we have a reported argumentation of the source, as we can see from the graphical representation above: the reason why Simon Week argues that new highs are probable is based on economic causality that only few people sell. In order to explore in depth the relationship between standpoint and argument we use the Argumentum Model of Topics (henceforth AMT) , developed at the Institute of Linguistics and Semiotics, University of Lugano, in particular by Eddo Rigotti and Sara Greco-Morasso (Rigotti 2006, 2009a, 2009b, Rigotti and Greco-Morasso 2006). The AMT represents the reasoning chain underlying an argument and highlights both the logic and the pragmatic/contextual components of the argument scheme. It is made up of two syllogisms: one is the endoxical syllogism whose major premise is an endoxon, and the other is the topical syllogism, whose major premise is a maxim. A maxim is an implication of the form p->q, generated by a locus and which gives rise to an inferential process. An argumentative scheme (locus) from authority emerges from the reconstruction presented above. Using the AMT we build the “synergic” representation of an argument from authority (see figure 1 below) which allows us to distinguish, within the inferential structure of the argument, the two components mentioned previously. The specific standpoint here is probably there will be new highs. The maxim if a reliable authority said something, it is likely to be true is directly engendered from the locus from authority. In order for this maxim to generate the final conclusion, which coincides with the standpoint to be supported, the following minor premise is needed: the reliable authority said that there will be new highs. Such a premise however is not self-evident; it needs itself to be backed by another syllogistic reasoning, in this case anchored in an endoxon: Among all analysts, the most cautious ones are the most reliable. The datum, which is the factual statement constituting the minor premise of the endoxical syllogism is, the most cautious analysts, said that there will be new highs. This leads to the conclusion: the reliable authority said that there will be a new highs. This conclusion is “exploited” by the maxim (as indicated by the curved arrow in the diagram) to generate the final conclusion which coincides with the standpoint to be supported: probably, there will be new highs. The two syllogistic reasoning give rise to the complex inferential structure which is represented by a “Y-like structure” within AMT (fig.1). The two syllogisms have distinct, but at the same time complementary functions: the maxim is responsible for the inferential mechanism and defines the law, while the endoxon links the argument to a shared opinion in the community. So, we can say that the topical component ensures the inferential force, whereas the endoxical component ensures the persuasive effectiveness, but if the topical component is not combined with the endoxical component it remains a mere logical mechanism.

From the analysis of example 6 illustrated above, different degrees of complexity emerge:

1. we are dealing with multiplicity of sources – different authorities can be evoked in order to support the standpoint;

2. we can have an addition argument supporting the credibility of the source, e.g. the argument from consensus like in example 6 where the consensus between the less cautions and the most cautious analysts (“even the most cautious analysts say that there will be new highs”) is emphasized in order to boost the credibility of the source itself; and

3. we have the reporting of an entire line of argumentation of the source:

As it has been argued previously in the paper, the strategies of boosting the credibility of the source are highly used by the journalist when he/she endorses the standpoint advanced by the source or when he/she advances his/her own standpoint (Figure 5).

3. Conclusion

This paper explored the function of the reported segment with a particular focus on the journalist’s stance towards the reported statements in order to demonstrate that there is a constellation of indicators providing a sufficient basis for ascertaining to what extent the journalist assumes the role of protagonist, and that in many cases, the argumentative reconstruction is fully justified.

From the analysis carried out, it emerges that reported speech can perform both a non- argumentative and an argumentative function. The reported segment can have a purely informative function: the journalist simply reports an opinion, an argumentation maintaining a clear distance with respect to what is said; in this case he/she is not committed personally to any reported claim. Alternatively, the reported segment can perform an argumentative function. In the case of opinions (I), the journalist advances a standpoint, supported by an argument from authority. The reported segment may a) contain the standpoint itself, formulated by a third party but endorsed by the journalist; b) contain statements considered by the journalist as arguments for a standpoint expressed in his/her own discourse. Analogously, in case (II), the journalist a) either makes the cited speaker utter the entire line of argumentation he/she intends to put forth or b) expresses a standpoint in his/her own words, backed up by the argumentation contained in the cited segment. In both cases, the result is a complex argument from authority, including reported argumentation of different kinds (causal, pragmatic, symptomatic reasoning etc.).

Some correlations have been identified between the function and the form of reported speech. In the case of purely informative function, the reported speech is mostly introduced by an indirect glossed form, analysed in the literature as a form expressing a clear distance of the speaker/writer with respect to the reported utterance. When the reported segment performs an argumentative function, it is often framed by an indirect form with a postponed framing expression. The use of the postponed framing expression is frequently encountered in arguments from authority in which the journalist endorses the reported segment. The relationship between form and function of reported speech will be investigated more in detail in our future work.

NOTES

[i] For the purpose of this paper we are interested in subjectifiers such as boosters (e.g. infatti (‘indeed’), affatto (‘at all’), proprio, davvero (‘really’) and hedges like quasi (‘almost’), un po’ (‘a bit’), più che altro (‘rather’), or emotionally-connotated lexical items.

[ii] Co-text” is a commonly used term in Discourse Analysis. Co-text refers the words or sentences surrounding any piece of written (or spoken) text. (cf. Brown & Yule 1983).

[iii] Argumentative indicators are “words and expressions that may refer to argumentative moves, such as putting forward a standpoint or argumentation. The use of these argumentative indicators is a sign that a particular argumentative move might be in progress, but it does not constitute a decisive pointer” (van Eemeren, Houtlosser& Snoeck –Henkemans 2007:1)4

[iv] A definition of an endoxon is given by Aristotle: “opinions that are accepted by everyone or by the majority, or by the wise man (all of them or the majority, or by the most notable and illustrious of them)” (Topics, 100b.21)

REFERENCES

Bazzanella, C. (2005). Linguistica e Pragmatica del Linguaggio. Roma: Laterza.

Brown, G., & George, Y. (1983). Discourse Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Calaresu, E. (2004). Testuali Parole: la Dimensione Pragmatica e Testuale del Discorso Riportato. Milano: Franco Angeli.

Conte, M – E. (1999). Condizioni di Coreferenza. Ricerche di Linguistica Testuale. Pavia: Edizioni dell’Orso.

Eemeren, F.H. van, & Grootendorst, R. (1992). Argumentation, Communication and Fallacies: a Pragma Dialectical Perspective. Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Eemeren, F.H. van, Grootendorst, R., Jackson, S., & Jacobs, S. (1993). Reconstructing Argumentative Discourse. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press.

Eemeren, F.H.van, & Grootendorst, R. (2004). A Systematic Theory of Argumentation: the Pragma-Dialectical Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Eemeren, F.H.van, Grootendorst, R., & Snoek-Henkemans, F. (2002). Argumentation: Analysis, Evaluation, Presentation. Mahwah: L.Erlbaum.

Eemeren, F.H.van, Houtlosser, P., & Snoeck-Henkemans, F. (2007). Argumentative Indicators in Discourse. A Pragma-Dialectical Study. Dordercht: Springer

Miecznikowski, J., Rocci, A., & Zlatkova, G. (in Press). L’argumentation dans la presse économique et financière italienne. In L. Gautier (Ed.), Les discours de la bourse et de la finance. Forum für Fachsprachen-Forschung. Frank und Timme, Berlin.

Rigotti, E. (2006). Relevance of context-bound loci to topical potential in the argumentation stage. Argumentation, 20 (4), 519–540.

Rigotti E. (2009a). Whether and how classical topics can be revived within contemporary argumentation theory. In: F.H. van Eemeren & B. Garssen (Eds.), Pondering on problems of argumentation (pp.157-178). Dordrecht: Springer.

Rigotti, E. (2009b). Locus a causa finali. In G. Gobber, S. Cantarini, S. Gigada & S. Gilardoni (Eds.), Word meaning in argumentative dialogue (pp.559-577) Special issue of L’analisi linguistica e letteraria 2009/2. Milano: Vita e Pensiero.

Rigotti, E., & Greco- Morasso, S. (2006). Topics: the argument generator. Argumentation for financial communication. Argumentum eLearning module. Retrieved from www.argumentum.ch

Smirnova, A. (2009). Reported speech as an element of argumentative newspaper discourse. Discourse & Communication, 3(1), 79-103.