ISSA Proceedings 2010 – Strategic Manoeuvring In The Case Of The ‘Unworthy Spouse’

1. Introduction

1. Introduction

In research of legal argumentation different aspects of the process of legal justification have been the object of study. Some researchers consider legal justification as a rational activity and for this reason are interested in the rules that should be observed in rational legal discussions. Others consider legal justification as a rhetorical practice and are interested in the way in which judges operate in steering the discussion in the direction that is desirable from the perspective of certain legal goals.

That both aspects of the legal ‘enterprise’, rational dispute resolution and a rhetorical orientation to a particular result through strategic manoeuvring, can also be reconciled is something that has received little attention in research of legal argumentation. The aim of this contribution is to analyse the way in which courts try to reconcile the dialectical goal of resolving the difference of opinion in a rational way with the rhetorical goal of steering the discussion in a particular direction that is desirable from the perspective of a particular development of law.

To this end I shall analyse the strategic manoeuvring in the justification of the Dutch Supreme Court in the famous case of the ‘Unworthy Spouse’ in which a spouse who had murdered his wife claimed his share in the matrimonial community of property. In this case it had to be established whether and on what grounds an exception to article 1:100 of the Dutch Civil Code, that entitles a spouse to his share in the community of property, can be justified. (For an overview of the relevant legal rules see A at the end of this contribution.) The District Court, the Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court all agreed that an exception should be made and they all justified the exception by referring to certain legal principles that can be summarized as ‘crime does not pay’.[i] However, with regard to the exact argumentative role of the legal principles the Supreme Court adopts another position than the other courts but it does not express this position explicitly but presents it in an indirect way as the interpretation of the decision of the Court of Appeal, thereby giving another interpretation of the argumentative role of the legal principles than was originally intended by the Court of Appeal.

In my contribution I shall describe how the Dutch Supreme Court manoeuvres strategically in its role as court of cassation when attributing a different argumentative role to the legal principles than is intended by the Court of Appeal.[ii] I shall explain how the Supreme Court operates strategically in its capacity of court of cassation to promote a particular development of law with respect to the role of legal principles to make an exception to a rule of law.

The central question in the case of the Unworthy Spouse is whether behaviour that can be considered ‘unacceptable from the perspective of a sense of justice’ or ‘repugnant to justice’ must also be considered as unacceptable from the perspective of civil law when there are no existing rules on the basis of which this behaviour can be characterized as unacceptable. In this case the question is whether a spouse (in this case L.) who has murdered his 72 year old wife (mrs. Van Wylick) after 5 weeks of marriage and who has been convicted of murder in a criminal procedure, still has a right to his legal share in the marital community property on the basis of article 1:100 clause 1 (old) of the Dutch Civil Code, and if he does not have such a right how the exception should be justified for this case.

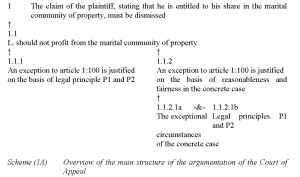

In this case the Court of Appeal decides that L. Does not have a right to his legal share in the marital community of property, making an exception to the rule of 1:00 of the Civil code for this case. The Court of Appeal justifies the exception by referring to two legal principles. The first principle is that he, who deliberately causes the death of someone else, who has benefited and favoured him, should not profit from this favour (P1). The second principle is that one should not profit from the deliberately caused death of someone else (P2). Furthermore the Court of Appeal argues as an ‘obiter dictum’ that also the requirements of reasonableness and fairness would justify making an exception in this particular case. An overview of the main structure of the argumentation of the Court of Appeal is given in scheme 1A.

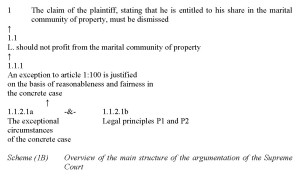

The Supreme Court also answers this question positively. However, the Supreme Court gives another justification of the exception by considering the exception on the basis of reasonableness and fairness as the main argument. An overview of the main structure of the argumentation of the Supreme Court is given in scheme 1B.

As is indicated in scheme IB, in support of this main argument (1.1.1), the Supreme Court mentions the two legal principles in 1.1.2.1b in combination with the exceptional circumstances of this case. In doing so, the Supreme Court departs from the way in which the argument of reasonableness and fairness was presented by the Court of Appeal, i.e. as an obiter dictum (argument 1.1.2), while the two legal principles were presented by the Court of Appeal as the independent main argument 1.1.1.

As is mentioned by the annotator, from the perspective of legal certainty the Supreme Court wants to give a signal to the legal community that general legal principles cannot constitute a reason for making an exception to a legal rule that forms one of the cornerstones of Dutch family law. For this reason the Supreme Court chooses for the ‘safe’ option of restricting the exception to the concrete case by using the derogating function of reasonableness and fairness (which will be introduced in the new article 6:2 of the Civil Code) as the main argumentation 1.1.1 and the legal principles as supporting coordinative argumentation (1.1.2.1b) in combination with the exceptional circumstances (1.1.2.1a).

In this paper I will answer the question what the discussion strategy of the Supreme Court in rejecting the cassation grounds and in changing the argumentative role of the legal principles exactly amounts to from the perspective of the space he has to manoeuvre strategically as a court of cassation. In my analysis of the argumentation strategy of the Supreme Court I use the concept of strategic manoeuvring developed by van Eemeren (2010) and van Eemeren and Houtlosser (2006, 2007). In their approach strategic manoeuvring is conceived as an attempt to reconcile the dialectical goal of resolving a difference of opinion in a reasonable way with the rhetorical goal of steering the resolution in a particular direction.

Van Eemeren and Houtlosser describe a discussion strategy as a methodical design of discussion moves aimed at influencing the result of a particular discussion stage, and the discussion as a whole, in the desired direction. A discussion strategy consists of a systematic, co-ordinated and simultaneous exploitation of the options available in a particular stage of the discussion.

Starting from this conception I shall show that the discussion strategy of the Supreme Court can be described as a consistent effort in the different stages of a critical discussion to steer the discussion in the desired direction.[iii] I characterize the choices the Supreme Court makes in the different stages as a methodical design to steer the outcome of the discussion in the preferred direction, within the boundaries created by the institutional conventions for the discussion in cassation.

2. Analysis of the discussion strategy of the Supreme Court in the case of the ‘Unworthy Spouse’

The aim of the procedure in cassation in the Netherlands is to establish what the law in a particular case should be and how the law should be applied in that case. To this end, in this case the Supreme Court must decide whether the decision of the Court of Appeal is in accordance with the law. For this case this implies that the Supreme Court must investigate whether the rules of law that are applied by the Court of Appeal have been applied correctly.

From this perspective, the dialectical goal of the discussion is to establish whether the protagonist in the case in cassation, the Court of Appeal, has defended its decision successfully against the attacks of the antagonist, the plaintiff in cassation, in light of the common starting points, the rules of law, so that the Court of Appeal can maintain his standpoint, or whether it has been attacked successfully. In this case the Supreme Court tries to reconcile this dialectical goal with the rhetorical goal to steer the discussion in the desired direction, i.e. to convince the audience that application of the rule without making an exception for the concrete case would be unacceptable from the perspective of justice.[iv] To attain this rhetorical goal, the Supreme Court gives a particular interpretation of the system of the law of inheritance by attaching a particular argumentative role to the general legal principles as a legal ground for making an exception to article 1:100 clause 1 of the Civil Code.

To be able to decide that the decision of the Court of Appeal can be maintained, the Supreme Court adopts a particular discussion strategy that consists of a combination of two ‘moves’. First, the Supreme Court wants to be able to decide in the concluding stage of the discussion that the attacks of the plaintiff in cassation L have failed. To realize this aim, in the argumentation stage the Supreme Court must decide that the argumentation of the Court of Appeal is in accordance with the common starting points. To be able to decide this, in the opening stage the Supreme Court must select those starting points that make this evaluation of the argumentation of the Court of Appeal possible.

Second, the Supreme Court wants to give a decision that makes clear that an exception to the rules of family law and the law of inheritance can only be made in very special circumstances. For this reason the Supreme Court must select those starting points that are desirable in light of this view on the development of these branches of law. For this reason, in the opening stage the Supreme Court does not only decide about the role of reasonableness and fairness and certain legal principles as starting points, but also about their argumentative role.

In my analysis I shall explain how this discussion strategy manifests itself in the justification of the decision of the Supreme Court as given in scheme 1B.[v] I shall do this on the basis of the statements of the Supreme Court in the legal considerations 3.2-3.5 (see F at the end of this contribution) that I shall analyse in terms of certain moves in a critical discussion.

The confrontation stage

In this case, the confrontation stage that is intended at realizing the dialectical goal of establishing the difference of opinion, is represented by the cassation grounds formulated by the plaintiff in which he formulates his objections against the decision of the Court of Appeal.[vi] The plaintiff is of the opinion that the Court of Appeal has made a mistake in applying the law by deciding erroneously that certain legal principles apply and by deciding erroneously that it is justified to make an exception to article 1:100 clause 1 of the Civil Code on the basis of reasonableness and fairness. Because the plaintiff determines the content and scope of the difference of opinion, the Supreme Court has no space to manoeuvre strategically in this discussion stage.

The opening stage

In the opening stage the discussion strategy consists of a methodical design of discussion moves aimed at reconciling the dialectical goal of establishing the common starting points with the rhetorical goal of establishing those starting points that are advantageous in view of his final goal of dismissing the appeal in cassation so that the decision of the Court of Appeal can be maintained as well as a particular development of law. The Supreme Court exploits the space he has on the basis of his dialectical role to establish the common legal starting points in a specific way.

In civil procedure in the Netherlands the latitude to establish common legal starting points is specified in article 48 of the Code of Civil Procedure that gives the judge, in this case the Supreme Court, the authority to formulate the legal grounds. In this case it uses this latitude to formulate the legal grounds on the basis of which the exception to article 1:100 clause of the Civil Code can be justified.

The discussion strategy in the opening stage amounts to the following. The Supreme Court chooses those starting points from the topical potential that it needs to steer the result of the opening stage in the desired direction: it chooses those starting points that it needs in the argumentation stage to be able to evaluate the attack of the plaintiff as a failed attack on the argumentation of the Court of Appeal. In doing so the Supreme Court tries to adapt to the preferences of the legal community by taking into account that acknowledging the claim of the plaintiff would be ‘unacceptable for the sense of justice’, as is also stressed by the Advocate-General Langemeijer.

In the old matrimonial property law there was not a rule specifying when someone is unworthy to inherit. To avoid a result that would be unacceptable to the sense of justice therefore the Supreme Court must create a possibility to make an exception to article 1:100 clause 1 of the Civil Code on the basis of certain common legal starting points. The Supreme Court establishes the common starting points by acknowledging that it is possible to make an exception to article 1:100 and it establishes that this exception can be justified on the basis of reasonableness and fairness and on the basis of certain legal principles. In doing so the Supreme Court rebuts the statement of the plaintiff that the exception can not be justified in this way.

Apart from this decision about the status of reasonableness and fairness and the legal principles as common legal starting points, the Supreme Court also decides about the argumentative function of these common starting points. The Supreme Court does this in an implicit way with the following statement in consideration in which it rejects the statements in the cassation grounds of the plaintiff:

‘As appears from the cited formulation, in this context the legal principles only play the role that they have contributed to the decision of the court that the requirements of reasonableness and fairness make the exertion of his right to his share in the inheritance inadmissible. As far as the parts A and B read in legal consideration 5.18 that the court has used these principles as a direct legal ground for denying this right, they lack a factual basis’.[vii] As is shown in the analysis of the argumentation of the Court of Appeal in scheme 1A and the analysis of the argumentation of the Supreme Court in scheme 1B, the Supreme Court gives an interpretation of the argumentation of the Court of Appeal that departs from the way in which the court has intended it. The Supreme Court gives the legal principles the function of subordinate argumentation and does not consider them as independent argumentation as they were presented by the Court of Appeal.

The argumentation stage

In the argumentation stage the discussion strategy consists of a methodical design of discussion moves aimed at giving a positive evaluation of the argumentation of the Court of Appeal in light of the attacks by the plaintiff. In the argumentation stage the Supreme Court tries to reconcile the dialectical goal of establishing the acceptability of the argumentation of the Court of Appeal on the basis of common testing methods in light of the attacks of the plaintiff with the rhetorical goal of evaluating the attacks of the plaintiff in such a way that these attacks fail. To attain this, the Supreme Court uses the common starting points formulated in the opening stage. In doing so, the Supreme Court exploits the space it has within his dialectical task and the authority it has on the basis of the legal rules to evaluate the argumentation in a special way.

The discussion strategy manifests itself first in the statements in the decision in which the Supreme Court decides in legal consideration 3.2 that the grounds of cassation A and B ‘cannot lead to cassation’ because they ‘lack interest’, ‘lack a factual basis’ and ‘depart from a wrong conception of the law’. The strategy manifests itself second in the decision in legal consideration 3.3 cited above that the statement about the exception on the basis of reasonableness and fairness from part C is wrong.

These decisions imply that the attack of the plaintiff (in cassation grounds A and B) on argumentation line 1.1 of the Court of Appeal has failed because the legal principles do exist. The attack (in cassation ground C) on argumentation line 1.2 also fails because the Supreme Court decides that the possibility to make an exception is possible, but only in very special circumstances.

To be able to make the choice from the topical potential that is most suitable to reach the desired result of the argumentation stage, the Supreme Court has prepared these choices in the opening stage. The Supreme Court chooses to present part C of the cassation grounds as a failing attempt to attack the decision by using the formulation that says that C ‘contests in vain’ part 5.18 of the argumentation. The Supreme Court presents the attacks in the cassation grounds A and B as failing attacks and characterizes them in legal terms as attacks that cannot lead to cassation ‘because of lack of interest’.

The concluding stage

Finally, in the concluding stage, the Supreme Court decides on the basis of this evaluation of the grounds of cassation in the argumentation stage that the appeal in cassation must be dismissed, which implies that the decision of the Court of Appeal can remain intact. The Supreme Court uses the space he has within his dialectical tasks and the authority he has on the basis of the applicable legal rules to present the choices he has made in the previous stages as a justification of his final decision.

The discussion strategy of the Supreme Court implies that it does two things at the same time. First it decides that the attacks by the plaintiff on the argumentation of the Court of Appeal have failed so that the decision can remain intact. Second, the Supreme Court gives an implicit interpretation of the argumentation of the Court of Appeal that departs from the way in which the argumentation was intended. This discussion move is not necessary to accomplish the dialectical goal of establishing the acceptability of the argumentation of the Court of Appeal because the Supreme Court can dismiss the appeal without this interpretation. The differing interpretation can be considered as an implicit ‘obiter dictum’ that the Supreme Court gives as a signal to the legal community in his capacity as judge of cassation to point out how the law should be developed. By choosing an interpretation in which the Supreme Court justifies the exception to article 1.100 clause 1 of the Civil Code on the basis of reasonableness and fairness that is supported by an appeal to the legal principles instead of a direct appeal to the legal principles, the Supreme Court makes indirectly clear that it does not want to consider the legal principles as the main argument and therefore as the main reason to make an exception.

3. Conclusion

With this analysis of the discussion strategy of the Supreme Court to establish the legal and argumentative function of certain legal principles in a concrete case as a systematic effort in the various discussion stages I have clarified how the Supreme Court combines a rational resolution of legal disputes and a rhetorical choice and presentation of discussion moves. The Supreme Court uses the space it has within the boundaries of his dialectical role and the applicable institutional rules to manoeuvre strategically to resolve the difference of opinion and at the same time establish the argumentative role of the applicable legal principles. In the opening stage the Supreme Court uses the space it has within the institutional boundaries to establish the common legal starting points. It establishes the content of the common legal starting points in such a way that it is able to give a negative evaluation of the attacks of the plaintiff in the argumentation stage. On the basis of this negative evaluation it can finally dismiss the appeal in the concluding stage. At the same time, the Supreme Court also uses the space it has within the institutional boundaries to establish the argumentative role of the common legal starting points. The Supreme Court decides that in making an exception to rule 1:100 of the law of inheritance, this exception must be restricted to the concrete case.

NOTES

[i] See the decisions published in NJ 1988/992, 8-4-1987, NJ 1989/369, 24-11-1988, NJ 1991/593, 7-12-1990.

[ii] Cf. the case of Riggs v. Palmer, 115 N.Y. 506, 22 N.E. 188 (1889) mentioned by Dworkin (1986, pp. 15-20) as an example of a systematic interpretation of the law of inheritance with the aim of clarifying the underlying principles.

[iii] For other analyses of the strategic manoeuvring in legal decisions see Feteris (2008, 2009a and 2009b).

[iv] In the case of legal justification the audience of the Dutch Supreme Court is a composite audience consisting of various ‘groups’. Firstly the audience consists of the parties in dispute. Secondly, in cases of appeal and cassation, the audience also consists of the judges that have taken prior decisions. Thirdly, the audience consists of members of the legal community of legal practitioners such as other judges and lawyers for whom the justification provides information about the way in which the law needs to be applied according to the Supreme Court. Although the decisions do not have the status of precedents, other judges and lawyers take into account the opinions of the Supreme Court in similar cases.

[v] See for a more extended analysis of the decision of the Supreme Court analysis D at the end of this contribution.

[vi] For the relevant parts of the decision of the Court of Appeal see E at the end of this contribution. For a more extended analysis of the argumentation of the Court of Appeal see B at the end of this contribution. For an analysis of the argumentation of the plaintiff see C at the end of this contribution)

[vii] See for the complete text of the justification of the Supreme Court F at the end of this contribution.

REFERENCES

Dworkin, R. (1986). Law’s empire. London: Fontana.

Eemeren, F.H. van (2010). Strategic manoeuvering in argumentative discourse. Extending the pragma-dialectical theory of argumentation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Eemeren, F.H. van, & Houtlosser, P. (2006). Strategic maneuvering: A synthetic recapitulation. Argumentation, 20, 4, p. 377-380.

Eemeren, F.H. van, & Houtlosser, P. (2007). Seizing the occasion: Parameters for analysing ways of strategic manoeuvring. In: F.H. van Eemeren, J.A. Blair, Ch.A. Willard & B. Garssen (eds.), Proceedings of the sixth conference of the International Society for the Study of Argumentation. Amsterdam: SicSat, p. 375-381.

Feteris, E.T. (2008). Strategic maneuvering with the intention of the legislator in the justification of judicial decisions’. Argumentation. Vol. 22, pp. 335-353.

Feteris, E.T. (2009a). ‘Strategic manoeuvring in the justification of judicial decisions’. In: F. H. van Eemeren (ed.), Examining argumentation in context. Fifteen studies on strategic manoeuvering. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, p. 93-114.

Feteris, E.T. (2009b) ‘Strategic manoeuvring with linguistic arguments in the justification of legal decisions’. Proceedings of the Second Conference Rhetoric in Society, Leiden University, 22-23 January 2009. (cd-rom).

Appendix

A. Legal rules applied in the case of the Unworty Spouse

Article 1:100 of the Old Dutch Civil Code

1. The spouses have an equal share in this divided community of property, unless a different division is established by means of a marriage settlement (…).

Article 4.3 of the New Dutch Civil Code

1.Legally unworthy to profit from an inheritance are: He who has been condemned irrevocably because he has killed the deceased, he who has tried to kill the deceased or he who has prepared to kill the deceased or has participated in preparing to kill the deceased.

Article 6:248, 2 of the Dutch Civil Code

An arrangement that is valid between the creditor and the debtor on the basis of the law, a custom or a legal act, does not apply if this is unacceptable from the perspective of the standards of reasonableness and fairness

Article 3:12 of the Dutch Civil Code

When establishing what reasonableness and fairness require, generally accepted legal principles, legal convictions that are generally accepted in the Netherlands, and social and personal interests in a particular case, should be taken into account.

B. Decision of the Court of appeal

1. The claim of L, stating that he is entitled to his share in the marital community of property, must be dismissed

1.1 L. should not profit from the marital community of property (5.17, 5.18)

1.1.1 In the special circumstances of the concrete case an exception to the legal division on the basis of article 1:100 of the Dutch Civil Code is justified on the basis of the following two legal principles:

1.1.1.1a He, who deliberately causes the death of someone else, who has benefited favoured him, should not profit from this favour (5.13) (legal principle P1)

1.1.1.1a.1 Article 3:959 of the Dutch Civil Code and article 4:1725 sub 2e of the Dutch Civil Code (5.14)

1.1.1.1b One should not profit from the deliberately caused death of someone else (legal principle P2)

1.1.1.1b.1 Article 3:885 sub 1e of the Dutch Civil Code

1.1.2 In the concrete case an exception to the legal division of the marital community of property on the basis of article 1:100 of the Dutch Civil Code is justified on the basis of reasonableness and fairness as specified in article 6:2 section 2 of the New Dutch Civil Code

1.1.2.1a The exceptional circumstances of the concrete case

1.1.2.1b He, who deliberately causes the death of someone else, who has favoured him, should not profit from this favour (5.13) (legal principle P1)

1.1.2.1b.1 Article 3:959 of the Dutch Civil Code and section 4:1725 sub 2e of the Dutch Civil Code (5.14)

1.1.2.1c One should not profit from the deliberately caused death of someone else (legal principle P2)

1.1.2.1c.1 Article 3:885 sub 1e of the Dutch Civil Code

C. Argumentation of the plaintiff in cassation

1. The decision by the court in which it denies my claim that I am entitled to my share in the marital community of property must be nullified because the court has made mistakes in the application of the law

1.1a The court erroneously has based its decision on the two general legal principles P1 and P 2 (grounds of cassation A and B attacking argument 1.1.1)

1.1a.1a These principles do not exist

1.1a.1b These principles do not apply because I am not favoured by the marriage

1.1a.1b.1 The marital community op property is not a favour and I have not profited from the death of mrs. Van Wylick because I had already become the owner of half of the marital community on the basis of my marriage with her

1.1b On the basis of article 11 AB the judge is not allowed to make an exception to a clear legal rule on the basis of reasonableness and fairness (ground of cassation C attacking argument 1.1.2)

D. Decision of the Supreme Court

1 The claim of L, stating that he is entitled to his share the marital community of property, must be dismissed

1.1.1 In the concrete case an exception to the legal division of the marital community of property on the basis of article 1:100 of the Dutch Civil Code is justified on the basis of reasonableness and fairness as specified in clause 6:2 section 2 of the New Dutch Civil Code

1.1.1.1a The exceptional circumstances of the concrete case

1.1.1.1b In the concrete case an exception to the legal division on the basis of article 1:100 of the Dutch Civil Code is justified on the basis of the following two legal principles:

1.1.1.1b.1a He, who deliberately causes the death of someone else, who has favoured him, should not profit from this favour (5.13) (legal principle P1)

1.1.1.1b.1a.1 Article 3:959 of the Dutch Civil Code and article 4:1725 sub 2e of the Dutch Civil Code (5.14)

1.1.1.1b.1b One should not profit from the deliberately caused death of someone else (legal principle P2)

1.1.1.1b.1b.1 Article 3:885 sub 1e of the Dutch Civil Code

E. Text of the decision of the court of appeal NJ 1989/369, 24-11-1988

5.13 Since the district court has assumed that Mrs. Van Wylick intended with the marriage – that also according to L was a marriage of convenience- a financial benefit for L, the district court has rightly stressed that to the factual situation described in the foregoing the general legal principle is applicable that he, who has deliberately caused the death of someone else, who has favoured him, should not profit from the this favour.

(…)

5.16 In this context it is also important to mention that the aforementioned legal principle is closely related to another legal principle, i.e. that one should not profit form the deliberately caused death of someone else, which principle has among others been expressed in article 885 under 1 book 3 CC.

(…)

5.17 Application of the mentioned legal principles leads under the aforementioned facts and circumstances to the conclusion that L is not entitled to the benefit that is the consequence of the community of property created by the marriage without a marriage settlement (‘huwelijkse voorwaarden’) with mrs. van Wylick.

5.18 Also an examination of the claims of L in light of the requirements of reasonableness and fairness according to which he is supposed to behave in the community of property that is created by the marriage, as is stated by Brouwers c.s., leads to the conclusion that L should not profit from the marital community of property. In this case the court applies a strict standard because the appeal to reasonableness and fairness is aimed at preventing the claims of L completely. Also when applying such a strict standard the court is of the opinion that the claims of L must be considered as so unreasonable and unfair, in the aforementioned special circumstances of this case and also considered in light of the mentioned general legal principles, that the exertion of the claimed rights must be denied to him completely.

F. Text of the decision of the supreme court NJ 1991/593 07-12-1990

Supreme Court:

(…)

3. Evaluation of the means of cassation

3.1.1 In cassation the following must be taken as a starting point:

L who is born in 1944, has taken care of the 72-year old van Wylick from January 1983 receiving payment in compensation for the care, initially several days per week and in a later stage on a daily basis. On September 29, 1983 L has married mrs. Van Wylick without making a marriage settlement. The marriage took place in another place than where the future spouses lived and no publicity was given to the marriage.

L owned practically nothing while mrs. Van Wylick brought in a considerable fortune. Both knew that the marriage would cause a considerable shift of property.

Since 1976 L had a relation with another man, which relation has not been broken.

Five weeks after the marriage L has killed van Wylick in a sophisticated way and with a gross breach of the trust that had been put in him. L has been condemned to a long term imprisonment for murder.

3.1.2 Furthermore, on the basis of these circumstances, in particular the short time between the marriage and the murder of mrs. Van Wylick, in the absence of any offer of proof to the contrary, the court has taken as a starting point that the sole reason for L to marry mrs. van Wylick was that he intended to appropriate her property and that already during the wedding, and in any case almost immediately after, L had the intention to kill mrs. van Wylick if she would not die in a natural way.

3.1.3 The court of appeal has, in a similar way as the district court, ruled that the question whether L has a right to half of the property belonging to the community property in the context of the partitioning and division of the community property, as far as this is brought in by mrs. van Wylick, must be answered negatively. This decision is contested by the means of cassation.

3.2 In the legal consideration 5.10 the Court of Appeal has taken as a starting point in answering the aforementioned question that in the light of the ‘exceptional circumstances of this case’ on the one hand consideration must be given to the general legal principles and on the other hand to the requirements of reasonableness and fairness according to which L is supposed to behave in the community property.

Furthermore the court has stated in legal consideration 5.13-5.17 that in this case two general legal principles apply and that on the basis of these principles L is not entitled to the benefits that originate from the community property. Against these two considerations the parts A and B of the means of cassation are aimed in vain.

As far as these parts are based on the statement that the general legal principles formulated by the court do not exist at all, this statement, that has not been substantiated, must be rejected as incorrect.

As far as these parts A and B are intended as an argument in support of the statement that these legal principles do not apply in a case as the case at hand because, briefly stated, the nature of the acquisition resulting from the community of property impedes that this acquisition can be considered as something that is equal to a ‘favour’ or an ‘ advantage’ as mentioned in these principles, they cannot lead to cassation because of a lack of interest. For the decision of the court is supported by the independent judgement formulated in consideration 5.18 that is, as will be explained below, contested in vain.

3.3 In legal consideration 5.18 the court has ruled that in the exceptional circumstances of this case ‘and also considered in light of the mentioned general legal principles’ the claims of L are so unreasonable and unfair that he must be denied the exertion of these rights completely. As appears from the cited formulation, in this context the legal principles play only the role that they have contributed to the decision of the court that the requirements of reasonableness and fairness make the exertion of the right to his share in the inheritance inadmissible. As far as the parts A and B read in legal consideration 5.18 that the court has used these principles as a direct legal ground for denying this right, they lack a factual basis. As far as they express the complaint that those principles cannot contribute to the decision of the court, they depart from a wrong conception of the law.

Part C attacks legal consideration 5.18 with the statement that the judge is not allowed to make an exception to 1:100, 1 of the Civil Code on the basis of reasonableness and fairness. This statement is wrong in its generality. For an exception is not completely excluded. The court has correctly stated that such an exception can only be made in very special circumstances, where the court speaks of ’ a very strict standard’ . In the circumstances that the court has taken as a starting point, the court has correctly decided that the unimpaired application of the equal division of the community of property based on the rule of article 1:100 clause 1 of the Civil Code between spouses in a dissolved matrimonial community, would, in the wording of article 6:2 clause 2 of the new Civil Code , be unacceptable according to standards of reasonableness and fairness.

On this ground the court has concluded that in the division of this community L is not entitled to the share in the community of property that has been brought in by van Wylick.

(…)

3.5 Since, as has been stated above, none of the parts succeed (‘treffen doel’), the appeal in cassation must be dismissed.

4. Decision

The Supreme Court:

dismisses the appeal;