ISSA Proceedings 2014 ~ Argumentative Strategies In Adolescents’ School Writing. One Aspect Of The Evaluation Of Students’ Written Argumentative Competence.

Abstract: Argumentation strategies constitute a crucial aspect of argumentation. The purpose of this paper is to explore the relations of the argumentative strategies observed in the writing of adolescents’ texts within language evaluation tests, to the elaboration of their theses and the evaluation of their argumentative competence. Despite the diversity of argumentative strategies employed, their standpoints are not fully elaborated and so their argumentative competence is diminished. These findings are important for the designing of argumentative teaching.

Abstract: Argumentation strategies constitute a crucial aspect of argumentation. The purpose of this paper is to explore the relations of the argumentative strategies observed in the writing of adolescents’ texts within language evaluation tests, to the elaboration of their theses and the evaluation of their argumentative competence. Despite the diversity of argumentative strategies employed, their standpoints are not fully elaborated and so their argumentative competence is diminished. These findings are important for the designing of argumentative teaching.

Keywords: Adolescents’ argumentation, argumentative competence, argumentative strategies, language evaluation.

1. Introduction

Argumentation strategies are of significant importance to the study and theory of argumentation. They reveal the deep structure of argumentation, the dynamic and convergent steps, moves and choices towards its construction, transcending semantic, pragmatic, lexico-grammar and rhetorical levels and relations. Strategic maneuvering is a term coined by pragma-dialectics to describe the multilayered functions of contextualized argumentation strategies (van Eemeren, 2010).

In evaluating students’ written argumentative competence, employment of a variety of strategies is considered a fundamental aspect of argumentation development (Swain & Suzuki, 2009). Argumentation strategies are connected to a high metacognitive level of awareness (Kuhn & Udell, 2007) revealing the abstract design patterns with and through which an argument text is constructed.

Within language evaluation tests, integration of reading and writing tasks draws a nexus of emerging dialectical argumentation strategies which supports students’ written argumentation potential. Nonetheless, activation of strategic routes to argumentation does not imply argument competence. It constitutes rather a first, step towards argumentative competence if reflective coordination, elaboration and contextualization of argumentative strategies do not apply.

1.1 Argumentation in educational context

Although arguing is considered an experiential ability acquired quite early in a child’s everyday life (Kuhn & Udell, 2003), its development and moreover its elaboration and connection to educational, institutional frames and disciplines is considered to be a highly demanding and challenging issue for both educators and students. Since critical thinking, science, communication, negotiation skills, decision making and social success were connected to argumentative skills (Baker, 2003, 2009; Byrnes, 1998; Gilardoni, pp. 723-725; Klaczynski, 2004; Kuhn & Udell, 2007, p. 90, Muller Mirza & Perret Clermont, 2009, pp. 127-144), teaching argumentation became a crucial issue for education. What is learned intuitively can be further elaborated through education thus offering equal opportunities for social and individual development to all social agents.

There have been various researches on the dynamics of argumentative skills within educational frames, all concluding its connection to a high metacognitive level, developed by age and institutional elaboration (Kuhn & Udell, 2003). Additionally, even teaching practice is regarded as a demanding argumentation approach (Macagno & Konstantinidou, 2012, pp. 2-3; Riggoti, 2007; Sandoval & Millwood 2005; Schwarz, 2009, pp. 91, 93).

1.2 Written argumentation in language education

Argumentation, as every communicational practice, is contextualized. Within pragma-dialectics this is a fundamental aspect of all the four principals (externalization, socialization, functionalization, and dialectification) in examining argumentation (van Eemeren, Grootendorst & Henkemans et al, 1996). Life domain, institution, instructional restrictions, subjects and culture construct the argumentative activity and consequently the argumentative type in practice (Eemeren van & Houtlosser, 2005, p. 70).

Although these variables are obvious in life situations and in dialogue involving agents’ interaction face to face, they are ‘hidden’ and require a cognitively demanding and conscious reconstruction in written argumentation, especially for a child, (Dolz, 1996; Rapanto, Garcia-Mila & Gilabert, 2013; Schwarz, 2009, p. 95) acquired through educational practices.

In language education students are asked to constantly move back and forth across a continuum consisting of two domain circles, the one of the physically observable context of education and the other of the life domain where the language learning activity is reflected. These moves are even more cognitively and communicatively demanding and require metacognitive awareness and strategic coordination, especially when the educational subject is written argumentation.

1.3 Language evaluation test, an educational context of emerging argumentation

One crucial and explicitly institutional oriented aspect of language education is language evaluation tests. Language evaluation tests comprise a special and crucial educational context, a special genre within the institutional learning domain of education. They are crucial in determining the degree to which accomplishment of learning goals is achieved by both educators and students and special in that they consist broadly a communicative and educational learning activity aiming not only to the educational context but to real life communicative competence. In defining argumentative activities as:

conventional entities that can be distinguished by ‘external’ empirical observations of the communicative practices in the various domains, or spheres of discourse, institutionally variants, some of which are culturally established forms of communication with a more or less fixed format (van Eemeren & Houtlosser, 2005, p. 76)

Van Eemeren and Houtlosser offer a descriptive tool for language evaluation tests as argumentative activities trying to convey ways to reasonably convince educators for students’ communicational skills within the restrictions posed by educational institutional frames while at the same time reflecting life communicative skills. This is especially obvious when the language assignment task in language evaluation tests concerns written argumentation.

In language evaluation tests, the integration of reading and writing tasks consists a textual and subjects’ network within which students’ written argumentation is constructed as an externalized, functional, social and dialogical communicative activity aiming to reasonably convince two interlocutors, the teacher, the physical subject of the educational context and the recipients of the text as these are constructed by the language assignment task. At the same time students’ are in dialogue, explicit or implicit, with the author of the text assigned for reading. Although reading and writing assignments are not always explicitly related in language evaluation tests, they consist interconnected, fundamental parts of literacy in educational contexts (Fitzgerald & Shanahan, 2000) creating thus an emerging dialogical context for language learning (Hyland, 2002, pp. 8-9; Nystrand, Camoran, Kachur & Prendergast, 1997) which comprises with the requirements of authenticity in language education (Hawkey, 2004b; Weigle, 2002; Weir, 2005b) and in argumentation in particular. This is especially obvious when there is a common thematic and generic textual orientation (Lemke, 1996, p. 259).

Effectiveness in language evaluation assignments is mainly considered towards three directions:

a. moving dynamically across a communicative continuum constructed by the language assignment task and the educational context,

b. understanding of discourse goals and

c. application of effective strategies to meet these goals.

The last two directions are recognized by Kuhn and Udell (2007) as being the two potential forms of development in argumentative discourse skills (Kuhn & Udell, 2007, p. 1246).

In learning and practicing written argumentation students have to strategically maneuver across, back and forth the communicational continuum constructed on the one hand by the language assignment task and on the other by the educational context, reconstructing a silent and physically absent dialogue as well as writtenly projected agents in the audience addressed (Hyland, 2002, p. 9).

The integration of reading and writing tasks in language evaluation tasks creates the prerequisite dialogical network for the emerging of critical exchanges and strategic maneuvering moves towards the construction of students’ argumentative text. Texts assigned for reading and writing form an intertextual network which activates students’ intertextual dynamics (Eco, 1979, p. 21) enriching their argumentative knowledge and competence by developing their ability to enhance a variety of argumentative moves within a dialogically rich textual frame echoing various voices and agents (Dimasi & Sachinidou, 2015; Panagiotidou, 2012). In that way, they form a ‘real life’ communicative setting (Hyland, 2002, p. 9).

1.4 Emerging argumentative strategies within language evaluation tests

According to Reisigl and Wodak strategy is “a plan of accurate practices more or less intentional including discursive practices to achieve a particular goal” (Reisigl &Wodak, 2001, p. 23; Reisigl &Wodak, 2009).

The recurrence and coordination of argumentative moves are considered as forms of argumentative strategies, strategic maneuvers (van Eemeren & Houtlosser, 2009, p. 7; Rocci, 2009, p. 258). In trying to construct their argumentative text, students use a variety of discourse strategies (Ferretti, Lewis, & Andrews-Weckerly, 2009; Nussbaum & Edwards, 2011) many of them emerging through the textual network constructed by the integration of reading and writing tasks in language evaluation tests. Language evaluation tests consists a hidden agenda of the constraints allowed and the opportunities offered by the educational context and the language curriculum in particular. The parameters determining the argumentative strategies used are also closely linked to the language assignment task and the communicative context designed by it.

Since argumentative strategies are communicatively contextualized, they are determined by the communicative objectives (Hyland, 2002, p. 35) designed by both the language assignment task and the language evaluation test. Rhetorical goal relating to genre and text type and informational goals such as subject matter as well as logical construction relating to the potential of argumentation schemes, direct the use of argumentative strategies. In a complimentary and more detailed approach, pragma-dialectics distinguishes the parameters of the strategic functions of argumentative maneuvers in:

a. results,

b. routes to achieve results,

c. constraints imposed by the institutional context and

d. commitments defining the argumentative situation (van Eemeren & Houtlosser, 2009, p. 11). Adaptation to the demands of the audience to which argumentation is directed, selection from the topical potential of argumentation and choice of the stylistic devices in the presentation of argumentation are also considered as aspects of strategic maneuvering (van Eemeren & Houtlosser, 1999, pp. 484-486; van Eemeren, 2010, Ch4) giving a more detailed account of the forms and choices argumentative strategic practices take.

The effectiveness of students’ written argumentation text is defined by subjects’ perceptions for argumentation formed within this communicational continuum between the educational context and the real life projection the later conveys. When looking into students’ argumentative strategies we can also gain insights into the educational formulation of their perceptions on what argumentation is and how it is effective, a reflection of the teaching and learning of argumentation.

2. Study

2.1 Research questions

a. What argumentative strategies do students employ within integrating reading and writing tasks in language evaluation tests while constructing their argumentative texts?

b. In what way do these strategies elaborate the validity of their standpoints and their argumentative competence?

2.2 Research material

2.2.1 Participants

Participants are twenty, 16 year old students, 9 females and 11 males, coming from an urban area and a low socioeconomic background, at the second, out of three, grade of the Greek Lyceum. The second grade of Lyceum schooling was preferred due to the proliferation of the language curriculum goals at that educational level and its connection to the learning and teaching of argumentation in particular. It is a grade just before the final grade of secondary schooling and students’ final exams to enter university, thus more directed to the secondary educational curriculum, without at the same time being strictly connected to the exams and related language evaluation tests for entering university.

The participants belong to the same class, randomly chosen out of five classes at the same Lyceum to promote a representative sample of an authentic class instance (Thomas, 2011), and were involved in the same language teaching course by the same teacher. In this way, they consist a relatively unified and at the same time authentic educational context for research (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

2.2.2 Data

The research material related to the final language evaluation paper given at the end of the school year 2013-2014, in a period of 2 hours, with integrating reading and writing assignments as designed by the Greek national language curriculum. Between texts assigned for reading and texts assigned for writing there are thematic and text type relevancies constructing an intertextual network, dynamically supportive for the writing of argumentative texts and thus of argumentative strategies involved. Institutional significance of final language evaluation tests is of importance since they compose one aspect of the degree to which language learning was accomplished and is numerically presented and valued by degrees of accomplishment.

The research focus was 20 argumentative texts written by students within the frame of their final language evaluation test as the main part of the assigned writing.

2.2.3 Methodology

Two school teachers, familiar with the language curriculum at Lyceum and argumentation theory, were chosen as independents raters of students’ texts. At first a ‘generous reading’ (Bartholomae, 1986; Donahue, 2008, p. 323) of texts and of the language evaluation test was conducted in order to acquire an overall and comprehensive perspective of the research material and to determine the levels, categories and units of research without pre acquired decisions on the research units that would impose a research perspective before ahead. Recurring patterns with similar textual functions at semantic, pragmatic, logic and lexico-grammar level were observed and categorized into research units.

The research units chosen, given the limitations of the current paper, are:

a. diversity of standpoints used,

b. gender diversity of standpoints,

c. elaboration of standpoints

e. idea negotiations with the reading assignment text

f. lexico-grammar construction of textual voice and communicational context g) argumentation schemes.

Each text was analyzed applying the units chosen. The consensus between the raters, expressed as the percentage of corresponding scores, is 87%.

2.3 Results

The language assignment task preceding the writing of students’ text, referred to a subject familiar to students by their language curriculum.

One of the most important problems of our time is the increase of unemployment, especially among young people. Investigate the reasons of the phenomenon as well as the consequences in the life of young people. Suppose that your text is the speech that you will give at an event that will be held at your school.’ (400-450 words).

The reading assignment text is an article in a daily newspaper written by a university teacher on the importance of higher education to social as well as individual life despite the growing numbers of unemployment for university degree holders.

2.3.1. Diversity of standpoints

The number of standpoints employed to meet the questions of the language assignment text concerning the reasons and consequences of young peoples’ unemployment are 68 for causes and 65 for consequences, a total of 133 standpoints, slightly privileging numerically standpoints for causes to standpoints for consequences in a percentage of 1,046%. Given the word limitations of the text (400-450 words), an average of 3,4 standpoints for reasons and 3,25 for consequences is considered a quite appropriate length for their further elaboration (Figure 1).

In 7 out of 20 texts the number of standpoints for reasons was equal to the number of standpoints for consequences. In 8 texts the difference between the standpoints for reasons and for consequences was only a minimum one, echoing teaching and curriculum directions of balance in the elaboration of the directions given by the language assignment task. In 5 texts, a difference of employment of reasons to consequences or vice versa is observed, revealing a difference in the knowledge dynamic for relevant information and ideas. More specifically, in 2 texts the standpoints employed for causes were 7 out 5 for consequences and 4 out of 1, whereas in 3 texts 4 standpoints were employed for causes out of 9 for consequences and relatively 1 out of 4 and 1 out of 3 (Figure 1).

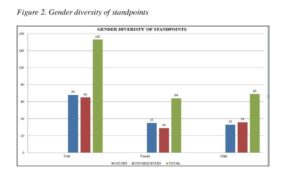

2.3.2 Gender diversity of standpoints

Gender diversity in number of standpoints deployed, although slightly favors males to females, falls under the statistical constraint that 55% of the participants are males and 45% females concluding to a female advantage of 2,17% standpoints. On the total, 69 standpoints were employed by males and 64 by females. Females employ more standpoints for reasons, 35 standpoints, while males 29, resulting to a 2,94% difference. Males employ 36 standpoints for consequences while females 29, a difference of 10, 77% (Figure 2).

2.3.3 Elaboration of standpoints

Elaboration of standpoints deployed is closely linked to the definition of argumentation as a composition of a structured constellation of propositions that mean to achieve its discursive purposes and reach a reasonable critique (van Eemeren & Grootendorst, 1992; van Eemeren et al, 1996, p. 5) and to its effectiveness and quality (De la Paz, Ferretti, Wissinger, Yee & Mac Arthur, 2012, p. 418; Ferreti et al, 2009; Nussbaum & Schraw, 2007; Walton, Reed & Macagno, 2008). In that sense, elaboration in argumentation transcends pragmatic, semantic, lexico-grammar and reasonable directions simultaneously. Hence, argumentative elaboration is also closely linked to argumentative structure, and argumentation schemes into their specific communicational context.

Argumentation structure comprises of explicitly, gradual and discursively interconnected propositions, structured constellations of students’ propositions aiming at the gradual elaboration of their standpoints (Garssen, 2001, p. 81; Shultz & Meuffels, 2011, p. 120; van Eemeren & Grootendorst, 2004, p. 4), relevant to the issue under discussion, with sufficient support to the main conclusion, and with reference to the logical acceptance of reasonable participants (Johnson & Blair, 1994, p. 55) and the communicational context. A successful argument is semantically, syntactically and pragmatically valid (Minghui Xiong & Yi Zhao, 2007, p. 3).

One aspect of argumentation structure is argumentation schemes which for Macagno (2015) represent the formalization of abstract patterns of argumentative inference combing “material links with logical relations between the premise and the conclusion in an argument” (Macagno, 2015, pp. 2-3), “an abstract frame that expresses the justificatory principle employed by the arguer”, as Hitchcock and Wagemans noted (Hitchcock & Wagemans, 2011, p. 185) “in order to promote a transfer of acceptability form the explicit premise to the standpoint” (van Eemeren & Grootendorst, 2004, p. 4). Argumentation schemes transcend the semantic and reasoned structure of argument and offer us a descriptive, reflective, analytical and evaluative insight to the structure of argumentation and argumentative text.

As a consequence, in defining whether a standpoint is elaborated the criteria proposed and applied in the present study are : a) reference to the issue under discussion, b) adequate advancement of links between premises and the standpoint one wishes to defend via argument schemes so as to insure acceptability of the premise and sufficiency of transference to the standpoint (Garssen, 2001, p. 81), c) argumentative discourse indicators d) appeal to audience reasonableness and e) communicational contextualization for the specific activity type or genre argumentation is aimed.

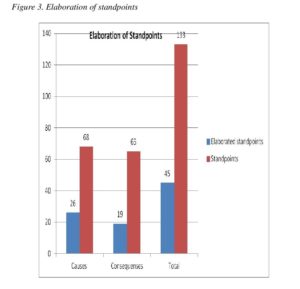

Only 35 standpoints out of 132 were elaborated by students, a percentage of 37, 7%. Elaboration of standpoints is mainly related to reasons, 26 out of a total of 68, a percentage of 38, 24% and 19 out of a total 64 for consequences, a percentage of 29, 23%. The 42 standpoints related to reasons and the 46 standpoints related to consequences consisted merely of one proposition leaving other premises and inference unexpressed and implicit. Females constructed 23 elaborated standpoints and males 24 which given the gender statistical difference of the participants, results to an almost equality (Figure 3).

2.3.4 Negotiations with the reading assignment text

At the semantic level of argumentation students negotiated and transformed ideas from the reading assignment text thus applying in writing the knowledge transforming model which is considered most appropriate for the writing of argumentation texts (Andrews, 1995, p. 167; Baker, 2009, p. 138; Grabe & Kaplan, 1996, pp. 121-2). With negotiation, reference is made to the deployment and interactional construction of meanings and to lexico-grammar and reasoned structures that subjects’ activate within communicational contexts in their effort to convey meanings and communicate, a strategy quite familiar to the integration of reading and writing tasks (Donahue, 2004; Garcia-Mila & Andersen, 2007, p. 42; Sachinidou & Dimasi, 2010). For the purpose of this paper, negotiation focused only to the semantic grounds of ideas and information between the reading and the writing assignment text.

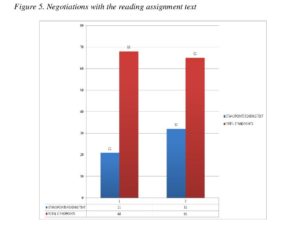

Negotiations were numbered according to ideas students used from the reading assignment text, to deploy standpoints. 21 one out of 68 (31%) standpoints for the causes of young peoples’ unemployment and 32 out 65 (49, 23%) standpoints for the consequences of unemployment are found in the reading assignment text. Students retrieve and transform ideas and information from the reading assignment text related to the subject and goal of their text and consequently diminishing the cognitive load that argumentation involves (Kuhn & Udell, 2007, p. 1247). Idea selection with reasoned discourse is an additive value to the construction and development of argumentation (Anderson, Chinn, Waggoner & Nguyen, 1998, p. 172). Semantic negotiations reveal a dialogical and intertextual dimension of students’ argumentation texts that enhances their effectiveness by invoking strategies supportive of argumentation (Figure 5).

2.3.5 Lexico-grammar construction of textual voice and communicational context

Textual voice and textual identity are defined both by the communicational and social potentials (Scollon, 1996, p. 7). In writing argumentative texts within the assignments of the language evaluation test, students engage in the construction of a textual voice as designed by both the language assignment task and the educational context comprised by the language evaluation test.

Lexico-grammar construction of textual voice reveals one aspect of style and stylization and the strategies involved in presenting different voices and selves in the discourse (De Fina, 2011, p. 273; Fahnestock, 2011, p. 279) employing and at the same time revealing genre constraints, opportunities and dynamics and subjects’ communicational potential and knowledge not only as discourse producers but as discourse recipients as well. The lexico-grammar construction of textual voice situates the writer and the reader in the communicational context as potentially interactional agents and constantly inscribes, changes and challenges their cognitive representations (Van Dijk, 1998, 2010) thus directing to argumentation (Rocci, 2009, p. 258).

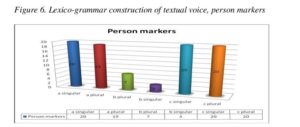

Person markers are one aspect of lexico-grammar construction of textual voice under various forms, mainly in the pronoun system and verb suffixes’.

The first singular person was used in all 20 texts. In 19 out of 20 texts first plural person was used. In 7 texts, second plural person was included and in just 3 texts appeared second singular person. In all texts third singular and third plural persons were used. Genre of language assignment, speech to an audience, contextualized students’ choices of person markers’. Emphasis was given to the first singular and first plural person and third singular and third plural person which were present in all texts.

Writer’s voice is explicitly stated and differentiated by other textual voices in the first singular person, discursively constructing an identity of a knowledgeable subject whose judgment is clearly fore grounded and appreciated for its expertise and authoritative power and thus increasing persuasive effects (Schulze, 2011, p. 132). First plural person, observed in 19 texts in an inclusive sense unities writer and reader (Fahnestock, 2011, p. 285) as belonging to the same identity group, with mutual perspectives and interests as designed by the language assignment task. Obvious audience appeal is observed in 7 texts with second plural person, “one of the markers of a more oral style” (Fahnestock, 2011, p. 281), in accordance with the public speech genre to which the language assignment task is directed. Second singular person was used only in three texts in the generic sense of a rhetorical appeal to the human audience. Third singular and third plural person were used in all 20 texts stating the objective positioning of an observer to actions, subjects, ideas, a premise of reasonableness (see figure 6).

2.3.6 Argumentation schemes

Argumentation schemes represent abstract patterns of semantic, pragmatic and reasonable relations between the premise and the conclusion in different and dynamic combinations (Macagno, 2015). The direction in which the activation of these combinations will be driven, is drawn in a map of complex possibilities and is closely related to the purpose of the argument and therefore to its pragmatic meaning emerged in a communicational context as well as to the strategies connected with the purpose of the move. The strategies available or of which a subject avails himself of, direct the combination of relations represented by argumentation schemes in the perspective of the ontological structure of the subject matter of the claim (Macagno, 2015, pp. 20-24).

In referring to the causes and consequences of young peoples’ unemployment, the language assignment task oriented students mainly to causal argumentation, structured on an interdependent chain of reasons and effects and thus facilitating and supporting two argumentative aspects of argumentation schemes:

a. promote transfer of acceptability from explicit premises to the standpoint and

b. fit to the sort of propositions (Garssen, 2001, p. 91) the assignment task is oriented to. Since the purpose is to support a judgment in a state of affairs, what causes young peoples’ unemployment and the consequences that this has on their lives, the writer had to choose how to structure his arguments following two directions:

a. external arguments based on speaker’s superior knowledge and

b. internal arguments providing reasons on the features and characteristics of the subject matter to support an evaluative judgment on an entity or a state of affairs (Macagno, 2015, p. 21).

In using the first singular verbal person and thus constructing a knowledgeable identity, students chose an external argument perspective. At the same time, providing reasons on the actions that lead to young peoples’ unemployment and the consequences that this has on them, they characterize and evaluate entities and activities “aligning the addressee into a community of shared values and hierarchies of values and beliefs” (Martin & Rose, 2005, p. 95) and thus using internal arguments. The view point of the language assignment task directed another aspect in students’ argumentative schemes. In arguing about the reasons of young peoples’ unemployment they evaluate mainly actions and activities while in arguing for the consequences of the subject matter they evaluate entities of being, ascribing attitudes to subjects’ behavior.

3. Conclusions

Before drawing on to the conclusions of the study it must be noted that it concerns a small group of students and can only be indicative for further future research.

A variety of argumentative strategies employed by students within integrating reading and writing tasks in language evaluation tests in constructing their argumentative texts is observed.

More specifically:

a. There is a variety and a significant number of standpoints deployed. 133 standpoints were indentified in 20 texts, an average of 6, 65% per text (figure 1). The increased number of standpoints is considered as a presupposition for a reader that needs to be convinced or is in need for more information (Martin & White, 2005, p. 119), a goal in accordance with argumentation development (Knapp & Watkins, 2005, p. 192) and educational contexts.

b. There is 2, 17% gender diversity on standpoints employed, slightly privileging females to males (figure 2).

c. Elaboration of standpoints is quite low, only 37,7%, 35 out of 133 standpoints employed. Students, both females and males, rest at the standpoint of the argument not making explicit premises aiming to conclusion justification and thus dispersing the relevance of the standpoint to its conclusion and the issue under discussion while minimizing the depth and effectiveness of argumentation (Knapp & Watkins, 2005, p. 192; De La Paz et al, 2012, p. 418) and its validity (van Eemeren, Grootendorst & Henkemans, 2002, p. 132) (figure 3).

d. The elaboration of their standpoints is mainly related to the causes of the issue under discussion (figure 3).

e. Students transform, modify and adjust the information of the text assigned for reading, to the goals of the new communicative circumstance, recontextualising and negotiating meanings and structures (Donahue, 2008, pp. 90-103; Linell, 1998, p. 154; Plakans & Gebril, 2012) and in this perspective, constructing a basic premise of argumentation (Baker, 2003, 2009) (figure 5). Despite this knowledge supporting negotiation moves, students lack elaboration of relatively standpoints constructed. Although they seem to direct themselves to a knowledge transforming writing model, they apply ultimately a knowledge telling model (Grabe & Kaplan, 1996, pp. 121-122; Bereiter & Scardamalia, 1987), making only a move related to the semantic transformation of the information with no further elaboration. This, according to Plakans and Gebril (2012), consists an indication of “possible need for firm teaching direction, especially if the task is persuasive writing” (Plakans & Gebril, 2012, p. 31).

f. In negotiating semantically with the reading assignment text, students deploy nomination and explicitly referential strategies drawing from a common pool of words from the text read and cultural strategies drawing from a common cultural pool of ideas (Lemke, 1992).

g. They take distances from the reading text at whatever they disagree with thus forming implicitly stated counterarguments which is considered as a differentiated characteristic of mature argumentative writing (Knapp & Watkins, 2005, p. 192; Kuhn, 2005).

h. They invoke experiential material in their effort to explicitly construct their arguments in lack of content knowledge (De La Paz et al, 2012, p. 417; Donovan & Bransford, 2005; Ferretti et al, 2009).

j. They discursively construct, using lexico-grammar devices such as person markers, an identity of a subject whose viewpoint and life perspective is argumentatively and institutionally valued.

k. Students’ schematic strategies are in response to their task assignment and the reading text.

l. Schematic strategies are explicitly, discursively and semantically stated with discourse markers (conjunctions, verbs, nouns).

The contextual framing of students’ strategies in a continuum between the physical observable educational context and the communicational context formed by the language assignment task comprises an important step towards their argumentative and communicational competence (van Eemeren & Houtlosser, 2005; van Eemeren, 2010).

Despite the variety of strategies used and their contextualization, students’ argumentation remains at the start point of their standpoints, merely listing information with little elaboration and coordination of the explicit reasoning and rhetorical steps leading to the conclusion of their arguments and the support of the issue for which they argue. In the argumentation strategies used, students reveal a primary and shallow knowledge of results, routes to achieve results, constraints imposed by the institutional context and commitments defining the argumentative situation (Igland, 2009, p. 510; van Eemeren & Garssen, 2008, p. 11). Their argumentative strategies are inconsistent, only applying patterns learned as steps for argumentation construction which often left implicit and with little elaboration to reach inferences. In that sense, their strategic maneuvering is incomplete and ineffective.

Systematic teaching and learning of contextualized argumentative moves as classes of dynamic, rich and open ended activations of choices building argumentative strategies and argument validity is needed. This does not mean that teaching and learning of argumentative moves should be seen as a canonical classification and employment of relative moves but rather as a strategic maneuvering of constantly reflecting, structuring and restructuring moves and involving into a variety of argumentation instances and activities in order to form a metacognitive and dynamic awareness of argumentation.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank Professor Maria Dimasi at Democritus University of Thrace, Greece, department of Language, Philology and Culture of Black Sea Countries, for directing her to argumentation studies and Professor Fabrizio Macagno at Universita Nova De Lisboa, Portugal, for trusting her with a copy of his article to be published.

References

Anderson, R. C., Chinn, C. A., Waggoner, M., & Nguyen, K. (1998). Intellectually stimulating story discussions. In J. O. Lehr (Ed.), Literacy for all (pp. 170-196). New York: Guilford.

Andrews, R. (1995). Teaching and learning argument. London: Cassell.

Baker, M. J. (2003). Computer-mediated argumenative interactions for the co-laboration of scientific notions. In J. Adriessen, M. J. Baker, & D. Suthers (Eds.), Arguing to learn: confronting cognitions in Computer-Supported collaborative Learning Enviroments (pp. 47-78). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Baker, M. J. (2009). Argumenative interaction and the social construction of knowledge. In N. Muller Mirza, & A.-N. Perret-Clermont (Eds.), Argumentation and Education: Theoritical Foundations and Practises (pp. 127-144). Berlin, Germany: Sringer-Verlang.

Bartholomae, D. (1986). Wanderings: misreadings, miswritings, misunderstandings. In T. Newkirk (Ed.), Only connect: Uniting reading and writing (pp. 89-118). Portsmouth, NH: Boynton-Cook.

Bereiter, C. & Scardamalia, M. (1987). The psychology of written composition. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Byrnes, J. P. (1998). The nature and development of decision making: a self-regulation model. Mahwah NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

De Fina, A. (2011 (2nd edition)). Discourse and identity. In T. V. Dijk (Ed.), Discourse Studies. A Multidisciplinary Introduction (pp. 263-282). London: Sage Publications.

De la Paz, S., Ferretti, R., Wissinger, D., Yee D.& Mac Arthur, C. (2012, October). Adolescents’disciplinary use of evidence, argumentative strategies, and organizational structure in writing about historical controversies. Written Communication, 29(4), 412-454.doi:10.1177/0741088312461591.

Dimasi, M & Sachinidou, P. (2015). The contextual intertextuality of reading and writing in secondary schooll (in greek). Proceedings of the 10th International Lunguistics Conference 24-29 September 2013, (to be published). Rhodes, Greece.

Dolz, J. (1996). Learning argumentative capacities. Argumentation, 10(2), 227-251.

Donahue, C. (2004). Student writing as negotiation: fundamental movements between the common and the specific in French essays. In F. Kostouli (Ed.), Writing in Context(s):Textual Practices and Learning Processes in Sociocultural Settings. Amsterdam: Kluwer Academic Publish.

Donahue, C. (2008). Cross-cultural analysis of student writing: beyond discourses of difference. Written Communication, 25(3), 319-352.

Donovan, M. S. & Bransford J. D. (2005). How students learn: mathematics in the classroom. Committee on how people learn: a targeted report for teachers, Board on Behavioral, Cognitive, and Sensory Sciences. National Research Council, Board on Behavioral, Cognitive, and Sensory Sciences, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washigton D.C.: The National Academies Press.

Eco, U. (1979). The role of the reader: explorations in the semiotics of texts. Indiana: Indiana University Press.

Eemeren F. H. van, Grootendorst R. & Henkemans S.F et al. (1996). Fundamentals of argumentation theory. A handbook of historical backgrounds and contemporary developments (1st ed.). Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlabaum Associates, Publishers.

Eemeren, F. H. (2010). Strategic maneuvering in argumentative discourse. Extending the pragma-dialectical theory of argumentation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Eemeren, F. H. van & Garssen, B. (2008). Controversy and confrontation in argumentative discourse. In F. H. van Eemeren, & B. Garssen (Eds.), Controversy and confrontation: relating controversy analysis with argumentation theory (pp. 1-26). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Eemeren, F. H. van & Houtlosser, P. (1999). Strategic maneuvering in argumentative discourse. Discourse, 1, 479-497.

Eemeren, F. H. van & Houtlosser, P. (2005). Theoretical construction and argumentative reality: an analytic model of critical discussion and conventionalised types of argumentative activities. In D. Hitchcock, & D. Farr (Eds.), The Uses of Argument. Proceedings of a Conference at Mc Masters University 18-21 May 2005 (pp. 75-85). Ontario: Ontario Society for the Study of Argumentation.

Eemeren, F. H. van & Houtlosser, P. (2009). Strategic maneuvering. In F. H. van Eemeren (Ed.), Examining Argumentation in Context: Fifteen studies on strategic maneuvering (pp. 1-24). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Eemeren, F.H. van & Grootendorst, R. (2004). A systematic theory of αrgumentation : the pragma-dialectical approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Eemeren, F.H. van, & Grootendorst, R. (1992). Argumentation, communication, and fallacies: a pragma-dialectical perspective. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Eemeren, F.H. van, Grootendorst, R. & Henkemans, F.S. (2002). Argumentation: analysis, evaluation, presentation. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Fahnestock, J. (2011). Rhetorical style: the uses of language in persuasion. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

Ferretti, R.P., Lewis, W.E, & Andrews-Weckerly, S. (2009). Do goals affect the structure of students’ argumentative writing strategies? Journal of Educational Psychology, 101(3), 577-589.

Fitzgerald, J., & Shanahan, T. (2000). Reading and writing relations and their development. Educational Phycologist, 35, 39-51.

Garcia-Mila, M. & Andersen, C. (2007). Cognitive foundations of learning argumentation. In S. Erduran, & M. P. Jimenez-Aleixandre (Eds.), Argumentation in science education. Perspectives from classroom research. Science and Technology Library (Vol. 35, pp. 29-45). Amsterdam, Netherlands: Springer.

Garssen, B. J. (2001). Argument schemes. In F. H. van Eemeren (Ed.), Crucial concepts in argumentation theory (pp. 81-99). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Gilardoni, S. (2009). Argumentation in classroom interaction. Teaching and learning Italian as a second language. In G. Gobber, S. Cantarini, S. Cigada, M. C. Gatti, & S. Gilardoni (Eds.), Proceedings of the IADA workshop, Word Meaning in Argumentation Dialogue, 15-17 May 2008. Special Issue. 2, (pp. 723-737). Milan: Facolta di Scienze Linguistiche et Letterature Straniere, Universita Catholica del Sacro Cuore.

Grabe, W. & Kaplan, R. B. (1996). Theory and practice of writing: an applied linguistic perspective (Applied Linguistics and Language Study). London: Routledge.

Hawkey, R. (2004 b). A modular approach to testing English language skills. The development of the Certificates in English Language Skills (CLES) examinations. Studies in language testing (Vol. 16). (M. Millanovic, & C. Weir, Eds.) Cambridge: Cambridge Universtiy Press.

Hitchcock, D. & Wagemans, J . (2011). The pragma-dialectical account of argumentation schemes. In E. Feteris, B. Garssen, & F. Snoeck Henkemans (Eds.), Keeping in Touch with Pragma-Dialectics: In honor of F. H. van Eemeren (pp. 185-205). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Hyland, K. (2002). Teaching and researching writing. London: Longman.

Igland, M.-A. (2009). Negotiating problems of written argumentation. Argumentation, 23, 495-511.

Johnson, R. H. & Blair, A. (1994). Logical self-defense (U.S. edition). New York: McGraw Hill.

Klaczynski, P. A. (2004). A dual-process model of adolescent development: implications for decision making, reasoning, and identity. In R. V. Kail (Ed.), Advances in child development and behavior (Vol. 32, pp. 73-119). San Diego, CA: Elsevier Academic Press.

Knapp, P. & Watkins, M. (2005). Genre, text, grammar: technologies for teaching and assessing of writing. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press.

Kuhn D. & Udel W. (2003). The development of argument skills. Educational Pchycologist, 74(5), 1245-1260.

Kuhn, D. (2005). Education for thinking. USA: Harvard University Press.

Kuhn, D. & Udell, W. (2007). Coordinating own and other perspectives in argument. Thinking and Reasoning, 13(2), 90 – 104.

Lemke. (1992). Intertextuality and educational research. Linguistics and Education, 4(3), 257-267.

Lincoln, Y.S. & Guba, E.G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Linell, P. (1998). Discourse across boundaries : on recontextualizations and the blending of voices in professional discourse. Text, 18(2), 143-157.

Macagno, F. (to be published 2015). Classifying the patterns of natural arguments. Philosophy and Rhetoric.

Macagno, F.& Konstantinidou, A. (2012, November 11). What students’ arguments can tell us: using argumentation schemes in science education. Retrieved from SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2185945 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2185945.

Martin, J.R. & White P.R.R. (2005). The language of evaluation. Appraisal in English. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Minghui Xiong & Yi Zhao. (2007). A defeasible pragma-dialectical model of argumentation. Proceedings of the sixth Conference of the International Society for the Study of Argumentation (pp. 1541-1548). Amsterdam: Sic Sat.

Muller Mirza N.& Perret Clermont, A. (2009). Argumentation and education: theoritical foundations and practises. Berlin: Springer.

Nussbaum, M. E. & Edwards, O. V. (2011). Critical questions and argument stratagems: a framework for enhancing and analyzing students’ reasoning practices. Journal of the Learnning Science, 20(3), 443-488.

Nussbaum, M.E. & Schraw, G. (2007). Promoting argument–counterargument integration in students’ writing. Journal of Experimental Education, 76(1), 59-92.

Nystrand, M.& Camoran, A.& Kachur, R.& Prendergast, C. (1997). Opening dialogue: Understanding the dynamics of language and learning in the english classroom. New York: Teachers’ College, Columbia University.

Pangiotidou, M. E. (2011). Cognitive approach to intertextuality: the case of semantic intertextual frames. Newcastle Working Papers in Linguistics. 17, 173-187. Newcastle: University of Newcastle.

Plakans, L.M & Gebril, A. (2012). A close investigation into source use in integrated second language writing tasks. Assessing writing, 17(1), 18-34.

Rapanto, C., Garcia-Mila, M.& Gilabert, S. (2013, May). What is meant by argumentative competence? An integrative review of methods of analysis and assessment in education. Review Of Educational Research, 83(4), 483-520. doi: 10.3102/0034654313487606.

Reisigl, M. & Wodak R. (2001). Discourse and discrimination: rhetorics of racism and antisemitism. London: Routledge.

Reisigl, M., & Wodak, R. (2009, 2nd revised edition). The discourse-historical approach (DHA). In R. Wodak, & M. Meyer (Eds.), Methods for Critical Discourse Analysis (pp. 87-121). London: Sage.

Rigotti, E. (2007, 12). Introdurre alla realta attraverso e discipline. I quadermi di Liberta di educazione, 67-70.

Rocci, A. (2009). Maneuvering with voices. The polyphonic framing of arguments in an institutional advertisement. In F. H. van Eemeren (Ed.), Examinig Argumentation in Context: Fifteen studies on strategic maneuvering (pp. 257-284). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Sachinidou, P. & Dimasi, M. (2010). Texts’ and writters’ dialogues. Texts as expressions of discourse negotiations constructing subject’s identity (in greek). In K. Dimadis (Ed.), Proceedings of the 4th Congress of the European Society of Modern Greek Studies. 9-12 September, Granada. (1, pp. 119-138). Granada, Spain: hhtpp//www. eens.org.

Sandoval, W. & Millwood, K. (2005). The quality of students’ use of evidence in written scientific explanations. Cognition and Instruction , 23(1), 23-55.

Schulz, P.J. & Meuffels, B. (2011). Breast cancer screening. A case point. In E. Feteris, B. Garssen, & F. Henkemans (Eds.), Keeping in touch with pragma-dialectics: In honor of F.H. van Eemeren (pp. 117-133). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Schulze. (2011). Writing to persuade: a Systemic Functional Linguistic view. Gist Education and Learning Research Journal, 3, 127-157.

Schwarz, B. (2009). Argumentation and learning. In N. Muller Mirza, & A.-N. Perret Clermont (Eds.), Argumentation and Education.Theoritical Foundations and Practices (pp. 91–126). Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag. Retrieved from doi:10.1007/978-0-387-98125-3_4

Scollon, R. (1996). Discourse identity, social identity, and confusion. Intercultural Communication Studies, 6(1), 1-16.

Swain, M. & Suzuki, W. (2009). Interaction, output, and communicative language learning. In B. Spolsky, & F. Hult (Eds.), The handbook of educational linguistics (pp. 557–570). Malden, MA: Willey-Blackwell Publishing.

Thomas, G. (2011). A typology for the case study in social science following a review of definition, discourse, and structure. Qualitatuve inquiry, 17(6), 511-521.

Van Dijk, T. (1998). Ideology: a multidisciplinary approach. London: Sage Publications.

Van Dijk, T. (2010). Political identities in parliamentary debates. In C. Ilie (Ed.), European Parliament under scrutiny. Discourse strategies and interaction practises (pp. 29-56). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Walton, D., Reed, C., & Macagno, F. (2008). Argumentation schemes. Cambridge England: Cambridge University Press.

Weigle, S. (2002). Assessing writing. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Weir, C. J. (2005b). Language testing and validation:an evidence-based approach. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave.