ISSA Proceedings 2014 ~ The Evaluative And Unifying Function Of Emotions Emerging In Argumentation: Interactional And Inferential Analysis In Highly Specialized Medical Consultations Concerning The Disclosure Of A Bad News

No comments yetAbstract: This paper investigates the functions of emotions in decision-making processes following the disclosure of a bad news in medical argumentation, by taking into account suggestions from psychology and argumentation. I embrace the hypothesis that emotions, due to their capability of unifying the objects of our thought, strongly contribute to reasonable decisions. I claim that a proof that hints to this can be found at the interactional as well as at the inferential level of analysis.

Keywords: Argumentum Model of Topics, bad news, decision-making processes, doctor-patient interaction, emotions, inferential structure, interactional analysis

1. Introduction

Emotions plays a crucial role in doctor-patient interactions, especially in case of bad news’ disclosure; in such highly emotive frameworks a competent usage of emotions through communication strategies can really make the difference in improving patients’ acceptability of heavy treatments and of diseases’ consequences. This competence is often strongly influenced by doctors’ ability to handle in an adequate way their own emotions as well as by the ability to take into account patients’ possible emotive reactions. However, it is not often the case that doctors are able to reach a fruitful communication and an adequate handling of emotions, and this leads to misunderstandings and produces undesired emotive and cognitive reactions in patients. Two are the main approaches to doctor-patient interaction which can be found in literature, namely the patient-centred approach and the disease-centred approach (Bensing, 2000; Mead & Bower, 2000).

This paper aims to contribute to the study of doctor-patient interactions’ dynamics by connecting existing studies in health communication and psychology with argumentation studies, in order to demonstrate the crucial role of argumentatively played out emotions. For what concerns the theoretical and methodological framework, we follow the Pragma-Dialectical approach (Eemeren van, 2004) for the interactional analysis and the Argumentum Model of Topics (henceforth AMT) for the analysis of the inferential structures of arguments (Rigotti, 2009; Rigotti & Greco Morasso, 2010).

In medical argumentation studies there is a gap in the analysis of doctors’ argumentatively played out emotions, which concerns both the interactional as well as the inferential level of analysis. The reasons why doctors’ emotions emerging in argumentation during this type of communicative practice have a strong influence in patients’ acceptability of treatments and of disease consequences remain still unclear.

In this study I propose to combine a fine-grained argumentative and inferential analysis of doctors’ experienced emotions in doctor-patient interactions concerning the disclosure of a bad news. Three are the main aims of this paper. Firstly, I set out to explore the role of doctors’ argumentatively played out emotions in the management of the painful communication and of the subsequent patients’ decision-making processes. Secondly, I will investigate the importance for doctors to take into consideration the possible patients’ emotions and the importance of arguing in favor of them, and lastly I will prove that emotions have an evaluative and unifying function which can be retrieved in the inferential structure of arguments.

2. Two distinct approaches to doctor-patient interaction

First of all, the disease-centered approach reduces the relationship doctor-patient to a mere formality lacking of a human and existential value, which is on the basis of every cure strategy. It conceives the doctor as the only expert and the doctor’s only focus is on the disease in itself, so that all his professional efforts and human attentions are devoted only to the cure of the disease. As a consequence of that, the patient is induced to adopt a behavior of compliance, that consists in obeying and adhering to doctors’ decisions, preventing him from reaching an autonomous opinion (RPSGB, 1997).

On the contrary, the patient-centered approach puts the patient as a whole at the center of its interest; the doctor gives crucial importance to psychological and social conditions of the patient, taking into consideration patients’ emotive dynamics and considering the consequences of emotive reactions in decision-making processes, in order to be able to better understand the actual will of the patient and subsequently to be able to better guide him in painful decisions. This is possible only caring about communicative and relational aspects between doctor and patient; adopting such an approach instead of a disease-centered approach implies a shift of focus from the cure of the disease to the care of the person, and from the compliance to the concordance, which refers to a process of knowledge power and decision sharing in doctor-patient interaction, producing a radical change of the cure’s intrinsic relationship and of what every participant expects from the other. In short, adopting a patient-centered approach favoring concordance means considering the patient as an expert of his own illness situation and of his reaction to bad news communication and treatment (RPSGB, 1997).

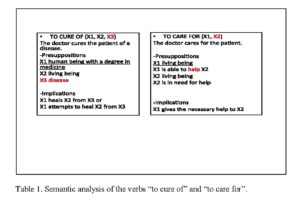

For the purposes of this study, which combines studies from communication, psychology and argumentation theory, it is interesting to notice the semantic foundations of the distinction of these two approaches; indeed, also a semantic analysis of the two verbs to cure of and to care for, respectively representing the disease-centered approach and the patient-centered approach, lays stress on the different perspective given to the medical communication by the adoption of these two types of approaches. In order to highlight this distinction, I analyzed these verbs following an approach known as Congruity Theory (Rigotti & Rocci, 2001; Rocci, 2005). This theory starts from the assumption that a whole argumentation is based on a conceptual structure, proceeding from relations to concepts, and therefore the analysis of argumentation presupposes the analysis of concepts, that is the semantic analysis. In short, this theory provides the necessary and conceptual instruments necessary to tackle both the semantic and the pragmatic aspect of discourse. More specifically, the meaningfulness of the units that make up the nodes of discourses is accounted for semantically in terms of predicate-argument frames, where predicates impose presuppositions to their arguments places and licenses semantic entailments. The semantic analysis of the two verbs to cure of and to care for is shown in Table 1.

The verb to cure of presupposes that X1 is a human being with a degree in medicine, that X2 is a living being and that X3 is a disease. The subsequent entailments are that X1 heals X2 from X3 or that X1 attempts to heal X2 from X3. Here the verb is clearly bound to the concept of disease, where the focus is on the disease per se. On the contrary, the verb to care for presupposes as first argument a living being, that is able to help X2, and furthermore it presupposes that is X2 is a living being, who is in need for help, where the entailment is that X1 gives the necessary help to X2. This verb perspective is related to the concept of illness, and here the focus is on the fact of being ill of a person in his whole and uniqueness.

3. Emotions emerging in argumentative doctor-patient interactions

It is in this scenario that I propose to consider emotions emerging in argumentative doctor-patient interactions as able to strongly influence the modality of communicative approach adopted, and strongly determine an adequate or inadequate management of the painful disclosure of a bad news, such as the communication of the impossibility to surgically intervene in pancreatic cancer (for more details see the case study in Section 5).

I will refer to emotions as they are conceived according to the modern theories of emotions in social psychology and psychology of emotions; the central core of these theoretical frameworks is based on the assumption that emotions are rational, so that they are conceived as a useful mean to reach reasonable decisions, as stated also by the neuroscientist A. Damasio (Damasio, 1994; Damasio, 1999).

However, it is only when one is aware of his own emotions that can inhibit an action prompted by them (Lambie, 2008; Lambie 2009). I embrace this hypothesis that in order to make a reasonable choice, one should be aware of his own emotions. Nevertheless, one step further still needs to be done; I claim that emotions’ awareness is strongly played out argumentatively. Furthermore, in support of this claim, I take into consideration the research trend “emotions, rationality and decision” (Lambie & Marcel, 2002) according to which every-medium and long-term goal must undergo to review according to deliberative rationality, which often takes place in argumentation, and this process is strongly influenced by aware emotions.

4. Corpus and methodology

Concerning the corpus, data were collected at the highly specialized practice of oncologic pancreatic surgery at the Hospital of Verona (Italy), where patients arrive after a diagnostic day-hospital. In order to support the main claim of the paper, namely that the awareness of doctors’ emotions and the consideration of patients’ expected emotive reactions emerging in argumentation strongly influence the final outcome of the medical consultation, data were collected looking at the threefold perspective of the doctor-patient interaction, of the doctor-psychologist interaction, and of the patient-psychologist interaction. Indeed, data consist of audio-recordings of 15 doctor-patient interactions concerning the moment of the disclosure of the bad news of the impossibility to surgically intervene, of 15 doctor-psychologist interactions about doctor’s emotive resonance after the communication of the news, and finally of 15 patients-psychologist interactions about the emotive reactions after the news communication and the impressions about the way in which the doctor managed the painful communication. The first type of data permitted an in-depth analysis of argumentative dynamics, whereas the second and the third type of data permitted to have a confirm of the claim through a retrospective clue.

The methodology used for the reconstruction of argumentative structures at the interactional level follows Pragma-Dialectics, whereas for the analysis of the inferential structure of arguments I use the approach known as Argumentum Model of Topics (Rigotti & Greco Morasso, 2010).

5. A case study: highly specialized medical consultation after a diagnose-oriented day-hospital as a peculiar activity type

According to Van Eemeren stating that “the various communicative activity types are empirical conceptualizations of conventionalized communicative practices” (Eemeren van, 2010, p. 145), I propose to conceive the “highly specialized medical consultation after a diagnose-oriented day hospital” as a peculiar activity type with its own specific characteristics and purposes, resulting in an activity type, which is clearly different from the other types of medical consultations. With reference to this, in inoperable oncologic patients, we can identify three stages of this peculiar activity type, namely the stage of the communication of the impossibility to surgically intervene, the stage of the communication of the need to do a chemotherapy and the phase of the choice of the most suitable chemotherapy. A peculiarity of this activity type can be identified in the fact that when patients arrive to the consultation, it is the second time that patients see the doctor (patients met the doctor during the day-hospital), so that the stage of the patient examination and clinic history has already been made during the day-hospital.

Furthermore, it is important to notice that the communication of the impossibility to surgically intervene represents a very highly emotive interaction due to the painful communication of the bad news disclosure referring to the impossibility of an effective cure.

In order to carry out the main aim of the study, the features of the phases of the two distinct types of interactional approaches in managing the communication in this activity type were identified. On the one hand, concerning the patient-centered approach, we can find the following features; patients’ awareness degree concerning illness’ construal is ascertained, the bad news communication of the impossibility to do a curative surgical intervention follows, and lastly the most suitable treatment is discussed and negotiated, so that patients’ opinion is taken into account and is endorsed. In this interactional approach doctors show a great ability to argue and to use emotions in argumentations as well as to show an empathic behavior. On the contrary, the features characterizing the disease-centered approach are the following; patients’ awareness degree concerning the disease is not ascertained, bad news communication follows, and the most suitable treatment is given as a factual data, without discussion and negotiation. We observe in the best cases the presence of an only poor argumentation, and emotions, both of the doctor and of the patient, are not taken into consideration.

5.1 Patient-centeredness: an argumentative analysis

In what follows I will show three argumentative reconstructions pertaining to a patient-centered interaction; the first one shows the standpoint of a patient after that the doctor has communicated him the impossibility of the surgical intervention at the moment, the second one shows the doctor’s standpoint after the communication of the bad news, and the third one shows the doctor’s standpoint during the phase of the choice of the most suitable treatment.

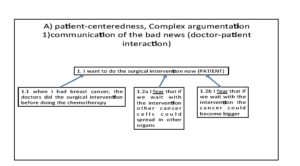

In the first argumentative reconstruction the standpoint of the patient “I want to do the surgical intervention now” is supported by the argument of analogy “when I had breast cancer the doctors did the surgical intervention before doing chemotherapy” and by two emotive arguments “I fear that if we wait with the intervention other cancer cells could spread in other organs” and “I fear that if we wait with the intervention the cancer could become bigger”, as shown in table 2:

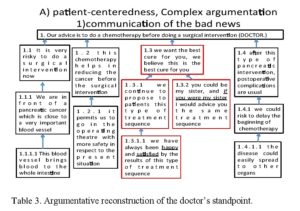

In what follows I will illustrate the argumentative reconstruction of the doctor’s argumentation; the standpoint “our advice is to do a chemotherapy before doing a surgical intervention” is justified by four argumentative lines, as we can see in table 3: the first argues about the danger of doing a surgical intervention at the present moment, the second argues about the utility to do a chemotherapy before the surgical operation, and the third acts on emotions. On the one hand the assertion that doctors want the best cure for the patient is justified by 1.3.1, and in the last analysis by 1.3.1.1. On the other hand the argument that doctors want the best cure for the patient is justified by the subordinate argument 1.3.2, where we can observe an empathic behavior. Finally the fourth argumentative line, brings reasons in favor of the impossibility to do the surgical intervention at the present moment.

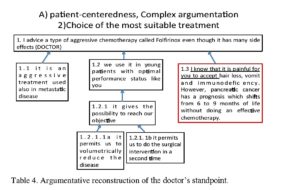

Finally, in the last phase, namely that of the choice of the most suitable treatment, the doctor’s standpoint is “I advice a type of aggressive chemotherapy called Folfirinox even though it has many side effects”. In order to justify the importance of doing this aggressive treatment, the doctor proposes three argumentative lines; the last one lays stress on the doctor’s consciousness of the emotive state of the patient, which attempts to make the argument more acceptable for the patient, as we can see in table 4.

The analysis of a patient-centered medical interaction based on the awareness of doctor’s emotions and of the patient’s possible emotive reactions as well as on an empathic behavior demonstrates that emotions emerging in argumentation play an important role in supporting patients in bad news disclosure as well as in guiding patients about the decision making process of treatment choices; in this framework the most important criterion are patients’ preferences. Such kind of interactions favor a shared decision making process

aimed at reaching a treatment on which both physician and patient agree, by discussing the pros and cons of possible treatment options in such a way that the views of both parties are taken into account

as stated by F. Snoek Henkemans (Snoek Henkemans, 2012, p. 30). Furthermore they enable

a reasoned compliance of the patient, where the patient takes a certain course of action advised by a doctor because she has understood and believes in the inner motivations behind it

as stated by Rubinelli and Schulz (Rubinelli & Schulz, 2006, p. 357). What is more, this approach permits to support the emotive involvement of the patient during the bad news disclosure as well as during the decision-making process of the treatment choice.

We can find a confirm of these statements from a retrospective clue in the doctor-psychologist interaction about the doctor’s emotions during the bad news communication, as we can see from the excerpt below;

(1)

Ps: how did you feel during the communication of this bad news?

D: I felt at ease because I had already introduced the discussion about a possible cancer during the previous visit..

Ps: what emotions do you feel now?

D: I must admit that sometimes I feel very sad in communicating the bad news, when patients have the same age of me, as in this case… I sometimes empathize

The importance of emotions’ awareness is confirmed by the evidence of the fact that the doctor is aware of his own emotions and succeeds in an empathic behavior.

We find another confirm of the importance of argumentation from another retrospective clue in the psychologist-patient interaction about the outcome and impressions of the bad news communication after the consultation, as we can see from the excerpt below;

(2)

Ps: and did you understand why it is important to do chemotherapy before the surgical intervention?

P: yes I understood that doing chemotherapy is important in order to let the cancer decrease and to do the surgical intervention in a second moment

Ps: was it important for you to hear about this?

P: Yes the doctor was very clear in clarifying many aspects of my disease and of the cure the exams confirmed the presence of a carcinoma however nobody told us why it was important to do chemotherapy first and wait with the surgical intervention

5.2 Disease-centredness: doctors disregarding their own emotions and patients’ emotive reactions

In order to highlight the potential benefits of the patient-centered approach, I will hereby illustrate the inadequacy of the disease-centered approach: we will show some excerpts in which it is evident that the doctor does not argue in favor of his standpoint, and that this causes misunderstandings in the communication, because the patient does not understand the actual situation and does not have the possibility to ask for questions and remarks, as stated also by S. Bigi (Bigi, 2012). Furthermore, the doctor does not take into consideration the possible emotive reactions of the patient and this clearly contributes to misunderstandings. It is remarkable the case of a patient that did not want to do the surgical intervention after chemotherapy because she did not understand that it was the most effective cure. The day after the consultation the patient came back for another consultation because she did not want to do the surgical intervention after chemotherapy and she was confused about the therapeutic approach to follow, as we can see from the excerpt below;

3)

P: Yesterday I asked you if it was possible to avoid the surgical intervention and you answered me that I absolutely need to do this intervention, without explaining me why.

Then, the patient goes on arguing why she did not want to do the surgical intervention, and the doctor answers “I only wish you that we meet in the operation theatre”, as we can see from the excerpt below;

(4)

P: I read that when the cancer is in the pancreas tail, after chemotherapy the cancer may disappear and so I may avoid the surgical intervention

D: I told you yesterday the answer is no. After chemotherapy you must do the surgical intervention.

I only wish you that we meet in the operation theatre.

P: but why?

D: because you may not be candidate to the surgical intervention and then continue with chemotherapy/ the surgical intervention is unavoidable it is the best solution because continuing with chemotherapy is not effective/ the disease could spread in other organs

P: if you wish me that I will be able to do the surgical intervention, then I wish it also myself

The patient asks for reasons and the doctor argues that the patient could not be candidate to the surgical intervention and then continue with chemotherapy, that it is not the best solution because continuing with chemotherapy is not effective. Here we observe a shift in the patient’s reasoning, after an even poor argumentation, which however hints at an empathic response.

Concluding, we can observe that no argumentation or poor argumentation which does not consider doctors’ emotions as well as possible patients’ emotive reactions and which disregards empathy produces misunderstandings and difficulties in accepting diseases’ consequences and treatments. In such a framework, the most important criterion seems to be identifiable in medical evidence, and we observe an unilateral aprioristic decision-making process, where the patient is in passive condition and the doctor decides alone for the patient.

Even in this case we show a confirm of this dis-functional type of interaction from a retrospective clue, namely from the doctor-psychologist interaction about the doctor’s emotions during the bad news communication. The doctor is not aware of his own emotions and is not empathic;

(5)

Ps: the idea to communicate this type of news is painful for you?

D: No, I don’t have any emotive resonance.

Ps: Are you sure? It is impossible.. Are you released?

D: Yes, I am sure. I have already removed the content of the communication.. I do this every day.. I think that this is a sort of defense

We can retrieve another retrospective clue of the importance of an even only poor argumentation hinting at emotions in the patient-psychologist retrospective interaction, as we can see from the excerpt below;

(6)

Ps: do you think the doctor was clearer today in explaining you the clinical situation?

P: Yes today he was clearer and more human… however, yesterday I was very upset about the fact that he wished me to go in the operation theatre.

Ps: probably you were upset yesterday because the doctor wasn’t clear in explaining the reasons of the fact that he wished you to go in the operation theatre. Because if you don’t do the surgical intervention the cure would be only a half cure. Because the best cure consists of chemotherapy and intervention. Because continuing with chemotherapy wouldn’t be effective.

P: Yes now I understand that I must do the intervention and this is all I wish myself.

6. Emotions at the inferential level: the interweaving of psychology and argumentation

Until now this paper focussed on the interactional analysis; however, in order to prove the crucial role of doctors’ emotions in patients’ reasonable decisions, it is necessary to make a more in-depth analysis and to investigate the inferential structure of arguments.

First of all, we need to introduce the theoretical foundations of emotions conceived as evaluative and unifying devices able to connect one argument to its standpoint. Social psychology has argued in favour of the reasonableness of emotions since W. James, who argued that feelings individualize knowledge, telling us how a thing is in conjunction with us, and that feelings unify knowledge, being able to connect past events deriving from our expectations and desires (James, 1884; James, 1890).

In more recent time, the famous neuroscientist A. Damasio reevaluated the Jamesian theory, and lays stress on the necessity of taking into consideration the analysis James made of the “internal world”, in order to shed light on that unified mental configuration which unifies the “objects of the Self” (Damasio, 1999); the central core of his theory concerns the mental evaluation of the situation which determined the emotion.

In this paper I propose that an analysis of the inferential structure of arguments following the approach known as Argumentum Model of Topics (Rigotti & Greco Morasso, 2010) offers a proof of the evaluative and unifying function of emotions as conceived by psychological theories.

The AMT aims at proposing a coherent and founded approach to the study of argument schemes, which can overcome several emerging difficulties, yet being in line with previous achievements on this aspect. In general, modern authors conceive of argument schemes as the bearing structure that connects the premises to the standpoint or conclusion in a piece of real argumentation. In the AMT, the argument scheme combines a procedural (universal and abstract) component, in which an inferential connection (maxim) is activated, with a material component, guaranteeing for the applicability of the maxim to the actual situation considered in the argument (Rigotti & Greco Morasso, 2010). For space reasons, we will focus only on the material component; in the AMT the material component is made up of two components, namely the endoxon and the datum. Endoxa are conceived as “opinions that are accepted by everyone or by the majority, or by the wise men (all of them or the majority, or by the most illustrious of them)” as conceived by Aristotle (Topics 100b, 21). With reference to the datum, it concerns statements that are peculiar pieces of information, concrete facts emerging in the argumentative situation. It is in this framework that I will propose to consider the relevance of emotive endoxa and emotive data.

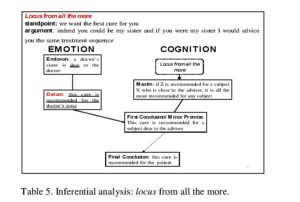

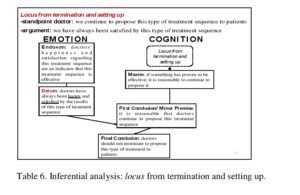

The single argumentation that I will investigate deals with the doctor’s argumentation at the stage “communication of the bad news” of the activity type. The doctor’s standpoint is “Our advice is to do a chemotherapy before doing a surgical intervention”, motivated by the argument “1.1 We want the best cure for you, we believe this is the best cure for you”, which is in turn supported by two compound arguments: according to the taxonomy of loci the first one can be classified as a locus from all the more, “1.1.1a You could be my sister and if you were my sister I would advice you the same treatment”, and the second one as a locus from termination and setting up, namely “1.1.1b since years we continue to propose this treatment sequence to patients” because “1.1.1b.1 we have always been satisfied by this type of treatment sequence”.

I believe that AMT gives the chance to retrieve the evaluative and unifying function of emotions, integrating emotion and cognition in a unified mental configuration; the emotive and the cognitive component of the reasoning process are respectively retrievable in the material and in the procedural component of the argument scheme resulting in the final conclusion when the decision is achieved.

A careful analysis of the locus from all the more through the Y-structure permits to observe the presence of an emotive endoxon and of an emotive datum in the material component. The conjunction of the endoxon and of the emotive datum creates an inferential effect leading to the first conclusion, which is strongly emotionally determined; the first conclusion that is obtained from the material starting point is equally exploited by the procedural starting point. This point of intersection is crucial in the AMT, indeed it represents the junction between the material and the procedural starting points, and within this work the interweaving between the emotive and the cognitive components. This conclusion perfectly meets the conditions established by the maxim and, conjoined with it allows inferring the standpoint “This cure is recommended for the patient”, as shown in Table 5.

With reference to the locus from termination and setting up, I will analyse the single argumentation “we continue to propose this type of treatment sequence to patients” because “we have always been satisfied by this type of treatment sequence”; again, the emotive and the cognitive component of the reasoning process are respecively retrievable in the material and in the procedural component of the argument scheme resulting in the final conclusion when the decision is achieved. Again, from the analysis of this Y-structure we can observe in the material component the presence of an emotive endoxon and of an emotive datum. The conjunction of the endoxon and of the datum creates an inferential effect leading to the first conclusion “doctors should not terminate to propose this type of treatment sequence”. Again, this conclusion perfectly meets the conditions established by the maxim and, conjoined with it allows inferring the doctor’s standpoint.

7. Conclusion

With this paper, I have contributed to the current debate on the importance of adopting a patient-centred approach in highly emotive medical communicative situations such as highly specialized medical consultations; for this purpose, I proved the crucial importance of argumentation and of argumentatively played out emotions.

Firstly, I have shown the importance of the awareness of doctors’ argumentatively played out emotions in the optimization of the management of the painful communication, in tracing a particular and an effective path in decision-making processes of the patient and in helping the acceptance of the disease’s consequences in terms of both treatments and prognosis.

Secondly, I have shed light on the necessity of taking into account patients’ emotions and possible emotive reactions, in order to manage an optimal painful communication and to favour the acceptability of doctors’ arguments in the patient.

Thirdly, I have shown that the AMT approach gives us the chance to retrieve the evaluative and unifying function of emotions in the inferential structure of arguments, as conceived by psychological theories, integrating emotions (conceived as processes of cognitive evaluation) and cognition in the reasoning process, reflecting a unified mental configuration.

However, much remains to be done, and future work should be devoted to better analyse the relationship between doctors’ empathy and arguments’ acceptability for patients. At the inferential level, the correlation between empathy and locus from all the more should be deepened also with a quantitative study.

On the other hand, the role played out by patients’ emotions should be emphasized and investigated more in depth; the relationship between patients’ argumentatively played out emotions and their standpoint may lead us to better understand some defense dynamics leading to the refutation of doctors’ standpoints for instance, aiming at finding out if a correlation exists between patients’ experienced emotions and the acceptability of doctors’ argumentation.

References

Bensing,J. (2000) Bridging the gap. The separate worlds of evidence-based medicine and patient-centered medicine. Patient education and counseling, 39, 17-25.

Bigi,S. (2012), Evaluating argumentative moves in medical consultations, Journal of Argumentation in Context, 1:1, 51-65.

Cigada,S. (2008), Les èmotions dans le discours de la construction europèenne, Milano: Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore.

Damasio,A. (1994), Descartes’ error: emotion, reason, and the human brain, New York: Gosset/Putnam Press.

Damasio,A. (1999), The feeling of what happens. Body and emotion in the making of consciousness, London: Vintage Books.

Edwards, A. & Elwyn G. (2009). Shared decision-making in health care. Achieving evidence-based patients choice, Oxford: Oxford Univesity Press.

Eemeren, F.H. van, Grootendorst, R., & Snoeck Henkemans, A.F. (2002). Argumentation: Analysis, evaluation, presentation. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Eemeren, F.H. van, & Grootendorst, R. (2004). A systematic theory of argumentation: the Pragma-dialectical approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Eemeren, F.H. van, Garssen, B., Meuffels, B., (2009), Fallacies and judgements of reasonableness, Dordrecht: Springer.

Eemeren, F. H. van, (2010), Strategic maneuvering in argumentative discourse, Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

James, W., (1884), What is an emotion?, Mind, 9:34, 188,205; Oxford University Press on behalf of the Mind Association.

James, W., (1890), Principles of psychology, New York: Henry Holt and company.

Lambie J.A. & Marcel A.J., (2002), Consciousness and the varieties of emotion experience: a theoretical framework, Psychological Review, 109:2, 219-259.

Lambie, J.A., (2008), On the irrationality of emotion and the rationality of awareness, Consciousness and cognition, 17:3, 946-971.

Lambie, J.A., (2009), Emotion experience, rational action, and self knowledge, Emotion Review, 1:3, 272-280.

Macagno, F. & Walton, D., (2014). Emotive language in argumentation, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mead, N., & Bower, P. (2000). Patient Centredness. A conceptual Framework and review of the empirical literature, Social science and medicine, 51, 87-100.

Plantin, C., Doury, M., Traverso, V., (2000). Les emotions dans les interactions, Lyon: Presses universitaires de Lyon.

Rigotti, E. (2006) Relevance of context-bound loci to topical potential in the argumentation stage, Argumentation , 20 (4), 519-540.

Rigotti, E. (2005), Congruity theory and argumentation, Argumentation in Dialogic Interaction, 75-96.

Rigotti, E., & Greco Morasso, S. (2010). Comparing the Argumentum Model of Topics to Other Contemporary Approaches to Argument Schemes : The Procedural and Materal Components , Argumentation, 24, 489-512.

Rigotti, E., & Rocci, A. (2006). Towards a definition of communication context. Foundations of an interdisciplinary approach to communication, in The communication sciences as a multidisciplinary enterprise, ed. by M. Colombetti, Studies in the communication sciences 6 (2), 155-180.

Rigotti, E. & Rocci, A. (2001). Sens-non-sens-contresens, Studies in Communication sciences, 1, 45-80.

Rubinelli, S. & Schulz, P. (2006). ‘Let me tell you why!’. When argumentation in doctor-patient interaction makes a difference, Argumentation, 20, 353-375.

RPSGB (Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain). (1997). From compliance to concordance. Achieving shared goalsin medicine taking, London.

Rubinelli,S., & Zanini,C. (2012) Teaching argumentation theory to doctors, Journal of Argumentaion in Context, 1:1, 66-80.

Schulz, P., & Rubinelli,S. (2008) Arguing ‘for’ the patient: informed consent and strategic maneuvering in doctor-patient interaction, in Argumentation, 22, 423-432.

Smith, R.C., Marshall, D., Lyles, J. & Frankel, R.M. (1999), Teaching Self-Awareness enhances learning about patient-centered interviewing, Academic Medicine, 74, 1242-1248.

Snoek Henkemans, A.F., & Mohammed,D. (2012). Institutional constraints on strategic maneuvering in shared medical decision-making, Journal of Argumentation in Context 1:1, 19-32.

Walton, D. (1992) The place of emotion in argument, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

You May Also Like

Comments

Leave a Reply