ISSA Proceedings 2014 ~ The Persuasive Powers Of Text, Voice, And Film – A Lecture Hall Experiment With A Famous Speech

Abstract: This paper presents and discusses a lecture hall experiment concerning the rhetorical impact of different media. The experiment brings out notable differences in the effects of persuasion and argument embedded in the same set of words – in this case an extract from a historic speech – when presented respectively in writing, as speech, and on film.

Keywords: argument, experiment, film, mountaintop, persuasiveness, rhetoric, soundtrack, text, visual, voice.

1. Introduction

For a number of semesters I have conducted a lecture hall experiment with international university students about persuasion and argument and how they appear to differ in their impact, dependent on whether they are presented in writing, as speech or on film.

It is hardly surprising that the medium used to present a text can influence how its message is perceived by an audience, but the eye-opening trick of this experiment is that I present my students with exactly the same “text” or “content” in each case, first in writing, then as a voice recording, and finally on film. The students’ conceptions and evaluations of each type of presentation of the “text” alter dramatically as it changes from reading mode to listening mode and then to film-viewing mode. Naturally film-viewing here includes the sound track with its associated background sounds and voices heard among the audience.

2. Persuasive features of the text

The piece of text that I use is taken from a fairly well known speech, but I have deliberately chosen a part of it that does not give the orator, the context or the situation away too obviously. I want the students to focus first on the text as written material, tell me what it says, how it is structured and styled, and how it affects them. I also ask them not to let it be known, at this point, if they have recognized the text or are able to make an intelligent guess either as to its origin or who wrote it. I then ask them whether they have found any sound arguments in the text and whether, and in what manner, they find it persuasive. The text runs as shown in figure 1:

Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land!

And so I’m happy, tonight.

I’m not worried about anything.

I’m not fearing any man!

Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord!!

(Figure 1: This is the text image that I project on the screen in the lecture hall[i])

At first the students often hesitate, probably because they suspect that I am setting some sort of trap or test, and also because they do not find the text particularly clear or easy to categorize. I often have to help a little with getting them started on what could be called a common pragmatic analysis, or an analysis of the content and form of the text. For example, I may ask them what sort of text it seems to be: is it like a love letter? Is it perhaps more like a note from one’s bank about some problem with an account? Or is it perhaps an announcement from their university about upcoming exams?

At this point the students often say that the text looks more like part of a speech or perhaps a sermon. I ask them what the indications of that are, and they will then say that there are a number of short sentences, such as are to be found in an oral presentation, and also that there are some religious references such as “God” and “the Promised Land”, the latter referring to the story from the bible about Moses leading the Jews to the ‘Promised land’ or to “what they considered” the ‘Promised Land’ (International students in my classes are often very cautious when it comes to matters touching on political correctness!).

When asked for more comment about the style of the text they note points such as the clause “I’m not” as opposed to “I am not” as further indications that it is a transcript of a speech. The speaker’s use of the phrase “Mine eyes” instead of “My eyes” seems to make the mood of the text rather solemn, as do the words about doing “God’s will”.

Further encouraged, the students may also mention the alliteration in “Like to Live a Long Life”, and also how many phrases start with the same first word “And” (anaphora).

When asked about possible arguments in the text the students are as a general rule unable to identify any, but with a little help they can reconstruct at least an example of an incomplete one: “I have seen the Promised Land, because I have gone up to the mountain” (the unstated but implied second premise – the “warrant” in Toulmin’s terminology – would be something like: “From the mountain you can see very far/ see the Promised Land”). However they find this unclear, and consequently unconvincing as an argument. All in all the students do not seem to feel that the text has convinced them, or to put it another way they do not see that it has any significance for them: they do not feel moved or touched by it. Once a student went so far as to say that it was just a lot of egotistical religious nonsense that ‘left him cold’.

3. Persuasive features of the voice

I then tell the class that I am, so to speak, going to add a voice to the text – in the form of a soundtrack – while the same text is still projected onto the screen. I further ask them to reflect while they listen, and consider whether the voice in any way changes their perception of the text, especially with regard to its argumentative or persuasive qualities.

Figure 2: This pictogram is added next to the text in figure 1, and in the experiment this enables the soundtrack to be played.[ii]

Figure 2: This pictogram is added next to the text in figure 1, and in the experiment this enables the soundtrack to be played.[ii]

As I play the soundtrack it is usual for quite a few students to ‘light up’ as they recognize the voice, but again I ask them not to mention the fact or name the speaker and remind them to try to characterize the voice.

That sometimes appears to be rather difficult for them, until I point out that obvious features, such as whether it sounds like a male or female voice, would be relevant. ‘Of course, it is a male voice’, they say, and add that it has an American accent. Some even identify it as being spoken in a Southern dialect and add that it sounds like a black preacher from the 1960’s.

And indeed it is, namely Martin Luther King. By now most of them have guessed that, and that in turn seems to make it easier for them to characterize the voice. But I then ask them to consider in principle just the voice that lies before them, by trying to abstract from background knowledge and simply focusing on such qualities as they can detect in the voice itself.

They mention that the speaker sounds very dedicated and sincere, and that he has a peculiar way of enhancing, or prolonging, certain words and vowels, almost as though he is singing or chanting.

We can then agree that hearing the speaker’s voice adds quite a lot of “information” (or one could say in terms of rhetoric that it adds heavily to the ethos of the text), i.e. in this case we are convinced that it is a man speaking, but also that he is very engaged and eager to convince his audience. When I ask them how exactly it is that they have received this impression – which qualities or features of the soundtrack reveal this “dedication”, they may answer that they just feel it very clearly: there is something compelling about the speaker’s intonation, the modulation of his voice, and its loud, stentorian quality.

We can also agree that while it is quite difficult to describe a voice in detail – and we are not used to doing so – we are nevertheless very good at recognizing different voices. We do not need to listen for many seconds in order to identify the voice of a friend or family member, or of someone who often appears in the media: we can do it in a split second, and can often, just as instantly, recognize the mood or emotion of the person speaking, even though we may not have much by way of analytical tools, precise concepts or academic terminology at our disposal.

And the qualities of the voice directly affect our own moods, perceptions and attitudes. We do not have to wait for a careful analysis or a “reading of the whole text” in order to take away an impression and be influenced by the voice: it makes its impact immediately.

Pushed for more information from the soundtrack in question, the students add that they can clearly hear the response of the audience in the room where the speech is being given, – and from it get the impression of a very enthusiastic interaction between the speaker and the audience, something quite absent in the written text.

Of course a careful transcript could have added notes about applause from the audience and the several cries of “yes!” from within the room, but again such a transcript could never describe the actual audio experience and might well be felt to be inauthentic. The written text cannot deliver the “live” experience, whereas the soundtrack feels immediate and has “presence”. The text, as text, can be read either slowly or fast, and can be repeated, broken up and analyzed; the soundtrack, however, flows in a sequence that normally takes the natural pace of the events it records. We can of course break it up, change the speed and manipulate it, just as we can manipulate and edit a written text or a film. But in listening we experience the feeling of something happening “right now”, even though what the listener is hearing may be a historical recording.

A written text can to some extent come to life as we read it, but that requires a special type of imaginary activity on the part of the reader. Half an empty page and a word in capital letters will seldom cause a reader to jump from his seat, whereas a long pause or a sudden loud sound on a soundtrack would normally cause an immediate physical reaction of surprise or shock among an audience.

Anyway, at this point I can agree with the students that the soundtrack, to a much greater extent than the written text, gives us a feeling of being present and of participating in an event with other people. The speaker seems in a sense to include us in his audience, even though we realize full well that we were not present when he was speaking. The voice reaches out to us, trying to convince us of something.

This may not be the case with another voice. As an illustration I sometimes read the text out loud, and my voice sounds very flat, monotonous and unenthusiastic compared with Martin Luther King’s. And the students agree that my reading of the text has quite a different, even ridiculous, effect. It is in no way convincing; it presents the listener with quite a different type of speaker, one whose voice does little by way of communicating either the message or its appeal.

4. Persuasive features of the film

I then ask the students to observe how their experience and evaluation changes when I project a film clip that covers the same text (including naturally the soundtrack they have already heard).

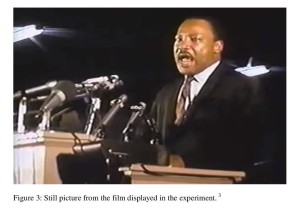

Figure 3: Still picture from the film displayed in the experiment.[iii]

While projecting the film I can see quite clearly that the students become much more attentive and emotionally involved than when they were simply reading the text or listening to the sound track. When interviewed about their experience they readily admit this, and lay stress on his eyes and his very intense eye contact with the audience. His eyes seem to shine brilliantly, almost superhumanly, almost as if he were about to burst into tears. They also mention his energetic gestures and commanding posture.

When pushed a little further they tell me that his formal black and white clothing add to the mood of the film clip, as do the dark back ground and the spot light on the speaker. Sometimes I can even nudge them into noticing the angle from which he is being filmed, with the camera ‘looking up’ at him, emphasizing his appearance as a preacher, or father figure.

When I ask what more information or “material” they can get from viewing the film (besides what they have already mentioned about the speaker being a black male, dressed in such and such a fashion and looking thus and so), the students may recall that there are also a few short shots that include the audience. If I then search out one of these shots and pause the film there they tell me that they get the impression, even more so than from the sound track, of an enthusiastic audience; and note that it was a mixed audience of men and women, black and white, old and young. And from the clothes and the setting we get an idea of when and where the speech was given (some decades ago in America).

Figure 4: The film clip gives us more information about the audience and the setting.

At the very end of the film clip we get a shot that is almost ‘backstage’: the camera has zoomed out, and in this shot we see the speaker leaving the podium and being greeted or thanked, by his friends or staff.

Figure 5: Here the camera shows us what happens ‘backstage’.

So when asked to comment on this, my students – being well versed in the academic slang of our Communication department – can tell me that the film clip offers us more information about the context and setting of the speech, elements that were missing in the written text – and some explanatory notes would be needed if one were to evaluate the written text properly. But even so the film clip still appears to offer us, in a much more realistic sense than the other types of presentation, the historical and cultural circumstances; and most notably, a sense of almost being present.

I then ask my students whether the camera is merely registering everything that is there, or if it is playing an active role in portraying the speech. This may of course lead to a long discussion about the nature of film and the genres of reportage and documentary, but I try to keep such digressions short. I often get the answer that certain camera angles have been chosen for effect and that not everything relevant to the occasion is shown, and that one can conclude therefore that the camera and film editing have a certain rhetorical power in shaping our perception and understanding of the event. And that certain things are missing on the film: if you had actually been in the room you would have had a direct sensation of the atmosphere; e.g. the smoke, the smell of the room, the temperature, the roughness and texture of the floor and of the seat you were sitting on.

As I show the film clip again I ask the students to pay special attention to what is happening towards the end of it. This time they notice a limited, rather shaky, amount of zoom-in onto the face of the speaker. This reveals of course the hand of the filmmaker making an adjustment to the camera – and could be seen either as a sign of poor practice, or else as an attempt by an experienced filmmaker to highlight what he feels to be the approaching climax of the speech. Very often when filming one moves in closer with the camera when the most intense moment arrives – or alternatively, by “moving in closer” one actually helps to create an important moment in the film.

Figure 6: This illustrates the framing of the subject and the camera’s distance from it during most of the speech.

Figure 7: Towards the (anticipated) climax of the speech the camera tries to move in a little closer; the result is neither particularly smooth nor steady but that in itself seems to add to the effect of a climax. It is a feature seldom noticed by the students during the first run of the film clip.

5. The historical speech event

At this point I tell the students – if it has not been revealed before – a little more about the speaker and the context: that it is indeed Dr. Martin Luther King, and that the quoted text is from his last speech, (now known as the “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech), given on April 3rd, 1968 in Memphis, Tennessee; and I remind them that in 1964 King had become the youngest person to receive the Nobel Peace Prize for his work towards ending racial segregation and discrimination through civil disobedience and other nonviolent means. To younger generations, and because it has often been quoted from and reported on film and TV, King is nowadays perhaps best known for his “I have a dream” speech of August 28, 1963, given at the Lincoln Memorial, Washington. He was assassinated the day after the ‘Mountaintop’ speech, on April 4, 1968, in Memphis.

This background information adds of course to the experience, to our emotional response to the words as well as to the film as a whole. Some students argue that it seems obvious now that he actually knew that some ‘bad guys’ were out to kill him and that this is revealed both by his words “I may not get there with you”, and by his eyes and whole appearance. Others will say that it is easy to over-interpret and read things into a text or a film when you already know the chain of events and the historical circumstances.

At this point it usually becomes clear that we are talking about four different things here: the written text we saw first, the soundtrack of Dr. King’s voice, the film clip recording his speech, and the 1968 event itself.

The students and I are now agreed that in this case going from the written text to the soundtrack and then on to the film clip greatly increases the persuasiveness and impact of the speech, and at this point it would be tempting to ask the students if they feel that being present at the actual speech event would have left an even stronger impression on them. But that, of course, would be inviting speculation about what could well become a very muddy case, so I usually refrain from it.

But I might add a comment that one’s actual presence at the historical event in that room should not be considered critical or decisive when it comes to making an assessment of the persuasiveness of the speech, as in that case one’s assessment would depend, naturally enough, on whether one was there as a black boy in the front row, a sleepy old woman at the back, a white policeman on duty, or a member of the organizing committee worrying about possible riots. And one’s individual perception and appreciation of the performance of the speaker, his gestures and his words, would depend on a number of other factors. But as a point of departure for an academic content analysis we have to look at those features that are actually there and that we can agree upon are there (as belonging to the written text, the voice recording, and to the presented film). The next step will then be to try to come up with a reasonable interpretation that others will accept too.

6. Conclusion

The whole lecture hall experiment described above is actually meant as a warm up exercise for students about to engage in further studies of Print Media production, Speech, and Video Production, as well as further studies in the analysis of Communication and Rhetoric. As such it leaves many aspects unexplored, but it may also give a certain overview of some constituent persuasive features in different media:

First of all an actual (unmediated) speech event is dependent – as we already know from Cicero’s pentagon – on certain complex interwoven features if it is to be apt and persuasive: the speaker, the audience, the situation, the subject and the language. In this case what stands out is of course Martin Luther King as an eminent speaker, but then again it can be argued that he is also speaking at a crucial moment to a highly motivated audience. It can be described as an almost paradigmatic rhetorical situation.

The film reporting from that speech event is in a sense missing something: it is restricted to only two senses, the eyes and ears, and it has to employ specific camera angles and camera framing, specific microphone distance and quality, and typically the film last for a shorter time span than the actual event. So the film media seem to give us a “thinner” experience than that of being actually present. But then again, the features of camera and editing techniques can provide a degree of enhancement and dramatic dynamics to the event. It is not just ‘representing’ in the sense of duplicating, but actually arranging, stressing, explaining, condensing, pointing and offering the event to a new audience. The film maker’s work can to a large extent be understood as an extra layer of rhetoric on top of what is already supplied by the speaker – as when the camera zooms in to “highlight” the climax of the speech, or what is happening backstage.

The soundtrack played alone without projecting the film reveals the quality of the speakers voice as well as the background noise in the room. This gives “more” information and appeal than we get from just reading the transcript, but it can also in some cases even emphasize and enhance the purely ‘audio’ qualities of the speech to a greater extent than what we usually experience when perceiving the complete film clip. Sound is very important to film, as we all know, and sometimes a soundtrack can become even more impressive when the images are not seen.

A written text may seem to come out of this experiment as a very weak medium in terms of persuasion and appeal. But that would be a misleading generalization. Written texts can be persuasive and moving in their own way. Certainly there are beautiful poems and novels that are hard to transform into films of equal beauty or impact, and some argumentative texts are better understood and appreciated when they can be read and re-read than when they have simply been heard. Written texts have features such as layout, fonts, and punctuation that may also enhance their meaning, and possibly also their persuasiveness.

So the conclusion I pass to my students is that the casual ranking of the various media in terms of how effective they appear to be in their ability to persuade, to convince, to argue and to communicate, is a mistake that should be avoided. Rather I encourage them to investigate very closely all of the different persuasive aspects of the particular medium they chose to explore in their upcoming workshops in media production and analysis.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank the bachelor and master students, semesters 2010 – 2014, on the International Track of Communications Studies at Roskilde University, Denmark, for having endured this lecture hall exercise and for contributing valuable comments. The author further wishes to thank Rae Duxbury for advice concerning the formulations in English.

NOTES

i. This text is a transcript of the last part of the speech that is presented more fully on the following pages and in the notes. In order to give a fairly realistic presentation of the lecture hall experiment the origin of the text is not revealed at this point even though it would be the usual correct academic practice.

ii. The soundtrack is not embedded in the text here, but it can be played by using the video-link in the following notes – and to be realistic in terms of the lecture hall experiment one should not look at the video while playing, but only listen to the sound while looking at the quoted text above.

iii. The film clip can be seen at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Oehry1JC9Rk

References:

Juel, H. (2004). The Ethos and the Framing – a Study in the Rhetoric of the TV camera. An essay on the author’s web-page: http://akira.ruc.dk/~hjuel/.

Juel, H. (2006). Defining Documentary Film, “p.o.v.”. Number 22. A Danish Journal of Film Studies, University of Aarhus.