ISSA Proceedings 2014 ~ Where Is Visual Argument?

Abstract: Argumentation studies suffer from a lack of empirical studies of how audiences actually perceive and construct rhetorical argumentation from communicative stimuli. This is especially pertinent to the study of visual argumentation, because such argumentation is fundamentally enthymematic, leaving most of the reconstruction of premises to the viewer. This paper therefore uses the method of audience analysis, frequently used in communication studies, to establish how viewers interpret instances of visual argumentation such as pictorially dominated advertisements.

Keywords: advertising, images, pictures, reception studies, reconstruction, rhetoric, visual argumentation

1. Audiences and the reconstruction of pictorial argumentation

The reconstruction of pictorial and visual argumentation has been pointed out as especially problematic since pictures neither contain words or precise reference to premises, nor has any syntax or explicit conjunctions that coordinate premise and conclusions. Researchers have been critical of speculative reconstruction of visual premises and arguments that are – they claim – not there; or at least that we cannot know for sure are there. So a central question becomes: Where is argument? Or rather where is visual argument?

I propose that we should more often turn to studies of audience reception; because if an audience actually perceives an argument when encountering an instance of visual communication, then surely an argument has been provided.

The first audience analysis must have been Aristotle’s description of the various types of human character in the Rhetoric. However, in rhetorical research empirical audience analyses are rare, and in argumentation studies they seem to be completely absent. More than anything rhetorical argumentation research is text focused.

When rhetoricians actually discuss the audience, they are mostly concerned with the audience as theoretical or textual constructions. They examine the universal audience (Perelman & Olbrechts-Tyteca 1969), the second persona (Black 1998), the audience constituted by the text (e.g. Charland 1987), the ignored or alienated audience (e.g. Wander 2013), or they theorize about the audience’s cognitive processing of messages (W. Benoit & Smythe 2003).

Instead of limiting ourselves to such textual and theoretical approaches, I propose that research into rhetorical argumentation should more often examine the understandings and conceptualization of the rhetorical audience. From mostly approaching audience as a theoretical construction that are examined textually and speculatively, we should give more attention to empirical explorations of actual audiences and users.

When argumentation theorists discuss the audience mostly they engage in discussions about the identity of the audience and the (im)possibility of determining the identity of the audience (Govier 1999, 183 ff.; Johnson 2013, Tindale 1992, 1999, 2013). Because it is hard to define or locate the audience aspirations to examine audiences are sometimes countered with the argument that such studies are futile, because we cannot really know who the audience is. Trudy Govier, for instance, in her book The Philosophy of Argument, questions how much audience “matter for the understanding and evaluation of an argument”. She introduces the concept of the “Noninteractive Audience – the audience that cannot interact with the arguer, and whose views are not known to him” (Govier 1999, p. 183).

The mass audience, which is probably the most typical audience in the media society of our days, is “the most common and pervasive example of a Noninteractive Audience”. The views of this noninteractive and heterogenous audience, Govier says, are unknown and unpredictable (Govier 1999, p. 187). This means “trying to understand an audience’s beliefs in order to tailor one’s argument accordingly is fruitless” (Tindale 2013, p. 511). Consequently, “Govier suggests, it is not useful for informal logicians to appeal to audiences to resolve issues like whether premises are acceptable and theorists should fall back on other criteria to decide such things”.

Ralph Johnson, continues this line of reasoning, and proposes that a Noninteractive audience is not only a problem for pragma-dialectics, as Govier suggests, but also for rhetorical approaches; because it is not possible to know this type of audience. Johnson criticises the views of Perelman and Christopher Tindale, which holds, “the goal of argumentation is to gain the acceptance of the audience” (Johnson, p. 544). Advising a speaker to adapt to the audience when constructing arguments, says Johnson “is either mundane or unrealistic” (Johnson 544). It is unrealistic because, we cannot truly grasp an audience as an objective reality.

Johnson is right in saying that grasping an audience, understanding and defining its identity, is a difficult matter. However, while this issue of the audience might be a problem for the speaker, it need not cause so much anxiety for the researcher. Because, the desire to determine the identity of the audience is, I think, is not the most fruitful way to an understanding of how rhetorical argumentation works. Desperately seeking the audience (cf. Ang 1991) is not the way forward.

I am not arguing that researchers should stop speculating about what an audience is, nor do I claim that speakers should refrain from defining their audience and adapt their messages accordingly. But, I am arguing that the primary concern for scholars of rhetoric and argumentation should not be to determine the exact identity of the audience or settle whether or not an argument, or another instance of rhetoric, creates adherence.

What we should be more concerned with is how an argument or any rhetorical appeal is constructed, how it is audience-oriented, and – which is the main point of this paper – how it is received, interpreted, and processed – that is: how actual audiences actually respond to instances of rhetorical argumentation.

As pointed out by Edward Schiappa (2008, p. 26): “We need to find out what people are doing with representations rather than being limited to making claims about what we think representations are doing to people.” This requires a combination of close readings of rhetorical utterances, contextual analyses of the situation, and empirical studies of audience reception and response. This is why I have done reception studies of ads exploring the responses of focus groups to pictures and pictorially dominated ads.

2. Focus group studies

Through focus groups I have attempted to find out if respondents perceive arguments in the advertisements, how they perceive them, and tried to explore in this way the characteristics of visual argumentation. The three focus group interviews carried out for this essay were done in Norway during June 2014. The groups consisted of, respectively, six pensioners in their 70s, five young women aged 18-19, and four university students that did not know each other. The groups were selected in order to allow for variation and breadth in knowledge and life situation.

The respondents were first introduced to each other and the focus group situation, and then asked to fill out a short survey with relevant personal information. They were then explained that I as researcher was interested in hearing what they thought about some images that I wanted to show them. They were not told that I was particularly interested in visual argumentation. I explained that I would first show them five pictures, each for less than one minute, and requested that they during this they should write five words or short sentences about the first thoughts that came to mind when they saw each picture.

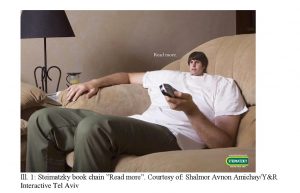

When this activity was done, I instigated focus group conversations with open questions such as “What do you think when you see this picture”, and open follow-up questions such as “why?” or “how?” Other pictures than the one mentioned in this paper were shown to the respondents and discussed during the focus groups. One of the advertisement I examined was this one, from the Israeli bookstore Steimatzky.[i]

When I asked a young group of women the age of 18-19 what we could say about this ad the first respondent immediately said:

You lose intelligence by watching television, because your head becomes smaller by that (MI/AN 5:33)[ii].

Another respondent followed up:

I think that you become more focussed on watching television, than building knowledge by reading. So, according to the advertisement the head will become smaller and smaller when watching television. However, it will become larger and larger by reading books. (MI/AN 05:55)

When asked what the ad proposed, most of the young women answered: “Read instead of watching TV” (MI/AN: 07:21). When I asked why one should read; the young women generally responded something in the lines of either: “Because reading makes you smarter” (MI/MA 06:52), or “Because watching television makes you stupid” (MI/JA: 05.55).

In a group of pensioners in their 70s the first response to my question “What can we say about this picture” was: “That you should read instead of watching television” (BR/UN 09:37).

When a respondent from a group of university students, saw the ad, a male respondent immediately said, “it implicates that if you don’t read you will become stupid” (MA/BJ 08.32). I asked him why, and he answered: “because he has such a little head compared to his body, it implicates that if you do not read you will become stupid” (MA/BJ 10:25).

When asked how one could implicate that, he explained: “there is (only) room for a small brain inside, and a small brain figuratively means stupid” (MA/BJ 12:29).

A young woman in the same focus group added to this explanation that she read the message of the ad: “more as instead of watching television, because he is sitting there with the remote control” (MA11:55, my emphasis).

So, it is clear that the respondents actually decode an argument from the ad. And it is clear that the without the visuals the argument would not be constructed. Almost all respondents created the argument: “Read more, because if you don’t, you will become stupid”. Several, as we saw, added the circumstance: “Read more, instead of watching television”.

We should note as well that the formulations of the argument do not say that the person in the picture should read more. In general the respondents do not talk specifically about him, when reconstructing the argument. Instead they use general pronouns such as “one should read more”, or “you should read more”, They thus move from the specifics of the picture to a general level expressing a moral claim.

3. Pragmatic decoding

It is obvious that the respondents construct the term “stupid” from the visual representation of the little head. In general, it seems possible to visually evoke adjectives such as big, small, stupid, and the like. At the same time, we would probably be inclined to say, that images because of their lack of syntax and grammar are unable to evoke conjunctions that connect premises in an argument and create the necessary causal movements for an argument to be established. What does conjunctions such as “therefor”, “hence”, and “then” look like?

However, as we have seen, respondents do actually use conjunctions such as “then” and “therefor” both explicitly and implicitly. They also use formulations saying the visual elements “implicate” certain conclusions. Furthermore, the respondents explicitly mention the adversative conjunction “instead of”. Like the other conjunctions, the term “instead of”, and they way it is used to connect premises, is neither in the caption “read more”, nor represented anyway directly in the picture.

So, where do the conjunctions come from? In making sense of the three central elements in the ad – the caption “read more”, the little head, and the person’s sitting-position with the remote – a connection has to be made. In light of the advertising genre the most relevant and plausible connection would be argumentative conjunctions.

This kind of search for argumentative meaning is clear in several of the respondent’s interpretations. Take the pensioner, who said about the Steimatzky ad: “That you should read instead of watching television” (BR/UN 09:37). When I asked her to elaborate the woman said:

Well, if it is an advertisement for a bookstore, then they obviously want to give a message saying that he needs to read more, right? And then, where is the message in that picture? That’s got to mean that his head is so small, that he needs to fill up” (BR/UN, 09:37)

It is clear from this that she is not only searching to make sense of the ad by connecting verbal, visual, and contextual elements. She is also presupposing that the message has a persuasive character. Because of the imperative mood in the caption she immediately assumes that “read more” is the claim, and she naturally proceeds by looking for the reason. Her short elaboration illustrates two things.

Firstly, it illustrates that audiences are active in an exploring kind of mental labour while looking for the meaning and assumed argument in an image. This mental exploring is not incidental, but is generally performed in accordance with pragmatic rules of speech acts (Austin 1975, Searle 1969), relevance (Sperber & Wilson 1986), and implicature (Grice 1989); theories which we know have been successfully applied to the study of argumentation in for instance pragma-dialectics (e.g. Eemeren & Grootendorst 1983, Henkemans 2014). People obviously make implications, are consciously aware that the ads are trying to convey messages even arguments. And they clearly try to reconstruct these arguments.

Secondly, the example illustrates that much more is going on in the reception of this kind of visual argumentation, than can be expressed by stating only the premises and conclusion of the argument. The picture, so to speak, holds much more than the content of these short assertions.

4. Thickness and condensation

It is an important characteristic of predominantly visual argumentation that it allows for a symbolic condensation that prompts emotions and reasoning in the beholder. In the focus group of students, for instance, a young woman commented on the ad in this way:

if you do not read you will become a narrow-minded, potato-couch – non-thoughtful. He is not exactly sitting in a position, which is considered very flattering, intellectual, positive. The whole position is connected with a sick person” (MA/SI 11:34).

The basic argument: “Read more, because if you do not read you will become stupid” is clearly present in this comment, but the interpretation involves much more. Let me illustrate the significance of this visual surplus-meaning with a Norwegian ad for the tram-system in Oslo (see below, ill. 2). The ad shows a scene from the tram. The light blue box in the upper left has the same appearance as a ticket for the tam, however the text says: “Avoid embarrassing moments. Buy a ticket”. At the bottom of the ad the text says: “There are no excuses for dodging the fare (We are intensifying our controls)”.

Most respondents sum-med up the argument from this ad something like this: “Buy ticket, and you will avoid an unpleasant situation” (MV/MA 48:43). We could state the argument like this: “You should buy tickets, because it will make you avoid an unpleasant situation” However, if we reduce visual arguments to only these kind of context-less, thin premises, we also limit ourselves to putting forward only the skeleton of the rhetorical utterance instead of the full body. We reconstruct, in a sense, a lifeless argument.

In contrast to this, it quickly became obvious, when I interviewed people about the ads that much more was going on. We see that the stating of the premises and the reconstruction of the argument is embedded in a much thicker understanding of the depicted situation, and of similar situations and emotions evoked by the ad.

We discover that one of the benefits of visual or multimodal argumentation is that they provide what I call thick descriptions, a full sense of the situation, making an integrated, simultaneous appeal to both the emotional and the rational (cf. Kjeldsen 2012, 2013). One respondent said:

Well, they are obviously playing on the embarrassment of getting caught when not having a ticket. The way you shrink yourself when the inspector comes” (MV/BJ 48:43)

He later continued, saying: “You try to hide a little, you want to sink into the ground; because it is so embarrassing to get caught, you make yourself as little as possible.” (MV/BJ 48:43) Another respondent elaborated even more on what she felt the ad represented (MI/AN 31:15):

I am thinking that the person, the little man, has sneaked in. And when there is a ticket inspection, you always end up with those embarrassing situations, those looks, and you become embarrassed. Because it says, the text, “Avoid embarrassing moments. Buy tickets”. And then you would avoid being tense and get caught. And there are a lot of other people around that might think “Oh well, he got caught now”; and then you begin to think strange thoughts about the person that got caught.

The image clearly evokes imagined or previous experiences of embarrassment connected with sneaking on public transport. One person told that she herself had witnessed a “grown man” seemingly well enough off to pay the fare, but he still got caught without a ticket (MA/SI 48:43). Another vividly told about his fear and shame when he himself almost got caught without a ticket. All these descriptions and evoked emotions are, in fact, relevant parts of the argument. The more you feel the embarrassment, the more persuasive the argument will be. This, however, does not mean that the contribution of the image – or the ad as such – is just psychological and irrational persuasion.

It is true in this case, that the argument is more or less fully expressed by words in the text in the upper left corner, which says “Avoid embarrassing moments. Buy a ticket”. However, the premises created by these words alone, lack the full sense of situation and embarrassment experienced by the respondents, and expressed when they talk about the ad.

So, if we limit ourselves to reconstructions of the argument with short premise-conclusion assertions found only in textual analyses we will only get part of the argument expressed multimodally in the ad. Because the more I feel the embarrassment the more forceful the argument is, and the more correct the argument actually is; because the feeling of embarrassment is an important part of the argument. If you do not really feel the embarrassment, then you have not really understood the argument, since the good reason offered to buy a ticket is the possibility to avoid an unpleasant feeling. Of course one could attempt to express this in writing by saying something like: “You should buy a ticket, because it will make you avoid a very unpleasant situation”. However, adding modal modifiers to the premises does not truly capture the sense of embarrassment offered by the visual parts of the ad, and it is not likely to evoke the same kind of memories and full descriptions that the image clearly evoked in the respondents.

5. Conclusion

The point of the focus group analysis has neither to claim that the respondents’ interpretations are ”the correct interpretations”, nor to claim that other audiences will necessarily interpret the ads in the exact same way – even though this is what the focus group interviews clearly suggest. The point is simply to show that the ads invite the construction of a specific argument, and that the respondents generally made the preferred reading (cf. Hall 1993).

Much more could be said about the ads and reception analyses of visual argumentation. My studies of these and other ads, for instance, also suggest that the active interpretation of respondents evolves to an active form of arguing back, when images are seen to claim something in which the respondents disagree about. However, even though this has only been a very brief account of a small part of the focus group studies carried out, hopefully a few things has become clear:

Firstly, it is clear that audiences are cognitively involved in interpreting the meaning of pictures and multimodal utterances. In this rhetorical involvement audiences actively reconstruct arguments from pictures. They not only reconstruct the premises of an argument, but also the conjunctions that connect these premises.

Secondly, it is also clear that audiences can and do move argumentatively from the specific content in a picture to more general moral assertions.

Thirdly, the audiences’ reconstructions of the arguments as (thin) premises are generally embedded in a condensed, thick understanding of situations, experiences, and emotions that is invoked by the picture and influence the character and force of the argument.

So, where is visual argument? It is obviously present. It is found in argumentative situations, and we can locate it not only in images, but also in the minds of audiences. A place I believe we should into more frequently.

NOTES

[i] I have previously written about several of the pictures (including the Steimatzky-ad) shown to the respondents (cf. Kjeldsen 2012). This afforded the possibility to assess my previous interpretations of the visual argumentation in relation to the actual interpretation in the focus group situation.

[ii] This code marks the focus group (MI), the identity of respondent (AN), and the timeslot in the tape and the transcription for the utterance.

References

Ang, Ien. (1991). Desperately seeking the audience. New York: Routledge

Austin, J.L. (1973 [1962]). How to do things with words. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Black, E. 1998. The second persona. In (Eds.) Lucaites, J., Condit, C.M. Caudill, S. Contemporary Rhetorical Theory: A Reader (pp.331-340). New York: Guilford,.

Benoit, W.L. & Smythe, M.J. 2003. Rhetorical theory as message reception. A cognitive response approach to rhetorical theory and criticism. Communication Studies 54(1), 9-114.

Charland, M. (1987). Constitutive rhetoric: The case of the Peuple Québécois. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 73(2), 133–150.

Eemeren, F.V. & Grootendorst, R. (1983). Speech acts in argumentative discussions. Foris publications: Dordrecth.

Govier, T. (1999). The philosophy of Argument. Newport News, VA: Vale Press.

Grice, H.P. (1989 [1975]). Logic and conversation. In (Ed.) H.P. Grice Studies in the Way of Words (pp. 22–40). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Hall, S. (1993). Encoding/decoding. In (Ed.) S. During The Cultural Studies Reader. London and NY: Routledge.

Henkemans, A. F. S. 2014. Speech act theory and the study of argumentation. Studies in logic, grammar and rhetoric 36 (49), 41-58.

Johnson, R. (2013). The role of audience in argumentation from the perspective of informal logic. Philosophy and Rhetoric, 46 (4), 533-549

Kjeldsen, J.E. (2013). Virtues of visual argumentation. How pictures make the importance and strength of an argument salient. In (Eds.) Mohammed, D., & Lewiński, M. Virtues of Argumentation. Proceedings of the 10th International Conference of the Ontario Society for the Study of Argumentation (OSSA) (pp. 1-13) .22-26 May 2013. Windsor, ON: OSSA,

Kjeldsen, J.E. (2012). Pictorial argumentation in advertising: Visual tropes and figures as a way of creating visual argumentation. In (Eds.) F.H. van Eemeren, and B. Garssen Topical themes in argumentation theory. Twenty exploratory studies (pp. 239–255). Dordrecht: Springer.

Perelman, C. & L. Olbrechts-Tyteca. (1971 [1969/1958]). The new rhetoric. A treatise on argumentation. Paris: University of Notre Dame Press.

Schiappa, E. (2008). Beyond representational correctness. Rethinking criticism of popular media. Albany: State University Press.

Searle, J. (1969) Speech acts. An essay in the philosophy of language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wander, P. 2013. The third persona: An ideological turn in rhetorical theory, In (Eds) B.L. & G. Dickinson (red.), The Routledge Reader in Rhetorical Criticism (pp. 604–623). New York: Routledge,.

Wilson, D. & Sperber, D. (2012). Meaning and relevance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tindale, C. (2013). Rhetorical argumentation and the nature of audience: Toward an understanding of audience—Issues in argumentation. Philosophy and Rhetoric, 46 (4), 508-532.

Tindale, C. (1999). Acts of arguing: A rhetorical model of argument. Albany: SUNY Press.

Tindale, C. (1992). Audiences, relevance, and cognitive environments. Argumentation 6, 177-188.