Love Letters In A Networked Age

O, darling of mine, my God, how you make me happy! O, this letter, this letter from you, that I kiss and kiss…O, that you love me—that you love me too, and said so… O, bliss, o, bliss, that I am something in your life.

–Jeanne Reyneke van Stuwe to Willem Kloos, April 1899

I think I must have been the last person in the developed world still writing love letters. By 19th-century standards (see above), I don’t suppose they were very romantic. J. and I were children of a less gushy, more cynical age. We had already gone way beyond kissing each other’s letters, but felt we were being very daring—stepping over an invisible line of appropriate distance and refusal to hope—on the rare occasions when we wrote “I love you.”

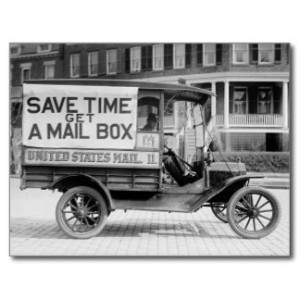

The point is, we wrote letters. Long ones, handwritten, with stamps. We kept track of last pickup times, ran downstairs when we heard the mail slot bang. We were patient: to send a letter and get its transatlantic answer took at least ten days. The phone, at a dollar a minute, was out of the question.

When one of J.’s letters came, I would carry it around with me for days. At quiet moments I would take it out, gaze at my own address written in his long-legged, beautiful hand, unfold the pages, and reread them. Sometimes J. sent me drawings or photos. Once he sent me flowers: he cut out, pasted onto paper, and mailed me the side of a milk carton with tulips on it. The day I lost one of J.’s illustrated postcards in the subway on my way home, I was as distraught as I would be now if my hard disk crashed.

If we had met now, and not 15 years ago, we wouldn’t be writing letters. We would be instant messaging, Skyping, taking out our iPhones to gaze at each other’s houses on Google Earth or Street View. We would e-mail links and photos, add each other’s local weather to our start page, friend each other on Facebook. We would exchange a lot of data.

We probably wouldn’t have missed letter-writing. Attachment to the letter as a physical object—isn’t that really just nostalgia? Writing letters is like listening to your old LPs: you like the way they look, you’re sentimental about their vinyl pop and scratch. But the music is the same.

Sometimes I wonder, though. J. and I are shy people. We felt safer on the page. In the digital world, would we still have gotten to know each other? Would it still have felt like a conversation?

The conversation on paper was, is, the magic of the letter. It’s why we write them, and it’s why we love to read other people’s. Later on, when I worked on a biography, I read folder after folder of my subject’s mail. Often it was like watching a passionate two-character play. The correspondents usually began as strangers and got to know each other over time. They gossiped, argued, made abrupt confessions, helped each other work out ideas, fell out, became friends.

A good letter-writer is a performer, playing a role for an audience of one. But performance can, paradoxically, lead to honesty, and distance enable greater frankness than a face-to-face talk. Belle van Zuylen, one of the all-time great literary flirts, wrote to Constant d’Hermenches in 1764, “I can’t speak to you the same way I can write to you. When I speak to you I see a man before me, a man with whom I have conversed no more than ten times in my life. It’s only natural that I should be thrown into confusion and not dare say certain words…”

We all know that feeling. Teenagers often have it; it’s one reason they would rather text each other than call. Could Belle van Zuylen still have flirted if she’d had a webcam? Would J. and I, through the static of Skype, still have told each other the truth about ourselves?

I miss the frankness of letters. But what I miss even more is the patience. Any letter, to anyone—I wrote a lot to friends in those days, too—took time. It had to be composed. You felt like you had to fill the paper down to the end; if you got to the bottom and weren’t quite done, you might continue along one side or add a note in the top margin. To achieve that feeling of a conversation, you had to think about what you wanted to say.

In his Atlantic article “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” technology journalist Nicholas Carr writes that since he started using the Internet, he has become so used to skipping from link to link that he has lost the knack of reading. “I get fidgety, lose the thread, begin looking for something else to do. I feel as if I’m always dragging my wayward brain back to the text.”

In the same way, I’ve lost the knack of letter-writing. I find myself skipping, not just from link to link, but from friend to friend. Many of my friendsare links, on a social networking site. I keep in touch with more people than ever, but superficially. Even e-mail often feels too time-consuming or too intimate. To write a long message is almost bad manners. It’s a breach of the most important rule of modern etiquette: don’t take up other people’s time.

Many people I know, including me, now communicate by posting notes for their entire social circle to read. The other day, I mentioned in an e-mail to a friend 3,000 miles away that a mutual acquaintance had had dinner at my house. He wrote back, “I know. I read it on her blog.”

Without the focus that the individual letter demands, we spread ourselves widely but thinly among our friends. If I miss the letter, it’s partly because I’m worried that, in the words of New York playwright Richard Foreman, we’re turning into “pancake people.”

I haven’t written a love letter in years. To say something to J. now, all I need to do is cross the room. But I don’t think I say as much to him now as I said then. We used to spend hours alone with each other – an ocean, two mail carriers, and 80 cents in stamps apart, joined by a piece of paper.

It was paper that gave us the courage to be something in each other’s lives.

Trouw, January 3, 2009. The two excerpts from love letters are from Nelleke Noordervliet, “Ik kan het niet langer verbergen: over liefdesbrieven” (Amsterdam: Meulenhoff, 1993). The translations are mine.

About the author:

Julie Phillips is a biographer, book critic, and essayist who moved from New York to Amsterdam to live with “J.” They recently celebrated their twentieth anniversary.

See: http://julie-phillips.com/wp/

James Tiptree, Jr.: The Double Life of Alice B. Sheldon:

http://www.amazon.com/James-Tiptree-Jr

Nicholas Carr: http://www.nicholascarr.com/