Why Culture Is Not The Only Tool For Defining Homo Sapiens In Relation To Other Hominins

Deborah Barsky

04-12-2004 ~ We need a broad comparative lens to produce useful explanations and narratives of our origins across time.

While the circumstances that led to the emergence of anatomically modern humans (AMH) remain a topic of debate, the species-centric idea that modern humans inevitably came to dominate the world because they were culturally and behaviorally superior to other hominins is still largely accepted. The global spread of Homo sapiens was often hypothesized to have taken place as a rapid takeover linked mainly to two factors: technological supremacy and unmatched complex symbolic communication. These factors combined to define the concept of “modern behavior” that was initially allocated exclusively to H. sapiens.

Up until the 1990s, and even into the early 21st century, many assumed that the demographic success experienced by H. sapiens was consequential to these two distinctive attributes. As a result, humans “behaving in a modern way” experienced unprecedented demographic success, spreading out of their African homeland and “colonizing” Europe and Asia. Following this, interpopulation contacts multiplied, operating as a stimulus for a cumulative culture that climaxed in the impressive technological and artistic feats, which defined the European Upper Paleolithic. Establishing a link between increased population density and greater innovation offered an explanation for how H. sapiens replaced the Neandertals in Eurasia and achieved superiority to become the last survivor of the genus Homo.

The exodus of modern humans from Africa was often depicted by a map of the Old World showing an arrow pointing northward out of the African continent and then splitting into two smaller arrows: one directed toward the west, into Europe, and the other toward the east, into Asia. As the story goes, AMHs continued their progression thanks to their advanced technological and cerebral capacities (and their presumed thirst for exploration), eventually reaching the Americas by way of land bridges exposed toward the end of the last major glacial event, sometime after 20,000 years ago. Curiosity and innovation were put forward as the faculties that would eventually allow them to master seafaring, and to occupy even the most isolated territories of Oceania.

It was proposed that early modern humans took the most likely land route out of Africa through the Levantine corridor, eventually encountering and “replacing” the Neandertal peoples that had been thriving in these lands over many millennia. There has been much debate about the dating of this event and whether it took place in multiple phases (or waves) or as a single episode. The timing of the incursion of H. sapiens into Western Europe was estimated at around 40,000 years ago; a period roughly concurrent with the disappearance of the Neandertal peoples.

This scenario also matched the chrono-cultural sequence for the European Upper Paleolithic as that was defined since the late 19th century from eponymous French archeological sites, namely: Aurignacian (from Aurignac), Gravettian (from La Gravette), Solutrean (from Solutré), and Magdalenian(from la Madeleine). Taking advantage of the stratigraphic sequences provided by these key sites that contained rich artifact records, prehistorians chronicled and defined the typological features that still serve to distinguish each of the Upper Paleolithic cultures. Progressively acknowledged as a reality attributed to modern humans, this evolutionary sequencing was extrapolated over much of Eurasia, where it fits more or less snugly with the archeological realities of each region.

Each of these cultural complexes denotes a geographically and chronologically constrained cultural unit that is formally defined by a specific set of artifacts (tools, structures, art, etc.). In turn, these remnants provide us with information about the behaviors and lifestyles of the peoples that made and used them. The Aurignacian cultural complex that appeared approximately 40,000 years ago (presumably in Eastern Europe) heralded the beginning of the Upper Paleolithic period that ended with the disappearance of the last Magdalenian peoples some 30,000 years later—at the beginning of the interglacial phase marking the onset of the (actual) Holocene epoch.

The conditions under which the transition from the Middle to the Upper Paleolithic took place in Eurasia remains a topic of hot debate. Some argue that the chronological situation and features of Châtelperronian toolkits identified in parts of France and Spain and the Uluzzian culture in Italy, should be considered intermediate between the Middle and Upper Paleolithic, while for others, it remains unclear whether Neandertals or modern humans were the authors of these assemblages. This is not unusual, since the thresholds separating the most significant phases marking cultural change in the nearly 3 million-year-long Paleolithic record are mostly invisible in the archeological register, where time has masked the subtleties of their nature, making them seem to appear abruptly. Read more

Armenia’s Escape From Isolation Lies Through Georgia

John P. Ruehl Independent Media Institute

04-11-2024 ~ Surrounded to its east and west by hostile neighbors and devoid of allies, Armenia’s geopolitical situation faces severe challenges. A growing partnership with Georgia could help the small, landlocked country to expand its options.

For the second time this year, Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan met with his Georgian counterpart on March 24. The meeting, held in Armenia’s capital of Yerevan, saw both leaders reaffirming their growing commitment to enhancing already positive relations. Armenia has placed greater emphasis on recognizing the untapped potential of Georgia in recent years, given Yerevan’s increasingly challenging geopolitical circumstances.

Armenia underwent a significant foreign policy shift away from Russia and towards Europe following the 2018 Velvet Revolution and the election of Pashinyan. However, this shift exposed the country’s security vulnerabilities. In 2020, neighboring Azerbaijan decisively defeated Armenian forces defending the Armenian-majority enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh in 2020, followed by subsequent clashes in 2022 and 2023, leading to the dissolution of the enclave. With its current military advantage, Azerbaijan’s forces are instigating border confrontations on Armenian territory and demanding the return of several small Azerbaijani villages in Armenia.

Azerbaijan has refused to participate in EU or U.S.-initiated peace talks in recent months. Meanwhile, Russia has largely ignored Armenia’s plight amid its struggles in Ukraine to punish Yerevan. Instead, Russia has sought closer ties with Azerbaijan, as evidenced by Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev’s visit to Moscow immediately after Russia recognized the independence of the Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics in Ukraine. During the 2022 visit, pledges were made to increase military and diplomatic cooperation between Russia and Azerbaijan and to resolve remaining border issues.

Russia maintains a military base in Armenia, controls parts of its border, and wields significant economic influence in the country. Despite this, Armenia opposes Moscow’s mediation in peace talks and continues to seek closer ties to the West. While Western countries have shown sympathy to Armenia’s plight and criticized Azerbaijan, Armenia has received little tangible assistance. Azerbaijan’s emergence as a vital transport corridor and source of natural resources, combined with the limited ability of the West to project power in the Caucasus region, has prevented the West from taking harsher measures against it.

The small American military force sent for a joint military exercise with Armenia, for example, concluded on the day of the 2023 war which marked the end of Nagorno-Karabakh’s existence. Despite its presence, the force was powerless to dissuade Azerbaijan. Additionally, while U.S. President Joe Biden initially declared his intention to withhold U.S. military aid to Azerbaijan due to its actions against Armenia in 2020, he later reversed this decision—a pattern consistent with previous U.S. administrations since the early 1990s. The decision is currently pending ratification despite domestic opposition in the U.S. Read more

The Myth That India’s Freedom Was Won Nonviolently Is Holding Back Progress

Justin Podur – Source: York University – podur.org

04-10-2024 ~ Some struggles can be kept nonviolent, but decolonization never has been—certainly not in India.

If there is a single false claim to “nonviolent” struggle that has most powerfully captured the imagination of the world, it is the claim that India, under Gandhi’s leadership, defeated the mighty British Empire and won her independence through the nonviolent method.

India’s independence struggle was a process replete with violence. The nonviolent myth was imposed afterward. It is time to get back to reality. Using recent works on the role of violence in the Indian freedom struggle, it’s possible to compile a chronology of the independence movement in which armed struggle played a decisive role. Some of these sources: Palagummi Sainath’s The Last Heroes, Kama Maclean’s A Revolutionary History of Interwar India, Durba Ghosh’s Gentlemanly Terrorists, Pramod Kapoor’s 1946 Royal Indian Navy Mutiny: Last War of Independence, Vijay Prashad’s edited book, The 1921 Uprising in Malabar, and Anita Anand’s The Patient Assassin.

Nonviolence could never defeat a colonial power that had conquered the subcontinent through nearly unimaginable levels of violence. India was conquered step by step by the British East India Company in a series of wars. While the British East India Company had incorporated in 1599, the tide turned against India’s independence in 1757 at the battle of Plassey. A century of encroaching Company rule followed—covered in William Dalrymple’s book The Anarchy—with Company policy and enforced famines murdering tens of millions of people.

In 1857, Indian soldiers working for the Company rose up with some of the few remaining independent Indian rulers who had not yet been dispossessed—to try to oust the British. In response, the British murdered an estimated (by Amaresh Mishra, in the book War of Civilisations) 10 million people.

The British government took over from the Company and proceeded to rule India directly for another 90 years.

From 1757 to 1947, in addition to the ten million killed in the 1857 war alone, another 30-plus million were killed in enforced famines, per figures presented by Indian politician Shashi Tharoor in the 2016 book Inglorious Empire: What the British Did to India.

A 2022 study estimated another 100 million excess deaths in India due to British imperialism from 1880 to 1920 alone. Doctors like Mubin Syed believe that these famines were so great and over such a long period of time that they exerted selective pressure on the genes of South Asian populations, increasing their risk of diabetes, heart disease, and other diseases that arise when abundant calories are available because South Asian bodies have become famine-adapted.

By the end, the independence struggle against the British included all of the methods characteristic of armed struggle: clandestine organization, punishment of collaborators, assassinations, sabotage, attacks on police stations, military mutinies, and even the development of autonomous zones and a parallel government apparatus.

A Chronology of India’s Violent Independence Struggle

In his 2006 article, “India, Armed Struggle in the Independence Movement,” scholar Kunal Chattopadhyay broke the struggle down into a series of phases:

1905-1911: Revolutionary Terrorism. A period of “revolutionary terrorism” started with the assassination of a British official of the Bombay presidency in 1897 by Damodar and Balkrishna Chapekar, who were both hanged. From 1905 to 1907, independence fighters (deemed “terrorists” by the British) attacked railway ticket offices, post offices, and banks, and threw bombs, all to fight the partition of Bengal in 1905. In 1908, Khudiram Bose was executed by the imperialists for “terrorism.”

These “terrorists” of Bengal were a source of great worry to the British. In 1911, the British repealed the partition of Bengal, removing the main grievance of the terrorists. They also passed the Criminal Tribes Act, combining their anxieties over their continued rule with their ever-present racial anxieties. The Home Secretary of the Government of India is quoted in Durba Ghosh’s book Gentlemanly Terrorists:

“There is a serious risk, unless the movement in Bengal is checked, that political dacoits and professional dacoits in other provinces may join hands and that the bad example set by these men in an unwarlike province like Bengal may, if it continues, lead to imitation in provinces inhabited by fighting races where the results would be even more disastrous.” Read more

Big Oil Ignores Millions Of Climate Deaths When Billions In Profit Are At Stake

C.J. Polychroniou

04-08-2024 ~ As the world burns, radical climate change activism is our only hope.

Human activity in a profit-driven world divided by nation-states and those who have rights and those who don’t is the primary driver of climate change. Burning fossil fuels and destroying forests have caused inestimable environmental harm by producing a warming effect through the artificial concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Carbon dioxide (CO2) has risen by 50 percent in the past 200 years, much of it since the 1970s, raising in turn the Earth’s temperature by roughly 2 degrees Fahrenheit.

Indeed, since the 1970s, the decade which saw the rise of neoliberalism as the dominant economic ideology in the Western world, CO2 emissions have increased by about 90 percent. Unsurprisingly, average temperatures have risen more quickly over the past few decades, and the last 10 years have been the warmest years on record. In fact, a National Aeronautics and Space Administration analysis has confirmed that 2023 was the warmest year on record, and all indications are that 2024 could be even hotter than 2023. In March, scientists at Copernicus Climate Change Service said that February 2024 was the hottest February, according to records going back to 1940.

The world is now warming faster than any point in recorded history. Yet, while the science of climate change is well established and we know both the causes and the effects of global warming, the rulers of the world are showing no signs of discontinuing their destructive activities that are putting Earth on track to becoming uninhabitable for humans. Emissions from Russia’s war in Ukraine and Israel’s utter destruction of Gaza will undoubtedly have a significant effect on climate change. Analysis by researchers in the United Kingdom and United States reveals that the majority of global emissions generated in the first two months of the Israeli invasion of Gaza can be attributed to the aerial bombardment of the Gaza Strip. Indeed, the destruction of Gaza is so immense that it exceeds, proportionally, the Allied bombing of Germany in World War II.

Further evidence that the rulers of the world view themselves as being separate and distinct from the world around them (in spite of the fact that all life on Earth is at risk) came during the recent CERAWeek oil summit in Houston, Texas, where executives from the world’s leading fossil fuel companies said that we should “abandon the fantasy of phasing out oil and gas.” Who from the likes of ExxonMobil, Chevron, Shell, BP and TotalEnergies gives a damn if the emissions from the burning of fossil fuels until 2050 causes millions of deaths before the end of the century? Oil and gas companies made tens of billions in annual net profit in 2023 as they continued to expand fossil fuel production.

Of course, none of the above is to suggest that the game is over. The rulers of the world (powerful states, huge corporations, and the financial elite) are always pulling out all the stops to resist change and maintain the status quo. But common people are fighting back, and history has repeatedly shown that they will never surrender to the forces of reaction and oppression. We have seen a remarkable escalation of climate and political activism in general over the past several years — indeed, a sharp awakening of global public consciousness to the interconnectedness of challenges in the 21st century that leaves much room for hope about the future. Struggles against climate change are connected to the fight against imperialism, inequality, poverty and injustice. These struggles are not in vain, even when the odds seem stacked against them. On the contrary, they have produced some remarkable results.

Deforestation in Brazil’s Amazon rainforest is falling dramatically since President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva came into office — a victory not only for the Brazilian people but for those across the world who care about the environment and justice. In North America, Indigenous communities scored major victories in 2023 in the struggle for conservation, protecting hundreds of thousands of acres of forest land and sacred and culturally significant sites from mining. Climate activists in Europe and the U.S. won major legal victories throughout 2023, such as the youth victory against the state of Montana. Similar climate litigation like Juliana v. United States is only expected to grow in 2024. As actor and climate activist Jane Fonda aptly put it on “Fire Drill Fridays,” a video program that was launched in 2019 by Fonda herself in collaboration with Greenpeace USA, “These lawsuits are not just legal maneuvers … but are at the crux of climate reckoning.”

These victories for our planet are more than enough proof that activism pays off and should be an acute reminder that the kind of transformational change we need will not start at the top. In 2018, the climate protest of a 15-year-old Swedish student captured the imagination of her own country and eventually “aroused the world,” to use the words of British broadcaster and naturalist Sir David Attenborough. Indeed, just a year later, Greta Thunberg would be credited with leading the biggest climate protest in history.

It is grassroots environmental activism that created the political space for President Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act — the largest investment in clean energy and climate action in U.S. history. (It’s important to point out that the law stripped out many social and economic programs in the original draft that are critical for low-income communities and communities of color, and the law lacks a deep decarbonization pathway.) Environmental movements such as Fridays for Future, Extinction Rebellion, Just Stop Oil, and Letzte Generation have sparked a global conversation on the climate crisis and have opened up new possibilities for forcing the transition away from fossil fuels across Europe even in the face of a growing backlash by hard-line conservative and far right groups, and even as European governments crack down on climate protests.

The rulers of the world won’t save the planet. They have a vested interest in maintaining the existing state of affairs, whether it be oppression of the weak or continued reliance on fossil fuels. Radical political action is our only hope because voting alone will never solve our problems. Organizing communities, raising awareness and educating the public, and developing convincing accounts of change are key elements for creating real progress in politics. Indeed, as the recent history of environmental politics shows, climate activism is the pathway to climate defense.

Copyright © Truthout. May not be reprinted without permission.

C.J. Polychroniou is a political scientist/political economist, author, and journalist who has taught and worked in numerous universities and research centers in Europe and the United States. Currently, his main research interests are in U.S. politics and the political economy of the United States, European economic integration, globalization, climate change and environmental economics, and the deconstruction of neoliberalism’s politico-economic project. He is a regular contributor to Truthout as well as a member of Truthout’s Public Intellectual Project. He has published scores of books and over 1,000 articles which have appeared in a variety of journals, magazines, newspapers and popular news websites. Many of his publications have been translated into a multitude of different languages, including Arabic, Chinese, Croatian, Dutch, French, German, Greek, Italian, Japanese, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish and Turkish. His latest books are Optimism Over Despair: Noam Chomsky On Capitalism, Empire, and Social Change (2017); Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet (with Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin as primary authors, 2020); The Precipice: Neoliberalism, the Pandemic, and the Urgent Need for Radical Change (an anthology of interviews with Noam Chomsky, 2021); and Economics and the Left: Interviews with Progressive Economists (2021).

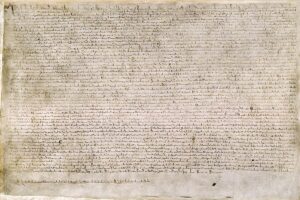

How Elite Infighting Made The Magna Carta

Magna Carta Libertatum 1215 – British Library

04-06-2024 ~ Although the Magna Carta typically is depicted as the birth of England’s fight to create democracy, the 13th-century struggle was to establish what would become the House of Lords, not the House of Commons.

The papacy’s role as organizer of the Crusades empowered it to ask for—indeed, to demand—tithes from churches and royal tax assessments from realms ruled by the warlord dynasties it had installed and protected. England’s nobility and clergy pressed for parliamentary reform to block King John and his son Edward III from submitting to Rome’s demands to take on debts to finance its crusading and fights against Germany’s kings. Popes responded by excommunicating reformers and nullifying the Magna Carta again and again during the 13th century.

The Burdensome Reign of King John

John I (1199-1216) was dubbed “Lackland” because, as Henry II’s fourth and youngest son, he was not expected to inherit any land. On becoming his father’s favorite, he was assigned land in Ireland and France, which led to ongoing warfare after his brother Richard I died in 1199. This conflict was financed by loans that John paid by raising taxes on England’s barons, churches, and monasteries. John fought the French for land in 1202, but lost Normandy in 1204. He prepared for renewed war in France by imposing a tallage in 1207; as S.K. Mitchell details in his book on the subject, this was the first such tax for a purpose other than a crusade.

By the 13th century, royal taxes to pay debts were becoming regular, while the papacy made regular demands on European churches for tithes to pay for the Crusades. These levies created rising opposition throughout Christendom, from churches as well as the baronage and the population at large. In 1210, when John imposed an even steeper tallage, many landholders were forced into debt.

John opened a political war on two fronts by insisting on his power of investiture to appoint bishops. When the Archbishop of Canterbury died in 1205, the king sought to appoint his successor. Innocent III consecrated Stephen Langdon as his own candidate, but John barred Stephen from landing in England and started confiscating papal estates. In 1211 the pope sent his envoy, Pandulf Verraccio, to threaten John with excommunication. John backed down and allowed Stephen to take his position, but then collected an estimated 14 percent of church income for his royal budget over the next two years—£100,000, including Peter’s Pence.

Innocent sent Pandulf back to England in May 1213 to insist that John reimburse Rome for the revenue that he had withheld. John capitulated at a ceremony at the Templar church at Dover and reaffirmed the royal tradition of fealty to the pope. As William Lunt details in Financial Relations of the Papacy with England to 1327, John received England and Ireland back in his fiefdom by promising to render one thousand marks annually to Rome over and above the payment of Peter’s Pence, and permitted the pope to deal directly with the principal local collectors without royal intervention.

John soon stopped payments, but Innocent didn’t protest, satisfied with having reinforced the principle of papal rights over his vassal king. In 1220, however, the new pope “Honorius III instructed Pandulf to send the proceeds of the [tallage of a] twentieth, the census [penny poll tax] and Peter’s Pence to Paris for deposit with the Templars and Hospitallers.”[1] Royal control of church revenue was lost for good. The contributions that earlier Norman kings had sent to Rome were treated as having set a precedent that the papacy refused to relinquish. The clergy itself balked at complying with papal demands, and churches paid no more in 1273 than they had in 1192.

The barons were less able to engage in such resistance. Historian David Carpenter calculates that their indebtedness to John for unpaid taxes, tallages, and fines rose by 380 percent from 1199 to 1208. And John became notorious for imposing fines on barons who opposed him. That caused rising opposition from landholders—the fight that Richard had sought to avoid. The Exchequer’s records enabled John to find the individuals who owed money and to use royal fiscal claims as a political lever, by either calling in the debts or agreeing to “postpone or pardon them as a form of favor” for barons who did not oppose him.

John’s most unpopular imposition was the scutage fee for knights to buy exemption from military service. Even when there was no actual war, John levied scutage charges eleven times during his 17-year reign, forcing many knights into debt. Rising hostility to John’s campaign in 1214 to reconquer his former holdings in Normandy triggered the First Barons’ War (1215-1217) demanding the Magna Carta in 1215.

Opposition was strongest in the north of England, where barons owed heavy tax debts. As described in J.C. Holt’s classic study The Northeners, they led a march on London, assembling on the banks of the Thames at Runnymede on June 15, 1215. Although the Archbishop of Canterbury, Stephen Langdon, helped negotiate a truce based on a “charter of liberties,” a plan for reform between John and the barons that became the Magna Carta, the “rebellion of the king’s debtors” led to a decade-long fight, with the Magna Carta being given its final version under the teenaged Henry III in 1225.

Proto-Democratic Elements of the Magna Carta

There were proto-democratic elements in the Charter, most significantly the attempt to limit the king’s authority to levy taxes without the consent of a committee selected by the barons. The concept of “no taxation without representation” appears in the original Chapter 12: “No scutage or aid is to be levied in our kingdom, save by the common counsel of our kingdom,” and even then, only to ransom the king or for specified family occasions.

The linkage between debt, interest accruals, and land tenure was central to the Charter. Chapter 9 stated that debts should be paid out of movable property (chattels), not land. “Neither we [the king] nor our bailiffs are to seize any land or rent for any debt, for as long as the chattels of the debtor suffice to pay the debt.” Land would be forfeited only as a last resort, when sureties had their own lands threatened with foreclosure. And under the initial version of the Charter, debts were only to be paid after appropriate living expenses had been met, and no interest would accrue until the debtor’s heirs reached maturity.

Elite Interests in the Charter

The Magna Carta typically is depicted as the birth of England’s fight to create democracy. It was indeed an attempt to establish parliamentary restraint on royal spending, but the barons were acting strictly in their own interest. The Charter dealt with breaches by the king, but “no procedure was laid down for dealing with breaches by the barons.” In Chapter 39 they designated themselves as Freemen, meaning anyone who owned land, but that excluded rural villeins and cottagers. Local administration remained corrupt, and the Charter had no provisions to prevent lords from exploiting their sub-tenants, who had no voice in consenting to royal demands for scutages or other aids.

The 13th-century fight was to establish what would become the House of Lords, not the House of Commons. Empowering the nobility against the state was the opposite of the 19th-century drive against the landlord class and its claims for hereditary land rent. What was deemed democratic in Britain’s 1909/10 constitutional crisis was the ruling that the Lords never again could reject a House of Commons revenue act. The Commons had passed a land tax, which the House of Lords blocked. That fight against landlords was the opposite of the barons’ fight against King John.

Note:

1. William Lunt, “Financial Relations of the Papacy with England to 1327. (Studies in Anglo-Papal Relations during the Middle Ages, I.),” (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Mediaeval Academy of America, 1939) pp. 597-598 and pp. 58-59.

By Michael Hudson

Author Bio:

Michael Hudson is an American economist, a professor of economics at the University of Missouri–Kansas City, and a researcher at the Levy Economics Institute at Bard College. He is a former Wall Street analyst, political consultant, commentator, and journalist. You can read more of Hudson’s economic history on the Observatory.

Source: Human Bridges

Credit Line: This article was produced by Human Bridges.

The Unremarkable Death Of Migrants In The Sahara Desert

Vijay Prashad

04-06-2024 ~ Sabah, Libya, is an oasis town at the northern edge of the Sahara Desert. To stand at the edge of the town and look southward into the desert toward Niger is forbidding. The sand stretches past infinity, and if there is a wind, it lifts the sand to cover the sky. Cars come down the road past the al-Baraka Mosque into the town. Some of these cars come from Algeria (although the border is often closed) or from Djebel al-Akakus, the mountains that run along the western edge of Libya. Occasionally, a white Toyota truck filled with men from the Sahel region of Africa and from western Africa makes its way into Sabah. Miraculously, these men have made it across the desert, which is why many of them clamber out of their truck and fall to the ground in desperate prayer. Sabah means “morning” or “promise” in Arabic, which is a fitting word for this town that grips the edge of the massive, growing, and dangerous Sahara.

For the past decade, the United Nations International Organization of Migration (IOM) has collected data on the deaths of migrants. This Missing Migrants Project publishes its numbers each year, and so this April, it has released its latest figures. For the past ten years, the IOM says that 64,371 women, men, and children have died while on the move (half of them have died in the Mediterranean Sea). On average, each year since 2014, 4,000 people have died. However, in 2023, the number rose to 8,000. One in three migrants who flee a conflict zone die on the way to safety. These numbers, however, are grossly deflated, since the IOM simply cannot keep track of what they call “irregular migration.” For instance, the IOM admits, “[S]ome experts believe that more migrants die while crossing the Sahara Desert than in the Mediterranean Sea.”

Sandstorms and Gunmen

Abdel Salam, who runs a small business in the town, pointed out into the distance and said, “In that direction is Toummo,” the Libyan border town with Niger. He sweeps his hands across the landscape and says that in the region between Niger and Algeria is the Salvador Pass, and it is through that gap that drugs, migrants, and weapons move back and forth, a trade that enriches many of the small towns in the area, such as Ubari. With the erosion of the Libyan state since the NATO war in 2011, the border is largely porous and dangerous. It was from here that the al-Qaeda leader Mokhtar Belmokhtar moved his troops from northern Mali into the Fezzan region of Libya in 2013 (he was said to have been killed in Libya in 2015). It is also the area dominated by the al-Qaeda cigarette smugglers, who cart millions of Albanian-made Cleopatra cigarettes across the Sahara into the Sahel (Belmokhtar, for instance, was known as the “Marlboro Man” for his role in this trade). An occasional Toyota truck makes its way toward the city. But many of them vanish into the desert, a victim of the terrifying sandstorms or of kidnappers and thieves. No one can keep track of these disappearances, since no one even knows that they have happened.

Matteo Garrone’s Oscar-nominated Io Capitano (2023) tells the story of two Senegalese boys—Seydou and Moussa—who go from Senegal to Italy through Mali, Niger, and then Libya, where they are incarcerated before they flee across the Mediterranean to Italy in an old boat. Garrone built the story around the accounts of several migrants, including Kouassi Pli Adama Mamadou (from Côte d’Ivoire, now an activist who lives in Caserta, Italy). The film does not shy away from the harsh beauty of the Sahara, which claims the lives of migrants who are not yet seen as migrants by Europe. The focus of the film is on the journey to Europe, although most Africans migrate within the continent (21 million Africans live in countries in which they were not born). Io Capitano ends with a helicopter flying above the ship as it nears the Italian coastline; it has already been pointed out that the film does not acknowledge racist policies that will greet Seydou and Moussa. What is not shown in the film is how European countries have tried to build a fortress in the Sahel region to prevent migration northwards.

Open-Air Tomb

More and more migrants have sought the Niger-Libya route after the fall of the Libyan state in 2011 and the crackdown on the Moroccan-Spanish border at Melilla and Ceuta. A decade ago, the European states turned their attention to this route, trying to build a European “wall” in the Sahara against the migrants. The point was to stop the migrants before they get to the Mediterranean Sea, where they become an embarrassment to Europe. France, leading the way, brought together five of the Sahel states (Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger) in 2014 to create the G5 Sahel. In 2015, under French pressure, the government of Niger passed Law 2015-36 that criminalized migration through the country. G5 Sahel and the law in Niger came alongside European Union funding to provide surveillance technologies—illegal in Europe—to be used in this band of countries against migrants. In 2016, the United States built the world’s largest drone base in Agadez, Niger, as part of this anti-migrant program. In May 2023, Border Forensics studied the paths of the migrants and found that due to the law in Niger and these other mechanisms the Sahara had become an “open-air tomb.”

Over the past few years, however, all of this has begun to unravel. The coup d’états in Guinea (2021), Mali (2021), Burkina Faso (2022), and Niger (2023) have resulted in the dismantling of G5 Sahel as well as the demand for the removal of French and U.S. troops. In November 2023, the government of Niger revoked Law 2015-36 and freed those who had been accused of being smugglers.

Abdourahamane, a local grandee, stood beside the Grand Mosque in Agadez and talked about the migrants. “The people who come here are our brothers and sisters,” he said. “They come. They rest. They leave. They do not bring us problems.” The mosque, built of clay, bears within it the marks of the desert, but it is not transient. Abdourahamane told me that it goes back to the 16th century, long before modern Europe was born. Many of the migrants come here to get their blessings before they buy sunglasses and head across the desert, hoping that they make it through the sands and find their destiny somewhere across the horizon.

By Vijay Prashad

Author Bio: This article was produced by Globetrotter.

Vijay Prashad is an Indian historian, editor, and journalist. He is a writing fellow and chief correspondent at Globetrotter. He is an editor of LeftWord Books and the director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. He has written more than 20 books, including The Darker Nations and The Poorer Nations. His latest books are Struggle Makes Us Human: Learning from Movements for Socialism and (with Noam Chomsky) The Withdrawal: Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan, and the Fragility of U.S. Power.

Source: Globetrotter