Three Secular Seductions: One nation, One government, One science ~ Festschrift for Dr. Sytse Strijbos

Introduction

Introduction

Is evidence-based politics [i] an idea a monolithic view of society? In one version of such a monolithic view, it is (a) the government that directs a society within (b) the boundaries of a nation-state, giving much credit to (c) the ‘oracles’ of science in the process to take its policy decisions.

In this essay I try to clarify why this monolithic view of society is dangerously flawed. Part of the reasoning below will be a description of

1) pluralities that are real, but obscured within a seemingly monolithic view of a government, a nation-state and/or science.

2) a religious or pseudo-religious status that willingly or unwillingly can be assigned to (a) the role of a government, (b) a nation-state and its boundaries; and/or (c) an evidence-based approach of political decision-making. The focus of this essay will be on the latter (c), which usually implicates an appeal to science. However, from the outset it must be clear that this essay is not a plea for fact free politics. On the contrary, the careful, methodical or scientific, academically embedded search for relevant information is recognized as an asset. Dangerous effects of the evidence-based approach are related to the supposed status of the academic expert and its possible anti-democratic or other restrictive effects.

Although applicable within the wider context of North-Atlantic (‘Western’) culture, Sytse Strijbos’ homeland, the Netherlands, is the assumed political context for the contentions that follow. Specifically, at the end of this essay (section 6.2) I will refer to a recent report published – in Dutch – by the Council for Public Health and Society in the Netherlands. In this report the approach of evidence-based practices in health care is criticized and at least relativized. This report is important because the government – every government – has a responsibility for public health and its funding.

Disclosive Systems Thinking, to which the name of Sytse Strijbos adheres firmly, represents an interdisciplinary and pluralistic, multi-aspectual approach to societal issues. Because of its pluralistic nature it provides several clues to dissect monolithic views. Specific philosophical sources fuelled this pluralistic look and feel of Disclosive Systems Thinking. These sources will be used to guide this dissection of ‘one nation, one government, one science’ into its constituents and to understand clashes both between these three domains and within each of them. These clashes can be multicultural tensions, parliamentary debates or deadlocks, or scientists disagreeing because of conflicting paradigms. The selection of these three seductive domains out of many more domains (money, music, drugs, …) is guided by the current popularity of evidence-based politics [ii] and its context: ‘evidence’ is expected from science; ‘politics’ is expected from the government; and a national government, to which I restrict myself here, assumes a nation state as context for its policies.

In the title ‘Three secular seductions’ the term ‘secular’ deserves clarification. I use ‘secular’ in the general (unreflected [iii]) sense of ‘this-worldly’, not ‘otherworldly’. In the title, and in writing for example about ‘oracles’ of science, I deliberately mix religious or moral terms like ‘oracles’ or ‘seductions’ with phaenomena usually considered as belonging to this world, this saeculum: nations, governments, sciences. So to these domains or phaenomena the adjective ‘secular’ is attached, not necessarily to the people dealing with them. On the contrary, I don’t consider religious people – here: people acknowledging some otherworldly influence – to be more immune to the seductive effects of an undivided, impressive nation, a strong government or the supposed objectivity of science than other people who would call themselves secular. Nor do I consider secular people more immune to these seductions than people who would call themselves religious.

My point is: these immanent, this-worldly, phaenomena can have similar effects that usually are ascribed to supposedly otherworldly or transcendent phaenomena. Examples of these effects are: producing energetic zeal, putting a devotee under a spell, untying strong loyalty or absolute trust, or demanding absolute obedience or unconditional acceptance of verdicts. These effects can lead to both positive and negative behaviour. Usually these effects are associated with religious people. For people living comfortably in ‘a secular age’ with its generally presupposed ‘immanent frame’ (Charles Taylor) it is more likely that supposedly secular phaenomena are triggering these effects than overtly supposedly otherworldly ones. Writing about nationalism below, I appeal to the late Lancaster professor of Religious Studies, Ninian Smart, to defend such a blended treatment of religions, worldviews and some encompassing -isms.

After introducing several types of plurality, this essay provides a closer look at the three domains of nation-state, government and science, in order to bring to light inherent pluralities within each of them. These pluralities are easily ignored by types of nationalism or patriotism, by centralistic views of governance, and by types of scientism. The essay converges into a plea for these pluralities to be explicitly acknowledged within society and government, in order to prevent oppressive styles of politics.

A plurality of pluralities

One of Strijbos’ prominent academic concerns has been to promote an interdisciplinary approach to theoretical reflection, especially to reflection directed towards practices in society. Not only he ‘fathered’ the Centre for Philosophy, Technology and Social Systems, but from 1996-2012 he was one of the driving forces for the annual working conferences of this CPTS. Looking back on the 9th one, Spring 2003, he wrote a discussion paper: ‘Towards a new interdisciplinarity’ in which he wrote: “It is the main objective of the CPTS to create a kind of interdisciplinarity which enables to address the broader societal issues in the research process and the design stage of technology”.[iv]

Systems theoreticist Gerald Midgley considers as one of the ‘significant strengths’ of this interdisciplinary approach that it ‘is inclusive of ethical debates’, for example by dialogue during the design stage of new technologies. However, he fears that in real life during these dialogues ethicists will be ‘captured’ by ‘scientists with a nascent technology, employed by a company’. Does anyone know of a technology under development, that has been abandoned ‘after hearing the arguments of philosophers’? He seems to prefer another option for ethicists, that is the option, ‘through alliances with other stakeholders, to make their case in various civil society fora’.[v]

A key term in interdisciplinarity is plurality. However, the previous two paragraphs make clear that not only a plurality of academic disciplines is relevant for the type of systems thinking Strijbos advocates. There is a plurality of practices in society, too (practices broadly taken). Among these practices ‘doing science’ and ‘doing technology’ themselves already are two, and, if you want, ‘doing philosophy’ another. Other societal practices are focussed on economy (business, banks, factories), politics (in formal or informal ways), art (orchestras, musea) or spiritualties (churches, mosques); on family life, education (primary schools, high schools), social life or leisure (clubs) or whatever.

Another type pf plurality is pointed to by Midgley writing on (the lack of) fora for ‘ethical debate’. When and where interpretative steps or normative issues are involved, human beings often appear to approach these issues from differing perspectives, as if they arrive at the issue from differing directions. It is one thing to signal global climate change (and even that is not without interpretation debates!), it’s another thing how to react to it: which and whose behaviour has to be restricted, and to what extent, if any behaviour at all? Exactly these different perspectives explain the lengthy political debates in parliament or in the press.

Yet another type of plurality is not yet mentioned. Although the CPTS working conferences were organised in the Netherlands, participants came from Sweden and South-Africa as well. These participants, being aware of their own specific societal issues, brought their own context with them. This led to debate, not of course debate about arithmetical results like that of 2 + 2, but debate about for example the acceptable level of technological complexity to be used to facilitate decision making processes: mobile phones are broadly used worldwide, but ‘virtual meeting rooms’ certainly not.

Summarising this ‘plurality of pluralities’: this last type of plurality can be called ‘contextual plurality’; the perspectival one ‘directional plurality’. Although Mouw and Griffioen [vi] dubbed the plurality of societal practices ‘associational plurality’, I prefer to use the term structural plurality in order to refer not only to the diversity of institutional constellations, associations or practices that together can be called a society, but also to the diversity disciplines that together can be called ‘science’ (taken as a formalised activity or as a body of knowledge). Both of these diversities can be explained primarily by structural features according to which reality appears to us as human beings or by the structural features according to which we human beings engage our environment. Our life conditions appear to be such that we need at least some economical behaviour and (institutionalised) economical practices, or even, so it seems, an academic discipline called economics.

One nation

In this and the next two sections I will explore which types of pluralities are relevant within the domains of the nation, the government and science. Every section I start however by supposing there are some pluralities to be found and to be defended. Given that assumption I mention a tendency that carries in itself a danger of ignoring or threatening at least one of these pluralities, putting under pressure what corresponds with this kind or these kinds of plurality in real life.

The dangerous tendency I want to explore in the domain of the nation(-state) is that of nationalism, identifiable by a series of features described by Ninian Smart. Nationalist movements are vigorous, not only in for example India or Sri Lanka (Hindu or Buddhist nationalism), but also in East- or West-European countries (Hungary, Scotland). In Hungary, for example, this nationalism is visible in the fences at the border by which refugees from Middle East of African countries are kept out.[vii] This nationalist and avertive attitude is not only triggered by ethnic differences, but by religious differences too, especially by anti-islam sentiments.

Smart, who uses a seven-dimensional model to describe religions in his introduction to The World’s Religions,[viii] adds the question: does this model also apply to ‘systems … commonly called secular: ideologies or worldviews such as scientific humanism, Marxism, Existentialism, nationalism, and so on’? [ix] As the first of three examples he selects nationalism. He describes its rituals of nationhood (e.g. the singing the national anthem), its powerful emotional side (the sentiments of patriotism), its narrative of the national history, its doctrines and principles (e.g. of self-determination and freedom), its ethical values (e.g. loyalty and a law-abiding attitude), its emphasis on the social and institutional aspects of the nation-state (e.g. the head of state), and finally the material embodiment of national pride (e.g. in great buildings and memorials). Marxism is described by Smart with a shorter but similar seven-dimensional list. More caution Smart shows mentioning features of scientific humanism, because it does not ‘embody itself in a rich way as a religious-type system’. His conclusion is nuanced:

Though to a greater or lesser extent our seven-dimensional model may apply to secular worldviews, it is not really appropriate to call them religions, or even “quasi-religions” (…). However, (…) the various systems of ideas and practices, whether religious or not, are competitors and mutual blenders, and thus can be said to play in the same league.[x]

For Smart it doesn’t matter whether someone has reasons to categorize a worldview or some -ism, for example nationalism, as secular or religious. His point is: a worldview or -ism can have observable features similar to that of religions: they ‘play in the same league’.

Now, back to nationalism itself, and the question: (how) does it put one or more types of plurality under pressure? For types of nationalism, either some nation as a (supposed) ethno-cultural entity or some nation-state as a political entity is the focus. Its unity is an essential feature of this entity – by definition, one can say. But in a more pregnant sense, emotionally, this unity has a seductive force for nationalists of most, if not all types. On the descriptive level this unity does not so much refer to geographical contours of some nation or a nation-state (the British empire consisted and still consists of several not well connected areas). However, the entity is and has to be distinguished from other nations or nation-states. It is this nation or nation-state that deserves a special role in world history. For this special role, all internal capacities and forces have to be united. So this unity of the nation(-state) is not only descriptive, but prescriptive as well: it contains a normative ideal, or better: an anti-normative ideal. This ideal, this unity has to be defended at all costs against possible intruders. Mind the absolutism here that easily gets religious overtones.

When we observe this stress on national unity, then: which types of plurality are in involved within the domain of the nation(-state)? And which types are possibly in danger? The structural plurality of diverse societal institutions or associations (postponing the diversity of disciplines within science to section 5)? The directional plurality of diverse worldviews or religions? And/or the contextual diversity, especially within the nation or nation-state?

All three of them are involved, and all of them appear to be put under pressure too – albeit in different ways, as the following examples illustrate. Let’s start with the structural (associational) plurality. Already in the Roman Empire – admittedly bigger than what is usually considered to be one nation! – collegia, brotherhoods related to some guild, mystery religions, or whatever) were raising suspicion as soon as they had some membership code that pointed to secret, members-only activities. Nowadays Russia provides an example of pressure on the freedom of media, (international) NGOs and even large companies. Putin’s party is called United Russia and in 2016 with more than 50% (!) by far (!) the biggest party of the country. The Russian Orthodox Church, like a lot of eastern orthodox churches, has strong nationalist inclinations, and is allowed to continue its public presence. Other Christian ‘flavours’ (Baptists, Pentecostal) however are having difficulties in getting along, not to mention Islamic groups. Greenpeace or Baptists are dubbed as ‘foreign’ influences. So not a secular anti-religious sentiment is threatening a directional plurality here, but nationalist feelings are threatening all kinds of ‘deviant’ societal associations.

For awareness of directional plurality, in the North-Atlantic cultural sphere immigration politics and ‘islamophobia’ is enough, too. However, not only nationalist movements (mixed with Pegida-like anti-islam sentiments) are putting this plurality under pressure. In the Netherlands part of the official integration program for immigrants consists of the presentation of ‘our’ country in a movie. Debate arose about the inclusion in this movie of topless women at the beach and of the legal marriage of a homosexual couple. A one-sided emphasis on ‘our’, modern or Western values, easily blots out the presence of allochthone critics sharing a modern worldview without supporting a libertine ethics, or of Dutch homosexual citizens that for religious reasons choose for celibacy and for communities or congregations that supports them in this choice. A supposedly majority worldview or religion endangers the (public) continuation of minority worldviews or religions.

What about the contextual plurality? Here the effects of nationalism depend on the scale of observation. Because the national context is sharper delimited from other nations or nation-states, on an international scale the contextual plurality is enhanced. But within the nation(-state) conformity can smooth out regional, tribal or other differences when defined as deviances (local folklore, ethnic traditions, etc.). A primary example is Nazi-Germany where the slogan sounded: ‘Ein Volk, Ein Reich, Ein Führer’ (one people, one empire, one leader). This type of nationalism chose (not only homosexuals and gipsies, but especially) Jews as scapegoat, erasing much of their presence in Europe. Jewish quarters in towns have lost much if not all of their Jewishness. More complicated is the Brexit-case. In reaction to ‘Brussels’, the United Kingdom as a nation-state was led into a Brexit by anti-European nationalism (among other factors). Immediately, Scottish nationalism pointed to the different voting results in their ‘nation’ (as was the case in London, too, to be honest). Internal contextual differences within a nation-state are not easily wiped out, as African and Middle-East countries like Sudan and Syria show, too.

Structural (associational), directional and contextual pluralities are all relevant, can be concluded. And, whatever the nuances, whoever is stressing the unity of a nation or nation-state, will be aware of or reminded about the existence of these pluralities, because their participants easily will fear some pressure of homogeneity.

One government

Having the types of plurality and section structure clear, the sections on government and science can be shorter. Although the unity of the government is closely related to that of a nation-state, the attention in this section will be focussed on the pluralities within a government. Although decentralising (or privatising) and centralising tendencies can occur simultaneously, I focus on the centralising tendencies. Often, a centralising tendency is related to the call for a strong leader – and someone creating or ‘listening’ to such a call…

Among the dimensions of nationalism, mentioned by Smart, the sixth one refers to the emphasis on national social institutions, for example the head of state. Of course, a government is more than a head of state. You can think of institutions like the cabinet council, government departments, parliament and senate, local governments with mayors and city councils, or, by taking the government of a country in a broad sense: political parties, public services, the police, national security service, courts and other organisations to prepare or administer laws, or to enforce ‘law and order’.

With this list, the awareness of the role of structural plurality within the government is laid bare. For this structural plurality here, ‘institutional plurality’ is a more specific term. Is this plurality put under pressure by stressing the unity of the government? And what about the other types of plurality? Starting with the former question, indeed the pressure put on the different institutions cannot be ignored. The framing of ‘the strong leader’ more often than not is followed by a degradation of the role of their party or the parliament into a mere applause machine. Power is seductive. Dictators like to give the impression of rule of law, but democratic institutions or even courts are functioning as empty shells. By reordering departments a new government (a new coalition) can show its priories. In the Netherlands a department of ‘Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries’ in 2010 has been combined with Economical Affairs and Innovation. So yes, institutional diversity, advocated already by Montesquieu to balance power, are not immune to the strong government.

The role of a parliament immediately makes clear the importance of directional plurality in a government. In a serious parliament exactly the diverse value systems of different parties, of different worldviews or even religions are providing the reason for political debate. So any tendency stressing the unity of the government at the cost of real, in depth political debate is an attack on directional plurality: it diminishes the (formal [xi]) possibilities of directional plurality that exists within society to become public and politically visible.

Finally, what about contextual plurality within the government? A typical example of the importance of contextual awareness is the decision at what government level laws have to be formulated. In some parts of the Netherlands, the so-called Bible Belt, Sunday opening hours for shops are a sensitive issue because of a majority (or at least a significant percentage) of citizens affiliated to a pietistic strand of Christianity that insist on a public Sunday rest. On the national level debates entered parliament about the stress of 24/7-consumerism, the freedom of individual consumers, and the coercive effects on shop-owners to open their shops on Sundays against their convictions or beyond their financial (employee payment) possibilities. These arguments were raised by both religious and secular parties (so religious diversity is not the only factor in this debate). In the end the decision and policymaking about opening hours of shops was referred to the local level. On the one hand this decentralisation of the decision seems to do justice to the contextual diversity within the country. On the other hand this awareness does not prevent coercive effects between neighbouring municipalities. A neoliberal free market emphasis, dominant in the central government, is influencing local contextual circumstances.

Our conclusion is that within the government of a country (government levels included) structural (institutional), directional and contextual pluralities are relevant, All three of them are under pressure when the central government, a head of state or some other of the governmental institutions becomes a position dominating the – then lost – balance of powers.

One science

Science can be considered as a worldwide methodical activity or project by humanity, aiming at the clarification of domains or aspects of our existence. The resulting, growing body of knowledge of this project can be called science, too. History of science makes clear that in a process of diversification more and more disciplines and sub-disciplines have appeared on stage, which on its turn gave rise to different types of interdisciplinarity.[xii] These types differ, among other aspects in degree of cohesion or boundary crossing that results from the cooperation between scientists from the different disciplines involved. ‘Encyclopaedic interdisciplinarity’ is just the availability of different disciplines next to each other (without any boundary crossing), ‘integrated interdisciplinary’ allows concepts and insights from one discipline to contribute to the problem-solving or theory-development of others.

When on this scale some ideal of ‘unified science’[xiii] is taken as summit of interdisciplinarity, in the work of Strijbos this unity is not taken as an ideal. His plea for interdisciplinarity is called interdisciplinarity precisely because of his conviction that irreducible pluralities exist and are to be acknowledged within the worldwide project of science or its resulting body of knowledge. So again, let’s ask whether the different types of plurality are relevant here, too, and whether an ideal of ‘unified science’ is endangering the acknowledgment of these pluralities.

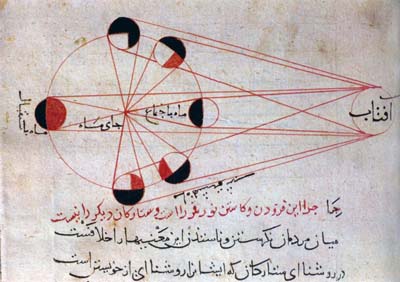

As a process leading to a structural plurality the diversification of disciplines has been mentioned already. An important point here, however, is obscured by talking about diversification. It is true that ‘philosophy’ has been a container word, encompassing for example ‘natural philosophy’ for the branches that we now call ‘natural sciences’.[xiv] This unity of ancestry suggests that a ‘unified science’ in the end is an interesting goal. However, exactly this origin and seduction does conceal the irreducibility of the diverse disciplines to each other – an anti-reductionist stance that is implied by the concept of ‘structural plurality’ here. For example, (socially) intelligent behaviour should not be reduced to (the result of) the interaction of subatomic particles. Physics is not the discipline to study psychological, social or political affairs. Types of reductionism are a permanent pressure on all sciences, apart from probably the exemplary ones: mathematics and physics.

Going over to directional plurality within science often a first reaction is that worldview or religion should have no influence on science. If it would not have been an example of is/ought-reasoning, someone could easily add: worldview or religion has no influence whatsoever on mathematics (2+2=4) or physics (a quark behaves as a quark). True enough. However, in real life the development of science takes place in a cultural and political environment in which worldview and religion does play a role. And that is not only a matter of external context, it is part of the mind-set of the scientists themselves, not to mention the managers of universities. Choices about research direction are made by groups of people with their specific interests, problem priorities, value systems and other personal or institutional resources. The claim that science is able to have an autonomous development, ruled by scientific reasoning only, will be difficult to substantiate. The reality is: there are scientists adhering worldviews or religions that fuel a value system in which science should serve urgent societal problems.[xv] Should the work of these last type scientists be excluded from the worldwide project of humanity called ‘science’?

The reality is, too, that not only the choices of research direction, but also the subsequent work is laden with personal views and convictions: what about the interpretative and normative questions that especially in the humanities are part and parcel of the work? Either you are a behaviourist, or not. Are human beings ‘nothing but’ an emergent phaenomenon ‘ultimately’ based on matter and energy, or is there some ontological irreducibility that explains the epistemic irreducibility mentioned before? So here: directional plurality will be visible in the real life development of sciences. Some ideal of ‘unified science’ can lead to nervousness about the existence of parallel paradigms in research development or to devaluate research directions that do not sit easily with one’s convictions (whether reductionist or not, for example).

Turning to contextual plurality, the context in which scientists live and work and make their decisions is mentioned just before. Nobody can deny the different circumstances in which scientists worldwide are doing their work. This does influence the development of their research. In Cameroon, scientists can have an interest in the Benoué valley in the North.[xvi] I guess that it will be difficult in most African countries to develop frontier knowledge in the field of nanotechnology or nuclear physics. In dealing with scientific contributions from all over the world, scientists usually will be aware of these kinds of contextual differences. However, here I don’t see compelling reasons to think that some ideal of ‘unified science’ would be disturbed by the contextual differences within our global village. Academic standards usually are guarded by international journals and accreditation organisations.

Within science, we can conclude, all three types of plurality again are relevant. However, under pressure by some ideal of ‘unified science’ are only two of these three types: the acknowledgment of structural plurality of irreducible disciplines, and the acknowledgment of directional plurality because of worldviewish and religious influences. The contextual plurality itself will be too unavoidable not to be acknowledged (see the just mentioned Cameroon example). Potential pressure on the structural plurality of sciences becomes clear when observing non-natural sciences (e.g. sociology, cultural anthropology) having to defend their methodologically ‘weaker’ approaches in comparison to the ‘exact’ sciences. Potential pressure on the directional plurality of sciences becomes clear when observing that for example within the economic sciences some paradigms or schools (e.g. the Chicago school of economics) can gain (and have gained) prominence at the cost of other approaches.

What do we gain, acknowledging this plurality of pluralities?

6.1 In a pluralistic world

In what ways can citizens, politicians or scientists profit from the foregoing discussion of types of plurality? By distinguishing types of plurality and by giving a range of quite diverse examples, I have shown the relevance of these pluralities within nation-states, governments and sciences. Ignoring them will lead to social unrest or more serious disharmony among groups of citizens, among sensitive politicians or among groups of scientists. So, paradoxically, the acknowledgement by politicians or scientists of both a plurality of pluralities and of the existence of those pluralities in the reality of real life and real science, will promote a kind of unity among people that can be called harmony, a multicultural harmony, if you want. By acknowledging the pluralistic complexities of the real world, politicians and scientist do more justice to people in their real circumstances.

Talking about a plurality of pluralities is not just word play. In political terms, it is a matter of justice, in the end: a matter of doing justice to human beings in their diverse associations (e.g. schools), with their diverse beliefs and values, in their diverse contexts. The complexity of reality asks for complex social or epistemological philosophies, refined enough to do justice to complexities of real life or real science. Disclosive Systems Thinking is a type of systems thinking that has been informed by traditions of complex philosophy, among which the ‘Amsterdam School’ founded by Herman Dooyeweerd (1894-1977) has been a prominent source.[xvii] Only a real understanding of complex reality can lead to mutual understanding of human beings and to relevant development of their practices.

In the assessment of evidence-based politics

This essay started with the question: Is evidence-based politics an idea a monolithic view of society? In the first place, by exploring different types of plurality any monolithic view of society itself is made object of debate. Whether or not society is considered to be an association of associations, it is not one social body or one political pyramid at the top of which one government can act as a Pharaoh considering all that is below him to be his possession. Maybe, within a society some worldview or religion is a dominating, a worldview or religion considered by a majority of the citizens to be a trustworthy and reasonable guide for a serious or even meaningful way of life. But nobody should force any of these citizens to forget his or her own worldview or religion when interpretative or normative views are involved in politics or scientific work. Maybe, contextual differences in regions, tribes or social strata of a (global) society are not that big that people don’t understand each other anymore. Even then, people should be aware of the contextual differences that do play a role in the (scientific) ideas and ways of life that they develop.

Secondly, an evidence-based approach of politics is inclined to ignore the different types of plurality that have been presented. There are structural differences between sciences, some being more quantitative, others being more qualitative – just to mention one important difference. Is an evidence-based approach in practical reality not having a bias towards those sciences in which quantitative or specifically statistical methods play an important role? Furthermore, isn’t evidence-based politics inclined to legitimize policy proposals with an appeal to (some) sciences, ignoring directional differences and debates that nevertheless are important in real life? Examples here are (Dutch) debates about vaccination (e.g. against polio). Several groups in society opposed vaccination at all (e.g. anthroposophical groups, strict Calvinist groups). Statistics about the positive results of vaccination do not take into account the real convictions behind this opposition. Debates in parliament can make these differences explicit. Finally, evidence based politics fails to do justice to contextual differences. Political priorities are not only a matter of numbers, but are related to societal situations and the personal convictions and circumstances of groups within this society. A debate about ritual slaughter of animals is no only a matter of pain indicators, but a matter of religious or freedom as well.

This critique of the reductionist effects of an evidence-based approach to politics echoes the critique voiced in report about ‘Evidence-Based Practice’ (EBP) in health care, published June 2017 in the Netherlands by the Council for Public Health and Society. Although the authors acknowledge the value of systematic reflection on the consequences and results of medical interventions, they signal the limits of this EBP-approach, too. In their main criticism the authors refer to the role of the context and the context-related issue what good care is within this specific context. This is easily ignored by an EBP-approach: ‘What exactly is the good to be done – that can differ for every single client and his or her situation. Furthermore, changes occur in what is considered to be good care.’[xviii] In these two remarks we see a defence to acknowledge both contextual and directional pluralities. A second criticism is directed towards the risk of an EBP-approach to argue mainly on the basis of quantitative (statistical) experiments. This criticism is a defence of the structural plurality that a diversity types of academic or practical reasoning can be relevant in the specific health care situations. Omitted here is a third criticism which targets the authoritative status of quality standards formulated using an EBP-approach: this easily leads to unwarranted standardization.

Governments are – at least indirectly – responsible for the nation-wide public health care, its quality standards and its funding. Given the fact that the EBP-approach can be criticized along lines as mentioned here, governments themselves should be careful in their appeal to evidence-based policies in the domain of health care. More generally, governments should be aware that evidence-based policy making is evoking similar criticism as worded about the EBP-approach within health care. Politics is related to specific contexts (the nation as a whole, and/or their differing local areas), to debate about different values hierarchies (of liberals, social-democrats, conservatives, Christians, humanists, etc.), and to structurally different styles of theoretical and practical reasoning and other types of communicative exchange.In conclusion: in this essay three secular seductions have been explored: the seductions to be one strong-and-special nation (with a special ‘calling’ in world history…), to have one strong government, and to strife for one all-encompassing science. At least three different types of plurality are presented to make clear that things probably are a Bit More Complicated Than That. Disclosive Systems Thinking can be interpreted as an approach to social studies that tries to do justice to this complexity of the real world that politicians, citizens and scientists all live in.

Notes

[i] See e.g. http://www.lse.ac.uk/government/research/resgroups/CPPAR/Documents/Evidence-based-politics-Government-and-the-production-of-policy-research.pdf. Accessed 13-10-2017.

[ii] In the section ‘Evidence-Based Policy’ of his book I Think You’ll Find It’s a Bit More Complicated Than That (London: Fourth Estate, 2014), 169-218, psychiatrist and science writer Ben Goldacre gives a dozen (often funny) examples of insufficient or misguiding use of evidence, by politicians too. I myself have no statistical evidence whether ‘evidence-based politics’ is a hype that has reached its peak already or will reach that peak soon, or that this approach will be a more permanent legitimation style in politics. I assume the latter.

[iii] The relation between ‘this’ and the ‘other’ world is more complicated than these terms suggest, even to the point that the terms themselves are misleading. See works by theologians who emphasize the ‘immanence’ of God, e.g. John Milbank (2006).

[iv] Sytse Strijbos, ‘Towards a New Interdisciplinarity’, in Rob A. Nijhoff, Jan van der Stoep, Sytse Strijbos (eds.) Towards a New Interdisciplinarity. Proceedings of the 9th Annual Working Conference of CPTS (Maarssen: CPTS, 2003), 133-138; here: 137.

[v] Gerald Midgley, ‘Reflections on the CPTS Model of Interdisciplinarity’, in: Sytse Strijbos, Andrew Basden (eds.), In Search of an Integrative Vision for Technology. Interdisciplinary Studies in Information Systems (New York NY: Springer 2006), 259-268; here: 267.

[vi] I am following here the analysis in Mouw, Richard, and Griffioen, Sander. Pluralisms and Horizons: An Essay in Christian Public Philosophy (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1993), summarised: on pp.168-173. Mouw and Griffioen share with Strijbos awareness of the philosophical legacy of the Dutch philosopher Herman Dooyeweerd (see note 11).

[vii] Migrant crisis: Hungary declares emergency at Serbia border. BBC News. 15 September 2015; see http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-34252812 (accessed June2, 2017).

[viii] Ninian Smart, The World’s Religions. Second Edition (Cambridge: CUP, 21998), 13-22. The seven dimensions are italicised in the description of nationalism (immediately following).

[ix] Ninian Smart, The World’s Religions, 22. The example of nationalism follows immediately (22-25).

[x] Smart, The World’s Religions, 26.

[xi] This critique is touching the work of Jürgen Habermas as well. Although Habermas certainly opposes any oppressive government and (especially since 2001) explicitly invites religious traditions to join in in public debate. He is too afraid for religious views to allow them to be voiced by people having formal political function during their professional activities – even members of parliament! See the recurrent debates of this restriction in Craig Calhoun et al. (eds.), Habermas and Religion (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2013).

[xii] Sytse Strijbos, Andrew Basden, ‘Introduction: In Search for an Integrative Vision for Technology’, in: Sytse Strijbos, Andrew Basden (eds.), In Search of an Integrative Vision for Technology. Interdisciplinary Studies in Information Systems (New York: Springer, 2006), 1-16; here: 1-2, with reference to M.A. Boden ‘What is interdisciplinarity?’, in: R. Cunningham (ed.) Interdisciplinarity and the Organisation of Knowledge in Europe (Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 1999), 13-24.

[xiii] Otto Neurath (1882-1945) is one of the names related to such an ideal. For an overview of at least 15 types of scientism: see Rik Peels, ‘A Conceptual Map of Scientism’, in: Jeroen de Ridder, Rik Peels, and René van Woudenberg (eds.), Scientism: Prospects and Problems (New York: Oxford University Press, forthcoming). Peels categorizes the type of scientism that Neurath advocates as one of the ‘eliminative’ types of scientism, within the spectrum of ‘academic’ types of scientism that Peels distinguishes.

[xiv] Cf. the title of Isaac Newton, Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (London: Royal Society, 1687).

[xv] See e.g. Nathan D. Shannon, Shalom and the Ethics of Belief. Nicholas Wolterstorff’s Theory of Situated Rationality (Eugene OR: Pickwick Publications, 2015).

[xvi] This is a real life example: this year, Gustave Gaye defended a PhD-thesis on this region (2016) at the Cameroon Institut Universitaire de Développement International (see http://www.iudi.org).

[xvii] See Jonathan Chaplin, Herman Dooyeweerd. Christian Philosopher of State and Civil Society (Notre Dame IN: UNDP, 2011). Chaplin’s writing style is more precise and readable than Dooyeweerd’s.

[xviii] ‘Wat het goede is om te doen kan per patiënt en per situatie verschillen. Opvattingen over wat goede zorg is zijn bovendien aan verandering onderhevig.’ (RVS 2017:9).

References

Craig Calhoun et al. (eds.), Habermas and Religion (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2013)

Jonathan Chaplin, Herman Dooyeweerd. Christian Philosopher of State and Civil Society (Notre Dame IN: UNDP, 2011)

Ben Goldacre, I Think You’ll Find It’s a Bit More Complicated Than That (London: Fourth Estate, 2014)

Gerald Midgley, ‘Reflections on the CPTS Model of Interdisciplinarity’, in: Sytse Strijbos, Andrew Basden (eds.), In Search of an Integrative Vision for Technology. Interdisciplinary Studies in Information Systems (New York: Springer, 2006), 259-268

John Milbank, Theology and social theory: Beyond secular reason (Oxford etc.: Blackwell, 22006)

Rik Peels, ‘A Conceptual Map of Scientism’, in: Jeroen de Ridder, Rik Peels, and René van Woudenberg (eds.), Scientism: Problems and Prospects (New York: Oxford University Press, forthcoming)

Raad voor Volksgezondheid en Samenleving [RVS], Zonder context geen bewijs. Over de illusie van evidence-based practice in de zorg [Without context no evidence. On the illusion of evidence-based practice in health care] (Den Haag: RVS, 2017)

Nathan D. Shannon, Shalom and the Ethics of Belief. Nicholas Wolterstorff’s Theory of Situated Rationality (Eugene OR: Pickwick, 2015)

Ninian Smart, The World’s Religions. Second Edition (Cambridge: CUP, 21998)

Sytse Strijbos, ‘Towards a new interdisciplinarity’, in: Rob A. Nijhoff, Jan van der Stoep, Sytse Strijbos (eds.) Towards a New Interdisciplinarity. Proceedings of the 9th Annual Working Conference of CPTS (Maarssen: CPTS, 2003),

Sytse Strijbos, Andrew Basden (eds.), In Search of an Integrative Vision for Technology. Interdisciplinary Studies in Information Systems (New York NY: Springer, 2006)

Sytse Strijbos, Andrew Basden, ‘Introduction: In Search for an Integrative Vision for Technology’, in: Sytse Strijbos, Andrew Basden (eds.), In Search of an Integrative Vision for Technology. Interdisciplinary Studies in Information Systems (New York: Springer, 2006), 1-16

Charles Taylor, A Secular Age (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2007)

Online resources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Types_of_nationalism

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_Russia

http://www.iudi.org

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/nationalism

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/patriotism

http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-34252812

http://www.lse.ac.uk/government/research/resgroups/CPPAR/Documents/Evidence-based-politics-Government-and-the-production-of-policy-research.pdf

https://www.raadrvs.nl/publicaties/item/zonder-context-geen-bewijs